What is Fine Art? Learn About the Definition and the Different Types of Fine Art

This post may contain affiliate links. If you make a purchase, My Modern Met may earn an affiliate commission. Please read our disclosure for more info.

If you've ever taken an art course or visited a gallery, you've likely come across the term “fine art.” Though it may sound like this describes the quality or value of the art, it actually relates to the purity of the artistic pursuit. Unlike crafts or decorative works, fine art is created solely for aesthetic and intellectual purposes.

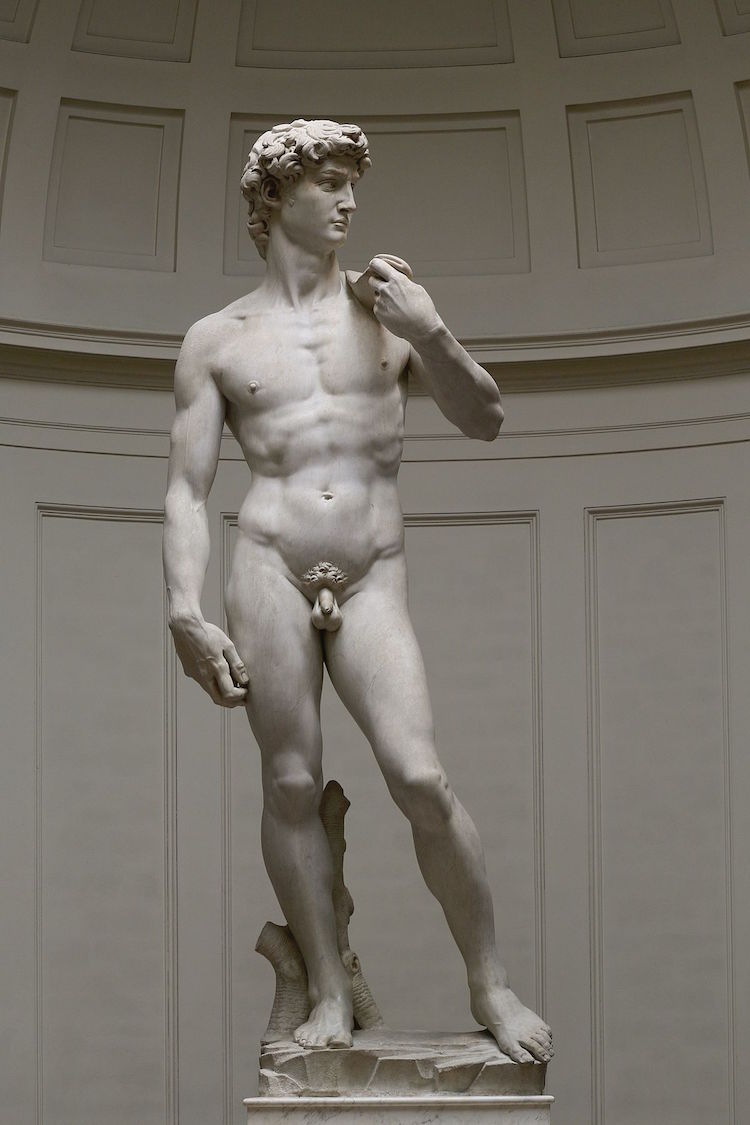

When thinking of examples of fine art, famous paintings like the Girl with a Pearl Earring or sculptures like Michelangelo's David usually come to mind. However, this phrase actually encompasses several different disciplines: painting, sculpture, drawing, installation, architecture, and fine art photography. And the list continues to develop.

Here we will learn about the different types of fine art and take a look at some examples.

What is Fine Art?

Théodore Géricault, “The Raft of The Medusa,” 1818–9 (Photo: Louvre via Wikimedia Commons , Public domain)

Fine art traditionally refers to types of art that primarily serve an aesthetic or intellectual purpose. This usually applies to visual arts, such as painting and sculpture, but has also been used to describe other creative disciplines including music, architecture, poetry, and performing arts. In this case, the use of the word “fine” refers to the integrity of the artistic pursuit.

The definition of fine art excludes arts that serve functional purposes, most notably crafts and applied arts.

Types of Fine Art

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, “Portrait of Victor Baltard's Wife (born Adeline Lequeu) and their Daughter Paule,” c. 1800s (Photo: Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons )

With a history tracing back to Paleolithic times, drawing is one of the oldest forms of human communication and creativity. It denotes the practice of making marks on two-dimensional surfaces like paper or board with the aid of a utensil, such as a pencil, pen, charcoal, etc.

Drawing is one of the fundamental elements of art, serving a variety of purposes for creatives. While it can be an art form in itself, it is also used by artists to explore ideas and concepts and to prepare for final artworks in another medium, like painting.

Édouard Manet, “A Bar at the Folies-Bergère,” 1882 (Photo: The Courtauld Institute of Art via Wikimedia Commons , Public domain)

Painting is perhaps the most well-known form of fine art that can be viewed in museums around the world. It describes the act of applying paint or pigment to a hard surface, usually through means of another device, such as a brush or palette knife.

Like drawing, painting has roots dating back thousands of years, making it another age-old form of human expression. Its evolution from cave decorations to depictions on canvas can be credited to developments in painting materials .

In Western art, painting has evolved through numerous art movements —using the medium to explore different aesthetics and ideas triggered by the historical context. Additionally, some of the most famous works of fine art are also paintings, including The Mona Lisa and The Starry Night .

Printmaking

Albrecht Dürer, “Melencolia I,” 1511 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons , Public domain)

Printmaking is a practice that transfers ink from a matrix onto material—typically paper—making multiple impressions of the same image. Matrixes can be made of different materials, including wood, metal plates, linoleum, aluminum, or fabric. While there are different printmaking techniques (each having its own distinct characteristics), the end result is the ability to make several impressions of a single image.

In modern times, prints are issued in editions. Each edition will have a limited number of impressions, though artists sometimes issue open editions. Once the edition is done being printed, the matrix is destroyed and every single impression is considered an original work of art. Traditionally, once printmaking took off, prints were also often used to illustrate books or were sold in small bound collections.

Michelangelo, “David,” 1501–1504 (Photo: Jörg Bittner Unna via Wikimedia Commons , CC BY-SA 3.0 )

A sculpture is a three-dimensional work of art created from an additive or subtractive process of the material. In this discipline, artists usually carve or assemble a form from stone, marble, wood, clay, metal, and ceramics, among other materials.

The practice of sculpture has existed for centuries. In fact, one of the oldest known works of art, titled The Venus of Willendorf , is a miniature statuette carved from limestone between 30,000 and 25,000 BCE. Western sculpture as we know it now, however, first blossomed in ancient Greece, when artists captured the human figure with anatomical realism. Since then, it has developed over the course of different art movements, encompassing a range of styles and approaches.

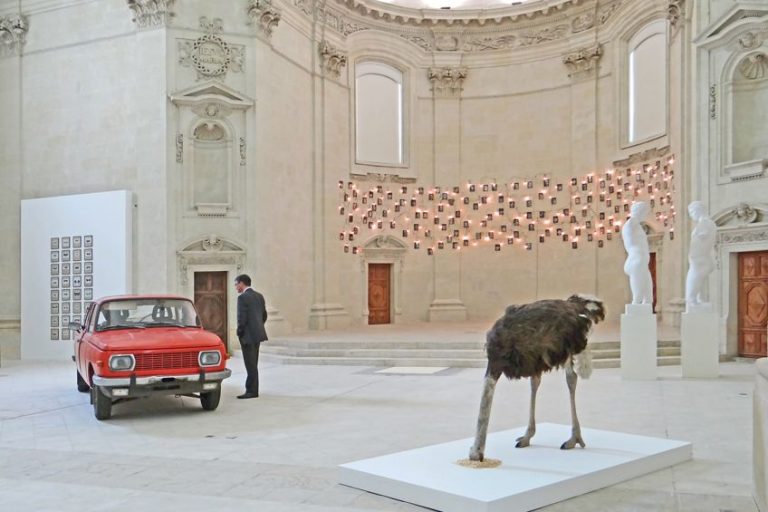

Installation

Robert Smithson, “Spiral Jetty,” 1970 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons , CC BY-SA 2.5 )

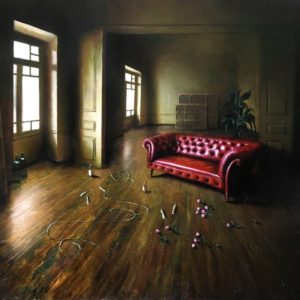

Installation art is a modern movement characterized by immersive, larger-than-life works of art. Usually, installation artists create these pieces for specific locations, enabling them to expertly transform any space into a customized, interactive environment.

Fine Art Photography

Alfred Stieglitz, “Old and New New York,” 1910 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons , Public domain)

Fine art photography runs contrary to what most of us think about when thinking about how we use a camera. Most amateur photographers use their cameras to document important events and capture memories without artistic motivation. Instead, a distinguishing feature of fine art photography is that recording a subject is not the main purpose. These artists use photography as a means to express their vision and make an artistic statement.

Examples of Famous Fine Art Paintings

Jan van eyck, the arnolfini portrait , 1434.

Jan Van Eyck, “The Arnolfini Portrait,” 1434 (Photo: National Gallery via Wikimedia Commons , Public domain)

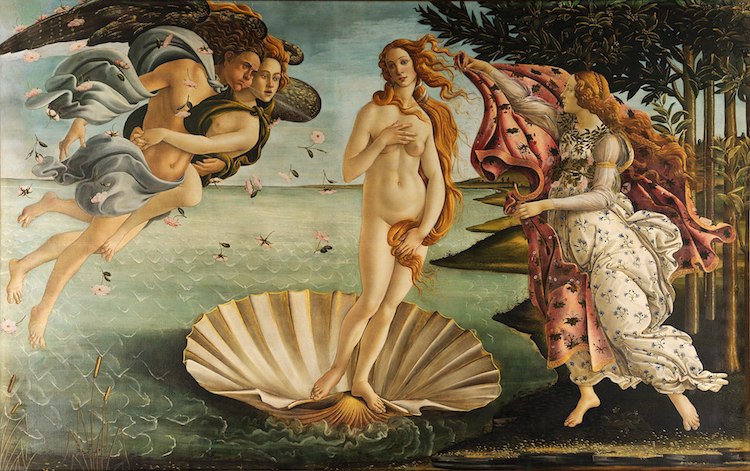

Sandro Botticelli, The Birth of Venus , c. 1484–6

Sandro Botticelli, “The Birth of Venus,” c. 1484–1486 (Photo: Uffizi via Wikimedia Commons , Public domain)

Leonardo da Vinci, The Mona Lisa , c. 1503–1506

Leonardo da Vinci, “The Mona Lisa,” c. 1503–1506 (Photo: Louvre via Wikimedia Commons , Public Domain)

Raphael, The School of Athens , 1509–1511

Raphael, “The School of Athens,” 1509–11 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons , Public domain)

Diego Velázquez, Las Meninas , 1656–7

Diego Velázquez, “Las Meninas,” 1656–1657 (Photo: Museo del Prado via Wikimedia Commons , Public domain)

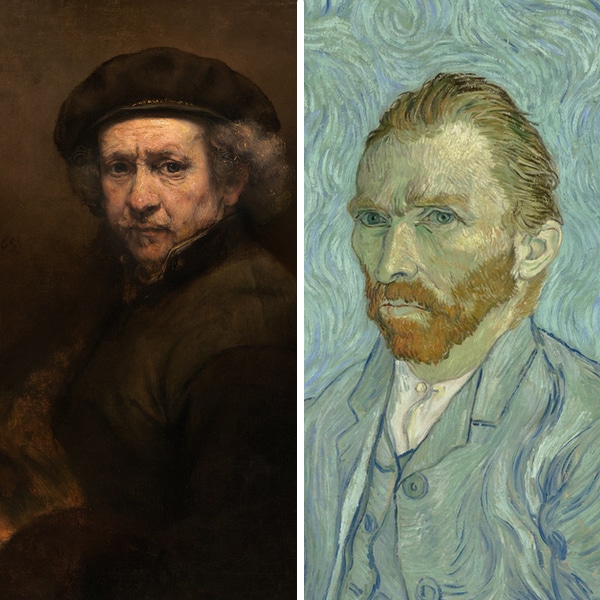

Rembrandt van Rijn, The Night Watch , 1642

Rembrandt, “The Nightwatch,” 1642 (Photo: Rijksmuseum via Wikimedia Commons , Public domain)

Johannes Vermeer, Girl With a Pearl Earring , c. 1665

Johannes Vermeer, “Girl with a Pearl Earring,” c. 1665 (Photo: Mauritshuis via Wikimedia Commons , Public domain)

Eugène Delacroix, Liberty Leading the People , 1830

Eugène Delacroix, “Liberty Leading the People,” 1830 (Photo: Louvre via Wikimedia Commons , Public domain)

Édouard Manet, Le Déjeuner sur l'Herbe , 1863

Édouard Manet, “Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe,” 1863 (Photo: Musée d'Orsay via Wikimedia Commons , Public domain)

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Bal du moulin de la Galette , 1876

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, “Bal du moulin de la Galette,” 1876 (Photo: Musée d'Orsay via Wikimedia Commons , Public domain)

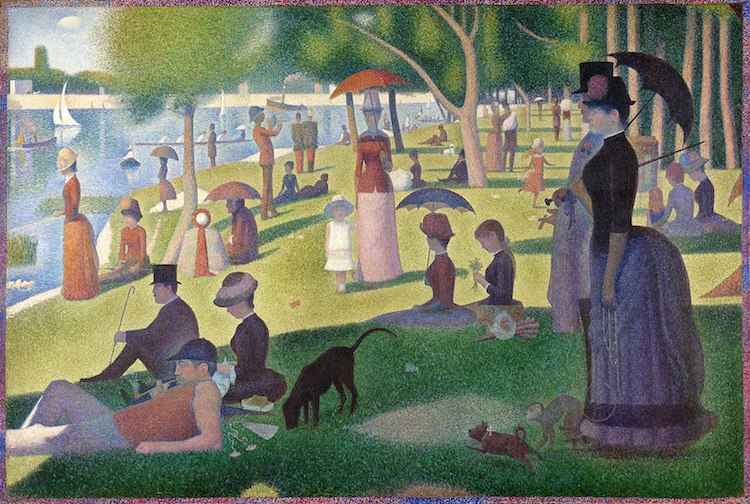

Georges Seurat, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte , 1884–6

Georges Seurat, “A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte,” 1884–6 (Photo: Art Institute of Chicago via Wikimedia Commons , Public domain)

Vincent van Gogh, The Starry Night , 1889

Vincent van Gogh , “The Starry Night ,” 1889 (Photo: MoMA via Wikimedia Commons , Public domain)

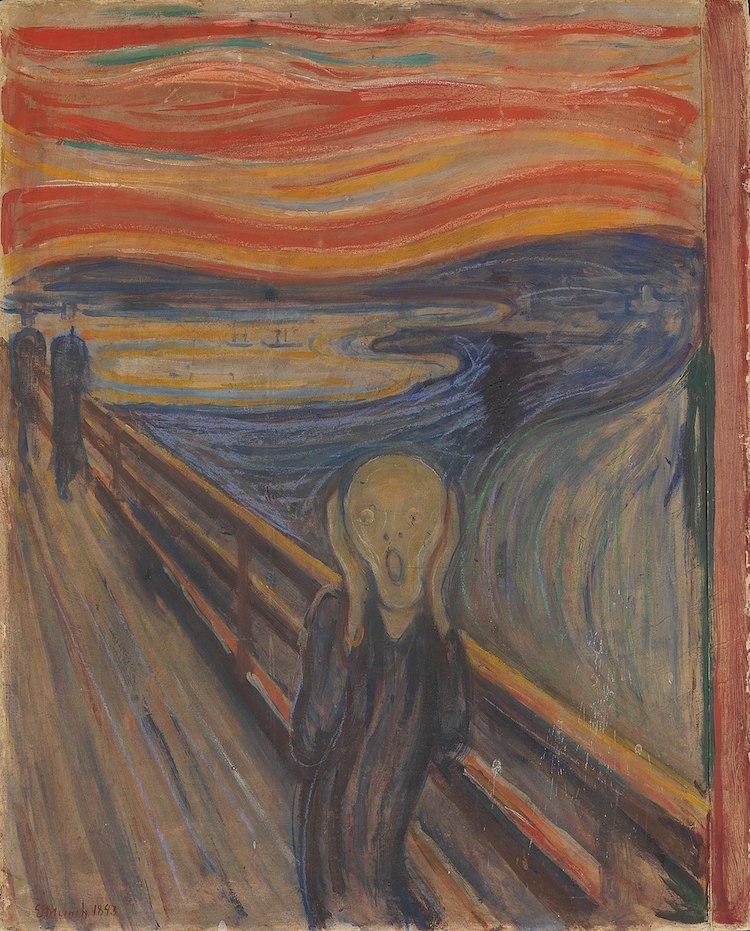

Edvard Munch, The Scream , 1893

Edvard Munch, “The Scream,” 1893 (Photo: National Gallery of Norway via Wikimedia Commons , Public domain)

Gustav Klimt, The Kiss , 1907–8

Gustav Klimt, “The Kiss,” oil and gold leaf on canvas, 1907–1908 (Photo: Belvedere via Wikimedia Commons , Public domain)

Pablo Picasso, Les Demoiselles d'Avignon , 1907

Pablo Picasso, “Les Demoiselles d'Avignon,” 1907 (Photo: MoMA via Wikimedia Commons , Fair use)

Salvador Dalí, The Persistence of Memory , 1931

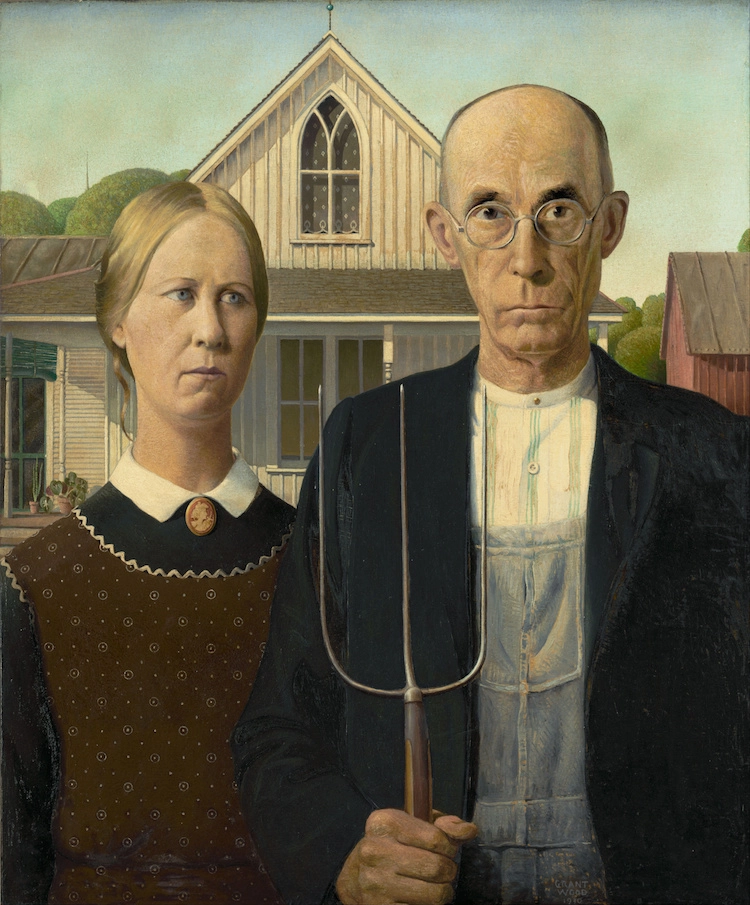

Grant Wood, American Gothic , 1930

Grant Wood, “American Gothic,” 1930 (Photo: Art Institute of Chicago via Wikimedia Commons , Public domain)

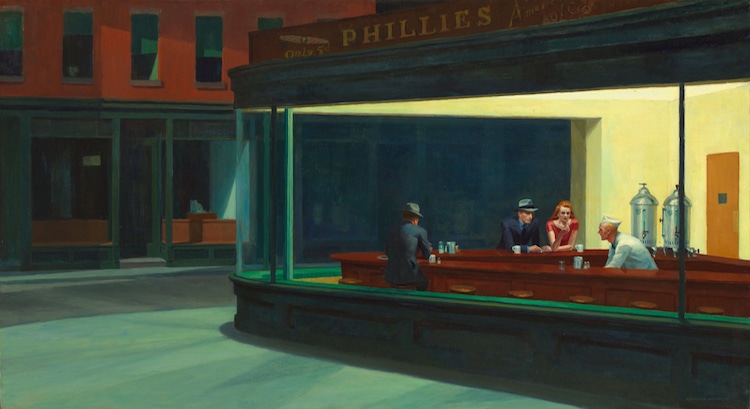

Edward Hopper, Nighthawks , 1942

Edward Hopper, “Nighthawks,” 1942 (Photo: Art Institute of Chicago via Wikipedia , Public domain)

Check out our full list of famous paintings .

Books about fine art, frequently asked questions, what is fine art, what arts are considered fine arts.

Today, fine arts is usually applied to visual arts like painting, drawing, sculpture, printmaking, installation, and fine art photography.

Related Articles:

13 of Art History’s Most Horrifying Masterpieces

Why Rembrandt Is Considered One of Art History’s Most Important Old Masters

30 Famous Paintings From Western Art History Any Art Lover Should Know

Set Sail on a Journey Through 9 of Art History’s Most Important Seascape Paintings

Get Our Weekly Newsletter

Learn from top artists.

Related Articles

Sponsored Content

More on my modern met.

My Modern Met

Celebrating creativity and promoting a positive culture by spotlighting the best sides of humanity—from the lighthearted and fun to the thought-provoking and enlightening.

- Photography

- Architecture

- Environment

Fine Art: Definition, History and Examples

In the realms of creativity and expression, various disciplines stand out, one of which is fine art. This form of art, steeped in history and culture, has evolved considerably over the centuries. This article delves into the definition of fine art, its evolution, the distinction between fine art, digital art, and craft. It also explores the range of mediums used in fine art, and the various art movements that have influenced it over time. Join us as we embark on this fascinating exploration of fine art—a remarkable testament to human creativity and imagination.

Fine Art Definition

Fine art is an expression of creativity and imagination that takes the form of visual works. It is created primarily for its aesthetic content, rather than practical or commercial purposes. Fine art is usually made to achieve a particular aesthetic, intellectual or emotional effect on the viewer. However, it can also be used as a means of communication. It is defined as being different from decorative arts and applied arts, as these focus on making practical objects more aesthetically pleasing. Fine art has been around for centuries, evolving in technique and style over this time.

How Has Fine Art Evolved?

The journey of fine art began with the earliest societies. They used visual expression as a means of communication and representation . Cave paintings, stone carvings, and sculptures from these early periods of human history are some of the first examples of art. These artworks served both aesthetic and functional purposes. They often depicted the daily life, religious beliefs, and societal structures of their creators.

The Ancient Greeks’ focus on humanism, observed in their sculptures and architecture, laid the foundation for Western art. Their pursuit of realism, coupled with their profound understanding of human anatomy and proportion, elevated art to a higher level of refinement. This spirit of humanistic and aesthetic exploration reached its pinnacle during the Renaissance .

The art of the High Renaissance , characterised by its astonishing realism, depth and perspective, is often considered a testament to the peak of artistic ability. The Renaissance also saw a distinct shift in the perception of the artist—from artisans as craftsmen to esteemed intellectuals.

The evolution of fine art accelerated with the introduction of the printing press in the 15th century. This then led to wider dissemination and scrutiny of artistic works. Over time, art moved from being predominantly representative to being more expressive and abstract. The 20th century, in particular, saw an explosion of non-representational art movements . These movements challenged traditional notions of aesthetics and meaning in art.

The shifts in style and subject that we see in each art movement were influenced by various factors, including socioeconomic conditions, patrons’ preferences, religious beliefs, and mythical narratives. The evolution of fine art continues to this day, shaped by technology, globalisation, and a constantly changing world.

What is the Purpose of Fine Art?

Fine art serves multiple purposes, both for the individual artist and society as a whole. One of its most significant roles is the preservation of our transient existence—an idea beautifully embodied in the ancient handprints found on cave walls. These prehistoric imprints are a potent reminder that our ancestors sought to leave a lasting trace of their existence. This desire for individual legacy continues to inspire artists today.

Art documents the course of human history

Beyond personal legacy, fine art also serves as a powerful tool for documenting history. Artists often reflect and respond to the societal and cultural shifts of their time. There works, therefore serve as visual records of historical events, societal norms, philosophical ideologies, and cultural trends. For instance, the dramatic changes in art styles throughout history often mirror the tumultuous societal upheavals of the times, from the religious turmoil of the Reformation to the political instability of the French Revolution.

Art is an importance means for expression

Fine art is a powerful medium for expressing perspectives, intellectual ideas, and a spectrum of human emotions. Whether it’s a haunting portrait that captures the human condition or an abstract piece that challenges conventional thought, each work of art encourages viewers to contemplate, empathise, or question, thereby broadening their understanding of the world around them.

Lastly, one cannot overlook the aesthetic purpose of fine art. Artists strive to create works that are visually pleasing or intriguing, using a variety of techniques to manipulate line, colour, shape, and texture to achieve desired effects. This aspect of fine art, despite its subjectivity, is often what draws viewers in, inviting them to appreciate the inherent beauty and complexity of the artwork, whether it’s the mesmerising brush strokes of an Impressionist painting or the striking simplicity of a minimalist sculpture.

Nowadays there is a large collector’s market for fine art. The value of art can be seen in its monetary value. Historically significant pieces and pieces by famous artists are often sold to buyers for hundreds of thousands, sometimes even millions of dollars. This is a testament to the importance of art in our society, and its value to us as individuals.

What Is the Difference Between Digital and Fine Art?

Digital art is the term used to describe art that has been created or modified using technology. Whereas fine art refers to art that has been traditionally made by hand. Digital art can provide a platform for experimentation and exploration of new ideas. However, it does not necessarily capture the same essence as traditional works.

The practice of digital art can have applications in decorative, or applied arts. However, digital art created purely for aesthetic purposes can be considered as fine art. Digital art can now closely emulate traditional mediums. Artists can create brushes that appear to mix like oil paints, with the illusion of texture.

Art Mediums in Fine Art

Fine art encompasses a broad range of mediums, each offering its distinct texture, colour intensity, and artistic nuances.

- Oil : Known for their rich, vibrant colours, oil paints are widely used in fine art for their blending capabilities and long drying time.

- Watercolour: Watercolour paints are praised for their transparency and ability to create delicate, light washes of colour. They are typically used on paper mediums.

- Acrylic: Versatile and fast-drying, acrylic paints can mimic oil effects, and can be used on a variety of surfaces.

- Pastel: Pastels, available in stick form, provide artists with the ability to create soft, vibrant colours and work exceptionally well for capturing light.

- Gouache: Known for its opacity, gouache is a unique type of watercolour that can be used to create bold, bright works of art.

- Sculpture: This three-dimensional form of art can be made from a variety of materials, including stone, metal, glass, wood, and clay.

- Charcoal: Charcoal is an excellent medium for creating high contrast and detailed sketches.

- Graphite: Commonly used for preliminary sketches, graphite is known for its various levels of hardness that can create different shades and depths.

- Ink: Inks can be used for drawing, often with a pen or brush, or for creating washes of colour.

- Textiles: Textile art includes art that uses plant, animal, or synthetic fibers to construct practical or decorative objects.

- Ceramics: This involves creating art forms from clay which are then hardened by heat.

Different Art Movements

Throughout the centuries, different art movements have emerged and changed how we view and create art. From the Renaissance to Surrealism, each movement has had its own particular style and purpose. Each of these styles has helped shape modern-day fine art as it is today, inspiring many artists to create artworks of their own.

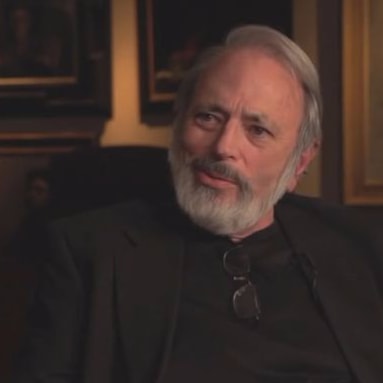

What is Fine Art and Why Realism? by Fred Ross

Home / Articles

What is Fine Art and Why Realism?

by Fred Ross

Chairman and Founder of the Art Renewal Center Keynote Address delivered at The Realist Art Conference November 3, 2015 Ventura CA.

Click the above video to watch the recording of the Keynote Address.

Hello, I'm Fred Ross, founder and Chairman of the ARC which stands for the Art Renewal Center. In 1974 I earned my Masters of Art Education at Columbia University, and came away deeply disillusioned in what the art world had become. Three years later, in 1977 I visited the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, MA. and saw for the first time a painting by William Bouguereau titled Nymphs and Satyr painted in 1873, and the power and beauty in that one work led me to investigate what had actually occurred in the 19 th Century which soon led to the realization that the art history of that period was nothing but a series of distortions and lies. And this fiction was being taught as art history in virtually every college and university art department in the world. I have spent the last 40 years unraveling what occurred and seeking out the truth.

It is indeed an honor and a real treat to be speaking at this year's TRAC conference and to be able to share my thoughts just what exactly is fine art and why an accurate understanding of the meaning and purpose of fine art leads inexorably to concluding that only Realism, that is, images based on the real world in which we live, play and work, are capable of meeting the definition of fine art and able to meet the highest and most advanced goals to which fine art aspires. To properly explain this, we need to go back to foundational basics.

What is Fine Art: What is Fine Art!

Artists create things which have meaning to them and which they hope will have meaning to others. The artist wishes to communicate meaning of one sort or another to those who view their work.

Therefore it seems very clear that: the purpose of fine art is communication. Not just any communication, but in particular those things which give expression to those moments in life that all people have which are experienced as meaningful and emotionally charged.

Fine art fills a basic human need in its ability to communicate and capture and express ideas about life and living which people care about after their basic biological needs are filled. People need to share their lives and feelings with other people and this is done through communication which helps give meaning to our lives.

Most communication is in spoken and written language. Fine art also communicates, which it does best when it successfully captures, depicts, and expresses our shared humanity: how we feel about ourselves, other people and the world around us. It may be seeking to capture an emotional state of mind like reverie, jealousy, joy, sadness, fear, etc., or it may attempt to tell a story like Ghiberti's famous scenes from the Old Testament on the doors of the Baptistery in Piazza Duomo in Florence or Norman Rockwell's Home from War . If someone with little skill attempts a work of fine art it will likely be unsuccessful or awkward and fail, but an attempt at fine art was still made as opposed to an attempt at fine craft. Failure to achieve doesn't turn fine art into craft or vice versa. All of the other crafts and sciences have a utilitarian purpose or a purely decorative purpose, but in fine art, human beings endeavor to look at themselves and others, to contemplate the nature of living as a human being, and to find ways of capturing, expressing and communicating with empathy, passion and compassion the road we all must take between birth and death. So, the purpose of fine art is similar in its goal to the purpose of poetry, fine literature or theatre.

Based on the above, I posit:

The visual fine arts of drawing, painting and sculpture are best understood as a language... a visual language. Very much like spoken and written languages, it was developed and preserved as a means of communication. And very much like language it is successful if communication takes place and unsuccessful if it does not.

This simultaneously helps define the term "Fine Art." So fine art is one important way that human beings can communicate.

This realization conversely poses the question:

Can it be fine art if it does not communicate or does not even attempt to do so?

Communication can only occur if the language of the speaker is understood by those who are listening. An absolute necessity for communication is that the language employed has vocabulary and grammar shared by speaker and listener or by writer and reader and therefore logically by painter and viewer. The earliest forms of written languages used simple drawings of real objects to represent those objects as observed in Hieroglyphics and the earliest cave drawings. The origins of written language and the origins of fine art overlap in this nearly identical way. Without a common language there is no communication and no understanding, whether in writing, speaking or fine art. All three have the uniquely human purpose of describing the world in which we live, and how we feel about every aspect of life and living. As a language, fine art is like all of the hundreds of the spoken and written languages that are capable of expressing the enormous, limitless scope of human thoughts, ideas, beliefs, values and especially our feelings, passions, dreams, and fantasies; all the varied experiences and stories of humanity.

The vocabulary of fine art are the realistic images which we see everywhere throughout our lives. The grammar is made up of the rules and skills needed to successfully and believably render the images and ideas and seamlessly connect them together.

Here are some of the rules or grammar which hold together the real objects or vocabulary of the visual language of fine art: finding contours, modeling, manipulating paint to create shadows and highlights with the use of glazing and scumbling which enhances the form through layers of pigment, use of selective focus, perspective, foreshortening, compositional balance, balancing warm and cool color, lost and found shapes and lines, etc.

Now ponder this self-evident truth: Even our dreams and fantasies as well as all stories of fiction, which are not real, are expressed in our conscious and subconscious minds by using real images, none which look like modern art . Therefore non-objective abstract painting does not reflect the subconscious mind . Dreams and fantasies do that and artwork can also do that; but only by using real images and assembling them in ways that feel like fantasies or dreams.

Compare these now to two artists who are considered amongst the greatest Abstract Expressionists: William De Kooning and Jackson Pollock.

What is being communicated in these two Modernist paintings and which method of working is more successful way to communicate, realism or abstract?

Universality

Furthermore, the vocabulary of traditional realism in fine art has something which makes it unique, in one important way... the language of traditional realism cuts across all those other languages and can be understood by all people everywhere on earth regardless of what language it is they speak or write. Thus Realism is a universal language that enables communication with all people, past... present... and future. Modernist and abstract art is the opposite of language because it represents the destruction of the language of fine art and is therefore the absence of language. The absence of language means the loss of communication; it takes away from mankind perhaps our most important characteristic... that which makes us human... the ability to communicate in great depth, detail and sophistication; and in the case of fine art, the Modernist paradigm banished the only universal language that exists: realistic imagery, with the techniques and skills required to achieve it. This knowledge had grown, developed, and was carefully documented and preserved as it was passed down for centuries from masters to students.

The artist tries to express his or her feelings about life and to communicate with others through their art. The artist has found a constructive way to deal with the truth of human existence, the knowledge that we all die. Instead of shaking their fist at eternity and being overcome by sadness, hate and depression, the artist "rages at the dying of the light" (to quote Dylan Thomas) seeking to overcome for themselves and their audience the basic loneliness of existence. They strive not to be engulfed by despairing the brevity of life, or the absence of meaning that we face in the wake of the certainty of death and the certainty of loss. Focusing on those negatives leads to an absence of meaning, which is the central belief of Existential Nihilism. It's no wonder then that Existentialism would espouse Modern art or that Modern artists would associate their work to Existentialism.

Fine art finds meaning instead, by using the infinite creativity of the human soul, and the limitless brilliance within the human brain to find endless ways of communicating with each other about our difficult and differing journeys and odysseys that can and do occur through life. The essence of fine art had always been to express things which people find as meaningful whether religious paintings of the early and High Renaissance or genre paintings of the 17th and 19 th centuries.

We all are born helpless, utterly dependent and profoundly ignorant about who we are and what lies ahead. We all yearn to be loved, to be understood, and we all need and want mentors. We want them to be kind and patient and to teach us what we need to know about life and navigating society. We want to be respected. During adolescence we invariably explore paths to happiness which can be dangerous and destructive. We all want to find work that inspires us and is fulfilling. We want families and if we have children we want to be good parents and to offer better lives to them. We all must endure sickness and the eventual pain of death and witness those we love suffering. Human beings all have universal and shared characteristics as well as an infinite variety of unique and different traits which constitute our differing personalities. We all want and need love and companionship, warmth and friendship. We also have pride and are vulnerable to having our feelings hurt or to being ridiculed, or feeling envy or jealousy.

Fine art can deal with all or any of the seemingly endless arrays of feelings and experiences that benefit, excite, terrorize or plague humanity. This is the broader definition of "beauty" and the fundamental aesthetics that defines fine art. The artist is said to be successful who can communicate some portion of human experience and do so with beauty, poetry and grace. As with prose, poetry or theatre, there are subtle and nuanced ways to express ideas and feelings and to captivate and inspire one's audience, or there are blatant, self-conscious, awkward, inane, childish attempts which fail as works of fine art, as well as en endless continuum of degrees of success or failure.

Often people ask how sad or negative subject matter can be beautiful. The beauty is achieved by poetically communicating some aspect of the human condition with empathy so that the viewer/audience can relate to how it might feel to actually live through some unhappy or horrible experience. Or perhaps they have already lived through such an experience which evokes similar emotions. The artist is telling a story that has strong meaning due to some aspect of their personal history. The viewer says to themselves either consciously or subconsciously, "I know how you feel." Fine art helps people connect with one another and can even act as a pressure valve releasing tensions and can reduce the likelihood of conflict. Uncomfortable or unpleasant subjects may not be pretty but they can be very beautiful and we can learn from them. Modern works with their indecipherable meanings can do the opposite: alienate and agitate us. Often Modernist works are praised for doing just that. Their stated goals are often to shock or insult.

Often when criticizing a movie or show or a work of art we hear people say "It doesn't speak to me" or "It doesn't do anything for me". What they're saying is it doesn't communicate to them or at least not about something they care about. Most people who view abstract Minimalist or other Modern art forms you will hear say that. Those in the Modernist movement will say they are ignorant and not sophisticated enough to see what's there. In other words, it's not the fault of the artists that their labors have produced something that doesn't communicate, it's the fault of the viewers for not having learned the Modernist rationale for making objects without meaning. But when it comes to great theatre, poetry or prose, most people can understand what is being said and intuitively find the beauty that does "speak" to them.

Academically trained realist artists of the 19 th Century were accused of being elitist. But what could be more elitist than saying "only we enlightened" can understand what Rothko, Warhol, de Kooning and Pollock were saying. If we don't like it, they say: "You all are too ignorant, tasteless and clueless to get it." They call realist art simple and less sophisticated, because its meaning is too obvious and easy to understand. In other words if a work succeeds in the primary purpose for which it was created, human communication, that very success becomes the reason it is denigrated. The living realists of today as well as all realist artists of the past were expressing universal themes and reaching out to all people of all time. What could be elitist about that? Realist paintings of the past as well as those today are intended to bring humanity closer together.

Let us once and for all put a spike through the heart of the Modernist argument that Realism is trite, petty, inane and devoid of meaning. For if that is true of technically skilled Realism, then it would equally have to be true of all poetry and literature which also uses a vocabulary and structure which are recognizable by writer and reader, speaker and listener; as it is too by painter and viewer.

In theatre the task at hand is whether the playwright, director and actors can enable the audience to "suspend disbelief." They endeavor to create a world in which the storyline of their play, or movie takes place. For this to work, the things that happen "the business" and the dialogue need to seamlessly work together in a manner that feels logical and believable. Even in magical realism, science fiction, and fantasy the goal is to make it all feel possible.

We all know that the movie or live show has been carefully written and orchestrated. Each word that is said, every movement the actors make, and each element of the set design, backdrops, and props that appear and are seen or used, have all been planned, usually down to the smallest detail. The actors need to make it seem like they are saying their lines as if they were spontaneous responses to things that might be said in the situation or circumstance being portrayed. Indeed, some directors allow ad-libbing and extemporaneity from their actors to enhance believability. But, careful planning is the underlying "truth" of what is going on. For a theatrical performance to succeed as a work of art, it all must seem to be happening spontaneously as it would in real life. In that context, the writer can explore ideas about life that he or she chooses; whether it is about poverty caused by an indifferent or malevolent government or corporations, as seen in Grapes of Wrath , or the waste of life and the ennui and indolence that accompanies inherited wealth in The Great Gatsby , or the injustices and corrupt society and its effect on otherwise good people portrayed in Les Miserables . All these books have been made into successful theatrical productions and films that can be said to have reached a level of fine art through the language of theater with its similar vocabulary and grammar of realism. They have culminated in productions that suspend the audience's disbelief and they have each created their own unique forms of beauty.

In poetry, two good examples would be Omar Khayyam's Rubaiyat , or Robert Frost's Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening , both poems are about confronting death and characterize how to live one's life, knowing that the grim reaper lies just over the horizon. These two poems use the language of words to deal with difficult subject matter in a beautiful way and all the images conjured are ones from our experiences in reality.

If the structure of the work of art is awkward or self-conscious, so that the details of how it is has been constructed is evident to the listener or viewer, the artist or author is thought to have failed. In theater, if the writing is fine, but the acting is terrible, then we might blame the actors or the director. But in every case you have the work of art constructed from elemental parts and assembled by the writer, director, composer, musician, actor, singer, dancer, painter or sculptor in a work that is highly organized and embedded with a level of sophistication only found in human beings.

The importance in understanding this underlying process becomes very evident if we now look at the debate that has occurred between Modern art vs. Traditional art. The Modernist artists who are credited with the origins of Modernism are celebrated for pointing directly at the underlying reality of what fine art is constructed from. Cezanne, Manet and Matisse we are told showed us the "truth" that a painting is really just colored paint applied to a flat canvas, paper or surface.

Modernism claimed traditional art, as taught in the art academies throughout the 19 th Century, was engaged in lying to the public, trying to make the flat canvas look three dimensional; trying to use drawing, modeling and perspective to create illusions of space; trying to make you believe that you are perhaps looking into a room where people are doing something or at a landscape outdoors, etc. ... all deceptions and lies. The job of the artist then, during Modernism's 20th century ascendancy, was to make painting have value by focusing on the one aspect of what a painting was that no other art form had, which was the flatness of the picture plane. Focusing on the formal, underlying, fundamental components of art, became more important than focusing on why art existed in the first place, which was to communicate ideas, feelings, values and beliefs and all human experience.

Art's purpose was to justify itself, which ironically pretty much cancelled out all of its purpose and value. Here is a quote from Clement Greenburg that makes this point:

1 Clement Greenberg, 1960. . Greenburg, according to many Modernists "... was probably the single most influential art critic in the twentieth century. Although he is most closely associated with his support for Abstract Expressionism, and in particular Jackson Pollock," From The Art Story . It was the stressing of the ineluctable flatness of the surface that remained, however, more fundamental than anything else to the processes by which pictorial art criticized and defined itself under Modernism. For flatness alone was unique and exclusive to pictorial art. Because flatness was the only condition painting shared with no other art, Modernist painting oriented itself to flatness as it did to nothing else. 1

The truth was that there were no people, no landscape, no real objects to paint other than the concrete reality of the paint and the canvas. The artist, endlessly pointing directly to his underlying materials was the birth of Modern art. Cezanne flattened the landscape, Matisse flattened our homes and families and the so called abstract artists after them, like De Kooning, Stella and Pollock, put it all in a blender and threw it at the canvas, thus making flat color design the end goal of the artist. Expressing and communicating human emotions was not a worthy purpose for art, and so all human emotions were denigrated as petty sentimentality.

The equivalent of this system of thought applied to written languages would be to say that all writing is untruthful and finding the truth can only be discovered by pointing directly to the underlying materials and structure of written words. All that is really there on the page are different shapes of straight or curved or squiggly lines. Since that is closer to the truth than placing meaning in those shapes and lines... than using them to make words and the words to form ideas... that too must be a lie and an unworthy purpose for the writer. Therefore, to bring the analogy full circle... the best book would be one that demonstrates this "truth" with page after page of meaningless shapes and squiggles...thus showing us the modernist's profound definition of truth. How many books and poems would be purchased and read in which all that could be found between the covers were meaningless shapes on every page? Modernism endows the meaningless with meaning. Each of us must decide for ourselves whether there is meaning to be found and if that meaning has great value.

Isn't it just as much a part of the truth that the artist who wishes to express a shared human emotion needs to hide the flatness of the picture plane in order to enable the viewers to suspend disbelief the same way that works in theatre? The truth of fine art is not that it's just a flat plane with colors on it, but that the artist, using the flat plane and colored paints, needs to overcome that major limitation of their materials by creating a scene in which the three dimensions of the real world are mimicked sufficiently well so that he can design and compose a painting on a 2 dimensional surface that can communicate the complexities of a moment in life? Since all such moments occur in a three dimensional world, the artist needs to mimic that world to bring their ideas to life.

Is it petty and banal to show romantic or familial love and caring? Or is it petty banality to spend one's career insisting that the only paintings that have value are those which demonstrate that they are flat?

What then is fine art? And for that matter, what is fine literature, music, poetry, or theatre? In every case human beings use materials supplied by nature (the clay, colors and materials of the earth and the movements and sounds of life) and creatively combine or mold them into something else which is capable of communication and meaning. It is that ability to communicate, whether subtle or blatant, complex or nuanced wherein the value of art lies and makes it worthy of the term "fine art". Modernists like to say "why waste your time doing realism? It's all been done already." That would be exactly like saying "Why waste your time writing anything? It's already all been written. There is nothing left to say."

Illustration

Illustration is often thought of as a lesser form of art. Often we hear people say something like: "That's only an illustration; it's not fine art"

However, given the clear description of what fine art is, that no longer makes any sense. All fine art is illustration. What is different is what is being illustrated and then how well it has been accomplished.

If you look at illustrations in young children's books, often those illustrations are done quickly and the cost and time involved in creating them plays a big role when writer's or publishers choose them.

However, there are illustrations for books and poems which have been created by some of the greatest of artists. Gustave Doré illustrated Dante's Inferno and Edgar Allen Poe's The Raven . Edmund Dulac illustrated Edward Fitzgerald's translation of the Rubaiyat by Omar Khayyam, and Michelangelo painted the Sistine Chapel ceiling with illustrations inspired by the Bible. All of the early and High Renaissance artists illustrated scenes from the Old and New Testaments. 19 th Century artists illustrated Shakespeare, poetry and myths and legends.

The attempt to pigeonhole images that tell a story as illustration which has been separated in many art schools as a lesser form of art is strictly a tactic to degrade all realistic fine art and to further entrench Modernist ideology.

Since, all fine art is representational and since only realistic objects, figures and settings are capable of complex communication, one is drawn to the logical conclusion that all illustration belongs in the category of fine art. The differences are all qualitative: a difference in degree not a difference in kind.

Once we recognize that, we can see that variation in quality can be enormous and it may even be useful but problematic, to make an attempt to create categories along a continuum of some sort based on quality, purpose, and success or failure of the art and artist to communicate or illustrate what was intended.

There also can be qualitative differences in subjects and themes. Some themes are about more powerful emotions or moments during life that therefore have greater potential for achieving the beautiful. For example a painting illustrating wartime wives in 1944 listening to a radio broadcast for the names of the men who were killed, has vastly more potential than a bowl of fruit or a painting of a can of soup. Therefore, illustration and fine art are one and the same and all fine art illustrates something.

Based on these truths, the artwork in this year's ARC Salon competition and by the artists who have joined together at this TRAC conference can now be readily viewed and interpreted without the prejudicial tenets of Modernism ready to denigrate any works constructed by images from the real world. Many of the best works exhibited are sure to generate compelling discussions, and analysis and a vast array of differing opinions as to what has been said and accomplished. It is very much our goal to break through the restraints placed on artistic thought over the past century and open up the limitless source of innovative subjects, ideas and compositions that are available throughout the real world. And by so doing encourage a vast rebirth of creativity for artists and to enable unshackled critical thought and analysis for those who love, seek out and acquire fine art.

Originality

Let us talk now about modernism's obsession with "being original". In fine art the claim that "it's all been done before" places an impenetrable wall of hopelessness in front of any creative pursuit. Imagine becoming a doctor and not being required to learn what is already known? Knowing doesn't stop you from doing something new but it keeps you from wasting your time on searching for knowledge that already exists and is readily available. It also decreases the chance of making very serious mistakes. The refusal to learn from the past will inevitably prevent anything new from actually being discovered, as breakthroughs are always built on the discoveries of those who came before. In the arts, the fear of doing what has been done before places a ball and chain on your mind and on the joy of creativity, one of the greatest joys in life. Only someone who has learned what is already known can strive to create fearlessly and will have any chance of actually creating something new. For invariably, humankind has a history of creative accomplishments going back thousands of years, so someone who is creative will surely stumble upon many things that have been thought of and done before in advance of achieving the truly original. And if we are honest, the most favored subjects are as old as humanity itself and there are unlimited and original ways in which they can be expressed again and again.

Modernism in its need to banish anything seeming unoriginal, has banished all of the tools and skills with which original work was accomplished and then tells their artists without skills and without tools to go and create worthwhile works of fine art. Since there is no meaningful language in their art, a thousand words are needed to imbue it with meaning. Actually the words have to be incredibly creative and shrewd to convince otherwise educated and intelligent people that something of value is present when little or nothing is there.

Modernists create art that is about art: "art about art," whereas all the great art of the past was "art about life".

A painting should no more attempt to make the viewer conscious of the paint and canvas than the writer should make the reader conscious of the ink or type of paper being used, or for that matter than the film maker should make the audience endlessly aware of the kind of cameras being used or that the movie is actually composed of a fast moving series of still images.

The resurgent realist artists whose ranks are rapidly expanding in the 21 st century, consider their materials and skills as a vital means of communicating artistic subjects and ideas. Modernism banished the real world from the tools they could use. Of course, without the full vocabulary of the real world to draw and to draw from, there is no way for artists to express complex or subtle ideas After all, any three-year-old who is taken to a museum knows that the canvases are all flat. How great then was it that Cezanne and Matisse spent the rest of their careers saying it over and over again? Is there any need in these abstract works to suspend disbelief? Or is "belief" instead compelled, not by the acting, writing, drawing or painting, but instead by the intimidation of power and position?

Prestige Suggestion

Do students believe in this new inheritor of Western Art? Or does not believing in it threaten their grades and positions (and the wallets of those invested in such art)? It is amazing how the need to avow one's belief repeatedly in something that was previously difficult or impossible to believe, will become increasingly easier when supported by figures of authority. A useful term for this phenomenon is " prestige suggestion ".

What Modernists have done has been to aid and abet the destruction of the only universal language by which artists can communicate our humanity to the rest of, well, ... humanity. They then have built up a labyrinth of justifications and blocked all other viewpoints. If the history of what actually took place is not to be lost due to the transitory prejudice and taste of a single era, then we must question any practice that deliberately suppresses documented evidence. Art history must not be reduced to little more than propaganda directed towards market enhancement for valuable collections passed down as wealth conserving stores of value. Successful dealers, who derived great wealth by selling works created in hours instead of weeks, had little trouble lining up articulate, eloquent and persuasive masters of our language to build complex portrayals presented everywhere as brilliant analysis to justify what are really very uncomplicated, unsophisticated and simplistic works; creations which arguably should have and would have been rejected out-of-hand but for their disingenuous and cunning sophistry.

There is a difference between value due to prestige suggestion and value due to intrinsic quality. Surely, in the search to define beauty, we need to understand that difference. We should be able to see through prestige and determine when we are in the presence of the truly beautiful, versus a work that's greatest quality is the prestige attached to the name of the artist or the movement. In this way a canvas with little intrinsic value that has the signature of De Kooning, Pollock, Rothko or Mondrian on it, are assigned high values because people with a PhD or the title of Professor or Museum Director next to their names have told us what to think about their worth. Then, major dealers or auction houses have assigned estimates of millions of dollars to their work. Most people do not feel themselves knowledgeable enough to know what has or does not have value and rely on what "authorities" tell them. This is "prestige-suggestion". Even if their instincts are to reject something, they keep silent lest they expose themselves to ridicule for being considered ignorant, tasteless or out-of-touch, succumbing to "social pressure".

Along with "prestige suggestion", there is a second very useful expression that aids us in understanding what has occurred and how Modernism, after gaining ascendance, has been able to maintain its position. That term is called " Art-speak ". Art-speak is a contrived form of language, which uses self-consciously complex and convoluted combinations of words to impress, mesmerize and silence opposition. Art-speak attributes to Modernist works glorious positive qualities which are just not there at all . "Art-speak" is generally used by people in positions of power and authority and in combination with "prestige suggestion" is ultimately employed to silence contrary instincts and ideas to prevent people from identifying honestly what has been paraded before them.

Art-speak, a way by which complex sounding words and concepts are used to create the illusion of something being more than it is as a method to create value, meaning and importance that drastically outweighs what is actually there. Sotheby's Contemporary Department said that "Cy Twombly's epic 1964 canvas 'Untitled (Rome)' is one of the highlights of our Contemporary Art Evening Auction on 12 February 2014." But what is even more amusing is the video created about the piece for the sale. If one looks at it objectively we can see that the painting really looks like the type of doodling that many peoples' two year old children do. At one point the video flashes to a scribble with pencil and say's it shows the artist's "growing confidence". Evidently there are many in the art world who think adults scribbling like children is something people should be willing to pay big bucks for. Although the piece does look like one a child would do, this doodle sold for 12,178,500 British pounds, over 20,000,000 US dollars.

Watch the video above to view this incredible example of art speak. Everything about it from the word choice to the British accent to the dramatic music oozes value, when really the work is nothing but scribbles.

Art Speak Examples

The first: It's from the curator of Contemporary Art at the National Gallery in Ottawa speaking about the work of a young 'conceptualist' she regards highly. (The work itself was nothing but a device that blew out smoke intermittently.)

I think that certain issues being foregrounded in it [the art in question], such as its modesty and its involvement with everyday activities--as opposed to a sequestered studio practice--are probably quite indicative of current directions in art. You could say that this work is riding the crest of a wave, in its emphasis on communication, in its engagement with the everyday, in its involvement with ephemeral experiences.

Secondly: I have a quote from Catherine Perret describing current trends in Modern and Post Modern art.

Catherine Perret is associate professor of modern and contemporary aesthetics and theory at Nanterre University in Paris.

She's widely published and accepted as an authority on modern and post-modern art.

Catherine: "Take Marsilio Fiscino and/or Giovanni Pico as examples. Their thinking typically placed the reign of significance in-between the vast remoteness of spiritual infinity and the baseness of present materialism - therefore concentrating on the zone of transformational actions of humans that lead to a natural magical alchemy. This noology is about knowledge that can transform things and states of the system. In that sense I am maintaining that we are leaving the age of sterile reductive analysis and entering into one of fecund synthesis; much like the poetic-mythic-scientific age of the early Renaissance. The binding force of this synthesis is certainly inter-subjective pleasure (art) and a lust for yeasty comprehensions out of which new possibilities grow. These comprehensions are obtained by experiment/chance/inner-risk - though need not be verified, nor repeated. Indeed they should not be. It is about a search for originality in that sense. The new noology's validity is obtained through the force of its correspondences and its breath of connectivity. The resulting pan-panoramas will luxuriate this era and be the counter-attack to fundamentalist repression as its imminence will supercede our mistrust of irrationality and lead us into a qualitative approach by escaping locked down definitions. In some ways it is a development of Nietzsche's Gay Science."

And there it is. I must tell you un-categorically and without any equivocation: There is no idea, concept or thought which cannot be expressed with direct and fairly simple language. But simple language would not work as well to be confusing. If the words could be readily understood opposition would be far more likely.

2 These letters have been written to the organization for which I am Chairman, The Art Renewal Center, which is a not-for-profit educational foundation. Many of these letter have been published in ARC Letters on the ARC website. The "authority" of high positions, and the "authority" of books and publications, and the "authority" of certificates of accreditation, all work in combination to impress and humble and silence those whose common sense would otherwise rise up in opposition. Without a doubt, people otherwise would clearly see this art for what it is — evident nonsense — if it's supposed value had not emanated from the pretentious mouths and pens of those with such a preponderance of "authority" to back them up. Many students and even teachers have come forward to report how traditional realism has been virtually or actually banned from their art departments. They want to share their sufferings at the hands of Modernist educators, and ask what they can do. 2

Banning of ideas and not permitting free and open debate has been a problem throughout history. Most often relating to religion or politics, it rears rear its ugliness in other fields as well. John Stuart Mill's remarks on speech suppression are as alive and accurate today as they were two hundred years ago:

3 John Stuart Mill's essay On Liberty (From Great Political Thinkers by Wm. Bernstein p.569) Where there is a tacit convention that principles are not to be disputed; where the discussion of the greatest questions, which can occupy humanity, is considered to be closed, we cannot hope to find that generally high scale of mental activity, which has made some periods of history so remarkable. However unwillingly a person who has a strong opinion may admit the possibility that his opinion may be false, he ought to be moved by the consideration that true it may be, if it is not fully, frequently, and fearlessly discussed, it will be held as a dead dogma, not a living truth. 3

Without a dynamic living network of experts teaching technical knowledge in drawing and painting, it will never be possible for college and university art departments to have students who are able to enrich the debate and the academic environment for all students by producing works of art that are capable of expressing complex, vital and spirited ideas. To forbid these skills to be taught on campus in any real depth is as ridiculous as having a music department that refuses to teach the circle of fifths or only teaches three or four notes from which they insist all music must be composed. It is as absurd as having an English department in which all words that had recognizable meanings were forbidden and only writing without words or sentence structure would be admissible.

If there was nothing to be ashamed in their teaching methods and in their results, they would welcome the chance to confront the ideas that they should be well equipped to refute. They have a solemn duty to maintain the integrity of thought made possible by what has been handed down to them by those artists, writers and thinkers before us, who established a vast, complex and rich system of training with which to teach and pass on a wealth of knowledge. Deliberately preventing access to this information is crippling to the goals of education and a severe obstruction to insuring a society based on freedom of thought without which progress is impossible. Where is it more important to vouchsafe these principles than at our nation's colleges and universities who have a duty to expose their students to responsible opposing views in all fields of study?

Traditional skill-based art in recent decades has had very few proponents, ceding nearly a century to an ascendant modernist leviathan. Ironically, that century has seen the greatest strides forward in every other field of human endeavor. If the proponents of realism are as correct as it seems, the art world is woefully behind our times and will need to do a lot of catching up.

The new Realism movement now has thousands of artists. That is a staggering turn-around from the handful who were working 30 years ago. There are over 70 ARC Approved Atelier based schools today and several waiting to be vetted. And there are dozens of organizations helping to support their efforts of these artists. There are many upscale art galleries in major cities throughout the world who concentrate on art with images from the real world. You have all taken great strides forward in reclaiming our century's long heritage in Realist fine art. We are now seeing solid indications of the rich creativity developing at the heart of the 21 st Century art world. The exhilaration and optimism which flows forward from here could not be more thrilling or more exciting. I can't wait to see the magic and beauty that is in store for us as these artists are inspired by an avalanche of original perspectives, innovative methods, and brilliant game-changing subject matter of a rapidly growing Realist movement... as artists share their ideas together seeding and cross pollenating a landslide of creative and innovative thinking that will lead us to ever more poetic, inspirational and beautiful artwork in the studios, salons and exhibitions in the years that lie ahead. Just half way through the second decade of the first century of this the third millennia, we are truly at the very beginning of a new era that celebrates the beauty and poetry of the human soul. Thank you.

Clement Greenberg, 1960. . Greenburg, according to many Modernists "... was probably the single most influential art critic in the twentieth century. Although he is most closely associated with his support for Abstract Expressionism, and in particular Jackson Pollock," From The Art Story .

These letters have been written to the organization for which I am Chairman, The Art Renewal Center, which is a not-for-profit educational foundation. Many of these letter have been published in ARC Letters on the ARC website.

John Stuart Mill's essay On Liberty (From Great Political Thinkers by Wm. Bernstein p.569)

Founder and Chairman of the Art Renewal Center, Ross is the leading authority on William Bouguereau and co author of the recently published Catalogue Raisonné William Bouguereau: His Life and Works .

Further Reading

Abstract Art Is Not Art and Definitely Not Abstract

ARC Chairman Speaks at the Ducret School of Art

Oppressors Accuse Their Victims of Oppression

by Brian Yoder

Oil Painters of America Keynote Address

The Great 20th Century Art Scam

The Philosophy of ARC

A blog by Saatchi Art

- The Other Art Fair

- Artist Tips

November 17, 2016

Evangelyn Delacare

About Art History 101

Learn about the artists, movements, and trends behind your favorite styles of art—from Classical to Contemporary, and hitting everything in between, including Street Art, Pop Art, Impressionism, and Abstract Expressionism.

- Art History 101

What is Fine Art?

November 17, 2016 Posted by Evangelyn Delacare

Have you ever wondered what the term “Fine Art” really means? While contemporary semantics may differ, read on to discover the historical origin of this phrase.

The notion “art for art’s sake” arose at the turn of the 19th century, when artists grew increasingly more inclined to use art as a freedom of expression, rather than to document and represent historical and cultural events. Complementing this notion, the term “fine art” was used to differentiate works by artists who were the sole agent of creative expression from works that were created by commission, or objects with utilitarian functions that fall into the category of craft or decorative art.

Read on to learn more about the history of Fine Art and its contemporary usage…

Historically, fine art encompassed painting, sculpture, architecture, music, and poetry. Especially concerning painting and sculpture, works considered to be fine art are created primarily for aesthetics and from the innate desire for artistic expression. Some of the most famous and prominent works of art – “The Statue of David” by Michelangelo, “Mona Lisa” by Leonardo da Vinci, “Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer” by Gustav Klimt – are not technically considered to be fine art , as they are all commissioned works by patrons.

Stemming from the rise of Romanticism, a 19th century art movement focusing on beauty and the sublime rather than classical structures of the past, artists and artworks sought to detach themselves from creating utilitarian works. One of the first artworks considered to be fine art is “Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket” by American artist James Abbott McNeil Whistler, who used color and mood to convey abstraction of the scene, a practice not widely accepted in art circles at the time.

With the advent of modernism, fine art became less about aesthetics and a marker for refined taste, and shifted focus to challenging broader notions of art. Amidst this shift, the avant-garde movement also emerged, which prioritized concept and intellectual purpose over aesthetics . Modern works such as “The Fountain” by Marcel Duchamp and “Starry Night” by Vincent van Gogh are in accordance with the definition of fine art as they express the true intentions of the artists without restriction placed by a patron.

Today, the definition of fine art has expanded to include several more categories such as film, photography, conceptual art, and printmaking.

Love reading about all things art? You can have articles from Canvas, curated collections, and stories about emerging artists delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for the Saatchi Art Newsletter .

Browse Fine Art Paintings

About the Author

Evangelyn Delacare is the Associate Curator at Saatchi Art. Need help finding art? Contact her via our free Art Advisory service at saatchiart.com/artadvisory.

Select Works for Sale

Sparks of palms 2,950

Ana Beltrá View artwork

broken mug 880

Brittany Loar View artwork

Close To The Edge Of A Romantic Thought 760

Elena Erickson View artwork

Composition (the lovers) 2,300

Bruno Varatojo View artwork

Orange Boy 2 340

Patricia Derks View artwork

interior 9,850

Tasos Chonias View artwork

Still Happy - Tiger 880

Rusudan Khizanishvili View artwork

Untitled 1,640

Anya Enot View artwork

You Might Like

One to Watch

Ecaterina vorona’s enchanting figures.

Moldovan painter Ecaterina Vorona focuses her work on expressive, colorful …

Art We Love

Collector favorites: bestselling artists of july.

Ever wondered what other people are buying for their personal art collections? …

Jürgen Katzenberger: Color and Shape

German painter Jürgen Katzenberger’s geometric and abstract works are …

Collector Favorites: Bestselling Artists of June

Seonmi Kang Finds Rest Beneath the Moon

Korean artist Seonmi Kang uses traditional Korean materials to create her …

Balcones Artist in Residence at The Other Art Fair Dallas: Dora Reynosa

The Other Art Fair has partnered with the award-winning Balcones Distilling to …

You are already subscribed

Congratulations!

You successfully signed up

Sign up for our email list

Find out about new art and collections added weekly

Fine Art Definition – Explore the Meaning of the Types of Fine Art

The meaning of the term “fine art” has evolved and transformed over time. Fine art is generally understood as something that appeals to our visual or auditory senses and is produced through a creative process. This short article will take a closer look at how we define and understand the term “fine art”.

Table of Contents

- 1.1 Types of Fine Art

- 1.2 Fine Arts vs. Crafts

- 2 A Shift in the Fine Art Definition

- 3 Famous Fine Art Paintings

- 4.1 Who’s Afraid of Contemporary Art? (2020) by Jessica Cerasi

- 4.2 How Photography Became Contemporary Art: Inside an Artistic Revolution from Pop to the Digital Age (2021) by Andy Grundberg

- 5.1 Is Graffiti Art?

- 5.2 What Is the Most Expensive Work of Art?

- 5.3 Why Are There So Few Famous Female Artists?

What Is Fine Art?

Fine art, sometimes also called high art, commonly refers to a form of art that is aesthetically pleasing and that takes a certain set of skills to achieve. Examples typically included painting and sculpture. This understanding of fine art is often also called “art for art’s sake” and it is generally seen as being superior to functional art , such as decorative vases.

Fine art is also generally seen as superior to “applied art” or “craft”, which are commonly also seen as utilitarian activities. This understanding of fine art is, however, quite limited and has been challenged and extended as new philosophies and technologies emerge.

Because of the ever-evolving nature of art, it is nearly impossible to provide a fixed fine art meaning or definition.

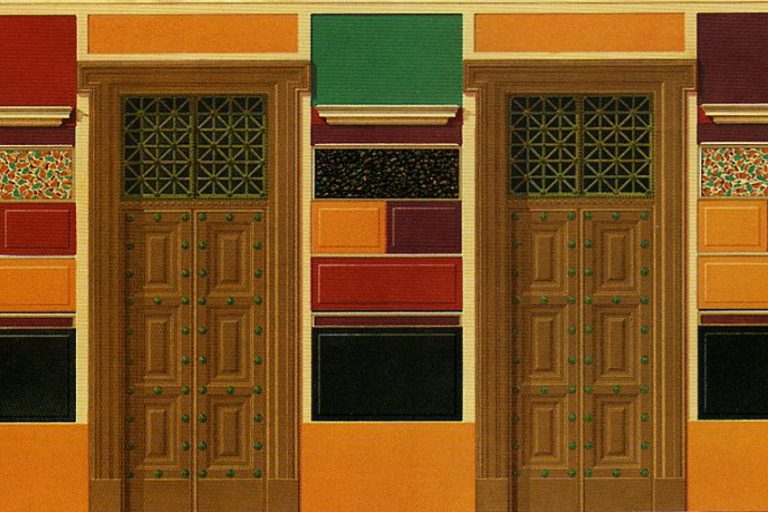

Types of Fine Art

Just as the definition of fine art is blurred and ever-changing, so are the lists of mediums used by fine artists. The list below of fine art examples is thus sure to change over time as technology changes and with the emergence of new artistic inventions. However, based on our current understanding of fine art, we can include the following fine art examples in our fine art definition:

- Printmaking

- Installation

- Fine art photography

- Conceptual art

- Textile arts

- Performing arts

- Digital art

- Mixed media arts

Fine Arts vs. Crafts

There used to be a quite rigid understanding between fine art, which was seen as purely aesthetic, and craft, which was seen as functional. In the 20th century, when the term “visual art” became more prolific, the lines between fine art and craft became blurred. Mediums like silkscreen printing, which was predominantly a functional medium used for advertising are now also considered a medium of fine art.

Ceramics is another example of a medium that used to fit exclusively as a craft but can now also be considered fine art.

A Shift in the Fine Art Definition

The biggest shift in our understanding of fine art happened in the 20th century. One of the seminal moments that challenged our understanding of the meaning of art is when Marcel Duchamp submitted a porcelain urinal as his artwork to an exhibition in New York City in 1917.

The artwork, titled “Fountain”, asked the public to consider what we define as art. Duchamp made a statement saying that anything can be seen as art when it is placed in the right venue.

With this, Duchamp not only challenged the dominant fine art definition, but also the power that art institutions have to determine what is considered art. Artists continued this kind of intellectual experimentation in movements such as minimalism and conceptual art .

By the 21st century, there were many more mediums that were included in the fine art definition.

Famous Fine Art Paintings

Below is a list of some of the most famous fine art paintings. This list includes fine art painting examples from the enlightenment era to modern art and the avant-garde. Below are 30 of the most famous paintings from western art history.

| 1434 | Oil on oak panel | ||

| 1484 – 1486 | Tempera on canvas | ||

| 1495 – 1498 | Leonardo da Vinci | ||

| 1508 – 1512 | Michelangelo | Fresco painting | |

| 1503 – 1519 | Leonardo da Vinci | Oil on popular panel | |

| 1642 | Oil on canvas | ||

| 1656 | Oil on canvas | ||

| 1665 | Oil on canvas | ||

| 1767 | Oil on canvas | ||

| 1801 – 1805 | Oil on canvas | ||

| 1818 – 1819 | Oil on canvas | ||

| 1863 | Oil on canvas | ||

| 1872 | Monet | Oil on canvas | |

| 1876 | Oil on canvas | ||

| 1889 | Oil on canvas | ||

| 1893 | Oil, tempera, and pastel on cardboard, including a lithograph | ||

| 1899 | Oil on canvas | ||

| 1907 – 1908 | Oil and gold leaf on canvas | ||

| 1910 | Oil on canvas | ||

| 1912 | Marcel Duchamp | Oil on canvas | |

| 1929 | Oil on canvas | ||

| 1930 | Oil on beaver board | ||

| 1931 | Salvador Dali | Oil on canvas | |

| 1937 | Oil on canvas | ||

| 1950 | Oil, enamel, and aluminum on canvas | ||

| 1954 | Oil on canvas | ||

| 1962 | Synthetic polymer paint on canvas | ||

| 1972 | Acrylic on canvas | ||

| 1981 | Acrylic and oil stick on canvas | ||

| 2005 | Cy Twombly | Acrylic on canvas |

Reading Recommendations

The book recommendations below are chosen to broaden our understanding of the meaning of fine art. These books introduce different types of fine art and show how the definition of fine art has changed over time.

Who’s Afraid of Contemporary Art? (2020) by Jessica Cerasi

This book gives the reader a delightful and logical insight into the art world today. While decoding “artspeak”, the author explains and demystifies conceptual art. The book aims to make the sometimes-daunting scene of contemporary art more accessible for a wider audience to enjoy.

- Contains 40 color illustrations of artworks

- A playful introduction to the world of contemporary art

- The perfect go-to guide for looking at contemporary artworks

How Photography Became Contemporary Art: Inside an Artistic Revolution from Pop to the Digital Age (2021) by Andy Grundberg

In this book, Andy Grundberg, who used to work as a critic for the New York Times , unpacks the development of photography as an art medium through the years. Grundberg knew many of the artists he wrote about personally, including Cindy Sherman and Gordon Matta-Clark, making his writing even more personal and engaging. Grunberg writes about his own experiences while he tells us about the 70s and 80s through the medium of photography.

- Part memoir and part history

- This perspective is given by one of the period’s leading critics

- Tells a larger story about the crucial decades of the 70s and 80s

This article aimed to answer the question “what are fine arts?”. While there is no clear fine art definition, we can look at what is historically considered fine art and expect that definition to change over time. Artists and thinkers are constantly challenging our ideas around art and shifting the boundaries of what should be considered fine art. Art enriches our lives and we should try to be open-minded and enjoy the development of art through the years.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is graffiti art.

Graffiti is often accused of being vandalism, but it has a very complicated relationship with art. While some graffiti artists are jailed, others, like Banksy , have received record sales. This is a difficult question that has no clear answer. It might be necessary to consider each piece of graffiti separately by looking at the intention and quality of the work.

What Is the Most Expensive Work of Art?

Many pieces of important art can be found in the permanent collections of museums worldwide, making them, in some way, priceless. Of these works that were sold in the past, the most expensive one was Salvator Mundi by Leonardo da Vinci , painted between 1499 and 1510, which was sold for 450.3 million dollars.

Why Are There So Few Famous Female Artists?

You might have noticed that our list of famous fine art paintings included no female artists. Most people can likely count the number of female artists they know of on one hand. These artists might include Frida Kahlo , Georgia O’Keeffe, Louise Bourgeois, Cindy Sherman, Marina Abramovic, or Yayoi Kusama. And all of these are artists that emerged only during the modern era. Part of the reason for this is that female artists were often overlooked in the past and they were also not allowed in art guilds and academies. This has started to change drastically in the 21st century, and for the first time ever, in 2022, the Venice Biennale has more female artists being represented than male artists in their main exhibitions.

Chrisél Attewell (b. 1994) is a multidisciplinary artist from South Africa. Her work is research-driven and experimental. Inspired by current socio-ecological concerns, Attewell’s work explores the nuances in people’s connection to the Earth, to other species, and to each other. She works with various mediums, including installation, sculpture, photography, and painting, and prefers natural materials, such as hemp canvas, oil paint, glass, clay, and stone.

She received her BAFA (Fine Arts, Cum Laude) from the University of Pretoria in 2016 and is currently pursuing her MA in Visual Arts at the University of Johannesburg. Her work has been represented locally and internationally in numerous exhibitions, residencies, and art fairs. Attewell was selected as a Sasol New Signatures finalist (2016, 2017) and a Top 100 finalist for the ABSA L’Atelier (2018). Attewell was selected as a 2018 recipient of the Young Female Residency Award, founded by Benon Lutaaya.

Her work was showcased at the 2019 and 2022 Contemporary Istanbul with Berman Contemporary and her latest solo exhibition, titled Sociogenesis: Resilience under Fire, curated by Els van Mourik, was exhibited in 2020 at Berman Contemporary in Johannesburg. Attewell also exhibited at the main section of the 2022 Investec Cape Town Art Fair.

Learn more about Chrisél Attwell and the Art in Context Team .

Cite this Article

Chrisél, Attewell, “Fine Art Definition – Explore the Meaning of the Types of Fine Art.” Art in Context. July 26, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/fine-art-definition/

Attewell, C. (2022, 26 July). Fine Art Definition – Explore the Meaning of the Types of Fine Art. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/fine-art-definition/

Attewell, Chrisél. “Fine Art Definition – Explore the Meaning of the Types of Fine Art.” Art in Context , July 26, 2022. https://artincontext.org/fine-art-definition/ .

Similar Posts

Dutch Baroque – The Golden Age of Dutch Art

Roman Art – A Brief Study of the History of Ancient Roman Art

Art Deco vs. Art Nouveau – Distinguishing Between the Two Styles

Gesamtkunstwerk – Explore Gesamtkunstwerk in Architecture and Art

Artist Statement Examples – A Look at Famous Artist Statements

Post-Minimalism – A Detailed Movement Overview

One comment.

that was really helpful

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

The Most Famous Artists and Artworks

Discover the most famous artists, paintings, sculptors…in all of history!

MOST FAMOUS ARTISTS AND ARTWORKS

Discover the most famous artists, paintings, sculptors!

Fine Art: Definition, Meaning, And Its Importance

Written by:

Date Post – Updated:

The world of art is a realm of boundless creativity and diverse expressions. At the heart of this vast landscape lies the concept of fine art—a term that encapsulates artwork created for its aesthetic value and intrinsic beauty rather than for practical or utilitarian purposes

Fine art encompasses many forms, including painting, sculpture, printmaking, photography, and architecture. Read on as we will explore the definition and meaning of fine art , examine its historical significance, and discuss the ten compelling reasons why understanding fine art is essential for artists and art enthusiasts alike.

Table of Contents