Learning Corner

- Where Do I Start?

- All Worksheets

- Improve Performance

- Manage & Make Time

- Procrasti-NOT

- Works Cited/Referenced/Researched

- Remote & Online Learning

- Less Stress

- How-To Videos

You are here

Reading strategies & tips.

Reading is a foundational learning activity for college-level courses. Assigned readings prepare you for taking notes during lectures and provide you with additional examples and detail that might not be covered in class. Also, according to research, readings are the second most frequent source of exam questions (Cuseo, Fecas & Thompson, 2007).

Reading a college textbook effectively takes practice and should be approached differently than reading a novel, comic book, magazine, or website. Becoming an effective reader goes beyond completing the reading in full or highlighting text. There are a variety of strategies you can use to read effectively and retain the information you read.

Consider the following quick tips and ideas to make the most of your reading time:

- Schedule time to read . Reading is an easy thing to put off because there is often no exact due date. By scheduling a time each week to do your reading for each class, you are more likely to complete the reading as if it were an assignment. Producing a study guide or set of notes from the reading can help to direct your thinking as you read.

- Set yourself up for success . Pick a location that is conducive to reading. Establish a reasonable goal for the reading, and a time limit for how long you’ll be working. These techniques make reading feel manageable and make it easier to get started and finish reading.

- Choose and use a specific reading strategy . There are many strategies that will help you actively read and retain information (PRR or SQ3R – see the handouts and videos). By consciously choosing a way to approach your reading, you can begin the first step of exam preparation or essay writing. Remember: good readers make stronger writers.

- Monitor your comprehension . When you finish a section, ask yourself, "What is the main idea in this section? Could I answer an exam question about this topic?" Questions at the end of chapters are particularly good for focusing your attention and for assessing your comprehension. If you are having difficulty recalling information or answering questions about the text, search back through the text and look for key points and answers. Self-correction techniques like revisiting the text are essential to assessing your comprehension and are a hallmark technique of advanced readers (Caverly & Orlando, 1991).

- Take notes as you read . Whether they’re annotations in the margins of the book, or notes on a separate piece of paper. Engage with the reading through your notes – ask questions, answer questions, make connections, and think about how these ideas integrate with other information sources (like lecture, lab, other readings, etc.)

Want to dive in a little deeper? Take a look at Kathleen King's tips below to help you get the most out of your reading, and to read for success. You'll see that some are similar to the tips above, but some offer new approaches and ideas; see what works for you:

- Read sitting up with good light, and at a desk or table.

- Keep background noise to a minimum . Loud rock music will not make you a better reader. The same goes for other distractions: talking to roommates, kids playing nearby, television or radio. Give yourself a quiet environment so that you can concentrate on the text.

- Keep paper and pen within reach .

- Before beginning to read, think about the purpose of the reading . Why has the teacher assigned the reading? What are you supposed to get out of it? Jot down your thoughts.

- Survey the reading . Look at the title of the piece, the subheadings. What is in the dark print or stands out? Are there illustrations or graphs?

- Strategize your approach : read the introduction and conclusion, then go back and read the whole assignment, or read the first line in every paragraph to get an idea of how the ideas progress, then go back and read from the beginning.

- Scan effectively : scan the entire reading, and then focus on the most interesting or relevant parts to read in detail.

- Get a feel for what's expected of you by the reading . Pay attention to when you can skim and when you need to understand every word.

- Write as you read . Take notes and talk back to the text. Explain in detail the concepts. Mark up the pages. Ask questions. Write possible test questions. Write down what interests or bores you. Speculate about why.

- If you get stuck : think and write about where you got stuck. Contemplate why that particular place was difficult and how you might break through the block.

- Record and explore your confusion . Confusion is important because it’s the first stage in understanding.

- When the going gets difficult, and you don’t understand the reading , slow down and reread sections. Try to explain them to someone, or have someone else read the section and talk through it together.

- Break long assignments into segments . Read 10 pages (and take notes) then do something else. Later, read the next 10 pages and so on.

- Read prefaces and summaries to learn important details about the book. Look at the table of contents for information about the structure and movement of ideas. Use the index to look up specific names, places, ideas.

(Reading strategies by Dr. Kathleen King. Many of the above ideas are from a lecture by Dr. Lee Haugen, former Reading specialist at the ISU Academic Skills Center. https://www.ghc.edu/sites/default/files/StudentResources/documents/learn... )

Curious to learn more? Check out our Reading video , and hear what we have to say!

WE'RE HERE TO HELP:

Summer Hours Drop In: Wednesdays, 10am to 4pm PST 125 Waldo Hall Our drop-in space will be closed on Wednesday, June 19th for Juneteenth.

Call or Email: Mon-Fri, 9am to 5pm PST 541-737-2272 [email protected]

Use of ASC Materials

Use & Attribution Info

Contact Info

- Categories: Engaging with Courses , Strategies for Learning

Reading is one of the most important components of college learning, and yet it’s one we often take for granted. Of course, students who come to Harvard know how to read, but many are unaware that there are different ways to read and that the strategies they use while reading can greatly impact memory and comprehension. Furthermore, students may find themselves encountering kinds of texts they haven’t worked with before, like academic articles and books, archival material, and theoretical texts.

So how should you approach reading in this new environment? And how do you manage the quantity of reading you’re asked to cover in college?

Start by asking “Why am I reading this?”

To read effectively, it helps to read with a goal . This means understanding before you begin reading what you need to get out of that reading. Having a goal is useful because it helps you focus on relevant information and know when you’re done reading, whether your eyes have seen every word or not.

Some sample reading goals:

- To find a paper topic or write a paper;

- To have a comment for discussion;

- To supplement ideas from lecture;

- To understand a particular concept;

- To memorize material for an exam;

- To research for an assignment;

- To enjoy the process (i.e., reading for pleasure!).

Your goals for reading are often developed in relation to your instructor’s goals in assigning the reading, but sometimes they will diverge. The point is to know what you want to get out of your reading and to make sure you’re approaching the text with that goal in mind. Write down your goal and use it to guide your reading process.

Next, ask yourself “How should I read this?”

Not every text you’re assigned in college should be read the same way. Depending on the type of reading you’re doing and your reading goal, you may find that different reading strategies are most supportive of your learning. Do you need to understand the main idea of your text? Or do you need to pay special attention to its language? Is there data you need to extract? Or are you reading to develop your own unique ideas?

The key is to choose a reading strategy that will help you achieve your reading goal. Factors to consider might be:

- The timing of your reading (e.g., before vs. after class)

- What type of text you are reading (e.g., an academic article vs. a novel)

- How dense or unfamiliar a text is

- How extensively you will be using the text

- What type of critical thinking (if any) you are expected to bring to the reading

Based on your consideration of these factors, you may decide to skim the text or focus your attention on a particular portion of it. You also might choose to find resources that can assist you in understanding the text if it is particularly dense or unfamiliar. For textbooks, you might even use a reading strategy like SQ3R .

Finally, ask yourself “How long will I give this reading?”

Often, we decide how long we will read a text by estimating our reading speed and calculating an appropriate length of time based on it. But this can lead to long stretches of engaging ineffectually with texts and losing sight of our reading goals. These calculations can also be quite inaccurate, since our reading speed is often determined by the density and familiarity of texts, which varies across assignments.

For each text you are reading, ask yourself “based on my reading goal, how long does this reading deserve ?” Sometimes, your answer will be “This is a super important reading. So, it takes as long as it takes.” In that case, create a time estimate using your best guess for your reading speed. Add some extra time to your estimate as a buffer in case your calculation is a little off. You won’t be sad to finish your reading early, but you’ll struggle if you haven’t given yourself enough time.

For other readings, once we ask how long the text deserves, we will realize based on our other academic commitments and a text’s importance in the course that we can only afford to give a certain amount of time to it. In that case, you want to create a time limit for your reading. Try to come up with a time limit that is appropriate for your reading goal. For instance, let’s say I am working with an academic article. I need to discuss it in class, but I can only afford to give it thirty minutes of time because we’re reading several articles for that class. In this case, I will set an alarm for thirty minutes and spend that time understanding the thesis/hypothesis and looking through the research to look for something I’d like to discuss in class. In this case, I might not read every word of the article, but I will spend my time focusing on the most important parts of the text based on how I need to use it.

If you need additional guidance or support, reach out to the course instructor and the ARC.

If you find yourself struggling through the readings for a course, you can ask the course instructor for guidance. Some ways to ask for help are: “How would you recommend I go about approaching the reading for this course?” or “Is there a way for me to check whether I am getting what I should be out of the readings?”

If you are looking for more tips on how to read effectively and efficiently, book an appointment with an academic coach at the ARC to discuss your specific assignments and how you can best approach them!

Seeing Textbooks in a New Light

Textbooks can be a fantastic supportive resource for your learning. They supplement the learning you’ll do in the classroom and can provide critical context for the material you cover there. In some courses, the textbook may even have been written by the professor to work in harmony with lectures.

There are a variety of ways in which professors use textbooks, so you need to assess critically how and when to read the textbook in each course you take.

Textbooks can provide:

- A fresh voice through which to absorb material. For challenging concepts, they can offer new language and details that might fill in gaps in your understanding.

- The chance to “preview” lecture material, priming your mind for the big ideas you’ll be exposed to in class.

- The chance to review material, making sense of the finer points after class.

- A resource that is accessible any time, whether it’s while you are studying for an exam, writing a paper, or completing a homework assignment.

Textbook reading is similar to and different from other kinds of reading . Some things to keep in mind as you experiment with its use:

The answer is “both” and “it depends.” In general, reading or at least previewing the assigned textbook material before lecture will help you pay attention in class and pull out the more important information from lecture, which also tends to make note-taking easier. If you read the textbook before class, then a quick review after lecture is useful for solidifying the information in memory, filling in details that you missed, and addressing gaps in your understanding. In addition, reading before and/or after class also depends on the material, your experience level with it, and the style of the text. It’s a good idea to experiment with when works best for you!

Just like other kinds of course reading, it is still important to read with a goal . Focus your reading goals on the particular section of the textbook that you are reading: Why is it important to the course I’m taking? What are the big takeaways? Also take note of any questions you may have that are still unresolved.

Reading linearly (left to right and top to bottom) does not always make the most sense. Try to gain a sense of the big ideas within the reading before you start: Survey for structure, ask Questions, and then Read – go back to flesh out the finer points within the most important and detail-rich sections.

Summarizing pushes you to identify the main points of the reading and articulate them succinctly in your own words, making it more likely that you will be able to retrieve this information later. To further strengthen your retrieval abilities, quiz yourself when you are done reading and summarizing. Quizzing yourself allows what you’ve read to enter your memory with more lasting potential, so you’ll be able to recall the information for exams or papers.

Marking Text

Marking text, which often involves making marginal notes, helps with reading comprehension by keeping you focused. It also helps you find important information when reviewing for an exam or preparing to write an essay. The next time you’re reading, write notes in the margins as you go or, if you prefer, make notes on a separate document.

Your marginal notes will vary depending on the type of reading. Some possible areas of focus:

- What themes do you see in the reading that relate to class discussions?

- What themes do you see in the reading that you have seen in other readings?

- What questions does the reading raise in your mind?

- What does the reading make you want to research more?

- Where do you see contradictions within the reading or in relation to other readings for the course?

- Can you connect themes or events to your own experiences?

Your notes don’t have to be long. You can just write two or three words to jog your memory. For example, if you notice that a book has a theme relating to friendship, you can just write, “pp. 52-53 Theme: Friendship.” If you need to remind yourself of the details later in the semester, you can re-read that part of the text more closely.

Reading Workshops

If you are looking for help with developing best practices and using strategies for some of the tips listed above, come to an ARC workshop on reading!

Study Skills and Classroom Success

Reading strategies.

To read without reflecting is like eating without digesting. —Edmund Burke, author and philosopher

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Identify common types of reading tasks assigned in a college class

- Describe the purpose and instructor expectations of academic reading

- Identify effective reading strategies for academic texts: previewing, reading, summarizing, reviewing

- Explore strategies for approaching specialized texts, such as math, and specialized platforms, such as online text

- Identify vocabulary-building techniques to strengthen your reading comprehension

Types of College Reading Materials

As a college student, you will eventually choose a major or focus of study. In your first year or so, though, you’ll probably have to complete “core” or required classes in different subjects. For example, even if you plan to major in English, you may still have to take at least one science, history, and math class. These different academic disciplines (and the instructors who teach them) can vary greatly in terms of the materials that students are assigned to read. Not all college reading is the same. So, what types can you expect to encounter?

Probably the most familiar reading material in college is the textbook . These are academic books, usually focused on one discipline, and their primary purpose is to educate readers on a particular subject—”Principles of Algebra,” for example, or “Introduction to Business.” It’s not uncommon for instructors to use one textbook as the primary text for an entire course. Instructors typically assign chapters as readings and may include any word problems or questions in the textbook, too.

Instructors may also assign academic articles or news articles . Academic articles are written by people who specialize in a particular field or subject, while news articles may be from recent newspapers and magazines. For example, in a science class, you may be asked to read an academic article on the benefits of rainforest preservation, whereas in a government class, you may be asked to read an article summarizing a recent presidential debate. Instructors may have you read the articles online or they may distribute copies in class or electronically.

The chief difference between news and academic articles is the intended audience of the publication. News articles are mass media: They are written for a broad audience, and they are published in magazines and newspapers that are generally available for purchase at grocery stores or bookstores. They may also be available online. Academic articles, on the other hand, are usually published in scholarly journals with fairly small circulations. While you won’t be able to purchase individual journal issues from Barnes and Noble, public and school libraries do make these journal issues and individual articles available. It’s common to access academic articles through online databases hosted by libraries.

Literature and Nonfiction Books

Instructors use literature and nonfiction books in their classes to teach students about different genres, events, time periods, and perspectives. For example, a history instructor might ask you to read the diary of a girl who lived during the Great Depression so you can learn what life was like back then. In an English class, your instructor might assign a series of short stories written during the 1960s by different American authors, so you can compare styles and thematic concerns.

Literature includes short stories, novels or novellas, graphic novels, drama, and poetry. Nonfiction works include creative nonfiction—narrative stories told from real life—as well as history, biography, and reference materials. Textbooks and scholarly articles are specific types of nonfiction; often their purpose is to instruct, whereas other forms of nonfiction be written to inform, to persuade, or to entertain.

Purpose of Academic Reading

Casual reading across genres, from books and magazines to newspapers and blogs, is something students should be encouraged to do in their free time because it can be both educational and fun. In college, however, instructors generally expect students to read resources that have particular value in the context of a course. Why is academic reading beneficial?

- Information comes from reputable sources : Web sites and blogs can be a source of insight and information, but not all are useful as academic resources. They may be written by people or companies whose main purpose is to share an opinion or sell you something. Academic sources such as textbooks and scholarly journal articles, on the other hand, are usually written by experts in the field and have to pass stringent peer review requirements in order to get published.

- Learn how to form arguments : In most college classes except for creating writing, when instructors ask you to write a paper, they expect it to be argumentative in style. This means that the goal of the paper is to research a topic and develop an argument about it using evidence and facts to support your position. Since many college reading assignments (especially journal articles) are written in a similar style, you’ll gain experience studying their strategies and learning to emulate them.

- Exposure to different viewpoints : One purpose of assigned academic readings is to give students exposure to different viewpoints and ideas. For example, in an ethics class, you might be asked to read a series of articles written by medical professionals and religious leaders who are pro-life or pro-choice and consider the validity of their arguments. Such experience can help you wrestle with ideas and beliefs in new ways and develop a better understanding of how others’ views differ from your own.

Activity: Describing the Purpose of Academic Reading

- Describe the purpose of academic reading and what an instructor might expect of you after reading

- Review the main types of academic reading and the purpose of academic reading.

- Imagine you are an instructor for a class. This could be a class you are currently taking or one you would like to see offered.

- Identify three academic readings that you would assign to your students.

- Explain why you would assign these works and what you would expect your students to learn or do after reading them.

- Follow your instructor’s guidelines for submitting assignments.

Reading Strategies for Academic Texts

Recall from the Active Learning section that effective reading requires more engagement than just reading the words on the page. In order to learn and retain what you read, it’s a good idea to do things like circling key words, writing notes, and reflecting. Actively reading academic texts can be challenging for students who are used to reading for entertainment alone, but practicing the following steps will get you up to speed:

- Preview : You can gain insight from an academic text before you even begin the reading assignment. For example, if you are assigned a nonfiction book, read the title, the back of the book, and table of contents. Scanning this information can give you an initial idea of what you’ll be reading and some useful context for thinking about it. You can also start to make connections between the new reading and knowledge you already have, which is another strategy for retaining information.

- Read : While you read an academic text, you should have a pen or pencil in hand. Circle or highlight key concepts. Write questions or comments in the margins or in a notebook. This will help you remember what you are reading and also build a personal connection with the subject matter.

- Summarize : After you an read academic text, it’s worth taking the time to write a short summary—even if your instructor doesn’t require it. The exercise of jotting down a few sentences or a short paragraph capturing the main ideas of the reading is enormously beneficial: it not only helps you understand and absorb what you read but gives you ready study and review materials for exams and other writing assignments.

- Review : It always helps to revisit what you’ve read for a quick refresher. It may not be practical to thoroughly reread assignments from start to finish, but before class discussions or tests, it’s a good idea to skim through them to identify the main points, reread any notes at the ends of chapters, and review any summaries you’ve written.

The following video covers additional active reading strategies readers can use before, during, and after the reading process.

Reading Strategies for Specialized Texts and Online Resources

In college it’s not uncommon to experience frustration with reading assignments from time to time. Because you’re doing more reading on your own outside the classroom, and with less frequent contact with instructors than you had in high school, it’s possible you’ll encounter readings that contain unfamiliar vocabulary or don’t readily make sense. Different disciplines and subjects have different writing conventions and styles, and it can take some practice to get to know them. For example, scientific articles follow a very particular format and typically contain the following sections: an abstract, introduction, methods, results, and discussions. If you are used to reading literary works, such as graphic novels or poetry, it can be disorienting to encounter these new forms of writing.

Below are some strategies for making different kinds of texts more approachable.

Get to Know the Conventions

Academic texts, like scientific studies and journal articles, may have sections that are new to you. If you’re not sure what an “abstract” is, research it online or ask your instructor. Understanding the meaning and purpose of such conventions is not only helpful for reading comprehension but for writing, too.

Look up and Keep Track of Unfamiliar Terms and Phrases

Have a good college dictionary such as Merriam-Webster handy (or find it online) when you read complex academic texts, so you can look up the meaning of unfamiliar words and terms. Many textbooks also contain glossaries or “key terms” sections at the ends of chapters or the end of the book. If you can’t find the words you’re looking for in a standard dictionary, you may need one specially written for a particular discipline. For example, a medical dictionary would be a good resource for a course in anatomy and physiology.

If you circle or underline terms and phrases that appear repeatedly, you’ll have a visual reminder to review and learn them. Repetition helps to lock in these new words and their meaning get them into long-term memory, so the more you review them the more you’ll understand and feel comfortable using them.

Look for Main Ideas and Themes

As a college student, you are not expected to understand every single word or idea presented in a reading, especially if you haven’t discussed it in class yet. However, you will get more out of discussions and feel more confident about asking questions if you can identify the main idea or thesis in a reading. The thesis statement can often (but not always) be found in the introductory paragraph, and it may be introduced with a phrase like “In this essay I argue that . . .” Getting a handle on the overall reason an author wrote something (“to prove X” or “to explore Y,” for instance) gives you a framework for understanding more of the details. It’s also useful to keep track of any themes you notice in the writing. A theme may be a recurring idea, word, or image that strikes you as interesting or important: “This story is about men working in a gloomy factory, but the author keeps mentioning birds and bats and windows. Why is that??”

Get the Most of Online Reading

Reading online texts presents unique challenges for some students. For one thing, you can’t readily circle or underline key terms or passages on the screen with a pencil. For another, there can be many tempting distractions—just a quick visit to amazon.com or Facebook.

While there’s no substitute for old-fashioned self-discipline, you can take advantage of the following tips to make online reading more efficient and effective:

- Where possible, download the reading as a PDF, Word document, etc., so you can read it offline.

- Get one of the apps that allow you to disable your social media sites for specified periods of time.

- Adjust your screen to avoid glare and eye strain, and change the text font to be less distracting (for those essays written in Comic Sans).

- Install an annotation tool in your Web browser so you can highlight and make notes on online text. One to try is hypothes.is . A low-tech option is to have a notebook handy to write in as you read.

Look for Reputable Online Sources

Professors tend to assign reading from reputable print and online sources, so you can feel comfortable referencing such sources in class and for writing assignments. If you are looking for online sources independently, however, devote some time and energy to critically evaluating the quality of the source before spending time reading any resources you find there. Find out what you can about the author (if one is listed), the Web site, and any affiliated sponsors it may have. Check that the information is current and accurate against similar information on other pages. Depending on what you are researching, sites that end in “.edu” (indicating an “education” site such as a college, university, or other academic institution) tend to be more reliable than “.com” sites.

Pay Attention to Visual Information

Images in textbooks or journals usually contain valuable information to help you more deeply grasp a topic. Graphs and charts, for instance, help show the relationship between different kinds of information or data—how a population changes over time, how a virus spreads through a population, etc.

Data-rich graphics can take longer to “read” than the text around them because they present a lot of information in a condensed form. Give yourself plenty of time to study these items, as they often provide new and lasting insights that are easy to recall later (like in the middle of an exam on that topic!).

Vocabulary-Building Techniques

Gaining confidence with unique terminology used in different disciplines can help you be more successful in your courses and in college generally. In addition to the suggestions described earlier, such as looking up unfamiliar words in dictionaries, the following are additional vocabulary-building techniques for you to try:

Read Everything and Read Often

Reading frequently both in and out of the classroom will help strengthen your vocabulary. Whenever you read a book, magazine, newspaper, blog, or any other resource, keep a running list of words you don’t know. Look up the words as you encounter them and try to incorporate them into your own speaking and writing.

Make Connections to Words You Already Know

You may be familiar with the “looks like . . . sounds like” saying that applies to words. It means that you can sometimes look at a new word and guess the definition based on similar words whose meaning you know. For example, if you are reading a biology book on the human body and come across the word malignant , you might guess that this word means something negative or broken if you already know the word malfunction, which share the “mal-” prefix.

Make Index Cards

If you are studying certain words for a test, or you know that certain phrases will be used frequently in a course or field, try making flashcards for review. For each key term, write the word on one side of an index card and the definition on the other. Drill yourself, and then ask your friends to help quiz you.

Developing a strong vocabulary is similar to most hobbies and activities. Even experts in a field continue to encounter and adopt new words. The following video discusses more strategies for improving vocabulary.

Words are sneaky, charming, and intriguing. The more complex our vocabularies, the more complex our thoughts are, too.

- Reading Strategies. Authored by : Jolene Carr. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

- Reading on a Rock. Authored by : Spanginator. Located at : https://www.flickr.com/photos/spanginator/3414054443/sizes/l . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- College Reading Strategies. Authored by : The Learning Center at the University of Hawaii Maui College. Located at : https://youtu.be/faZF9x4A2Vs . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Image of man reading under tree. Authored by : Ken Slade. Located at : https://flic.kr/p/auziyg . License : CC BY-NC: Attribution-NonCommercial

- Vocabulary Reading Strategies. Authored by : Lindsey Thompson. Located at : https://youtu.be/nfbY0EK7JEY . License : CC BY: Attribution

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

5.2 How Do You Read to Learn?

Learning objectives.

- Understand the four steps of active learning.

- Develop strategies to help you read effectively and quickly.

The four steps of active reading are almost identical to the four phases of the learning cycle—and that is no coincidence! Active reading is learning through reading the written word, so the learning cycle naturally applies. Active reading involves these steps:

- Capturing the key ideas

Let’s take a look at how to use each step when reading.

Preparing to Read

Start by thinking about why your instructor has chosen this text. Has the instructor said anything about the book or the author? Look at the table of contents; how does it compare with the course syllabus? What can you learn about the author from the front matter of the book (see Table 5.1 “Anatomy of a Textbook” )? Understanding this background will give you the context of the book and help define what is most important in the text. Doing this exercise once per textbook will give you a great deal of insight throughout the course.

Now it is time to develop a plan of attack for your assignment. Your first step in any reading assignment is to understand the context of what you are about to read. Think of your reading assignment in relation to the large themes or goals the instructor has spelled out for the class. Remember that you are not merely reading—you are reading for a purpose. What parts of a reading assignment should you pay special attention to, and what parts can you browse through? As we mentioned in the beginning of this chapter, you will be expected to do a considerable amount of reading in college, and you will not get through it all by reading each and every word with a high level of focus and mental intensity. This is why it is so important to learn to define where to invest your efforts.

Open your text to the assigned pages. What is the chapter title? Is the chapter divided into sections? What are the section titles? Which sections are longer? Are there any illustrations? What are they about? Illustrations in books cost money, so chances are the author and publisher thought these topics were particularly important, or they would not have been included. How about tables? What kinds of information do they show? Are there bold or italicized words? Are these terms you are familiar with, or are they new to you? Are you getting a sense for what is important in the chapter? Use the critical thinking skills discussed in Chapter 3 “Thinking about Thought” as you think about your observations. Why did the author choose to cover certain ideas and to highlight specific ideas with graphics or boldface fonts? What do they tell you about what will be most important for you in your course? What do you think your instructor wants you to get out of the assignment? Why?

Anatomy of a Textbook

Good textbooks are designed to help you learn, not just to present information. They differ from other types of academic publications intended to present research findings, advance new ideas, or deeply examine a specific subject. Textbooks have many features worth exploring because they can help you understand your reading better and learn more effectively. In your textbooks, look for the elements listed in the table below.

Table 5.1 Anatomy of a Textbook

| Textbook Feature | What It Is | Why You Might Find It Helpful |

|---|---|---|

| Preface or Introduction | A section at the beginning of a book in which the author or editor outlines its purpose and scope, acknowledges individuals who helped prepare the book, and perhaps outlines the features of the book. | You will gain perspective on the author’s point of view, what the author considers important. If the preface is written with the student in mind, it will also give you guidance on how to “use” the textbook and its features. |

| Foreword | A section at the beginning of the book, often written by an expert in the subject matter (different from the author) endorsing the author’s work and explaining why the work is significant. | A foreword will give you an idea about what makes this book different from others in the field. It may provide hints as to why your instructor selected the book for your course. |

| Author Profile | A short biography of the author illustrating the author’s credibility in the subject matter. | This will help you understand the author’s perspective and what the author considers important. |

| Table of Contents | A listing of all the chapters in the book and, in most cases, primary sections within chapters. | The table of contents is an outline of the entire book. It will be very helpful in establishing links among the text, the course objectives, and the syllabus. |

| Chapter Preview or Learning Objectives | A section at the beginning of each chapter in which the author outlines what will be covered in the chapter and what the student should expect to know or be able to do at the end of the chapter. | These sections are invaluable for determining what you should pay special attention to. Be sure to compare these outcomes with the objectives stated in the course syllabus. |

| Introduction | The first paragraph(s) of a chapter, which states the chapter’s objectives and key themes. An introduction is also common at the beginning of primary chapter sections. | Introductions to chapters or sections are “must reads” because they give you a road map to the material you are about to read, pointing you to what is truly important in the chapter or section. |

| Applied Practice Elements | Exercises, activities, or drills designed to let students apply their knowledge gained from the reading. Some of these features may be presented via Web sites designed to supplement the text. | These features provide you with a great way to confirm your understanding of the material. If you have trouble with them, you should go back and reread the section. They also have the additional benefit of improving your recall of the material. |

| Chapter Summary | A section at the end of a chapter that confirms key ideas presented in the chapter. | It is a good idea to read this section before you read the body of the chapter. It will help you strategize about where you should invest your reading effort. |

| Review Material | A section at the end of the chapter that includes additional applied practice exercises, review questions, and suggestions for further reading. | The review questions will help you confirm your understanding of the material. |

| Endnotes and Bibliographies | Formal citations of sources used to prepare the text. | These will help you infer the author’s biases and are also valuable if doing further research on the subject for a paper. |

Now, before actually starting to read, try to give your reading more direction. Are you ever bored when reading a textbook? Students sometimes feel that about some of their textbooks. In this step, you create a purpose or quest for your reading, and this will help you become more actively engaged and less bored.

Start by checking your attitude: if you are unhappy about the reading assignment and complaining that you even have to read it, you will have trouble with the reading. You need to get “psyched” for the assignment. Stoke your determination by setting yourself a reasonable time to complete the assignment and schedule some short breaks for yourself. Approach the reading with a sense of curiosity and thirst for new understanding. Think of yourself more as an investigator looking for answers than a student doing a homework assignment.

Take out your notebook for the class for which you are doing the reading. Remember the Cornell method of note taking from Chapter 4 “Listening, Taking Notes, and Remembering” ? You will use the same format here with a narrow column on the left and a wide column on the right. This time, with reading, approach taking notes slightly differently. In the Cornell method used for class notes, you took notes in the right column and wrote in questions and comments in the left column after class as you reviewed your notes. When using this system with reading, write your questions about the reading first in the left column (spacing them well apart so that you have plenty of room for your notes while you read in the right column). From your preliminary scanning of the pages, as described previously, you should already have questions at your fingertips.

Use your critical thinking skill of questioning what the author is saying. Turn the title of each major section of the reading into a question and write it down in your left column of your notes. For example, if the section title is “The End of the Industrial Revolution,” you might write, “What caused the Industrial Revolution to end?” If the section title is “The Chemistry of Photosynthesis,” you might write, “What chemical reactions take place to cause photosynthesis, and what are the outcomes?” Note that your questions are related to the kind of material you are hearing about in class, and they usually require not a short answer but a thoughtful, complete understanding. Ideally, you should not already know the answer to the questions you are writing! (What fun is a quest if you already know each turn and strategy? Expect to learn something new in your reading even if you are familiar with the topic already.) Finally, also in the left column, jot down any keywords that appear in boldface. You will want to discover their definitions and the significance of each as you read.

Activity: Try It Now!

OK. Time to take a break from reading this book. Choose a textbook in which you have a current reading assignment. Scan the assigned pages, looking for what is really important, and write down your questions using the Cornell method.

Now answer the following questions with a journal entry.

- Do you feel better prepared to read this assignment? How?

- Do you feel more confident?

- Do you feel less overwhelmed?

- Do you feel more focused?

________________________________________________________________________________

Alternative Approaches for Preparing to Read

In Chapter 4 “Listening, Taking Notes, and Remembering” you may have determined that you are more comfortable with the outline or concept map methods of note taking. You can use either of these methods also to prepare for reading. With the outline method, start with the chapter title as your primary heading, then create subheadings for each section, rephrasing each section title in terms of a question.

If you are more comfortable using the concept map method, start with the chapter title as your center and create branches for each section within the chapter. Make sure you phrase each item as a question.

Now you are ready to start reading actively. Start by taking a look at your notes; they are your road map. What is the question you would like to answer in the first section? Before you start reading, reflect about what you already know about the subject. Even if you don’t know anything, this step helps put you in the right mind-set to accept new material. Now read through the entire section with the objective of understanding it. Follow these tips while reading, but do not start taking notes or highlighting text at this point:

- Look for answers to the questions you wrote.

- Pay particular attention to the first and last lines of each paragraph.

- Think about the relationships among section titles, boldface words, and graphics.

- Skim quickly over parts of the section that are not related to the key questions.

After reading the section, can you answer the section question you earlier wrote in your notes? Did you discover additional questions that you should have asked or that were not evident from the title of the section? Write them down now on your notes page. Can you define the keywords used in the text? If you can’t do either of these things, go back and reread the section.

Capture the Key Ideas

Once you can answer your questions effectively and can define the new and keywords, it is time to commit these concepts to your notes and to your memory. Start by writing the answers to your questions in your notes in the right column. Also define the keywords you found in the reading.

Now is also the time to go back and reread the section with your highlighter or pencil to call out key ideas and words and make notes in your margins. Marking up your book may go against what you were told in high school, when the school owned the books and expected to use them year after year. In college, you bought the book. Make it truly yours. Although some students may tell you that you can get more cash by selling a used book that is not marked up, this should not be a concern at this time—that’s not nearly as important as understanding the reading and doing well in the class!

The purpose of marking your textbook is to make it your personal studying assistant with the key ideas called out in the text. Most readers tend to highlight too much, however, hiding key ideas in a sea of yellow lines. When it comes to highlighting, less is more. Think critically before you highlight. Your choices will have a big impact on what you study and learn for the course. Make it your objective to highlight no more than 10 percent of the text.

Use your pencil also to make annotations in the margin. Use a symbol like an exclamation mark ( ! ) or an asterisk ( * ) to mark an idea that is particularly important. Use a question mark ( ? ) to indicate something you don’t understand or are unclear about. Box new words, then write a short definition in the margin. Use “TQ” (for “test question”) or some other shorthand or symbol to signal key things that may appear in test or quiz questions. Write personal notes on items where you disagree with the author. Don’t feel you have to use the symbols listed here; create your own if you want, but be consistent. Your notes won’t help you if the first question you later have is “I wonder what I meant by that?”

If you are reading an essay from a magazine or an academic journal, remember that such articles are typically written in response to other articles. In Chapter 4 “Listening, Taking Notes, and Remembering” , you learned to be on the lookout for signal words when you listen. This applies to reading, too. You’ll need to be especially alert to signals like “according to” or “Jones argues,” which make it clear that the ideas don’t belong to the author of the piece you are reading. Be sure to note when an author is quoting someone else or summarizing another person’s position. Sometimes, students in a hurry to get through a complicated article don’t clearly distinguish the author’s ideas from the ideas the author argues against. Other words like “yet” or “however” indicate a turn from one idea to another. Words like “critical,” “significant,” and “important” signal ideas you should look at closely.

After annotating, you are ready to read the next section.

Reviewing What You Read

When you have completed each of the sections for your assignment, you should review what you have read. Start by answering these questions: “What did I learn?” and “What does it mean?” Next, write a summary of your assigned reading, in your own words, in the box at the base of your notepaper. Working from your notes, cover up the answers to your questions and answer each of your questions aloud. (Yes, out loud. Remember from Chapter 4 “Listening, Taking Notes, and Remembering” that memory is improved by using as many senses as possible?) Think about how each idea relates to material the instructor is covering in class. Think about how this new knowledge may be applied in your next class.

If the text has review questions at the end of the chapter, answer those, too. Talk to other students about the reading assignment. Merge your reading notes with your class notes and review both together. How does your reading increase your understanding of what you have covered in class and vice versa?

Strategies for Textbook Reading

The four steps to active reading provide a proven approach to effective learning from texts. Following are some strategies you can use to enhance your reading even further:

- Pace yourself. Figure out how much time you have to complete the assignment. Divide the assignment into smaller blocks rather than trying to read the entire assignment in one sitting. If you have a week to do the assignment, for example, divide the work into five daily blocks, not seven; that way you won’t be behind if something comes up to prevent you from doing your work on a given day. If everything works out on schedule, you’ll end up with an extra day for review.

- Schedule your reading. Set aside blocks of time, preferably at the time of the day when you are most alert, to do your reading assignments. Don’t just leave them for the end of the day after completing written and other assignments.

- Get yourself in the right space. Choose to read in a quiet, well-lit space. Your chair should be comfortable but provide good support. Libraries were designed for reading—they should be your first option! Don’t use your bed for reading textbooks; since the time you were read bedtime stories, you have probably associated reading in bed with preparation for sleeping. The combination of the cozy bed, comforting memories, and dry text is sure to invite some shut-eye!

- Avoid distractions. Active reading takes place in your short-term memory. Every time you move from task to task, you have to “reboot” your short-term memory and you lose the continuity of active reading. Multitasking—listening to music or texting on your cell while you read—will cause you to lose your place and force you to start over again. Every time you lose focus, you cut your effectiveness and increase the amount of time you need to complete the assignment.

- Avoid reading fatigue. Work for about fifty minutes, and then give yourself a break for five to ten minutes. Put down the book, walk around, get a snack, stretch, or do some deep knee bends. Short physical activity will do wonders to help you feel refreshed.

- Read your most difficult assignments early in your reading time, when you are freshest.

- Make your reading interesting. Try connecting the material you are reading with your class lectures or with other chapters. Ask yourself where you disagree with the author. Approach finding answers to your questions like an investigative reporter. Carry on a mental conversation with the author.

Key Takeaways

- Consider why the instructor has selected the particular text. Map the table of contents to the course syllabus.

- Understand how your textbook is put together and what features might help you with your reading.

- Plan your reading by scanning the reading assignment first, then create questions based on the section titles. These will help you focus and prioritize your reading.

- Use the Cornell method for planning your reading and recording key ideas.

- Don’t try to highlight your text as you read the first time through. At that point, it is hard to tell what is really important.

- End your reading time by reviewing your notes.

- Pace yourself and read in a quiet space with minimal distractions.

Checkpoint Exercises

List the four steps to active reading. Which one do you think will take most time? Why?

__________________________________________________________________

Think of your most difficult textbook. What features can you use to help you understand the material better?

What things most commonly distract you when you are reading? What can you do to control these distractions?

List three specific places on your campus or at home that are appropriate for you to do your reading assignments. Which is best suited? What can you do to improve that reading environment?

College Success Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Study Skills Support

University of Sunderland

Reading for Assignment Success: Note taking and reading

Note taking and reading

You might take notes when listening to a lecture, watching a video or when reading. Taking notes can be a good way to remind yourself of important points but it is not just copying down what you hear or read and then using them in your assignments.

Good note taking will require you to engage actively with your texts. A good note taking strategy can help you use the critical thinking methods discussed in earlier sections.

Go to the following hyperlink and read the article. Make notes in whatever way you usually would. If you do not have any paper you could open up the notepad on your computer.

More than half of children in England and Wales bullied about appearance [Opens in a new window or browser tab]

In the last activity you made notes on a newspaper article. You may have found that in your notes you copied the key points of what you read, but did you apply critical thinking to your notes?

Having a good note taking method can help you understand what you read, think critically about it and then incorporate the ideas into your assignments. Here we will outline a strategy for note taking that you can use when reading or listening to lectures.

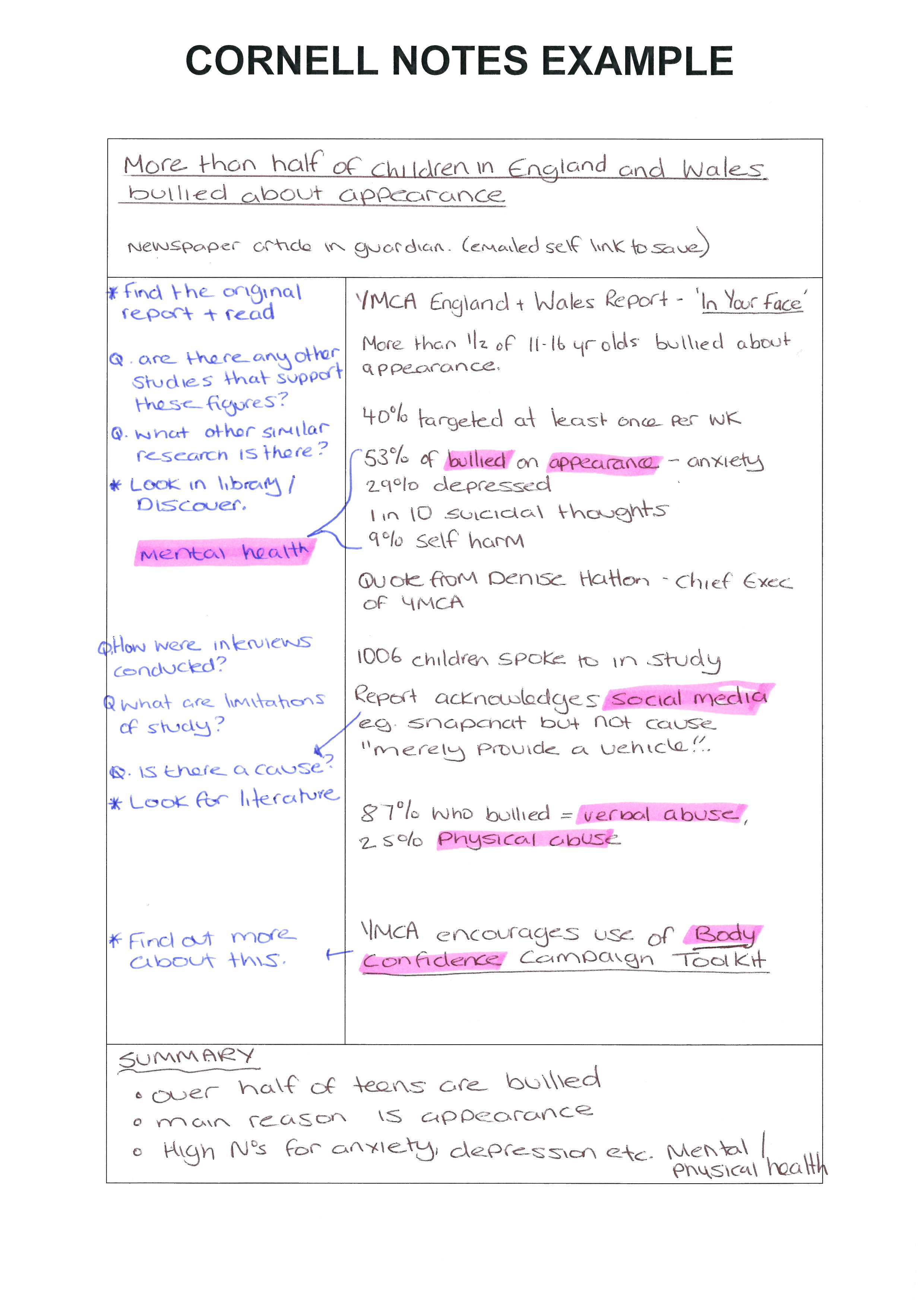

The Cornell Notes Method

The Cornell Notes method is a great way to engage with your reading. It’s also useful for taking lecture notes too. When you use this method you will divide your note paper into three sections, one for the key points. One to ask questions, write definitions, and identify actions and one to write a summary.

Watch the video ‘ How To: Take Cornell Notes ‘ to learn about the Cornell Method and how one student uses it to better understand her topic.

Here is an example of some notes on The Guardian article linked in the last activity. Note that the key points are identified in the right column, some questions about these points have been written along with some actions and a summary has been added in the bottom section.

In an extra step some keywords have been highlighted which could be used when doing a search for more research on this topic.

Whether you choose to use this method or your own the key thing to keep in mind is to engage with your reading by asking questions and to review your notes several times afterwards.

Answer the multiple choice question below.

University of Sunderland links

- Library Web Page

- Study Skills

- Contact the Library

- Off Campus Library Support

Navigate this tutorial

- 1. Why students need to read

- 2. How to read like a student

- 3. Questioning your reading

- 4. Note taking and reading

- 5. What do students need to read?

- 6. Where to find your reading

- 7. An intro to academic journals

- 8. Help and support in your studies

- 9. Tips for managing your reading

- WRITING SKILLS

Note-Taking from Reading

Search SkillsYouNeed:

Writing Skills:

- A - Z List of Writing Skills

The Essentials of Writing

- Common Mistakes in Writing

- Introduction to Grammar

- Improving Your Grammar

- Active and Passive Voice

- Punctuation

- Clarity in Writing

- Writing Concisely

- Coherence in Writing

- Gender Neutral Language

- Figurative Language

- When to Use Capital Letters

- Using Plain English

- Writing in UK and US English

- Understanding (and Avoiding) Clichés

- The Importance of Structure

- Know Your Audience

- Know Your Medium

- Formal and Informal Writing Styles

- Note-Taking for Verbal Exchanges

- Creative Writing

- Top Tips for Writing Fiction

- Writer's Voice

- Writing for Children

- Writing for Pleasure

- Writing for the Internet

- Journalistic Writing

- Technical Writing

- Academic Writing

- Editing and Proofreading

Writing Specific Documents

- Writing a CV or Résumé

- Writing a Covering Letter

- Writing a Personal Statement

- Writing Reviews

- Using LinkedIn Effectively

- Business Writing

- Study Skills

- Writing Your Dissertation or Thesis

Subscribe to our FREE newsletter and start improving your life in just 5 minutes a day.

You'll get our 5 free 'One Minute Life Skills' and our weekly newsletter.

We'll never share your email address and you can unsubscribe at any time.

When engaged in some form of study or research, either informally or formally, you will probably need to read and take in a lot of information.

This page describes how to take effective notes while reading. Taking notes is a way to engage with the printed word, and can help you to retain more of the information, especially if you summarise and paraphrase it.

There are plenty of ways to take notes, both in terms of the tools you use (pen and paper or computer, for example), and the style of notes. Some of these may be more effective, and some may be a matter of choice and personal preference.

This page covers some of the principles involved to help you make the most appropriate choice for you.

Further reading from SkillsYouNeed

We have a series of other related pages that you may find helpful. Our page, Effective Note-Taking covers how to take notes when you are listening to the information, rather than reading it. It is therefore useful for classes, lectures, and meetings.

See our pages: Effective Reading and Critical Reading for explanation, advice and comment on how to get the most from, and develop your, reading.

Why Take Notes When Reading?

Reading for pleasure or as a way to relax, such as reading a novel, newspaper or magazine, is usually a ‘passive’ exercise. When you are studying, reading should be seen as an ‘active’ exercise.

In other words, you engage with your reading to maximise your learning.

One of the most effective ways of actively engaging with your reading is to make notes as you go along.

However, how much you take in seems to depend on how you take notes. Research shows that students who took notes by hand, using pen and paper, tended to retain significantly more information than those who used computers. It was suggested that this was because those writing by hand tended to summarise the points more, whereas those with computers tended to type verbatim and therefore engage less with the content.

Paraphrasing and summarising what you read in your own words is far more effective in helping you to retain information. This seems likely to apply whether you are using a computer or a pen and paper.

By writing notes, in your own words, you will be forced to think about the ideas that are presented in the text and how you can explain them coherently. The process of note-taking will, therefore, help you retain, analyse and ultimately remember and learn what you have read.

What NOT To Do

It is important to understand that effective note-taking requires you to write notes on what you have read in your own words.

Copying what others have said is not note-taking and is only appropriate when you want to directly quote an author. It can be tempting, especially if your reading material is online, to copy and paste straight into a document. If you do this, then you are unlikely to learn or reflect on what you have read, as copying is not engaging with the text.

Copying, Referencing and Plagiarism

As a general principle, you should expect to summarise and paraphrase other authors’ ideas rather than quote them verbatim. This helps to show that you have understood the ideas and are able to set them into context. When you summarise an author’s ideas, you need to provide a citation to the original source.

It is, however, acceptable to quote another author if they make a point particularly neatly , but you should do so sparingly. If you quote directly, your citation usually needs to include the page number.

Copying and/or discussing someone else’s ideas without proper attribution is plagiarism.

This is a serious academic offence. See our page: Academic Referencing for more information and instructions on how to reference properly.

Use online sources as appropriate but summarise, re-write and/or paraphrase and always reference.

Effective Steps for Note-Taking

There is no magic formula to taking notes when reading. You simply have to find out what works best for you. Your note-taking skills will develop with practice and as you realise the benefits. This section is designed to help you get started.

1. Highlighting and Emphasising

A quick and easy way to be active when reading is to highlight and/or underline parts of the text. Although the process of highlighting is not ‘note-taking’, it is often an important first step. Many people also recommend making brief notes in the margin. Of course, this is not a good idea if the book or journal does not belong to you! In such cases, make notes on a photocopy or use sticky ‘post it’ notes or similar.

Highlighting key words or phrases in text will help you:

- Focus your attention on what you are reading – and make it easy to see key points when re-reading.

- Think more carefully about the key concepts and ideas in the text, the bits that are worth highlighting.

- See immediately whether you have already read pages or sections of text.

When you come across words or phrases that you are not familiar with it may be useful to add them to a personal glossary of terms . Make a glossary on a separate sheet (or document) of notes, so you can easily refer and update it as necessary. Write descriptions of the terms in your own words to further encourage learning.

2. Making Written Notes

Although highlighting is a quick way of emphasising key points, it is no substitute for taking proper notes.

Remember your main purpose in taking notes is to learn, and probably to prepare for some form of writing. When you first start to take notes, you may find that you take too many, or not enough, or that when you revisit them they are unclear, or you do not know which is your opinion and which is the opinion of the author. You will need to work on these areas - like all life skills, taking effective notes improves with practice.

There are two main elements that you need to include in your notes:

- The content of your reading , usually through brief summaries or paraphrasing, plus a few well-chosen quotes (with page numbers); and

- Your reaction to the content , which may include an emotional reaction and also questions that you feel it raises.

It can be helpful to separate these two physically to ensure that you include both (see box).

Your notes may also take various forms and style, for example:

- Linear , or moving from one section to the next on the page in a logical way, using headings and sub-headings;

- Diagrammatic , using boxes and flowcharts to help you move around the page; and

- Patterns, such as mind maps, which allow a large amount of information to be included in a single page, but rely on you to remember the underlying information.

The style that you use is very personal: some people prefer a more linear approach, and others like the visual elements of mind-mapping or diagrams. It is worth trying a number of approaches to see which one(s) work best for you, and under which circumstances.

TOP TIP! A Suggested Format for Notes

One useful way to make notes that encourages you to include both content and reaction is to separate your page into two.

- Use the left-hand side to summarise and paraphrase the content. When you first start taking notes, it is worth including a reasonable level of detail (say, one sentence per paragraph), although as you become more experienced you will get a better feel for when this is not necessary. You should also record a few interesting quotes (in quotation marks, and with details of the page number).

- Use the right-hand side to comment on your reaction, including whether you agree or disagree with the author. It is worth adding details of any personal memories that are ‘jogged’ by the content, as this will help you to remember it better.

As you complete each page of notes, check to make sure that both columns are reasonably full.

Remember to include the source of each point, including the page and/or paragraph number, to make it easier to refer back if necessary.

- When referring to a book, record the author's name, the date of publication, the title of the book, the relevant page number, the name of the publisher and the place of publication.

- When referring to a magazine or newspaper, record the name of the author of the article, the date of publication, the name of the article, the name of the publication, the publication number and page number.

- When referring to internet sources, record (at least) the full URL or web address and the date you accessed the information.

See our page: Academic Referencing for more detailed information on how to reference correctly.

As well as notes on the detailed content, it is also worth compiling a summary at the end of each section or chapter.

A summary is, by definition, precise. Its aim is to bring together the essential points and to simplify the main argument or viewpoint of the author. You should be able to use your summary in the future to refer to the points raised and use your own explanations and examples of how they may apply to your subject area.

3. Reviewing and Revising Your Notes

Once you have gone through the text and made notes as you go, you will have a reasonable summary of the document, and your reactions to it.

However, as you read the whole document, other things may emerge. For example, as you reflect on your reading, you may notice themes emerging, or you may find that your earlier reactions have softened or sharpened as you have gone through, particularly for books.

It is therefore helpful to review your notes a few days after completing them. In particular, you may want to:

- Use headings or different sheets (or documents) to separate different themes and ideas;

- Use brightly coloured pens or flags to highlight important points in your notes. You may find it useful to have a simple system of colour-coding, using different colours for particular themes or issues; and

- Note where your opinions changed, and why.

4. Organising Your Notes

Depending on your circumstances, you may find you accumulate a lot of notes.

Notes are of no use to you if you cannot find them when you need to, and spending a lot of time sifting through piles of papers is a waste of time. It is therefore important to ensure that your notes are well-organised and you can find what you want when you need it.

How you organise your notes will depend on whether they are ‘physical’, written on paper or ‘digital’, stored on a computer, or a combination of the two. It will also depend on your personal preferences, but good options include binders and folders, whether real or digital. There are also a number of apps that can help you to store and recover information effectively.

Finding Your Way

Ultimately, how you write and organise your notes is up to you. It is a very personal choice, and you may also find that you have different preferences for reading for assignments, lectures and more general reading.

It is, however, important that you find a way of doing it that works for you, because note-taking is one of the most effective ways of recording and retaining information.

Further Reading from Skills You Need

The Skills You Need Guide for Students

Develop the skills you need to make the most of your time as a student.

Our eBooks are ideal for students at all stages of education, school, college and university. They are full of easy-to-follow practical information that will help you to learn more effectively and get better grades.

Continue to: Effective Reading Sources of Information

See also: Finding Time for Study Planning an Essay Leveraging AI for Better Note-Taking

- Our Mission

Using Outlines to Support Student Note-Taking

Taking notes on readings doesn’t always come naturally to students, and having a framework to follow helps them focus on what’s most important.

Note-taking is a skill that’s critical to most reading assignments, and sound, thorough notes can help students read for deeper comprehension. The process of encoding that occurs during note-taking forms new pathways in the brain, lodging information more durably in long-term memory. Good notes can go a long way toward preparing students for tests, and they can also help reduce their stress.

But note-taking isn’t a skill that comes naturally to many students. Without explicit instruction, they can struggle to determine what’s relevant or most important—then wind up either trying to write down everything or taking notes that are too scant to be helpful.

Many teachers give students a head start with note-taking for reading assignments by preparing an outline for them that provides structure and guidance, often by including prompts for key points (headings), relevant details (subheadings), and vocabulary. That way, teachers encourage students’ interaction with the material, prevent them from feeling overwhelmed, and build their confidence in their understanding—all of which greases the wheels for learning.

Tips for Creating a Reading Outline

Select content intentionally: The challenge is finding a balance between including too much information and providing too little. As you draft the reading outline, ask yourself questions to stay focused on what’s most important—and to head off overly granular note-taking:

- How does this heading address the content standards or course expectations?

- Which concepts are essential for discussing the main ideas?

- Has this idea already been examined via another heading?

Consider readability: Make the outline easy to follow; it should flow in tandem with the text. Use the same terminology that students see in the text to reinforce new vocabulary. Include specific textbook pages with helpful examples or visuals to encourage students to revisit the text. Use cues (white space, numbered lists, and boldfaced type) so that students have a sense of how much to write and what content to prioritize.

Be consistent: Use a similar structure for each outline so it becomes familiar to your students. That includes the number of pages, headings, and prompts for supporting points. Commit to making the outline available at set times (before the reading, during the reading, or after the reading) and communicating its availability to students in advance. Adhere to a single organizational style, such as providing a complete outline or a partial outline that includes some concepts but requires students to insert the missing information. Use a single writing style—e.g., complete sentences or fragments.

Incorporate active reading strategies: Give students ample opportunities to process new concepts so they can absorb the material they’re reading in different ways—and so you’re creating space for different learning needs. Ask students to rephrase material in their own words (e.g., “How would you explain this concept to a friend?”) and create analogies to explore relationships between key concepts.

Encourage students to make text-text connections (e.g, “Does this term remind you of vocabulary you learned earlier?”) and text-self connections (e.g., “Which characters or events do you most relate to?”). If understanding the reading in front of them depends on their understanding of previous chapters or resources, remind them where to go to refresh their memories. Also, offer additional exposure to the content, such as video links, diagrams, and graphic organizers so that they can absorb the information in different ways.

Plan for challenges: If you notice low performance on practice activities or assessments, encourage the student to share their completed outline early to allow time for feedback. Ask students to share their experience with using reading outlines created by other teachers. Do they always find reading outlines challenging? Are there other note-taking strategies that they’ve found easier to follow? Does the outline method work for them when they’re preparing for tests?

Although most students have had experience working with reading outlines, many may still need guidance and even practice. Provide students with low-stakes opportunities to experiment with adding appropriate information to outlines, such as examples and specific characteristics of key concepts. If you have a student who is hesitant or resistant to using the outline, share with them how the information from the outline can support study methods like flash cards. Consider showing them how content from the outline can be converted into assessment questions.

Evaluate: Assess the effectiveness of your prepared outlines. Observe the types of questions that students ask (factual, analysis, application, etc.) and when (while working on the outline or before an assessment). Consider trends, such as if multiple students leave the same outline areas incomplete, or anomalies, such as if a particular student consistently does not complete particular parts of outlines.

Ultimately, you want to look at the big picture: Does the time you take to prepare reading outlines have a clear positive outcome? That’s the point, after all: that the reading outlines you carefully create help your students with their reading comprehension and test preparation.

Writing Studio

Active reading strategies, active reading strategies, or reading for writing.

In an effort to make our handouts more accessible, we have begun converting our PDF handouts to web pages. Download this page as a PDF: Active Reading Strategies handout PDF Return to Writing Studio Handouts

Reading a text in preparation for an academic writing assignment is different from reading for pleasure, and not just because the content is more serious or scholarly. That’s because writing about a text forces you to think about it and understand it in a different way.

The following strategies can be used individually or in combination with one another to help prepare you for writing about a text you have read.

Recommend Strategies for Active Reading

Before you even turn to page one of your reading assignment, consult a chapter summary, abstract, class notes, or even an online review in order to give you a basic understanding of what the text is going to cover and how.

Keep in mind, of course, that reviews NEVER substitute for the text itself (and some instructors may ask you not to consult outside sources or summaries). If you use any outside sources to prepare to read, jot them down to remember what you have read. Keeping this sort of ‘reading log’ from the beginning gives you an easy way to keep track of and eventually acknowledge any influence they may have had on your eventual writing.

Mark Up the Text

Read with a pen or pencil in hand, and when something grabs your attention, make a note of it on the page right away. This will enable you to record your initial responses, ideas and questions about the text.

Underline, circle, or bracket passages that seem important and note why in the page margins. Post-it notes may prove helpful for jotting down more extensive thoughts. Try using different colored post-its for different kinds of responses.

Marking up the text in this way will help you locate important passages, both during class discussion of a text and later when you are drafting your paper. Of course, your approach should reflect whether you own the text in question. In other words, Post-it notes or something less permanent are the way to go if you are using a book from the library or other borrowed text.

Take Reading Notes

Some students find it helpful to take more detailed notes during the reading process, either in writing or on their computer. This process involves a greater time investment up front, but the reward is a much more detailed record of your thoughts, ideas and questions while reading.

Five-Minute Reflective Writing

Even if you do not take detailed notes while reading, the following five-minute reflective writing exercises undertaken as soon as you finish your reading can be an invaluable way of helping you summarize or synthesize a text you have just read.

- Free-write: Write whatever comes into your mind, uninterrupted and unedited, for five minutes.

- Quick questions: Think about what you found most interesting, important, confusing, unexpected, etc. and generate some questions about what you’ve just read. Then spend a few minutes going back through the text to help you find answers to your questions.

- Summary: Write a single paragraph (5-6 sentences) summarizing what you’ve just read.

- Outline: Make a rough outline of what you’ve just read.

- Quotation bank: Transcribe the passages you find most important and include page numbers for possible use in your paper.

Re-Read, Re-Read, and Re-Read Again!