An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Treatment of Anorexia Nervosa-New Evidence-Based Guidelines

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Psychosomatic Medicine and Psychotherapy, University Hospital Tuebingen, Osianderstr. 5, 72076 Tuebingen, Baden-Wuerttemberg, Germany. [email protected].

- 2 Department of Psychosomatic Medicine and Psychotherapy, LWL University Hospital, Ruhr-University Bochum, Alexandrinenstr. 1-3, Nordrhein-Westfalen, 55791 Bochum, Germany. [email protected].

- 3 Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Psychosomatics and Psychotherapy, University Hospital of the RWTH Aachen, Neuenhofer Weg 21, Nordrhein-Westfalen, 52074 Aachen, Germany. [email protected].

- 4 Department of Psychosomatic Medicine and Psychotherapy, University Hospital Freiburg, Hauptstr. 8, Baden-Wuerttemberg, 79104 Freiburg, Germany. [email protected].

- PMID: 30700054

- PMCID: PMC6406277

- DOI: 10.3390/jcm8020153

Anorexia nervosa is the most severe eating disorder; it has a protracted course of illness and the highest mortality rate among all psychiatric illnesses. It is characterised by a restriction of energy intake followed by substantial weight loss, which can culminate in cachexia and related medical consequences. Anorexia nervosa is associated with high personal and economic costs for sufferers, their relatives and society. Evidence-based practice guidelines aim to support all groups involved in the care of patients with anorexia nervosa by providing them with scientifically sound recommendations regarding diagnosis and treatment. The German S3-guideline for eating disorders has been recently revised. In this paper, the new guideline is presented and changes, in comparison with the original guideline published in 2011, are discussed. Further, the German guideline is compared to current international evidence-based guidelines for eating disorders. Many of the treatment recommendations made in the revised German guideline are consistent with existing international treatment guidelines. Although the available evidence has significantly improved in quality and amount since the original German guideline publication in 2011, further research investigating eating disorders in general, and specifically anorexia nervosa, is still needed.

Keywords: anorexia nervosa; evidenced-based; guidelines; treatment.

PubMed Disclaimer

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Similar articles

- The diagnosis and treatment of eating disorders. Herpertz S, Hagenah U, Vocks S, von Wietersheim J, Cuntz U, Zeeck A; German Society of Psychosomatic Medicine and Psychotherapy; German College for Psychosomatic Medicine. Herpertz S, et al. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2011 Oct;108(40):678-85. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2011.0678. Epub 2011 Oct 7. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2011. PMID: 22114627 Free PMC article.

- A novel outpatient treatment model for patients with severe and enduring anorexia nervosa: an observational study of patient characteristics, treatment goals, and treatment course. Ålgars M, Oshukova S, Suokas J. Ålgars M, et al. J Eat Disord. 2023 Sep 6;11(1):150. doi: 10.1186/s40337-023-00877-x. J Eat Disord. 2023. PMID: 37674214 Free PMC article.

- Inpatient versus outpatient care, partial hospitalisation and waiting list for people with eating disorders. Hay PJ, Touyz S, Claudino AM, Lujic S, Smith CA, Madden S. Hay PJ, et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019 Jan 21;1(1):CD010827. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010827.pub2. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019. PMID: 30663033 Free PMC article.

- Medical instability in typical and atypical adolescent anorexia nervosa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brennan C, Illingworth S, Cini E, Bhakta D. Brennan C, et al. J Eat Disord. 2023 Apr 6;11(1):58. doi: 10.1186/s40337-023-00779-y. J Eat Disord. 2023. PMID: 37024943 Free PMC article. Review.

- Energy expenditure during nutritional rehabilitation: a scoping review to investigate hypermetabolism in individuals with anorexia nervosa. Reed KK, Silverman AE, Abbaspour A, Burger KS, Bulik CM, Carroll IM. Reed KK, et al. J Eat Disord. 2024 May 21;12(1):63. doi: 10.1186/s40337-024-01019-7. J Eat Disord. 2024. PMID: 38773635 Free PMC article. Review.

- Pediatric early-phase anorexia nervosa without hypokalemia exhibiting acute tubular injury: a case report. Ohne M, Watanabe Y, Oyake C, Onuki Y, Watanabe T, Ikeda H. Ohne M, et al. CEN Case Rep. 2024 Apr 24. doi: 10.1007/s13730-024-00878-y. Online ahead of print. CEN Case Rep. 2024. PMID: 38658457

- Choosing Appropriate Nutritional Therapy for Patients With Anorexia Nervosa Exhibiting Liver Dysfunction: A Case Report. Tsutsumi M, Okamoto N, Tesen H, Kijima R, Yoshimura R. Tsutsumi M, et al. Cureus. 2024 Feb 16;16(2):e54332. doi: 10.7759/cureus.54332. eCollection 2024 Feb. Cureus. 2024. PMID: 38500915 Free PMC article.

- "Maze Out": a study protocol for a randomised controlled trial using a mix methods approach exploring the potential and examining the effectiveness of a serious game in the treatment of eating disorders. Guala MM, Bikic A, Bul K, Clinton D, Mejdal A, Nielsen HN, Stenager E, Søgaard Nielsen A. Guala MM, et al. J Eat Disord. 2024 Mar 1;12(1):35. doi: 10.1186/s40337-024-00985-2. J Eat Disord. 2024. PMID: 38429839 Free PMC article.

- The Impact of Clinical Factors, Vitamin B12 and Total Cholesterol on Severity of Anorexia Nervosa: A Multicentric Cross-Sectional Study. Affaticati LM, Buoli M, Vaccaro N, Manzo F, Scalia A, Coloccini S, Zuliani T, La Tegola D, Capuzzi E, Nicastro M, Colmegna F, Clerici M, Dakanalis A, Caldiroli A. Affaticati LM, et al. Nutrients. 2023 Nov 29;15(23):4954. doi: 10.3390/nu15234954. Nutrients. 2023. PMID: 38068810 Free PMC article.

- Case report: Rapid improvements of anorexia nervosa and probable myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome upon metreleptin treatment during two dosing episodes. Hebebrand J, Antel J, von Piechowski L, Kiewert C, Stüve B, Gradl-Dietsch G. Hebebrand J, et al. Front Psychiatry. 2023 Nov 9;14:1267495. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1267495. eCollection 2023. Front Psychiatry. 2023. PMID: 38025476 Free PMC article.

- Teufel M., Friederich H.-C., Groß G., Schauenburg H., Herzog W., Zipfel S. Anorexia nervosa – Diagnostik und Therapie. PPmP. 2009;59:454–466. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1223371. - DOI - PubMed

- Treasure J., Zipfel S., Micali N., Wade T., Stice E., Claudino A., Schmidt U., Frank G.K., Bulik C.M., Wentz E. Anorexia nervosa. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 2015;1:15074. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2015.74. - DOI - PubMed

- Zipfel S., Löwe B., Reas D.L., Deter H.C., Herzog W. Long-term prognosis in anorexia nervosa: Lessons from a 21-year follow-up study. Lancet. 2000;355:721–722. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)05363-5. - DOI - PubMed

- Zipfel S., Giel K.E., Bulik C.M., Hay P., Schmidt U. Anorexia nervosa: Aetiology, assessment, and treatment. Lancet Psychiat. 2015;2:1099–1111. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00356-9. - DOI - PubMed

- World Health Organization (WHO) ICD 11 International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision. [(accessed on 17 December 2018)]; Available online: https://icd.who.int/

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

Related information

- Cited in Books

Grants and funding

- N/A/Christina Barz-Stiftung, Association of German Academic Foundations

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources.

- Europe PubMed Central

- PubMed Central

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

- DOI: 10.1038/nrdp.2015.74

- Corpus ID: 21580134

Anorexia nervosa

- J. Treasure , Stephan Zipfel , +7 authors Elisabet Wentz

- Published in Nature Reviews Disease… 2015

- Medicine, Psychology

153 Citations

Anorexia nervosa: outpatient treatment and medical management, sudden gains in the outpatient treatment of anorexia nervosa: a process‐outcome study, anorexia nervosa in adolescents., treatment of anorexia nervosa—new evidence-based guidelines, body shape in inpatients with severe anorexia nervosa, emerging therapeutic targets for anorexia nervosa, when anorexia nervosa symptoms mask kallmann syndrome.

- Highly Influenced

- 10 Excerpts

Anorexia nervosa: 30-year outcome

Trauma experiences are common in anorexia nervosa and related to eating disorder pathology but do not influence weight-gain during the start of treatment, pseudo bartter syndrome in anorexia nervosa, 227 references, antidepressants for anorexia nervosa., inpatient treatment for anorexia nervosa: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials, long-term follow-up of adolescent onset anorexia nervosa in northern sweden, epidemiology and course of anorexia nervosa in the community., anorexia nervosa in young men: a cohort study., compulsivity in anorexia nervosa: a transdiagnostic concept, should amenorrhea be a diagnostic criterion for anorexia nervosa, temperament-based treatment for anorexia nervosa., anorexia nervosa: outcome and prognostic factors after 20 years, adolescent-onset anorexia nervosa: 18-year outcome., related papers.

Showing 1 through 3 of 0 Related Papers

JavaScript disabled

You have to enable JavaScript in your browser's settings in order to use the eReader.

Or try downloading the content offline

Did you know?

Reader environment loaded

Loading publication (1.4 MB)

Large documents might take a while

MINI REVIEW article

Bulimia nervosa and treatment-related disparities: a review.

- College of Health Sciences, Utah Tech University, St. George, UT, United States

Introduction: Bulimia nervosa (BN) is a type of eating disorder disease usually manifesting between adolescence and early adulthood with 12 as median age of onset. BN is characterized by individuals’ episodes of excessive eating of food followed by engaging in unusual compensatory behaviors to control weight gain in BN. Approximately 94% of those with BN never seek or delay treatment. While there are available treatments, some populations do not have access. Left untreated, BN can become severe and lead to other serious comorbidities. This study is a review of randomized controlled trials to explore available treatments and related treatment disparities. The objective of this review was to identify differences among treatment modalities of BN and aide in the further treatment and research of bulimia nervosa.

Methods: This study followed narrative overview guidelines to review BN treatment studies published between 2010 and 2021. The authors used PubMed and PsychInfo databases to search for articles meeting the inclusion criteria. Search terms included phrases such as, BN treatment, BN and clinical trials, and BN and randomized clinical trials.

Results: Most of the reviewed studies had their sample sizes between 80 and 100% female with age range between 18 and 60 years old. Sample sizes were mostly between 80 and 100% white. Treatment practices included both pharmacological and psychosocial interventions, such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and limited motivational interviewing (MI). Most studies were in outpatient settings.

Conclusion: Reviewed research shows that certain populations face disparities in BN treatment. Generally, individuals older than 60, males and racial minorities are excluded from research. Researchers and practitioners need to include these vulnerable groups to improve BN treatment-related disparities.

Bulimia nervosa (BN) is a serious eating disorder (ED) that usually manifests between adolescence and early adulthood ( Hail and Le Grange, 2018 ). BN is characterized by episodes of recurrent binge eating ( Martins et al., 2020 ). BN involves engaging in compensatory behaviors such as self-induced vomiting, misuse of laxatives, diuretics, or enemas ( Mond, 2013 ; American Psychiatric Association, 2022 ). Other compensatory behaviors may include activities such as fasting or excessive exercise ( Mond, 2013 ; American Psychiatric Association, 2022 ). The episodes can be mixed and are classified as recurrent episodes of binge eating in any 2-h period that is larger than most people would during a similar period ( Mond, 2013 ; American Psychiatric Association, 2022 ). Individuals might go as far as to arrange their schedules to accommodate episodes of bingeing ( Harrington et al., 2015 ).

The median age of onset is 12.4 ( Hail and Le Grange, 2018 ), however onset could be as high as 18–44 years old with a lifetime prevalence of 1.5% among females, and 0.5% among males ( Udo and Grilo, 2018 ). Other research has shown the range of lifetime prevalence among females to be 0.3–4.6% and 0.1–1.3% among males ( van Eeden et al., 2021 ). Research also shows that 85–94% of those with BN never seek professional help, or delay treatment by 4–5 years ( Mathisen et al., 2017 ). Left untreated, BN can become severe and lead to other comorbidities or bad health outcomes, including death in some cases ( Hail and Le Grange, 2018 ). This study is a review of randomized controlled trials to explore available treatments and related treatment disparities. While different authors may define health disparities in different ways, our definition is one generally accepted which is that health disparities are differences or gaps in health outcomes, or even healthcare access, and treatment among populations ( Riley, 2012 ; Arcaya et al., 2015 ). These differences are unjust and preventable and can occur between racial groups, social economic status, or gender ( Riley, 2012 ; Arcaya et al., 2015 ). These differences or gaps would not normally occur if the distribution of resources were fair ( Riley, 2012 ; Arcaya et al., 2015 ). Our objective was to identify these differences in the treatment and research of bulimia nervosa among populations. An identification of these differences is key in the successful treatment and research of bulimia nervosa.

The primary diagnostic criterion of BN is stated in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fourth edition, DSM-IV and Fifth edition, DSM-V ( MacDonald et al., 2014 ; Harrington et al., 2015 ; American Psychiatric Association, 2022 ). Individuals with BN are usually of normal height and weight ( Frank, 2012 ), but can also be overweight which makes the diagnosis of BN challenging ( Harrington et al., 2015 ). Also, according to the DSM criteria, BN is characterized by an episode of binge eating by (a) eating in a discrete period, an amount of food that is larger than most individuals would eat in a similar period and under similar circumstances, and lacking control of eating during this episode. (b) recurrent compensatory behaviors that prevent weight gain, (c) at least once per week for 3 months, (d) self-evaluation of body shape and weight is unduly influenced, and (e) this behavior is not that of anorexia nervosa ( Mond, 2013 ; Harrington et al., 2015 ; American Psychiatric Association, 2022 ). The individual is in partial remission if some, but not all criteria have been met for a sustained period of time and will be considered full remission if none of the criteria is met for a sustained period of time ( Harrington et al., 2015 ; American Psychiatric Association, 2022 ). The average frequency of binge eating and purging has decreased from twice per week, per the DSM-IV, to once per week ( Mond, 2013 ; Harrington et al., 2015 ; American Psychiatric Association, 2022 ), which was the increasing prevalence for BN ranging from 4 to 6.7% ( Nitsch et al., 2021 ).

The severity of BN is based upon the frequency of compensatory behaviors and may reflect other symptoms and functional disability and are categorized based upon average episodes of compensatory behaviors per week. These categories include Mild 1–3, Moderate 4–7, Severe 8–13 and Extreme 14+ ( Harrington et al., 2015 ; Nitsch et al., 2021 ; American Psychiatric Association, 2022 ).

Untreated or undertreated BN

Untreated or undertreated BN is associated with several comorbidities. These comorbidities may include psychiatric disorders, hopelessness, shame and impulsivity, which can contribute to non-suicidal self-harm, suicidal ideation and death by suicide ( Nitsch et al., 2021 ). The suicide rates among individuals with BN are high where compared to the general population, they are 8 times more likely to die by suicide ( Preti et al., 2011 ; Cucchi et al., 2016 ; Nitsch et al., 2021 ). The standardized mortality rates among those with BN are elevated at 1.5 to 2.5% ( Arcelus et al., 2011 ; Nitsch et al., 2021 ). This higher mortality rate in BN is due to the medical complications of purging ( Nitsch et al., 2021 ). These purging behaviors and laxative use can cause electrolyte imbalances leading to increased risk of cardiovascular disease, including ischemic heart disease and in some cases resulting in death in females ( Nitsch et al., 2021 ).

Other problems associated with purging include dental erosion and hypertrophy of salivary glands ( Harrington et al., 2015 ; Nitsch et al., 2021 ), trauma to the pharynx, increased risk of aspiration pneumonia, irregular menses due to endocrine system disruption and gastrointestinal problems ( Nitsch et al., 2021 ). The binge eating aspect of BN can also cause gastrointestinal problems such as bloating, dysphagia and acid reflux ( Nitsch et al., 2021 ). Prognosis and recovery are variable and there is an increased risk of relapse with psychological dysfunction and body image disturbance. There is evidence to support changes in neuronal activity and suggest a link in BN with body image distortion ( Wang et al., 2019 ). Poor outcomes can be attributed to fewer follow-up years, increased drive for thinness and beginning treatment at an older age ( Nitsch et al., 2021 ). It is however estimated that with proper treatment 80% of individuals with BN achieve remission ( Harrington et al., 2015 ).

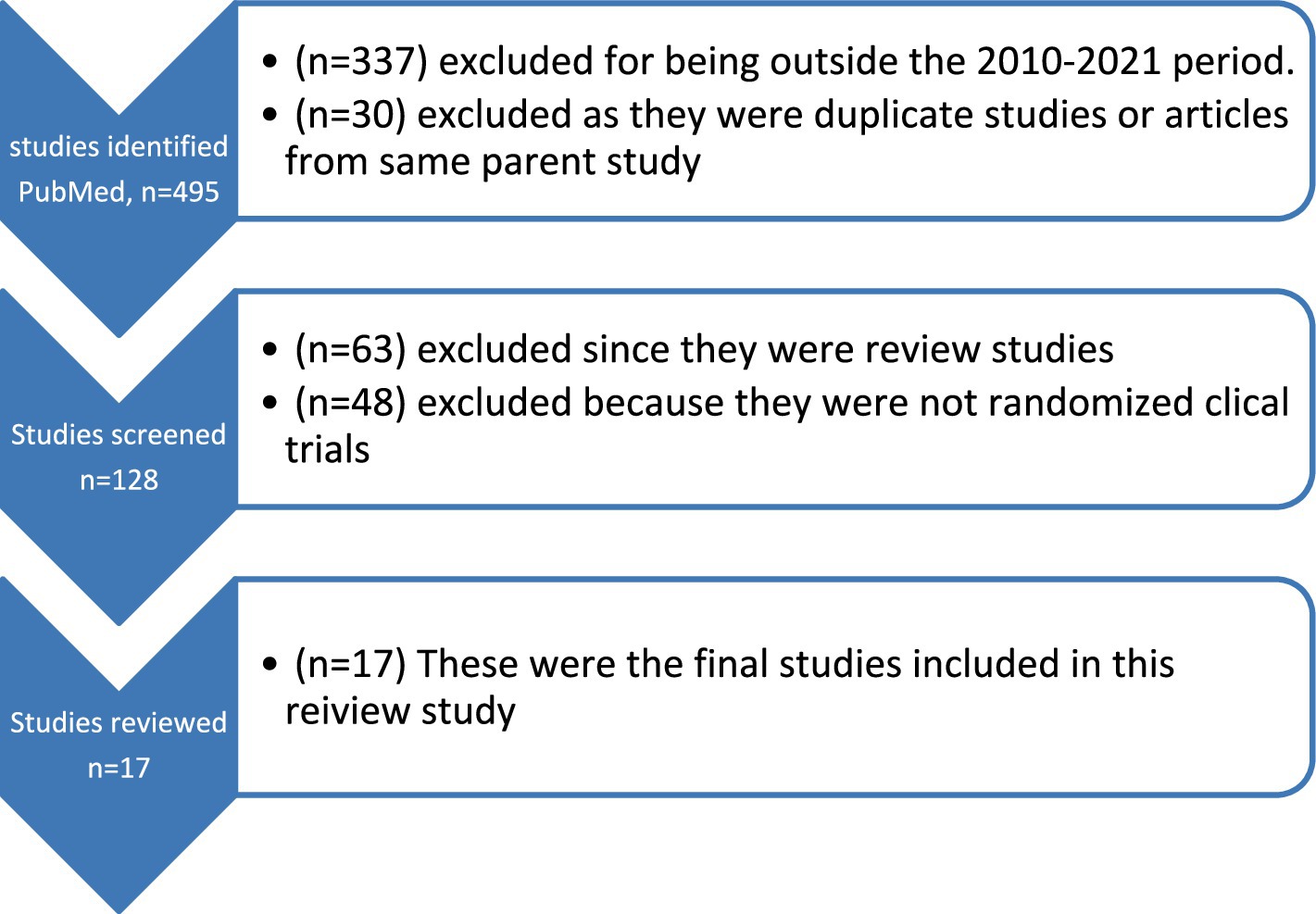

This study followed narrative overview guidelines to review randomized controlled trial ( Wonderlich et al., 2014 ; Jacobi et al., 2017 ; Mannan et al., 2021 ) studies published between 2010 and 2021. The authors searched PubMed and PsychInfo databases to search for articles meeting the inclusion criteria. Search terms included phrases such as bulimia nervosa treatment, bulimia nervosa and clinical trials, bulimia nervosa and randomized clinical trials, or bulimia nervosa diagnosis and treatment. Any studies that did not involve randomized controlled trials and treatment of bulimia nervosa were excluded. Review studies such as systematic reviews or meta-analysis were also excluded from review for this study. This paper was not a review of review studies and because such review works had already been completed by other investigators, they were left out of this current review study. Of the 685 studies resulting from the search terms used, 17 studies met the inclusion our inclusion criteria and were reviewed for this study. The variables examined included, sample size, sex, mean age, race/ethnicity, study setting (inpatient/outpatient), intervention/treatment type, and response to interventions ( Figure 1 ).

Figure 1 . Flow chart of studies reviewed.

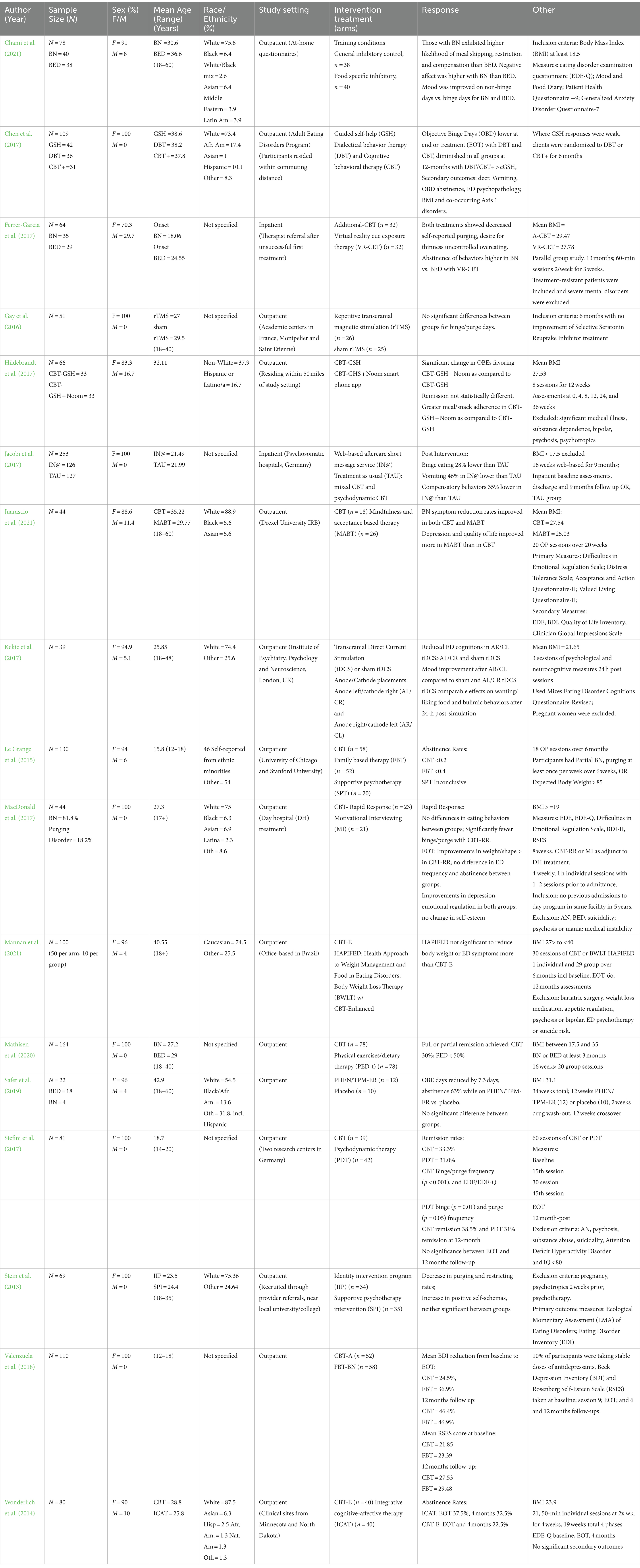

Table 1 (Summary of Bulimia Nervosa Randomized Clinical Trials) is a summary of journal articles published between 2010 and 2021 which were reviewed for this study. Following the inclusion criteria, 17 studies were included in this review. Most of the reviewed studies had their sample sizes between 80 and 100% female with age range between 18 and 60 years old. Sample sizes were mostly between 80 and 100% white. Treatment practices included both pharmacological, and behavioral, or psychosocial interventions, such as cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) and limited motivational interviewing (MI), using at-home questionnaires. Most psychosocial interventions used were CBT and incorporated other strategies such as dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT), family-based therapy (FBT), limited MI, guided self-help (GSH), integrative cognitive-affective therapy (ICAT), virtual reality (VR), mindfulness and acceptance-based therapy (MABT), psychodynamic therapy (PDT), identity intervention program (IIP) and supportive psychotherapy (SPT). Other studies included those utilizing physical exercises and dietary therapy (PED-t), transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), direct current stimulation (DCS), and pharmacological treatments using phentermine/topiramate (PHEN/TPM-ER). Most of the studies were done in outpatient settings.

Table 1 . Summary of bulimia nervosa randomized controlled trial intervention studies (2010–2021).

Our findings show that several behavioral interventions are used for the treatment of BN, with CBT as the preferred choice ( Mathisen et al., 2017 ; Burmester et al., 2021 ). Other behavioral interventions included VR, DBT and FBT. Most individuals with BN do not seek treatment and instead present for weight loss issues, making CBT the first line of defense for treating eating disorders (ED) ( Donnelly et al., 2018 ). Other tools such as the Stroop Test guide clinicians in the understanding of the effects of visual stimuli as it translates into emotional, psychological and neural responses in those with ED and therefore aides in forming clinical treatment programs using CBT and visual imagery ( Burmester et al., 2021 ). The vicious cycle of compensatory strategies that affect perceptions of weight and shape can render CBT effective in treating BN.

The focus of CBT-BN can restructure the cognitive distortions of body shape and weight, perfectionism, low self-esteem, interpersonal stress, and mood tolerance. While self-reporting can be a source of shame, it is important in the problem-solving process during CBT-BN treatment ( Hagan and Walsh, 2021 ). However, FBT is shown to be more effective in adolescents than in adults ( Gorrell et al., 2019 ). Physical exercise can also be used to treat BN symptoms, however, it is not typically used in clinics due to the propensity for those with ED to overexercise and the clinicians’ fear that such exercise prescription would increase the compensatory behaviors ( Bratland-Sanda et al., 2009 ; Quesnel et al., 2018 ; Mathisen et al., 2020 ). A combination of Dietary Therapy and Physical Exercise (PED-t) was studied as a trial, as a new method of treatment and was hypothesized to re-establish healthy patterns by focusing on the functionality of the body rather than appearance. This also aimed to provide knowledge to those suffering with ED, specifically BN and binge eating disorder to change thought patterns. The concern for this treatment approach was the overall long-term effectiveness yet is still an approach that is being considered as part of their evidenced-based practice ( Mathisen et al., 2020 ).

CBT and other behavioral interventions compared

Individuals receiving CBT treatment have reported a decreased desire for thinness and demonstrated fewer purging episodes ( Ferrer-García et al., 2017 ). Studies also compared CBT with other methods such as Physical Exercise/Dietary Therapy (PED-t). A comparison of CBT and PED-t found that in addition to reduced depression symptoms, PED-t performed just as good as CBT in reducing the symptoms of BN and binge eating disorder and improving other psychosocial impairment ( Mathisen et al., 2020 ). There were also increased abstinence rates with VR ( Ferrer-García et al., 2017 ), and mindfulness and acceptance-based treatment (MABT) performed just as equal to CBT in increased retention rates and reductions in BN symptoms ( Juarascio et al., 2021 ). Participants receiving Guided Self-Help (GSH) had fewer objective binge eating days (OBD), vomiting, psychopathology and improved abstinence rates ( Chen et al., 2017 ) and greater meal/snack adherence with GSH and CBT combined ( Hildebrandt et al., 2017 ). These results suggest that while CBT is the preferred method, approaches such as PED-t and MABT can be just as good and even good alternatives when use of CBT is not possible ( Mathisen et al., 2020 ; Juarascio et al., 2021 ). Abstinence rates among adolescents aged 12–18 were greater with FBT ( Le Grange et al., 2015 ), and with improved cognitive symptoms, self-esteem and depressive symptoms as compared to CBT and SPT ( Ciao et al., 2015 ). Further research is needed to determine effective treatment outcomes for adolescents.

In addition to CBT, other innovative methods were found in the review. Identity Intervention Program (IIP) was used to identify self-schemas and promote new cognitive structures. Supportive Psychotherapy Intervention (SPI) was used as the control group for this study. Participants used descriptive cards to identify how they think about themselves, along with the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), Psychological Well-Being scales and a Health Survey during this study. At end of treatment, the IIP group had higher mean increases in positive self-schemas, with no significance in the SPT group, taken from baseline measurements ( Stein et al., 2013 ). Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) and sham rTMS were used to determine the efficacy of reducing food cravings in bulimic patients by stimulating the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. This resulted in no significant differences between groups for binge/purge days ( Gay et al., 2016 ). Use of at home questionnaires were used to determine food cravings, binge-eating, negative mood, and meal skipping using general inhibitory control and food specific inhibitory control methods.

Results showed that although negative mood and binge eating co-occurred, there were no significant differences in binge eating days and negative mood between patient groups. Food cravings were also higher on binge days and did not differ between groups ( Chami et al., 2021 ). Other methods to consider are transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS) which has shown comparable effects of wanting and liking food and bulimic behaviors after receiving tDCS treatment vs. sham tDCS. This method utilized two varieties of anode/cathode placement to determine effects on mood, ED cognitions and bulimic behaviors, exhibiting reduced ED cognitions and mood improvement with anode right/cathode left (AR/CL) versus reduced bulimic behaviors with anode left/cathode right (AL/CR) placement ( Kekic et al., 2017 ).

Pharmacological treatment

In cases of comorbidities, pharmacological interventions are used. Over half of those diagnosed with BN meet criteria for having a major depressive episode, and others may also suffer from obsessive compulsive disorder, social phobia, anxiety, or substance use disorders. Other psychological traits could be perfectionism, social withdrawal, emotional dysregulation, and poor distress tolerance ( Harrington et al., 2015 ). Due to the possibility of underlying depression or other comorbidities, use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) may be prescribed for BN to decrease binge and purge frequency especially among those who have not responded initially to psychotherapy ( Harrington et al., 2015 ). Use of Bupropion has been contraindicated due to an increased risk of seizure and has a boxed warning ( Nitsch et al., 2021 ). Use of stimulant medications are often discontinued until individuals have been abstinent of purging behaviors for a period of time ( Nitsch et al., 2021 ). Research shows that among adolescents with BN, 88% meet the criteria for one or more comorbidities for mood and anxiety disorders, and low self-esteem, with depressive disorder being the most common.

Although both CBT and FBT have shown to improve depression and self-esteem for adolescents 12–18, based on the Beck Depression Inventory and Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES), neither treatment is adequate and a supplemental pharmacological intervention is helpful especially among individuals with BN ( Valenzuela et al., 2018 ).

This study identified some treatment-related disparities of individuals with BN. Most of the studies reviewed enrolled participants between age 18 and 60 and therefore creating a gap of limited research on those aged under 12 and over 60 ( Safer et al., 2019 ; Stedal et al., 2023 ). Out of the 17 studies we reviewed, only 3 included participants between ages 12 and 18 ( Le Grange et al., 2015 ; Stefini et al., 2017 ; Valenzuela et al., 2018 ). While the majority onset age is between 18–20 and 30–44, there is evidence that individuals under 18 and over 44 also suffer from BN ( Kotler et al., 2003 ; Silén and Keski-Rahkonen, 2022 ; Cadwallader et al., 2023 ). Along with these age groups, males are often excluded from the research and interventions, yet it is known that males also suffer from BN ( Ferrer-García et al., 2017 ; Hildebrandt et al., 2017 ) and females’ responses to interventions could be different from that of males. Also unknown, and mostly excluded in the literature is how BN affects other marginalized populations such as LGBTQ individuals ( Simone et al., 2020 ). Moreover, many studies also exclude individuals that are not identified as White/Caucasian ( Stein et al., 2013 ; Chami et al., 2021 ; Juarascio et al., 2021 ) and further research is needed for non-English speaking individuals and/or less acculturated minoritized groups. Individuals with serious mental illness and severe substance use are generally excluded from studies. Most of the studies in this review were done in outpatient settings ( Gay et al., 2016 ; Chen et al., 2017 ) leaving few opportunities or none for individuals in inpatient settings to participate in research and newer treatment opportunities. Interventions presented in this review are largely behavioral and research is needed to determine the impact of psychotropics and holistic medicine alone, or in conjunction with behavioral therapies.

Research shows that all in the general population face risks of developing BN and that treatments are available. However, in research reviewed in this study, certain populations such as those of male sex, age group, or racial minority groups are excluded from research and treatment options and therefore creating bulimia nervosa treatment-related disparities. To improve and eliminate the bulimia nervosa treatment disparities, researchers and practitioners need to include marginalized populations such as the LGBTQ or other vulnerable groups such as racial minorities, and all those populations generally left out of research and treatment.

Author contributions

KW: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RK: Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to RK for providing education in research methodology, which inspired me to continue in my research. Also, thank you for your mentorship during this process. I also want to thank Utah Tech University and the University of Utah for providing me with the opportunity to present my poster on bulimia nervosa research.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

American Psychiatric Association (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders . 5th Edn: APA Press.

Google Scholar

Arcaya, M. C., Arcaya, A. L., and Subramanian, S. V. (2015). Inequalities in health: definitions, concepts, and theories. Glob. Health Action united states. 8:27106. doi: 10.3402/gha.v8.27106

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Arcelus, J., Mitchell, A. J., Wales, J., and Nielsen, S. (2011). Mortality rates in patients with anorexia nervosa and other eating disorders. A meta-analysis of 36 studies. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 68, 724–731. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.74

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Bratland-Sanda, S., Rosenvinge, J. H., Vrabel, K. A., Norring, C., Sundgot-Borgen, J., Rø, Ø., et al. (2009). Physical activity in treatment units for eating disorders: clinical practice and attitudes. Eat. Weight Disord. 14, e106–e112. doi: 10.1007/BF03327807

Burmester, V., Graham, E., and Nicholls, D. (2021). Physiological, emotional and neural responses to visual stimuli in eating disorders: a review. J. Eat. Disord. 9:23. doi: 10.1186/s40337-021-00372-1

Cadwallader, J. S., Orri, M., Barry, C., Falissard, B., Hassler, C., and Huas, C. (2023). Description of patients with eating disorders by general practitioners: a cohort study and focus on co-management with depression. J. Eat. Disord. 11:185. doi: 10.1186/s40337-023-00901-0

Chami, R., Reichenberger, J., Cardi, V., Lawrence, N., Treasure, J., and Blechert, J. (2021). Characterising binge eating over the course of a feasibility trial among individuals with binge eating disorder and bulimia nervosa. Appetite 164:105248. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2021.105248

Chen, E. Y., Cacioppo, J., Fettich, K., Gallop, R., Mccloskey, M. S., Olino, T., et al. (2017). An adaptive randomized trial of dialectical behavior therapy and cognitive behavior therapy for binge-eating. Psychol. Med. 47, 703–717. doi: 10.1017/S0033291716002543

Ciao, A. C., Accurso, E. C., Fitzsimmons-Craft, E. E., and Le Grange, D. (2015). Predictors and moderators of psychological changes during the treatment of adolescent bulimia nervosa. Behav. Res. Ther. 69, 48–53. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2015.04.002

Cucchi, A., Ryan, D., Konstantakopoulos, G., Stroumpa, S., Kaçar, A., Renshaw, S., et al. (2016). Lifetime prevalence of non-suicidal self-injury in patients with eating disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol. Med. 46, 1345–1358. doi: 10.1017/S0033291716000027

Donnelly, B., Touyz, S., Hay, P., Burton, A., Russell, J., and Caterson, I. (2018). Neuroimaging in bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder: a systematic review. J. Eat. Disord. 6:3. doi: 10.1186/s40337-018-0187-1

Ferrer-García, M., Gutiérrez-Maldonado, J., Pla-Sanjuanelo, J., Vilalta-Abella, F., Riva, G., Clerici, M., et al. (2017). A randomised controlled comparison of second-level treatment approaches for treatment-resistant adults with bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder: assessing the benefits of virtual reality Cue exposure therapy. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 25, 479–490. doi: 10.1002/erv.2538

Frank, G. K. (2012). Advances in the diagnosis of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa using brain imaging. Expert. Opin. Med. Diagn. 6, 235–244. doi: 10.1517/17530059.2012.673583

Gay, A., Jaussent, I., Sigaud, T., Billard, S., Attal, J., Seneque, M., et al. (2016). A lack of clinical effect of high-frequency rTMS to dorsolateral prefrontal cortex on bulimic symptoms: a randomised, double-blind trial. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 24, 474–481. doi: 10.1002/erv.2475

Gorrell, S., Kinasz, K., Hail, L., Bruett, L., Forsberg, S., Lock, J., et al. (2019). Rituals and preoccupations associated with bulimia nervosa in adolescents: does motivation to change matter? Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 27, 323–328. doi: 10.1002/erv.2664

Hagan, K. E., and Walsh, B. T. (2021). State of the art: the therapeutic approaches to bulimia nervosa. Clin. Ther. 43, 40–49. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2020.10.012

Hail, L., and Le Grange, D. (2018). Bulimia nervosa in adolescents: prevalence and treatment challenges. Adolesc. Health Med. Ther. 9, 11–16. doi: 10.2147/AHMT.S135326

Harrington, B. C., Jimerson, M., Haxton, C., and Jimerson, D. C. (2015). Initial evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Am. Fam. Physician 91, 46–52

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

Hildebrandt, T., Michaelides, A., Mackinnon, D., Greif, R., Debar, L., and Sysko, R. (2017). Randomized controlled trial comparing smartphone assisted versus traditional guided self-help for adults with binge eating. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 50, 1313–1322. doi: 10.1002/eat.22781

Jacobi, C., Beintner, I., Fittig, E., Trockel, M., Braks, K., Schade-Brittinger, C., et al. (2017). Web-Based Aftercare for Women With Bulimia Nervosa Following Inpatient Treatment: Randomized Controlled Efficacy. Trial. J Med Internet Res. 19, e321.

Juarascio, A. S., Parker, M. N., Hunt, R., Murray, H. B., Presseller, E. K., and Manasse, S. M. (2021). Mindfulness and acceptance-based behavioral treatment for bulimia-spectrum disorders: a pilot feasibility randomized trial. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 54, 1270–1277. doi: 10.1002/eat.23512

Kekic, M., Mcclelland, J., Bartholdy, S., Boysen, E., Musiat, P., Dalton, B., et al. (2017). Single-session transcranial direct current stimulation temporarily improves symptoms, mood, and self-regulatory control in bulimia nervosa: a randomised controlled trial. PLoS One 12:e0167606. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0167606

Kotler, L. A., Devlin, M. J., Davies, M., and Walsh, B. T. (2003). An open trial of fluoxetine for adolescents with bulimia nervosa. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 13, 329–335. doi: 10.1089/104454603322572660

Le Grange, D., Lock, J., Agras, W. S., Bryson, S. W., and Jo, B. (2015). Randomized clinical trial of family-based treatment and cognitive-behavioral therapy for adolescent bulimia nervosa. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 54, 886–94.e2.

Macdonald, D. E., Mcfarlane, T. L., and Olmsted, M. P. (2014). "Diagnostic shift" from eating disorder not otherwise specified to bulimia nervosa using Dsm-5 criteria: a clinical comparison with DSM-IV bulimia. Eat. Behav. 15, 60–62. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2013.10.018

Macdonald, D. E., Mcfarlane, T. L., Dionne, M. M., David, L., and Olmsted, M. P. (2017). Rapid response to intensive treatment for bulimia nervosa and purging disorder: A randomized controlled trial of a CBT intervention to facilitate early behavior change. J. Consult. Clin. Psych. 85, 896–908. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000221

Mannan, H., Palavras, M. A., Claudino, A., and Hay, P. (2021). Baseline Predictors of Adherence in a Randomised Controlled Trial of a New Group Psychological Intervention for People with Recurrent Binge Eating Episodes Associated to Overweight or Obesity. Nutrients, 13

Martins, D., Leslie, M., Rodan, S., Zelaya, F., Treasure, J., and Paloyelis, Y. (2020). Investigating resting brain perfusion abnormalities and disease target-engagement by intranasal oxytocin in women with bulimia nervosa and binge-eating disorder and healthy controls. Transl. Psychiatry 10:180. doi: 10.1038/s41398-020-00871-w

Mathisen, T. F., Rosenvinge, J. H., Friborg, O., Vrabel, K., Bratland-Sanda, S., Pettersen, G., et al. (2020). Is physical exercise and dietary therapy a feasible alternative to cognitive behavior therapy in treatment of eating disorders? A randomized controlled trial of two group therapies. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 53, 574–585. doi: 10.1002/eat.23228

Mathisen, T. F., Rosenvinge, J. H., Pettersen, G., Friborg, O., Vrabel, K., Bratland-Sanda, S., et al. (2017). The PED-t trial protocol: the effect of physical exercise -and dietary therapy compared with cognitive behavior therapy in treatment of bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder. BMC Psychiatry 17:180. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1312-4

Mond, J. M. (2013). Classification of bulimic-type eating disorders: from Dsm-iv to Dsm-5. J. Eat. Disord. 1:33. doi: 10.1186/2050-2974-1-33

Nitsch, A., Dlugosz, H., Gibson, D., and Mehler, P. S. (2021). Medical complications of bulimia nervosa. Cleve. Clin. J. Med. 88, 333–343. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.88a.20168

Preti, A., Rocchi, M. B., Sisti, D., Camboni, M. V., and Miotto, P. (2011). A comprehensive meta-analysis of the risk of suicide in eating disorders. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 124, 6–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2010.01641.x

Quesnel, D. A., Libben, M., Oelke, N., Clark, M., Willis-Stewart, S., and Caperchione, C. M. (2018). Is abstinence really the best option? Exploring the role of exercise in the treatment and management of eating disorders. Eat. Disord. 26, 290–310. doi: 10.1080/10640266.2017.1397421

Riley, W. J. (2012). Health disparities: gaps in access, quality and affordability of medical care. Trans. Am. Clin. Climatol. Assoc. 123:167-72; discussion 172-4

Safer, D. L., Adler, S., Dalai, S. S., Bentley, J. P., Toyama, H., Pajarito, S., et al. (2019). A randomized, placebo-controlled crossover trial of phentermine-topiramate Er in patients with binge-eating disorder and bulimia nervosa. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 53, 266–277.

Silén, Y., and Keski-Rahkonen, A. (2022). Worldwide prevalence of DSM-5 eating disorders among young people. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 35, 362–371. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000818

Simone, M., Askew, A., Lust, K., Eisenberg, M. E., and Pisetsky, E. M. (2020). Disparities in self-reported eating disorders and academic impairment in sexual and gender minority college students relative to their heterosexual and cisgender peers. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 53, 513–524. doi: 10.1002/eat.23226

Stedal, K., Funderud, I., Wierenga, C. E., Knatz-Peck, S., and Hill, L. (2023). Acceptability, feasibility and short-term outcomes of temperament based therapy with support (TBT-S): a novel 5-day treatment for eating disorders. J. Eat. Disord. 11:156. doi: 10.1186/s40337-023-00878-w

Stefini, A., Salzer, S., Reich, G., Horn, H., Winkelmann, K., Bents, H., et al. (2017). Cognitive-behavioral and psychodynamic therapy in female adolescents with bulimia nervosa: a randomized controlled trial. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 56, 329–335. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.01.019

Stein, K. F., Corte, C., Chen, D. G., Nuliyalu, U., and Wing, J. (2013). A randomized clinical trial of an identity intervention programme for women with eating disorders. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 21, 130–142. doi: 10.1002/erv.2195

Udo, T., and Grilo, C. M. (2018). Prevalence and correlates of Dsm-5-defined eating disorders in a nationally representative sample of U.S. Adults. Biol. Psychiatry 84, 345–354. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2018.03.014

Valenzuela, F., Lock, J., Le Grange, D., and Bohon, C. (2018). Comorbid depressive symptoms and self-esteem improve after either cognitive-behavioural therapy or family-based treatment for adolescent bulimia nervosa. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 26, 253–258. doi: 10.1002/erv.2582

Van Eeden, A. E., Van Hoeken, D., and Hoek, H. W. (2021). Incidence, prevalence and mortality of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 34, 515–524. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000739

Wang, L., Bi, K., An, J., Li, M., Li, K., Kong, Q. M., et al. (2019). Abnormal structural brain network and hemisphere-specific changes in bulimia nervosa. Transl. Psychiatry 9:206. doi: 10.1038/s41398-019-0543-1

Wonderlich, S. A., Peterson, C. B., Crosby, R. D., Smith, T. L., Klein, M. H., Mitchell, J. E., et al. (2014). A randomized controlled comparison of integrative cognitive-affective therapy (ICAT) and enhanced cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT-E) for bulimia nervosa. Psychol Med 44, 543–53.

Keywords: bulimia nervosa treatment, bulimia nervosa research, bulimia nervosa treatment-related disparities, bulimia nervosa diagnosis and treatment, bulimia nervosa and clinical trials

Citation: Wilson K and Kagabo R (2024) Bulimia nervosa and treatment-related disparities: a review. Front. Psychol . 15:1386347. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1386347

Received: 15 February 2024; Accepted: 25 July 2024; Published: 14 August 2024.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2024 Wilson and Kagabo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kim Wilson, [email protected]

† ORCID: Kim Wilson, orcid.org/0009-0004-4796-2562 Robert Kagabo, orcid.org/0000-0002-9510-7200

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of treated and untreated adults with bulimia nervosa or binge-eating disorder recruited for a large-scale research study

Add to collection, downloadable content.

- Affiliation: College of Arts and Sciences, Department of Psychology and Neuroscience

- Other Affiliation: Department of Biotechnology, Dr D. Y. Patil Biotechnology and Bioinformatics Institute, Pune, India

- Other Affiliation: Department of Psychology, State University of New York at Albany, Albany, NY, USA

- Other Affiliation: Recovery Record, Inc, Palo Alto, CA, USA

- Affiliation: School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry

- Background Eating disorders affect millions of people worldwide, but most never receive treatment. The majority of clinical research on eating disorders has focused on individuals recruited from treatment settings, which may not represent the broader population of people with eating disorders. This study aimed to identify potential differences in the characteristics of individuals with eating disorders based on whether they self-reported accessing treatment or not, in order to contribute to a better understanding of their diverse needs and experiences. Methods The study population included 762 community-recruited individuals (85% female, M±SD age=30±7 years) with bulimia nervosa or binge-eating disorder (BN/BED) enrolled in the Binge Eating Genetics Initiative (BEGIN) United States study arm. Participants completed self-report surveys on demographics, treatment history, past and current eating disorder symptoms, weight history, and their current mental health and gastrointestinal symptoms. Untreated participants (n=291, 38%) were compared with treated participants (n=471, 62%) who self-reported accessing BN/BED treatment at some point in their lives. Results Untreated participants disproportionately self-identified as male and as a racial or ethnic minority compared with treated participants. Treated participants reported a more severe illness history, specifically, an earlier age at onset, more longstanding and frequent eating disorder symptoms over their lifetime, and greater body dissatisfaction and comorbid mental health symptoms (i.e., depression, anxiety, ADHD) at the time of the study. A history of anorexia nervosa was positively associated with treatment engagement. Individuals self-reporting a history of inpatient or residential treatment exhibited the most severe illness history, those with outpatient treatment had a less severe illness history, and untreated individuals had the mildest illness history. Conclusions Historically overlooked and marginalized populations self-reported lower treatment access rates, while those who accessed treatment reported more severe eating disorder and comorbid mental health symptoms, which may have motivated them to seek treatment. Clinic-based recruitment samples may not represent individuals with milder symptoms or racial and ethnic diversity, and males. Community-based recruitment is crucial for improving the ability to apply research findings to broader populations and reducing disparities in medical research.Trial Registration ClinicalTrials.gov NCT04162574 ( https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04162574 ).

- https://doi.org/10.17615/ah70-je12

- https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-023-00846-4

- In Copyright

- Attribution 4.0 International

- Journal of Eating Disorders

- National Institute of Mental Health

- Brain & Behavior Research Foundation

- Karolinska Institutet

- Directorate for STEM Education

- Springer Nature

This work has no parents.

| Thumbnail | Title | Date Uploaded | Visibility | Actions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2024-08-13 | Public |

Select type of work

Master's papers.

Deposit your masters paper, project or other capstone work. Theses will be sent to the CDR automatically via ProQuest and do not need to be deposited.

Scholarly Articles and Book Chapters

Deposit a peer-reviewed article or book chapter. If you would like to deposit a poster, presentation, conference paper or white paper, use the “Scholarly Works” deposit form.

Undergraduate Honors Theses

Deposit your senior honors thesis.

Scholarly Journal, Newsletter or Book

Deposit a complete issue of a scholarly journal, newsletter or book. If you would like to deposit an article or book chapter, use the “Scholarly Articles and Book Chapters” deposit option.

Deposit your dataset. Datasets may be associated with an article or deposited separately.

Deposit your 3D objects, audio, images or video.

Poster, Presentation, Protocol or Paper

Deposit scholarly works such as posters, presentations, research protocols, conference papers or white papers. If you would like to deposit a peer-reviewed article or book chapter, use the “Scholarly Articles and Book Chapters” deposit option.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.334(7599); 2007 Apr 28

Anorexia nervosa

Jane morris.

Royal Edinburgh Hospital, Edinburgh EH10 5HF

Sara Twaddle

Anorexia nervosa has the highest mortality of any psychiatric disorder. 1 It has a prevalence of about 0.3% in young women. It is more than twice as common in teenage girls, with an average age of onset of 15 years; 80-90% of patients with anorexia are female. Anorexia is the most common cause of weight loss in young women and of admission to child and adolescent hospital services. Most primary care practitioners encounter few cases of severe anorexia nervosa, but these cause immense distress and frustration in carers and professionals. We describe the clinical features of anorexia nervosa and review the current evidence on treatment and management management .

Nineteenth century drawing of young woman with anorexia nervosa

How good is the evidence for managing anorexia nervosa?

Ironically, this most lethal of psychiatric disorders is the Cinderella of research. It is hard to engage patients with anorexia for treatment, let alone research. Furthermore, the complexity of coordinated approaches used in most specialist centres may overwhelm conventional research methods.

High quality evidence on the effects of starvation on the body is available to guide physical aspects of care. 2 Genetic studies, including twin and family studies, 3 and more recently gene analysis, have shed some light on causes, but few randomised controlled trials of treatment exist. In contrast, many randomised controlled trials are found on the management of normal weight bulimia nervosa. 4 Unfortunately, these interventions have a poor response in anorexia nervosa.

This review is based on searches in PubMed, Medline, and PsycLIT for treatment of anorexia nervosa and related eating disorders, and the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) clinical guideline. 5 We found no category A evidence (at least one randomised controlled trial as part of a high quality and consistent body of literature (evidence level 1)), and only family interventions met category B criteria (well conducted clinical studies but no randomised controlled trials (evidence levels 2 and 3) or extrapolated from level I evidence). NICE uses category C recommendations (expert committee reports or clinical experience of respected authorities (evidence level 4) or extrapolation from level 2 or 3) to provide guidance where high quality formal evidence is absent.

Two Cochrane reviews cover antidepressant treatment for anorexia nervosa 6 and individual psychotherapy for adults with the disorder. 7 The reviews are based on only seven and six small studies, respectively, all of which had major methodological limitations. A further electronic and hand search of papers published more recently is supplemented by work in press, conference presentations, and some personal communications with the relatively small group of international experts in the field.

What are the hallmarks of anorexia nervosa?

The core psychological feature of anorexia nervosa is the extreme overvaluation of shape and weight. People with anorexia also have the physical capacity to tolerate extreme self imposed weight loss. Food restriction is only one aspect of the practices used to lose weight. Many people with anorexia use overexercise and overactivity to burn calories. They often choose to stand rather than sit; generate opportunities to be physically active; and are drawn to sport, athletics, and dance. Purging practices include self induced vomiting, together with misuse of laxatives, diuretics, and “slimming medicines.” Patients may also practise “body checking,” which involves repeated weighing, measuring, mirror gazing, and other obsessive behaviour to reassure themselves that they are still thin (box 1).

Box 1 ICD-10 (international classification of diseases, 10th revision) criteria for anorexia nervosa 8

- All five criteria must be met for a definite diagnosis to be made

- Body weight is maintained at least 15% below that expected (either lost or never achieved) or body-mass index is 17.5 or less. Prepubertal patients may fail to gain the expected amount of weight during the prepubertal growth spurt

- Weight loss is self induced by avoiding “fattening foods” together with self induced vomiting, purging, excessive exercising, or using appetite suppressants or diuretics (or both)

- Body image is distorted in the form of a specific psychopathology whereby a dread of fatness persists as an intrusive, overvalued idea and the patient imposes a low weight threshold on himself or herself

- A widespread endocrine disorder involving the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis is manifest in women as amenorrhoea and in men as a loss of sexual interest and potency (except for the persistence of vaginal bleeds in women who are taking replacement hormonal therapy, usually the contraceptive pill). Concentrations of growth hormone and cortisol may be raised, and changes in the peripheral metabolism of thyroid hormone and abnormalities of insulin secretion may also be seen

- If onset is before puberty, the sequence of pubertal events will be delayed or even arrested (growth will cease; in girls the breasts will not develop and primary amenorrhoea will be present; in boys the genitals will remain juvenile). After recovery, puberty will often complete normally, but the menarche will be late

What causes anorexia nervosa?

Anorexia has no single cause. it seems that a genetic predisposition is necessary but not sufficient for development of the disorder. Twin and family studies, 3 brain scans of affected and unaffected family members, and a current multicentre gene analysis support observations that anorexia is found in families with obsessive, perfectionist, and competitive traits, and possibly also autistic spectrum traits.

Anorexia nervosa is precipitated as a coping mechanism against, for instance, developmental challenges, transitions, family conflicts, and academic pressures. Sexual abuse may precipitate anorexia but not more commonly than it would trigger other psychiatric disorders. The onset of puberty and adolescence are particularly common precipitants, but anorexia is also found without apparent precipitants in otherwise well functioning families.

How is anorexia nervosa diagnosed and assessed?

The diagnosis is usually suspected by family, friends, and in younger patients school before a doctor becomes involved. When weight loss is well concealed, presenting features may include depression, obsessive behaviour, infertility, or amenorrhoea. Alternatively, weight loss may be thought to be secondary to allergies or other physical conditions.

A positive diagnosis of psychologically driven weight loss can be made in most patients, without the need for a battery of complex investigations to reach a diagnosis of exclusion. Basic medical investigations, blood tests, electrocardiography, weighing, and measuring the patient provide an opportunity for the patient to return (to discuss the results) and can uncover psychological problems.

If the patient refuses to be weighed it is worth persisting gently and exploring their fears. Doctors should not collude with the illness, but should advise against harmful behaviours such as running marathons, skiing, or undergoing in vitro fertilisation when at low weight.

It falls to primary care to recognise and manage relapses as well as first episodes of the illness, and to support patients and families in appropriate use of services. General practitioners may need support from a specialist in eating disorders, and early referral for more detailed assessment and advice gives patients the message that their illness is of genuine concern.

Summary points

- Anorexia nervosa has the highest rate of mortality of any psychiatric disorder

- It is best to make a positive diagnosis of psychologically driven weight loss, rather than reach a diagnosis by exclusion

- Short term structured treatments—such as cognitive behaviour therapy—are not effective, and longer term therapies that incorporate motivational enhancement techniques are recommended

- Focused family work is effective in adolescents and young adults; counselling can involve the family as a whole or the patient and their family can be treated separately

- To date, no effective drugs are available to treat anorexia

How is serious physical risk managed?

The level of physical risk should be assessed at diagnosis. No safe cut off weight or body mass index exists. Survival analyses show that death is unusual where low weight is maintained purely by starvation. 9 Death is more likely if the patient's weight fluctuates rapidly than if it is stable, even if the body mass index is below 12. Risk is also increased if the patient frequently purges or misuses substances.

Compulsory treatment for anorexia nervosa is clearly indicated by mental health legislation in acute emergencies where the patient is unable to accept treatment. 10 In most countries this means detention in hospital. Legal responsibility becomes less clear once the immediate danger of death or irreversible deterioration has passed. Many centres invoke longer detention orders to continue compulsory refeeding to a healthier weight. Without this, the risk of repeated cycles of detention and relapse exists. In practice, patients in extremis can often be treated with their consent. Voluntary treatment is more likely when the clinician is experienced at managing anorexia and can confidently assess and tolerate fairly high levels of risk in the interests of collaborative therapeutic relationships, rather than coerce patients. Even legal measures of compulsion may be used in a helpful therapeutic way, though, and should not be avoided at all costs.

The best place to admit patients with life threatening anorexia is not always obvious. An acute medical ward—especially one that specialises in endocrinology, gastroenterology, or diabetes—is usually better than a general psychiatric ward. Some non-specialist medical wards have nurse specialists, who are experienced in managing patients with eating disorders. These nurses can help translate recommendations into practice and “troubleshoot” for the furtive compulsions of anorexia.

What is the currently accepted best management?

Anorexia takes an average of five or six years from diagnosis to recovery. Up to 30% of patients do not recover. 11 12 This makes meaningful follow-up of interventions crucial but difficult. Coercive approaches may result in impressive short term weight gain but make patients more likely to identify with and cling on to the behaviour associated with anorexia.

Overall prognosis for patients with eating disorders is independent of whether treatment is received or not. 13 Discredited behavioural regimens for anorexia involved incarceration in hospital, with removal of all “privileges” (visitors, television, independent use of bathroom), which were given back as a reward for weight gain.

Hospital admission is still strongly correlated with poor outcome. 14 Long term prognosis is worse for patients compulsorily detained in an inpatient facility than for those treated voluntarily in the same unit, with more deaths in the first group. 10 The use of brief hospital admissions to acute medical wards at times of life threatening crisis or after overdose may be associated with lower mortality. 9 12

How is weight gain achieved?

In countries where all treatment is given in hospital, refeeding is an early intervention. Subsequent treatment helps patients tolerate, maintain, or regain normal weight. This may also be the preferred approach for children and young adolescents, where long periods at low weight are detrimental to growth and development. Hospital refeeding needs physiological fine tuning and may expose the patient to iatrogenic complications such as infections, the sequelae of passing tubes, and the effects of being exposed to a “proanorexia” culture (by mixing with other patients who have anorexia).

A second approach temporarily accepts low weight, if weight is stable and regularly monitored, while patients or their families take responsibility for refeeding. It is helpful to provide dietetic expertise separately from psychotherapy. One study found that unsupported dietetic advice without parallel interventions had a 100% dropout rate. 15 Weight gain is slower with this second approach, but it is more likely to be maintained. This approach avoids many iatrogenic risks. However, clinicians still need access to medical wards for physical emergencies.

What is the role of psychotherapy?

Short term structured treatments such as cognitive behaviour therapy and interpersonal psychotherapy, which are effective in other eating disorders, have not helped so far in patients with anorexia. One report found no difference in outcome between behaviour therapy and cognitive therapy. 16 The preliminary results of a New Zealand study of cognitive behaviour therapy and interpersonal psychotherapy compared with usual treatment were disappointing. 17 A cognitive behaviour therapy based “transdiagnostic” treatment for all eating disorders, including cases of anorexia where body mass index is above 15, has shown promise however. 18

Expert consensus favours long term, wide ranging, complex treatments using psychodynamic understanding, systemic principles, and techniques borrowed from motivational enhancement therapy and dialectical behavioural therapy (box 2). These treatments should be delivered in various settings that cater for the level of intensity and degree of medical monitoring and care needed. The coordinated working of a wide range of medical and psychiatric services that do not usually work together will be needed. Because of the age group affected, and the time span involved, patients' care often undergoes many transitions. These are peak times for relapse and decompensation.

Box 2 Psychotherapies available for managing anorexia nervosa

Individual therapy.

- Structured individual treatments are usually offered as a weekly one hour session with a therapist trained in the management of eating disorders and in the therapy model used

Cognitive analytic therapy

- This psychotherapy uses letters and diagrams to examine habitual patterns of behaviour around other people and to experiment with more flexible responses

Cognitive behaviour therapy

- This psychotherapy explores feelings, educates patients about body chemistry, and challenges the automatic thoughts and assumptions behind behaviour in anorexia

Interpersonal psychotherapy

- This psychotherapy maps out a person's network of relationships, selects a focus—such as role conflict, transition, or loss—and works to generate new ways to deal with distress

Motivational enhancement therapy

- This psychotherapy uses interviewing techniques derived from work with substance misuse to reframe “resistance” to change as “ambivalence” about change, and to nurture and amplify healthy impulses

Dynamically informed therapies

- These therapies may also result in weight gain and recovery provided the patient is aware of the risk of irreversible physical damage or death and acknowledges that certain boundaries (for example, that they must be weighed weekly, examined monthly by a doctor, and admitted to hospital if weight continues on a downward trend) are observed. The therapies involve talking, art, music, and movement

Group therapy

- There is little evidence that therapy for patients with anorexia benefits from being delivered in group sessions rather than individual sessions; in fact, group therapy may even worsen the problem. However, dialectical behaviour therapy offers structured groups in parallel with individual sessions. This therapy teaches skills that help patients to tolerate distress, soothe their feelings, and manage interpersonal relationships

Family work

- The term “family work” covers any intervention that harnesses the strengths of the family in tackling the patient's disorder or that tries to deal with the family's stress in the face of it. It includes family therapies, support groups, and psychoeducational input

Conjoint therapy

- Evidence points to the effectiveness of the Maudsley model of family therapy and similar interventions focused on eating disorders. Whole families—or at least the parents and the patient—attend counselling sessions together, which can cause intolerable emotional stress

Separated family therapy

- The patient and the parents attend separate meetings, sometimes with two different therapists. This form of therapy seems to be as effective as conjoint therapy, particularly for older patients, and involves lower levels of expressed emotion

Multifamily groups

- Such groups provide a novel way of empowering parents by means of peer support and help from a therapist. Several families, including the patients, meet together for intensive sessions that often last the whole day and include eating together

Relatives' and carers' support groups

- These groups range from self help meetings to highly structured sessions led by a therapist that aim to teach psychosocial and practical skills to help patients with anorexia to recover while avoiding unnecessary conflict. Most encompass at least some educational input about the nature of anorexia

Early on, especially in younger patients, motivation for treatment lies with parents, schoolteachers, or medical professionals. The guiding principle of motivational enhancement is to acknowledge and explore rather than fight the patient's ambivalence about recovery. Treatment is more effective when the therapist and the patient work together against the anorexia. Such a relationship may allow the patient to be treated without having to invoke the Mental Health Act. Motivation is not an all or nothing battle to be won before treatment can start—it must be actively engendered throughout the treatment.

TIPS FOR NON-SPECIALISTS

- Recovery takes years rather than weeks or months, and patients must accept that they should attain a normal weight—refeeding alone may lead to relapse

- Trends should be monitored by weighing, which needs to be managed skilfully so it does not become a battleground

- No cut off weight or body mass index exists because many other factors influence risk

- Substance misuse—including alcohol, deliberate overdoses, or misuse of prescribed insulin—greatly increases risk

- Weight fluctuations and binge-purge methods (rather than pure restriction) increase risk

- Depression, anxiety, and family arguments are probably secondary to the disorder, not underlying causes, so the anorexia should be treated first

- Medication has little benefit in anorexia and the risk of dangerous side effects is high in malnourished patients

- Try to involve the family—encourage calm firmness and assertive care

Family work is the only well researched intervention that has a beneficial impact. 19 Family work teaches the family and patient to be aware of the perpetuating features of the disorder. Fury, anger, and fighting lead to entrenched symptoms but too much permissiveness encourages the illness by allowing it to become an accepted response to stress, or—if the family will do anything to encourage the patient to eat—a route to providing “secondary gain” from the illness. Support of carers is essential to maintain the firm but sympathetic boundaries conducive to recovery

Early studies on teenagers with relatively recent onset anorexia showed that therapy involving the whole family was superior to treating just the patient. Further studies showed that, if tolerated, sessions involving the family and patient together gave the best results in terms of the family's psychological adjustment, but that weight gain was greater when families were seen separately from the patient. 19 Both types of family intervention were more effective than individual work. More recently, “multi-family groups” have been piloted. 20

The Maudsley group compared individual focused dynamic therapy, dynamically informed family therapy, individual cognitive analytic therapy, and “treatment as usual” over the course of a year. 21 The dynamically informed therapies—both family and individual—produced the best results. The study showed that severely ill adults with anorexia could be managed as outpatients, and it highlighted the benefits of continuity of care by one therapist and of the expertise provided. However, nothing can be concluded about the specific model of therapy provided.

What is it like to experience anorexia nervosa?

At first I believed my thoughts were normal when I looked in the mirror—you don't expect your eyes to lie. I felt such self loathing that I drastically reduced my food intake and did a lot of exercise. I felt better about myself and decided that once I'd lost a pound or two I would eat normally again. When it came to it I was too scared. It felt good to lose a couple of pounds but it became addictive. If I did a certain amount of exercise one day, the next day I had to do at least the same amount. I ended up feeling physically rubbish, but my mind said I'm a horrible person who deserves pain.

Paranoia sets in. You're convinced people think you are fat even when they say you are not. Your mind tells you they are lying, until you find you can't trust anyone. Living with anorexia is a constant battle between two evils. On one hand eating feels like an evil thing, but other people see that very belief as the evil. When I feel I really must starve or exercise I get angry with the nurses. Other times it's a relief though, because at least they take the responsibility away from me.

Is drug treatment effective?

The evidence base for the use of drugs in anorexia nervosa is poor. Antidepressants are often used to treat depressive symptoms but have limited success. The well documented benefits of antidepressants in bulimia nervosa 4 do not extend to anorexia, and the benefit from selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in preventing relapse after weight gain is unclear. Case reports describe the benefit of antipsychotic drugs such as olanzapine to promote weight gain. This success may be attributable to symptomatic relief of anxiety and increased appetite, rather than any effect on core pathology. Harmful effects of drugs, particularly the appearance of a long QT interval, with the risk of dangerous cardiac dysrhythmias, are more likely in patients who are malnourished and have electrolyte abnormalities.

What affects recovery and what is the prognosis?

A premature mortality rate of 20% was seen in an inpatient cohort, and a large proportion of cases took six to 12 years to resolve. 11 Bingeing and vomiting at low weight greatly increase mortality compared with purely restrictive starvation. Comorbidity is associated with bleaker prognosis. More recently, full recovery has been demonstrated even after 21 years of chronic severe anorexia nervosa. 12

Criteria are available for assessing recovery from anorexia nervosa. 11 The capacity to undertake normal levels of exercise and activity are also important. If the patient is given renutrition and care to protect against irreversible damage during the acute illness, cardiovascular function, immune function, fertility, and bone density can all return to healthy levels. Bone recovery takes years rather than months, so patients should protect the spine and pelvis in particular against gymnastic activity too early after weight gain. Even when a person has developed the crucial motivation to tolerate weight gain and explored the possibility of living with values other than those imposed by the cult of thinness, psychological recovery is difficult as the challenges of a rekindled adolescence must be faced.

ADDITIONAL EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES

Resources for healthcare professionals.

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence ( www.nice.org.uk )—Several guidelines are available that cover anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and atypical eating disorders

- American Psychiatric Association ( www.psych.org/psych_pract/treatg/pg/EatingDisorders3ePG_04-28-06.pdf )—A recently published guideline on the treatment of patients with eating disorders

- The Edinburgh Anorexia Nervosa Intensive Treatment Team ( www.anitt.org.uk )—This site contains a detailed clinical pathway for anorexia nervosa

- Institute of Psychiatry/Maudsley Hospital ( www.iop.kcl.ac.uk/ )—This site has good information and downloadable PDFs on medical complications of eating disorders and is kept up to date with research development

- Treasure J. Anorexia nervosa: a survival guide for families, friends and sufferers. Hove: Psychology Press, 1997

Resources for patients and carers

- Beating Eating Disorders ( www.edauk.com )—The Eating Disorders Association site has good information about the eating disorders network in the United Kingdom, resource lists, and details of local self help and support groups

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence ( www.nice.org.uk )—This site also contains a patient and carer version of the NICE guidelines

- Bloomfield S. Eating disorders: helping your child recover . Norwich: Eating Disorders Association, 2006

- Bryant-Waugh R, Lask B. Eating disorders: a parents' guide. Revised ed. Hove: Brunner-Routledge, 2004

Competing interests: None declared.

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Anorexia nervosa is a food intake disorder. characterized by a cute weight loss that it could cause. severe psychosomatic problems [1]. Diagnostic criteria for Anorexia nervosa. include an intense ...

This is a general overview of Anorexia Nervosa by reviewing around 20 research and studies from the past and present, compromising with its etiology, psychosocial impacts, treatment, and ...

PDF | On Dec 1, 2018, Sarah Cooper and others published Anorexia Nervosa: Pathophysiology, Treatment, and Genetic Considerations | Find, read and cite all the research you need on ResearchGate

For eating disorders, there are some methodological problems regarding epidemiological research. Eating disorders are relatively rare in the community and help seeking is often avoided or delayed, for example for reasons of denial (particularly in anorexia nervosa) or stigma and shame (particularly in bulimia nervosa).

Anorexia nervosa is a complex psychiatric illness associated with food restriction and high mortality. Recent brain research in adolescents and adults with anorexia nervosa has used larger sample sizes compared with earlier studies and tasks that test specific brain circuits. Those studies have produced more robust results and advanced our ...

Anorexia nervosa is an important cause of physical and psychosocial morbidity. Recent years have brought advances in understanding of the underlying psychobiology that contributes to illness onset and maintenance. Genetic factors infl uence risk, psychosocial and interpersonal factors can trigger onset, and changes in neural networks can sustain the illness. Substantial advances in treatment ...

Anorexia nervosa is associated with high personal and economic costs for sufferers, their relatives and society. Evidence-based practice guidelines aim to support all groups involved in the care of patients with anorexia nervosa by providing them with scientifically sound recommendations regarding diagnosis and treatment.