Milestone Documents

Executive Order 9066: Resulting in Japanese-American Incarceration (1942)

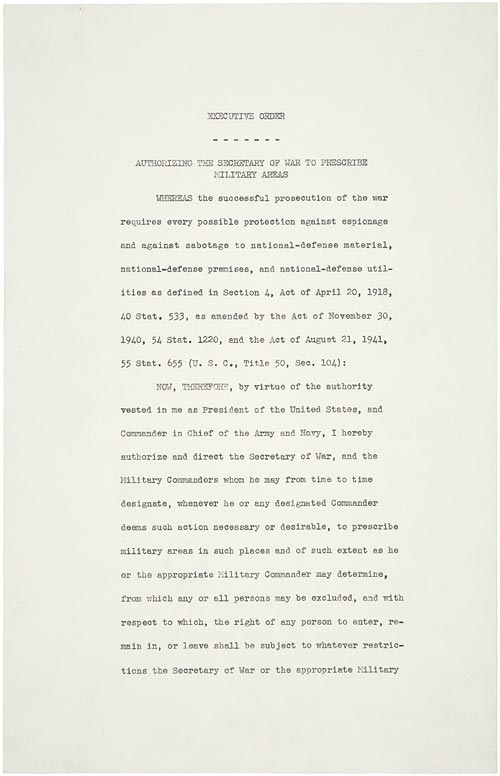

Citation: Executive Order 9066, February 19, 1942; General Records of the Unites States Government; Record Group 11; National Archives.

View All Pages in the National Archives Catalog

View Transcript

Issued by President Franklin Roosevelt on February 19, 1942, this order authorized the forced removal of all persons deemed a threat to national security from the West Coast to "relocation centers" further inland – resulting in the incarceration of Japanese Americans.

Between 1861 and 1940, approximately 275,000 Japanese immigrated to Hawaii and the mainland United States, the majority arriving between 1898 and 1924, when quotas were adopted that ended Asian immigration. Many worked in Hawaiian sugarcane fields as contract laborers. After their contracts expired, a small number remained and opened up shops. Other Japanese immigrants settled on the West Coast of mainland United States, cultivating marginal farmlands and fruit orchards, fishing, and operating small businesses. Their efforts yielded impressive results. Japanese Americans controlled less than 4 percent of California’s farmland in 1940, but they produced more than 10 percent of the total value of the state’s farm resources.

As was the case with other immigrant groups, Japanese Americans settled in ethnic neighborhoods and established schools, houses of worship, and economic and cultural institutions. Ethnic concentration was further increased by real estate agents who would not sell properties to Japanese Americans outside of existing Japanese American enclaves and by a 1913 act passed by the California Assembly restricting land ownership to those eligible to be citizens. In 1922, the U.S. Supreme Court, in Ozawa v. United States , upheld the government’s right to deny U.S. citizenship to Japanese immigrants.

On December 7, 1941, the Empire of Japan attacked the United States at the Pearl Harbor Naval Base in Hawaii. The attack launched a rash of fear about national security, especially on the West Coast. This combined with economic competition, distrust over cultural separateness, and long-standing anti-Asian racism turned into disaster for Japanese Americans.

Lobbyists from western states, many representing competing economic interests or nativist groups, pressured Congress and the President to remove persons of Japanese descent from the west coast, both foreign born ( issei – meaning “first generation” of Japanese in the U.S.) and American citizens ( nisei – the second generation of Japanese in America, U.S. citizens by birthright.) During congressional committee hearings, Department of Justice representatives raised constitutional and ethical objections to the proposal, so the U.S. Army carried out the task instead.

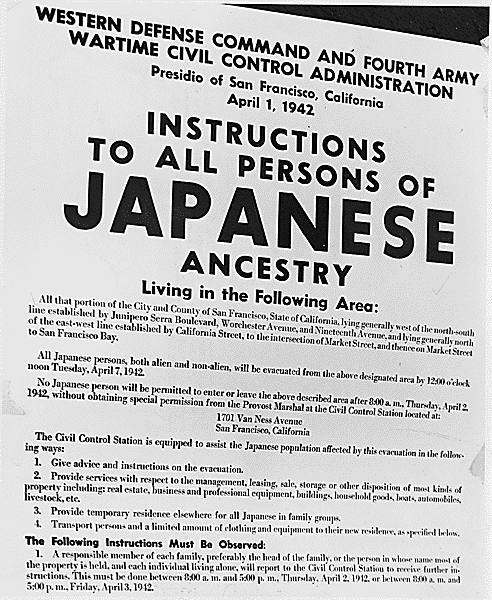

The West Coast was divided into military zones, and on February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 that authorized military commanders to exclude civilians from military areas. Although the language of the order did not specify any ethnic group, Lieutenant General John L. DeWitt of the Western Defense Command proceeded to announce curfews that included only Japanese Americans.

General DeWitt first encouraged voluntary evacuation by Japanese Americans from a limited number of areas. About seven percent of the total Japanese American population in these areas complied. Then on March 29, 1942, under the authority of Roosevelt's executive order, DeWitt issued Public Proclamation No. 4, which began the forced evacuation and detention of Japanese-American West Coast residents on a 48-hour notice. Only a few days prior to the proclamation, on March 21, Congress had passed Public Law 503, which made violation of Executive Order 9066 a misdemeanor punishable by up to one year in prison and a $5,000 fine.

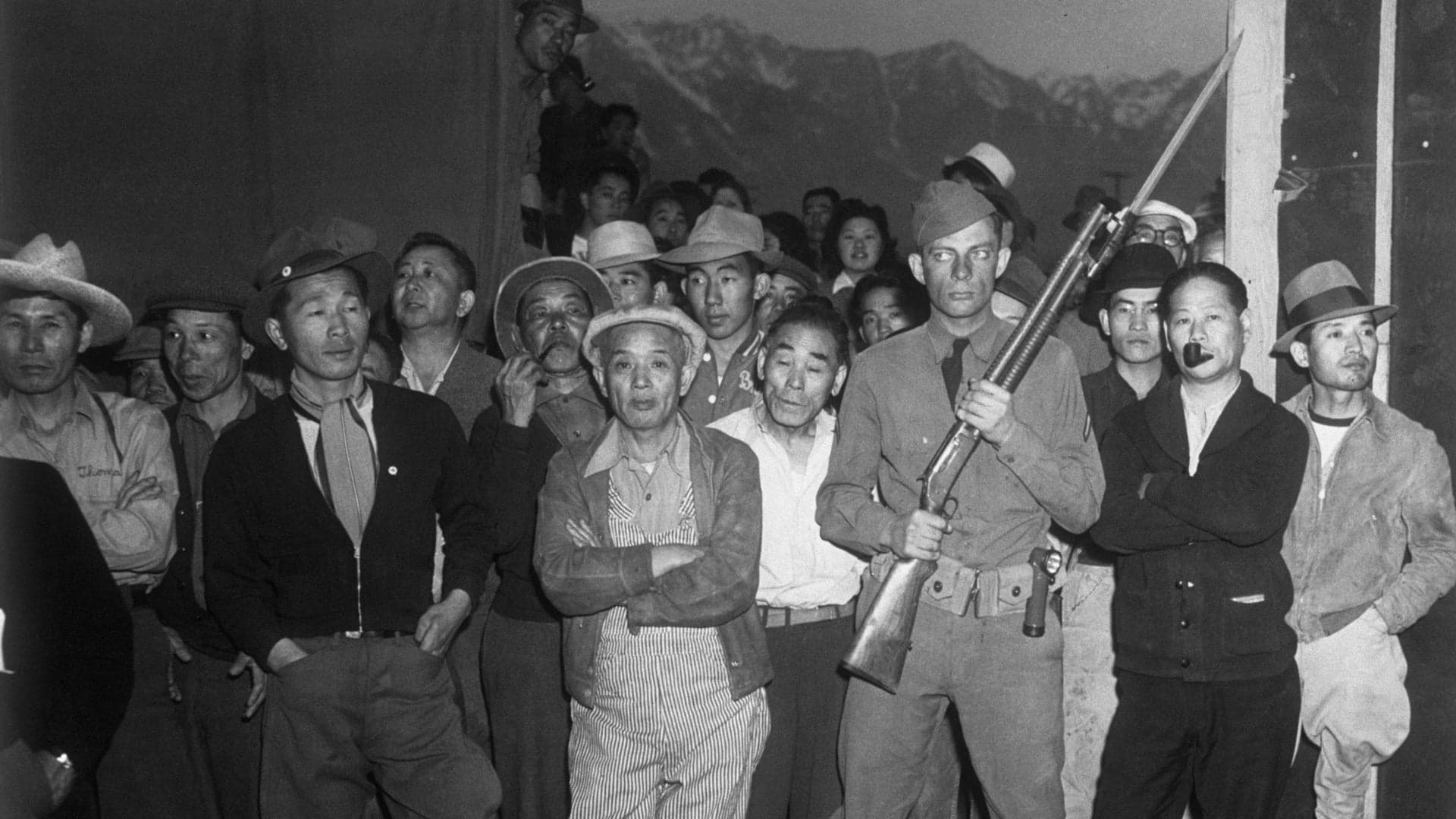

In the next six months, approximately 122,000 men, women, and children were forcibly moved to "assembly centers." They were then evacuated to and confined in isolated, fenced, and guarded "relocation centers," also known as "internment camps." The 10 sites were in remote areas in six western states and Arkansas: Heart Mountain in Wyoming, Tule Lake and Manzanar in California, Topaz in Utah, Poston and Gila River in Arizona, Granada in Colorado, Minidoka in Idaho, and Jerome and Rowher in Arkansas.

Nearly 70,000 of the evacuees were American citizens. The government made no charges against them, nor could they appeal their incarceration. All lost personal liberties; most lost homes and property as well. Although several Japanese Americans challenged the government’s actions in court cases, the Supreme Court upheld their legality. Nisei were nevertheless encouraged to serve in the armed forces, and some were also drafted. Altogether, more than 30,000 Japanese Americans served with distinction during World War II in segregated units.

For many years after the war, various individuals and groups sought compensation for those incarcerated. The speed of the "evacuation" forced many homeowners and businessmen to sell out quickly; total property loss is estimated at $1.3 billion, and net income loss at $2.7 billion (calculated in 1983 dollars based on a congressional commission investigation). The Japanese American Evacuation Claims Act of 1948, with amendments in 1951 and 1965, provided token payments for some property losses. More serious efforts to make amends took place in the early 1980s, when the congressionally established Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians held investigations and made recommendations. As a result, several bills were introduced in Congress from 1984 until 1988. In 1988, Public Law 100-383 acknowledged the injustice of the incarceration, apologized for it, and provided partial restitution – a $20,000 cash payment to each person who was incarcerated.

Teach with this document.

Previous Document Next Document

Executive Order No. 9066

The President

Executive Order

Authorizing the Secretary of War to Prescribe Military Areas

Whereas the successful prosecution of the war requires every possible protection against espionage and against sabotage to national-defense material, national-defense premises, and national-defense utilities as defined in Section 4, Act of April 20, 1918, 40 Stat. 533, as amended by the Act of November 30, 1940, 54 Stat. 1220, and the Act of August 21, 1941, 55 Stat. 655 (U.S.C., Title 50, Sec. 104);

Now, therefore, by virtue of the authority vested in me as President of the United States, and Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy, I hereby authorize and direct the Secretary of War, and the Military Commanders whom he may from time to time designate, whenever he or any designated Commander deems such action necessary or desirable, to prescribe military areas in such places and of such extent as he or the appropriate Military Commander may determine, from which any or all persons may be excluded, and with respect to which, the right of any person to enter, remain in, or leave shall be subject to whatever restrictions the Secretary of War or the appropriate Military Commander may impose in his discretion. The Secretary of War is hereby authorized to provide for residents of any such area who are excluded therefrom, such transportation, food, shelter, and other accommodations as may be necessary, in the judgment of the Secretary of War or the said Military Commander, and until other arrangements are made, to accomplish the purpose of this order. The designation of military areas in any region or locality shall supersede designations of prohibited and restricted areas by the Attorney General under the Proclamations of December 7 and 8, 1941, and shall supersede the responsibility and authority of the Attorney General under the said Proclamations in respect of such prohibited and restricted areas.

I hereby further authorize and direct the Secretary of War and the said Military Commanders to take such other steps as he or the appropriate Military Commander may deem advisable to enforce compliance with the restrictions applicable to each Military area hereinabove authorized to be designated, including the use of Federal troops and other Federal Agencies, with authority to accept assistance of state and local agencies.

I hereby further authorize and direct all Executive Departments, independent establishments and other Federal Agencies, to assist the Secretary of War or the said Military Commanders in carrying out this Executive Order, including the furnishing of medical aid, hospitalization, food, clothing, transportation, use of land, shelter, and other supplies, equipment, utilities, facilities, and services.

This order shall not be construed as modifying or limiting in any way the authority heretofore granted under Executive Order No. 8972, dated December 12, 1941, nor shall it be construed as limiting or modifying the duty and responsibility of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, with respect to the investigation of alleged acts of sabotage or the duty and responsibility of the Attorney General and the Department of Justice under the Proclamations of December 7 and 8, 1941, prescribing regulations for the conduct and control of alien enemies, except as such duty and responsibility is superseded by the designation of military areas hereunder.

Franklin D. Roosevelt

The White House,

February 19, 1942.

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

The Legacy of Order 9066 and Japanese American Internment

On Feb. 19, 1942, Pres. Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 , granting Secretary of War Henry Lewis Stimson and his commanders the power “to prescribe military areas in such places and of such extent as he or the appropriate Military Commander may determine, from which any or all persons may be excluded.” While the order named no specific group or location, nearly all Japanese American citizens on the West Coast were soon forced to uproot themselves and their families for relocation to internment camps. For three years, Japanese Americans were forced to live in sparse conditions, surrounded by barbed wire under a continuous cloud of suspicion and threat. Seventy-five years later, the forced internment of Japanese Americans during World War II has widely been denounced as racist and xenophobic and a period of national shame.

The order was issued two months after the Japanese military attack on Pearl Harbor , but its targeting of Japanese Americans and the resulting incarceration also had roots in a long history of racist and anti-Asian immigrant federal policies that stretched back to restrictive immigration policies of the late 1800s . Despite lack of any evidence supporting suspicions that Japanese Americans posed a significant threat as saboteurs and concerns about the infringement of civil liberties , political weight was thrown behind the idea of rounding up Japanese Americans on the West Coast and moving them to detention centers in the interior of the country in the name of national security ( John J. McCloy , assistant secretary of war, famously said that if the choice was between national security and civil liberties enshrined in the U.S. Constitution , the Constitution “was just a scrap of paper”).

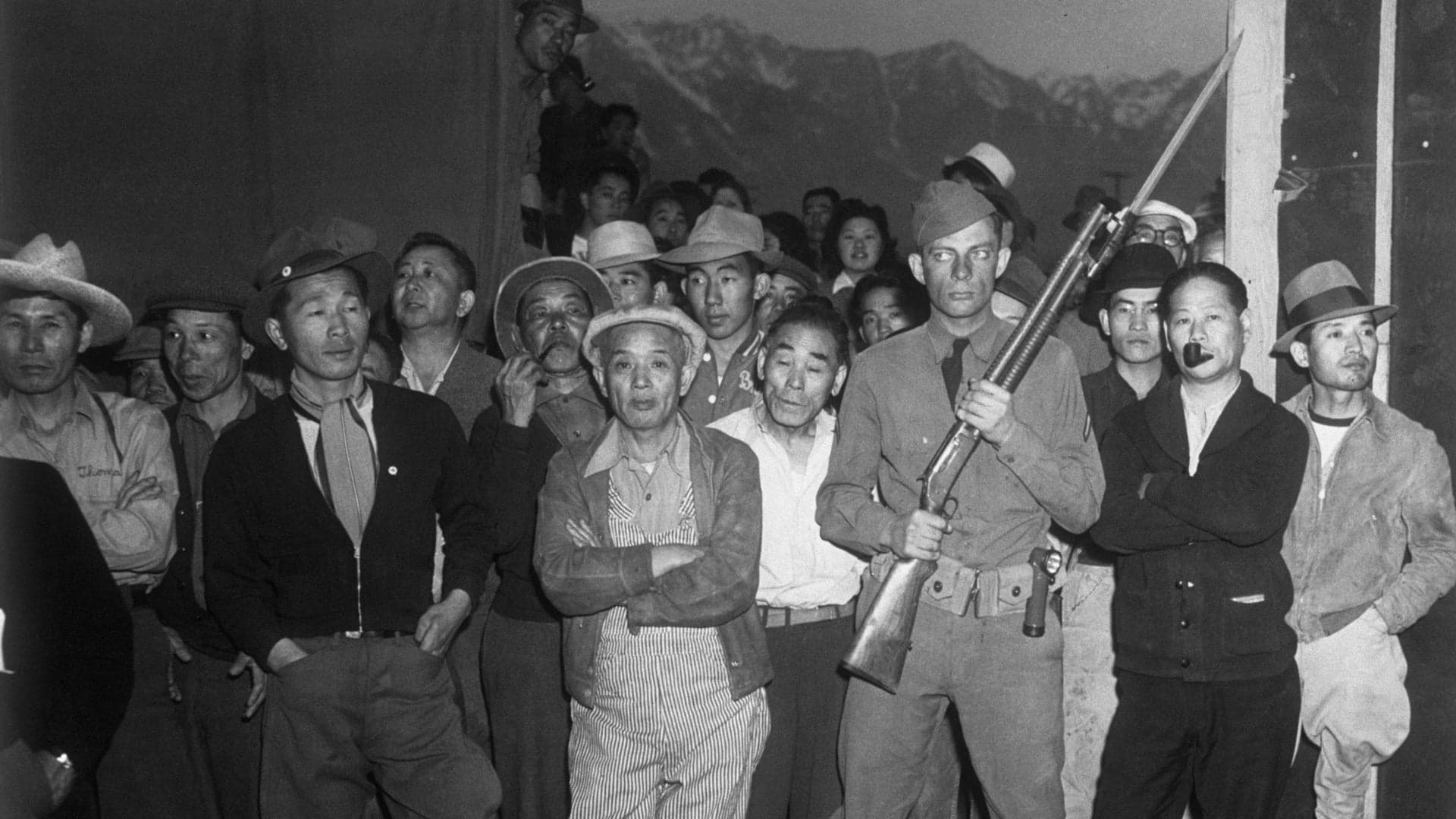

After a brief period of being subjected to nighttime curfews, on March 31, 1942, Japanese Americans who lived on the West Coast were ordered to register themselves and their family members and were forced to leave whatever they couldn’t carry behind; many had no choice but to sell their property and businesses for a fraction of their worth, often to their own neighbors and former friends. From 1942 to 1945, roughly 120,000 U.S. citizens of Japanese heritage were incarcerated at 1 of 10 camps located in California, Arizona, Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, and Arkansas. Living conditions were bare bones, with uninsulated barracks heated by coal-burning stoves, common latrines, little hot running water, and food being rationed. Although Japanese Americans attempted to create a semblance of community by setting up schools, sports, and other activities, they did so under the constant watch of armed guards with orders to shoot anyone who tried to leave.

The incarceration sparked various protests and legal fights, notably Korematsu v. United States , which ruled 6–3 to uphold the conviction of Fred Korematsu for refusing to submit to the order. However, in 2011, the U.S. solicitor general confirmed that the predecessor who had argued for the government in this case had lied to the court by withholding a U.S. Naval Intelligence report concluding that Japanese Americans didn’t pose a threat to the U.S. at the time. While the last camp was finally closed in 1946, it wasn’t until 1976 that Pres. Gerald Ford officially rescinded Executive Order 9066, stating: “We now know what we should have known then—not only was that evacuation wrong, but Japanese Americans were and are loyal Americans….I call upon the American people to affirm with me this American Promise—that we have learned from the tragedy of that long-ago experience forever to treasure liberty and justice for each individual American, and resolve that this kind of action shall never again be repeated.”

In 1988, Congress formally apologized to Japanese Americans, and the Civil Liberties Act awarded $20,000 each to some 80,000 surviving internees and their families. While presidential commissions have attributed the order to racial prejudice , war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership, even 75 years later the legacy of Executive Order 9066 still reverberates as some scholars and politicians continue to attempt justifying the incarceration of Japanese American citizens, using this shameful period of American history as a blueprint for further xenophobic policies targeting other immigrants and American citizens.

Learn More About This Topic

- Learn more about Executive Order 9066

- What is the term for second-generation U.S.-born children of Japanese immigrants?

- Actor George Takei has spoken of his childhood spent at this internment camp

- Which U.S. department opposed moving innocent civilians to internment camps?

Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066

Japanese internment during world war ii.

by Rhae Lynn Barnes

During World War II, the United States incarcerated nearly all of its Japanese American residents. Japanese Americans were concentrated on the West Coast in makeshift internment camps. Edward J. Ennis, the director of the United States Justice Department’s Alien Enemy Control Unit in 1943 explained that, “within twenty-four hours after the attack on Pearl Harbor 1,000 Japanese aliens had been apprehended, and within a week a total of 3,000 alien enemies of German, Italian, and Japanese nationality were in the custody of the Immigration and Naturalization Service.”

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed an Executive Order, Number 9066, giving the federal government the power to relocate 120,000 Japanese Americans to internment camps because they lived in residential zones now considered high-risk targets. The program was rapidly put in place on the West Coast. Nearly two-thirds of the Japanese Americans forced to leave their homes had been born in the United States, making them U.S. Citizens through birth, not aliens. Their first-generation immigrant parents, however, due to stringent provisions put in place by the 1790 Naturalization Act , did not have the opportunity to become naturalized citizens. This law, written during the Early Republic, limited naturalization to free white men (and later to those of African descent born in the United States during Reconstruction). This law was upheld from 1790 to 1922 by the Supreme Court in Ozawa v. United States . Takao Ozawa attempted to become a U.S. Citizen, but the Supreme Court stipulated “whiteness” had to do with being Caucasian, not lightness of skin. The only route to citizenship for an Asian in America was to be born after 1898, when the Supreme Court Case, Wong Kim Ark v. United States deemed citizenship by birth on U.S. soil acceptable. In short: even if Japanese immigrants had wanted to become citizens, it was illegal, which made them resident aliens by default. Their inability to obtain citizenship allowed for abuse by racially motivated segregation, such as California’s 1913 law, the Alien Land Act, which prohibited aliens who could not obtain citizenship from the right to “acquire, possess, enjoy, transmit, and inherit real property.” What does this mean? In California, if a Japanese family worked a farm and the parents died, their children could not inherit the property or sell it. Property could not be “possessed” in the first place, and therefore could not be “transmitted” or sold, making them a legally alien landless labor force.

Immediately after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Lieutenant General John Lesesne DeWitt became the commanding general of the Western Defense Command. He spoke very candidly about the perceived threat of Japanese Americans in a report to the War Department in February 1942, before Roosevelt enacted his Executive Order.

DeWitt argued: “In the war in which we are now engaged racial affinities are not severed by migration. The Japanese race is an enemy race and while many second and third generation Japanese born on United States soil, possessed of United States Citizenship, have become ‘Americanized,’ the racial strains are undiluted. To conclude otherwise is to expect that children born of white parents on Japanese soil sever all racial affinity and become loyal Japanese subjects, ready to ?ght and, if necessary, to die for Japan in a war against the nation of their parents. That Japan is allied with Germany and Italy in this struggle is no ground for assuming that any Japanese, barred from assimilation by convention as he is, though born and raised in theUnited States, will not turn against this nation when the ?nal test of loyalty comes. It, therefore, follows that along the vital Paci?c Coast over 112,000 potential enemies, of Japanese extraction, are at large today. There are indications that these are organized and ready for concerted action at a favorable opportunity. The very fact that no sabotage has taken place to date is a disturbing and con?rming indication that such action will be taken.”

Although no immigrants or citizens of German or Italian ancestry underwent mass removal and internment, the United States government deemed Japanese Americans a security threat. The United States claimed their geographic vicinity, cultural ties, and ancestral links to the Japanese Empire would enable them to be spies.

Japanese Americans were forced to vacate their homes, sell their businesses, and their possessions in less than two weeks (the majority only having a few days). Before they officially relocated to camps like Manzanar in California, they lived in assembly centers such as racetracks and fairgrounds, living in animal pens. Then, once they arrived at the relocation camps, the “prisoners” had to construct places in which to live. None of the Americans placed in the ten major internment camps were officially accused or charged with espionage or underwent a trial. Public outcry was minimal. It is important to keep in mind that this occurred during the height of Jim Crow segregation and before the 1954 Supreme Court Case Brown v. Board would overturn the “separate but equal” dogma in place since 1896.

Below is a film highlighting both survivors and historians that gives a wonderful overview of the relocation and internment process, the legal battle to overturn the Executive Order, and ultimately the U.S government’s reparations program in the 1980s.

If you are looking for a multimedia classroom exercise, below is a U.S.propaganda film that could be used as a discussion piece in relation to oral histories from survivors or other written primary sources.

Below is the oral history testimony of Sue Kunitomi Embrey , who the United States forcibly relocated to the California Japanese internment camp Manzanar. Her story comes in eleven parts.

In 1941, the United States sent Japanese American civil rights activist Yuri Kochiyama to the Jerome War Relocation Center in Jerome, Arkansas. Her father was imprisoned the day of the Pearl Harbor attack, while two of her brothers enlisted in the United States army.

Below, actress StacyAnn Chin performs an excerpt from Yuri Kochiyama’s memoir.

For More Information: Visit the U.S. History Scene Reading list for World War II. Visit the History Matter’s page on Korematsu v. United States , detailing the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that upheld internment. While there, you can also check out their page featuring an interview conducted with an elderly Nisei . Ansel Adams’ photographs of Japanese-American Internment at Manzanar can be viewed on the Library of Congress “American Memory” page. The LOC’s Prints and Photographs Divisio n also houses a number of prints addressing internment. Read L. E. Salyer, “Baptism by Fire: Race, Military Service, and US Citizenship Policy, 1918-1935,” Journal of American History 91: 847-876. Also very useful is Yoosun Park, Facilitating Injustice: Tracing the Role of Social Workers in the World War II Internment of Japanese Americans . Social Service Review, Vol. 82, No. 3 (September 2008), pp. 447-483.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

PODCAST: HISTORY UNPLUGGED J. Edgar Hoover’s 50-Year Career of Blackmail, Entrapment, and Taking Down Communist Spies

The Encyclopedia: One Book’s Quest to Hold the Sum of All Knowledge PODCAST: HISTORY UNPLUGGED

Executive Order 9066: What Was It and What Did It Do?

Cite This Article

- How Much Can One Individual Alter History? More and Less...

- Why Did Hitler Hate Jews? We Have Some Answers

- Reasons Against Dropping the Atomic Bomb

- Is Russia Communist Today? Find Out Here!

- Phonetic Alphabet: How Soldiers Communicated

- How Many Americans Died in WW2? Here Is A Breakdown

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

This Day In History : February 19

Changing the day will navigate the page to that given day in history. You can navigate days by using left and right arrows

FDR orders Japanese Americans into internment camps

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signs Executive Order 9066, initiating a controversial World War II policy with lasting consequences for Japanese Americans. The document ordered the forced removal of resident "enemy aliens" from parts of the West vaguely identified as military areas.

After the bombing of Pearl Harbor by the Japanese in 1941, Roosevelt came under increasing pressure by military and political advisors to address the nation’s fears of further Japanese attack or sabotage, particularly on the West Coast, where naval ports, commercial shipping and agriculture were most vulnerable. Included in the off-limits military areas referred to in the order were ill-defined areas around West Coast cities, ports and industrial and agricultural regions. While 9066 also affected Italian and German Americans, the largest numbers of detainees were by far Japanese Americans.

On the West Coast, long-standing racism against Japanese Americans, motivated in part by jealousy over their commercial success, erupted after Pearl Harbor into furious demands to remove them en masse to Relocation Centers for the duration of the war.

Japanese immigrants and their descendants, regardless of American citizenship status or length of residence, were systematically rounded up and placed in prison camps. Evacuees, as they were sometimes called, could take only as many possessions as they could carry and were forcibly placed in crude, cramped quarters. In the western states, camps on remote and barren sites such as Manzanar and Tule Lake housed thousands of families whose lives were interrupted and in some cases destroyed by Executive Order 9066. Many lost businesses, farms and loved ones as a result.

Roosevelt delegated enforcement of 9066 to the War Department, telling Secretary of War Henry Stimson to be as reasonable as possible in executing the order. Attorney General Francis Biddle recalled Roosevelt’s grim determination to do whatever he thought was necessary to win the war. Biddle observed that Roosevelt was not much concerned with the gravity or implications of issuing an order that essentially contradicted the Bill of Rights .

In her memoirs, Eleanor Roosevelt recalled being completely floored by her husband’s action. A fierce proponent of civil rights, Eleanor hoped to change Roosevelt’s mind, but when she brought the subject up with him, he interrupted her and told her never to mention it again.

During the war, the U.S. Supreme Court heard two cases challenging the constitutionality of Executive Order 9066, upholding it both times. Finally, on February 19, 1976, decades after the war, Gerald Ford signed an order prohibiting the executive branch from re-instituting the notorious and tragic World War II order. In 1988, President Ronald Reagan issued a public apology on behalf of the government and authorized reparations for former Japanese American internees or their descendants.

Japanese Internment Camps

Executive Order 9066 On February 19, 1942, shortly after the bombing of Pearl Harbor by Japanese forces, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 with the stated intention of preventing espionage on American shores. Military zones were created in California, Washington and Oregon—states with a large population of Japanese Americans. Then Roosevelt’s executive order forcibly removed […]

U.S. Propaganda Film Shows ‘Normal’ Life in WWII Japanese Internment Camps

The U.S. government, for its part, tried to assure the rest of the country that its policy was justified, and that those Japanese Americans forced to live in the prison camps were happy.

Eleanor Roosevelt’s Work to Oppose Japanese Internment

The first lady did what she could to support Japanese Americans during WWII—without appearing to defy FDR's Executive Order 9066.

Also on This Day in History February | 19

John Singleton, 24, becomes first Black director nominated for an Oscar

"the feminine mystique" by betty friedan is published.

This Day in History Video: What Happened on February 19

Tiger woods apologizes for extramarital affairs, polish astronomer copernicus is born, aaron burr arrested for alleged treason.

Wake Up to This Day in History

Sign up now to learn about This Day in History straight from your inbox. Get all of today's events in just one email featuring a range of topics.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Donner Party rescued from the Sierra Nevada Mountains

U.s. marines invade iwo jima, chicago seven acquitted of conspiracy charges, thomas edison patents the phonograph, united states calls situation in el salvador "a communist plot", congress overlooks benedict arnold for promotion.

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Course: US history > Unit 7

- Beginning of World War II

- 1940 - Axis gains momentum in World War II

- 1941 Axis momentum accelerates in WW2

- Pearl Harbor

- FDR and World War II

Japanese internment

- American women and World War II

- 1942 Tide turning in World War II in Europe

- World War II in the Pacific in 1942

- 1943 Axis losing in Europe

- American progress in the Pacific in 1944

- 1944 - Allies advance further in Europe

- 1945 - End of World War II

- The Manhattan Project and the atomic bomb

- The United Nations

- The Second World War

- Shaping American national identity from 1890 to 1945

- President Franklin Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066 resulted in the relocation of 112,000 Japanese Americans living on the West Coast into internment camps during the Second World War.

- Japanese Americans sold their businesses and houses for a fraction of their value before being sent to the camps. In the process, they lost their livelihoods and much of their lifesavings.

- In Korematsu v. United States (1944) the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of internment. In 1988, the United States issued an official apology for internment and compensated survivors.

Executive Order 9066

Korematsu v. united states (1944), aftermath and redress, what do you think.

- On internment, see Ira Katznelson, Fear Itself: The New Deal and The Origins of Our Time (New York: Liveright Publishing, 2013), 339; Roger Daniels, Sandra C. Taylor, Harry H.L. Kitano, eds., Japanese Americans, from Relocation to Redress (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1991); Wendy L. Ng, Japanese American Internment during World War II: A History and Reference Guide (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 2002).

- See David M. Kennedy, Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929-1945 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 754.

- Kennedy, Freedom from Fear , 756.

- Kennedy, Freedom from Fear , 757.

- “Abyss of racism . . .” quoted in Peter Irons, Justice at War: The Story of the Japanese-American Internment Cases (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993), 335. “I dissent . . .” quoted in Otis Stephens and John Scheb, American Constitutional Law , v. 1 (Belmont, CA: Thomson/Wadsworth, 2008), 224.

- Kennedy, Freedom from Fear , 759.

- Kennedy, Freedom from Fear , 760.

- William Yoshino and John Tateishi, " The Japanese American Incarceration: The Journey to Redress ," excerpted from Human Rights , American Bar Association, Spring 2000.

Want to join the conversation?

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

By continuing to browse the site you are agreeing to our use of cookies and similar tracking technologies described in our privacy policy .

Karen Inouye

Reliving Injustice 75 Years Later: Executive Order 9066 Then and Now

/ Article Archive

/ Reliving Injustice 75 Years Later: Executive Order 9066 Then and Now

Publication Date

February 17, 2017

Current Events in Historical Context

In February 1942, following the bombing of Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 , which directed state and local authorities to locate and detain Japanese American citizens and their family members in the western United States at a number of prison sites. In addition to being given only days to prepare for their imprisonment, Japanese Americans received little information about their destinations, the proposed length of their stay, or the conditions they would endure. They were told to pack what they could carry and then were abruptly forced from their homes. Of the roughly 120,000 people who were subjected to this treatment (primarily in California, Oregon, Arizona, and Washington), most spent the next three years in prison.

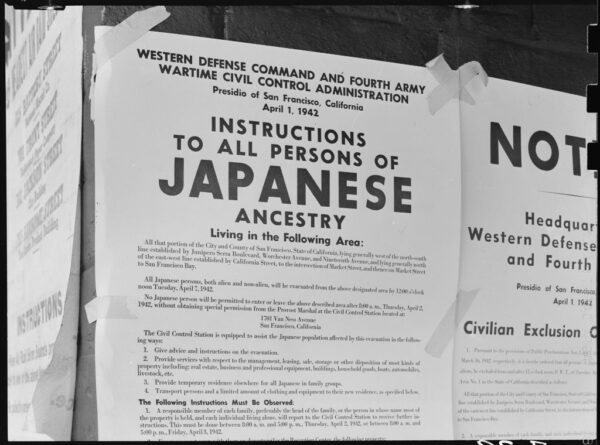

An Exclusion Order commanding the removal of Japanese Americans from a section of San Francisco. Wikimedia Commons

Before being formally incarcerated, Japanese Americans were first detained in one of 17 so-called “assembly centers.” The bulk of these were located in California, with three other sites in Oregon, Arizona, and Washington. The majority of these temporary jails were makeshift arrangements, such as former fairgrounds and horse tracks. Following this interim period, inmates eventually arrived at prisons where they would stay long term. Called relocation centers in most official correspondence (but also internment camps and, on occasion, concentration camps), these prisons were created and administered by the War Relocation Authority. A total of 10 such prisons existed: Gila River and Poston in Arizona; Granada in Colorado; Heart Mountain in Wyoming; Jerome and Rohwer in Arkansas; Manzanar and Tule Lake in California; Topaz in Utah; and Minidoka in Idaho.

On January 30, we celebrated the legacy of civil rights hero Fred Korematsu , who was one of three Japanese Americans to challenge the constitutionality of Executive Order 9066 before the Supreme Court. February 19 will mark the 75th anniversary of Roosevelt signing the order. Even as we acknowledge these historical milestones, we face the horrific realization that the same dangerous impulses and rhetoric that led to the mass imprisonment of over 100,000 innocent citizens and their family members once again lie at the heart of President Donald J. Trump’s recent executive orders regarding immigration. In this critical moment, history has especially important lessons to teach us about racism, religious prejudice, and the importance of basic human rights.

Much attention has rightly been paid to the legal and economic harm that institutionalized bigotry can cause, as well as to the various factors that feed that bigotry. Even as we bear these important matters in mind as teachers and as members of civil society, we might consider lifting our eyes for a moment from this sadly familiar historical terrain, direct them toward the horizon, and consider the most elusive, but also perhaps most important, challenge before us. In response to discourses of fear and withdrawal from the world, we must strive for a more measured, historically informed, and above all empathic engagement with the world.

Take, for instance, the fallout of wartime incarceration specifically in the United States. (Canada, too, undertook to remove all people of Japanese ancestry from the West Coast.) At high schools and universities from California to Washington, Japanese American students were summarily expelled, despite having never even been arrested or charged with any crime. Families lost their homes, their businesses; entire communities were uprooted and dispersed inland. Life in prison only added insult to these various preliminary injuries. In both the short-term way stations and longer-term prisons, inmates endured repeated violations of their civil and human rights, as well as a host of related indignities—all the while being surveyed for possible inclusion in the American war effort. (In February 1943, inmates were subjected to what became known as the Loyalty Questionnaire , an ancestor of “extreme vetting” that comprised approximately 30 questions designed to assess the suitability of Japanese Americans for placement outside prisons and, in case of eligible males, military service.) Life under these conditions left inmates in a constant state of distress and uncertainty about their safety and future, particularly given the clear link between wartime incarceration and the years of anti-Asian prejudice that preceded it. Indeed, there is evidence, both contemporary and observed at the time , that that distress and uncertainty never fully subsided, and that many families continue to suffer the aftereffects of unjust incarceration based on racial and religious prejudice.

As we witness the government of this country lurch from reactionary move to reactionary move, we would do well to reflect on not only large-scale events and topics, but also other sorts of cultural work, such as that which the Japanese American community has tended to pursue in the wake of wartime injustice. From congressional testimony in support of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 , which granted reparations to Japanese Americans who had been imprisoned, to participating in retroactive diploma ceremonies all along the West Coast, these people have sought to demonstrate much more than the fact that the past is repeatable, and that such repetitions are avoidable. They also have sought to demonstrate to others that action derives first and foremost from direct, emotional investment in human rights and civil liberties. This is what Fred Korematsu had in mind when he spoke and wrote against religious and racial profiling after 9/11: “I know what it is like to be at the other end of such scapegoating and how difficult it is to clear one’s name after unjustified suspicions are endorsed as fact by the government.”

Injustice, whether proposed casually or pursued programmatically, exacts a toll that is personal as much as anything else, and its corrosive effects work at an individual level. But they affect not only the target of unjust behavior and vicious sentiment; they also affect those who trade in such behavior and voice such sentiment. The people who peddle stereotypes seek to perpetuate convenient abstractions drained of all emotion, save fear, which drives us away from one another and into increasing isolation. Empathy, by contrast, draws us together. It is the force that can bind us to one another personally and, in so doing, help us to move beyond dry templates for thought and toward genuinely productive action. Informed by a rigorous understanding of the past, it may be our most powerful tool for navigating the challenges of both the present and the future.

’s new book, The Long Afterlife of Nikkei Wartime Incarceration (Stanford Univ. Press, 2016), maps the intergenerational, cross-cultural, and cross-racial consequences of suspending rights in the name of national security.

This post first appeared on AHA Today .

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History , date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.

Join the AHA

The AHA brings together historians from all specializations and all work contexts, embracing the breadth and variety of activity in history today.

- Career Services

- USC Law Library

- About USC Gould

- Mission Statement

- Message from the Dean

- History of USC Gould

- Board of Councilors

- Jurist-in-Residence Program

- Social Media

- Consumer Information (ABA Required Disclosures)

- Contact USC Gould School of Law

- Academic Calendar

- LLM Programs

- Legal Master’s Programs

- Certificates

- Undergraduate Programs

- Bar Admissions

- Concentrations

- Corporate & Custom Education

- Course Descriptions

- Experiential Learning and Externships

- Progressive Degree Programs

Faculty & Research

- Faculty and Lecturer Directory

- Research and Scholarship

- Faculty in the News

- Distinctions and Awards

- Centers and Initiatives

- Workshops and Conferences

- Alumni Association

- Alumni Events

- USC Gould Alumni Class Notes

- USC Law Magazine

- Contact USC Gould Alumni Relations

- Student Life Office

- Student Life and Organizations

- Commencement

- Academic Services and Honors Programs

- Student Wellbeing

- Diversity, Equity, Inclusion and Belonging

- Law School Resources

- USC Resources

- Business Law & Economics

- Constitutional Law

- New Building Initiative

- Law Leadership Society

- How to Give to USC Gould

- Gift Planning

- BS Legal Studies

Explore by Interest

- Legal Master’s Programs

Quick Links

- Graduate & International Programs

- Giving to Gould

- How to Give

75 Years Later: The Impact of Executive Order 9066

Five USC Gould students reflect upon the time their families spent interned in camps during WWII

On Feb. 19, 1942 President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed “Executive Order 9066,” which paved the way for the forced removal and incarceration of 120,000 Japanese-Americans from the West Coast during World War II.

Families were forced to leave their homes and businesses and move inland to camps, sometimes thousands of miles from home. Many families were not allowed to return to their homes for years. The same Order led to one of the most infamous cases in the history of the United States Supreme Court, Korematsu v. United States , 323 U.S. 214 (1944).

| Cynthia Chiu '19's high school-age grandmother, photographed at the internment camp in Jerome, Arkansas |

| Mike Mikawa '17 and his grandparents |

| Tule Lake Segregation Center Prison, photo by Mike Mikawa '17 |

| Camp Jerome, 1944, as depicted in Cynthia Chiu's grandmother's yearbook |

| Mike Mikawa '17 visiting Poston site. |

| Cynthia Chiu's grandfather, who was sent to Italy with the 442nd Regiment. |

| A photo from Mike Mikawa's 2008 visit to the Manzanar Memorial. |

Explore Related

- Immigration Law

Related Stories

The Power of Social Activism

Lights, cameras, legal matters.

USC Gould School of Law 699 Exposition Boulevard Los Angeles, California 90089-0071 213-740-7331

USC Gould School of Law

699 Exposition Boulevard

Los Angeles, California 90089-0071

- Academic Programs

- Acceptances

- Articles and Book Chapters

- Awards and Honors

- Book Chapters

- Book Reviews

- Business Law and Economics

- Center for Dispute Resolution

- Center for Law and Philosophy

- Center for Law and Social Science

- Center for Law History and Culture

- Center for Transnational Law and Business

- Centers and Institutes

- Continuing Legal Education

- Contribution to Amicus Briefs

- Contributions to Books

- Criminal Justice

- Degree Programs

- Dispute Resolution

- Election Law

- Experiential Learning

- Externships

- Graduate & International Programs

- Hidden Articles

- Housing Law and Policy Clinic

- Immigration Clinic

- Initiative and Referendum Institute

- Institute for Corporate Counsel

- Institute on Entertainment Law and Business

- Intellectual Property and Technology Law Clinic

- Intellectual Property Institute

- International Human Rights Clinic

- International Law

- Jurist in Residence

- Legal History

- Legal Theory and Jurisprudence

- LLM On Campus

- Media Advisories

- Media, Entertainment and Technology Law

- Mediation Clinic

- MSL On Campus

- Other Publications

- Other Works

- Planned Giving

- Post-Conviction Justice Project

- Practitioner Guides

- Presentations / Lectures / Workshops

- Public Interest Law

- Publications

- Publications and Shorter Works

- Publications in Books

- Publications in Law Reviews

- Publications in Peer-reviewed Journals

- Real Estate Law and Business Forum

- Redefined Blog

- Research & Scholarship

- Saks Institute for Mental Health Law, Policy, and Ethics

- Scholarly Publications

- Short Pieces

- Small Business Clinic

- Tax Institute

- Trust and Estate Conference

- Uncategorized

- Undergraduate Law

- Working Papers

- Works in Progress

Copyright © 2024 USC Gould. All Rights Reserved.

- For the Media

- Make a Gift

- Emergency Information

- Privacy Policy

- Notice of Non-Discrimination

- Digital Accessibility

- Contact Webmaster

OUT OF THE DESERT

Executive Order 9066

Entering world war ii: pearl harbor and executive order 9066, on december 7, 1941, japan launched a surprise attack on pearl harbor and the united states entered world war ii. less than three months later, president franklin d. roosevelt signed executive order 9066 declaring parts of california, arizona, washington state, and oregon a war zone operating under military rule. despite the absence of documented cases of espionage, approximately 100,000 persons of japanese heritage were forcibly removed from the west coast to inland internment camps during the spring and summer of 1942. of that number, two-thirds were u.s.-born citizens., during the first two years of world war ii, the united states sought to maintain neutrality even while aiding allies with war materials and supplemental military units. to further deter japanese military expansion in the pacific, the united states imposed economic sanctions on japan—one of several factors that instigated japan’s attack on pearl harbor., on february 19, 1942, president roosevelt signed executive order 9066. the order outlined the mass exclusion and incarceration of all persons of japanese ancestry as justified by “military necessity.” the exclusion order led to the internment of issei (first-generation immigrants ineligible for u.s. citizenship), nisei (second-generation american citizens by birth), and kibei (american-born u.s. citizens raised or educated in japan) alike. indicating the racialized nature of internment, german and italian americans were not subject to mass incarceration., following their “evacuation” from the west coast, internees were initially placed in temporary “assembly centers” before their eventual assignment to one of ten “war relocation centers” in the interior operated by the new civilian agency, the war relocation authority (wra). in hawai‘i, internment was not implemented because the incarceration of close to 40% of the population would have crippled local infrastructure. however, community leaders were detained in one of five camps in the territory or sent to mainland wra camps..

Top of page

Primary Source Set Japanese American Internment

- Student Discovery Set - free ebook on iBooks External

The resources in this primary source set are intended for classroom use. If your use will be beyond a single classroom, please review the copyright and fair use guidelines.

Teacher’s Guide

To help your students analyze these primary sources, get a graphic organizer and guides: Analysis Tool and Guides

Between 1942 and 1945, thousands of Japanese Americans were, regardless of U.S. citizenship, required to evacuate their homes and businesses and move to remote war relocation and internment camps run by the U.S. Government. This proved to be an extremely trying experience for many of those who lived in the camps, and to this day remains a controversial topic.

Historical Background

“Yesterday, December 7, 1941 - a date which will live in infamy - the United States of America was suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces of the Empire of Japan,” declared President Franklin D. Roosevelt in his address to a joint session of Congress.

The repercussions of this event in the U.S. were immediate. In cities and towns up and down the West Coast, prominent Japanese Americans were arrested, while friends and neighbors of Japanese Americans viewed them with distrust. Within a short time, Japanese Americans were forced out of their jobs and many experienced public abuse, even attacks.

When the president issued Executive Order 9066 in February 1942, he authorized the evacuation and relocation of “any and all persons” from “military areas.” Within months, all of California and much of Washington and Oregon had been declared military areas. The process of relocating thousands of Japanese Americans began.

The relocation process was confusing, frustrating, and frightening. Japanese Americans were required to register and received identification numbers. They had to be inoculated against communicable diseases. They were given just days to divest themselves of all that they owned, including businesses and family homes. Bringing only what they could carry, they were told to report to assembly centers: large facilities like racetracks and fairgrounds. These centers became temporary housing for thousands of men, women and children. Stables and livestock stalls often served as living and sleeping quarters.

There was no privacy for individuals – all their daily needs were accommodated in public facilities. Internees waited, for weeks that sometimes became months, to be moved from the assembly centers to their assigned war relocation centers.

Life in the Camps

These hardships continued when internees reached their internment camp. Located in remote, desolate, inhospitable areas, the camps were prison-like, with barbed wire borders and guards in watchtowers. Many people, not always family members, shared small living spaces and, again, public areas served internees’ personal needs. Eventually, life in the camps settled into routines. Adults did what they could to make living quarters more accommodating. Schools were established for the educational needs of the young. Residents performed the jobs necessary to run the camps. Self-governing bodies emerged, as did opportunities for gainful employment and for adult teaching and learning of new skills. Evidence of normal community living appeared as newspapers, churches, gardening, musical groups, sports teams, and enclaves of writers and artists emerged. The barbed wire and watchtowers, however remained in place.

Serving Their Country

Despite this treatment, Japanese Americans did their best to get through the internment experience and serve their country during a time of war. More than 30,000 Japanese American men enlisted in the armed forces. The all Japanese American 442nd Regiment became the most decorated unit of its size in U.S. history.

After the War

First generation Japanese immigrants were hardest hit by the internment. Many lost everything - homes, businesses, farms, respect, status and sense of achievement. Their children and grandchildren also experienced disruptions to their lives, but they emerged after the war with lives that, while changed, were not destroyed. These second- and third-generation Japanese American citizens began to shoulder responsibility for leadership in the Japanese American community.

Suggestions for Teachers

Select and analyze one image of life in a relocation center. What can be learned from the image? What questions does the image raise? Analyze additional images from the set to see what questions can be answered, and what new questions come up. Students might organize their thinking into categories such as living conditions, recreation, or work. If time permits, select one or two questions for further research using primary or secondary sources.

Ask students to study a selection of items related to life in a relocation center and form a hypothesis about how the people shown reacted to being interned, and then list details from one or more primary sources to support the hypothesis. Alternatively, give students a hypothesis, a selection of items from the set, and ask some students to find evidence to support the hypothesis, and others to find evidence that refutes it. Compare photographs by two or more photographers. Consider purpose, style, intended audience, and the impact of each image.

Watch the oral history clip from Norman Ikari. Ask students to write a brief retelling of the oral history in their own words, and then allow time for students to compare their writing with a partner’s. What aspect of the oral history did each student emphasize? What is the significance of this oral history? Ask students to think about how this oral history supports, contradicts, or adds to their understanding of the period or events. How does encountering this history firsthand change its emotional impact? (For more questions and ideas, consult the Teacher’s Guide: Analyzing Oral History.)

This primary source set also provides an opportunity to help students understand that different times shape different cultural values and mores. The set may also provide impetus for discussions that compare and contrast the unfair treatment of other segments of the U.S. population, in America’s past and today.

Additional Resources

Ansel Adams’s Photographs of Japanese-American Internment at Manzanar

Japanese Immigrants: Behind the Wire

American Memory Timeline: Great Depression and World War II - Japanese American Internment

- Advisory Board

- Guest Authors

- NEW: Podcast

- Artificial Intelligence (AI)

- Climate Change

- Congressional Oversight

- Counterterrorism

- Cybersecurity

- Disinformation

- Human Rights

- Immigration

- Intelligence activities

- International Criminal Law

- Israel-Hamas War

- January 6th Attack on US Capitol

- Law of Armed Conflict

- Local Voices

- Racial Justice

- Social Media Platforms

- United Nations

- Use of Force

- Russia-Ukraine War

- Trump Trials

Featured Articles

- Write for Just Security

- Signups for A.M. and P.M. emails

80 Years Later, Preventing Another Executive Order 9066 Requires Recognizing Its Lessons

by David Inoue

February 18, 2022

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

Filed under:

Accountability , Discrimination , Executive Order 9066 , Racial Justice

Editors’ note: This is part of our series on the 80th anniversary of Executive Order 9066, signed on Feb. 19, 1942.

On Feb. 19, 80 years ago, President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 (EO 9066), an act that would directly lead to the mass incarceration of nearly 120,000 people for no other reason than their Japanese ancestry. In the years since, the government has apologized for the injustice inflicted upon the Japanese American community during the war. But we must not mistake what happened for an isolated single injustice, but recognize it as part of a pattern of racism and xenophobia that has permeated the United States’ history and continues today.

The Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) was founded in 1929 in response to the racism experienced by the Japanese immigrants ( issei ) and their citizen-by-birth children ( nisei ). Today, as Executive Director of JACL, I work alongside my colleagues and civil rights groups from other communities to safeguard the civil and human rights of all communities who are affected by injustice and bigotry.

In a cycle that illustrates the recurring patterns of racism in U.S. immigration history, racially targeted immigration policies, beginning with the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 , initially opened up opportunities for Japanese laborers to immigrate. But the anti-Asian policies soon spread to successive communities, including the Japanese, with the Gentlemen’s Agreement of 1907 significantly curtailing immigration from Japan. Throughout the U.S. west, Alien Land Laws barred non-citizens from owning property, and in 1913, California passed the first Alien Land Law specifically targeting Japanese immigrants. In 1924, immigration laws were changed to expressly exclude Japanese immigration, ending the Gentlemen’s Agreement.

JACL was founded in response to these policies and also as a means of activism for the nisei, who were more firmly American than Japanese in their education and culture and sought to distinguish themselves as citizens of their chosen country. Unfortunately, their numbers were not significant enough to effect change to the discriminatory policies, only significant enough to continue to engender the hatred and racism that would blossom in the lead up to and after the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

EO 9066 was issued under the auspices of “military necessity.” Notable about EO 9066 is that “Japanese” is not actually mentioned . The order grants the military the wide latitude to exclude or incarcerate any individuals deemed a military threat because of where they were located. Once this was implemented, the intent was clear that U.S. officials exercising authority under the Order were targeting specifically and nearly exclusively people of Japanese ancestry.

And yet, all the evidence the government had, indicated very little threat from the broad ethnic Japanese population. Some threats had been identified, but it was suspected that the Japanese government actually had more white spies employed than Japanese within America’s borders.

In 1980, Congress appointed the nine-member Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC) to officially study the incarceration that took place under EO 9066. It is through the work of the CWRIC and other research that we now know the “military necessity” was entirely a facade that had no truth to it whatsoever.

What is, and was even at the time, well known is the deep-seated racist attitudes of General John DeWitt, who led the calls for mass incarceration. But ultimately, while DeWitt may have provided much of the basis, incarceration would not have happened without the consent and action of the entire governmental apparatus. Perhaps the most quoted line from Personal Justice Denied , the Report of the CWRIC, is: “The broad historical causes which shaped these decisions were race prejudice, war hysteria and a failure of political leadership.” Incarceration was made possible by racism that existed both in society and in the halls of power.

Ultimately, the result of the CWRIC was a set of five recommendations for redress:

- That Congress pass a joint resolution offering a public apology;

- That the President pardon those convicted of curfew violations and review other wartime convictions based on discrimination due to race or ethnicity;

- That Congress direct agencies to review applications for restitution of positions, status or entitlements lost by individuals because of their Japanese ethnicity during the war;

- That Congress appropriate funds to establish an educational foundation to address the nation’s need for redress; and

- That Congress provide redress of $20,000 to each of the remaining 60,000 surviving persons of Japanese ancestry incarcerated during the war.

JACL had prioritized three items, the individual redress payments, the apology, and the establishment of a fund for education. This last is what has endured in the form of the Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant program and in JACL’s and other community organizations’ primary purpose of educating the public on the legacy of our community’s incarceration. That education highlights the lasting importance of understanding what led to EO 9066, including in the context of current times and parallels to discrimination and bigotry faced by other communities.

In the wake of 9/11, the Japanese American community saw the potential for Roosevelt’s proclamation of “a day that would live in infamy” – and the domestic repression that followed – repeat itself, as the country rallied to respond to the first attacks on American territory since Pearl Harbor. JACL leadership at the time consisted of executive director John Tateishi, who had led much of JACL’s efforts in the redress campaign, and president Floyd Mori, who was well connected in Washington, D.C., and the civil rights community. JACL was swift in its response with a statement and outreach to the Muslim community. The presence of Transportation Secretary Norman Mineta, who had been incarcerated at Heart Mountain as a child, in George W. Bush’s cabinet informed the president of the legacy of Japanese American incarceration, and President Bush promised that what happened to Japanese Americans would not happen to Muslim Americans.

Unfortunately, while formal mass incarceration like that under EO 9066 did not manifest itself, we have seen the infiltration of racism in policy implementation. Despite all the proclamations that there is no racially based screening at the TSA lines, early on it was well known that those stopped for additional screening were often identifiable as Muslim, or even Sikh, because of the identifiable marker of wearing a turban. And a 2017 ACLU report found that the TSA’s own documents showed that its supposedly race-neutral “behavior detection program” resulted in racial harassment and profiling.

And, as Professor Lori Bannai writes in another Just Security piece published today , in a move that echoes EO 9066, the Trump administration’s travel ban used the pretext of a claimed security threat to exclude people from countries that were almost all majority Muslim.

As the COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in extraordinary measures to prevent the disease from spreading, this has also led to the invocation of a public health emergency impacting U.S. immigration policies. Title 42 of the Public Health Service Act was enacted nearly 80 years ago to give the government the tools to combat pandemic, just as we are today. Among other things, it grants the government the power to exclude or detain people who have recently been in a country where a communicable disease is present, for the purposes of excluding the disease from the United States. But during the COVID-19 pandemic – when the disease is already crossing borders in myriad ways – Title 42 has been applied by both the Trump and Biden administrations to severely restrict entry by non-citizens, including asylum-seekers with claims protected under international law , at the United States’ southern border. The implementation has meant that thousands of people seeking asylum in the United States have been kept out, and even many already in the country have been detained and deported. These actions have largely targeted Black and Brown immigrant communities, even as U.S. borders have remained open for commerce and other forms of travel.

In our work at JACL, we continue to unfortunately see the failure to learn the lessons of EO 9066: that laws and policies can be weaponized against minority communities. But we also see hope in another lesson from the Japanese American experience: that the U.S. government has the capacity to provide redress for past wrongs. Japanese Americans have joined the fight for Black reparations for the past injustices of slavery and Jim Crow, and ongoing police violence against communities of color, recognizing these as state actions for which the government must similarly take responsibility. A proposal for a commission similar to CWRIC to study Black reparations has been proposed since 1989, the year after redress passed. It has been introduced in Congress every year since and now has the support of over 215 members of Congress , but still has not seen a vote.

The late justice Antonin Scalia once stated the two worst decisions by the Supreme Court were Korematsu and Dredd Scott, which essentially upheld the injustices of Japanese American incarceration and slavery, respectively. The United States has apologized and compensated for one of those mistakes, but has yet to tangibly act to apologize or compensate for the other.

As we remember EO 9066, it is important to remember it in the context of what happened before and since. For those of us in the United States, it is one example of an unfortunate pattern of racism in our country, and important to our understanding that our government maintains policies that – sometimes in text, but, today, more often in practice and implementation – discriminate against minority communities. As we look back, we can also hope that Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., was correct that the moral arc of the universe continues to bend towards justice. But it is our responsibility to work to bend it. To ensure that we never again repeat the atrocity of what happened to Japanese Americans, we must work cooperatively to root out all forms of racism that continue to exist and must continue grappling with the many ways that it has shaped our history.

IMAGE: President Ronald Reagan signs the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 in an official ceremony. Left to right: Hawaii Sen. Spark Matsunaga, California Rep. Norman Mineta, Hawaii Rep. Pat Saiki, California Sen. Pete Wilson, Alaska Rep. Don Young, California Rep. Bob Matsui, California Rep. Bill Lowery, and JACL President Harry Kajihara . Courtesy of the Ronald Reagan Presidential library via Wikicommons.

About the author(s), david inoue.

David Inoue, MPH/MHA, has served as Executive Director for the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) since July 2017. He previously worked in health care policy and administration.

Send A Letter To The Editor

Read these related stories next:

Trump trials clearinghouse.

by Norman L. Eisen , Ryan Goodman , Siven Watt and Francois Barrilleaux

Aug 15th, 2024

Breaking the Deadlock: New Talks Needed to Help End Sudan’s Violence and Offer a Glimmer of Hope

by Quscondy Abdulshafi

Aug 13th, 2024

The Year(s) of Magical Thinking on Sudan

by Payton Knopf

Aug 12th, 2024

Making Russia Pay to Strengthen Ukraine

by Svitlana Starosvit

Jul 30th, 2024

US Arrests Former Syrian Prison Chief – But Will the Charges Prove Equal to His Crimes?

by Rebecca Hamilton and Paras Shah

Jul 25th, 2024

Judge Cannon Finds Special Counsel Unconstitutional in Trump Classified Documents Case: What’s Next for Jack Smith?

by Adam Klasfeld

Jul 15th, 2024

Death Toll Climbs in Ukraine With Russia’s `Double-Tap’ Strikes

by Mercedes Sapuppo and Shelby Magid

Jul 8th, 2024

Engaging Africa in the ICC Prosecutor’s New Policy Paper on Complementarity and Cooperation

by Geoffrey Lugano

Not Just Trump: America’s Growing Problem With Race

by Ambassador P. Michael McKinley (ret.)

Jul 3rd, 2024

The Just Security Podcast: ICC Arrest Warrants for Russian Attacks on Ukraine’s Power Grid

by Kateryna Busol , Rebecca Hamilton , Paras Shah , Audrey Balliette and Harrison Blank

Jun 28th, 2024

Trump’s Mar-a-Lago Search Challenge Flounders: Judge Signals Warrant Passed Muster

Jun 25th, 2024

A Modern Rush for ‘Green Deal’ Minerals Challenges Troubled Governance in the Western Balkans

by Valery Perry

Upcoming events

|

|

- What is Reacting?

- About the Consortium

- Contact and Team

- News and Announcements

- Reacting Editorial Board

- Member Directory

- Brilliancy Prize for Reacting

- Dana Johnson Gorlin Fellowship

- Reacting Instructors Winning Awards

- Fellow Travelers

- 2024 Annual Institute

- Past Events

- News and Blog

- Acid Rain in Europe

- American Revolution

- Art in Paris

- Athens 403 BCE

- Augsburg, 1530

- Bacon's Rebellion

- Charles Darwin

- Charles Darwin Second Edition

- Chicago 1968

- Climate Change in Copenhagen

- Collapse of Apartheid

- Confucianism

- Constitutional Convention

- Council of Nicaea

- Council of Nicaea Second Edition

- Crisis of Catiline

- Eleventh Pillar

- Europe on the Brink

- Forest Diplomacy

- French Revolution

- Fourth Crusade

- Greenwich Village 2nd Edition

- Greenwich Village 1913

- Indian Independence 1945

- Kentucky 1861

- Mexico in Revolution

- Paterson, 1913

- Red Clay 1835

- Rwanda 1994

- Stages of Power

- Trial of Anne Hutchinson

- Trial of Galileo

- Vietnam Veterans Memorial

- Watergate 1973

- Weimar Germany

- Yalta, 1945

- Argentina, 1985

- Birth of the Public Sphere

- Christine de Pizan

- Congressional AIDS Hearings

- Diet and Killer Diseases

- Election of 1912

- Ending the Troubles

- Engines of Mischief, 1817-1818

- Enlightenment Game

- Firestone in Liberia

- Food or Famine

- Game of Sages

- Grandsons of Genghis

- Guerrilla Girls

- Harlem 1919

- Ides of March

- Investiture Controversy

- Japanese Exclusion 1906-1915

- Josianic Reform

- Kansas, 1999

- 1894 Korea: Kabo Reforms

- London 1854: Cholera

- Memory Reconsidered

- Physician-Assisted Suicide

- 1349: The Plague

- Radical Reconstruction

- Russian Literary Journals

- The Second Crusade

- Versailles 1919

- Are Atoms Real?

- Challenging Authority

- Cigarette Century

- Conclave 1492

- The Condition of England

- Fate of Mary Stuart

- Jumonville Incident

- North Korean Hunger Games

- Athens Besieged

- Ban the Jesuits

- British Modernism Microgame

- Executive Order 9066

- Making History: The Breakup Microgame

- Pluto Debate

- Roman Prisoner's Dilemma

- Athens Reconciliation

- Chicago, 1968 Demo

- Food Fight Demo Game

- French Revolution Demo

- Wanli Dilemma Demo

- Games by Era

- Games by Geography

- Games for Small Classes

- Games for Large Classes

- French Language Games

- American History

- Economics & Labor

- Journalism Games

- Political Games

- Religious Games

- Race, Gender, and Sexuality

- Materials for Instructors

- Books, Essays, and Articles

- Apply to be a Mentee

- Apply to be a Mentor

- FAQ for GMs

- Game Author Resources

- Permissions Request Form

- Reacting in High Schools

| ', placeHolder = gadgetHorMenu.parents('.WaLayoutPlaceHolder'), placeHolderId = placeHolder && placeHolder.attr('data-componentId'), mobileState = false, isTouchSupported = !!(('ontouchstart' in window) || (window.DocumentTouch && document instanceof DocumentTouch) || (navigator.msPointerEnabled && navigator.msMaxTouchPoints)); function resizeMenu() { var i, len, fitMenuWidth = 0, menuItemPhantomWidth = 80; firstLevelMenu.html(holderInitialMenu).removeClass('adapted').css({ width: 'auto' }); // restore initial menu if (firstLevelMenu.width() > gadgetHorMenuContainer.width()) { // if menu oversize menuItemPhantomWidth = firstLevelMenu.addClass('adapted').append(phantomElement).children('.phantom').width(); for (i = 0, len = holderInitialMenu.size(); i |

EXECUTIVE ORDER 9066

Executive Order 9066: Japanese Americans after Pearl Harbor

by Michael A. Barnhart

|

|

| Conflict & War, Cultural & Social History, Political Science & Government, US History, Japanese American History

20th Century | Civil Rights, Political Concerns vs. Values, Japanese American History, Race

| Franklin D. Roosevelt, President ; Henry Stimson, ; Francis Biddle,

|

|

, , or .

This game is recommended for classes with 5-27+ students, but the ideal range is 9-16. If the number of players will exceed 16, then roles will be doubled as specified in a role assignment matrix in the Instructor's Manual. Tripling roles is possible. ⇧ |

| can access all downloadable materials (including expanded and updated materials) below. You will be asked to sign in before downloading. | | |

⇧ Back to top ⇧

Members can contact game authors directly . We invite instructors join our Facebook Faculty Lounge , where you'll find a wonderful community eager to help and answer questions. We also encourage you to submit your question for the forthcoming FAQ , and to check out our upcoming events .

| |

| | | |

⇧ Back to top of this page ⇧

- Teacher Opportunities

- AP U.S. Government Key Terms

- Bureaucracy & Regulation

- Campaigns & Elections

- Civil Rights & Civil Liberties

- Comparative Government

- Constitutional Foundation

- Criminal Law & Justice

- Economics & Financial Literacy

- English & Literature

- Environmental Policy & Land Use

- Executive Branch

- Federalism and State Issues

- Foreign Policy

- Gun Rights & Firearm Legislation

- Immigration

- Interest Groups & Lobbying

- Judicial Branch

- Legislative Branch

- Political Parties

- Science & Technology

- Social Services

- State History

- Supreme Court Cases

- U.S. History

- World History

Log-in to bookmark & organize content - it's free!

- Bell Ringers

- Lesson Plans

- Featured Resources

Bell Ringer: Japanese Internment Cases

Japanese internment cases.

Georgetown University law professor Cliff Sloan, author of "The Court at War," talked about three cases dealing with Japanese internment during World War II: Hirabayashi v. United States (1943), Korematsu v. United States (1944), and Ex parte Endo (1944).

Description

Bell ringer assignment.

- Based on the clip, what was Executive Order 9066?

- What was “upheld” in both Hirabayashi v. United States (1943) and Korematsu v. United States (1944)? Compare the two rulings.

- Who was Mitsuye Endo and what was her “claim?”

- How did the Supreme Court rule in Ex parte Endo (1944)? Why is Endo a “hero?”

Related Articles

- Hirabayashi v. United States (Oyez)

- Facts and Case Summary — Korematsu v. U.S. (United States Courts)

- Ex parte Endo, 323 U.S. 283 (1944) (Justia US Supreme Court Center)

Additional Resources

- Video Clip: President Bill Clinton Speaks About Civil Leader Fred T. Korematsu

- Bell Ringer: Japanese Internment Camp History and Artifacts

- Bell Ringer: Landmark Cases Series: Korematsu v United States - Executive Order 9066

- Bell Ringer: World War II: Executive Order 9066 and Japanese Americans

- Bell Ringer: Japanese American Soldiers in World War II

- Bell Ringer: Life in Japanese Internment Camps

- Bell Ringer: Internment During World War II

- Lesson Plan: Civil Liberties and Japanese Internment During World War II

- On This Day: Executive Order 9066 and Japanese-American Internment

Participants

- Discriminatory

- Ex Parte Endo (1944)

- Executive Order 9066

- Franklin D. Roosevelt

- Hirabayashi V. United States (1943)

- Incarcerate

- Korematsu V. United States (1944)

- Legislation

- World War Two (1939-45)

- Skip to global NPS navigation

- Skip to the main content

- Skip to the footer section

Exiting nps.gov

Executive order 9066.

EXECUTIVE ORDER ------- AUTHROIZING THE SECRETARY OF WAR TO PRESCRIBE MILITARY AREAS