Best Active Verbs for Research Papers with Examples

What are active verbs.

Active verbs, often referred to as "action verbs," depict activities, processes, or occurrences. They energize sentences by illustrating direct actions, like "run," "write," or "discover." In contrast, linking verbs connect the subject of a sentence to its complement, offering information about the subject rather than denoting an action. The most common linking verb is the "be" verb (am, is, are, was, were, etc.), which often describes a state of being. While active verbs demonstrate direct activity or motion, linking and "be" verbs serve as bridges, revealing relations or states rather than actions.

While linking verbs are necessary to states facts or show connections between two or more items, subjects, or ideas, active verbs usually have a more specific meaning that can explain these connections and actions with greater accuracy. And they captivate the reader’s attention! (See what I did there?)

Why are active verbs important to use in research papers?

Using active verbs in academic papers enhances clarity and precision, propelling the narrative forward and making your arguments more compelling. Active verbs provide clear agents of action, making your assertions clearer and more vigorous. This dynamism ensures readers grasp the research's core points and its implications.

For example, using an active vs passive voice sentence can create more immediate connection and clarity for the reader. Instead of writing "The experiment was conducted by the team," one could write, "The team conducted the experiment."

Similarly, rather than stating "Results were analyzed," a more direct approach would be "We analyzed the results." Such usage not only shortens sentences but also centers the focus, making the statements about the research more robust and persuasive.

Best Active Verbs for Academic & Research Papers

When writing research papers , choose active verbs that clarify and energize writing: the Introduction section "presents" a hypothesis, the Methods section "describes" your study procedures, the Results section "shows" the findings, and the Discussion section "argues" the wider implications. Active language makes each section more direct and engaging, effectively guiding readers through the study's journey—from initial inquiry to final conclusions—while highlighting the researcher's active role in the scholarly exploration.

Active verbs to introduce a research topic

Using active verbs in the Introduction section of a research paper sets a strong foundation for the study, indicating the actions taken by researchers and the direction of their inquiry.

Stresses a key stance or finding, especially when referring to published literature.

Indicates a thorough investigation into a research topic.

Draws attention to important aspects or details of the study topic you are addressing.

Questions or disputes established theories or beliefs, especially in previous published studies.

Highlights and describes a point of interest or importance.

Inspects or scrutinizes a subject closely.

Sets up the context or background for the study.

Articulates

Clearly expresses an idea or theory. Useful when setting up a research problem statement .

Makes something clear by explaining it in more detail.

Active verbs to describe your study approach

Each of these verbs indicates a specific, targeted action taken by researchers to advance understanding of their study's topic, laying out the groundwork in the Introduction for what the study aims to accomplish and how.

Suggests a theory, idea, or method for consideration.

Investigates

Implies a methodical examination of the subject.

Indicates a careful evaluation or estimation of a concept.

Suggests a definitive or conclusive finding or result.

Indicates the measurement or expression of an element in numerical terms.

Active verbs to describe study methods

The following verbs express a specific action in the methodology of a research study, detailing how researchers execute their investigations and handle data to derive meaningful conclusions.

Implies carrying out a planned process or experiment. Often used to refer to methods in other studies the literature review section .

Suggests putting a plan or technique into action.

Indicates the use of tools, techniques, or information for a specific purpose.

Denotes the determination of the quantity, degree, or capacity of something.

Refers to the systematic gathering of data or samples.

Involves examining data or details methodically to uncover relationships, patterns, or insights.

Active verbs for a hypothesis or problem statement

Each of the following verbs initiates a hypothesis or statement of the problem , indicating different levels of certainty and foundations of reasoning, which the research then aims to explore, support, or refute.

Suggests a hypothesis or a theory based on limited evidence as a starting point for further investigation.

Proposes a statement or hypothesis that is assumed to be true, and from which a conclusion can be drawn.

Attempts to identify

Conveys an explicit effort to identify or isolate a specific element or relationship in the study.

Foretells a future event or outcome based on a theory or observation.

Theorizes or puts forward a consideration about a subject without firm evidence.

Proposes an idea or possibility based on indirect or incomplete evidence.

Active verbs used to interpret and explain study results

In the Discussion section , the findings of your study are interpreted and explained to the reader before moving on to study implications and limitations . These verbs communicate the outcomes of the research in a precise and assertive manner, conveying how the data aligns with the expectations and hypotheses laid out earlier in the paper.

Shows or unveils findings from the data.

Demonstrates

Clearly shows the result of an experiment or study, often implying evidence of a cause-and-effect relationship.

Illustrates

Shows or presentes a particular result or trend.

Provides evidence in favor of a theory or hypothesis.

Establishes the truth or validity of an anticipated outcome or theory.

Visually presents data, often implying the use of figures or tables.

Active verbs to discuss study implications

In the discussion of study implications, these verbs help to weave the results into a broader context, suggesting relevance, highlighting importance, and pointing out potential consequences within the respective field of research.

Proposes a possible interpretation or implication without making a definitive statement.

Points to broader consequences or significances hinted at by the results.

Indicates a logical consequence or a meaning that is not explicitly stated.

Strengthens the validity or importance of a concept or finding.

Emphasizes certain findings and their broader ramifications.

Underscores

Underlines or emphasizes the significance or seriousness of an implication.

Active verbs to discuss study limitations

Discussing study limitations with these verbs allows researchers to maintain transparency about their study's weaknesses, thus providing a clearer picture of the context and reliability of the research findings.

Acknowledges

Recognizes the existence of potential weaknesses or restrictions in the study.

Directly confronts a specific limitation and often discusses ways it has been mitigated.

Makes an observation of a limitation that could affect the interpretation of the results.

Reflects on or thinks about a limitation in the context of the study's impact or scope.

Points out and describes a specific limitation.

Makes known or reveals a limitation that could have an effect on the study's conclusions.

Active verbs for the Conclusion section

In the Conclusion section , these verbs are pivotal in crystallizing the core findings, implications, and the future trajectory of research initiated by the study.

Signifies drawing a final inference or judgement based on the results.

Provides a brief statement of the main points of the research findings.

States positively or asserts the validity of the findings.

Advises on a course of action based on the results obtained.

Highlights the importance or significance of the research outcomes.

Use an AI Grammar Checker to Correct Your Research Verbs

While lists like these will certainly help you improve your writing in any academic paper, it can still be a good idea to revise your paper using an AI writing assistant during the drafting process, and with professional editing services before submitting your work to journals.

Wordvice’s AI Proofreading Tool , AI Paraphrasing Tool , AI Summarizer , AI Translator , AI Grammar Checker , AI Plagiarism Checker , and AI Detector are ideal for enhancing your academic papers. And with our professional editing services, including academic proofreading and paper editing services, you get high-quality English editing from experts in your paper’s subject area.

Get in Touch with CCC’s Learning Commons

Active verbs, active verbs for discussing ideas.

Use these lists for word variation when writing a research-based, analytical, or argumentative paper. However, be careful: there are no perfect synonyms. These words are not necessarily interchangeable.

| Changes“ | |||||||

| larifies | |||||||

| xpands on | |||||||

| xpounds on | |||||||

| pass | |||||||

| validates | |||||||

| account | |||||||

Explanation and Examples

Why should I vary my verb choice?

Mark Twain once remarked , “The difference between the right word and the almost right word is the difference between lightning and a lightning bug.” Stronger diction (word choice) can result in a more interesting, vibrant, and sophisticated-sounding paper, but, more importantly, it will lead to clearer and more precise communication to your reader. Experiment with different words to discover and then state exactly what you mean!

What are the functions of these kinds of verbs?

The verbs on this handout offer a stronger link between your ideas and your source material. While the se kinds of verb s i ntroduce the supporting ideas and information, they also begin to indicate the relationship the quoted or paraphrased source material has with your larger point.

- B land and generic : Carol Dweck says , “ It is the belief that intelligence can be developed that opens students to a love of learning.”

- A more specific connection: Carol Dweck suggests , “ It is the belief that intelligence can be developed that opens students to a love of learning.”

- A stronger point argued : Carol Dweck emphasizes , “ It is the belief that intelligence can be developed that opens students to a love of learning.”

- The final, summative point: Carol Dweck concludes , “ It is the belief that intelligence can be developed that opens students to a love of learning.”

See the differences? Still, you should be careful to explain this significance or relevance more completely after using the source material.

You might imagine this like a “sandwich” within your paragraph. There might be several of these “ sandwiches ” within one body paragraph:

- Signal phrase or sentence with an active verb to introduce the source material (sometimes called a “lead-in”).

- Source material either paraphrased or directly quoted.

- Explanation of the significance / connection between that material and your larger point.

Here are some models that show effective ways of creating that “top bun ” of your “ sandwich. ” It would be followed by more evidence form you source, either paraphrased or quoted (middle layer), and then concluded with explanation of the source material’s significance (“bottom bun”):

- In his book The Status Syndrome , Jon Marmot hypothesizes that social class determines life outcomes (35).

- Paul Sawyer argues that geothermal energy is a wise alternative by highlighting several of its environmen tal and economic benefits (21-30).

- In the article “Impossibilities,” a professional educator ponders , “How does one teach when no one wants to learn?” ( Inayatullah 151).

- I n the article “Impossibilities,” a professional educator investigates a compell ing question: “How does one teach when no one wants to learn?” ( Inayatullah 151).

- Adaptations for format / ADA compliance. Authored by : Dann Coble. Provided by : Corning Community College. License : CC0: No Rights Reserved

- Authored by : Keith Ward. Provided by : Corning Community College. License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

Privacy Policy

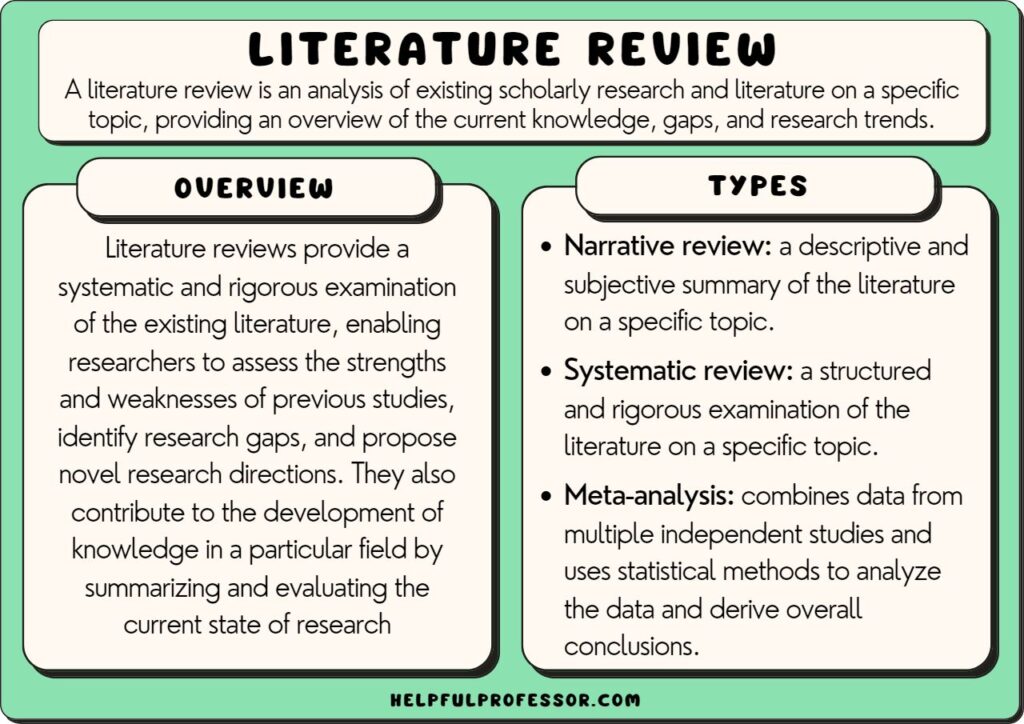

15 Literature Review Examples

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

Learn about our Editorial Process

Literature reviews are a necessary step in a research process and often required when writing your research proposal . They involve gathering, analyzing, and evaluating existing knowledge about a topic in order to find gaps in the literature where future studies will be needed.

Ideally, once you have completed your literature review, you will be able to identify how your research project can build upon and extend existing knowledge in your area of study.

Generally, for my undergraduate research students, I recommend a narrative review, where themes can be generated in order for the students to develop sufficient understanding of the topic so they can build upon the themes using unique methods or novel research questions.

If you’re in the process of writing a literature review, I have developed a literature review template for you to use – it’s a huge time-saver and walks you through how to write a literature review step-by-step:

Get your time-saving templates here to write your own literature review.

Literature Review Examples

For the following types of literature review, I present an explanation and overview of the type, followed by links to some real-life literature reviews on the topics.

1. Narrative Review Examples

Also known as a traditional literature review, the narrative review provides a broad overview of the studies done on a particular topic.

It often includes both qualitative and quantitative studies and may cover a wide range of years.

The narrative review’s purpose is to identify commonalities, gaps, and contradictions in the literature .

I recommend to my students that they should gather their studies together, take notes on each study, then try to group them by themes that form the basis for the review (see my step-by-step instructions at the end of the article).

Example Study

Title: Communication in healthcare: a narrative review of the literature and practical recommendations

Citation: Vermeir, P., Vandijck, D., Degroote, S., Peleman, R., Verhaeghe, R., Mortier, E., … & Vogelaers, D. (2015). Communication in healthcare: a narrative review of the literature and practical recommendations. International journal of clinical practice , 69 (11), 1257-1267.

Source: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/ijcp.12686

Overview: This narrative review analyzed themes emerging from 69 articles about communication in healthcare contexts. Five key themes were found in the literature: poor communication can lead to various negative outcomes, discontinuity of care, compromise of patient safety, patient dissatisfaction, and inefficient use of resources. After presenting the key themes, the authors recommend that practitioners need to approach healthcare communication in a more structured way, such as by ensuring there is a clear understanding of who is in charge of ensuring effective communication in clinical settings.

Other Examples

- Burnout in United States Healthcare Professionals: A Narrative Review (Reith, 2018) – read here

- Examining the Presence, Consequences, and Reduction of Implicit Bias in Health Care: A Narrative Review (Zestcott, Blair & Stone, 2016) – read here

- A Narrative Review of School-Based Physical Activity for Enhancing Cognition and Learning (Mavilidi et al., 2018) – read here

- A narrative review on burnout experienced by medical students and residents (Dyrbye & Shanafelt, 2015) – read here

2. Systematic Review Examples

This type of literature review is more structured and rigorous than a narrative review. It involves a detailed and comprehensive plan and search strategy derived from a set of specified research questions.

The key way you’d know a systematic review compared to a narrative review is in the methodology: the systematic review will likely have a very clear criteria for how the studies were collected, and clear explanations of exclusion/inclusion criteria.

The goal is to gather the maximum amount of valid literature on the topic, filter out invalid or low-quality reviews, and minimize bias. Ideally, this will provide more reliable findings, leading to higher-quality conclusions and recommendations for further research.

You may note from the examples below that the ‘method’ sections in systematic reviews tend to be much more explicit, often noting rigid inclusion/exclusion criteria and exact keywords used in searches.

Title: The importance of food naturalness for consumers: Results of a systematic review

Citation: Roman, S., Sánchez-Siles, L. M., & Siegrist, M. (2017). The importance of food naturalness for consumers: Results of a systematic review. Trends in food science & technology , 67 , 44-57.

Source: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S092422441730122X

Overview: This systematic review included 72 studies of food naturalness to explore trends in the literature about its importance for consumers. Keywords used in the data search included: food, naturalness, natural content, and natural ingredients. Studies were included if they examined consumers’ preference for food naturalness and contained empirical data. The authors found that the literature lacks clarity about how naturalness is defined and measured, but also found that food consumption is significantly influenced by perceived naturalness of goods.

- A systematic review of research on online teaching and learning from 2009 to 2018 (Martin, Sun & Westine, 2020) – read here

- Where Is Current Research on Blockchain Technology? (Yli-Huumo et al., 2016) – read here

- Universities—industry collaboration: A systematic review (Ankrah & Al-Tabbaa, 2015) – read here

- Internet of Things Applications: A Systematic Review (Asghari, Rahmani & Javadi, 2019) – read here

3. Meta-analysis

This is a type of systematic review that uses statistical methods to combine and summarize the results of several studies.

Due to its robust methodology, a meta-analysis is often considered the ‘gold standard’ of secondary research , as it provides a more precise estimate of a treatment effect than any individual study contributing to the pooled analysis.

Furthermore, by aggregating data from a range of studies, a meta-analysis can identify patterns, disagreements, or other interesting relationships that may have been hidden in individual studies.

This helps to enhance the generalizability of findings, making the conclusions drawn from a meta-analysis particularly powerful and informative for policy and practice.

Title: Cholesterol and Alzheimer’s Disease Risk: A Meta-Meta-Analysis

Citation: Sáiz-Vazquez, O., Puente-Martínez, A., Ubillos-Landa, S., Pacheco-Bonrostro, J., & Santabárbara, J. (2020). Cholesterol and Alzheimer’s disease risk: a meta-meta-analysis. Brain sciences, 10(6), 386.

Source: https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci10060386

O verview: This study examines the relationship between cholesterol and Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Researchers conducted a systematic search of meta-analyses and reviewed several databases, collecting 100 primary studies and five meta-analyses to analyze the connection between cholesterol and Alzheimer’s disease. They find that the literature compellingly demonstrates that low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels significantly influence the development of Alzheimer’s disease.

- The power of feedback revisited: A meta-analysis of educational feedback research (Wisniewski, Zierer & Hattie, 2020) – read here

- How Much Does Education Improve Intelligence? A Meta-Analysis (Ritchie & Tucker-Drob, 2018) – read here

- A meta-analysis of factors related to recycling (Geiger et al., 2019) – read here

- Stress management interventions for police officers and recruits (Patterson, Chung & Swan, 2014) – read here

Other Types of Reviews

- Scoping Review: This type of review is used to map the key concepts underpinning a research area and the main sources and types of evidence available. It can be undertaken as stand-alone projects in their own right, or as a precursor to a systematic review.

- Rapid Review: This type of review accelerates the systematic review process in order to produce information in a timely manner. This is achieved by simplifying or omitting stages of the systematic review process.

- Integrative Review: This review method is more inclusive than others, allowing for the simultaneous inclusion of experimental and non-experimental research. The goal is to more comprehensively understand a particular phenomenon.

- Critical Review: This is similar to a narrative review but requires a robust understanding of both the subject and the existing literature. In a critical review, the reviewer not only summarizes the existing literature, but also evaluates its strengths and weaknesses. This is common in the social sciences and humanities .

- State-of-the-Art Review: This considers the current level of advancement in a field or topic and makes recommendations for future research directions. This type of review is common in technological and scientific fields but can be applied to any discipline.

How to Write a Narrative Review (Tips for Undergrad Students)

Most undergraduate students conducting a capstone research project will be writing narrative reviews. Below is a five-step process for conducting a simple review of the literature for your project.

- Search for Relevant Literature: Use scholarly databases related to your field of study, provided by your university library, along with appropriate search terms to identify key scholarly articles that have been published on your topic.

- Evaluate and Select Sources: Filter the source list by selecting studies that are directly relevant and of sufficient quality, considering factors like credibility , objectivity, accuracy, and validity.

- Analyze and Synthesize: Review each source and summarize the main arguments in one paragraph (or more, for postgrad). Keep these summaries in a table.

- Identify Themes: With all studies summarized, group studies that share common themes, such as studies that have similar findings or methodologies.

- Write the Review: Write your review based upon the themes or subtopics you have identified. Give a thorough overview of each theme, integrating source data, and conclude with a summary of the current state of knowledge then suggestions for future research based upon your evaluation of what is lacking in the literature.

Literature reviews don’t have to be as scary as they seem. Yes, they are difficult and require a strong degree of comprehension of academic studies. But it can be feasibly done through following a structured approach to data collection and analysis. With my undergraduate research students (who tend to conduct small-scale qualitative studies ), I encourage them to conduct a narrative literature review whereby they can identify key themes in the literature. Within each theme, students can critique key studies and their strengths and limitations , in order to get a lay of the land and come to a point where they can identify ways to contribute new insights to the existing academic conversation on their topic.

Ankrah, S., & Omar, A. T. (2015). Universities–industry collaboration: A systematic review. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 31(3), 387-408.

Asghari, P., Rahmani, A. M., & Javadi, H. H. S. (2019). Internet of Things applications: A systematic review. Computer Networks , 148 , 241-261.

Dyrbye, L., & Shanafelt, T. (2016). A narrative review on burnout experienced by medical students and residents. Medical education , 50 (1), 132-149.

Geiger, J. L., Steg, L., Van Der Werff, E., & Ünal, A. B. (2019). A meta-analysis of factors related to recycling. Journal of environmental psychology , 64 , 78-97.

Martin, F., Sun, T., & Westine, C. D. (2020). A systematic review of research on online teaching and learning from 2009 to 2018. Computers & education , 159 , 104009.

Mavilidi, M. F., Ruiter, M., Schmidt, M., Okely, A. D., Loyens, S., Chandler, P., & Paas, F. (2018). A narrative review of school-based physical activity for enhancing cognition and learning: The importance of relevancy and integration. Frontiers in psychology , 2079.

Patterson, G. T., Chung, I. W., & Swan, P. W. (2014). Stress management interventions for police officers and recruits: A meta-analysis. Journal of experimental criminology , 10 , 487-513.

Reith, T. P. (2018). Burnout in United States healthcare professionals: a narrative review. Cureus , 10 (12).

Ritchie, S. J., & Tucker-Drob, E. M. (2018). How much does education improve intelligence? A meta-analysis. Psychological science , 29 (8), 1358-1369.

Roman, S., Sánchez-Siles, L. M., & Siegrist, M. (2017). The importance of food naturalness for consumers: Results of a systematic review. Trends in food science & technology , 67 , 44-57.

Sáiz-Vazquez, O., Puente-Martínez, A., Ubillos-Landa, S., Pacheco-Bonrostro, J., & Santabárbara, J. (2020). Cholesterol and Alzheimer’s disease risk: a meta-meta-analysis. Brain sciences, 10(6), 386.

Vermeir, P., Vandijck, D., Degroote, S., Peleman, R., Verhaeghe, R., Mortier, E., … & Vogelaers, D. (2015). Communication in healthcare: a narrative review of the literature and practical recommendations. International journal of clinical practice , 69 (11), 1257-1267.

Wisniewski, B., Zierer, K., & Hattie, J. (2020). The power of feedback revisited: A meta-analysis of educational feedback research. Frontiers in Psychology , 10 , 3087.

Yli-Huumo, J., Ko, D., Choi, S., Park, S., & Smolander, K. (2016). Where is current research on blockchain technology?—a systematic review. PloS one , 11 (10), e0163477.

Zestcott, C. A., Blair, I. V., & Stone, J. (2016). Examining the presence, consequences, and reduction of implicit bias in health care: a narrative review. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations , 19 (4), 528-542

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 10 Reasons you’re Perpetually Single

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 20 Montessori Toddler Bedrooms (Design Inspiration)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 21 Montessori Homeschool Setups

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 101 Hidden Talents Examples

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Perspect Med Educ

- v.7(2); 2018 Apr

Writing an effective literature review

Lorelei lingard.

Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry, Health Sciences Addition, Western University, London, Ontario Canada

In the Writer’s Craft section we offer simple tips to improve your writing in one of three areas: Energy, Clarity and Persuasiveness. Each entry focuses on a key writing feature or strategy, illustrates how it commonly goes wrong, teaches the grammatical underpinnings necessary to understand it and offers suggestions to wield it effectively. We encourage readers to share comments on or suggestions for this section on Twitter, using the hashtag: #how’syourwriting?

This Writer’s Craft instalment is the second in a two-part series that offers strategies for effectively presenting the literature review section of a research manuscript. This piece argues that citation is not just a technical practice but also a rhetorical one, and offers writers an expanded vocabulary for using citation to maximal effect.

Many writers think of citation as the formal system we use to avoid plagiarism and acknowledge others’ work. But citation is a much more nuanced practice than this. Not only does citation allow us to represent the source of knowledge, but it also allows us to position ourselves in relation to that knowledge, and to place that knowledge in relation to other knowledge . In short, citation is how we artfully tell the story of what the field knows, how it came to that knowledge, and where we stand in relation to it as we write the literature review section to frame our own work. Seen this way, citation is a sophisticated task, requiring in-depth knowledge of the literature in a domain.

Citation is more than just referencing; it is how we represent the social construction of knowledge in a field. A citation strategy is any indication in the text about the source and nature of knowledge. Consider the following passage, in which all citation strategies are italicized:

Despite years of effort to teach and enforce positive professional norms and standards, many reports of challenges to medical professionalism continue to appear, both in the medical and education literature and, often in reaction, in the lay press . 1,2,3,4,5 Examples of professional lapses dot the health care landscape: regulations are thwarted, records are falsified, patients are ignored, colleagues are berated. 2,4,6 The medical profession has articulated its sense of what professionalism is in a number of important position statements . 7,8 These statements tend to be built upon abstracted principles and values, such as the taxonomy presented in the American Board of Internal Medicine’s (ABIM’s) Project Professionalism : altruism, accountability, excellence, duty, honour, integrity, and respect for others. 7 (From Ginsburg et al., The anatomy of a professional lapse [ 1 ])

In this passage, citation as referencing (in the form of Vancouver format superscript numbers) is used to acknowledge the source of knowledge. There are more than just references in this passage, however. Citation strategies also include statements that characterize the density of that knowledge (‘many reports’), its temporal patterns (‘continue to appear’), its diverse origins (‘both in the medical and education literature’), its social nature (‘often in reaction’), and its social import (‘important position statements’). Citation does more than just acknowledge the source of something you’ve read. It is how you represent the social nature of knowledge as coming from somewhere, being debated and developed, and having impact on the world [ 2 ]. If we remove all these citation strategies, the passage sounds at best like common sense or, at worst, like unsubstantiated personal opinion:

Despite years of effort to teach and enforce positive professional norms and standards, challenges to medical professionalism continue. Examples of professional lapses dot the health care landscape: regulations are thwarted, records are falsified, patients are ignored, colleagues are berated. Professionalism is a set of principles and values: altruism, accountability, excellence, duty, honour, integrity, and respect for others.

But perhaps you’ve been told that your literature review should be ‘objective’—that you should simply present what is known without taking a stance on it. This is largely untrue, for two reasons. The first involves the distinction between summary and critical summary. A summary is a neutral description of material, but a good literature review contains very little pure summary because, as we review, we must also judge the quality, source and reliability of the knowledge claims we are presenting [ 3 ]. To do this, we engage in critical summary, not only summarizing existing knowledge but offering a stance on it.

The second reason is that, even when we’re aiming for simple summary, a completely neutral presentation of knowledge claims is very difficult to achieve. We take a stance in ways we hardly even notice. Consider how the verb in each of these statements adds a flavour of stance to what is otherwise a summary of a knowledge claim in the field:

Anderson describes how the assessment is overly time-consuming for use in the Emergency Department. Anderson discovered that the assessment was overly time-consuming for use in the Emergency Department. Anderson claims that the assessment is overly time-consuming for use in the Emergency Department.

The first verb, ‘describes’, is neutral: it is not possible to ascertain the writer’s stance on the knowledge Anderson has contributed to the field. The second verb, ‘discovered’, expresses an affiliation or positive stance in the writer, while the third verb, ‘claims’, distances the writer from Anderson’s work. Even these brief summary sentences contain a flavour of critical summary. This is not a flaw; in fact, it is an important method of portraying existing knowledge as a conversation in which the writer is positioning herself and her work. But it should be done consciously and strategically. Tab. 1 offers examples to help writers think about how the verbs in their literature review position them in relation to existing knowledge in the field. Meaning is subject to context and these examples should only be taken as a guide: e. g., ‘suggests’ can be used to signal neutrality or distancing.

Verbs to position the writer in relation to the literature being reviewed

| Neutral about the knowledge | Affiliating with the knowledge | Distancing from the knowledge | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| comments explains indicates notes describes | observes remarks states finds | discovers reveals realizes understands | addresses argues recognizes identifies | assumes claims contends argues | hopes believes |

Most of us have favourite verbs that we default to almost unconsciously when we are writing—reports, argues, describes, studies, explains, asserts—but these verbs are not interchangeable. They each inscribe a slightly different stance towards the knowledge—not only the writer’s stance, but also the stance of the researcher who created the knowledge. It is critical to get the original stance right in your critical summary. Nothing irritates me more than seeing my stance mispresented in someone else’s literature review. For example, if I wrote a paragraph offering tentative reflections on a new idea, I don’t want to see that summarized in someone’s literature review as ‘Lingard argues’, when more accurate would be ‘Lingard suggests’ or ‘Lingard explored’.

Writers need to extend their library of citation verbs to allow themselves to accurately and persuasively position knowledge claims published by authors in their field. You can find many online resources to help extend your vocabulary: Tab. 2 , adapted from one such online source [ 4 ], provides some suggestions. Tables like these should be thought of as tools, not rules—keep in mind that words have flexible meanings depending on context and purpose. This is why one word, such as suggest or conclude , can appear in more than one list.

Verbs to represent the nature and strength of an author’s contributions to the literature

| Verbs to report what an author DID | Verbs to report what an author SAID | Verbs to report an author’s OPINION | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| analyse, assess, , discover, describe, demonstrate, examine, explore, establish, find, identify, inquire, prove, observe, study, show | Weaker | Stronger | Weaker | Stronger |

| comment, describe, note, remark, add, offer, | affirm, emphasize, stress, maintain, stipulate, explain, , identify, insist | accept, believe, consider, think, , suspect, speculate | argue, assert, claim, contend, deny, recommend, reject, advocate, maintain | |

Knowledge is a social construction and it accumulates as researchers debate, extend and refine one another’s contributions. To avoid your literature review reading like a laundry list of disconnected ‘facts’, reporting verbs are an important resource. Tab. 3 offers a selection of verbs organized to reflect different relationships among authors in the field of knowledge being reviewed.

Verbs to express relations among authors in the field

| Depicting similar positions | Depicting contrasting positions | Depicting relating/responding positions |

|---|---|---|

| Taylor Jackson’s claim that … | Taylor Jackson’s claim that … | Taylor to Jackson’s claim that … |

| affirms, agrees, confirms, concurs, aligns, shares, echoes, supports, verifies, concedes, accepts | argues, disagrees, questions, dismisses, refuses, rejects, challenges contradicts, criticizes, opposes, counters, disputes | extends, elaborates, refines, builds on, reconsiders, draws upon, advances, repositions, addresses |

Finally, although we have focused on citation verbs in this article, adverbs (e. g., similarly, consequently) and prepositional phrases (e. g., by contrast, in addition) are also important for expressing similar, contrasting or responding relations among knowledge claims and their authors in the field being reviewed.

In summary, an effective literature review not only summarizes existing knowledge, it also critically presents that knowledge to depict an evolving conversation and understanding in a particular domain of study. As writers we need to know when we are summarizing and when we are critically summarizing—summary alone makes for a literature review that reads like a laundry list of undigested ‘facts-in-the-world’. Finally, writers need to attend to the subtle power of citation verbs to position themselves and the authors they are citing in relation to the knowledge being reviewed. Broadening our catalogue of ‘go-to’ verbs is an important step in enlivening and strengthening our writing.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Mark Goldszmidt for his feedback on an early version of this manuscript.

PhD, is director of the Centre for Education Research & Innovation at Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry, and professor for the Department of Medicine at Western University in London, Ontario, Canada.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Action Verbs | Definition, List & Examples

Published on September 18, 2023 by Kassiani Nikolopoulou .

An action verb (also called a dynamic verb ) describes the action that the subject of the sentence performs (e.g., “I run”).

Action verbs differ from stative verbs, which describe a state of being (e.g., “believe,” “want”).

My grandfather walks with a stick.

The train arrived on time.

You can download our list of common action verbs in the format of your choice below.

Download PDF list Download Google Docs list

Table of contents

What is an action verb, how to use action verbs, action verbs vs. stative verbs, action verbs vs. linking verbs, worksheet: action verbs, other interesting language articles, frequently asked questions.

An action verb is a type of verb that describes the action that the subject of a sentence is performing. Action verbs can refer to both physical and mental actions (i.e., internal processes and actions related to thinking, perceiving, or feeling).

Whitney analyzed the data to find patterns.

He played football in high school.

Check for common mistakes

Use the best grammar checker available to check for common mistakes in your text.

Fix mistakes for free

Action verbs can be transitive or intransitive. Transitive verbs require a direct object , such as a noun or pronoun , that receives the action. Without a direct object, sentences with a transitive verb are vague or incomplete.

In contrast, intransitive verbs do not require a direct object that receives the action of the verb. However, other information may come after the verb, such as an adverb .

Some action verbs can act as both transitive and intransitive verbs.

He grows tomatoes on his balcony. My niece is growing quickly. Note Because action verbs make your writing more vivid, they can be effectively used for resume writing. Unlike generic phrases like “responsible for,” “tasked with,” or “experienced in,” action verbs are attention-grabbing and help emphasize our abilities and accomplishments.

- I was responsible for social media accounts across various platforms.

- I managed social media accounts across various platforms.

Action or dynamic verbs are often contrasted with stative verbs . While action verbs communicate action, stative verbs describe a state of being or perception (e.g., “it tasted,” “he is,” “she heard”). Due to this, they are typically used to provide more information about the subject, rather than express an action that the subject did. For example, the sentence “Tom loves spending time with friends” uses a stative verb “love” to give us more information about Tom’s personality.

However, some verbs can be used as either dynamic or stative verbs depending on the meaning of the sentence. For example, the verb “think” can denote someone’s opinion ( stative verb ) or the internal process of considering something ( action verb ).

One way to tell action verbs from stative verbs is to look at the verb tenses . Because stative verbs usually describe a state of being that is unchanging, they can’t be used in the continuous (or progressive) tenses. Action verbs, on the other hand, can be used in continuous tenses.

- I am wanting some food.

- I want some food.

Another way is to look at the meaning of the sentence and ask yourself if the verb shows what someone does or how someone feels or is. If the verb describes what someone does, it is an action verb. Otherwise, it is probably a stative verb.

Action verbs should not be confused with linking verbs , like “be,” “become,” and “seem.” Linking verbs connect the subject of a sentence with a subject complement (i.e., a noun or adjective that describes it).

Unlike action verbs, linking verbs do not describe an action, but add more details about the subject, such as how it looks or tastes.

For example, the sentence “The children seem happy” uses the linking verb “seem” to link the subject (“the children”) with the adjective (“happy”).

Some verbs can be either linking verbs or action verbs . If you are unsure, try replacing the linking verb with a conjugated form of the verb “be.” If the sentence still makes sense, then it is a linking verb.

To test your understanding of action verbs, try the worksheet below. Choose the correct answer for each question.

- Practice questions

- Answers and explanations

- Are you baking cookies? They_______[smell/are smelling] delicious!

- Understand is not an action verb, but a stative verb because we can’t use it in a continuous tense. For example, “I’m not understanding you at all” is incorrect.

- Kick is an action verb, while “believe” and “agree” are both stative verbs.

- Smell is correct because it is a stative verb and cannot be used in the present continuous.

If you want to know more about commonly confused words, definitions, common mistakes, and differences between US and UK spellings, make sure to check out some of our other language articles with explanations, examples, and quizzes.

Nouns & pronouns

- Common nouns

- Proper nouns

- Collective nouns

- Personal pronouns

- Uncountable and countable nouns

- Verb tenses

- Phrasal verbs

- Sentence structure

- Active vs passive voice

- Subject-verb agreement

- Interjections

- Determiners

- Prepositions

There are many ways to categorize verbs into various types. A verb can fall into one or more of these categories depending on how it is used.

Some of the main types of verbs are:

- Regular verbs

- Irregular verbs

- Transitive verbs

- Intransitive verbs

- Dynamic verbs

- Stative verbs

- Linking verbs

- Auxiliary verbs

- Modal verbs

If you are unsure whether a word is an action verb , consider whether it is describing an action (e.g., “run”) or a state of being (e.g., “understand”). If the word describes an action, then it’s an action verb.

The function of an action verb is to describe what the subject of the sentence is doing. For example, in the sentence “You have been working since 7 o’clock this morning,” the action verb “work” shows us what the subject (“you”) has been doing.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Nikolopoulou, K. (2023, September 18). Action Verbs | Definition, List & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved September 12, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/verbs/action-verb/

Is this article helpful?

Kassiani Nikolopoulou

Other students also liked, what is a transitive verb | examples, definition & quiz, what is an intransitive verb | examples, definition & quiz, what is a linking verb | definition & examples, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

100+ Research Vocabulary Words & Phrases

The academic community can be conservative when it comes to enforcing academic writing style , but your writing shouldn’t be so boring that people lose interest midway through the first paragraph! Given that competition is at an all-time high for academics looking to publish their papers, we know you must be anxious about what you can do to improve your publishing odds.

To be sure, your research must be sound, your paper must be structured logically, and the different manuscript sections must contain the appropriate information. But your research must also be clearly explained. Clarity obviously depends on the correct use of English, and there are many common mistakes that you should watch out for, for example when it comes to articles , prepositions , word choice , and even punctuation . But even if you are on top of your grammar and sentence structure, you can still make your writing more compelling (or more boring) by using powerful verbs and phrases (vs the same weaker ones over and over). So, how do you go about achieving the latter?

Below are a few ways to breathe life into your writing.

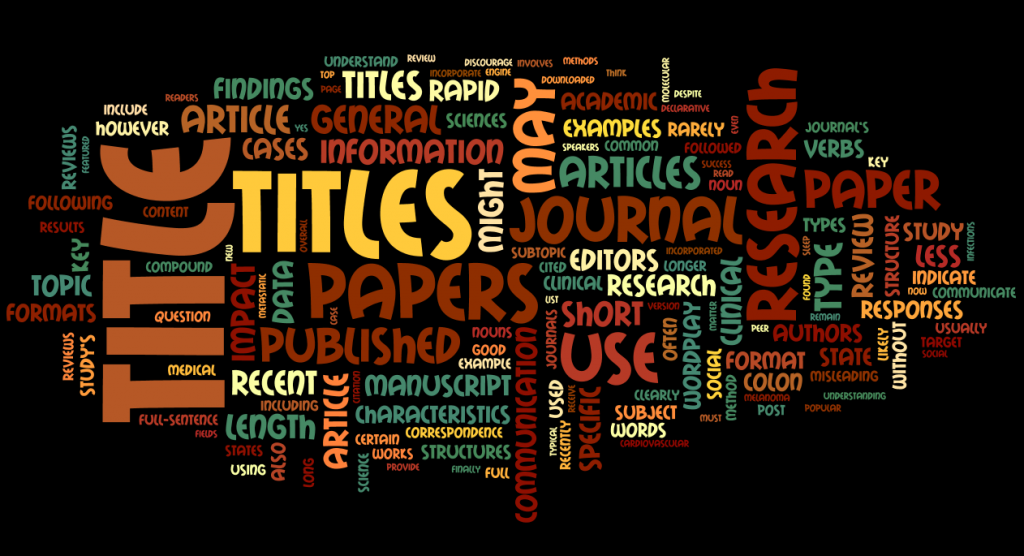

1. Analyze Vocabulary Using Word Clouds

Have you heard of “Wordles”? A Wordle is a visual representation of words, with the size of each word being proportional to the number of times it appears in the text it is based on. The original company website seems to have gone out of business, but there are a number of free word cloud generation sites that allow you to copy and paste your draft manuscript into a text box to quickly discover how repetitive your writing is and which verbs you might want to replace to improve your manuscript.

Seeing a visual word cloud of your work might also help you assess the key themes and points readers will glean from your paper. If the Wordle result displays words you hadn’t intended to emphasize, then that’s a sign you should revise your paper to make sure readers will focus on the right information.

As an example, below is a Wordle of our article entitled, “ How to Choose the Best title for Your Journal Manuscript .” You can see how frequently certain terms appear in that post, based on the font size of the text. The keywords, “titles,” “journal,” “research,” and “papers,” were all the intended focus of our blog post.

2. Study Language Patterns of Similarly Published Works

Study the language pattern found in the most downloaded and cited articles published by your target journal. Understanding the journal’s editorial preferences will help you write in a style that appeals to the publication’s readership.

Another way to analyze the language of a target journal’s papers is to use Wordle (see above). If you copy and paste the text of an article related to your research topic into the applet, you can discover the common phrases and terms the paper’s authors used.

For example, if you were writing a paper on links between smoking and cancer , you might look for a recent review on the topic, preferably published by your target journal. Copy and paste the text into Wordle and examine the key phrases to see if you’ve included similar wording in your own draft. The Wordle result might look like the following, based on the example linked above.

If you are not sure yet where to publish and just want some generally good examples of descriptive verbs, analytical verbs, and reporting verbs that are commonly used in academic writing, then have a look at this list of useful phrases for research papers .

3. Use More Active and Precise Verbs

Have you heard of synonyms? Of course you have. But have you looked beyond single-word replacements and rephrased entire clauses with stronger, more vivid ones? You’ll find this task is easier to do if you use the active voice more often than the passive voice . Even if you keep your original sentence structure, you can eliminate weak verbs like “be” from your draft and choose more vivid and precise action verbs. As always, however, be careful about using only a thesaurus to identify synonyms. Make sure the substitutes fit the context in which you need a more interesting or “perfect” word. Online dictionaries such as the Merriam-Webster and the Cambridge Dictionary are good sources to check entire phrases in context in case you are unsure whether a synonym is a good match for a word you want to replace.

To help you build a strong arsenal of commonly used phrases in academic papers, we’ve compiled a list of synonyms you might want to consider when drafting or editing your research paper . While we do not suggest that the phrases in the “Original Word/Phrase” column should be completely avoided, we do recommend interspersing these with the more dynamic terms found under “Recommended Substitutes.”

A. Describing the scope of a current project or prior research

To express the purpose of a paper or research | This paper + [use the verb that originally followed “aims to”] or This paper + (any other verb listed above as a substitute for “explain”) + who/what/when/where/how X. For example: | |

| To introduce the topic of a project or paper | ||

| To describe the analytical scope of a paper or study | *Adjectives to describe degree can include: briefly, thoroughly, adequately, sufficiently, inadequately, insufficiently, only partially, partially, etc. | |

| To preview other sections of a paper | [any of the verbs suggested as replacements for “explain,” “analyze,” and “consider” above] |

B. Outlining a topic’s background

| To discuss the historical significance of a topic | Topic significantly/considerably + + who/what/when/where/how…

*In other words, take the nominalized verb and make it the main verb of the sentence. | |

| To describe the historical popularity of a topic |

| verb] verb] |

| To describe the recent focus on a topic | ||

| To identify the current majority opinion about a topic | ||

| To discuss the findings of existing literature | ||

| To express the breadth of our current knowledge-base, including gaps | ||

| To segue into expressing your research question |

C. Describing the analytical elements of a paper

| To express agreement between one finding and another | ||

| To present contradictory findings | ||

| To discuss limitations of a study |

D. Discussing results

| To draw inferences from results | ||

| To describe observations |

E. Discussing methods

| To discuss methods | ||

| To describe simulations | This study/ research… + “X environment/ condition to..” + [any of the verbs suggested as replacements for “analyze” above] |

F. Explaining the impact of new research

| To explain the impact of a paper’s findings | ||

| To highlight a paper’s conclusion | ||

| To explain how research contributes to the existing knowledge-base |

Wordvice Writing Resources

For additional information on how to tighten your sentences (e.g., eliminate wordiness and use active voice to greater effect), you can try Wordvice’s FREE APA Citation Generator and learn more about how to proofread and edit your paper to ensure your work is free of errors.

Before submitting your manuscript to academic journals, be sure to use our free AI Proofreader to catch errors in grammar, spelling, and mechanics. And use our English editing services from Wordvice, including academic editing services , cover letter editing , manuscript editing , and research paper editing services to make sure your work is up to a high academic level.

We also have a collection of other useful articles for you, for example on how to strengthen your writing style , how to avoid fillers to write more powerful sentences , and how to eliminate prepositions and avoid nominalizations . Additionally, get advice on all the other important aspects of writing a research paper on our academic resources pages .

17 strong academic phrases to write your literature review (+ real examples)

A well-written academic literature review not only builds upon existing knowledge and publications but also involves critical reflection, comparison, contrast, and identifying research gaps. The following 17 strong academic key phrases can assist you in writing a critical and reflective literature review.

Academic key phrases to present existing knowledge in a literature review

The topic has received significant interest within the wider literature..

Example: “ The topic of big data and its integration with AI has received significant interest within the wider literature .” ( Dwivedi et al. 2021, p. 4 )

The topic gained considerable attention in the academic literature in…

Studies have identified….

Example: “ Studies have identified the complexities of implementing AI based systems within government and the public sector .” ( Dwivedi et al. 2021, p. 6 )

Researchers have discussed…

Recent work demonstrated that….

Example: “Recent work demonstrated that dune grasses with similar morphological traits can build contrasting landscapes due to differences in their spatial shoot organization.” ( Van de Ven, 2022 et al., p. 1339 )

Existing research frequently attributes…

Prior research has hypothesized that…, prior studies have found that….

Example: “ Prior studies have found that court-referred individuals are more likely to complete relationship violence intervention programs (RVIP) than self-referred individuals. ” ( Evans et al. 2022, p. 1 )

Academic key phrases to contrast and compare findings in a literature review

While some scholars…, others…, the findings of scholar a showcase that… . scholar b , on the other hand, found….

Example: “ The findings of Arinto (2016) call for administrators concerning the design of faculty development programs, provision of faculty support, and strategic planning for online distance learning implementation across the institution. Francisco and Nuqui (2020) on the other hand found that the new normal leadership is an adaptive one while staying strong on their commitment. ” ( Asio and Bayucca, 2021, p. 20 )

Interestingly, all the arguments refer to…

This argument is similar to….

If you are looking to elevate your writing and editing skills, I highly recommend enrolling in the course “ Good with Words: Writing and Editing Specialization “, which is a 4 course series offered by the University of Michigan. This comprehensive program is conveniently available as an online course on Coursera, allowing you to learn at your own pace. Plus, upon successful completion, you’ll have the opportunity to earn a valuable certificate to showcase your newfound expertise!

Academic key phrases to highlight research gaps in a literature review

Yet, it remains unknown how…, there is, however, still little research on…, existing studies have failed to address….

Example: “ University–industry relations (UIR) are usually analysed by the knowledge transfer channels, but existing studies have failed to address what knowledge content is being transferred – impacting the technology output aimed by the partnership.” (Dalmarco et al. 2019, p. 1314 )

Several scholars have recommended to move away…

New approaches are needed to address…, master academia, get new content delivered directly to your inbox, 26 powerful academic phrases to write your introduction (+ real examples), 13 awesome academic phrases to write your methodology (+ real examples), related articles, 10 tips on how to use reference management software smartly and efficiently, separating your self-worth from your phd work, how to introduce yourself in a conference presentation (in six simple steps), how to write effective cover letters for a paper submission.

- Generating Ideas

- Drafting and Revision

- Sources and Evidence

- Style and Grammar

- Specific to Creative Arts

- Specific to Humanities

- Specific to Sciences

- Specific to Social Sciences

- CVs, Résumés and Cover Letters

- Graduate School Applications

- Other Resources

- Hiatt Career Center

- University Writing Center

- Classroom Materials

- Course and Assignment Design

- UWP Instructor Resources

- Writing Intensive Requirement

- Criteria and Learning Goals

- Course Application for Instructors

- What to Know about UWS

- Teaching Resources for WI

- FAQ for Instructors

- FAQ for Students

- Journals on Writing Research and Pedagogy

- University Writing Program

- Degree Programs

- Graduate Programs

- Brandeis Online

- Summer Programs

- Undergraduate Admissions

- Graduate Admissions

- Financial Aid

- Summer School

- Centers and Institutes

- Funding Resources

- Housing/Community Living

- Clubs and Organizations

- Community Service

- Brandeis Arts Engagement

- Rose Art Museum

- Our Jewish Roots

- Mission and Diversity Statements

- Administration

- Faculty & Staff

- Alumni & Friends

- Parents & Families

- Campus Calendar

- Directories

- New Students

- Shuttle Schedules

- Support at Brandeis

Writing Resources

Active verbs for discussing ideas.

This handout is available for download in PDF format .

Active verbs are important components of any academic writing! Just as in other forms of writing, they work as engines, driving the action of your sentences in many potentially vivid, clear, and colorful ways.

Instead of opting for bland, unspecific expressions ("says," "writes about," "believes," "states") consider using more vivid or nuanced verbs such as "argues," "insists," "explains," "emphasizes," "challenges," "agrees," etc. The list below offers dozens of such verbs that will help you communicate your ideas and the ideas of others more clearly, expressively, and powerfully.

| Action Verbs A-C | Action Verbs D-H | Action Verbs I-Q | Action Verbs R-Z |

|---|---|---|---|

| accepts | declares | identifies | ratifies |

| acknowledges | defends | illuminates | rationalizes |

| adds | defies | implies | reads |

| admires | demands | infers | reconciles |

| affirms | denies | informs | reconsiders |

| allows that | describes | initiates | refutes |

| analyzes | determines | insinuates | regards |

| announces | diminishes | insists | rejects |

| answers | disagrees | interprets | relinquishes |

| argues | discusses | intimates | reminds |

| assaults | disputes | judges | repudiates |

| assembles | disregards | lists | resolves |

| asserts | distinguishes | maintains | responds |

| assists | emphasizes | marshals | retorts |

| buttresses | endorses | narrates | reveals |

| categorizes | enumerates | negates | reviews |

| cautions | exaggerates | observes | seeks |

| challenges | experiences | outlines | sees |

| claims | experiments | parses | shares |

| clarifies | explains | perceives | shifts |

| compares | exposes | persists | shows |

| complicates | facilitates | persuades | simplifies |

| concludes | formulates | pleads | states |

| condemns | grants | points out | stresses |

| confirms | guides | postulates | substitutes |

| conflates | handles | praises | suggests |

| confronts | hesitates | proposes | summarizes |

| confuses | highlights | protects | supplements |

| considers | hints | provides | supplies |

| contradicts | hypothesizes | qualifies | supports |

| contrasts | synthesizes | ||

| convinces | tests | ||

| criticizes | toys with | ||

| critiques | treats | ||

| uncovers | |||

| undermines | |||

| urges | |||

| verifies | |||

| warns |

- "mentions," unless you mean "refer to something briefly and without going into detail."*

- "notion" as a synonym for "idea" implies "impulsive," "whimsical," not well considered.*

Adapted from a list by Cinthia Gannett by Doug Kirshen and Robert B. Cochran, Brandeis University Writing Program, 2020.

- Resources for Students

- Writing Intensive Instructor Resources

- Research and Pedagogy

The Significance of Research Verbs: Elevating Academic Writing

Want to master the art of writing? Start with research verbs! Learn how to make your writing more informative & interesting with our guide.

Despite their unassuming looks, research verbs carry substantial weight in academic writing. The building blocks of argument development, method explanation, and evidence presentation are research verbs. Researchers can communicate their findings clearly and demonstrate the rigor and trustworthiness of their research by choosing the appropriate research verbs. Furthermore, by clarifying the author’s thought process and assisting in comprehension, these verbs can aid readers in navigating the complexity of academic literature.

Although they are of remarkable significance, research verbs are frequently misused, despite the fact that they are extremely important in determining the impact and clarity of academic writing. This article by Mind the Graph explores the essential significance of using the right research verbs to improve the quality and effectiveness of academic discourse.

What are Research Verbs?

Research verbs are a specific and essential category of words utilized in academic writing to convey the actions, procedures, and findings of research. They play a significant role in enhancing the clarity, precision, and effectiveness of researchers’ writing, enabling them to express their intentions with greater impact.

Within academic writing, research verbs cover a broad spectrum of actions and concepts associated with research. They encompass verbs used to describe research methods (e.g., investigate, analyze, experiment), present research findings (e.g., demonstrate, reveal, illustrate), and discuss implications and conclusions (e.g., suggest, propose, validate).

The careful selection of research verbs holds utmost importance as it directly influences the overall tone, rigor, and credibility of academic writing. By choosing the most fitting research verbs, researchers can ensure their writing is precise, clear, and accurate, allowing them to effectively communicate their research to their intended audience.

In addition to research verbs, selecting the right words throughout the academic writing process is crucial. It contributes to the attainment of the aforementioned goals of precision, clarity, and accuracy. To gain deeper insights into the importance of word choice in academic writing, read the article titled “ The Importance of Word Choice with Examples. ” This article offers valuable perspectives and practical examples that can further enhance your understanding of the significance of word choice in academic writing.

Types of Research Verbs

There are various types of research verbs that are commonly used in academic writing. These verbs can be categorized based on their specific functions and the stages of the research process they represent.

Verbs for Analyzing Data

To examine, understand, and gain significant insights from research findings, particular verbs are used when analyzing data. These verbs aid in the exploration of connections, the discovery of patterns, and the drawing of conclusions based on the available facts:

- Analyze: Systematically examine data to find patterns or connections.

- Interpret: Describe the relevance of the data or outcomes and their meaning.

- Compare: Show how several data sets or variables differ from one another.

- Correlate: Examine the connection or relationship between variables.

- Calculate: Perform calculations on data using math or statistics.

Verbs for Defining Processes

Defining research processes entails providing specifics on the steps, procedures, and methods used throughout the study. Verbs in this category facilitate a clear and accurate explanation of how the research was conducted:

- Outline: Provide a general overview or structure of a research process.

- Detail: Elaborate on the specific steps or procedures undertaken in the research.

- Explain: Clarify the rationale or logic behind a particular research process.

- Define: Clearly state and describe key concepts, variables, or terms.

- Illustrate: Use examples or visuals to demonstrate a research process.

Verbs for Summarizing Results

After the research has been concluded, researchers provide a succinct summary of their results. These verbs help researchers highlight key findings, give an overview of the findings, and draw conclusions from the data:

- Summarize: Provide a concise overview or brief account of research findings.

- Highlight: Draw attention to the key or significant results.

- Demonstrate: Present evidence or data that supports a particular finding.

- Conclude: Formulate a generalization or inference based on the results.

- Validate: Confirm or corroborate the findings through additional evidence or analysis.

Verbs for Describing Literature Review

During the literature review phase, researchers examine existing scholarly works and relevant studies. Verbs in this category help researchers express their evaluation, synthesis, and analysis of the literature. Such verbs include, for instance:

- Critique: Evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of existing literature on a topic.

- Summarize: Provide a brief overview of the key findings and conclusions of existing literature on a topic.

- Compare: Identify similarities and differences between the findings and conclusions of multiple studies on a topic.

- Synthesize: Combine the findings and conclusions of multiple studies on a topic to identify broader trends or themes.

- Evaluate: Assess the quality and validity of existing literature on a topic.

Verbs for Speculating and Hypothesizing

Exploring possible connections or explaining occurrences requires speculation and the formulation of hypotheses. These verbs allow researchers to present their speculations, assumptions, or proposed hypothesis:

- Propose: Put forward an idea or hypothesis for further study or investigation.

- Speculate: Offer a possible explanation or theory for a phenomenon or observation.

- Predict: Use existing data or theories to make a forecast about future events or outcomes.

- Hypothesize: Formulate a testable explanation or hypothesis for a phenomenon or observation.

- Suggest: Offer a potential explanation or interpretation for a result or finding.

Verbs for Discussing Limitations and Future Directions

Acknowledging the limitations of the research and suggesting future directions is important for demonstrating a comprehensive understanding of the field. Verbs in this category help researchers address the constraints of their study and provide insights for future research:

- Limit: Identify the limitations or weaknesses of a study or analysis.

- Propose: Suggest potential solutions or avenues for further research to address limitations or weaknesses.

- Discuss: Analyze and reflect on the implications of limitations or weaknesses for the broader field or research area.

- Address: Develop a plan or strategy for addressing limitations or weaknesses in future research.

- Acknowledge: Recognize and address potential biases or limitations in a study or analysis.

Tips for Using Research Verbs

These tips will help you make the most of research verbs, ensuring that your language is active, precise, and consistent. By incorporating these strategies, you can elevate the quality of your writing and effectively communicate your research findings to your readers.

Using Active Language

- Use active voice: Active voice makes your writing more dynamic and engaging. It also clearly identifies the doer of the action. For example, instead of saying “The data were analyzed,” say “We analyzed the data.”

- Highlight the subject: Ensure that the subject of the sentence is the main focus and performs the action. This brings clarity and emphasizes responsibility.

Choosing Precise Verbs

- Be specific: Select verbs that precisely convey the action you want to describe. Avoid generic verbs like “do” or “make.” Instead, use verbs that accurately depict the research process or findings. For example, use “investigate,” “analyze,” or “demonstrate.”

- Utilize a thesaurus: Expand your vocabulary and find alternative verbs that convey the exact meaning you intend. A thesaurus can help you discover more precise and varied verbs.

Maintaining Consistency

- Stay consistent in verb tense: Choose a verb tense and maintain it consistently throughout your writing. This ensures coherence and clarity.

- Establish a style guide: Follow a specific style guide, such as APA or MLA, to maintain consistency in the use of research verbs and other writing conventions.

Resources to Help You Use Research Verbs

Take into consideration the following resources to improve your use of research verbs:

- Writing Manuals and Guides: For reliable information on research verbs and academic writing, consult guides such as “The Craft of Research” or “The Elements of Style.”

- Academic Writing Workshops: Attend webinars or workshops on academic writing that address subjects like research verbs and enhancing scholarly writing.

- Online Writing Communities: Participate in online writing communities where researchers exchange materials and discuss writing techniques.

- Language and Writing Apps: Use grammar checker tools like Grammarly or ProWritingAid for grammar and style suggestions.

Exclusive scientific content, created by scientists

Mind the Graph provides exclusive scientific content created by scientists to support researchers in their scientific endeavors. The platform offers a comprehensive range of tools and resources, with a focus on scientific communication and visualization, Mind the Graph empowers researchers to effectively showcase their work, collaborate with peers, and stay up-to-date with the latest scientific trends.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Exclusive high quality content about effective visual communication in science.

Sign Up for Free

Try the best infographic maker and promote your research with scientifically-accurate beautiful figures

no credit card required

About Jessica Abbadia

Jessica Abbadia is a lawyer that has been working in Digital Marketing since 2020, improving organic performance for apps and websites in various regions through ASO and SEO. Currently developing scientific and intellectual knowledge for the community's benefit. Jessica is an animal rights activist who enjoys reading and drinking strong coffee.

Content tags

- Current Students

- News & Press

- Exam Technique for In-Person Exams

- Revising for 24 Hour Take Home Exams

- Introduction to 24 Hour Take Home Exams

- Before the 24 Hour Take Home Exam

- Exam Technique for 24 Hour Take Home Exams

- Structuring a Literature Review

- Writing Coursework under Time Constraints

- Reflective Writing

- Writing a Synopsis

- Structuring a Science Report

- Presentations

- How the University works out your degree award

- Accessing your assignment feedback via Canvas

- Inspera Digital Exams

- Writing Introductions and Conclusions

Paragraphing

- Reporting Verbs

Signposting

- Proofreading

- Working with a Proofreader

- Writing Concisely

- The 1-Hour Writing Challenge

- Editing strategies

- Apostrophes

- Semi-colons

- Run-on sentences

- How to Improve your Grammar (native English)

- How to Improve your Grammar (non-native English)

- Independent Learning for Online Study

- Reflective Practice

- Academic Reading

- Strategic Reading Framework

- Note-taking Strategies

- Note-taking in Lectures

- Making Notes from Reading

- Using Evidence to Support your Argument

- Integrating Scholarship

- Managing Time and Motivation

- Dealing with Procrastination

- How to Paraphrase

- Quote or Paraphrase?

- How to Quote

- Referencing

- Responsible and Ethical use of AI

- Acknowledging use of AI

- Numeracy, Maths & Statistics

- Library Search

- Search Techniques

- Keeping up to date

- Evaluating Information

- Managing Information

- Understanding Artificial Intelligence

- Getting started with prompts

- Thinking Critically about AI

- Using Information generated by AI

- SensusAccess

- Develop Your Digital Skills

- Digital Tools to Help You Study

Explore different ways of referring to literature and foregrounding your voice.

- Newcastle University

- Academic Skills Kit

- Academic Writing

Reporting verbs help you introduce the ideas or words of others as paraphrase or quotation from scholarly literature. Always accompanied by a reference, they indicate where you’re drawing on other people’s work to build your own argument. They also indicate your stance (agree, disagree, etc) on the scholarship you’re describing, highlighting your critical contribution. There are lots of reporting verbs to choose from and, depending on the context, they might be used to convey more than one stance, so you’ll notice that some appear in more than one category.

The following reporting verbs have been organised according to the critical stances they signal.

Neutral description of what the text says

Reporting verbs.

- Observes

- Describes

- Discusses

- Reports

- Outlines

- Remarks

- States

- Goes on to say that

- Quotes that

- Mentions

- Articulates

- Writes

- Relates

- Conveys

Abrams mentions that culture shock has “long been misunderstood as a primarily psychological phenomenon” (34)

Chakrabarty outlines the four stages of mitosis (72-3)

Acceptance as uncontested fact, having critiqued it

- Recognises

- Clarifies

- Acknowledges

- Concedes

- Accepts

- Refutes

- Uncovers

- Admits

- Demonstrates

- Highlights

- Illuminates

- Supports

- Concludes

- Elucidates

- Reveals

- Verifies

Abrams refutes the idea that culture shock is a “primarily psychological phenomenon” (34)

Chakrabarty demonstrates that mitosis actually occurs over five stages (73)