.png)

HOW THE TELEGRAPH TRANSFORMED THE CIVIL WAR

“The telegraph has made the war so different from all other wars that it is hardly worth fighting.”

—General William T. Sherman

The American Civil War saw the telegraph transform military communications and the spread of information like never before.

This new technology profoundly impacted how President Lincoln directed Union forces, connected citizens to daily war news, and aided innovative generals.

However, the telegraph also brought vulnerabilities in intelligence leaks and unreliable connections over distances.

As with any leap in communications capability, advantages came with challenges and unintended consequences. The following analysis provides fascinating insights into the telegraph’s Civil War role during those pivotal years of 1861 to 1865.

This important technology emerges as a decisive factor shaping strategy, public opinion, and the ultimate course of the war.

THE TELEGRAPH ALLOWED PRESIDENT LINCOLN TO STAY IN TOUCH

The telegraph was perhaps one of the most important technological advancements utilized during the Civil War, drastically transforming how military communications were conducted.

For the first time in history, near instantaneous transmission of information over long distances was possible.

This proved crucial for President Lincoln in commanding the Union forces.

Whereas in previous wars, presidents and commanders-in-chief would often have to wait weeks or months for dispatches to arrive from the front lines, Lincoln was able to get up-to-the-minute updates on key developments directly from his generals in the field.

This helped him make informed strategic decisions with the best available information, though sometimes that information was incomplete or inaccurate.

Lincoln spent many hours in the telegraph room of the War Department, poring over telegrams.

He could directly consult with Generals Grant, McClellan, Meade, and others without the delays that hampered past presidents. This new telecommunications capability allowed him to more closely follow battles as they unfolded and even recommend specific tactical orders.

While the telegraph did not mean Lincoln micromanaged battlefield decisions, it did enable him to provide oversight and guidance, coordinate movements between theaters of operation, and make critical choices on reinforcing positions or withdrawing troops.

This new executive influence on military operations via rapid communications networks helped turn the tide of war in favor of the Union.

The telegraph profoundly shaped how modern wars could be directed.

NEWSPAPERS WERE ABLE TO PROVIDE NEARLY INSTANT UPDATES

The telegraph radically transformed how the American public received news from the front lines during the Civil War.

For the first time, citizens did not have to wait weeks or months for dispatches to make their way from distant battlefields. The telegraph enabled practically real-time transmission of updates on the war's progress.

Newspapers capitalized on this new communications capability, setting up dedicated telegraph lines with their correspondents traveling alongside armies in the field.

Dramatic firsthand accounts of major battles such as Bull Run, Antietam, and Gettysburg were wired directly back to newsrooms in major cities.

Orders of advance, troop strengths, casualties, and more were relayed instantaneously via Morse code.

The public clamored for these latest telegraphed bulletins, published as "extras" in newspapers to spread the news as rapidly as possible.

People gathered in public squares or outside newspaper offices to hear the war's latest developments. The immediacy of the news via telegraph galvanized public interest and involvement in the war to an unprecedented degree.

Both victories and defeats on the battlefield were immediately known on the homefront, keeping the populace engaged.

The telegraphed war news also increased political pressure on Lincoln.

Military failures showed up rapidly in the headlines, prompting public outcry and triggering congressional action. The telegraph profoundly accelerated the cycle of information and democracy.

This telecommunications revolution massively expanded the public's sense of participation in the war.

People felt intimately connected to distant events and military affairs for the first time, thanks to the shrinking of space and time by near instantaneous telegraphic transmission.

The nation's enthusiasm and emotions shifted with each dramatic update.

THE TELEGRAPH LINES WERE TARGETS FOR DESTRUCTION

The telegraph lines that stretched across the theaters of the Civil War were vital for communications, but also vulnerable.

Both the Union and Confederate armies specifically targeted the enemy's telegraph lines as objectives in campaigns and raids. Severing these lines could provide a critical strategic advantage on the battlefield.

Cutting the telegraph severed the nervous system of coordinating armies over distances.

It left generals blind and deaf to developments outside their immediate vicinity. Isolated from orders and intelligence updates, momentum could stall. Opportunities emerged for audacious flanking maneuvers or surprise attacks.

Cavalry raids behind enemy lines made for ideal telegraph destruction missions.

Legendary generals like J.E.B Stuart and Bedford Forrest sent riders to cut telegraph poles and rip down miles of wire.

Saboteurs also quietly snipped wires under the cover of darkness.

Defending and repairing telegraph lines became a constant effort.

Special details of soldiers guarded key junctions and relay towers.

Telegraph repair crews traveled with pole replacement parts and fresh wire, rebuilding damaged lines after attacks.

Keeping the telegraph network intact and operating was crucial.

When wires went dead, uncertainty ruled the day.

Generals were forced to make critical decisions blind to overall strategy. Troop trains were delayed without orders. Morale waned among isolated outposts.

The telegraph made Civil War armies run on time, so cutting the lines introduced chaos.

Severing the enemy's communications was decisive for seizing the upper hand.

TELEGRAPH OPERATORS SOMETIMES LEAKED SENSITIVE MILITARY INFORMATION

The telegraph operators who manned the lines during the Civil War held in their hands immense power—the power to communicate military secrets instantly over vast distances.

While most performed their duties honorably, some abused their positions of trust to leak sensitive information or pull pranks on an epic scale.

This became a source of consternation for generals attempting to maintain operational security.

Young telegraph operators, though sworn to secrecy, were sometimes unable to resist sharing juicy insider knowledge about upcoming battles or campaigns.

Rumors leaked via telegraph had a way of spreading swiftly across the nation.

Opposing forces could gain vital intelligence of plans and troop movements if telegraph operators divulged the contents of classified messages being transmitted.

This loose-lipped tendency compromised more than one surprise attack.

Other operators decided to have mischievous fun with the telegraph using their knowledge of codes and protocols.

Some sent out fake messages ordering troop transfers and supply wagons to imaginary destinations.

Others impersonated generals, sending shocking battle reports and nonsensical directives. While done as pranks, they created organizational havoc and strained relations between commanders.

Frustrated generals threatened serious charges against any operators who continued such unprofessional misconduct.

However, identifying the culprits proved difficult on the busy telegraph circuits spanning states.

Dishonorable operators might put personal enjoyment or profit over duty, not realizing their actions had serious consequences in war. The telegraph's speed enabled both miraculous and unfortunate effects.

GENERAL J.E.B. STUART HAD HIS OWN PERSONAL TELEGRAPH OPERATOR

.webp)

Confederate General J.E.B. Stuart demonstrated how the telegraph could be utilized in innovative ways during the Civil War through his personalized use of the technology.

Stuart, known for his daring cavalry raids and reconnaissance missions behind Union lines, had his own full-time telegraph operator accompany him in the field.

This operator traveled with Stuart's column of raiders, transporting a compact telegraph key set.

At any point during a raid, Stuart could stop near existing telegraph lines, connect his operator to the wires, and tap out messages back to Robert E. Lee's headquarters.

The wires allowed him to transmit updates on his location and intelligence gathered on Union troop dispositions.

In effect, Stuart had a mobile telegraph station enabling him to stay connected across vast distances.

This was a strategic advantage, allowing him to keep his commanders updated while operating deep in enemy territory. No other general on either side went to such measures to integrate instant communications into rapid cavalry movement.

Stuart's maneuverability paired with his telegraph capability allowed him to feed Lee a steady stream of intelligence from behind Union lines.

However, this exposed Lee to disappointment when Stuart's messages inadvertently inflated fears of invasion or the scale of enemy forces spotted. Still, Stuart's telegraph rider demonstrated creative adaptation of new technology.

This pioneering use of field telegraphy foreshadowed modern military communication networks that connect fast-moving armored and aircraft units.

Stuart grasped the telegraph's potential early on, keeping him linked in to headquarters no matter his location.

The "eyes and ears" of Lee's Army of Northern Virginia used the telegraph to maximum effect.

ABRAHAM LINCOLN SOMETIMES WAS DISTRACTED BY TELEGRAPH WIRES

.webp)

President Abraham Lincoln's involvement with the telegraph during the Civil War provides fascinating insights into how he personally directed military affairs.

Lincoln spent innumerable hours in the telegraph room of the War Department adjacent to the White House, obsessively monitoring incoming messages from his generals in the field.

While the telegraph allowed Lincoln an unprecedented connection to his commanders, it also at times distracted him from other important presidential business.

He could become so engrossed reading the latest battlefield telegrams that he neglected meeting with his Cabinet or other officials. Visitors to the White House sometimes had to wait for hours while Lincoln lingered in the telegraph office.

Lincoln's secretaries often had to retrieve the President from the telegraph room to remind him of scheduled obligations.

But as soon as business allowed, Lincoln would hurry back to pore over the tape printouts, scrutinizing troop strengths and movements. If he did not like a general's actions, he would tap out pointed inquiries demanding explanations.

The President's preoccupation with the telegraph was understandable given the monumental stakes of the war. Yet being constantly wired into the latest news from multiple fronts did not always provide clarity.

The onslaught of out-of-context telegrams at all hours could overwhelm Lincoln.

Still, his telegraph fixation speaks to his extremely hands-on approach to managing the war.

The telegraph brought a wartime commander-in-chief into close direct contact with his generals in the field for the first time. But for Lincoln, it became a distraction as well as an advantage.

The technology that helped win the war also consumed his attention, sometimes to a fault.

THE RELIABILITY OF TELEGRAPH LINES DECREASED OVER DISTANCES

While the telegraph dramatically accelerated communications during the Civil War, technical limitations of the early technology sometimes led to confusion and misinformation, especially over long distances.

The primitive telegraph lines were far from perfectly reliable conduits for messages.

The wires themselves were fragile and prone to damage from weather, animals, and sabotage.

Telegraph poles could be felled by storms, while wayward bullets and soldier vandalism also knocked out local lines. Operators had to constantly repair breaks in the wires that left entire stretches of the network useless.

Even intact lines would degrade in signal strength over hundreds of miles.

Weak or disrupted electrical impulses made messages susceptible to errors. Morse code signals became gradually less intelligible the farther they traveled over the wires.

By the time some dispatches reached their destinations from distant battlefields, the contents were so distorted that key facts about unfolding events were missing or misconstrued.

Exact casualty figures, locations, or unit designations could be rendered unrecognizable.

This gave generals and President Lincoln himself an often confused or murky impression of the status of battles based on partial, delayed and error-filled telegrams.

Garbled messages injected potentially disastrous uncertainty into crucial military decision making.

While the telegraph accelerated communications from days or weeks to minutes, technical limitations meant the fog of war was not completely lifted.

The early telegraph networks were imperfect systems, subject to disruptions that eroded information quality over distance. This required recipients to parse intelligence carefully and plan for contingencies arising from miscommunication.

TELEGRAPH MESSAGES WERE ENCRYPTED TO PREVENT THEM FROM BEING READ

The telegraph wires were a rich source of military intelligence if messages could be intercepted.

But both Union and Confederate forces utilized encryption techniques to protect sensitive information transmitted via Morse code. This initiated an era of wartime cryptographic competition.

Tactics included cipher wheels to substitute letters, turning messages into indecipherable jumbles.

Code books assigned number combinations to common phrases for quicker encryption.

However, while these methods provided reasonable security against casual wiretappers, they were far from impenetrable to skilled codebreakers on either side.

Dedicated teams of Union and Confederate telegraphers and signal officers worked intensely to crack intercepted dispatches.

The poorly paid and often young telegraph operators were also enticed into providing stolen code or cipher keys to the enemy.

Their insider knowledge allowed for breakthroughs in decryption.

Once one side achieved the ability to rapidly translate the other's encrypted messages, an intelligence bonanza ensued.

Entire campaign strategies and troop movements were laid bare.

An officer's compromised cipher wheel was a disastrous security breach. However, a new encryption scheme would have to be implemented once the old was broken.

This secret war behind the lines to intercept and decipher military communications foreshadowed modern signals intelligence.

The telegraph accelerated cryptographic innovation while also creating vulnerabilities that could undermine even the most meticulously prepared operations.

Despite the coded trappings of secrecy, little stayed hidden over the Civil War telegraph lines for long.

WOMEN WORKED AS TELEGRAPH OPERATORS DURING THE CIVIL WAR

The telegraph opened up new avenues for women to participate directly in the Civil War.

Several hundred women were employed as telegraph operators, handling vital military communications traffic. Some even operated in close proximity to combat, demonstrating great bravery under fire.

With huge volumes of Morse code messages to be transmitted, the armies urgently needed skilled telegraphers.

Women had proven themselves adept operators, working for commercial telegraph companies before the war.

Their service was now enlisted by necessity.

Female telegraphers were installed at important command centers, relay stations, or alongside generals in the field.

At Manassas and Richmond, women clicked out critical updates as battles raged nearby.

Operators Emma Ellsworth and Bettie Duvall found themselves repeatedly in the crosshairs of fighting.

Working frantically to preserve the flow of wartime information, these women exhibited nerves of steel.

They stayed at their posts amid shelling and infantry clashes, tapping out orders as buildings around them were wrecked.

Their dedication under fire was highly praised.

By managing the military's communications backbone, female telegraphers obtained insights into the war's big picture unlike most other civilians, especially women largely excluded from frontline action.

Their work was historically significant in pioneering women's direct role in American military operations.

While not permitted to formally enlist, these valiant female operators made an undeniably vital contribution.

The telegraph allowed them to leverage specialized skills to aid the war effort on both sides.

They connected presidents to generals, headquarters to armies, nation to battlefield.

Wikipedia - Telegraphy

Britannica - Telegraph

Published On

Last updated.

History News Network puts current events into historical perspective. Subscribe to our newsletter for new perspectives on the ways history continues to resonate in the present. Explore our archive of thousands of original op-eds and curated stories from around the web. Join us to learn more about the past, now.

Sign up for the HNN Newsletter

How the telegraph helped lincoln win the civil war.

©2006 Tom Wheeler

Why the American Civil War Was the First Truly Modern Conflict

- Share on Facebook F

- Share on Twitter L

- Share on LinkedIn I

- Subscribe to RSS R

A plethora of new advances were introduced that changed warfare forever.

Here's What You Need to Know : The American Civil War foreshadowed the industrial era (and European military observers knew it).

It was one of the bloodiest conflicts of the era, and arguably the first “modern war.” It saw a wave of new innovations including modernized warships, the use of aerial observation, more rapid firing small arms and even submarines. If this sounds like the First World War that would be incorrect.

The American Civil War was truly the first modern war and a plethora of new advances were introduced and changed warfare forever.

The Telegraph and Railroad

Prior to the Civil War communications could take days, even weeks to travel only few hundred miles, but that began to change as the telegraph provided vital tactical, operational and strategic communications. Its use has been credited as a contributor to the Union victory. During the war the United States Military Telegraph Service (USMT) handed some 6.5 million messages and laid some 15,000 miles of telegraph lines.

Likewise, the American Civil War was the first conflict in which railroads also provide to be a major factor. In the years leading up to the war, the Northern states laid around 22,000 miles while the South had laid 9,500 miles. The use of railroads on both sides became critically important in transporting men and material.

Iron Ships and Submarines

While the European powers—notably France the United Kingdom—had developed modern naval warships or so-called “ironclads” before the outbreak of the Civil War, it was in the waters off the coast of Virginia where the warships first engaged in combat. After the Civil War, naval warfare never went back to wooden sailing ships and the latter half of the nineteenth-century saw a naval arms race as ships became larger and more heavily armed.

The War Between the States also saw one of the first successful uses of a submarine. The CSN Hunley was essentially an iron tomb for the eight man crew, but it became the first submarine to successfully sink an enemy warship when it was used to successfully deploy a mine on the USS Housatonic .

Rapid Fire Weapons

It is correct that the First World War was the first large scale conflict to see the use of machine guns, but it was the Civil War some fifty years earlier that introduced modern firearms. Muzzle loading firearms gave way to breach-loading repeating rifles, while the Gatling Gun was employed in small numbers.

Fifty years before the Civil War, armies fought with weapons little improved from those employed for well over a century. But fifty years after the Civil War, rapid fire machines changed the concept of war. It was on the terrible and bloody battlefields of conflict that a small arms revolution took place.

Aerial Observation

The American Civil War was fought four decades before the Wright Brothers successfully conducted the first powered flight, but the war is notable for the use of observation balloons , which allowed both sides to monitor enemy troop movements and to direct artillery fire. U.S. Army aviation can also trace its origins back to those hydrogen-filled balloons.

Moreover, both sides had reportedly considered powered flying machines —precursors to the airplane. Nothing came of these efforts, but it is clear that even before the word “airplane” entered in the vernacular forward thinking military planners were already considering how such a weapon could be employed.

Photography

Photographic images of earlier conflicts exist, notably the Crimean War , but it was the American Civil War that is considered to be the first major conflict to be so extensively photographed . Studio owner Mathew Brady is usually credited with most of the photographs taken, but it was Alexander Gardner and his team—working for Brady—who actually took most of the photos.

The use of photographs chronicled the conflict in a way unlike any prior conflict. It allowed a greater understanding of what it was actually like in the field. While painters still traveled along with the armies, few paintings of any battle had shown the bloated corpses or the other horrors of war that photographs provided.

Peter Suciu is a Michigan-based writer who has contributed to more than four dozen magazines, newspapers and websites. He regularly writes about military small arms, and is the author of several books on military headgear including A Gallery of Military Headdress , which is available on Amazon.com .

This article first appeared in February 2021.

Image: Wikimedia Commons

Search The Lehrman Institute Sites:

- Mr. Lincoln and Observers

- Lincoln at Washington

- Meeting Mr. Lincoln

- Non Public Areas

- Grounds and Entrance

- Changes in the White House

- The War Effort

- Other Government Buildings

- Parks and Pennsylvania Avenue

- Hotels and Other Public Buildings

- Relatives and Residents

- Cabinet and Vice Presidents

- Congressmen

- Generals and Admirals

- Notable Visitors

- Mary’s Charlatans

- Employees and Staff

- Abraham Lincoln’s Classroom

- Mr. Lincoln and the Founders

- Mr. Lincoln and Freedom

- Mr. Lincoln and New York

- Mr. Lincoln and Friends

- Lincoln & Churchill

- Abraham Lincoln and the Civil War Blog

- AbrahamLincoln.org

- Lincoln at Peoria

- The Lehrman Institute

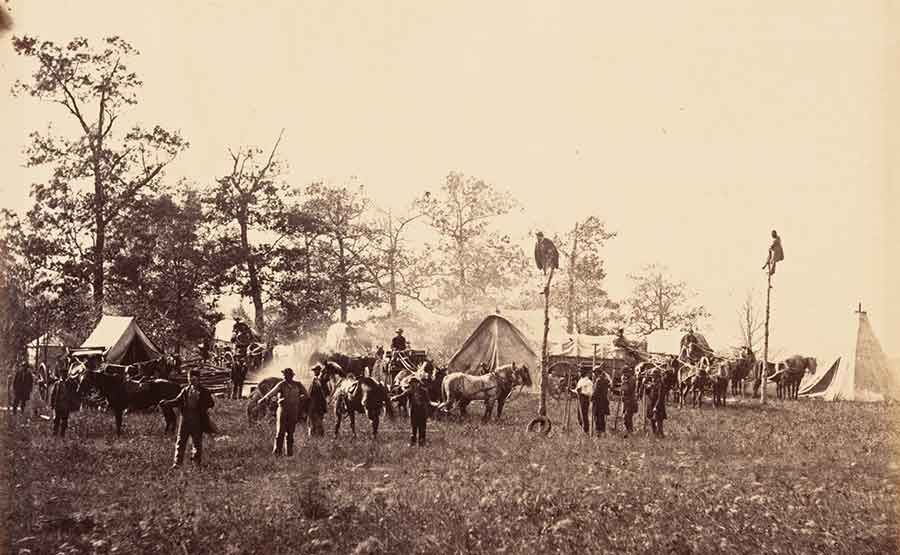

The War Effort: Telegraph Office

In March 1862 Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton insisted in centralizing all telegraph communication for the war at the War Department’s old library next to his office. The President therefore had to go to the telegraph office there to read war despatches and send his own. (The telegraph office had previously been located in two other locations in the same building, but General George McClellan had his own telegraph service at his headquarters in 1861-1862.) The office gave Mr. Lincoln an opportunity to write and think in peace as he waited for telegrams to arrive and be deciphered – as well to socialize in a way that was impossible elsewhere in Washington. Telegraph operator Albert B. Chandler reported the President said: “I come here to escape my persecutors. Hundreds of people come in and say they want to see me for only a minute. That means if I can hear their story and great their request in a minute, it will be enough.” 1 One telegraph operator, Homer Bates, later recorded Mr. Lincoln’s routine:

When in the telegraph office, Lincoln was most easy of access. He often talked with the cipher-operators, asking questions regarding the despatches which we were translating from or into cipher, or which were filed in the order of receipt in the little drawer in our cipher-desk. Lincoln’s habit was to go immediately to the drawer each time he came into our room, and read over the telegrams, beginning at the top, until he came to the one he had seen at his last previous visit. When this point was reached he almost always said, “Well, boys, I am down to raisins.” After we had heard this curious remark a number of times, one of us ventured to ask him what it meant. He thereupon told us the story of the little girl who celebrated her birthday by eating very freely of many good things, topping off with raisins for desert. During the night she was taken violently ill, and when the doctor arrived she was busy casting up her accounts. The genial doctor, scrutinizing the contents of the vessel, noticed some small black objects that had just appeared, and remarked to the anxious parent that all danger was past, as the child was ‘down to raisins.’ ‘So,’ Lincoln said, ‘when I reach the message in this pile which I saw on my last visit, I know that I need go no further.” 2

Early in the Civil War, President Lincoln’s visits to the War Department and the Winder Building could pass virtually without notice. Just before the First Battle of Bull Run, Benjamin Brown French recorded in his diary: “I staid about the War Department perhaps an hour, saw President Lincoln pass through the lower passage, which was crowded with people. He was dressed in a common linen coat, had on a straw hat, & pushed along through the crowd without looking to the right or left, and no one seemed to know who he was. He entered the East door, passed entirely through & out at the West door, & across the street to Gen. Scott’s quarters. I was somewhat amused to see with what earnestness he pushed his way along & to observe his exceedingly ordinary appearance.” 3

On his nocturnal walks to the War Department, Mr. Lincoln was sometimes accompanied by a secretary or friend. When he went alone, he was supposed to carry a stick as protection — and to assuage the worries of his wife. 4 Once he arrived, his usual routine at the War Department was reported by Major Thomas J. Eckert – a routine which led to the completion of the first draft of the Emancipation Proclamation:

“As you know, the President came to the office every day and invariably sat at my desk while there. Upon his arrival early one morning in June, 1862, shortly after McClellan’s ‘Seven Days’ Fight,’ he asked me for some paper, as he wanted to write something special. I procured some foolscap and handed it to him. He then sat down and began to write. I do not recall whether the sheets were loose or had been made into a pad. There must have been at least a quire. He would look out of the window a while and then put his pen to paper, but he did not write much at once. He would study between times and when he had made up his mind he would put down a line or two, and then sit quiet for a few minutes. After a time he would resume his writing, only to stop again at intervals to make some remark to me or to one of the cipher operators as a fresh despatch from the front was handed to him. “Once his eye was arrested by the sight of a large spider-web stretched from the lintel of the portico to the side of the outer window-sill. This spider-web was an institution of the cipher-room and harbored a large colony of exceptionally big ones. We frequently watched their antics, and Assistant Secretary Watson dubbed them “Major Eckert’s lieutenants.” Lincoln commented on the web, and I told him that my lieutenants would soon report and pay their respects to the President. Not long after a big spider appeared at the cross-roads and tapped several times on the strands, whereupon five or six others came out from different directions. Then what seemed to be a great confab took place, after which they separated, each on a different strand of the web. Lincoln was much interested in the performance and thereafter, while working at the desk, would often watch for the appearance of his visitors. “On the first day Lincoln did not cover one sheet of his special writing paper (nor indeed on any subsequent day). When ready to leave, he asked me to take charge of what he had written and not allow any one to see it. I told him I would do this with pleasure and would not read it myself. ‘Well,’ he said, ‘I should be glad to know that no one will see it, although there is no objection to your looking at it; but please keep it locked up until I call for it to-morrow.’ I said his wishes would be strictly complied with. “When he came to the office on the following day he asked for the papers, and I unlocked my desk and handed them to him and he again sat down to write. This he did nearly every day for several weeks, always handing me what he had written when ready to leave the office each day. Sometimes he would not write more than a line or two, and once I observed that he had put question-marks on the margin of what he had written. He would read over each day all the matter he had previously written and revise it, studying carefully each sentence. “On one occasion he took the papers away with him, but he brought them back a day or two later. I became much interested in the matter and was impressed with the idea that he was engaged upon something of great importance, but did not know what it was until he had finished the document and then for the first time he told me that he had been writing an order giving freedom to the slaves in the South, for the purpose of hastening the end of the war. He said he had been able to work at my desk more quietly and command his thoughts better than at the White House, where he was frequently interrupted. I still have in my possession the ink-stand which he used at that time and which, as you know, stood on my desk until after Lee’s surrender. The pen he used was a small barrel-pen by Gillott-such as were supplied to the cipher-operators.” 5

Another army officer, Major A.E.H. Johnson, recalled: “He came over from the White House several times a day, and, thrusting his long arm down among the messages fished them out one by one and read them. When he had secured the last one he invariably made some characteristic remark – generally something that caused laughter – and then proceeded to consult with Secretary Stanton.” 6 Earlier in the war, Secretary Stanton had barred even the President from seeing telegrams from the front. One dispatch never reached either Stanton or Mr. Lincoln although it was received in the telegraph office. At the conclusion of the Seven days Battles in July 1862, General McClellan telegraphed: “If I save this Army I tell you plainly that I owe no thanks to you or any other persons in Washington – you have done your best to sacrifice this Army.” The statement scandalized Colonel Edward S. Sanford and he censored the line before the rest of the telegram was given to Stanton. 7

On July 5, 1865, the operators learned of the capture of Vicksburg by General Ulysses S. Grant. Although strict rules prohibited their consumption of liquor while on duty, they decided to celebrate the victory and mitigate the city’s heat wave by ordered up a can of bear. “We were passing the bucket around when, to our astonishment and alarm, in strode the President, who had to come to look over our despatches at first hand. You can imagine our embarrassment,” recalled head telegraph operator Edward Rosewater. “We had been caught by the Chief Executive. He had seen the tell-tale can, and although this was now practically empty, Lincoln was too shrewd a man not to know that were all guilty of violating one of the strictest orders of the War Department. But he affected at first not to notice. Coming over to my instrument he asked to see the latest despatch. He read it slowly, handed it back, and, turning to the messenger, who had been hoping for a favorable moment to make his escape with the can, Lincoln asked: ‘What have you in that bucket?'” Once Rosewater made the appropriate confessions, the President ordered the messenger to go get more beer and provided the twenty-five cent coin to do so. When the beer was delivered, the President declined the offer of a glass and picked up the bucket to take a drink while stilling holding Grant’s victory telegram.” 8

Although the President was permitted to walk alone to the War Department at night, his return to the White House was usually with an army guard, according to Henry W. Knight, a convalescing soldier who participated in such duties. “I seem to see him now, as – his tall, ungainly form wrapped in an old gray shawl, wearing usually a ‘shockingly bad hat,’ and carrying a worse umbrella – he came up the steps into the building,” wrote Knight three decades later. “When Mr. Lincoln was ready to return we would take up a position near him, and accompany him safely to the White House. I presume I performed this duty fifty times. On the way to the White House, Mr. Lincoln would converse with us on various topics. I remember one night when it was raining very hard that he came over, and about one o’clock he started back. As he saw us at the door, ready to escort him, he addressed us in these words: ‘Don’t come out in the storm with me tonight, boys. I have my umbrella, and can get home safely without you.’ ‘But,’ I replied, ‘Mr. President, we have positive orders from Mr. Stanton not to allow you to return alone; and you know we dare not disobey his orders.’ ‘No,’ replied Mr. Lincoln, ‘I suppose not; for if Stanton should learn that you had let me return alone, he would have you court-martialed and shot inside of twenty-four hours.” 9

Sometimes, the President was accompanied by an aide on these rambles. According to Lincoln’s Assistant Secretary, John Hay, writing his diary on September 1, 1862: “This morning I walked with the President over to the War Department to ascertain the truth of the report that Jackson had crossed the Potomac. We went to the telegraph office and found it true. On the way over the President said, “McClellan is working like a beaver. He seems to be aroused to doing something, by the sort of snubbing he got last week. I am of the opinion that this public feeling against him will make it expedient to take important command from him. The Cabinet yesterday were unanimous against him. They were all ready to denounce me for it, except Blair. He has acted badly in this matter, but we must use what tools we have. There is no man in the Army who can man these fortifications and lick these troops of ours into shape half as well as he.’ I spoke of the general feeling against McClellan as evinced by the Prests mail. He rejoined, “Unquestionably he has acted badly toward Pope! He wanted him to fail. That is unpardonable, but he is too useful just now to sacrifice.’ At another time he said of McClellan, ‘If he can’t fight himself, he excels in making others ready to fight.'” 10

Two years later, Hay wrote in a letter on October 11, 1864: “At eight o’clock the President went over to the War Department to watch for despatches. I went with him. We found the building in a state of preparation for siege. Stanton had locked the doors and taken the keys upstairs, so that it was impossible even to send a card to him. A shivering messenger was pacing to and fro in the moonlight over the withered leaves, who, catching sight of the President, took us around by the Navy Department & conducted us into the War Office by a side door.” 11

On Election Night on November 8, 1864, the War Department’s telegraph office gave President Lincoln an opportunity to learn the latest election returns, starting shortly after 7 P.M. By the time his election had been assured several hours later, the President had been employed in dispensing fried oysters. Journalist Noah Brooks reported that night’s events:

“Election day was dull, gloomy and rainy; and, as if by common consent, the White House was deserted, only two members [Gideon Welles and Edward Bates] of the Cabinet attending the regular meeting of that body….The President took no pains to conceal his anxious interest in the result of the election then going on all over the country, but just before the hour for Cabinet meeting he said: ‘I am just enough of a politician to know that there was not much doubt about the result of the Baltimore Convention, but about this thing I am far from being certain; I wish I were certain.’ Very few Union men here would have been unwilling to be as certain of a great good for themselves as they were of Lincoln’s re-election. The first gun came from Indiana, Indianapolis sending word about half-past six in the evening that a gain of fifteen hundred in that city had been made for Lincoln. At seven o’clock, accompanied only by a friend, the President went over the War Department to hear the telegraphic dispatches, as they brought in the returns, but it was nearly nine o’clock before anything definite came in, and then Baltimore sent up her splendid majority of ten thousand plus. The President only smiled good-naturedly and said that was a fair beginning. Next Massachusetts send word that she was good for 75,000 majority (since much increased), and hard upon her came glorious old Pennsylvania, [John W. Forney] telegraphing that the State was sure for Lincoln. ‘As goes Pennsylvania, so goes the Union, they say,’ remarked Father Abraham, and he looked solemn, as he seemed to see another term of office looming before him. There was a long lull, and nothing heard from New York, the chosen battle ground of the Democracy, about which all were so anxious. New Jersey broke the calm by announcing a gain of one Congressman for the Union, but with a fair prospect of the State going for McClellan; then the President had to tell a story about the successful New Jersey Union Congressman, Dr. Newell, a family friend of the Lincolns, which was interrupted by a dispatch from New York City, claiming the State by 10,000. ‘I don’t believe that,’ remarked the incredulous Chief Magistrate, and when Greeley telegraphed at midnight that we should have the state by about four thousand, he thought that more reasonable. So the night wore on, and by midnight we were sure of Pennsylvania, the New England States, Maryland, Ohio, Indiana, Michigan, Wisconsin, and it then appeared that we should have Delaware. Still no word came from Illinois, or Iowa, or any of the trans-Mississippi States, and the President was specially concerned to hear from his own State, which sent a despatch from Chicago about one o’clock in the morning, claiming the State for Lincoln by 20,000 and Chicago by 2,500 majority. The wires worked badly on account of the storm, which increased, and nothing more was heard from the West until last night, the 10th, when the President received two days’ despatches from Springfield, claiming the state by 17,000 and the Capital by 20 majority, Springfield having been heretofore Democratic. By midnight the few gentlemen in the office had had the pleasure of congratulating the President on his re-election. He took it very calmly – said that he was free to confess that he felt relieved of suspense, and was glad that the verdict of the people was so likely to be clear, full and unmistakable, for it them appeared that his majority in the electoral college would be immense. About two o’clock in the morning a messenger came over from the White House with the intelligence that a crowd of Pennsylvanians were serenading his empty chamber, whereupon he went home, and in answer to repeated calls came forward and made one of the happiest and noblest little speeches of his life…” 12

John Hay’s recollections of Election Night on November 8, 1864 were more extensive than his notes on the October elections:

Eckert came in shaking the rain from his cloak, with trousers very disreputably muddy. We sternly demanded an explanation. He had slipped, he said, & tumbled prone, crossing the street. He had done it, watching a fellow-being ahead and chuckling at his uncertain footing. Which reminded the Tycoon, of course. The President said, ‘For such an awkward fellow, I am pretty sure-footed. It used to take a pretty dextrous man to throw me. I remember, the evening of the day in 1858, that decided the contest for the Senate between Mr Douglas and myself, was something like this, dark, rainy & gloomy. I had been reading the returns, and had ascertained that we had lost the Legislature and started to go home. The path had been worn hog-back was slippery. My foot slipped from under me, knocking the other one out of the way, but I recovered myself & lit square, and I said to myself, ‘It’s a slip and not a fall.’ The President sent over the first fruits to Mrs. Lincoln. He said, ‘She is more anxious than I.’ We went into the Secretary’s room. Mr [Gideon] Wells and [Assistant Navy Secretary Gustavus] Fox soon came in. They were especially happy over the election of Rice, regarding it as a great triumph for the Navy Department. Says Fox, ‘There are two fellows that have been especially malignant to us, and retribution has come upon them both, [John P.Hale] and [HenryWinter Davis].’ ‘You have more of that feeling of personal resentment than I,’ said Lincoln. ‘Perhaps I may have too little of it, but I never thought it paid. A man has not time to spend half his life in quarrels. If any man ceases to attack me, I never remember the past against him. It has seemed to me recently that [Henry Winter Davis] was growing more sensible to his own true interests and has ceased wasting his time by attacking me. I hope for his own good he has. He has been very malicious against me but has only injured himself by it. His conduct has been very strange to me. I came here, his friend, wishing to continue so. I had heard nothing but good of him; he was the cousin of my intimate friend Judge [David Davis]. But he had scarcely been elected when I began to learn of his attacking me on all possible occasions. It is very much the same with Hickman. I was much disappointed that he failed to be my friend. But my greatest disappointment of all has been with Grimes. Before I came here, I certainly expected to rely upon Grimes more than any other one man in the Senate. I like him very much. He is a great strong fellow. He is a valuable friend, a dangerous enemy. He carries too many guns not to be respected in any point of view. But he got wrong against me, I do not clearly know how, and has always been cool and almost hostile to me. I am glad he has always been the friend of the Navy and generally of the Administration. Despatches kept coming in all the evening showing a splendid triumph in Indiana, showing steady, small gains all over Pennsylvania, enough to give a fair majority this time on the home vote. Guesses from New York and Albany which boiled down to about the estimated majority against us in the city, 35,000, and left the result in the State still doubtful. A despatch from [General Benjamin] Butler was picked up & sent by [Major General C.W.] Sanford, saying that the City had gone 35,000 McC. & the State 40,000. This looked impossible. The State had been carefully canvassed & such a result was impossible except in view of some monstrous and undreamed of frauds. After a while another came from Sanford correcting former one & giving us the 40,000 in the State. Sanford’s despatches all the evening continued most jubilant: especially when he announced the most startling majority of 80,000 in Massachusetts. “General Eaton came in and waited for news with us. I had not before known he was with us. His denunciations of [Horatio] Seymour were especially hearty and vigorous. Towards midnight we had supper, provided by Eckert. The President went awkwardly and hospitably to work shovelling out the fried oysters. He was most agreeable and genial all the evening in fact. Fox was abusing the coffee for being so hot–saying quaintly, it kept hot all the way down to the bottom of the cup as a piece of ice staid cold till you finished eating it. We got later in the evening a scattering despatch from the West, giving us Michigan, one from Fox promising Missouri certainly, but a loss of the first district from that miserable split of Knox & Johnson, one promising Delaware, and one, too good for ready credence, saying Raymond & Doge & Darling had been elected in New York City. Capt Thomas came up with a band about half-past two, and made some music and a small hifalute. The President answered from the window with rather unusual dignity and effect & we came home. 13

According to Hay, “The President in a lull of despatches took from his pocket the Nasby Papers and read several chapters of the experience of the saint & martyr, Petroleum V. They were immensely amusing, Stanton and Dana enjoyed them scarcely less than the President, who read, con amore, until 9 o’clock.” 14 Dana later recalled that Stanton’s real reaction was quite negative, calling Dana aside, cursing and complaining, “Here is the fate of this whole republic at stake, and here is the man around whom it all centers, on whom it all depends, turning aside from this monumental issue to read the God damned trash of a silly mountebank!” 15

Six months later on April 3, 1865, a presidential telegram “From Richmond” sent War Department telegraph operators to the windows to shout “Richmond has fallen!” – spreading the news across Washington. “In four minutes there were thousands of people around the Department,” reported the 16-year-old youth who took down the telegram. “The streets filled from every direction. Horse cars had no show; steam fire-engines came out on the avenue, bunched themselves, and commenced whistling; cannon planted in the park close by began firing; and men, women, and children yelled themselves hoarse and acted ridiculous.” 16

Ten days later, President Lincoln visited the War Department before he went to the theater. He had been unable to prevail on either Edwin Stanton or Ulysses S. Grant to go to Ford’s Theater with Mrs. Lincoln and their wives. Grant had initially agreed to go but his wife convinced him to reconsider because her last experience with Mrs. Lincoln had been highly unpleasant. Telegraph operator Homer Bates later recorded the events of the President’s last day of life:

On the morning of the 14th, Lincoln made his usual visit to the War Department and told Stanton that Grant had cancelled his engagement for that evening. The stern and cautious Secretary again urged the President to give up the theater-party, and, when he found he was set on going, told him he ought to have a competent guard. Lincoln said: “Stanton, do you know that Eckert can break a poker over his arm?” Stanton, not knowing what was coming, looked around in surprise and answered, “No, why do you ask such a question?” Lincoln said: “Well, Stanton, I have seen Eckert break five pokers, one after the other, over his arm, and I am thinking he would be the kind of man to go with me this evening. May I take him?” Stanton, still unwilling to encourage the theater project, said that he had some important work for Eckert that evening, and could not spare him. Lincoln replied: “Well, I will ask the Major myself, and he can do your work tomorrow.” He then went into the cipher-room, told Eckert of his plans for the evening, and said he wanted him to be one of the party, but that Stanton said he could not spare him. “Now, Major,” he added, “come along. You can do Stanton’s work to-morrow, and Mrs. Lincoln and I want you with us.” Eckert thanked the President but, knowing Stanton’s views, and that Grant had been induced to decline, [said] to the President he could not accept because the work which the Secretary referred to must be done that evening, and could not be put off. “Very well,” Lincoln then said, “I shall take Major [Henry] Rathbone along, because Stanton insists upon having some one to protect me; but I should much rather have you, Major, since I know you can break a poker over your arm.” 17

- Don E. Fehrenbacher and Virginia Fehrenbacher, editors, Recollected Words of Abraham Lincoln , p. 93.

- David Homer Bates, Lincoln in the Telegraph Office , p. 41.

- Benjamin Brown French, Witness to the Young Republic , p. 365.

- Helen Nicolay, Lincoln’s Secretary , p. 121.

- Bates, Lincoln in the Telegraph Office , pp. 138-141.

- Frank A. Flower, Edwin McMasters Stanton , p. 217.

- Stephen W. Sears, To the Gates of Richmond , p. 251.

- Rufus Rockwell Wilson, editor, Intimate Memories of Lincoln , p. 576.

- Harold Holzer, Lincoln as I Knew Him , p. 218.

- Tyler Dennett, editor, Lincoln and the Civil War in the Diaries and Letters of John Hay , p. 47.

- Michael Burlingame and John R. Turner Ettlinger, editors, Inside Lincoln’s White House: The Complete Civil War Diary of John Hay .

- Michael Burlingame, editor, Lincoln Observed: Civil War Dispatches of Noah Brooks , pp. 143-144.

- Burlingame and Ettlinger, editors, Inside Lincoln’s White House: The Complete Civil War Diary of John Hay , p. 246.

- Burlingame and Ettlinger, editors, Inside Lincoln’s White House: The Complete Civil War Diary of John Hay , p. 38.

- Benjamin P. Thomas and Harold M. Hyman, Stanton: The Life and Times of Lincoln’s Secretary of War , p. 330.

- Frank A. Flower, Edwin McMasters Stanton , p. 262.

- Bates, Lincoln in the Telegraph Office , p. 366-368.

- Mr. Lincoln

- White House

- Residents & Visitors

The Lehrman Institute Web Sites

© 2002-2024 The Lehrman Institute. All rights reserved. Founded by The Lehrman Institute.

The Civil War

A Smithsonian magazine special report

How Newspapers Reported the Civil War

A collection of historic front pages shows how civilians experienced and read about the war

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Civil-War-headlines-Illustrated-News-631.jpg)

Chester County Times

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Civil-War-headlines-Chester-County-Times-1.jpg)

The Chester County Times in Pennsylvania made no attempt to disguise how it felt about the election of Abraham Lincoln as the nation’s 16th president. “A Clean Sweep!” it exclaimed. “Corruption Ended!! The Country Redeemed! Secession is Rebuked!!! Let the Traitors Rave!”

This was a time when newspapers were rigidly aligned with political parties. In Chester County, Lincoln’s win signaled a chance to lay on the exclamation marks. It was also a time when news-hungry citizens relied on newspapers as the primary means of mass communication. Advances in technology—especially the development of the telegraph—made rapid dissemination of the news possible. The Twitter of the era, the telegraph cut days or weeks off the time it took dispatches to reach the public.

The Chester County Times is one of more than 30 newspapers spotlighted in “ Blood and Ink: Front Pages From the Civil War ” at the Newseum in Washington, D.C. The show, which coincides with the sesquicentennial of the Civil War and runs through 2012, covers key events of the war, including major battles and the lead-up to and resolution of the conflict, says curator Carrie Christoffersen.

Published November 7, 1860, the Times ’ election extra reported Lincoln had won Pennsylvania, New York, Ohio, Indiana and Rhode Island. (In the end, Lincoln carried every Northern state except New Jersey.) Virginia went for candidate John Bell, and North Carolina for John C. Breckinridge. The front page uses the abbreviation “Breck’ge, credits the telegraph operator by name and fills the final column with the cryptic, boldface words “Wide Awake.”

Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Civil-War-headlines-Frank-Leslies-Illustrated-Newspaper-2.jpg)

Lincoln’s election was the final trigger for secession, and Jefferson Davis became president of the Confederate States of America. Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper , based in New York City, printed a woodblock engraving of Davis addressing the citizens of Montgomery, Alabama, from the balcony of the Exchange Hotel on February 16, 1861, two days before his inauguration. The illustrator depicted men waving their top hats in jubilation on the ground, while overhead, two other men, presumably slaves, perched on narrow pedestals and held candlesticks to cast light on Davis’ face.

Illustrated News

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Civil-War-headlines-Illustrated-News-3.jpg)

Soon artists and correspondents were covering far more dangerous assignments. Calling themselves the “Bohemian Brigade,” they traveled with armies as witnesses to war. “There were battlefield sketch artists who were essentially embedded,” says Christoffersen. These men were dubbed “specials.” When Confederate shots erupted in Charleston Harbor, South Carolina, on April 12, 1861, a special positioned himself near U.S. Army Maj. Robert Anderson on the rampart of Fort Sumter. The scene he drew graced page 1 of the New York Illustrated News on April 20. (War scenes usually took about two weeks to appear in print.) The accompanying article described a “gallant Major as he vainly scanned the horizon for the expected supplies and reinforcements, upon which depended the continued occupation of the fortress, but which, alas, he was never destined to receive.” Union forces surrendered after 34 hours.

Although newspapers weren’t yet able to reproduce photographs, says Christoffersen, they could use information documented in photographs to make engravings. The Illustrated News points out that its portrait of Anderson was sketched from a photo taken at the fort.

The British Workman

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Civil-War-headlines-British-Workman-4.jpg)

Even foreign publications of the time were partisan in their war coverage. In November 1861, the British Workman , a monthly, published an engraving of a slave auction peopled with animated bidders and frightened slaves. In the top corner is written “Registered for Transmission Aboard” indicating the periodical was intended for American eyes.

Cleveland Plain Dealer

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Civil-War-headlines-Cleveland-Plain-Dealer-5.jpg)

On December 24, 1861, the Cleveland Plain Dealer published a political cartoon on its front page. “The Confederate Government in Motion” shows a rolling crocodile labeled “Davis’s Great Moving Circus” carrying five seated men. “Satire was big at this stage,” says Christoffersen. “The implication of this cartoon seems to be that the Confederacy was on the run.” In truth, it had relocated its capital from Montgomery, Alabama, to Richmond, not to Nashville.

(Southern cartoonists took jabs at the North as well. The National Portrait Gallery is displaying rare caricatures of Lincoln by Adalbert J. Volck of Baltimore through January 21, 2013.)

The Confederate State

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Civil-War-headlines-The-Confederate-State-6.jpg)

As the war progressed, newsprint grew scarce in the South because of a Union Navy blockade. The Newseum exhibit features two Confederate newspapers that were printed on wallpaper that was still available, using the blank reverse side. The Confederate State , which looks blotchy because the wallpaper pattern shows through from the back, was published in New Iberia, Parish of St. Martin, Louisiana on September 20, 1862. Its motto was a quotation of Davis: “Resistance to Tyrants in Obedience to God.” Stars and Stripes published in Jacksonport, Arkansas, printed its December 1, 1863, issue with a vivid wallpaper border showing alongside the front page.

Harpers Weekly

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Civil-War-headlines-Harpers-Weekly-7.jpg)

The popular Harper’s Weekly , based in New York, was pro-Union, as can be seen in a June 18, 1864, illustration of emaciated prisoners of war. The caption read: “Rebel cruelty—our starved soldiers. From photographs taken at United States General Hospital, Annapolis, Maryland.” The men had been released from Belle Isle camp, in the James River in Richmond, and later died.

The Press in the Field

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Civil-War-headlines-The-Press-in-the-Field-8.jpg)

Mid-war, in 1862, sketch artist Thomas Nast joined Harper’s , which was selling for the war-inflated price of six cents an issue. Nast, who later gained fame for his bold caricatures of such politicians as Boss Tweed, drew an elaborate two-page triptych, “The Press in the Field,” published April 30, 1864. The center panel shows a correspondent on horseback talking to soldiers back from battle. A bearded man (possibly Nast himself) sits atop the left panel holding a sketchpad. Below him a correspondent interviews emancipated slaves while an artist records the scene. At right the correspondent interviews another man.

The Philadelphia Inquirer

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Civil-War-headlines-The-Philadelphia-Inquirer-9.jpg)

Newspapers provided elaborate coverage of Lincoln’s assassination and funeral. On April 15, 1865, the Evening Express in Washington published an extra that reported his death at “half-past 7 this morning”; a black border surrounds the news columns. Ten days later, the Philadelphia Inquirer printed images of Lincoln’s casket in Independence Hall and the interior of the railroad car that transported his body.

Christoffersen said museum-goers often are surprised that the papers are 150-year-old originals. During the mid-1800s, newspapers had a high rag content, which meant they didn’t decay as much as papers with more wood content a few decades later.

Get the latest History stories in your inbox?

Click to visit our Privacy Statement .

open search

- Closed Today

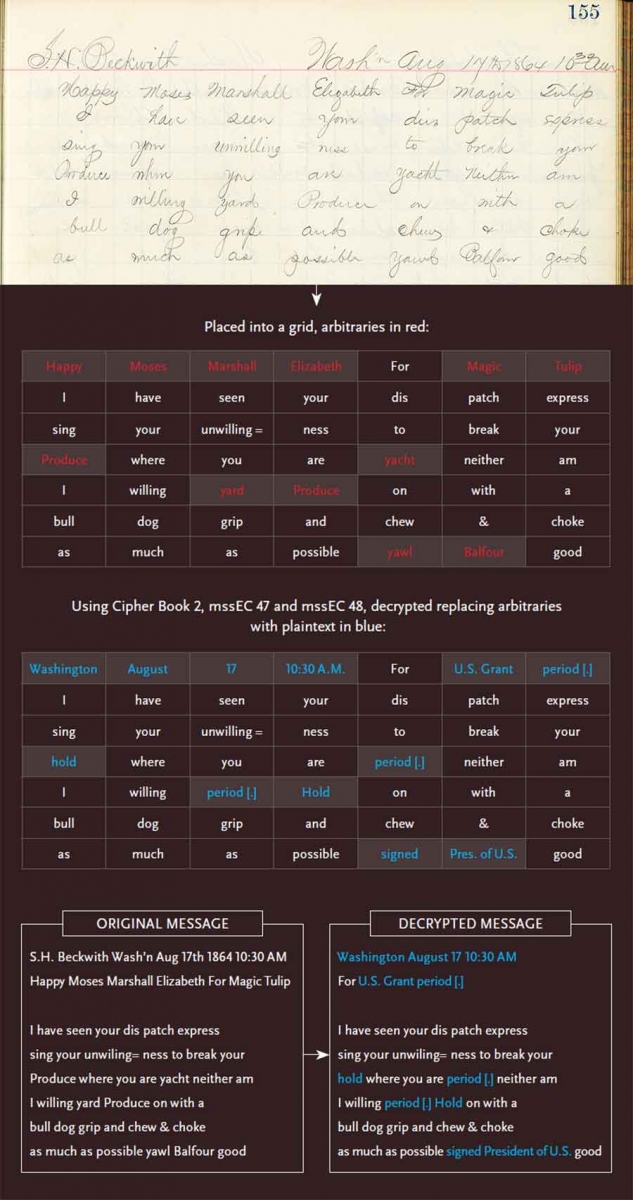

Archiving the Civil War’s Text Messages

A massive crowdsourcing project is digitizing thousands of coded union telegrams.

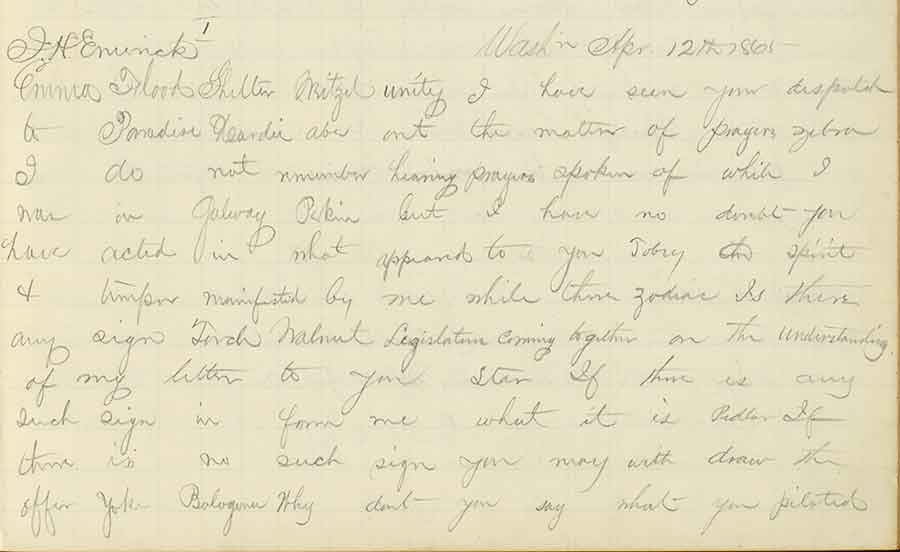

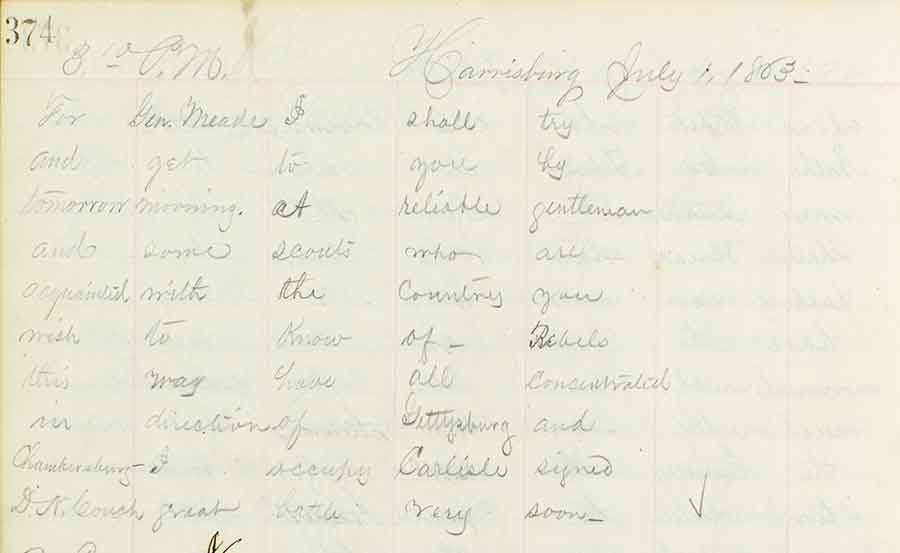

To gain insights into the U.S. Civil War, The Huntington launched an innovative crowdsourcing project last year to transcribe and decipher a collection of telegrams between Abraham Lincoln, his Cabinet, and officers of the Union Army. Roughly one-third of the messages are written in code.

In the first phase of the project, called “Decoding the Civil War,” volunteers have worked online to provide transcriptions of the telegrams, creating an extraordinarily rich database. In a second phase, volunteers will comb this database to identify significant people, dates, and times, enabling the creation of a robust search function. In the final phase, code books in the archive will be used to decipher the encoded telegrams, potentially providing insights into the history of the Civil War.

In what follows, Daniel Lewis, Dibner Senior Curator of the History of Science and Technology at The Huntington, provides his take on the importance and relevance of the project.

The Thomas T. Eckert Papers—consisting of records, ledgers, and cipher books kept by the head of the War Department’s military telegraph office—came to us at The Huntington four years ago via a long and winding road. The collection includes nearly 16,000 telegrams reporting on the U.S. Civil War as it happened, and they are already beginning to tell scholars astonishing things.

The Eckert Papers initially were sold at a private auction in 2009. The sellers were apparently descendants of Eckert’s, and the auction sale was a surprise, because the papers were thought to have been destroyed after the Civil War. In 2012, a documents dealer in White Plains, N.Y., offered the collection to The Huntington.

When the collection arrived at The Huntington, we decided that it could benefit from a collaborative effort to digitize and transcribe the telegraphs, and in turn the materials could offer valuable teaching tools for the classroom. To that end, The Huntington, the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum, North Carolina State University, and Zooniverse (a non-profit devoted to citizen science) applied for a grant from the National Archives’ National Historical Publications and Records Commission to make the telegraphs more usable and discoverable. We also hoped to model collaboration among libraries, museums, social studies education departments, and private software companies.

This joint effort has let us engage new and younger audiences by enlisting their service as “citizen archivists” to help digitize the telegrams. The crowdsourcing component run by Zooniverse enabled us to recruit more than 4,600 interested individuals to transcribe the telegrams with greater efficiency and accuracy than could be done by staff at participating museums. The project is also designed to build digital literacy, critical thinking skills, and research proficiency, with activities that can be used for many years by classroom teachers and museum educators.

Beyond the historical value these documents carry, their most surprising revelation may be the striking resemblance they bear to today’s tweets, emails, and text messages. Most telegrams were written for brevity and tapped out in Morse code: shorthand communiques, queries, and commands. A great number of the telegrams were coded and proved impossible to crack. They offered the Union almost-instant intelligence about the war and its sweeping, rotating, and seemingly erratic movements and strategies.

The Civil War’s great, fiery, hour-by-hour drama was played out in hundreds of these dispatches, and things needed doing quickly. Some of the telegrams are riveting in their terseness. “Chattanooga Dec. 6 ’63,” one began. “For Gen Halleck—Dispatch just read from Gen Foster indicates beyond doubt that Longstreet is retreating towards Virginia I have directed him to be well followed up sig US Grant 4:30 PM.” Those 32 words were issued by Ulysses S. Grant, who was just weeks from becoming the Commander of the Union Army.

People of all ranks sent messages through the telegraph offices. Soft-spoken Abraham Lincoln was an articulate and eloquent spokesman for his causes, even as brevity was one of his hallmarks: The Gettysburg Address is only 272 words long, after all. The White House was close to the telegraph quarters—making the medium perfectly suited as a communications device for our 16th president. “I have seen your dispatch expressing your unwillingness to break your hold where you are. Neither am I willing. Hold on with a bulldog grip, and chew & choke as much as possible,” Lincoln wrote—dare we say texted?—to Grant, by then the Commanding Officer of the Union Army, just months prior to the 1864 presidential election.

Sometimes telegraph operators helped soldiers and officers transmit personal messages. “A. Lincoln Telegraph lines have been down all day,” one transmission from December of 1862 began. “In a day or two our dead are all buried & the wounded are being well cared for the whole Army is in good condition but our loss will much exceed the figures I first named to you will probably reach ten thousand.” The author, “A.E. Burnside,” then noted that he’d sent a couple of dispatches to his wife earlier in the day, “which I hope you will allow to go through as they are very important to me personally.” This writer, of course, was Ambrose E. Burnside, Lincoln’s commander of the Army of the Potomac. Just three days earlier, Burnside had led the Union Army into the disastrous Battle of Fredericksburg, after considerable prodding from Lincoln. Things were tense, and the note is from a man whose reputation and whose troops had been badly diminished at the hands of the president.

Much like modern emails, the telegrams, stripped of almost all formality, were sometimes emotional but right to the point. In the middle of an October 4, 1863, report to General Halleck, William T. Sherman mentioned, “My eldest boy Willie, my California boy, nine years old, died here yesterday of fever and dysentery contracted at Vicksburg. His loss to me is more than words can express but I would not let it direct my mind from the duty I owe the Country.” Sherman then returned to his troops on the move, stoically carrying on with his patriotic duty to the Union cause.

These are the kinds of contexts, and subtexts, that appear regularly in the telegrams. The war wasn’t fought on paper or via telegraph lines. It was waged in combat, with blood and indecision and in sorrow—and occasionally, with joy—but almost always with resolute strength. But like modern-day iPhone jockeys, the senders and recipients of these 19th-century tweets, and the operators who kept it all working, understood the immediacy of the telegram and the value of instant communication: the things it could do to advance the cause of the war, direct strategic maneuvers, and, sometimes, ease pain.

This story originally appeared in Zócalo Public Square and was republished in Slate.

People interested in participating in the “Decoding the Civil War” project can go to its website .

Daniel Lewis is Dibner Senior Curator of the History of Science and Technology at The Huntington.

QUICK LINKS

- Plan Your Visit

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Civil War Technology

By: History.com Editors

Updated: August 21, 2018 | Original: April 20, 2010

The Civil War was a time of great social and political upheaval. It was also a time of great technological change. Inventors and military men devised new types of weapons, such as the repeating rifle and the submarine, that forever changed the way that wars were fought. Even more important were the technologies that did not specifically have to do with the war, like the railroad and the telegraph. Innovations like these did not just change the way people fought wars–they also changed the way people lived.

New Kinds of Weapons

Before the Civil War , infantry soldiers typically carried muskets that held just one bullet at a time. The range of these muskets was about 250 yards. However, a soldier trying to aim and shoot with any accuracy would have to stand much closer to his target, since the weapon’s “effective range” was only about 80 yards. Therefore, armies typically fought battles at a relatively close range.

Did you know? The rifle-musket and the Minié bullet are thought to account for around 90 percent ofCivil Warcasualties.

Rifles, by contrast, had a much greater range than muskets did–a rifle could shoot a bullet up to 1,000 yards–and were more accurate. However, until the 1850s it was nearly impossible to use these guns in battle because, since a rifle’s bullet had roughly the same diameter as its barrel, they took too long to load. (Soldiers sometimes had to pound the bullet into the barrel with a mallet.)

In 1848, a French army officer named Claude Minié invented a cone-shaped lead bullet with a diameter smaller than that of the rifle barrel. Soldiers could load these “Minié balls” quickly, without the aid of ramrods or mallets. Rifles with Minié bullets were more accurate, and therefore deadlier, than muskets were, which forced infantries to change the way they fought: Even troops who were far from the line of fire had to protect themselves by building elaborate trenches and other fortifications.

“Repeaters”

Rifles with Minié bullets were easy and quick to load, but soldiers still had to pause and reload after each shot. This was inefficient and dangerous. By 1863, however, there was another option: so-called repeating rifles, or weapons that could fire more than one bullet before needing a reload. The most famous of these guns, the Spencer carbine, could fire seven shots in 30 seconds.

Like many other Civil War technologies, these weapons were available to Northern troops but not Southern ones: Southern factories had neither the equipment nor the know-how to produce them. “I think the Johnnys [Confederate soldiers] are getting rattled; they are afraid of our repeating rifles,” one Union soldier wrote. “They say we are not fair, that we have guns that we load up on Sunday and shoot all the rest of the week.”

Balloons and Submarines

Other newfangled weapons took to the air–for example, Union spies floated above Confederate encampments and battle lines in hydrogen-filled passenger balloons, sending reconnaissance information back to their commanders via telegraph–and to the sea. “Iron-clad” warships prowled up and down the coast, maintaining a Union blockade of Confederate ports.

For their part, Confederate sailors tried to sink these ironclads with submarines. The first of these, the Confederate C.S.S. Hunley, was a metal tube that was 40 feet long, 4 feet across, and held an 8-man crew. In 1864, the Hunley sank the Union blockade ship Housatonic off the coast of Charleston but was itself wrecked in the process.

The Railroad

More important than these advanced weapons were larger-scale technological innovations such as the railroad. Once again, the Union had the advantage. When the war began, there were 22,000 miles of railroad track in the North and just 9,000 in the South, and the North had almost all of the nation’s track and locomotive factories. Furthermore, Northern tracks tended to be “standard gauge,” which meant that any train car could ride on any track. Southern tracks, by contrast, were not standardized, so people and goods frequently had to switch cars as they traveled–an expensive and inefficient system.

Union officials used railroads to move troops and supplies from one place to another. They also used thousands of soldiers to keep tracks and trains safe from Confederate attack.

The Telegraph

Abraham Lincoln was the first president who was able to communicate on the spot with his officers on the battlefield. The White House telegraph office enabled him to monitor battlefield reports, lead real-time strategy meetings and deliver orders to his men. Here, as well, the Confederate army was at a disadvantage: They lacked the technological and industrial ability to conduct such a large-scale communication campaign.

In 1861, the Union Army established the U.S. Military Telegraph Corps, led by a young railroad man named Andrew Carnegie . The next year alone, the U.S.M.T.C. trained 1,200 operators, strung 4,000 miles of telegraph wire and sent more than a million messages to and from the battlefield.

Civil War Photography

The Civil War was the first war to be documented through the lens of a camera. However, the era’s photographic process was far too elaborate for candid pictures. Taking and developing photos using the so-called “wet-plate” process was a meticulous, multi-step procedure that required more than one “camera operator” and lots of chemicals and equipment. As a result, the images of the Civil War are not action snapshots: They are portraits and landscapes. It was not until the 20th century that photographers were able to take non-posed pictures on the battlefield.

Technological innovation had an enormous impact on the way people fought the Civil War and on the way they remember it. Many of these inventions have played important roles in military and civilian life ever since.

HISTORY Vault: The Secret History of the Civil War

The American Civil War is one of the most studied and dissected events in our history—but what you don't know may surprise you.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

The Invention of the Telegraph Changed Communication Forever

A communication revolution wired the world in the 19th century

- Famous Inventions

- Famous Inventors

- Patents & Trademarks

- Invention Timelines

- Computers & The Internet

- American History

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- Asian History

- European History

- Latin American History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- The 20th Century

- Women's History

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/McNamara-headshot-history1800s-5b7422c046e0fb00504dcf97.jpg)

When British officials wished to communicate between London and the naval base at Portsmouth in the early 1800s, they utilized a system called a semaphore chain. A series of towers built on high points of land held contraptions with shutters, and men working the shutters could flash signals from tower to tower.

A semaphore message could be relayed the 85 miles between Portsmouth and London in about 15 minutes. Clever as the system was, it was really just an improvement on signal fires, which had been used since ancient times.

There was a need for much faster communication. And by the middle of the century, Britain’s semaphore chain was obsolete.

The Invention of the Telegraph

An American professor, Samuel F.B. Morse , began experimenting with sending communications via electromagnetic signal in the early 1830s. In 1838 he was able to demonstrate the device by sending a message across two miles of wire in Morristown, New Jersey.

Morse eventually received funds from Congress to install a line for demonstration between Washington, D.C., and Baltimore. After an abortive effort to bury wires, it was decided to hang them from poles, and wire was strung between the two cities.

On May 24, 1844, Morse, stationed in the Supreme Court chambers, which were then in the US Capitol, sent a message to his assistant Alfred Vail in Baltimore. The famous first message: “What hath God wrought.”

News Traveled Quickly After the Invention of the Telegraph

The practical importance of the telegraph was obvious, and in 1846 a new business, the Associated Press, began using the rapidly spreading telegraph lines to send dispatches to newspaper offices. Election results were gathered via telegraph by the AP for the first time for the 1848 presidential election, won by Zachary Taylor .

In the following year AP workers stationed in Halifax, Nova Scotia, begin intercepting news arriving on boats from Europe and telegraphing it to New York, where it could appear in print days before the boats reached New York harbor.

Abraham Lincoln Was a Technological President

By the time Abraham Lincoln became president the telegraph had become an accepted part of American life. Lincoln's first State of the Union message was transmitted over the telegraph wires, as the New York Times reported on December 4, 1861:

The message of President Lincoln was telegraphed yesterday to all parts of the loyal states. The message contained 7, 578 words, and was all received in this city in one hour and 32 minutes, a feat of telegraphing unparalleled in the Old or New World.

Lincoln's own fascination with the technology led him to spend many hours during the Civil War in the telegraph room of the War Department building near the White House. The young men who manned the telegraph equipment later recalled him sometimes staying overnight, awaiting messages from his military commanders .

The president would generally write his messages in longhand, and telegraph operators would relay them, in military cipher, to the front. Some of Lincoln's messages are examples of emphatic brevity, such as when he advised General Ulysses S. Grant, at City Point, Virginia in August 1864: “Hold on with a bulldog grip, and chew and choke as much as possible. A. Lincoln.”

A Telegraph Cable Reached Under the Atlantic Ocean

During the Civil War construction of telegraph lines to the west proceeded, and news from the distant territories could be sent to the eastern cities almost instantly. But the biggest challenge, which seemed utterly impossible, would be to lay a telegraph cable under the ocean from North America to Europe.

In 1851 a functional telegraph cable had been laid across the English Channel. Not only could news travel between Paris and London, but the technological feat seemed to symbolize the peace between Britain and France just a few decades after the Napoleonic Wars. Soon telegraph companies began surveying the coast of Nova Scotia to prepare for laying cable.

An American businessman, Cyrus Field, became involved in the plan to put a cable across the Atlantic in 1854. Field raised money from his wealthy neighbors in New York City’s Gramercy Park neighborhood, and a new company was formed, the New York, Newfoundland, and London Telegraph Company.

In 1857, two ships chartered by Field's company began laying the 2,500 miles of cable, setting off from Ireland's Dingle Peninsula. The initial effort soon failed, and another attempt was put off until the following year.

Telegraph Messages Crossed the Ocean By Undersea Cable

The effort to lay the cable in 1858 met with problems, but they were overcome and on August 5, 1858, Cyrus Field was able to send a message from Newfoundland to Ireland via the cable. On August 16 Queen Victoria sent a congratulatory message to President James Buchanan.

Cyrus Field was treated as a hero upon arrival in New York City, but soon the cable went dead. Field resolved to perfect the cable, and by the end of the Civil War he was able to arrange more financing. An attempt to lay cable in 1865 failed when the cable snapped just 600 miles from Newfoundland.