Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- Write for Us

- BMJ Journals

You are here

- Volume 24, Issue 2

- Five tips for developing useful literature summary tables for writing review articles

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0157-5319 Ahtisham Younas 1 , 2 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0002-7839-8130 Parveen Ali 3 , 4

- 1 Memorial University of Newfoundland , St John's , Newfoundland , Canada

- 2 Swat College of Nursing , Pakistan

- 3 School of Nursing and Midwifery , University of Sheffield , Sheffield , South Yorkshire , UK

- 4 Sheffield University Interpersonal Violence Research Group , Sheffield University , Sheffield , UK

- Correspondence to Ahtisham Younas, Memorial University of Newfoundland, St John's, NL A1C 5C4, Canada; ay6133{at}mun.ca

https://doi.org/10.1136/ebnurs-2021-103417

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

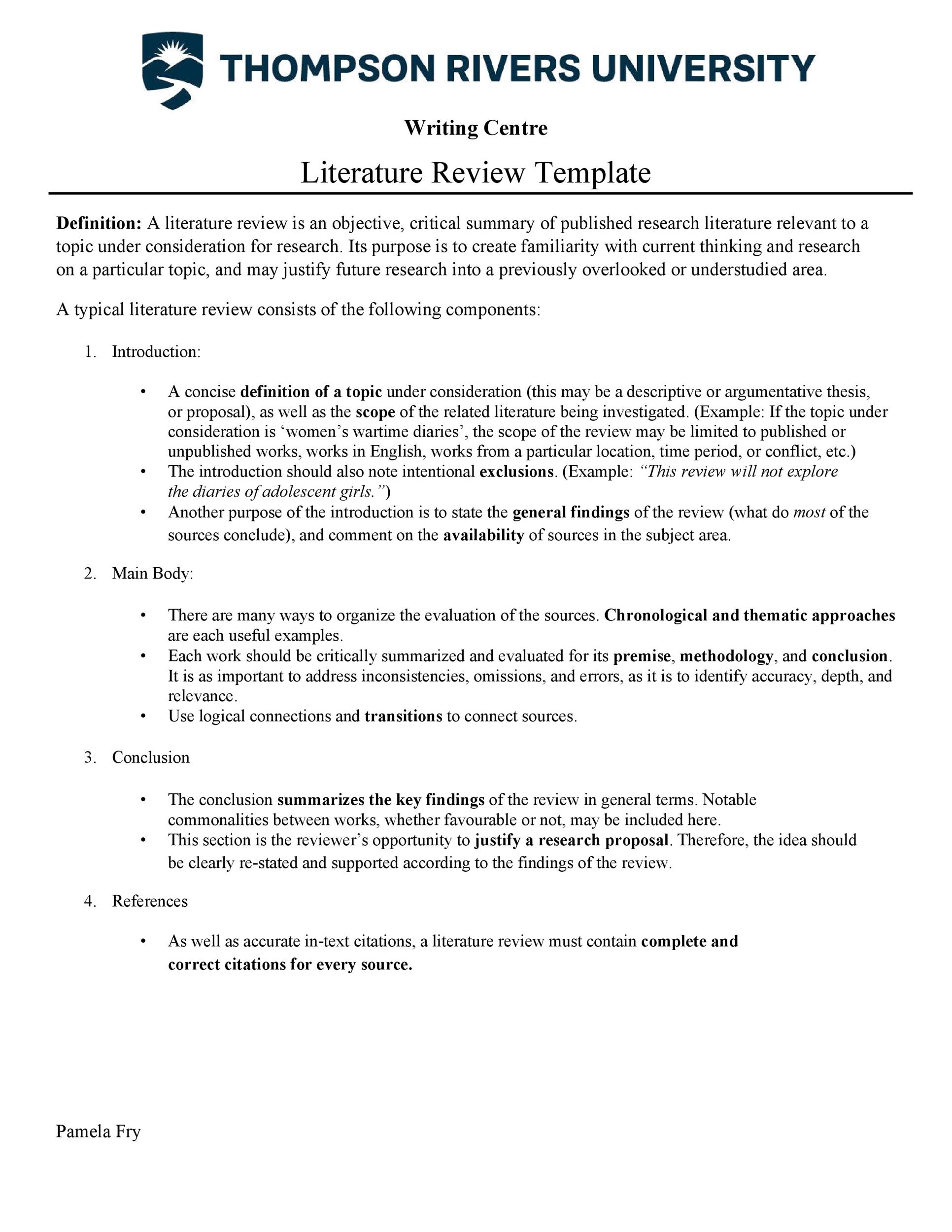

Introduction

Literature reviews offer a critical synthesis of empirical and theoretical literature to assess the strength of evidence, develop guidelines for practice and policymaking, and identify areas for future research. 1 It is often essential and usually the first task in any research endeavour, particularly in masters or doctoral level education. For effective data extraction and rigorous synthesis in reviews, the use of literature summary tables is of utmost importance. A literature summary table provides a synopsis of an included article. It succinctly presents its purpose, methods, findings and other relevant information pertinent to the review. The aim of developing these literature summary tables is to provide the reader with the information at one glance. Since there are multiple types of reviews (eg, systematic, integrative, scoping, critical and mixed methods) with distinct purposes and techniques, 2 there could be various approaches for developing literature summary tables making it a complex task specialty for the novice researchers or reviewers. Here, we offer five tips for authors of the review articles, relevant to all types of reviews, for creating useful and relevant literature summary tables. We also provide examples from our published reviews to illustrate how useful literature summary tables can be developed and what sort of information should be provided.

Tip 1: provide detailed information about frameworks and methods

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

Tabular literature summaries from a scoping review. Source: Rasheed et al . 3

The provision of information about conceptual and theoretical frameworks and methods is useful for several reasons. First, in quantitative (reviews synthesising the results of quantitative studies) and mixed reviews (reviews synthesising the results of both qualitative and quantitative studies to address a mixed review question), it allows the readers to assess the congruence of the core findings and methods with the adapted framework and tested assumptions. In qualitative reviews (reviews synthesising results of qualitative studies), this information is beneficial for readers to recognise the underlying philosophical and paradigmatic stance of the authors of the included articles. For example, imagine the authors of an article, included in a review, used phenomenological inquiry for their research. In that case, the review authors and the readers of the review need to know what kind of (transcendental or hermeneutic) philosophical stance guided the inquiry. Review authors should, therefore, include the philosophical stance in their literature summary for the particular article. Second, information about frameworks and methods enables review authors and readers to judge the quality of the research, which allows for discerning the strengths and limitations of the article. For example, if authors of an included article intended to develop a new scale and test its psychometric properties. To achieve this aim, they used a convenience sample of 150 participants and performed exploratory (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) on the same sample. Such an approach would indicate a flawed methodology because EFA and CFA should not be conducted on the same sample. The review authors must include this information in their summary table. Omitting this information from a summary could lead to the inclusion of a flawed article in the review, thereby jeopardising the review’s rigour.

Tip 2: include strengths and limitations for each article

Critical appraisal of individual articles included in a review is crucial for increasing the rigour of the review. Despite using various templates for critical appraisal, authors often do not provide detailed information about each reviewed article’s strengths and limitations. Merely noting the quality score based on standardised critical appraisal templates is not adequate because the readers should be able to identify the reasons for assigning a weak or moderate rating. Many recent critical appraisal checklists (eg, Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool) discourage review authors from assigning a quality score and recommend noting the main strengths and limitations of included studies. It is also vital that methodological and conceptual limitations and strengths of the articles included in the review are provided because not all review articles include empirical research papers. Rather some review synthesises the theoretical aspects of articles. Providing information about conceptual limitations is also important for readers to judge the quality of foundations of the research. For example, if you included a mixed-methods study in the review, reporting the methodological and conceptual limitations about ‘integration’ is critical for evaluating the study’s strength. Suppose the authors only collected qualitative and quantitative data and did not state the intent and timing of integration. In that case, the strength of the study is weak. Integration only occurred at the levels of data collection. However, integration may not have occurred at the analysis, interpretation and reporting levels.

Tip 3: write conceptual contribution of each reviewed article

While reading and evaluating review papers, we have observed that many review authors only provide core results of the article included in a review and do not explain the conceptual contribution offered by the included article. We refer to conceptual contribution as a description of how the article’s key results contribute towards the development of potential codes, themes or subthemes, or emerging patterns that are reported as the review findings. For example, the authors of a review article noted that one of the research articles included in their review demonstrated the usefulness of case studies and reflective logs as strategies for fostering compassion in nursing students. The conceptual contribution of this research article could be that experiential learning is one way to teach compassion to nursing students, as supported by case studies and reflective logs. This conceptual contribution of the article should be mentioned in the literature summary table. Delineating each reviewed article’s conceptual contribution is particularly beneficial in qualitative reviews, mixed-methods reviews, and critical reviews that often focus on developing models and describing or explaining various phenomena. Figure 2 offers an example of a literature summary table. 4

Tabular literature summaries from a critical review. Source: Younas and Maddigan. 4

Tip 4: compose potential themes from each article during summary writing

While developing literature summary tables, many authors use themes or subthemes reported in the given articles as the key results of their own review. Such an approach prevents the review authors from understanding the article’s conceptual contribution, developing rigorous synthesis and drawing reasonable interpretations of results from an individual article. Ultimately, it affects the generation of novel review findings. For example, one of the articles about women’s healthcare-seeking behaviours in developing countries reported a theme ‘social-cultural determinants of health as precursors of delays’. Instead of using this theme as one of the review findings, the reviewers should read and interpret beyond the given description in an article, compare and contrast themes, findings from one article with findings and themes from another article to find similarities and differences and to understand and explain bigger picture for their readers. Therefore, while developing literature summary tables, think twice before using the predeveloped themes. Including your themes in the summary tables (see figure 1 ) demonstrates to the readers that a robust method of data extraction and synthesis has been followed.

Tip 5: create your personalised template for literature summaries

Often templates are available for data extraction and development of literature summary tables. The available templates may be in the form of a table, chart or a structured framework that extracts some essential information about every article. The commonly used information may include authors, purpose, methods, key results and quality scores. While extracting all relevant information is important, such templates should be tailored to meet the needs of the individuals’ review. For example, for a review about the effectiveness of healthcare interventions, a literature summary table must include information about the intervention, its type, content timing, duration, setting, effectiveness, negative consequences, and receivers and implementers’ experiences of its usage. Similarly, literature summary tables for articles included in a meta-synthesis must include information about the participants’ characteristics, research context and conceptual contribution of each reviewed article so as to help the reader make an informed decision about the usefulness or lack of usefulness of the individual article in the review and the whole review.

In conclusion, narrative or systematic reviews are almost always conducted as a part of any educational project (thesis or dissertation) or academic or clinical research. Literature reviews are the foundation of research on a given topic. Robust and high-quality reviews play an instrumental role in guiding research, practice and policymaking. However, the quality of reviews is also contingent on rigorous data extraction and synthesis, which require developing literature summaries. We have outlined five tips that could enhance the quality of the data extraction and synthesis process by developing useful literature summaries.

- Aromataris E ,

- Rasheed SP ,

Twitter @Ahtisham04, @parveenazamali

Funding The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests None declared.

Patient consent for publication Not required.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

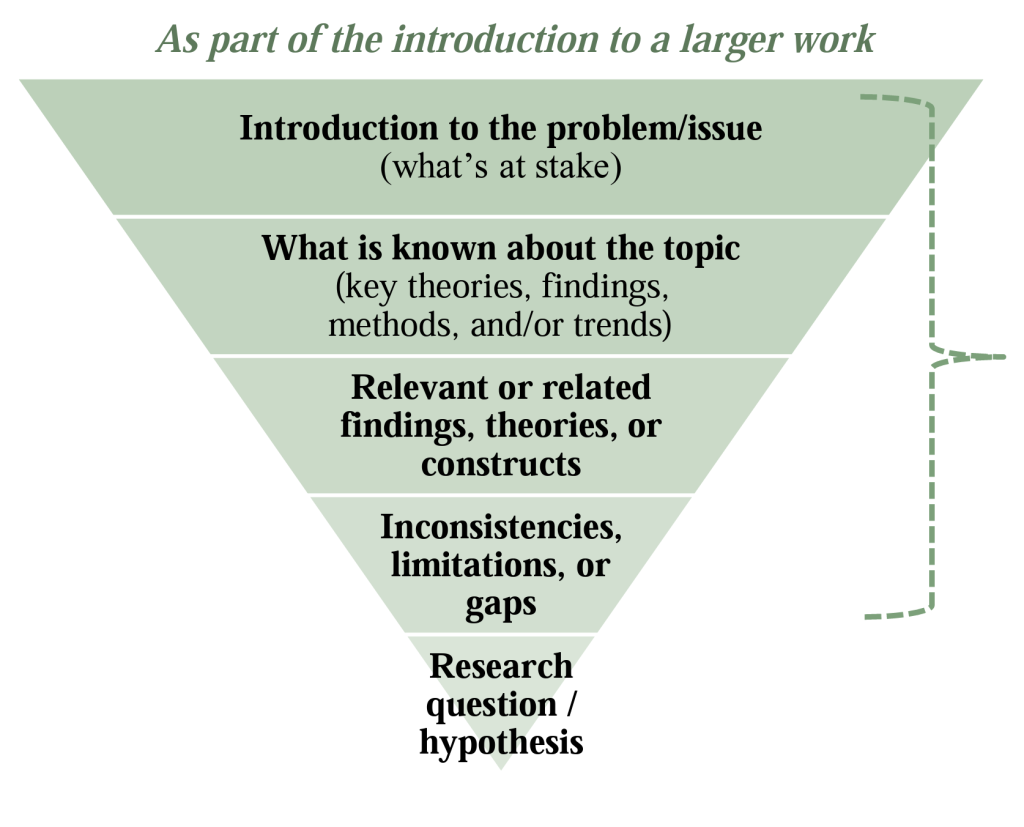

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

Don't submit your assignments before you do this

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students. Free citation check included.

Try for free

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, September 11). How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved August 12, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

Common Assignments: Literature Review Matrix

Literature review matrix.

As you read and evaluate your literature there are several different ways to organize your research. Courtesy of Dr. Gary Burkholder in the School of Psychology, these sample matrices are one option to help organize your articles. These documents allow you to compile details about your sources, such as the foundational theories, methodologies, and conclusions; begin to note similarities among the authors; and retrieve citation information for easy insertion within a document.

You can review the sample matrixes to see a completed form or download the blank matrix for your own use.

- Literature Review Matrix 1 This PDF file provides a sample literature review matrix.

- Literature Review Matrix 2 This PDF file provides a sample literature review matrix.

- Literature Review Matrix Template (Word)

- Literature Review Matrix Template (Excel)

Related Resources

Didn't find what you need? Email us at [email protected] .

- Previous Page: Commentary Versus Opinion

- Next Page: Professional Development Plans (PDPs)

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

What is a Literature Review? How to Write It (with Examples)

A literature review is a critical analysis and synthesis of existing research on a particular topic. It provides an overview of the current state of knowledge, identifies gaps, and highlights key findings in the literature. 1 The purpose of a literature review is to situate your own research within the context of existing scholarship, demonstrating your understanding of the topic and showing how your work contributes to the ongoing conversation in the field. Learning how to write a literature review is a critical tool for successful research. Your ability to summarize and synthesize prior research pertaining to a certain topic demonstrates your grasp on the topic of study, and assists in the learning process.

Table of Contents

- What is the purpose of literature review?

- a. Habitat Loss and Species Extinction:

- b. Range Shifts and Phenological Changes:

- c. Ocean Acidification and Coral Reefs:

- d. Adaptive Strategies and Conservation Efforts:

How to write a good literature review

- Choose a Topic and Define the Research Question:

- Decide on the Scope of Your Review:

- Select Databases for Searches:

- Conduct Searches and Keep Track:

- Review the Literature:

- Organize and Write Your Literature Review:

- How to write a literature review faster with Paperpal?

- Frequently asked questions

What is a literature review?

A well-conducted literature review demonstrates the researcher’s familiarity with the existing literature, establishes the context for their own research, and contributes to scholarly conversations on the topic. One of the purposes of a literature review is also to help researchers avoid duplicating previous work and ensure that their research is informed by and builds upon the existing body of knowledge.

What is the purpose of literature review?

A literature review serves several important purposes within academic and research contexts. Here are some key objectives and functions of a literature review: 2

1. Contextualizing the Research Problem: The literature review provides a background and context for the research problem under investigation. It helps to situate the study within the existing body of knowledge.

2. Identifying Gaps in Knowledge: By identifying gaps, contradictions, or areas requiring further research, the researcher can shape the research question and justify the significance of the study. This is crucial for ensuring that the new research contributes something novel to the field.

Find academic papers related to your research topic faster. Try Research on Paperpal

3. Understanding Theoretical and Conceptual Frameworks: Literature reviews help researchers gain an understanding of the theoretical and conceptual frameworks used in previous studies. This aids in the development of a theoretical framework for the current research.

4. Providing Methodological Insights: Another purpose of literature reviews is that it allows researchers to learn about the methodologies employed in previous studies. This can help in choosing appropriate research methods for the current study and avoiding pitfalls that others may have encountered.

5. Establishing Credibility: A well-conducted literature review demonstrates the researcher’s familiarity with existing scholarship, establishing their credibility and expertise in the field. It also helps in building a solid foundation for the new research.

6. Informing Hypotheses or Research Questions: The literature review guides the formulation of hypotheses or research questions by highlighting relevant findings and areas of uncertainty in existing literature.

Literature review example

Let’s delve deeper with a literature review example: Let’s say your literature review is about the impact of climate change on biodiversity. You might format your literature review into sections such as the effects of climate change on habitat loss and species extinction, phenological changes, and marine biodiversity. Each section would then summarize and analyze relevant studies in those areas, highlighting key findings and identifying gaps in the research. The review would conclude by emphasizing the need for further research on specific aspects of the relationship between climate change and biodiversity. The following literature review template provides a glimpse into the recommended literature review structure and content, demonstrating how research findings are organized around specific themes within a broader topic.

Literature Review on Climate Change Impacts on Biodiversity:

Climate change is a global phenomenon with far-reaching consequences, including significant impacts on biodiversity. This literature review synthesizes key findings from various studies:

a. Habitat Loss and Species Extinction:

Climate change-induced alterations in temperature and precipitation patterns contribute to habitat loss, affecting numerous species (Thomas et al., 2004). The review discusses how these changes increase the risk of extinction, particularly for species with specific habitat requirements.

b. Range Shifts and Phenological Changes:

Observations of range shifts and changes in the timing of biological events (phenology) are documented in response to changing climatic conditions (Parmesan & Yohe, 2003). These shifts affect ecosystems and may lead to mismatches between species and their resources.

c. Ocean Acidification and Coral Reefs:

The review explores the impact of climate change on marine biodiversity, emphasizing ocean acidification’s threat to coral reefs (Hoegh-Guldberg et al., 2007). Changes in pH levels negatively affect coral calcification, disrupting the delicate balance of marine ecosystems.

d. Adaptive Strategies and Conservation Efforts:

Recognizing the urgency of the situation, the literature review discusses various adaptive strategies adopted by species and conservation efforts aimed at mitigating the impacts of climate change on biodiversity (Hannah et al., 2007). It emphasizes the importance of interdisciplinary approaches for effective conservation planning.

Strengthen your literature review with factual insights. Try Research on Paperpal for free!

Writing a literature review involves summarizing and synthesizing existing research on a particular topic. A good literature review format should include the following elements.

Introduction: The introduction sets the stage for your literature review, providing context and introducing the main focus of your review.

- Opening Statement: Begin with a general statement about the broader topic and its significance in the field.

- Scope and Purpose: Clearly define the scope of your literature review. Explain the specific research question or objective you aim to address.

- Organizational Framework: Briefly outline the structure of your literature review, indicating how you will categorize and discuss the existing research.

- Significance of the Study: Highlight why your literature review is important and how it contributes to the understanding of the chosen topic.

- Thesis Statement: Conclude the introduction with a concise thesis statement that outlines the main argument or perspective you will develop in the body of the literature review.

Body: The body of the literature review is where you provide a comprehensive analysis of existing literature, grouping studies based on themes, methodologies, or other relevant criteria.

- Organize by Theme or Concept: Group studies that share common themes, concepts, or methodologies. Discuss each theme or concept in detail, summarizing key findings and identifying gaps or areas of disagreement.

- Critical Analysis: Evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of each study. Discuss the methodologies used, the quality of evidence, and the overall contribution of each work to the understanding of the topic.

- Synthesis of Findings: Synthesize the information from different studies to highlight trends, patterns, or areas of consensus in the literature.

- Identification of Gaps: Discuss any gaps or limitations in the existing research and explain how your review contributes to filling these gaps.

- Transition between Sections: Provide smooth transitions between different themes or concepts to maintain the flow of your literature review.

Write and Cite as you go with Paperpal Research. Start now for free.

Conclusion: The conclusion of your literature review should summarize the main findings, highlight the contributions of the review, and suggest avenues for future research.

- Summary of Key Findings: Recap the main findings from the literature and restate how they contribute to your research question or objective.

- Contributions to the Field: Discuss the overall contribution of your literature review to the existing knowledge in the field.

- Implications and Applications: Explore the practical implications of the findings and suggest how they might impact future research or practice.

- Recommendations for Future Research: Identify areas that require further investigation and propose potential directions for future research in the field.

- Final Thoughts: Conclude with a final reflection on the importance of your literature review and its relevance to the broader academic community.

Conducting a literature review

Conducting a literature review is an essential step in research that involves reviewing and analyzing existing literature on a specific topic. It’s important to know how to do a literature review effectively, so here are the steps to follow: 1

Choose a Topic and Define the Research Question:

- Select a topic that is relevant to your field of study.

- Clearly define your research question or objective. Determine what specific aspect of the topic do you want to explore?

Decide on the Scope of Your Review:

- Determine the timeframe for your literature review. Are you focusing on recent developments, or do you want a historical overview?

- Consider the geographical scope. Is your review global, or are you focusing on a specific region?

- Define the inclusion and exclusion criteria. What types of sources will you include? Are there specific types of studies or publications you will exclude?

Select Databases for Searches:

- Identify relevant databases for your field. Examples include PubMed, IEEE Xplore, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar.

- Consider searching in library catalogs, institutional repositories, and specialized databases related to your topic.

Conduct Searches and Keep Track:

- Develop a systematic search strategy using keywords, Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT), and other search techniques.

- Record and document your search strategy for transparency and replicability.

- Keep track of the articles, including publication details, abstracts, and links. Use citation management tools like EndNote, Zotero, or Mendeley to organize your references.

Review the Literature:

- Evaluate the relevance and quality of each source. Consider the methodology, sample size, and results of studies.

- Organize the literature by themes or key concepts. Identify patterns, trends, and gaps in the existing research.

- Summarize key findings and arguments from each source. Compare and contrast different perspectives.

- Identify areas where there is a consensus in the literature and where there are conflicting opinions.

- Provide critical analysis and synthesis of the literature. What are the strengths and weaknesses of existing research?

Organize and Write Your Literature Review:

- Literature review outline should be based on themes, chronological order, or methodological approaches.

- Write a clear and coherent narrative that synthesizes the information gathered.

- Use proper citations for each source and ensure consistency in your citation style (APA, MLA, Chicago, etc.).

- Conclude your literature review by summarizing key findings, identifying gaps, and suggesting areas for future research.

Whether you’re exploring a new research field or finding new angles to develop an existing topic, sifting through hundreds of papers can take more time than you have to spare. But what if you could find science-backed insights with verified citations in seconds? That’s the power of Paperpal’s new Research feature!

How to write a literature review faster with Paperpal?

Paperpal, an AI writing assistant, integrates powerful academic search capabilities within its writing platform. With the Research feature, you get 100% factual insights, with citations backed by 250M+ verified research articles, directly within your writing interface with the option to save relevant references in your Citation Library. By eliminating the need to switch tabs to find answers to all your research questions, Paperpal saves time and helps you stay focused on your writing.

Here’s how to use the Research feature:

- Ask a question: Get started with a new document on paperpal.com. Click on the “Research” feature and type your question in plain English. Paperpal will scour over 250 million research articles, including conference papers and preprints, to provide you with accurate insights and citations.

- Review and Save: Paperpal summarizes the information, while citing sources and listing relevant reads. You can quickly scan the results to identify relevant references and save these directly to your built-in citations library for later access.

- Cite with Confidence: Paperpal makes it easy to incorporate relevant citations and references into your writing, ensuring your arguments are well-supported by credible sources. This translates to a polished, well-researched literature review.

The literature review sample and detailed advice on writing and conducting a review will help you produce a well-structured report. But remember that a good literature review is an ongoing process, and it may be necessary to revisit and update it as your research progresses. By combining effortless research with an easy citation process, Paperpal Research streamlines the literature review process and empowers you to write faster and with more confidence. Try Paperpal Research now and see for yourself.

Frequently asked questions

A literature review is a critical and comprehensive analysis of existing literature (published and unpublished works) on a specific topic or research question and provides a synthesis of the current state of knowledge in a particular field. A well-conducted literature review is crucial for researchers to build upon existing knowledge, avoid duplication of efforts, and contribute to the advancement of their field. It also helps researchers situate their work within a broader context and facilitates the development of a sound theoretical and conceptual framework for their studies.

Literature review is a crucial component of research writing, providing a solid background for a research paper’s investigation. The aim is to keep professionals up to date by providing an understanding of ongoing developments within a specific field, including research methods, and experimental techniques used in that field, and present that knowledge in the form of a written report. Also, the depth and breadth of the literature review emphasizes the credibility of the scholar in his or her field.

Before writing a literature review, it’s essential to undertake several preparatory steps to ensure that your review is well-researched, organized, and focused. This includes choosing a topic of general interest to you and doing exploratory research on that topic, writing an annotated bibliography, and noting major points, especially those that relate to the position you have taken on the topic.

Literature reviews and academic research papers are essential components of scholarly work but serve different purposes within the academic realm. 3 A literature review aims to provide a foundation for understanding the current state of research on a particular topic, identify gaps or controversies, and lay the groundwork for future research. Therefore, it draws heavily from existing academic sources, including books, journal articles, and other scholarly publications. In contrast, an academic research paper aims to present new knowledge, contribute to the academic discourse, and advance the understanding of a specific research question. Therefore, it involves a mix of existing literature (in the introduction and literature review sections) and original data or findings obtained through research methods.

Literature reviews are essential components of academic and research papers, and various strategies can be employed to conduct them effectively. If you want to know how to write a literature review for a research paper, here are four common approaches that are often used by researchers. Chronological Review: This strategy involves organizing the literature based on the chronological order of publication. It helps to trace the development of a topic over time, showing how ideas, theories, and research have evolved. Thematic Review: Thematic reviews focus on identifying and analyzing themes or topics that cut across different studies. Instead of organizing the literature chronologically, it is grouped by key themes or concepts, allowing for a comprehensive exploration of various aspects of the topic. Methodological Review: This strategy involves organizing the literature based on the research methods employed in different studies. It helps to highlight the strengths and weaknesses of various methodologies and allows the reader to evaluate the reliability and validity of the research findings. Theoretical Review: A theoretical review examines the literature based on the theoretical frameworks used in different studies. This approach helps to identify the key theories that have been applied to the topic and assess their contributions to the understanding of the subject. It’s important to note that these strategies are not mutually exclusive, and a literature review may combine elements of more than one approach. The choice of strategy depends on the research question, the nature of the literature available, and the goals of the review. Additionally, other strategies, such as integrative reviews or systematic reviews, may be employed depending on the specific requirements of the research.

The literature review format can vary depending on the specific publication guidelines. However, there are some common elements and structures that are often followed. Here is a general guideline for the format of a literature review: Introduction: Provide an overview of the topic. Define the scope and purpose of the literature review. State the research question or objective. Body: Organize the literature by themes, concepts, or chronology. Critically analyze and evaluate each source. Discuss the strengths and weaknesses of the studies. Highlight any methodological limitations or biases. Identify patterns, connections, or contradictions in the existing research. Conclusion: Summarize the key points discussed in the literature review. Highlight the research gap. Address the research question or objective stated in the introduction. Highlight the contributions of the review and suggest directions for future research.

Both annotated bibliographies and literature reviews involve the examination of scholarly sources. While annotated bibliographies focus on individual sources with brief annotations, literature reviews provide a more in-depth, integrated, and comprehensive analysis of existing literature on a specific topic. The key differences are as follows:

| Annotated Bibliography | Literature Review | |

| Purpose | List of citations of books, articles, and other sources with a brief description (annotation) of each source. | Comprehensive and critical analysis of existing literature on a specific topic. |

| Focus | Summary and evaluation of each source, including its relevance, methodology, and key findings. | Provides an overview of the current state of knowledge on a particular subject and identifies gaps, trends, and patterns in existing literature. |

| Structure | Each citation is followed by a concise paragraph (annotation) that describes the source’s content, methodology, and its contribution to the topic. | The literature review is organized thematically or chronologically and involves a synthesis of the findings from different sources to build a narrative or argument. |

| Length | Typically 100-200 words | Length of literature review ranges from a few pages to several chapters |

| Independence | Each source is treated separately, with less emphasis on synthesizing the information across sources. | The writer synthesizes information from multiple sources to present a cohesive overview of the topic. |

References

- Denney, A. S., & Tewksbury, R. (2013). How to write a literature review. Journal of criminal justice education , 24 (2), 218-234.

- Pan, M. L. (2016). Preparing literature reviews: Qualitative and quantitative approaches . Taylor & Francis.

- Cantero, C. (2019). How to write a literature review. San José State University Writing Center .

Paperpal is an AI writing assistant that help academics write better, faster with real-time suggestions for in-depth language and grammar correction. Trained on millions of research manuscripts enhanced by professional academic editors, Paperpal delivers human precision at machine speed.

Try it for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime , which unlocks unlimited access to premium features like academic translation, paraphrasing, contextual synonyms, consistency checks and more. It’s like always having a professional academic editor by your side! Go beyond limitations and experience the future of academic writing. Get Paperpal Prime now at just US$19 a month!

Related Reads:

- Empirical Research: A Comprehensive Guide for Academics

- How to Write a Scientific Paper in 10 Steps

- How Long Should a Chapter Be?

- How to Use Paperpal to Generate Emails & Cover Letters?

6 Tips for Post-Doc Researchers to Take Their Career to the Next Level

Self-plagiarism in research: what it is and how to avoid it, you may also like, the ai revolution: authors’ role in upholding academic..., the future of academia: how ai tools are..., how to write a research proposal: (with examples..., how to write your research paper in apa..., how to choose a dissertation topic, how to write a phd research proposal, how to write an academic paragraph (step-by-step guide), five things authors need to know when using..., 7 best referencing tools and citation management software..., maintaining academic integrity with paperpal’s generative ai writing....

- Linguistics

- Composition Studies

Five tips for developing useful literature summary tables for writing review articles

- Evidence-Based Nursing 24(2)

- Memorial University of Newfoundland

- The University of Sheffield

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

- Heart Lung Circ

- Alyne Santos Borges

- Paola Pugian Jardim

- Pearse McCusker

- Hamzah Shahid Rafiq

- Creativ Nurs

- Richard Booth

- Bethany Jackson

- Esther Weir

- Jonathan Mead

- Maryanna Cruz da Costa e Silva Andrade

- Juliana de Melo Vellozo Pereira Tinoco

- Isabelle Andrade Silveira

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

Literature Review Basics

- What is a Literature Review?

- Synthesizing Research

- Using Research & Synthesis Tables

- Additional Resources

About the Research and Synthesis Tables

Research Tables and Synthesis Tables are useful tools for organizing and analyzing your research as you assemble your literature review. They represent two different parts of the review process: assembling relevant information and synthesizing it. Use a Research table to compile the main info you need about the items you find in your research -- it's a great thing to have on hand as you take notes on what you read! Then, once you've assembled your research, use the Synthesis table to start charting the similarities/differences and major themes among your collected items.

We've included an Excel file with templates for you to use below; the examples pictured on this page are snapshots from that file.

- Research and Synthesis Table Templates This Excel workbook includes simple templates for creating research tables and synthesis tables. Feel free to download and use!

Using the Research Table

This is an example of a research table, in which you provide a basic description of the most important features of the studies, articles, and other items you discover in your research. The table identifies each item according to its author/date of publication, its purpose or thesis, what type of work it is (systematic review, clinical trial, etc.), the level of evidence it represents (which tells you a lot about its impact on the field of study), and its major findings. Your job, when you assemble this information, is to develop a snapshot of what the research shows about the topic of your research question and assess its value (both for the purpose of your work and for general knowledge in the field).

Think of your work on the research table as the foundational step for your analysis of the literature, in which you assemble the information you'll be analyzing and lay the groundwork for thinking about what it means and how it can be used.

Using the Synthesis Table

This is an example of a synthesis table or synthesis matrix , in which you organize and analyze your research by listing each source and indicating whether a given finding or result occurred in a particular study or article ( each row lists an individual source, and each finding has its own column, in which X = yes, blank = no). You can also add or alter the columns to look for shared study populations, sort by level of evidence or source type, etc. The key here is to use the table to provide a simple representation of what the research has found (or not found, as the case may be). Think of a synthesis table as a tool for making comparisons, identifying trends, and locating gaps in the literature.

How do I know which findings to use, or how many to include? Your research question tells you which findings are of interest in your research, so work from your research question to decide what needs to go in each Finding header, and how many findings are necessary. The number is up to you; again, you can alter this table by adding or deleting columns to match what you're actually looking for in your analysis. You should also, of course, be guided by what's actually present in the material your research turns up!

- << Previous: Synthesizing Research

- Next: Additional Resources >>

- Last Updated: Sep 26, 2023 12:06 PM

- URL: https://usi.libguides.com/literature-review-basics

- Reserve a study room

- Library Account

- Undergraduate Students

- Graduate Students

- Faculty & Staff

How to Conduct a Literature Review (Health Sciences and Beyond)

- What is a Literature Review?

- Developing a Research Question

- Selection Criteria

- Database Search

- Documenting Your Search

Review Matrix

- Reference Management

Using a spreadsheet or table to organize the key elements (e.g. subjects, methodologies, results) of articles/books you plan to use in your literature review can be helpful. This is called a review matrix.

When you create a review matrix, the first few columns should include (1) the authors, title, journal, (2) publication year, and (3) purpose of the paper. The remaining columns should identify important aspects of each study such as methodology and findings.

Click on the image below to view a sample review matrix.

You can also download this template as a Microsoft Excel file .

The information on this page is from the book below. The 5th edition is available online through VCU Libraries.

- << Previous: Documenting Your Search

- Next: Reference Management >>

- Last Updated: Mar 15, 2024 12:22 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.vcu.edu/health-sciences-lit-review

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing a Literature Review

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

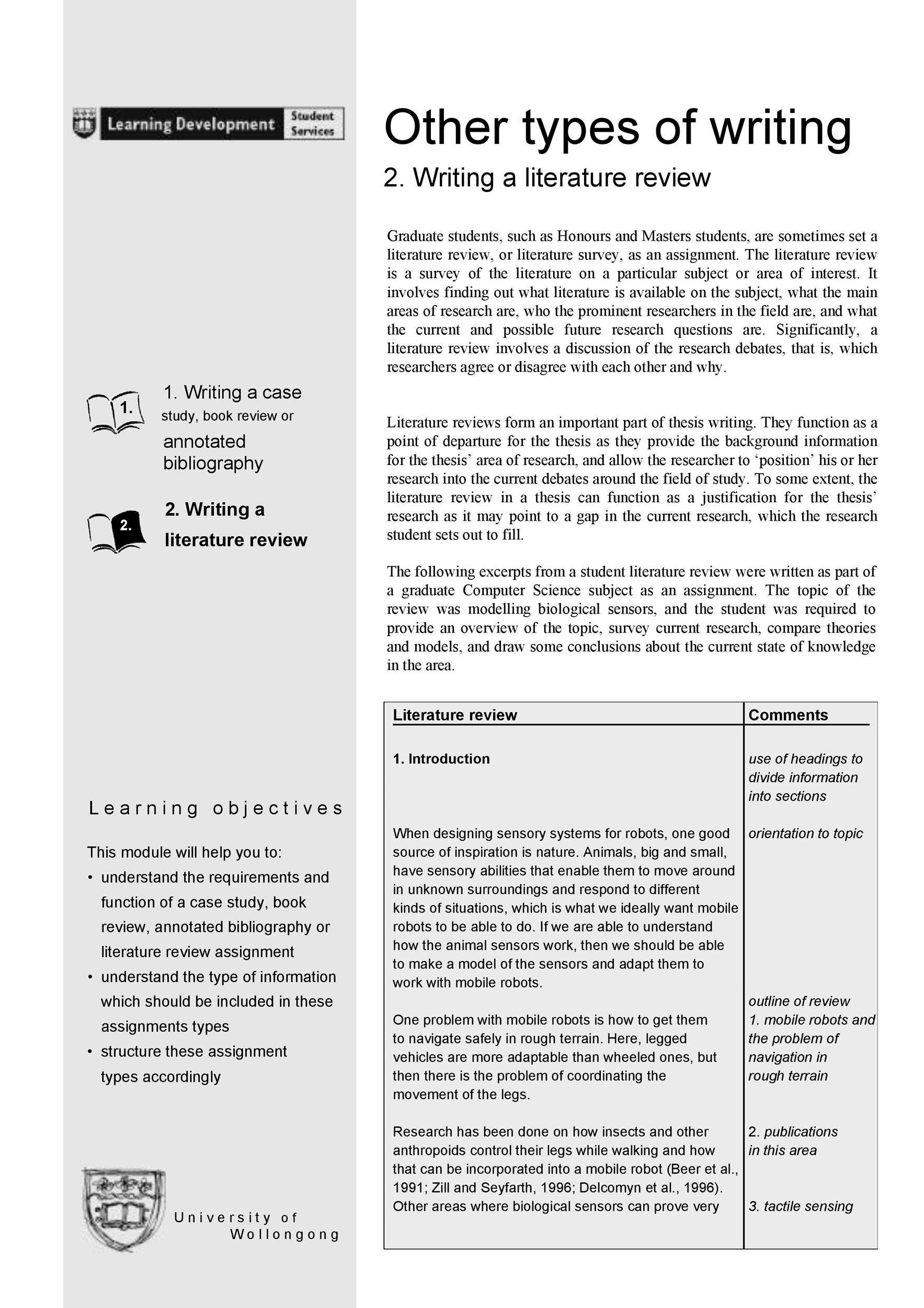

A literature review is a document or section of a document that collects key sources on a topic and discusses those sources in conversation with each other (also called synthesis ). The lit review is an important genre in many disciplines, not just literature (i.e., the study of works of literature such as novels and plays). When we say “literature review” or refer to “the literature,” we are talking about the research ( scholarship ) in a given field. You will often see the terms “the research,” “the scholarship,” and “the literature” used mostly interchangeably.

Where, when, and why would I write a lit review?

There are a number of different situations where you might write a literature review, each with slightly different expectations; different disciplines, too, have field-specific expectations for what a literature review is and does. For instance, in the humanities, authors might include more overt argumentation and interpretation of source material in their literature reviews, whereas in the sciences, authors are more likely to report study designs and results in their literature reviews; these differences reflect these disciplines’ purposes and conventions in scholarship. You should always look at examples from your own discipline and talk to professors or mentors in your field to be sure you understand your discipline’s conventions, for literature reviews as well as for any other genre.

A literature review can be a part of a research paper or scholarly article, usually falling after the introduction and before the research methods sections. In these cases, the lit review just needs to cover scholarship that is important to the issue you are writing about; sometimes it will also cover key sources that informed your research methodology.

Lit reviews can also be standalone pieces, either as assignments in a class or as publications. In a class, a lit review may be assigned to help students familiarize themselves with a topic and with scholarship in their field, get an idea of the other researchers working on the topic they’re interested in, find gaps in existing research in order to propose new projects, and/or develop a theoretical framework and methodology for later research. As a publication, a lit review usually is meant to help make other scholars’ lives easier by collecting and summarizing, synthesizing, and analyzing existing research on a topic. This can be especially helpful for students or scholars getting into a new research area, or for directing an entire community of scholars toward questions that have not yet been answered.

What are the parts of a lit review?

Most lit reviews use a basic introduction-body-conclusion structure; if your lit review is part of a larger paper, the introduction and conclusion pieces may be just a few sentences while you focus most of your attention on the body. If your lit review is a standalone piece, the introduction and conclusion take up more space and give you a place to discuss your goals, research methods, and conclusions separately from where you discuss the literature itself.

Introduction:

- An introductory paragraph that explains what your working topic and thesis is

- A forecast of key topics or texts that will appear in the review

- Potentially, a description of how you found sources and how you analyzed them for inclusion and discussion in the review (more often found in published, standalone literature reviews than in lit review sections in an article or research paper)

- Summarize and synthesize: Give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: Don’t just paraphrase other researchers – add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically Evaluate: Mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: Use transition words and topic sentence to draw connections, comparisons, and contrasts.

Conclusion:

- Summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance

- Connect it back to your primary research question

How should I organize my lit review?

Lit reviews can take many different organizational patterns depending on what you are trying to accomplish with the review. Here are some examples:

- Chronological : The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time, which helps familiarize the audience with the topic (for instance if you are introducing something that is not commonly known in your field). If you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order. Try to analyze the patterns, turning points, and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred (as mentioned previously, this may not be appropriate in your discipline — check with a teacher or mentor if you’re unsure).

- Thematic : If you have found some recurring central themes that you will continue working with throughout your piece, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic. For example, if you are reviewing literature about women and religion, key themes can include the role of women in churches and the religious attitude towards women.

- Qualitative versus quantitative research

- Empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the research by sociological, historical, or cultural sources

- Theoretical : In many humanities articles, the literature review is the foundation for the theoretical framework. You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts. You can argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach or combine various theorical concepts to create a framework for your research.

What are some strategies or tips I can use while writing my lit review?

Any lit review is only as good as the research it discusses; make sure your sources are well-chosen and your research is thorough. Don’t be afraid to do more research if you discover a new thread as you’re writing. More info on the research process is available in our "Conducting Research" resources .

As you’re doing your research, create an annotated bibliography ( see our page on the this type of document ). Much of the information used in an annotated bibliography can be used also in a literature review, so you’ll be not only partially drafting your lit review as you research, but also developing your sense of the larger conversation going on among scholars, professionals, and any other stakeholders in your topic.

Usually you will need to synthesize research rather than just summarizing it. This means drawing connections between sources to create a picture of the scholarly conversation on a topic over time. Many student writers struggle to synthesize because they feel they don’t have anything to add to the scholars they are citing; here are some strategies to help you:

- It often helps to remember that the point of these kinds of syntheses is to show your readers how you understand your research, to help them read the rest of your paper.

- Writing teachers often say synthesis is like hosting a dinner party: imagine all your sources are together in a room, discussing your topic. What are they saying to each other?

- Look at the in-text citations in each paragraph. Are you citing just one source for each paragraph? This usually indicates summary only. When you have multiple sources cited in a paragraph, you are more likely to be synthesizing them (not always, but often

- Read more about synthesis here.

The most interesting literature reviews are often written as arguments (again, as mentioned at the beginning of the page, this is discipline-specific and doesn’t work for all situations). Often, the literature review is where you can establish your research as filling a particular gap or as relevant in a particular way. You have some chance to do this in your introduction in an article, but the literature review section gives a more extended opportunity to establish the conversation in the way you would like your readers to see it. You can choose the intellectual lineage you would like to be part of and whose definitions matter most to your thinking (mostly humanities-specific, but this goes for sciences as well). In addressing these points, you argue for your place in the conversation, which tends to make the lit review more compelling than a simple reporting of other sources.

The Sheridan Libraries

- Write a Literature Review

- Sheridan Libraries

- Evaluate This link opens in a new window

Get Organized

- Lit Review Prep Use this template to help you evaluate your sources, create article summaries for an annotated bibliography, and a synthesis matrix for your lit review outline.

Synthesize your Information

Synthesize: combine separate elements to form a whole.

Synthesis Matrix

A synthesis matrix helps you record the main points of each source and document how sources relate to each other.

After summarizing and evaluating your sources, arrange them in a matrix or use a citation manager to help you see how they relate to each other and apply to each of your themes or variables.

By arranging your sources by theme or variable, you can see how your sources relate to each other, and can start thinking about how you weave them together to create a narrative.

- Step-by-Step Approach

- Example Matrix from NSCU

- Matrix Template

- << Previous: Summarize

- Next: Integrate >>

- Last Updated: Jul 30, 2024 1:42 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.jhu.edu/lit-review

- University of Oregon Libraries

- Research Guides

How to Write a Literature Review

- 6. Synthesize

- Literature Reviews: A Recap

- Reading Journal Articles

- Does it Describe a Literature Review?

- 1. Identify the Question

- 2. Review Discipline Styles

- Searching Article Databases

- Finding Full-Text of an Article

- Citation Chaining

- When to Stop Searching

- 4. Manage Your References

- 5. Critically Analyze and Evaluate

Synthesis Visualization

Synthesis matrix example.

- 7. Write a Literature Review

- Synthesis Worksheet

About Synthesis

| What is synthesis? | What synthesis is NOT: |

|---|---|

Approaches to Synthesis

You can sort the literature in various ways, for example:

How to Begin?

Read your sources carefully and find the main idea(s) of each source

Look for similarities in your sources – which sources are talking about the same main ideas? (for example, sources that discuss the historical background on your topic)

Use the worksheet (above) or synthesis matrix (below) to get organized

This work can be messy. Don't worry if you have to go through a few iterations of the worksheet or matrix as you work on your lit review!

Four Examples of Student Writing

In the four examples below, only ONE shows a good example of synthesis: the fourth column, or Student D . For a web accessible version, click the link below the image.

Long description of "Four Examples of Student Writing" for web accessibility

- Download a copy of the "Four Examples of Student Writing" chart

Click on the example to view the pdf.

From Jennifer Lim

- << Previous: 5. Critically Analyze and Evaluate

- Next: 7. Write a Literature Review >>

- Last Updated: Aug 12, 2024 11:48 AM

- URL: https://researchguides.uoregon.edu/litreview

Contact Us Library Accessibility UO Libraries Privacy Notices and Procedures

1501 Kincaid Street Eugene, OR 97403 P: 541-346-3053 F: 541-346-3485

- Visit us on Facebook

- Visit us on Twitter

- Visit us on Youtube

- Visit us on Instagram

- Report a Concern

- Nondiscrimination and Title IX

- Accessibility

- Privacy Policy

- Find People

Free Download

Literature Review Template

The fastest (and smartest) way to craft a strong literature review that lays a solid theoretical foundation and earns marks.

Available in Google Doc, Word & PDF format 4.9 star rating, 5000 + downloads

Step-by-step instructions

Tried & tested academic format

Fill-in-the-blanks simplicity

Pro tips, tricks and resources

What It Covers

This literature review template is based on the tried and trusted best-practice format and structure for formal academic research projects. It includes the following sections:

- Before you start – essential groundwork to ensure you’re ready

- The introduction section

- The core/body section

- The conclusion /summary

- Extra free resources

Each section is explained in plain, straightforward language , followed by an overview of the key elements. We’ve also included practical examples and links to free videos to help you understand what’s required in each section.

The template can be copied to your Google Drive 0r downloaded as a fully editable MS Word Document (DOCX format), adaptable to LaTeX.

download your copy now

100% Free to use. Instant access.

I agree to receive the free template and other useful resources.

Download Now (Instant Access)

FAQs: Literature Review Template

What format is the template (doc, pdf, ppt, etc.).

The literature review chapter template is provided as a Google Doc. You can download it in MS Word format or make a copy to your Google Drive. You’re also welcome to convert it to whatever format works best for you, such as LaTeX or PDF.

What types of literature reviews can this template be used for?

The template follows the standard format for academic literature reviews, which means it will be suitable for the vast majority of academic research projects (especially those within the sciences), whether they are qualitative or quantitative in terms of design.

Keep in mind that the exact requirements for the literature review chapter will vary between universities and degree programs. These are typically minor, but it’s always a good idea to double-check your university’s requirements before you finalize your structure.

Is this template for an undergrad, Master or PhD-level thesis?

This template can be used for a literature review at any level of study. Doctoral-level projects typically require the literature review to be more extensive/comprehensive, but the structure will typically remain the same.

Can I modify the template to suit my topic/area?

Absolutely. While the template provides a general structure, you should adapt it to fit the specific requirements and focus of your literature review.

What structural style does this literature review template use?

The template assumes a thematic structure (as opposed to a chronological or methodological structure), as this is the most common approach. However, this is only one dimension of the template, so it will still be useful if you are adopting a different structure.

Does this template include the Excel literature catalog?

No, that is a separate template, which you can download for free here . This template is for the write-up of the actual literature review chapter, whereas the catalog is for use during the literature sourcing and sorting phase.

How long should the literature review chapter be?

This depends on your university’s specific requirements, so it’s best to check with them. As a general ballpark, literature reviews for Masters-level projects are usually 2,000 – 3,000 words in length, while Doctoral-level projects can reach multiples of this.

Can I include literature that contradicts my hypothesis?

Yes, it’s important to acknowledge and discuss literature that presents different viewpoints or contradicts your hypothesis. So, don’t shy away from existing research that takes an opposing view to yours.

How do I avoid plagiarism in my literature review?

Always cite your sources correctly and paraphrase ideas in your own words while maintaining the original meaning. You can always check our plagiarism score before submitting your work to help ease your mind.

Do you have an example of a populated template?

We provide a walkthrough of the template and review an example of a high-quality literature research chapter here .

Can I share this literature review template with my friends/colleagues?

Yes, you’re welcome to share this template in its original format (no editing allowed). If you want to post about it on your blog or social media, all we ask is that you reference this page as your source.

Do you have templates for the other dissertation/thesis chapters?

Yes, we do. You can find our full collection of templates here .

Can Grad Coach help me with my literature review?

Yes, you’re welcome to get in touch with us to discuss our private coaching services , where we can help you work through the literature review chapter (and any other chapters).

Additional Resources

If you’re working on a literature review, you’ll also want to check these out…

Literature Review Bootcamp

1-On-1 Private Coaching

The Grad Coach YouTube Channel

The Grad Coach Podcast

- Dissertation & Thesis Guides

- Basics of Dissertation & Thesis Writing

- How to Write a Literature Review for Research: Guide, Structure & Template Examples

- Speech Topics

- Basics of Essay Writing

- Essay Topics

- Other Essays

- Main Academic Essays

- Research Paper Topics

- Basics of Research Paper Writing

- Miscellaneous

- Chicago/ Turabian

- Data & Statistics

- Methodology

- Admission Writing Tips

- Admission Advice

- Other Guides

- Student Life

- Studying Tips

- Understanding Plagiarism

- Academic Writing Tips

- Essay Guides

- Research Paper Guides

- Formatting Guides

- Basics of Research Process

- Admission Guides

How to Write a Literature Review for Research: Guide, Structure & Template Examples

Table of contents

Use our free Readability checker

A literature review is a critical analysis of published research on a particular topic. It involves reviewing and analyzing a range of sources, such as academic articles, books, and reports. Students conduct a literature review before writing a research paper or dissertation to gain an understanding of the existing knowledge and recognize areas for further exploration.

Evaluating scholarly works is a crucial aspect of academic work because it establishes the foundation for an inquiry and uncovers new information or gaps in studies. Thus, it is essential to develop and structure it correctly. In this guide you will find:

- A detailed definition

- Elements of a good literary review

- How to do a literature review

- Examples of literature review template.

Read on to explore the structure and straightforward steps for assessing existing sources on your topic. In case you are looking for a quick solution, consider giving our literature review services a try.

What Is a Literature Review: Definition