- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction & Top Questions

Formative influences

Influence of the scientific revolution, work during the plague years.

- Inaugural lectures at Trinity

- Controversy

- Influence of the Hermetic tradition

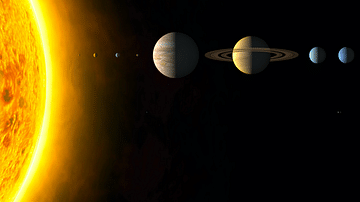

- Planetary motion

- Universal gravitation

- Warden of the mint

- Interest in religion and theology

- Leader of English science

- Final years

What is Isaac Newton most famous for?

How was isaac newton educated, what was isaac newton’s childhood like.

- What is the Scientific Revolution?

- How is the Scientific Revolution connected to the Enlightenment?

Isaac Newton

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Isaac Newton Institute of Mathematical Sciences - Who was Isaac Newton?

- Science Kids - Fun Science and Technology for Kids - Biography of Isaac Newton

- Trinity College Dublin - School of mathematics - Biography of Sir Isaac Newton

- World History Encyclopedia - Isaac Newton

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy - Biography of Isaac Newton

- University of British Columbia - Physics and Astronomy Department - The Life and Work of Newton

- LiveScience - Biography of Isaac Newton

- Physics LibreTexts - Newton's Laws of Motion

- Isaac Newton - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- Isaac Newton - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

Although Isaac Newton is well known for his discoveries in optics (white light composition) and mathematics ( calculus ), it is his formulation of the three laws of motion —the basic principles of modern physics—for which he is most famous. His formulation of the laws of motion resulted in the law of universal gravitation .

After interrupted attendance at the grammar school in Grantham, Lincolnshire , England , Isaac Newton finally settled down to prepare for university, going on to Trinity College, Cambridge , in 1661, somewhat older than his classmates. There he immersed himself in Aristotle ’s work and discovered the works of René Descartes before graduating in 1665 with a bachelor’s degree.

Isaac Newton was born to a widowed mother (his father died three months prior) and was not expected to survive, being tiny and weak. Shortly thereafter Newton was sent by his stepfather, the well-to-do minister Barnabas Smith, to live with his grandmother and was separated from his mother until Smith’s death in 1653.

What did Isaac Newton write?

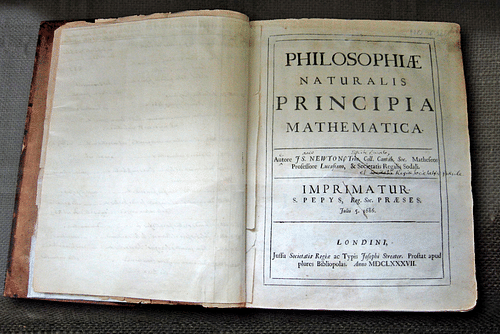

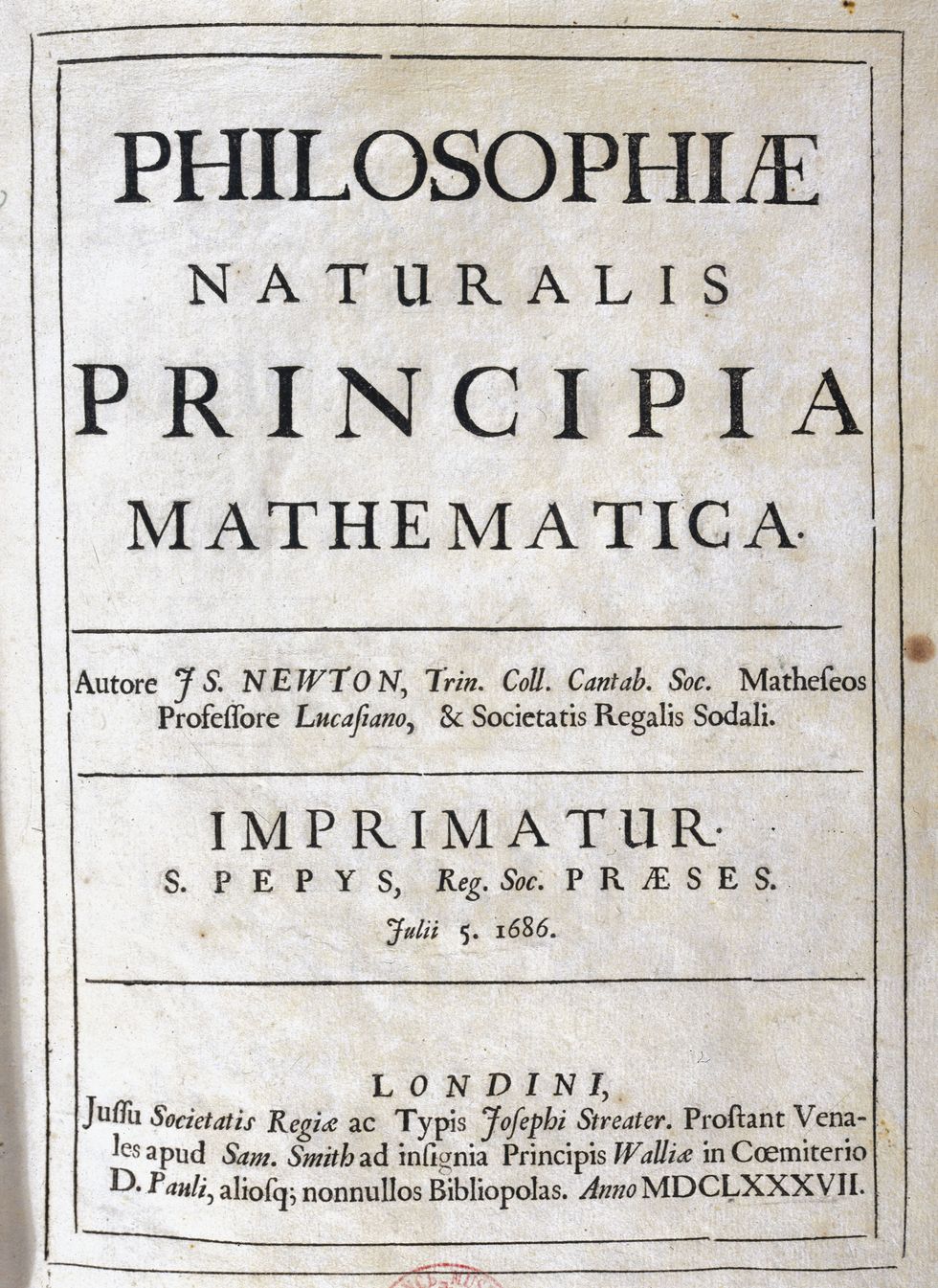

Isaac Newton is widely known for his published work Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica (1687), commonly known as the Principia . His laws of motion first appeared in this work. It is one of the most important single works in the history of modern science .

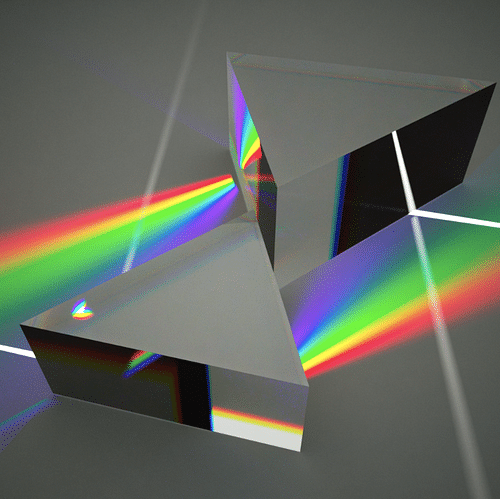

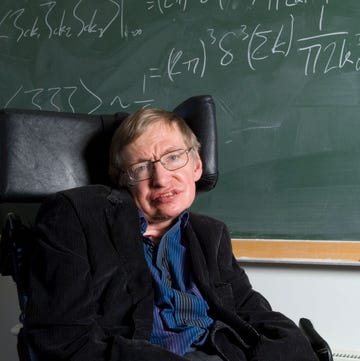

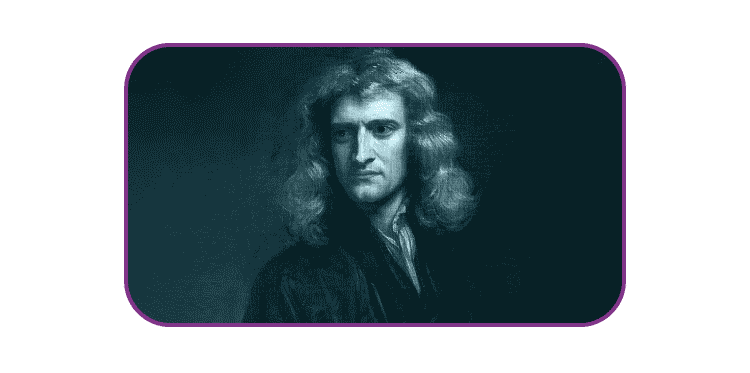

Isaac Newton (born December 25, 1642 [January 4, 1643, New Style], Woolsthorpe, Lincolnshire , England—died March 20 [March 31], 1727, London) was an English physicist and mathematician who was the culminating figure of the Scientific Revolution of the 17th century. In optics , his discovery of the composition of white light integrated the phenomena of colours into the science of light and laid the foundation for modern physical optics. In mechanics , his three laws of motion , the basic principles of modern physics , resulted in the formulation of the law of universal gravitation . In mathematics , he was the original discoverer of the infinitesimal calculus . Newton’s Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica ( Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy , 1687) was one of the most important single works in the history of modern science.

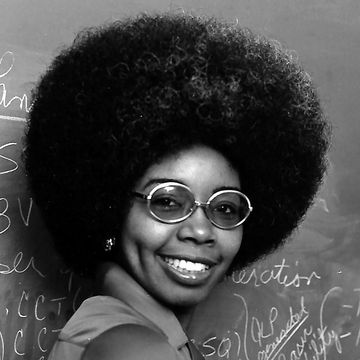

Born in the hamlet of Woolsthorpe, Newton was the only son of a local yeoman , also Isaac Newton, who had died three months before, and of Hannah Ayscough. That same year, at Arcetri near Florence, Galileo Galilei had died; Newton would eventually pick up his idea of a mathematical science of motion and bring his work to full fruition . A tiny and weak baby, Newton was not expected to survive his first day of life, much less 84 years. Deprived of a father before birth, he soon lost his mother as well, for within two years she married a second time; her husband, the well-to-do minister Barnabas Smith, left young Isaac with his grandmother and moved to a neighbouring village to raise a son and two daughters. For nine years, until the death of Barnabas Smith in 1653, Isaac was effectively separated from his mother, and his pronounced psychotic tendencies have been ascribed to this traumatic event. That he hated his stepfather we may be sure. When he examined the state of his soul in 1662 and compiled a catalog of sins in shorthand, he remembered “Threatning my father and mother Smith to burne them and the house over them.” The acute sense of insecurity that rendered him obsessively anxious when his work was published and irrationally violent when he defended it accompanied Newton throughout his life and can plausibly be traced to his early years.

After his mother was widowed a second time, she determined that her first-born son should manage her now considerable property. It quickly became apparent, however, that this would be a disaster, both for the estate and for Newton. He could not bring himself to concentrate on rural affairs—set to watch the cattle, he would curl up under a tree with a book. Fortunately, the mistake was recognized, and Newton was sent back to the grammar school in Grantham , where he had already studied, to prepare for the university. As with many of the leading scientists of the age, he left behind in Grantham anecdotes about his mechanical ability and his skill in building models of machines, such as clocks and windmills . At the school he apparently gained a firm command of Latin but probably received no more than a smattering of arithmetic. By June 1661 he was ready to matriculate at Trinity College , Cambridge , somewhat older than the other undergraduates because of his interrupted education.

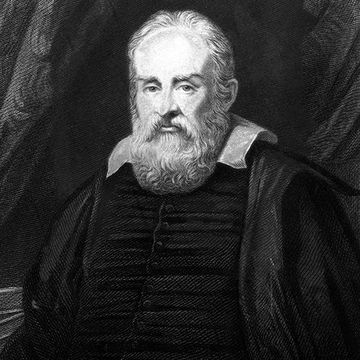

When Newton arrived in Cambridge in 1661, the movement now known as the Scientific Revolution was well advanced, and many of the works basic to modern science had appeared. Astronomers from Nicolaus Copernicus to Johannes Kepler had elaborated the heliocentric system of the universe . Galileo had proposed the foundations of a new mechanics built on the principle of inertia . Led by René Descartes , philosophers had begun to formulate a new conception of nature as an intricate, impersonal, and inert machine. Yet as far as the universities of Europe, including Cambridge, were concerned, all this might well have never happened. They continued to be the strongholds of outmoded Aristotelianism , which rested on a geocentric view of the universe and dealt with nature in qualitative rather than quantitative terms.

Like thousands of other undergraduates, Newton began his higher education by immersing himself in Aristotle’s work. Even though the new philosophy was not in the curriculum, it was in the air. Some time during his undergraduate career, Newton discovered the works of the French natural philosopher Descartes and the other mechanical philosophers, who, in contrast to Aristotle, viewed physical reality as composed entirely of particles of matter in motion and who held that all the phenomena of nature result from their mechanical interaction. A new set of notes, which he entitled “ Quaestiones Quaedam Philosophicae ” (“Certain Philosophical Questions”), begun sometime in 1664, usurped the unused pages of a notebook intended for traditional scholastic exercises; under the title he entered the slogan “Amicus Plato amicus Aristoteles magis amica veritas” (“Plato is my friend, Aristotle is my friend, but my best friend is truth”). Newton’s scientific career had begun.

The “Quaestiones” reveal that Newton had discovered the new conception of nature that provided the framework of the Scientific Revolution. He had thoroughly mastered the works of Descartes and had also discovered that the French philosopher Pierre Gassendi had revived atomism , an alternative mechanical system to explain nature. The “Quaestiones” also reveal that Newton already was inclined to find the latter a more attractive philosophy than Cartesian natural philosophy, which rejected the existence of ultimate indivisible particles. The works of the 17th-century chemist Robert Boyle provided the foundation for Newton’s considerable work in chemistry. Significantly, he had read Henry More , the Cambridge Platonist, and was thereby introduced to another intellectual world, the magical Hermetic tradition, which sought to explain natural phenomena in terms of alchemical and magical concepts. The two traditions of natural philosophy, the mechanical and the Hermetic, antithetical though they appear, continued to influence his thought and in their tension supplied the fundamental theme of his scientific career.

Although he did not record it in the “Quaestiones,” Newton had also begun his mathematical studies. He again started with Descartes, from whose La Géometrie he branched out into the other literature of modern analysis with its application of algebraic techniques to problems of geometry . He then reached back for the support of classical geometry. Within little more than a year, he had mastered the literature; and, pursuing his own line of analysis, he began to move into new territory. He discovered the binomial theorem , and he developed the calculus , a more powerful form of analysis that employs infinitesimal considerations in finding the slopes of curves and areas under curves.

By 1669 Newton was ready to write a tract summarizing his progress, De Analysi per Aequationes Numeri Terminorum Infinitas (“On Analysis by Infinite Series”), which circulated in manuscript through a limited circle and made his name known. During the next two years he revised it as De methodis serierum et fluxionum (“ On the Methods of Series and Fluxions ”). The word fluxions , Newton’s private rubric, indicates that the calculus had been born. Despite the fact that only a handful of savants were even aware of Newton’s existence, he had arrived at the point where he had become the leading mathematician in Europe.

When Newton received the bachelor’s degree in April 1665, the most remarkable undergraduate career in the history of university education had passed unrecognized. On his own, without formal guidance, he had sought out the new philosophy and the new mathematics and made them his own, but he had confined the progress of his studies to his notebooks. Then, in 1665, the plague closed the university, and for most of the following two years he was forced to stay at his home, contemplating at leisure what he had learned. During the plague years Newton laid the foundations of the calculus and extended an earlier insight into an essay, “Of Colours,” which contains most of the ideas elaborated in his Opticks . It was during this time that he examined the elements of circular motion and, applying his analysis to the Moon and the planets , derived the inverse square relation that the radially directed force acting on a planet decreases with the square of its distance from the Sun —which was later crucial to the law of universal gravitation. The world heard nothing of these discoveries.

45,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. Take the first step today

Meet top uk universities from the comfort of your home, here’s your new year gift, one app for all your, study abroad needs, start your journey, track your progress, grow with the community and so much more.

Verification Code

An OTP has been sent to your registered mobile no. Please verify

Thanks for your comment !

Our team will review it before it's shown to our readers.

- School Education /

Essay on Isaac Newton: The Father of Modern Science

- Updated on

- Mar 15, 2024

Did you know Isaac Newton almost gave up on his education before discovering the laws of motion? Born in 1642, Isaac Newton was an English mathematician , physicist , astronomer, and author who is widely recognized as one of the most influential scientists in history. He is known as the father of modern physics. He made significant contributions to various fields of science and mathematics, and his work laid the foundation for many scientific principles and discoveries. Let’s find out more about Isaac Newton with the essays written below.

Table of Contents

- 1 Things to keep in Mind while Writing Essay on Isaac Newton

- 2 Essay on Isaac Newton in 100 Words

- 3 Essay on Isaac Newton in 200 Words

- 4 Essay on Isaac Newton in 300 Words

Also Read – Essay on Chandrayaan-3

Things to keep in Mind while Writing Essay on Isaac Newton

- Isaac Newton was born on 4th January 1643.

- He is famous for discovering the phenomenon of white light integrated with colours which further presented as the foundation of modern physical optics.

- He is known for formulating the three laws of motion and the laws of gravitation which changed the track of physics all across the globe.

- In mathematics, he is known as the originator of calculus.

- He was knighted in 1705 hence, he came to be known as “Sir Isaac Newton”.

Essay on Isaac Newton in 100 Words

Issac Newton was an English scientist who made some groundbreaking discoveries in the field of science and revolutionized physics and mathematics. revolutionized physics and mathematics. He formulated the three laws of motion , defining how objects move and interact with forces. His law of universal gravitation explained planetary motion. Newton independently developed calculus, a fundamental branch of mathematics.

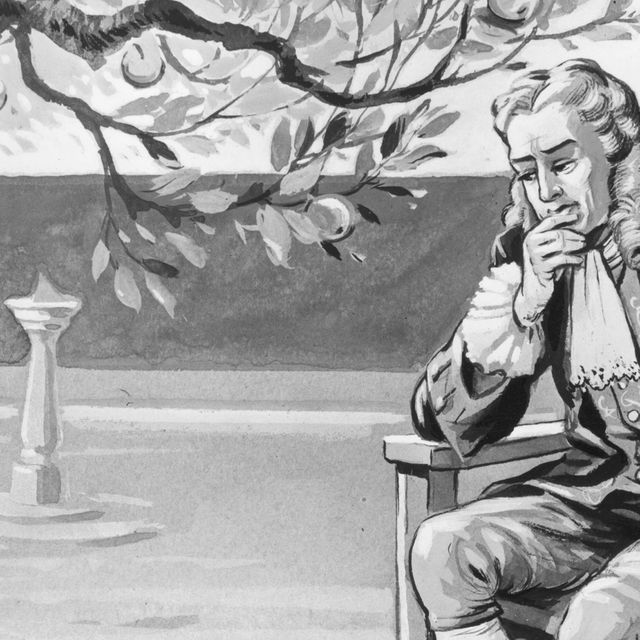

Everybody knows Newton because of the apply story, in which he was sitting under a tree when an apple fell on him. His ‘Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica’ remains a cornerstone of scientific thought. Newton’s profound insights continue to shape our understanding of the natural world.

Also Read – Essay on Technology

Essay on Isaac Newton in 200 Words

Born in 1642, Isaac Newton is one of the most influential scientists of all time. His groundbreaking contributions in physics, astronomy and mathematics helped reshape the understanding of the natural world. Our science books mention Newton’s three laws of motion which brought a revolution in physics.

- Newton’s first law of motion, also known as the law of inertia, states that an object will stay at rest unless acted upon by an outside force.

- The second law of motion states that an object’s acceleration is produced by a net force that is directly proportional to the net force’s magnitude.

- The third law of motion states that every action has an equal and opposite reaction.

All these laws laid the foundation for classical mechanics, revolutionizing the way we comprehend the physical world. He is known as the father of modern physics.

In mathematics, Newton developed calculus independently. His work in calculus was essential for solving complex mathematical problems, making it a cornerstone of modern mathematics and science.

His work ‘Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica’ was published in 1687, and remains a monumental work that underpins modern science. His profound insights continue to shape our understanding of the universe, making Isaac Newton one of history’s most influential and celebrated scientists.

Essay on Isaac Newton in 300 Words

Isaac Newton was an English scientist who was known for his groundbreaking discoveries in the fields of Physics, Mathematics and Astronomy. Thanks to his discoveries of revolutionizing our understanding of the natural world.

One of his well-known discoveries was the three laws of motion, also known as Newton’s three laws of motion.

- The first law, known as the law of inertia, states that objects at rest tend to stay at rest, and objects in motion tend to stay in motion unless acted upon by an external force.

- The second law quantifies how forces affect an object’s motion, introducing the famous equation F = ma (force equals mass times acceleration).

- The third law, the law of action and reaction, explains that for every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction.

These laws provided a comprehensive framework for understanding and predicting the behaviour of physical objects, from the motion of planets to the fall of an apple.

Another groundbreaking achievement of Newton was the discovery of the universal law of gravitation. This law states that every object in the universe attracts every other object with a force directly proportional to their masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them.

It explained the mechanics of planetary motion and demonstrated that the same laws that govern objects on Earth also apply to celestial bodies, unifying the terrestrial and celestial realms.

In mathematics, Newton independently developed a powerful mathematical tool, called calculus, for analyzing rates of change and solving complex problems. His work laid the groundwork for modern calculus and transformed mathematics, physics, and engineering.

Newton’s magnum opus, “Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica” (Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy), published in 1687, is a landmark work that brought together his laws of motion and the law of universal gravitation.

Related Articles:

- Essay on Rabindranath Tagore

- Essay on Allama Iqbal

- Essay on Technology

- Essay on Mahatma Gandhi

Issac Newton was an English mathematician, astronomer, theologian, alchemist, author and physicist, was known for the discovery of the laws of gravity, and worked on the principles of visible light and the laws of motion.

Newton’s three laws of motion are: first law of motion (law of inertia), which states that an object will stay at rest unless acted upon by an outside force; The second law of motion states that an object’s acceleration is produced by a net force that is directly proportional to the net force’s magnitude; The third law of motion states that every action has an equal and opposite reaction.

Issac Newton is known as the father of modern physics and was associated with Cambridge University as a physicist and mathematician.

For more information on such interesting topics, visit our essay writing page and make sure to follow Leverage Edu .

Shiva Tyagi

With an experience of over a year, I've developed a passion for writing blogs on wide range of topics. I am mostly inspired from topics related to social and environmental fields, where you come up with a positive outcome.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Contact no. *

Connect With Us

45,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. take the first step today..

Resend OTP in

Need help with?

Study abroad.

UK, Canada, US & More

IELTS, GRE, GMAT & More

Scholarship, Loans & Forex

Country Preference

New Zealand

Which English test are you planning to take?

Which academic test are you planning to take.

Not Sure yet

When are you planning to take the exam?

Already booked my exam slot

Within 2 Months

Want to learn about the test

Which Degree do you wish to pursue?

When do you want to start studying abroad.

January 2024

September 2024

What is your budget to study abroad?

How would you describe this article ?

Please rate this article

We would like to hear more.

Have something on your mind?

Make your study abroad dream a reality in January 2022 with

India's Biggest Virtual University Fair

Essex Direct Admission Day

Why attend .

Don't Miss Out

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Isaac Newton

By: History.com Editors

Updated: October 16, 2023 | Original: March 10, 2015

![essay on isaac newton biography Sir Isaac NewtonENGLAND - JANUARY 01: Sir Isaac Newton (1642-1727) .Canvas. (Photo by Imagno/Getty Images) [Sir Isaac Newton (1642-1727) . Gemaelde.]](https://assets.editorial.aetnd.com/uploads/2015/03/isaac-newton-gettyimages-56458980.jpg?width=3840&height=1920&crop=3840%3A1920%2Csmart&quality=75&auto=webp)

Isaac Newton is best know for his theory about the law of gravity, but his “Principia Mathematica” (1686) with its three laws of motion greatly influenced the Enlightenment in Europe. Born in 1643 in Woolsthorpe, England, Sir Isaac Newton began developing his theories on light, calculus and celestial mechanics while on break from Cambridge University.

Years of research culminated with the 1687 publication of “Principia,” a landmark work that established the universal laws of motion and gravity. Newton’s second major book, “Opticks,” detailed his experiments to determine the properties of light. Also a student of Biblical history and alchemy, the famed scientist served as president of the Royal Society of London and master of England’s Royal Mint until his death in 1727.

Isaac Newton: Early Life and Education

Isaac Newton was born on January 4, 1643, in Woolsthorpe, Lincolnshire, England. The son of a farmer who died three months before he was born, Newton spent most of his early years with his maternal grandmother after his mother remarried. His education was interrupted by a failed attempt to turn him into a farmer, and he attended the King’s School in Grantham before enrolling at the University of Cambridge’s Trinity College in 1661.

Newton studied a classical curriculum at Cambridge, but he became fascinated by the works of modern philosophers such as René Descartes, even devoting a set of notes to his outside readings he titled “Quaestiones Quaedam Philosophicae” (“Certain Philosophical Questions”). When the Great Plague shuttered Cambridge in 1665, Newton returned home and began formulating his theories on calculus, light and color, his farm the setting for the supposed falling apple that inspired his work on gravity.

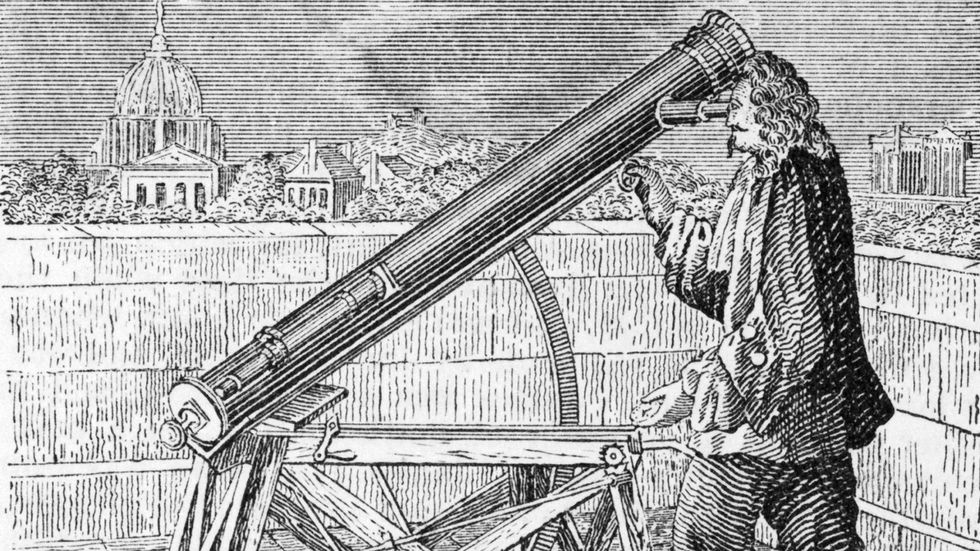

Isaac Newton’s Telescope and Studies on Light

Newton returned to Cambridge in 1667 and was elected a minor fellow. He constructed the first reflecting telescope in 1668, and the following year he received his Master of Arts degree and took over as Cambridge’s Lucasian Professor of Mathematics. Asked to give a demonstration of his telescope to the Royal Society of London in 1671, he was elected to the Royal Society the following year and published his notes on optics for his peers.

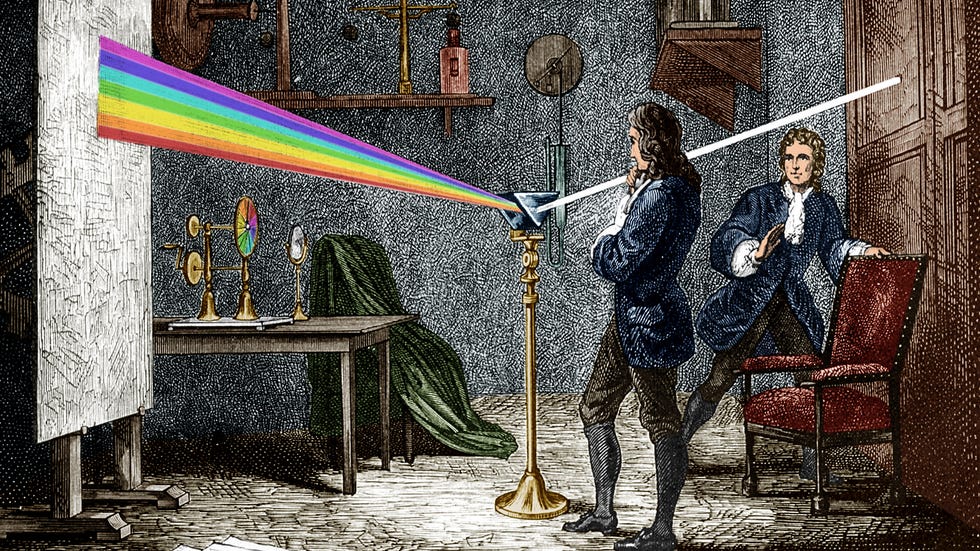

Through his experiments with refraction, Newton determined that white light was a composite of all the colors on the spectrum, and he asserted that light was composed of particles instead of waves. His methods drew sharp rebuke from established Society member Robert Hooke, who was unsparing again with Newton’s follow-up paper in 1675.

Known for his temperamental defense of his work, Newton engaged in heated correspondence with Hooke before suffering a nervous breakdown and withdrawing from the public eye in 1678. In the following years, he returned to his earlier studies on the forces governing gravity and dabbled in alchemy.

Isaac Newton and the Law of Gravity

In 1684, English astronomer Edmund Halley paid a visit to the secluded Newton. Upon learning that Newton had mathematically worked out the elliptical paths of celestial bodies, Halley urged him to organize his notes.

The result was the 1687 publication of “Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica” (Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy), which established the three laws of motion and the law of universal gravity. Newton’s three laws of motion state that (1) Every object in a state of uniform motion will remain in that state of motion unless an external force acts on it; (2) Force equals mass times acceleration: F=MA and (3) For every action there is an equal and opposite reaction.

“Principia” propelled Newton to stardom in intellectual circles, eventually earning universal acclaim as one of the most important works of modern science. His work was a foundational part of the European Enlightenment .

With his newfound influence, Newton opposed the attempts of King James II to reinstitute Catholic teachings at English Universities. King James II was replaced by his protestant daughter Mary and her husband William of Orange as part of the Glorious Revolution of 1688, and Newton was elected to represent Cambridge in Parliament in 1689.

Newton moved to London permanently after being named warden of the Royal Mint in 1696, earning a promotion to master of the Mint three years later. Determined to prove his position wasn’t merely symbolic, Newton moved the pound sterling from the silver to the gold standard and sought to punish counterfeiters.

The death of Hooke in 1703 allowed Newton to take over as president of the Royal Society, and the following year he published his second major work, “Opticks.” Composed largely from his earlier notes on the subject, the book detailed Newton’s painstaking experiments with refraction and the color spectrum, closing with his ruminations on such matters as energy and electricity. In 1705, he was knighted by Queen Anne of England.

Isaac Newton: Founder of Calculus?

Around this time, the debate over Newton’s claims to originating the field of calculus exploded into a nasty dispute. Newton had developed his concept of “fluxions” (differentials) in the mid 1660s to account for celestial orbits, though there was no public record of his work.

In the meantime, German mathematician Gottfried Leibniz formulated his own mathematical theories and published them in 1684. As president of the Royal Society, Newton oversaw an investigation that ruled his work to be the founding basis of the field, but the debate continued even after Leibniz’s death in 1716. Researchers later concluded that both men likely arrived at their conclusions independent of one another.

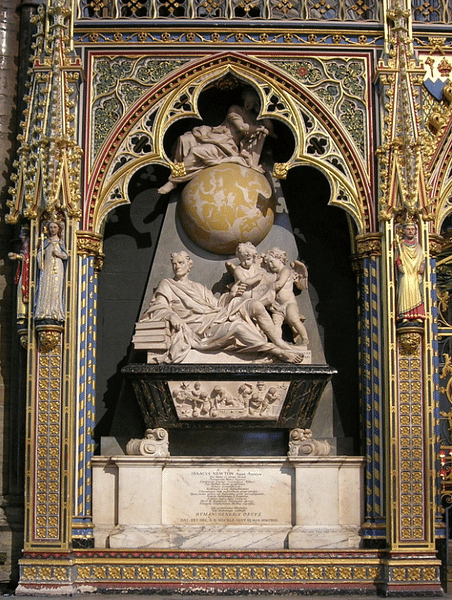

Death of Isaac Newton

Newton was also an ardent student of history and religious doctrines, and his writings on those subjects were compiled into multiple books that were published posthumously. Having never married, Newton spent his later years living with his niece at Cranbury Park near Winchester, England. He died in his sleep on March 31, 1727, and was buried in Westminster Abbey .

A giant even among the brilliant minds that drove the Scientific Revolution, Newton is remembered as a transformative scholar, inventor and writer. He eradicated any doubts about the heliocentric model of the universe by establishing celestial mechanics, his precise methodology giving birth to what is known as the scientific method. Although his theories of space-time and gravity eventually gave way to those of Albert Einstein , his work remains the bedrock on which modern physics was built.

Isaac Newton Quotes

- “If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of Giants.”

- “I can calculate the motion of heavenly bodies but not the madness of people.”

- “What we know is a drop, what we don't know is an ocean.”

- “Gravity explains the motions of the planets, but it cannot explain who sets the planets in motion.”

- “No great discovery was ever made without a bold guess.”

HISTORY Vault: Sir Isaac Newton: Gravity of Genius

Explore the life of Sir Isaac Newton, who laid the foundations for calculus and defined the laws of gravity.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Isaac Newton

Server costs fundraiser 2024.

Isaac Newton (1642-1727) was an English mathematician and physicist widely regarded as the single most important figure in the Scientific Revolution for his three laws of motion and universal law of gravity. Newton's laws became a fundamental foundation of physics, while his discovery that white light is made up of a rainbow of colours revolutionised the field of optics.

Isaac Newton was born on 25 December 1642. His family in Woolsthorpe, Lincolnshire, was of the yeomanry class, but it was clear that Isaac was destined for a career other than farming. Isaac's father died a few months before he was born, and his stepfather, a minister, died when he was 14. His mother was Hannah Ayscough, and her second husband insisted that Isaac be separated from his mother for a number of years. Some historians have read into this period of neglect the cause of Newton's notoriously prickly character and hypersensitivity to criticism later in life.

The young Isaac had a prodigious interest in all things mechanical, and he made several working models of his own, but he did not do particularly well at school. He was mischievous and once sent out into the night sky a series of candle-lit lanterns, which startled the local villagers into thinking a shower of comets was about to strike them down. An uncle of Isaac was adamant he was sent to study law at Trinity College, Cambridge, in June 1661. It was not law, though, but mathematics at which the young scholar excelled.

Isaac supplemented his orthodox education by taking private lessons with the mathematician and theologian Isaac Barrow (1630-1677). Barrow would later recommend Newton for his own soon-to-be-vacant chair at Trinity College. Newton graduated in April 1665, but any hope of a quick career launch was scuppered when there was an outbreak of the Black Death plague . Isaac was obliged to return to the family home in Woolthorpe for a year or more.

Newton's Approach to Knowledge

Isaac did not waste his year of forced seclusion as he launched into a series of scientific investigations, so much so that he described 1665 to 1666 as his "year of wonder" (Burns, 217). Newton discovered "the binomial theory, the differential and integral calculus, and the refraction of light, and he began to work out the theory of universal gravitation" ( ibid ). Heady stuff. Newton was determined to use all manner of methodologies and thinking, from alchemy to mechanical philosophy , in order to find out scientific truths that can be expressed mathematically. To this end, he relentlessly squirrelled away kernels of ancient and contemporary knowledge, experimentation, and even lore in a few select and very private leather-bound volumes, thus preserving his findings for later consumption when his scientific theories became clearer. As Newton himself once stated in a private letter, "If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of giants" (Wootton, 341).

Newton was also a Protestant Christian (although an unorthodox one in private) and saw no conflict in his endeavours to explain why things happened the way they do in the physical world with the story of the Bible . Indeed, the imperfections of the physical world his theories proved all required, Newton said, a Creator to adjust them every now and then. Some Christians saw this as denying the perfection of the Creator, others saw it as support for having a Creator in the first place. For Newton, space was "an eminent effect of God ," and "he seems to have gone so far as to later identify space with the immensity of God, so that the biblical pronouncements that 'In Him we live, and move, and have our being' (Acts 17:28) was taken quite literally" (Henry, 89).

Like many thinkers of the time, Newton was convinced that great knowledge had been gained and then lost over the centuries and so careful research of past intellectual endeavours was essential in order to recapture this lost wisdom (known as prisca sapientia ). This belief in a lost or secret knowledge – a peculiar eccentricity for a scientist – may also explain why Newton was notoriously reticent to publish his own discoveries. He seemed to relish secrecy, just as was the tradition of the great alchemists of the Middle Ages. Fortunately for the progress of humanity, Newton did eventually make his ground-breaking research public.

Newton's Spectrum of Light

Newton did not find the esteemed Royal Society very receptive to his new ideas, particularly on optics, and so he got his foot in the door of that institution by designing a reflective telescope in 1668. This type of telescope used a curved mirror made of a tin and copper alloy, which improved the clarity of the image seen by reducing chromatic aberration, that is, when all colours fail to converge in a single point (a problem of glass lenses at the time). Newton's telescope had a magnification of 40 times and was ten times shorter than the standard refracting telescope of the same strength would have been. The Royal Society was hooked, and Newton was elected to that learned body in 1672; he then submitted his research on optics, which had, in fact, made his super-duper telescope possible.

Between 1666 and 1668, Newton had conducted optical experiments where he captured a narrow beam of light through an aperture, which was then projected onto a wall in a dark room. The light was made to shine through a prism. Others had done this sort of thing before, but, significantly, Newton put his prism near the hole and far from the wall on which was projected a block of rainbow colours: red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, and violet. Even more crucial – in what he called his experimentum crucis – Newton then had various colour beams of the split white light go through a second prism, and these left that second prism the same colour as they entered, i.e. they could not be split further. Newton was thus able to develop a new theory of light, which was that white light is made up of a spectrum of different colours, each with a different angle of refraction, just like a rainbow one could see in the sky after a shower of rain. In the rainbow in the sky, drops of water function as a prism, that is, the white light is refracted. Newton also discovered that in the tiny airspace between a lens and a sheet of glass, coloured concentric rings can be seen, and these are now called Newton's rings.

Newton's idea of heterogeneous light, published in Philosophical Transactions in 1672, went directly against the standard theory of the time, which was the inverse of Newton's. Champions of the standard theory included Robert Hooke (1635-1703), who dismissed Newton's theory and later even accused him of plagiarism (without foundation). Newton, who was "of somewhat paranoid temperament" (Burns, 73) and "socially dysfunctional" (Jardine, 36), promptly withdrew from the Royal Society and would not even accept its presidency until Hooke had departed this earth. In 1704, Newton finally published his work on light in detail in his Optics . It took some time for Newton's theory to become widely accepted, but it is now a cornerstone of the science of optics.

Newton's Law of Gravity

The German astronomer Johannes Kepler created the most accurate yet system of planetary astronomy, with the heavenly bodies moving in elliptical orbits around the Sun and not the traditional model of perfect circles as proposed by thinkers from Claudius Ptolemy (c. 100 to c. 170) to Nicolaus Copernicus (1473-1543). The discovery that the planets increased their speed as they drew closer to the Sun was essential for Newton to build his own work upon. Newton's law of gravity would provide the cause for Kepler's keen observations of elliptical planetary motions. Encouraged, both with words and money, by his good friend Edmund Halley (1656-1742), Newton finally presented his theory of gravity in Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy ( Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica ), published in 1687.

The effects of gravity have been known since antiquity. Ancient thinkers formed theories as to why objects fell to the ground, the most common being that this was because Earth was the very centre of the universe and so some mysterious force attracted all objects to the central point. Similarly, thinkers like Galileo Galilei (1564-1642) had pondered what kind of force was responsible for the Sun seemingly pulling orbiting planets more speedily to its centre the closer they got to it. Magnetism was often suggested as the answer, but many thinkers remained unconvinced.

An apple may not have actually fallen from a branch and hit Newton on the head, but it does seem that his observation of fruit falling set him pondering what force was involved and how to measure it. Newton had also noticed many other 'attractions' and 'repulsions' between many other objects and substances, and so he began to formulate a theory that could measure such phenomena and finally bring together (or at least reconcile) two ancient but often opposing strands of human thought: mechanics and mathematics.

In his Principia , Newton put forward his theory of universal gravitation, but first, he presented a system of mathematical laws, which became known as 'Newton's laws of motion', here summarised by W. E. Burns:

That there is an attractive force between bodies that varies with the inverse square of the distance between them – and Newton's three laws of motion – 1. a body at rest or in motion in a straight path will tend to stay in that state, 2. a change of motion in a body varies with the force impressed, and 3. each action has an equal and opposite reaction. (218)

Newton then presented his theory of gravity:

That between any two bodies in the universe there exists a force directly proportional to the product of the masses of the two bodies and inversely proportional to the square of their distance. (Burns, 245)

Newton's theory of gravity was universal because it applied to everything from spinning planets to the movement of comets to the tides of the sea to that apocryphal apple dropping from a tree. The law of gravity (actually called a 'law' by Newton only in his later Optics ) applied equally to terrestrial affairs and to the heavens. Newton could now make accurate predictions of the effects of gravity. This was a new science. Of course, not everyone immediately adopted Newton's theories. The mechanical philosophers and the Cartesian followers of René Descartes (1596-1650), for example, could not accept that one physical body can affect another body without something, a third element, touching the two. Put simply, gravity was rather mysterious, since nobody, not even Newton, knew where it came from, why it exists, and who or what ensures its persistence. Contemplation on this fact and the inference that these forces act without any consideration of humanity led in some ways to a disenchantment regarding a new and pitiless world, at least for those who did not believe that a god of some kind was behind it all.

Sign up for our free weekly email newsletter!

Recognition: The Greatest Scientist

Newton's work on gravity was ultimately well received, particularly in England , and he was made a fellow of Trinity College in 1687. Two years later, Newton became the Lucasian Professor of Mathematics there. A circle of devoted international followers sprang up around Newton, including the Swiss mathematician Nicolas Fatio de Duillier (1664-1753), who became very close to him. From 1688, Newton became ambitious to forge a political career. The scientist had hoped to move to London but suffered a nervous breakdown in 1693, perhaps because of the end of his relationship with Fatio de Duillier but certainly made worse by his chronic insomnia and possibly even a consequence of mercury poisoning, a key ingredient of Newton's experiments in alchemy. Recovered by 1696, Newton was made the warden of the royal mint in the Tower of London , which carried with it both prestige and a handsome salary. Newton, taking a hands-on approach which had not been required for what was, in effect, an honorary position, impressed his employers so much that he was made the mint master in 1699. He performed the role with remarkable dedication for the next 28 years, much to the chagrin of the countless counterfeiters he identified (who were then invariably hanged).

It was also in 1699 that Newton was appointed a member of the French Royal Academy of Sciences, the first foreigner to gain entry. In 1703, he was elected President of the Royal Society, and he used his position to skew the society's endeavours much more towards practical experimentation (as opposed to merely reading the academic papers of others) throughout his tenure, which ended in 1727. Less admirable was his ongoing feud with the German mathematician Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz , which significantly held back mathematics in Britain . Newton accused Leibniz of plagiarising his work on the calculus (a mathematical tool for calculating curves and their areas). In reality, both men had developed the calculus independently, and although most historians consider Newton to have got there first, Leibniz's version was superior. Newton was knighted by Anne, Queen of Great Britain (r. 1702-1714) in 1705, probably more for his service in the royal mint than his tremendous contribution to science, but, nevertheless, it was a memorable moment for all scientists past and present since he was the first to be so honoured.

Death & Legacy

Newton was famous in his own lifetime for his discoveries, as we have seen with his various appointments to prestigious institutions at home and abroad. Rather oddly for a man so associated with science, Newton spent his final years studying biblical prophecies, an area he believed was just as valid as scientific experimentation. Sir Isaac Newton died of kidney failure on 20 March 1727; he was 84 years old. He had never married and left no children. Newton was given a state funeral and buried in Westminster Abbey. Alexander Pope provided the memorable epitaph:

Nature and Nature's Laws lay hid by Night: GOD said, Let Newton be! And all was Light. (Wootton, 361)

Newton, in one of those statements he frequently made where one wonders if he is being genuinely modest, remarked upon his career and discoveries in the following terms:

I don't know what I may seem to the world but, as to myself, I seem to have been only like a boy playing on the sea-shore, and diverting myself in now and then finding a smoother pebble or a prettier shell than ordinary, whilst the great ocean of truth lay all undiscovered before me. (Gleick, 4)

There would be many more breakthroughs in science after Newton, but nothing as revolutionary as his work until the development in the 20th century of relativity and quantum physics.

There developed a definite movement, known as Newtonianism, which pushed the idea that scientific knowledge should be presented as a series of mathematical laws which could predict tendencies of motion in relation to hypothetical accelerative forces. In addition, because Newton's research was so complex and inaccessible to the majority, a great number of writers sprang up who simplified Newton's work so that it could be understood by the reasonably well-educated. Newtonianism gradually spread across Europe to become the dominant approach in universities and amongst intellectuals. Newton's approach to knowledge, spread to new minds by such thinkers as Voltaire (1694-1778) in his Elements of Newton's Philosophy (1738), was an important part of the Enlightenment movement, where the improvement of the human condition became the ultimate goal of philosophy and science, despite Newton having split those two disciplines apart forever. Even that great modern genius Albert Einstein (1879-1955), with his new theory of relativity, could not overthrow Newtonianism but only extend it to new and bold horizons. As Einstein once said of Newton: "He stands before us strong, certain, and alone" (Gleick, 9).

Subscribe to topic Related Content Books Cite This Work License

Bibliography

- Burns, William E. The Scientific Revolution in Global Perspective. Oxford University Press, 2015.

- Burns, William E. The Scientific Revolution. ABC-CLIO, 2001.

- Bynum, William F. & Browne, Janet & Porter, Roy. Dictionary of the History of Science . Princeton University Press, 1982.

- Gleick, James. Isaac Newton. Vintage Books, 2023.

- Henry. The Scientific Revolution and the Origins of Modern Science . Red Globe Press, 2008.

- Jardine, Lisa. Ingenious Pursuits. Anchor, 2000.

- Moran, Bruce T. Distilling Knowledge. Harvard University Press, 2005.

- Wootton, David. The Invention of Science. Penguin UK, 2023.

About the Author

Translations

We want people all over the world to learn about history. Help us and translate this definition into another language!

Questions & Answers

What is isaac newton famous for, was isaac newton an alchemist, what was the significance of newton's law of gravity, related content.

Astronomy in the Scientific Revolution

Scientific Revolution

Jesuit Influence on Post-medieval Chinese Astronomy

Greek Mathematics

Isaac I Komnenos

The Foundation of the Royal Society

Free for the world, supported by you.

World History Encyclopedia is a non-profit organization. For only $5 per month you can become a member and support our mission to engage people with cultural heritage and to improve history education worldwide.

Recommended Books

Cite This Work

Cartwright, M. (2023, September 19). Isaac Newton . World History Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.worldhistory.org/Isaac_Newton/

Chicago Style

Cartwright, Mark. " Isaac Newton ." World History Encyclopedia . Last modified September 19, 2023. https://www.worldhistory.org/Isaac_Newton/.

Cartwright, Mark. " Isaac Newton ." World History Encyclopedia . World History Encyclopedia, 19 Sep 2023. Web. 12 Aug 2024.

License & Copyright

Submitted by Mark Cartwright , published on 19 September 2023. The copyright holder has published this content under the following license: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike . This license lets others remix, tweak, and build upon this content non-commercially, as long as they credit the author and license their new creations under the identical terms. When republishing on the web a hyperlink back to the original content source URL must be included. Please note that content linked from this page may have different licensing terms.

Isaac Newton, Mathematician and Scientist Essay (Biography)

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

Newton‘s early life, middle and late life, works cited.

Isaac Newton is one of the greatest historical figures who will remain the annals of history, because of his numerous contributions to different scientific fields such as mathematics and physics. As Hall (Para 1) argues, “Generally, people have always regarded Newton as one of the most influential theorists in the history of science”. Most of his scientific experiments and abstracts laid the foundation of the modern day scientific inventions, as he was able to prove and document different theoretical concepts.

For example, his publication “Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy,” is one of the best scientific reference materials in physics and mathematics. Newton is well remembered for his numerous scientific discoveries such the laws of gravity, differential and integral calculus, the working of a telescope, and the three laws of linear motion. In addition to science, Newton was also very religious, because of the numerous biblical hermeneutics and occult studies that he wrote in his late life (1).

Newton’s Early Life

Newton was born to Puritan parents Isaac Newton and Hannah Ayscough in 1643 in the county of Lincolnshire, England. He spent most of his childhood days with his grandmother, because his dad had passed away three months before he was born and he could not get along with his stepfather.

As During his early years of school, Newton schooled at the King’s School, Grantham, although it never lasted for long, because the passing away of his stepfather in 1659 forced his family to relocate to Woolsthorpe-by-Colsterworth; hence, making him to drop out of school. His stay in Woolsthorpe-by-Colsterworth was short-lived, because through the influence of King’s school master Henry Strokes, his mother allowed him to go back to school and finish his studies.

As a result of his exemplary performance in the King’s School, Newton got a chance of joining Trinity College, Cambridge on a sizar basis. In college, Newton was a very hardworking and fast learner, because in addition to reading the normal college curriculum materials that were based on Aristotle’s works, he was interested in reading more philosophical and astronomical works written by other philosophers such as Descartes and astronomers such as Galileo, and Thomas Hobes .

To a large extent, this laid the foundation for his later discoveries, because four years later in 1665, Newton invented the binomial theorem and came up with a mathematical theory, which he later modified to be called the infinitesimal calculus. The closure of Trinity College, Cambridge in the late 1665, because of the plague did not prevent Newton from advancing his studies on his own, as he continued with private studies at home.

Through his private studies Newton was able to discover numerous theories the primary ones being calculus, optics, the foundation of the theory of light and color, and the law of gravitation. Newton was very proud of his advancements, something that was evident in his words “ All this was in the two plague years of 1665 and 1666, for in those days I was in my prime of age for invention, and minded mathematics and philosophy more than at any time since,’ when college reopened (O’Connor and Robertson 1).

Newton’s middle Life

Upon the re-opening of his college in 1667, he was chosen as a minor fellow, and later as senior fellow when he embarked on his masters of Arts degree. In 1969, he was selected to replace Professor Isaac Barrow, who was the outgoing professor of Mathematics.

His appointment gave him more opportunities of improving his early works in optics, which led to the release of his first project paper on the nature of color in 1672, after being elected to the Royal Society. This marked the start of the numerous publications that Newton released later, although he faced numerous challenges and oppositions from one the leading science researchers, Robert Hook. Between 1670 and 1672 Newton also taught optics at Trinity College, Cambridge.

This enabled him to do further researches on the concept of refraction of light using glass prisms leading to his discovery on refraction of light and development of the first Newtonian telescope using mirrors. Although the 1678 emotional breakdown suffered by Newton was a major setback to his work, after recovering, he continued with his early researches which led to the publication of the Principia; a publication that elaborated on the laws of motion and the universal law of gravity.

In addition to this, the publication elaborated on some calculus laws primarily on geometrical analysis and some more explanations of the heliocentric theory of the solar system. This publication was followed by another publication that was the second edition of the Principia in 1713. This publication provided more explanations on the force of gravity and the force which made objects to be attracted to one another (Hatch 1).

Newton’s Late Life

His works in the Principia made Newton to a very respected and famous scientist of the time; hence, the nature of appointments, which he received in his late life. For example, in 1689 he was selected as the parliamentary representative of Cambridge; one of the highest power seats of the time. As if this was not enough, in 1703 Newton become the president of the Royal Society, a seat he maintained until his death and Later on in 1704, Newton released a publication named “Opticks” (Fowler 1).

The dawn of 1690’was a transitional period for Newton, as he ventured into the Bible World. As Hatch (1) argues “during this period Newton ventured into writing religious tracts with literal interpretation of the Bible.” Some of his writings included some works which questioned the reality behind the Trinity and the Chronology of Ancient Kingdoms Amended.

Newton’s Scientific Achievements

Newton was one of the most successful historical scientists, because of his numerous contributions to different fields of science such as optics, mathematics, geography, and physics. In mathematics Newton’s discoveries included the binomial theorem of analytical geometry, new methods of solving infinite series in calculus, and the inverse methods of fluxions.

In optic, Newton was one of the first individuals to perform the first experiments on the decomposition of light and the working of the telescope, because of his early discovery on separation of the white light. This enabled Newton to formulate the Corpuscular Light Theory and discover other properties of the white light.

In addition to this, Newton also made numerous discoveries in Physics and mechanics such gravitational force, the centripetal force, the theory of fluids, and the revolution of planetary bodies. Further, Newton was made numerous discoveries in Alchemy and Chemistry, most of which are documented in his numerous publications on different areas of Alchemy, most of which were based on scientific experiments on matter (Hatch 1).

Although in his later life his level of wit his wit reduced, as Hatch (Para 13) argues, “Newton continued to exercise strong influence on the advancement of science, because of his position in the Royal Society. Newton died at the age of eighty fours in 1727, leaving behind a legacy will always remembered in the history of humankind, because of his scientific works.

Fowler, Michael. Isaac Newton: Newton’s life . 2010. Web.

Hall, Alfred. Isaac Newton’s life. Isaac Newton Institute of mathematical Sciences . 2011. Web.

Hatch, Robert. Sir Isaac Newton. 1998. Web.

O ’ Connor, John and Robertson, Ernest. Sir Isaac Newton . 2000. Web.

- Catherine the Great: The Last Reigning Empress of Russia

- Life of a Japanese Warlord: Oda Nobunaga

- The Enlightenment Period in the Development of Culture

- History of the Telescope

- Isaac Newton and His Life

- Malcolm Baldrige Jr.: Hero of Quality Improvement

- Black Americans In The Westward Movement: The Key Figures

- Alexander the Great and the Hellenistic Legacy

- The Life and Music of Frederic Chopin

- The Evolution of the American Hero

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2018, August 23). Isaac Newton, Mathematician and Scientist. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-biography-of-isaac-newton/

"Isaac Newton, Mathematician and Scientist." IvyPanda , 23 Aug. 2018, ivypanda.com/essays/the-biography-of-isaac-newton/.

IvyPanda . (2018) 'Isaac Newton, Mathematician and Scientist'. 23 August.

IvyPanda . 2018. "Isaac Newton, Mathematician and Scientist." August 23, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-biography-of-isaac-newton/.

1. IvyPanda . "Isaac Newton, Mathematician and Scientist." August 23, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-biography-of-isaac-newton/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Isaac Newton, Mathematician and Scientist." August 23, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-biography-of-isaac-newton/.

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Isaac Newton

Isaac Newton (1642–1727) is best known for having invented the calculus in the mid to late 1660s (most of a decade before Leibniz did so independently, and ultimately more influentially) and for having formulated the theory of universal gravity — the latter in his Principia , the single most important work in the transformation of early modern natural philosophy into modern physical science. Yet he also made major discoveries in optics beginning in the mid-1660s and reaching across four decades; and during the course of his 60 years of intense intellectual activity he put no less effort into chemical and alchemical research and into theology and biblical studies than he put into mathematics and physics. He became a dominant figure in Britain almost immediately following publication of his Principia in 1687, with the consequence that “Newtonianism” of one form or another had become firmly rooted there within the first decade of the eighteenth century. His influence on the continent, however, was delayed by the strong opposition to his theory of gravity expressed by such leading figures as Christiaan Huygens and Leibniz, both of whom saw the theory as invoking an occult power of action at a distance in the absence of Newton's having proposed a contact mechanism by means of which forces of gravity could act. As the promise of the theory of gravity became increasingly substantiated, starting in the late 1730s but especially during the 1740s and 1750s, Newton became an equally dominant figure on the continent, and “Newtonianism,” though perhaps in more guarded forms, flourished there as well. What physics textbooks now refer to as “Newtonian mechanics” and “Newtonian science” consists mostly of results achieved on the continent between 1740 and 1800.

1.1 Newton's Early Years

1.2 newton's years at cambridge prior to principia, 1.3 newton's final years at cambridge, 1.4 newton's years in london and his final years, 2. newton's work and influence, primary sources, secondary sources, other internet resources, related entries, 1. newton's life.

Newton's life naturally divides into four parts: the years before he entered Trinity College, Cambridge in 1661; his years in Cambridge before the Principia was published in 1687; a period of almost a decade immediately following this publication, marked by the renown it brought him and his increasing disenchantment with Cambridge; and his final three decades in London, for most of which he was Master of the Mint. While he remained intellectually active during his years in London, his legendary advances date almost entirely from his years in Cambridge. Nevertheless, save for his optical papers of the early 1670s and the first edition of the Principia , all his works published before he died fell within his years in London. [ 1 ]

Newton was born into a Puritan family in Woolsthorpe, a small village in Linconshire near Grantham, on 25 December 1642 (old calendar), a few days short of one year after Galileo died. Isaac's father, a farmer, died two months before Isaac was born. When his mother Hannah married the 63 year old Barnabas Smith three years later and moved to her new husband's residence, Isaac was left behind with his maternal grandparents. (Isaac learned to read and write from his maternal grandmother and mother, both of whom, unlike his father, were literate.) Hannah returned to Woolsthorpe with three new children in 1653, after Smith died. Two years later Isaac went to boarding school in Grantham, returning full time to manage the farm, not very successfully, in 1659. Hannah's brother, who had received an M.A. from Cambridge, and the headmaster of the Grantham school then persuaded his mother that Isaac should prepare for the university. After further schooling at Grantham, he entered Trinity College in 1661, somewhat older than most of his classmates.

These years of Newton's youth were the most turbulent in the history of England. The English Civil War had begun in 1642, King Charles was beheaded in 1649, Oliver Cromwell ruled as lord protector from 1653 until he died in 1658, followed by his son Richard from 1658 to 1659, leading to the restoration of the monarchy under Charles II in 1660. How much the political turmoil of these years affected Newton and his family is unclear, but the effect on Cambridge and other universities was substantial, if only through unshackling them for a period from the control of the Anglican Catholic Church. The return of this control with the restoration was a key factor inducing such figures as Robert Boyle to turn to Charles II for support for what in 1660 emerged as the Royal Society of London. The intellectual world of England at the time Newton matriculated to Cambridge was thus very different from what it was when he was born.

Newton's initial education at Cambridge was classical, focusing (primarily through secondary sources) on Aristotlean rhetoric, logic, ethics, and physics. By 1664, Newton had begun reaching beyond the standard curriculum, reading, for example, the 1656 Latin edition of Descartes's Opera philosophica , which included the Meditations , Discourse on Method , the Dioptrics , and the Principles of Philosophy . By early 1664 he had also begun teaching himself mathematics, taking notes on works by Oughtred, Viète, Wallis, and Descartes — the latter via van Schooten's Latin translation, with commentary, of the Géométrie . Newton spent all but three months from the summer of 1665 until the spring of 1667 at home in Woolsthorpe when the university was closed because of the plague. This period was his so-called annus mirabilis . During it, he made his initial experimental discoveries in optics and developed (independently of Huygens's treatment of 1659) the mathematical theory of uniform circular motion, in the process noting the relationship between the inverse-square and Kepler's rule relating the square of the planetary periods to the cube of their mean distance from the Sun. Even more impressively, by late 1666 he had become de facto the leading mathematician in the world, having extended his earlier examination of cutting-edge problems into the discovery of the calculus, as presented in his tract of October 1666. He returned to Trinity as a Fellow in 1667, where he continued his research in optics, constructing his first reflecting telescope in 1669, and wrote a more extended tract on the calculus “De Analysi per Æquations Numero Terminorum Infinitas” incorporating new work on infinite series. On the basis of this tract Isaac Barrow recommended Newton as his replacement as Lucasian Professor of Mathematics, a position he assumed in October 1669, four and a half years after he had received his Bachelor of Arts.

Over the course of the next fifteen years as Lucasian Professor Newton presented his lectures and carried on research in a variety of areas. By 1671 he had completed most of a treatise length account of the calculus, [ 2 ] which he then found no one would publish. This failure appears to have diverted his interest in mathematics away from the calculus for some time, for the mathematical lectures he registered during this period mostly concern algebra. (During the early 1680s he undertook a critical review of classical texts in geometry, a review that reduced his view of the importance of symbolic mathematics.) His lectures from 1670 to 1672 concerned optics, with a large range of experiments presented in detail. Newton went public with his work in optics in early 1672, submitting material that was read before the Royal Society and then published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society . This led to four years of exchanges with various figures who challenged his claims, including both Robert Hooke and Christiaan Huygens — exchanges that at times exasperated Newton to the point that he chose to withdraw from further public exchanges in natural philosophy. Before he largely isolated himself in the late 1670s, however, he had also engaged in a series of sometimes long exchanges in the mid 1670s, most notably with John Collins (who had a copy of “De Analysi”) and Leibniz, concerning his work on the calculus. So, though they remained unpublished, Newton's advances in mathematics scarcely remained a secret.

This period as Lucasian Professor also marked the beginning of his more private researches in alchemy and theology. Newton purchased chemical apparatus and treatises in alchemy in 1669, with experiments in chemistry extending across this entire period. The issue of the vows Newton might have to take in conjunction with the Lucasian Professorship also appears to have precipitated his study of the doctrine of the Trinity, which opened the way to his questioning the validity of a good deal more doctrine central to the Roman and Anglican Churches.

Newton showed little interest in orbital astronomy during this period until Hooke initiated a brief correspondence with him in an effort to solicit material for the Royal Society at the end of November 1679, shortly after Newton had returned to Cambridge following the death of his mother. Among the several problems Hooke proposed to Newton was the question of the trajectory of a body under an inverse-square central force:

It now remaines to know the proprietys of a curve Line (not circular nor concentricall) made by a centrall attractive power which makes the velocitys of Descent from the tangent Line or equall straight motion at all Distances in a Duplicate proportion to the Distances Reciprocally taken. I doubt not but that by your excellent method you will easily find out what the Curve must be, and it proprietys, and suggest a physicall Reason of this proportion. [ 3 ]

Newton apparently discovered the systematic relationship between conic-section trajectories and inverse-square central forces at the time, but did not communicate it to anyone, and for reasons that remain unclear did not follow up this discovery until Halley, during a visit in the summer of 1684, put the same question to him. His immediate answer was, an ellipse; and when he was unable to produce the paper on which he had made this determination, he agreed to forward an account to Halley in London. Newton fulfilled this commitment in November by sending Halley a nine-folio-page manuscript, “De Motu Corporum in Gyrum” (“On the Motion of Bodies in Orbit”), which was entered into the Register of the Royal Society in early December 1684. The body of this tract consists of ten deduced propositions — three theorems and seven problems — all of which, along with their corollaries, recur in important propositions in the Principia .

Save for a few weeks away from Cambridge, from late 1684 until early 1687, Newton concentrated on lines of research that expanded the short ten-proposition tract into the 500 page Principia , with its 192 derived propositions. Initially the work was to have a two book structure, but Newton subsequently shifted to three books, and replaced the original version of the final book with one more mathematically demanding. The manuscript for Book 1 was sent to London in the spring of 1686, and the manuscripts for Books 2 and 3, in March and April 1687, respectively. The roughly three hundred copies of the Principia came off the press in the summer of 1687, thrusting the 44 year old Newton into the forefront of natural philosophy and forever ending his life of comparative isolation.

The years between the publication of the Principia and Newton's permanent move to London in 1696 were marked by his increasing disenchantment with his situation in Cambridge. In January 1689, following the Glorious Revolution at the end of 1688, he was elected to represent Cambridge University in the Convention Parliament, which he did until January 1690. During this time he formed friendships with John Locke and Nicolas Fatio de Duillier, and in the summer of 1689 he finally met Christiaan Huygens face to face for two extended discussions. Perhaps because of disappointment with Huygens not being convinced by the argument for universal gravity, in the early 1690s Newton initiated a radical rewriting of the Principia . During these same years he wrote (but withheld) his principal treatise in alchemy, Praxis ; he corresponded with Richard Bentley on religion and allowed Locke to read some of his writings on the subject; he once again entered into an effort to put his work on the calculus in a form suitable for publication; and he carried out experiments on diffraction with the intent of completing his Opticks , only to withhold the manuscript from publication because of dissatisfaction with its treatment of diffraction. The radical revision of the Principia became abandoned by 1693, during the middle of which Newton suffered, by his own testimony, what in more recent times would be called a nervous breakdown. In the two years following his recovery that autumn, he continued his experiments in chymistry and he put substantial effort into trying to refine and extend the gravity-based theory of the lunar orbit in the Principia , but with less success than he had hoped.

Throughout these years Newton showed interest in a position of significance in London, but again with less success than he had hoped until he accepted the relatively minor position of Warden of the Mint in early 1696, a position he held until he became Master of the Mint at the end of 1699. He again represented Cambridge University in Parliament for 16 months, beginning in 1701, the year in which he resigned his Fellowship at Trinity College and the Lucasian Professorship. He was elected President of the Royal Society in 1703 and was knighted by Queen Anne in 1705.

Newton thus became a figure of imminent authority in London over the rest of his life, in face-to-face contact with individuals of power and importance in ways that he had not known in his Cambridge years. His everyday home life changed no less dramatically when his extraordinarily vivacious teenage niece, Catherine Barton, the daughter of his half-sister Hannah, moved in with him shortly after he moved to London, staying until she married John Conduitt in 1717, and after that remaining in close contact. (It was through her and her husband that Newton's papers came down to posterity.) Catherine was socially prominent among the powerful and celebrated among the literati for the years before she married, and her husband was among the wealthiest men of London.

The London years saw Newton embroiled in some nasty disputes, probably made the worse by the ways in which he took advantage of his position of authority in the Royal Society. In the first years of his Presidency he became involved in a dispute with John Flamsteed in which he and Halley, long ill-disposed toward the Flamsteed, violated the trust of the Royal Astronomer, turning him into a permanent enemy. Ill feelings between Newton and Leibniz had been developing below the surface from even before Huygens had died in 1695, and they finally came to a head in 1710 when John Keill accused Leibniz in the Philosophical Transactions of having plagiarized the calculus from Newton and Leibniz, a Fellow of the Royal Society since 1673, demanded redress from the Society. The Society's 1712 published response was anything but redress. Newton not only was a dominant figure in this response, but then published an outspoken anonymous review of it in 1715 in the Philosophical Transactions . Leibniz and his colleagues on the Continent had never been comfortable with the Principia and its implication of action at a distance. With the priority dispute this attitude turned into one of open hostility toward Newton's theory of gravity — a hostility that was matched in its blindness by the fervor of acceptance of the theory in England. The public elements of the priority dispute had the effect of expanding a schism between Newton and Leibniz into a schism between the English associated with the Royal Society and the group who had been working with Leibniz on the calculus since the 1690s, including most notably Johann Bernoulli, and this schism in turn transformed into one between the conduct of science and mathematics in England versus the Continent that persisted long after Leibniz died in 1716.

Although Newton obviously had far less time available to devote to solitary research during his London years than he had had in Cambridge, he did not entirely cease to be productive. The first (English) edition of his Opticks finally appeared in 1704, appended to which were two mathematical treatises, his first work on the calculus to appear in print. This edition was followed by a Latin edition in 1706 and a second English edition in 1717, each containing important Queries on key topics in natural philosophy beyond those in its predecessor. Other earlier work in mathematics began to appear in print, including a work on algebra, Arithmetica Universalis , in 1707 and “De Analysi” and a tract on finite differences, “Methodis differentialis” in 1711. The second edition of the Principia , on which Newton had begun work at the age of 66 in 1709, was published in 1713, with a third edition in 1726. Though the original plan for a radical restructuring had long been abandoned, the fact that virtually every page of the Principia received some modifications in the second edition shows how carefully Newton, often prodded by his editor Roger Cotes, reconsidered everything in it; and important parts were substantially rewritten not only in response to Continental criticisms, but also because of new data, including data from experiments on resistance forces carried out in London. Focused effort on the third edition began in 1723, when Newton was 80 years old, and while the revisions are far less extensive than in the second edition, it does contain substantive additions and modfications, and it surely has claim to being the edition that represents his most considered views.

Newton died on 20 March 1727 at the age of 84. His contemporaries' conception of him nevertheless continued to expand as a consequence of various posthumous publications, including The Chronology of Ancient Kingdoms Amended (1728); the work originally intended to be the last book of the Principia , The System of the World (1728, in both English and Latin); Observations upon the Prophecies of Daniel and the Apocalypse of St. John (1733); A Treatise of the Method of Fluxions and Infinite Series (1737); A Dissertation upon the Sacred Cubit of the Jews (1737), and Four Letters from Sir Isaac Newton to Doctor Bentley concerning Some Arguments in Proof of a Deity (1756). Even then, however, the works that had been published represented only a limited fraction of the total body of papers that had been left in the hands of Catherine and John Conduitt. The five volume collection of Newton's works edited by Samuel Horsley (1779–85) did not alter this situation. Through the marriage of the Conduitts' daughter Catherine and subsequent inheritance, this body of papers came into the possession of Lord Portsmouth, who agreed in 1872 to allow it to be reviewed by scholars at Cambridge University (John Couch Adams, George Stokes, H. R. Luard, and G. D. Liveing). They issued a catalogue in 1888, and the university then retained all the papers of a scientific character. With the notable exception of W. W. Rouse Ball, little work was done on the scientific papers before World War II. The remaining papers were returned to Lord Portsmouth, and then ultimately sold at auction in 1936 to various parties. Serious scholarly work on them did not get underway until the 1970s, and much remains to be done on them.

Three factors stand in the way of giving an account of Newton's work and influence. First is the contrast between the public Newton, consisting of publications in his lifetime and in the decade or two following his death, and the private Newton, consisting of his unpublished work in math and physics, his efforts in chymistry — that is, the 17th century blend of alchemy and chemistry — and his writings in radical theology — material that has become public mostly since World War II. Only the public Newton influenced the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, yet any account of Newton himself confined to this material can at best be only fragmentary. Second is the contrast, often shocking, between the actual content of Newton's public writings and the positions attributed to him by others, including most importantly his popularizers. The term “Newtonian” refers to several different intellectual strands unfolding in the eighteenth century, some of them tied more closely to Voltaire, Pemberton, and Maclaurin — or for that matter to those who saw themselves as extending his work, such as Clairaut, Euler, d'Alembert, Lagrange, and Laplace — than to Newton himself. Third is the contrast between the enormous range of subjects to which Newton devoted his full concentration at one time or another during the 60 years of his intellectual career — mathematics, optics, mechanics, astronomy, experimental chemistry, alchemy, and theology — and the remarkably little information we have about what drove him or his sense of himself. Biographers and analysts who try to piece together a unified picture of Newton and his intellectual endeavors often end up telling us almost as much about themselves as about Newton.