The Lean Post / Articles / Engaging Physicians to Solve Real Problems in Healthcare

Problem Solving

Engaging Physicians to Solve Real Problems in Healthcare

By Jack Billi

June 24, 2013

Trained in the scientific method, practical to the core, focused on the patient--one would think physicians would be the first adopters of lean thinking and practice, but many healthcare professionals resist learning more about what lean can do for them. Dr. Jack Billi explains why this may be and makes the case for lean in healthcare.

Healthcare grew up as a cottage industry, with notoriously weak process management and unclear responsibilities for costs. As healthcare organizations now strive to fix their broken processes and provide greater value (high quality care at a reasonable cost), one of the barriers often mentioned is ‘difficulty engaging physicians’ in lean improvement.

I just returned from the Lean Healthcare Transformation Summit in Orlando. Lean thinking is spreading rapidly across healthcare organizations in the US and across the globe. Early adopters such as Virginia Mason and ThedaCare have powerfully demonstrated lean’s potential to transform healthcare. Over 200 organizations participated in the 2013 Summit, and we have a long way to go.

Physicians are natural “fixers” who love to solve problems and puzzles. Medical students are selected for this attribute, among others. Future physicians are trained to use the scientific method to diagnose and treat patients’ medical problems. They learn how to make direct observations of the patient, asking questions in a systematic manner, as part of the history and physical exam. Like lean practitioners, physicians are trained to “Grasp the Situation” by systematically observing the work and identifying problems in the gemba .

As physicians, we use scientific problem solving daily when we compare our patient’s findings with known syndromes and diseases, to create a hypothesis about the patient’s tentative diagnosis. We use root cause analysis in our “Impression”, including alternative explanations (“The jaundice might be caused by biliary obstruction or a reaction to a nausea drug”), and in developing a Plan of care (countermeasures). The hypothesis is tested ( Do ) and revised by further diagnostic testing or by response to treatment, a form of Check and Adjust . No physician I know would consider treating or performing surgery on a patient he or she had not personally examined. We must go to the gemba, so to speak.

So if lean thinking is just another version of what physicians do every day in taking care of patients, why don’t all doctors naturally gravitate to lean? Here are some common themes:

- Like nurses, as physicians many of us have had to become “ workaround artists” to get through our day. Doctors perform daily heroics to get their patients the care they need, despite being frequently frustrated by fragmented systems of care and broken processes. Doctors know that the ‘current state’ is deeply flawed, and some have lost hope that they can improve the work.

- Some physicians have developed a deep-seated wariness of corporate improvement programs, having experienced flavor of the month cost efficiency and re-engineering programs. They may cynically believe that lean is just the latest cost cutting program imported from another industry, rather than a path to value creation.

- Lean vocabulary is obscure to newcomers, and the term “ standard work ,” if not properly explained, may be off-putting for physicians. Doctors value using critical thinking skills in service to their patients. They don’t want to practice cookbook medicine, or have someone outside of the profession (e.g., the government or an insurance company…) tell them how best to take care of their patients.

So what’s the prescription for engaging physicians?

Lean is practical to its core. Helping physicians “learn it by doing it” can help overcome resistance. When physicians can see for themselves that scientific problem-solving improves patients’ experience while making it easier for them to do their work, most become converts. For this reason I suggest always scoping a problem or project to ensure it includes some representation or telling of the physician’s pain with the current process.

The bad rap on standard work, I believe, reflects a misunderstanding of what it really is. If standard work is explained to physicians as the best way we know now to practice so as to reliably produce desired results, resistance will melt away. Standard work should be viewed as how we’ve designed our work to consistently deliver safe, effective care. Standard work makes it possible for physicians to apply their creativity to improving work methods. Without standard work, how would anyone know if a change is actually an improvement?

Since lean thinking is essentially the scientific method, practiced through iterative cycles of PDCA , physicians already have the mindset to be lean thinkers. We pride ourselves on practicing evidence-based medicine. Physicians are natural allies in a lean transformation. What’s not to like about a method that makes it easier for the doctor to do his or her job, and do it better? The challenge is to apply the same rigorous thinking we use to work up patient problems to solve the ongoing problems we experience in our organizations.

I wonder how many of my fellow physicians see it the same way?

Written by:

About Jack Billi

Dr. Jack Billi serves as Professor of Internal Medicine and Medical Education at the University of Michigan Medical School, and as Associate Vice President for Medical Affairs of the University of Michigan. He leads the Michigan Quality System, the University of Michigan Health System’s lean transformation strategy. Dr. Billi’s research and management interests include the use of lean thinking to improve quality, safety and efficiency in health care, evidence-based guidelines, population health, clinical practice transformation tied to performance-based differential reimbursement, and conflict of interest management. Billi is active in organized medicine and collaborative quality improvement initiatives in Michigan, and is involved nationally and internationally in developing guidelines and educational programs for cardiac resuscitation.

Thank you! It is rare to find a physician who engages with a patient in the spirit of problem-solving. Too many times a patient is quickly given a standard answer that ignores the many parameters of the situation. It’s much easier and less time-consuming to prescribe something rather than truly investigate.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Revolutionizing Logistics: DHL eCommerce’s Journey Applying Lean Thinking to Automation

Podcast by Matthew Savas

Transforming Corporate Culture: Bestbath’s Approach to Scaling Problem-Solving Capability

Teaching Lean Thinking to Kids: A Conversation with Alan Goodman

Podcast by Alan Goodman and Matthew Savas

Related books

A3 Getting Started Guide

by Lean Enterprise Institute

The Power of Process – A Story of Innovative Lean Process Development

by Eric Ethington and Matt Zayko

Related events

September 26, 2024 | Morgantown, PA or Remond, WA

Building a Lean Operating and Management System

October 02, 2024 | Coach-Led Online OR In-Person (Oakland University in Rochester, MI)

Managing to Learn

Explore topics.

Subscribe to get the very best of lean thinking delivered right to your inbox

Privacy overview.

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

When Health Care Providers Look at Problems from Multiple Perspectives, Patients Benefit

- Jemima A. Frimpong,

- Christopher G. Myers,

- Kathleen M. Sutcliffe,

- Yemeng Lu-Myers

Specialization has its limits.

Health care providers have vastly different ways of seeing and treating patients, as differences in profession, specialty, experience, or background lead them to pay attention to particular signals or cues, and influence how they approach problems. While diverse perspectives and approaches to care are important, if they are not managed appropriately, they can cause misunderstandings, bias decision-making, and get in the way of the best care. Two things can help health professionals get better at communicating with each other and adopting multiple perspectives themselves: 1) creating an environment that supports perspective sharing and effective communication among team members; and 2) building people’s capacity to adopt multiple perspectives.

Mr. Smith was ready to be discharged home after his laryngectomy, an extensive operation that removes a patient’s throat due to cancer. In the opinion of Dr. Lu-Myers, he was a capable man who had passed his physical and occupational therapy evaluations with flying colors. Mr. Smith had fulfilled the doctor’s list of clinical discharge criteria, and she was eager to send him home. She planned to entrust him and his family to manage his dressing changes, as well as his tracheostomy and drain care, with the support of frequent outpatient nursing visits — all very routine protocol, especially for someone who seemed alert and capable.

- Jemima A. Frimpong is an assistant professor at the Johns Hopkins University Carey Business School and Armstrong Institute for Patient Safety & Quality. Her research focuses on the adoption and sustainability of innovations, development and testing of organization-level interventions, and performance improvement, centered primarily on health care organizations.

- Christopher G. Myers is an assistant professor at Johns Hopkins University on the faculty of the Carey Business School, School of Medicine, and Armstrong Institute for Patient Safety & Quality. His research explores interpersonal processes of learning, development, and innovation in health care and other knowledge-intensive work environments. Follow him @ChrisGMyers .

- KS Kathleen M. Sutcliffe is a Bloomberg Distinguished Professor at Johns Hopkins University. Her research examines how organizations manage the unexpected and the dynamics of organizational reliability and resilience.

- Yemeng Lu-Myers is a resident surgeon specializing in otorhinolaryngology (ENT) at the University of Maryland Medical Center. Her research explores how patient demographics influence health outcomes and examines the effects of differential access to care.

Partner Center

Become a Member

Problem Solving

Problem Solving in the Medical Practice Using the Five Whys

Ron Harman King, MS | Neil Baum, MD

December 8, 2018

There is no doctor or medical practice that hasn’t experienced a problem or a crisis in either the care of patients or the business aspect of the practice. Unfortunately, most doctors have few or no skills in crisis management or nonclinical problem solving. This task often is left to the office manager or the practice’s medical director. This article discusses the use of the root cause analysis and how it can be applied to nearly every medical practice. The “five whys” concept is a way to try to find the causes of potentially complex problems. When done properly, this strategy will help you to get to the root cause of many issues so that it can be addressed, rather than just focusing on symptoms of that problem.

When done properly, the “five whys” strategy has been shown not only to be effective, but also to be easy to use on a wide range of issues throughout many medical practices. It also can be combined and used with a variety of other techniques used to identify and solve workplace problems.

The five whys technique, which began in Japan at the Toyota Motor Company, is based on a scientific approach to problem solving. It has been applied through just about every type of industry around the world and could easily be used in the healthcare profession as well.

In the five whys process, you ask “why?” at least five times to get to the root cause of a problem. The process starts out with a problem that is affecting the practice, and then keeps asking why things happened until the root cause of the issue has been identified.

One of the best ways to get a good understanding of the five whys is to look at examples of how it has been explained with an example from the automotive industry. The following example is commonly used—how to discover the root cause of a car that will not start. The initial problem is “The car will not start.” From there, the five whys are asked:

Why won’t the car start? Answer: The battery is dead.

Why is the battery dead? Answer: The alternator is not working properly.

Why isn’t the alternator working? Answer: The serpentine belt has broken.

Why did the serpentine belt break? Answer: It was not replaced when worn.

Why wasn’t it replaced? Answer: The owner did not follow the recommended service schedule.

The last why is considered the root cause of the problem. If the owner of the vehicle had followed the recommended service schedule, this issue would not have happened. Not only that, but following the recommended service schedule will help to prevent a wide range of other problems including a decrease in radiator, brake, and oil fluids.

Applying the Five Whys Process to the Healthcare Practice

The problem to be solved is the practice is running behind schedule:

Why is the practice already one hour behind schedule in seeing patients by mid-morning when the doctor is supposed to start seeing patients at 9:00 AM? Answer: Patients are arriving 30 to 60 minutes late for their appointments.

Why are patients showing up late for their appointments? Answer: The doctor is usually 30 to 60 minutes late, and patients don’t want to wait to be seen so they arrive and check in 30 to 60 minutes after their designated appointment times.

Why is the doctor 30 to 60 minutes late by mid-morning? Answer: The doctor arrives for his office clinic 30 minutes late because patients usually are not taken to the exam rooms until 9:30. Instead the doctor goes to the computer to check e-mails.

Why are patients put in the rooms 30 minutes after their appointment times? Answer: The staff doesn’t arrive until 8:30 and is not ready to place patients in the rooms until 9:30.

Why is the lab data previously ordered not placed in the chart or recorded on the electronic medical record causing delays making decisions regarding patient care? Answer: The results have been sent to the office via fax but not recorded in the patient’s cart.

Solution: Start the day at 8:00 A.M. and start putting patients in the room at 8:45. Inform the doctor that he or she should arrive in the office by at least 8:45, allowing a few minutes to look at the computer, and that patients are to be seen starting promptly at 9:00.

Finding the Root Cause

The primary goal of the five whys is to take a problem and find the root cause so a solution can be identified and put in place. When done properly, a practice can find the root cause of most problems so that they can take actions to prevent it from happening in the future.

One of the best things about the five whys is that it is inexpensive to implement. A medical practice or a hospital can begin using it without added expense. The only cost is the time required to go through the process.

Why Look for the Root Cause

Most medical practices solve problems by identifying a problem and then using a quick fix for prompt resolution. In the long run, it is much better to identify the root cause of the issue and fix it—that will prevent the problem from occurring again. Seeking a root cause solution rather than just addressing the symptoms allows the practice to reduce recurrence (by dealing with the root cause, the symptoms are less likely to happen again in the future); prevent problems before they occur; gather information that identifies other issues that are impacting the practice; and place an emphasis on quality and safety over speed by avoiding a quick fix that temporarily solves the problem.

Every practice is unique, and all workplaces have their own set of problems that need to be dealt with. Implementing the use of the five whys can help medical practices to better understand their issues, and give them a clear roadmap on how those issues can be addressed permanently.

Getting Started with the Five Whys

The five whys system can be customized based on the specific needs of a given practice. Most practices or hospitals that are implementing this type of strategy will use some general rules or guidelines that can help keep the strategy focused on finding the root cause of the problem. Here are a few rules of performing the five whys:

Form the questions from the patient’s point of view. For example, when the practice runs behind schedule, patients are not happy that they are being seen 60 or even 90 minutes after their designated appointment. Another example would be that patients complain that they don’t receive results of lab tests or imaging studies until two or three weeks after the test or the procedure.

Keep asking or drilling until the root cause is discovered (even if more than five whys are required). This strategy is looking to find the root cause of the problem, not to place blame on any person(s) in the practice.

Base all statements on facts, not assumptions or hearsay.

Make sure to clearly distinguish the causes of problems from the symptoms of the problem (example: Doctor doesn’t start on time is a problem; Patients are upset is a symptom).

Involve physicians, nurses, administration, and ancillary personal as needed.

Focus on long-term success rather than short-term or quick-fix solutions.

Write down the problem at the top of a white board or flip chart and make sure that everyone understands the problem.

Try to make your answers concise and precise.

Be patient and don’t jump to conclusions.

Focus on the process, not on finding someone to blame.

Perform a root cause analysis as soon as possible after the error or variance occurs; otherwise, important details may be missed.

Explain that the purpose of the root cause analysis process is to focus on fixing or correcting the error and the systems involved. Make a point of stressing that the purpose of the analysis is not to assign blame but to solve problems.

Ask the question “Why?” until the root cause is determined. It is important to understand that in healthcare there may be more than one root cause for an event or a problem. The difficult part of identifying the root cause often requires persistence.

Finally, after the root cause is identified, conclude with the solution that will prevent the error from occurring again

It is this last step—identifying corrective action(s)—that will prevent recurrence of the problem that initially started the analysis. It is necessary to check that each corrective action, if it were to be implemented, is likely to reduce or prevent the specific problem from occurring.

The purpose of identifying solutions to a problem is to prevent recurrence. If there are alternative solutions that are equally effective, then the simplest or lowest-cost approach is preferred.

It is important that the group that identifies the solutions that will be implemented agrees on those solutions. Obtaining a consensus of the group that all are in agreement before solutions are implemented is important. You want to make every effort not to introduce or create a new problem that is worse than the original issue that you were attempting to solve.

The primary aims of root cause analysis are:

To identify the factors that caused the problem that may even result in harmful outcomes;

To determine what behaviors, actions, inactions, or conditions need to be changed;

To prevent recurrence of similar and perhaps harmful outcomes; and

To identify solutions that will promote the achievement of better outcomes and improved patient satisfaction.

To be effective, root cause analysis must be performed systematically using the five whys to drill down to the seminal event that initiates or produces the problem. The best result occurs when the root cause is identified and then backed up by documented evidence. For this systematic process to succeed, a team effort is typically required.

Bottom Line: Root cause analysis can help transform a reactive culture or one that moves from one crisis to the next into a forward-looking culture or a practice that solves problems before they occur or escalate into a full-blown crisis. More importantly, a practice that uses the five whys/root cause analysis reduces the frequency of problems occurring over time.

Strategic Perspective

Action Orientation

This article is available to AAPL Members.

Log in to view., career & learning, leadership library, membership & community, for over 45 years..

The American Association for Physician Leadership has helped physicians develop their leadership skills through education, career development, thought leadership and community building.

The American Association for Physician Leadership (AAPL) changed its name from the American College of Physician Executives (ACPE) in 2014. We may have changed our name, but we are the same organization that has been serving physician leaders since 1975.

CONNECT WITH US

Looking to engage your staff.

AAPL providers leadership development programs designed to retain valuable team members and improve patient outcomes.

American Association for Physician Leadership®

formerly known as the American College of Physician Executives (ACPE)

Privacy Policy | Advertising Kit | Press Room

You are using an outdated browser

Unfortunately Ausmed.com does not support your browser. Please upgrade your browser to continue.

Cultivating Critical Thinking in Healthcare

Published: 06 January 2019

Critical thinking skills have been linked to improved patient outcomes, better quality patient care and improved safety outcomes in healthcare (Jacob et al. 2017).

Given this, it's necessary for educators in healthcare to stimulate and lead further dialogue about how these skills are taught , assessed and integrated into the design and development of staff and nurse education and training programs (Papp et al. 2014).

So, what exactly is critical thinking and how can healthcare educators cultivate it amongst their staff?

What is Critical Thinking?

In general terms, ‘ critical thinking ’ is often used, and perhaps confused, with problem-solving and clinical decision-making skills .

In practice, however, problem-solving tends to focus on the identification and resolution of a problem, whilst critical thinking goes beyond this to incorporate asking skilled questions and critiquing solutions .

Several formal definitions of critical thinking can be found in literature, but in the view of Kahlke and Eva (2018), most of these definitions have limitations. That said, Papp et al. (2014) offer a useful starting point, suggesting that critical thinking is:

‘The ability to apply higher order cognitive skills and the disposition to be deliberate about thinking that leads to action that is logical and appropriate.’

The Foundation for Critical Thinking (2017) expands on this and suggests that:

‘Critical thinking is that mode of thinking, about any subject, content, or problem, in which the thinker improves the quality of his or her thinking by skillfully analysing, assessing, and reconstructing it.’

They go on to suggest that critical thinking is:

- Self-directed

- Self-disciplined

- Self-monitored

- Self-corrective.

Key Qualities and Characteristics of a Critical Thinker

Given that critical thinking is a process that encompasses conceptualisation , application , analysis , synthesis , evaluation and reflection , what qualities should be expected from a critical thinker?

In answering this question, Fortepiani (2018) suggests that critical thinkers should be able to:

- Formulate clear and precise questions

- Gather, assess and interpret relevant information

- Reach relevant well-reasoned conclusions and solutions

- Think open-mindedly, recognising their own assumptions

- Communicate effectively with others on solutions to complex problems.

All of these qualities are important, however, good communication skills are generally considered to be the bedrock of critical thinking. Why? Because they help to create a dialogue that invites questions, reflections and an open-minded approach, as well as generating a positive learning environment needed to support all forms of communication.

Lippincott Solutions (2018) outlines a broad spectrum of characteristics attributed to strong critical thinkers. They include:

- Inquisitiveness with regard to a wide range of issues

- A concern to become and remain well-informed

- Alertness to opportunities to use critical thinking

- Self-confidence in one’s own abilities to reason

- Open mindedness regarding divergent world views

- Flexibility in considering alternatives and opinions

- Understanding the opinions of other people

- Fair-mindedness in appraising reasoning

- Honesty in facing one’s own biases, prejudices, stereotypes or egocentric tendencies

- A willingness to reconsider and revise views where honest reflection suggests that change is warranted.

Papp et al. (2014) also helpfully suggest that the following five milestones can be used as a guide to help develop competency in critical thinking:

Stage 1: Unreflective Thinker

At this stage, the unreflective thinker can’t examine their own actions and cognitive processes and is unaware of different approaches to thinking.

Stage 2: Beginning Critical Thinker

Here, the learner begins to think critically and starts to recognise cognitive differences in other people. However, external motivation is needed to sustain reflection on the learners’ own thought processes.

Stage 3: Practicing Critical Thinker

By now, the learner is familiar with their own thinking processes and makes a conscious effort to practice critical thinking.

Stage 4: Advanced Critical Thinker

As an advanced critical thinker, the learner is able to identify different cognitive processes and consciously uses critical thinking skills.

Stage 5: Accomplished Critical Thinker

At this stage, the skilled critical thinker can take charge of their thinking and habitually monitors, revises and rethinks approaches for continual improvement of their cognitive strategies.

Facilitating Critical Thinking in Healthcare

A common challenge for many educators and facilitators in healthcare is encouraging students to move away from passive learning towards active learning situations that require critical thinking skills.

Just as there are similarities among the definitions of critical thinking across subject areas and levels, there are also several generally recognised hallmarks of teaching for critical thinking . These include:

- Promoting interaction among students as they learn

- Asking open ended questions that do not assume one right answer

- Allowing sufficient time to reflect on the questions asked or problems posed

- Teaching for transfer - helping learners to see how a newly acquired skill can apply to other situations and experiences.

(Lippincott Solutions 2018)

Snyder and Snyder (2008) also make the point that it’s helpful for educators and facilitators to be aware of any initial resistance that learners may have and try to guide them through the process. They should aim to create a learning environment where learners can feel comfortable thinking through an answer rather than simply having an answer given to them.

Examples include using peer coaching techniques , mentoring or preceptorship to engage students in active learning and critical thinking skills, or integrating project-based learning activities that require students to apply their knowledge in a realistic healthcare environment.

Carvalhoa et al. (2017) also advocate problem-based learning as a widely used and successful way of stimulating critical thinking skills in the learner. This view is echoed by Tsui-Mei (2015), who notes that critical thinking, systematic analysis and curiosity significantly improve after practice-based learning .

Integrating Critical Thinking Skills Into Curriculum Design

Most educators agree that critical thinking can’t easily be developed if the program curriculum is not designed to support it. This means that a deep understanding of the nature and value of critical thinking skills needs to be present from the outset of the curriculum design process , and not just bolted on as an afterthought.

In the view of Fortepiani (2018), critical thinking skills can be summarised by the statement that 'thinking is driven by questions', which means that teaching materials need to be designed in such a way as to encourage students to expand their learning by asking questions that generate further questions and stimulate the thinking process. Ideal questions are those that:

- Embrace complexity

- Challenge assumptions and points of view

- Question the source of information

- Explore variable interpretations and potential implications of information.

To put it another way, asking questions with limiting, thought-stopping answers inhibits the development of critical thinking. This means that educators must ideally be critical thinkers themselves .

Drawing these threads together, The Foundation for Critical Thinking (2017) offers us a simple reminder that even though it’s human nature to be ‘thinking’ most of the time, most thoughts, if not guided and structured, tend to be biased, distorted, partial, uninformed or even prejudiced.

They also note that the quality of work depends precisely on the quality of the practitioners’ thought processes. Given that practitioners are being asked to meet the challenge of ever more complex care, the importance of cultivating critical thinking skills, alongside advanced problem-solving skills , seems to be taking on new importance.

Additional Resources

- The Emotionally Intelligent Nurse | Ausmed Article

- Refining Competency-Based Assessment | Ausmed Article

- Socratic Questioning in Healthcare | Ausmed Article

- Carvalhoa, D P S R P et al. 2017, 'Strategies Used for the Promotion of Critical Thinking in Nursing Undergraduate Education: A Systematic Review', Nurse Education Today , vol. 57, pp. 103-10, viewed 7 December 2018, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0260691717301715

- Fortepiani, L A 2017, 'Critical Thinking or Traditional Teaching For Health Professionals', PECOP Blog , 16 January, viewed 7 December 2018, https://blog.lifescitrc.org/pecop/2017/01/16/critical-thinking-or-traditional-teaching-for-health-professions/

- Jacob, E, Duffield, C & Jacob, D 2017, 'A Protocol For the Development of a Critical Thinking Assessment Tool for Nurses Using a Delphi Technique', Journal of Advanced Nursing, vol. 73, no. 8, pp. 1982-1988, viewed 7 December 2018, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jan.13306

- Kahlke, R & Eva, K 2018, 'Constructing Critical Thinking in Health Professional Education', Perspectives on Medical Education , vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 156-165, viewed 7 December 2018, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40037-018-0415-z

- Lippincott Solutions 2018, 'Turning New Nurses Into Critical Thinkers', Lippincott Solutions , viewed 10 December 2018, https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/expert-insights/turning-new-nurses-into-critical-thinkers

- Papp, K K 2014, 'Milestones of Critical Thinking: A Developmental Model for Medicine and Nursing', Academic Medicine , vol. 89, no. 5, pp. 715-720, https://journals.lww.com/academicmedicine/Fulltext/2014/05000/Milestones_of_Critical_Thinking___A_Developmental.14.aspx

- Snyder, L G & Snyder, M J 2008, 'Teaching Critical Thinking and Problem Solving Skills', The Delta Pi Epsilon Journal , vol. L, no. 2, pp. 90-99, viewed 7 December 2018, https://dme.childrenshospital.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Optional-_Teaching-Critical-Thinking-and-Problem-Solving-Skills.pdf

- The Foundation for Critical Thinking 2017, Defining Critical Thinking , The Foundation for Critical Thinking, viewed 7 December 2018, https://www.criticalthinking.org/pages/our-conception-of-critical-thinking/411

- Tsui-Mei, H, Lee-Chun, H & Chen-Ju MSN, K 2015, 'How Mental Health Nurses Improve Their Critical Thinking Through Problem-Based Learning', Journal for Nurses in Professional Development , vol. 31, no. 3, pp. 170-175, viewed 7 December 2018, https://journals.lww.com/jnsdonline/Abstract/2015/05000/How_Mental_Health_Nurses_Improve_Their_Critical.8.aspx

Anne Watkins View profile

Help and feedback, publications.

Ausmed Education is a Trusted Information Partner of Healthdirect Australia. Verify here .

- About this site

- Curricular Affairs Contact

- FID Philosophy

- Faculty Mentoring

- Educational Program Objectives

- ARiM Initiatives

- Faculty Support

- Active Learning Theory

- Curriculum Development

- Developmental Learning Theory

- Peer Review of Teaching

- Resources & Strategies

- Flipped Learning

- Teaching Guides

- Educational Strategies

- Large Group Sessions

- Team Learning

- Constructive Feedback

- Ed Tech & Training

- Med Ed Distinction Track

- Affiliate Clinical Faculty

- Faculty Instructional Development Series

- Microskills 1-Min Preceptor

- BDA for Teaching

- Med Ed Resources

- RIME Framework

- WBA in Clerkship

- About Instructional Tech

- Software Worth Using

- Apps for Learning

- Apps for Teaching

- Apps for Research

- Copyright Resources

- Application Online

- Program Goals

- Program Competence Areas

- Program Timeline

- Program Activities

- Projects & Presentations

- Participants

- SOS Series Calendar

- Presentation Tools

- Communication Tools

- Data Collection & Analysis

- Document Preparation

- Project Management Tools

You are here

Medical problem solving.

Medical problem-solving skills are essential to learning how to develop an effective differential diagnosis in an efficient manner, as well as how to engage in the reflective practice of medicine. Students' experience in CBI complements the clinical reasoning skills they learn through the UA COM Doctor and Patient course and through their Societies mentors.

The UA COM medical problem-solving structure applies the B-D-A ( Before-During-After) framework as an educational strategy. Thus, CBI requires students to engage in reflection before, during and following facilitated sessions. Reflection contributes to improvement in problem-solving skills and helps medical students cultivate a habit of reflection that will serve them well as they become lifelong professional learners.

As with medical-problem solving, practice-based learning (learning through experience) requires students to engage in reflection before, during and following each learning experiences. Reflection contributes to improvement in problem-solving skills and cultivating a habit of reflection will serve medical students well as they become lifelong professional learners.

Related Resources

B-D-A Framework Reflective Learning Guide Cognitive Error Quick Guide

- MedMal by Coverys

- Industry News

- Access and Reimbursement

- Law & Malpractice

- Coding & Documentation

- Practice Management

- Patient Engagement & Communications

- Billing & Collections

- Staffing & Salary

Eight-Step Problem Solving Process for Medical Practices

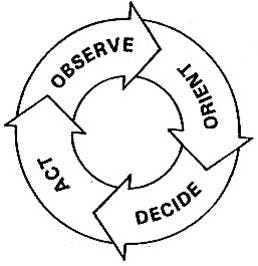

Whether you are hoping to solve a problem at your practice or simply trying to improve a process, the easy-to-follow OODA Loop method can help.

Practice managers know that there are four key objectives at the core of process improvement:

• To remove waste and inefficiencies • To increase productivity and asset availability • To improve response time and agility • To sustain safe and reliable operations

The question is, how do we do all this? I would suggest a proven technique known as the OODA Loop.

How to talk with patients about billing

If you let patients know from the start what you expect from them, you’re far more likely to get the money you’re asking for.

Practice Administration Stability and Key Determinants of Success

Sachin Gupta, CEO of IKS Health, discusses how independent practices can remain administratively stable during the pandemic and after, as well as provides the key determinants of success for new and growing practices.

Practice tip of the week: How to create an operations manual for your practice

Your weekly dose of wisdom from the Physicians Practice experts.

When Physicians are Owners AND Employees

The professional model of medicine is trying to reach a sweet spot, allowing physicians to remain independent but maximize the power of a larger organization.

Most read 2022: 10 Small ways to provide great customer service to patients

Providing great customer service at your medical practice boosts revenue and patient satisfaction. Here are 10 tips.

Two things every standout healthcare manager does

The managerial role, which historically emphasized operational knowledge and experience is now demanding the familiarity of clinical operations as well.

2 Commerce Drive Cranbury, NJ 08512

609-716-7777

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- News & Views

- Critical thinking in...

Critical Thinking in medical education: When and How?

Rapid response to:

Critical thinking in healthcare and education

- Related content

- Article metrics

- Rapid responses

Rapid Response:

Critical thinking is an essential cognitive skill for the individuals involved in various healthcare domains such as doctors, nurses, lab assistants, patients and so on, as is emphasized by the Authors. Recent evidence suggests that critical thinking is being perceived/evaluated as a domain-general construct and it is less distinguishable from that of general cognitive abilities [1].

People cannot think critically about topics for which they have little knowledge. Critical thinking should be viewed as a domain-specific construct that evolves as an individual acquires domain-specific knowledge [1]. For instance, most common people have no basis for prioritizing patients in the emergency department to be shifted to the only bed available in the intensive care unit. Medical professionals who could thinking critically in their own discipline would have difficulty thinking critically about problems in other fields. Therefore, ‘domain-general’ critical thinking training and evaluation could be non-specific and might not benefit the targeted domain i.e. medical profession.

Moreover, the literature does not demonstrate that it is possible to train universally effective critical thinking skills [1]. As medical teachers, we can start building up student’s critical thinking skill by contingent teaching-learning environment wherein one should encourage reasoning and analytics, problem solving abilities and welcome new ideas and opinions [2]. But at the same time, one should continue rather tapering the critical skills as one ascends towards a specialty, thereby targeting ‘domain-specific’ critical thinking.

For the benefit of healthcare, tools for training and evaluating ‘domain-specific’ critical thinking should be developed for each of the professional knowledge domains such as doctors, nurses, lab technicians and so on. As the Authors rightly pointed out, this humongous task can be accomplished only with cross border collaboration among cognitive neuroscientists, psychologists, medical education experts and medical professionals.

References 1. National Research Council. (2011). Assessing 21st Century Skills: Summary of a Workshop. J.A. Koenig, Rapporteur. Committee on the Assessment of 21st Century Skills. Board on Testing and Assessment, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. 2. Mafakheri Laleh M, Mohammadimehr M, Zargar Balaye Jame S. Designing a model for critical thinking development in AJA University of Medical Sciences. J Adv Med Educ Prof. 2016 Oct;4(4):179–87.

Competing interests: No competing interests

Professional Skills

- Jul 31, 2023

- 14 min read

20 Essential Skills Needed to Be a Doctor

20 CCs of awesomeness, STAT!

Siôn Phillpott

Career & Entrepreneurship Expert

Reviewed by Chris Leitch

Choosing to become a doctor isn’t a decision to be taken lightly. After all, it takes a lot of dedication and preparation to even be accepted into medical school . And once you’re there, you’ll be subjected to an intense learning schedule that will take up the majority of your peak years.

To put it mildly: it’s not a career path for the light-hearted — or light-headed.

If you have the correct adeptness, though, it’s also a highly rewarding job, both in terms of satisfaction and financial recompense. To give you an indication of the kind of skills needed to be a doctor , we’ve compiled a brief list.

This is what you’ll need to make it as a physician.

Soft skills

To become a good doctor, you need to develop a range of soft skills , ranging from effective communication to problem solving, and beyond. We’ll talk about 10 of these skills below and see how each relates back to the medical profession:

1. Communication skills

Communication is important in every career, but none more so than in medicine.

Interacting with patients and colleagues will form a huge part of your day-to-day program. And if you have poor communicative skills , not only will it make your job harder but it can also put people’s lives at risk.

For example, communication is a key part of initial diagnosis. Tests and scans can confirm or rule out certain theories, but in order to understand what’s going on with a patient, you need to be able to ask the right questions, read between the lines with their answers and convey to them in simple terms what your thoughts are. Likewise, you need to be able to understand what other professionals (such as nurses , paramedics or pharmacists ) are telling you and give them clear directions in return.

Remember: you can be the brightest academic or the most skilled physician in the business, but if you can’t effectively talk and listen to others, then you — and your patients — are going to struggle.

2. Emotional intelligence

In a similar vein, the ability to display tact and sensitivity — especially with patients — is another key skill.

Unfortunately, it’s a harsh reality of the job that, sometimes, you’re going to have to deliver bad news, either directly to patients or their close relatives. Often, it will be news that the recipient doesn’t want to hear, and you need to have the emotional maturity to remain professional and level-headed and explain to people what the best course of action is.

You may, for example, be informing a total stranger that their wife or husband has been in a life-changing accident, or revealing to a patient that they have a terminal illness. These are hugely difficult conversations that require empathy, professionalism and understanding.

3. Problem-solving skills

Much of medical diagnosis is essentially detective work, gathering clues and evidence, and then working towards a cause and solution. Therefore, it helps if you’re a natural problem solver .

Of course, your training will provide you with the technical knowledge you need to understand such cases, but the ability to decompose problems and construct an internal algorithm that implements that knowledge is a skill that needs to be cultivated and developed.

You’ll need to be able to think outside the box, too. Not every patient presentation is clear-cut, and the test results might not align with your assumptions. In such instances, don’t be afraid to get in touch with your inner Gregory House and approach the problem from a different perspective.

4. Attention to detail

When dealing with drug doses, patient histories, allergies, physiological differences, cultural customs and every other single aspect of a busy hospital ward, it’s naturally imperative that you don’t neglect the little things. In other words, attention to detail is an essential skill for any medical professional .

It’s not just about getting dosages right or being aware of drug contraindications, either; it’s about noticing red flags and leaving no stone unturned in your initial patient interactions. For example, if a certain patient keeps presenting every few months with new injuries, it might be clumsiness — or it could be something more sinister. The point is that good doctors notice everything — even at the end of a long and busy day — and they don’t allow anything to get past them.

5. Decision-making skills

When it comes to patient care, all final clinical decisions are the remit of doctors; therefore, you’re going to need to be comfortable taking responsibility and making tough calls. This means managing and overseeing patient treatment plans, as well as having to explain and justify them to relatives — this can be difficult if they’re not cooperative to your ideas.

It also means being able to make snap decisions . If you work in the emergency department, for example, you may have a patient who is fine one moment and arresting the next. Being able to remain cool, calm and professional under intense pressure — and make sound clinical calls — is the hallmark of a good doctor.

6. Professionalism

Dealing with the public isn’t easy at the best of times, but when they’re stressed, sick, emotional or all three, things can turn chaotic very easily. It’s absolutely vital that you’re able to remain professional at all times and not put yourself in a position where your ability to treat is compromised.

Of course, there are many forms of professionalism; day to day, these are likely to include:

- Not rising to verbal or even physical abuse, and demonstrating strong conflict resolution skills

- Treating all patients courteously and respectfully, regardless their background

- Making patients with potentially embarrassing symptoms comfortable

- Ensuring that high standards of care and correct clinical procedures are maintained and followed at all times, by both yourself and others

- Showing tact and emotional maturity in interactions with patients

7. Teamwork skills

One of the key requirements for any medical professional is the ability to collaborate and work as part of a wider team. This might be in an acute setting (such as in a trauma team or an out-of-hospital setting), or it could be within the wider treatment system where you’re giving and receiving input from other professionals such as psychiatrists or oncologists.

Either way, the ability to interact and build relationships with peers and colleagues is important, not just for patient care but also to ensure a harmonious working environment day in and day out. It’s true that no doctor can achieve anything without good nurses and vice versa, so it’s vital to be a team player at all times.

8. Leadership skills

As previously touched upon, at some point you’re going to be the go-to person when it comes to clinical calls. This might be in the middle of a volatile and highly charged acute emergency, or it might be in regards to a particularly complex ongoing case. Either way, people will be looking to you for guidance and answers, so you need to step up to the plate.

Later on in your career, you’ll likely also be responsible for training and mentoring junior doctors and medical students, so your leadership skills need to be up to scratch. This doesn’t just mean imparting nuggets of wisdom on impressionable minds, either; it means leading by example and being there for others when things don’t go well.

9. Resilience

Admittedly, resilience is not so much a skill as a quality, but it’s still possible to train yourself to be more robust . You will need to, as well, as becoming a doctor means exposing yourself to things that will undeniably have an impact on your worldview and your sensitivities.

From a very early part of your career, you’ll see things that will upset you and change you, and while you will receive all the support you need to process and deal with this, it’s a reality that some people react better than others. If you’re easily upset or shaken by things, then this isn’t necessarily a bad trait — it shows that you’re compassionate, after all — but you’ll need to learn to manage this and ensure that it never affects your professionalism, judgement or your ability to treat.

10. Capacity for learning

Human bodies are immensely complex to the point where it’s near impossible for one person to know everything about them; doctors, however, have to get pretty damn close.

Of course, you don’t need to be a walking encyclopedia; you can always consult specialists and, well, actual medical encyclopedias. But throughout medical school and, indeed, the rest of your career, you’re going to be taking on and absorbing absolutely massive amounts of technical information. If you’re not particularly “book smart”, then there’s a high chance that, at some point, it’s going to catch up with you and you’re going to fall by the wayside.

You’ll never truly leave the classroom, either. Medical discoveries and technologies move quickly, so even as a highly qualified professional, you’ll need to be up to date and aware of the latest treatment developments and trends.

Technical skills

Besides well-developed soft skills, a doctor’s profession requires various technical skills. Unlike soft skills, which can be transferred between jobs and industries , these skills are specific to the medical industry. Let’s talk about 10 technical skills needed to become a doctor:

1. Human anatomy knowledge

Starting with the most obvious one, doctors need to have an excellent understanding of human anatomy. Though the average person might not know exactly where their gallbladder is or what the iliotibial band does, they’ll want their doctor to know so they can diagnose and treat them.

But human anatomy goes beyond what each organ does and where it lies. It involves the study of the various organ systems in the body, of which there are 11 — such as the skeletal and cardiovascular systems — and the understanding of how these systems work together and impact one another.

2. Symptomatology

The human body is complicated. Sometimes, pain in a particular spot on the body can signal that there’s something wrong with whatever organ or muscle lies in that area. However, things aren’t always that straightforward: discomfort in one part of the body can mean an issue somewhere else. On top of that, different conditions and illnesses can have a range of symptoms, not all of which might be present in a patient.

A doctor, therefore, needs to not only be able to recognize and interpret isolated or combined symptoms, they must also take into consideration the patient’s history to rule things out or decide what to investigate further.

3. Measuring vital signs

Vital signs give physicians an indication of a patient’s overall health, helping them detect and monitor problems.

As a physician, you’ll be taught how to measure vital signs manually or using equipment. These fall into four main categories:

- Body temperature , which is most commonly measured orally, rectally or under the armpit, and informs the doctor of fever or hypothermia.

- Respiration rate , which is the number of breaths taken per minute and can point to illnesses and other conditions.

- Pulse rate , which can easily be taken at the wrist and can help diagnose heart conditions, like tachycardia, and other diseases.

- Blood pressure , measured using sphygmomanometers, which can warn of grave health risks such as heart attack and stroke.

4. Wound care

As a doctor, you need to know how to clean and disinfect cuts and lesions, safely wrap up wounds with bandages, and decide on the right aftercare instructions. In the case of a sprain or fracture, you must also be able to apply splints and suggest the right resting period for your patient’s body to heal.

Of course, in some cases, you may be called to give instructions or make assessments over the phone, in case someone needs immediate relief until they can speak with you in person.

In any case, it’s important to know the ingredients of various topical creams and to check whether they’re suitable for your patient given their history.

5. Drawing blood

Also known as venipuncture, drawing blood is an essential skill taught to medical students in school and during their residency. However, physicians don’t tend to draw blood or start IVs often, as those procedures are more routinely carried out by nurses and phlebotomists .

Having said that, some cases do require physicians to step in. For example, when veins in the arms can’t be accessed due to a patient being severely dehydrated, obese or having a history of drug abuse, physicians can make the call and utilize veins in the neck, chest or groin.

6. Giving injections

There are two ways to give an injection: subcutaneously, which means into the fatty tissue beneath the skin, or intramuscularly, which means into the muscle.

For the average person, all injections seem to be done in more or less the same way. As a healthcare professional, however, you’ll know to eliminate air bubbles from the syringe, check the amount of medicine in it, and pay attention to the angle and speed at which the needle enters the patient’s skin.

According to the American CPR Care Association , all doctors must earn CPR certification and keep their knowledge and skills current. The same goes for nurses and other healthcare professionals. As a result, CPR certification remains valid for two years.

Although it makes sense for people to assume that cardiopulmonary resuscitation guidelines stay the same over time, updates to procedures can and do occur. This might have to do with optimizing methods — such as the rate of compressions — as we learn more about the human body, or adapting to events like the COVID-19 pandemic , which came with a set of guidelines of its own.

So, if a career in medicine is calling your name, prepare for a good amount of ongoing learning .

8. Medical reporting

A doctor’s daily life includes assessing patients’ conditions and prescribing the appropriate medications or treatments. Besides keeping records regarding patients’ health for private use, however, physicians are sometimes tasked with filling in medical reports for others. This can happen for various reasons: a patient’s employer or insurance company might require one, for example, or solicitors or police officers may request reports as part of a case.

To write up medical reports as a physician, you need to refer to patients’ previous medical records and make comments that fall under your area of expertise only. This ensures that the end result is clear, detailed and backed by facts rather than informed by memory or opinions.

9. Reading medical imaging

When it comes to treating and preventing conditions and safeguarding people’s health, modern medicine relies on imaging a lot. This refers to scans like X-rays, MRIs, and ultrasound and CT scans.

Though anyone can look at an image of a twisted finger and tell that it’s broken, as a doctor, you’ll need to know how to interpret different types of images and specialized reports. This helps in explaining things to patients and arriving at informed conclusions about their condition, combining evidence from one or more reports.

10. Healthcare software

Healthcare institutions and private medical practices alike make use of different software, like databases and spreadsheets, in order to provide the best possible service to patients. While some (like Excel ) aren’t specialized, doctors often have to familiarize themselves with programs made specifically for the needs of their profession.

These include software for creating and maintaining electronic health records, practice management programs, medical billing software, and programs with telemedicine functionality, to name a few. Often, healthcare software combines a lot of these features into one.

Final thoughts

Of the many difficult steps involved in becoming a doctor, developing these skills can sometimes be overlooked in favor of passing exams and mastering techniques. But without them, your career in medicine will be doomed to failure before it has even begun.

If you’re seriously considering going into the profession, then look at how you can work on these skills, particularly if you think you’re weak in certain areas; medical school boards will assess them, and the challenges and situations you encounter in your career will definitely test them. Not only will you be preparing yourself for your chosen role, but you’ll also be indirectly ensuring that the patients you’ll one day treat will benefit from the professional skill set that you possess.

Are there any other important skills? Let us know in the comments section below!

Originally published on February 6, 2019. Updated by Electra Michaelidou.

Soft Skills

Career Exploration

Technical Skills

Medical Student Guide For Critical Thinking

Critical thinking is an essential cognitive skill for every individual but is a crucial component for healthcare professionals such as doctors, nurses and dentists. It is a skill that should be developed and trained, not just during your career as a doctor, but before that when you are still a medical student.

To be more effective in their studies, students must think their way through abstract problems, work in teams and separate high quality from low quality information. These are the same qualities that today's medical students are supposed to possess regardless of whether they graduate in the UK or study medicine in Europe .

In both well-defined and ill-defined medical emergencies, doctors are expected to make competent decisions. Critical thinking can help medical students and doctors achieve improved productivity, better clinical decision making, higher grades and much more.

This article will explain why critical thinking is a must for people in the medical field.

Definition of Critical Thinking

You can find a variety of definitions of Critical Thinking (CT). It is a term that goes back to the Ancient Greek philosopher Socrates and his teaching practice and vision. Critical thinking and its meaning have changed over the years, but at its core always will be the pursuit of proper judgment.

We can agree on one thing. Critical thinkers question every idea, assumption, and possibility rather than accepting them at once.

The most basic definition of CT is provided by Beyer (1995):

"Critical thinking means making reasoned judgements."

In other words, it is the ability to think logically about what to do and/or believe. It also includes the ability to think critically and independently. CT is the process of identifying, analysing, and then making decisions about a particular topic, advice, opinion or challenge that we are facing.

Steps to critical thinking

There is no universal standard for becoming a critical thinker. It is more like a unique journey for each individual. But as a medical student, you have already so much going on in your academic and personal life. This is why we created a list with 6 steps that will help you develop the necessary skills for critical thinking.

1. Determine the issue or question

The first step is to answer the following questions:

- What is the problem?

- Why is it important?

- Why do we need to find a solution?

- Who is involved?

By answering them, you will define the situation and acquire a deeper understanding of the problem and of any factors that may impact it.

Only after you have a clear picture of the issue and people involved can you start to dive deeper into the problem and search for a solution.

2. Research

Nowadays, we are flooded with information. We have an unlimited source of knowledge – the Internet.

Before choosing which medical schools to apply to, most applicants researched their desired schools online. Some of the areas you might have researched include:

- If the degree is recognised worldwide

- Tuition fees

- Living costs

- Entry requirements

- Competition for entry

- Number of exams

- Programme style

Having done the research, you were able to make an informed decision about your medical future based on the gathered information. Our list may be a little different to yours but that's okay. You know what factors are most important and relevant to you as a person.

The process you followed when choosing which medical school to apply to also applies to step 2 of critical thinking. As a medical student and doctor, you will face situations when you have to compare different arguments and opinions about an issue. Independent research is the key to the right clinical decisions. Medical and dentistry students have to be especially careful when learning from online sources. You shouldn't believe everything you read and take it as the absolute truth. So, here is what you need to do when facing a medical/study argument:

- Gather relevant information from all available reputable sources

- Pay attention to the salient points

- Evaluate the quality of the information and the level of evidence (is it just an opinion, or is it based upon a clinical trial?)

Once you have all the information needed, you can start the process of analysing it. It’s helpful to write down the strong and weak points of the various recommendations and identify the most evidence-based approach.

Here is an example of a comparison between two online course platforms , which shows their respective strengths and weaknesses.

When recommendations or conclusions are contradictory, you will need to make a judgement call on which point of view has the strongest level of evidence to back it up. You should leave aside your feelings and analyse the problem from every angle possible. In the end, you should aim to make your decision based on the available evidence, not assumptions or bias.

4. Be careful about confirmation bias

It is in our nature to want to confirm our existing ideas rather than challenge them. You should try your best to strive for objectivity while evaluating information.

Often, you may find yourself reading articles that support your ideas, but why not broaden your horizons by learning about the other viewpoint?

By doing so, you will have the opportunity to get closer to the truth and may even find unexpected support and evidence for your conclusion.

Curiosity will keep you on the right path. However, if you find yourself searching for information or confirmation that aligns only with your opinion, then it’s important to take a step back. Take a short break, acknowledge your bias, clear your mind and start researching all over.

5. Synthesis

As we have already mentioned a couple of times, medical students are preoccupied with their studies. Therefore, you have to learn how to synthesise information. This is where you take information from multiple sources and bring the information together. Learning how to do this effectively will save you time and help you make better decisions faster.

You will have already located and evaluated your sources in the previous steps. You now have to organise the data into a logical argument that backs up your position on the problem under consideration.

6. Make a decision

Once you have gathered and evaluated all the available evidence, your last step is to make a logical and well-reasoned conclusion.

By following this process you will ensure that whatever decision you make can be backed up if challenged

Why is critical thinking so important for medical students?

The first and most important reason for mastering critical thinking is that it will help you to avoid medical and clinical errors during your studies and future medical career.

Another good reason is that you will be able to identify better alternative options for diagnoses and treatments. You will be able to find the best solution for the patient as a whole which may be different to generic advice specific to the disease.

Furthermore, thinking critically as a medical student will boost your confidence and improve your knowledge and understanding of subjects.

In conclusion, critical thinking is a skill that can be learned and improved. It will encourage you to be the best version of yourself and teach you to take responsibility for your actions.

Critical thinking has become an essential for future health care professionals and you will find it an invaluable skill throughout your career.

We’ll keep you updated

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Int J Environ Res Public Health

Communication Skills, Problem-Solving Ability, Understanding of Patients’ Conditions, and Nurse’s Perception of Professionalism among Clinical Nurses: A Structural Equation Model Analysis

This study was intended to confirm the structural relationship between clinical nurse communication skills, problem-solving ability, understanding of patients’ conditions, and nurse’s perception of professionalism. Due to changes in the healthcare environment, it is becoming difficult to meet the needs of patients, and it is becoming very important to improve the ability to perform professional nursing jobs to meet expectations. In this study method, structural model analysis was applied to identify factors influencing the perception of professionalism in nurses. The subjects of this study were 171 nurses working at general hospitals in city of Se, Ga, and Geu. Data analysis included frequency analysis, identification factor analysis, reliability analysis, measurement model analysis, model fit, and intervention effects. In the results of the study, nurse’s perception of professionalism was influenced by factors of communication skills and understanding of the patient’s condition, but not by their ability to solve problems. Understanding of patient’s condition had a mediating effect on communication skills and nursing awareness. Communication skills and understanding of the patient’s condition greatly influenced the nurse’s perception of professionalism. To improve the professionalism of clinical nurses, nursing managers need to emphasize communication skills and understanding of the patient’s condition. The purpose of this study was to provide a rationale for developing a program to improve job skills by strengthening the awareness of professional positions of clinical nurses to develop nursing quality of community.

1. Introduction

Changes in the environment related to climate and pollution are causing health problems and various diseases such as respiratory and circulatory problems, metabolic disorders, and chronic diseases. Moreover, access to modern healthcare facilities has created greater expectations among patients receiving personalized healthcare and high-quality healthcare. As the difficulty of satisfying the demands of patients increases, enhancing nursing capabilities has become increasingly important [ 1 ]. To improve this, hospitals are making efforts to change the internal and external environments so as to increase the number of nurses, reduce the length of hospital stays, and enable efficient nursing practice. Despite these efforts, the workloads of nurses and the demand for clinical nurses are continuously increasing [ 2 , 3 ]. As a result, nurses are developing negative attitudes and prejudices toward patients, as well as negative perceptions of professionalism. To address this, the cultivation and strengthening of nursing professionals’ capabilities is essential.

Nurses’ perception of professionalism is an important element influencing their ability to perform independent nursing, and a good perception of their profession results in a positive approach to solving patients’ problems [ 4 , 5 ]. In addition, the characteristics and abilities of individual nurses can influence the level of care and enable them to understand patients, solve problems, and provide holistic care, which is the ultimate goal of the nursing process [ 6 , 7 ]. Thus, patients expect nurses to not only have medical knowledge of the disease but to also be able to comprehensively assess the patient’s problems and be independent and creative in nursing [ 8 ]. This attitude can have a major impact on the quality of nursing services and can inspire pride in the nursing occupation and professional achievement. These findings can also be used by nurses to prevent burnout and maintain professionalism [ 9 , 10 ].

To respond to the increasing demands for diverse qualitative and quantitative nursing services and to strengthen the capabilities of nursing professionals, efforts have been made to move nursing education toward scientific and creative education. However, in point-of-care environments, not only are nurses prevented from making independent decisions regarding nursing, but also the diverse personal capabilities necessary for such independent behavior are not sufficiently developed [ 11 ]. Therefore, it is important to enhance clinical nurses’ perceptions of the nursing profession; maintain a balance of nursing capabilities; provide novel, high-quality nursing services; and identify assistive nursing education methods and obstructive environmental factors [ 10 ].

Communication skills involve a person’s ability to accurately understand (through both verbal and non-verbal indications) another person, and sufficiently deliver what the person desires [ 12 , 13 ]. Good communication skills are a primary requirement for providing professional nursing services because they enable an in-depth understanding of patients, solving of complicated problems, and reasonable and logical analysis of situations [ 14 , 15 , 16 ]. When effective communication takes place, nurses’ problem-solving abilities and perceived professionalism strengthen [ 17 , 18 ].

According to Park [ 19 ], nurses have difficulties in interpersonal relationships when social tension and interaction skills are low and communication is poor. In addition, these factors are negatively affected not only in the work of the nurse but also in the perception of the profession. Communication skills are associated with both the formation of relationships with patients and the ability to perform holistic nursing [ 20 ]. In order to improve and develop the overall nursing function of a clinical nurse like this, it is important to complement the relevant integrated nursing abilities [ 21 , 22 ].

Previous studies have investigated the importance of communication skills for nurses, and the relationships between nurses’ problem-solving ability and their understanding of the patients’ conditions. Nonetheless, data that can comprehensively explain the structural relationships between these qualities and how they affect the job perception of nurses remains insufficient.

Therefore, the present study aims to identify the structural model for the relationships between nurses’ communication skills, problem-solving ability, understanding of patients’ conditions, and nurse’s perception of professionalism. Additionally, the study provides basic data necessary for developing programs for improving nursing abilities.

The purpose of this study is to construct a theoretical model that explains the structural relationships among nurses’ communication skills, problem-solving ability, understanding of patients’ conditions, and nurse’s perception of professionalism. In addition, the study aimed to verify this model using empirical data.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. study design.

To create and analyze the structural model for clinical nurses’ communication skills, problem-solving ability, understanding of patients’ conditions, and nurse’s perception of professionalism, the theoretical relationships among the variables were developed based on related theories.

In this study, communication skills were set as the exogenous variables, whereas problem-solving ability, understanding of patients’ conditions, and perception of the nursing occupation were set as the endogenous variables. In addition, communication skills were set as the independent variables and nursing job perceptions as the dependent variable. This is because the ability of communication helps to maintain an intimate relationship with the patient and to assess the patient’s condition through each other’s relationship and to solve problems and develop correct understanding. Communication skills, problem-solving ability, and understanding of patients’ conditions were set as the parameters for determining causality. The research model is shown in Figure 1 .

Study model.

2.2. Study Participants

The structural equation model has less than 12 measurement variables. The sample size usually requires 200 to 400 participants [ 23 ]. A total of 250 participants were selected for the study. In line with ethical standards and practices, participants received a full explanation on the purpose of the study. They were briefed that the information collected would be used for research purposes only. Furthermore, they were informed that they could withdraw from the study at any time.

2.3. Data Collection Method

Data collection for this study was performed by two researchers unrelated to the hospital from April 20 to May 1, 2019. A questionnaire was used to collect data from clinical nurses working in five hospitals in Seoul, Gyeonggi, and Gangwon provinces. Of the 250 questionnaires disseminated, we received 225 completed returns. However, 54 were considered inaccurate, inconsistent, or unsatisfactory for coding purposes. Thus, 171 fully completed valid questionnaires comprised the final dataset for analysis.

2.4. Research Instruments

2.4.1. communication skills.

In this study, the communication skill instrument developed by Lee and Jang [ 24 ] was used. Its contents were modified and supplemented to clearly understand the communication skills of nurses. Our questionnaire comprised 20 questions with five questions each concerning “interpretation ability,” “self-reveal,” “leading communication,” and “understanding others’ perspectives.” The answers were rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 0 = “strongly disagree” to 4 = “strongly agree.” For this study, the Cronbach’s alpha value was 0.81.

2.4.2. Problem-Solving Ability

The tool developed by Lee [ 25 ] was used to measure the problem-solving ability of clinical nurses. The survey comprised 25 questions, with five questions each concerning “problem recognition,” “information-gathering,” “divergent thinking,” “planning power,” and “evaluation.” Items were scored on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 0 = “strongly disagree” to 4 = “strongly agree.” The internal consistency confidence value Cronbach’s alpha was 0.79.

2.4.3. Understanding Patients’ Condition

To measure nurses’ understanding of patients’ conditions, we developed 10 questions by revising and supplementing items from an existing understanding-measurement tool [ 26 ]. With a total of ten questions, we measured “diagnostic name,” “patient-treatment planning,” and “nursing intervention processes.” Items were scored using a five-point Likert scale ranging from 0 = “strongly disagree” to 4 = “strongly agree.” The internal consistency confidence value Cronbach’s alpha was 0.81.

2.4.4. Nurse’s Perception of Professionalism

Nurse’s perception of professionalism was measured using a tool developed by revising the 25 questions created by Kang et al. [ 1 ]. With a total of ten questions, we measured “vocation” and “autonomy.” Items were scored using a five-point Likert scale. The internal consistency confidence value Cronbach’s alpha was 0.81.

2.5. Data Analysis

To identify the relationships among the set variables, the data were computed statistically using the program included in IBM SPSS 24.0 and AMOS 23.0. (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The analysis methods were as follows:

- Frequency analysis was conducted to identify the subjects’ demographic and general characteristics.

- The reliability of the questionnaire was verified using Cronbach’s α coefficients.

- Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed to verify the convergent validity of the selected measurement tool.