Home — Essay Samples — Social Issues — Gender Discrimination — Gender Representation in the Media

Gender Representation in The Media

- Categories: Gender Discrimination

About this sample

Words: 772 |

Published: Jan 29, 2024

Words: 772 | Pages: 2 | 4 min read

Table of contents

Introduction, body paragraph 1, body paragraph 2, body paragraph 3, body paragraph 4, thesis statement:.

- Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media

- Annenberg Inclusion Initiative

- Women's Media Center

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Prof Ernest (PhD)

Verified writer

- Expert in: Social Issues

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

1 pages / 734 words

2 pages / 961 words

4 pages / 1597 words

1 pages / 1138 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Gender Discrimination

In Greek mythology, Pallas Athena, also known simply as Athena, is one of the most revered and well-known goddesses. She is often depicted as the goddess of wisdom, courage, inspiration, civilization, law and justice, strategic [...]

Nathaniel Hawthorne's The Scarlet Letter is a renowned novel that explores the complex themes of sin, guilt, and redemption in Puritan society. One striking character in the narrative is Pearl, the illegitimate daughter of [...]

Diversity in the classroom refers to the variety of differences that exist among students, including but not limited to race, ethnicity, gender, socioeconomic status, language, culture, and learning styles. In today's globalized [...]

Beauty standards have been a prominent aspect of American culture for decades, influencing the way individuals perceive themselves and others. These standards are often perpetuated through various media platforms, such as [...]

Gender equality is not only a fundamental human right, but a necessary foundation for a prosperous and sustainable world. In this assignment we are going to discuss gender inequality mainly focusing on women. Gender lines are [...]

Till this day, gender conflict in society is an on-going concern. Through generations men and women have been limited to their ability based on society’s labels that are attached to each gender in which the narrator experiences [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Int J Environ Res Public Health

- PMC10218532

Gender and Media Representations: A Review of the Literature on Gender Stereotypes, Objectification and Sexualization

Media representations play an important role in producing sociocultural pressures. Despite social and legal progress in civil rights, restrictive gender-based representations appear to be still very pervasive in some contexts. The article explores scientific research on the relationship between media representations and gender stereotypes, objectification and sexualization, focusing on their presence in the cultural context. Results show how stereotyping, objectifying and sexualizing representations appear to be still very common across a number of contexts. Exposure to stereotyping representations appears to strengthen beliefs in gender stereotypes and endorsement of gender role norms, as well as fostering sexism, harassment and violence in men and stifling career-related ambitions in women. Exposure to objectifying and sexualizing representations appears to be associated with the internalization of cultural ideals of appearance, endorsement of sexist attitudes and tolerance of abuse and body shame. In turn, factors associated with exposure to these representations have been linked to detrimental effects on physical and psychological well-being, such as eating disorder symptomatology, increased body surveillance and poorer body image quality of life. However, specificities in the pathways from exposure to detrimental effects on well-being are involved for certain populations that warrant further research.

1. Introduction

As a social category, gender is one of the earliest and most prominent ways people may learn to identify themselves and their peers, the use of gender-based labels becoming apparent in infants as early as 17 months into their life [ 1 ]. Similarly, the development of gender-based heuristics, inferences and rudimentary stereotypes becomes apparent as early as age three [ 2 , 3 ]. Approximately at this age, the development of a person’s gender identity begins [ 4 ]—that is, the process through which a person tends to identify as a man, as a woman or as a vast spectrum of other possibilities (i.e., gender non-conforming, agender, genderfluid, etc.). These processes continue steadily throughout individuals’ lives as they receive and elaborate information about women and men and what it means to belong to either category, drawing from direct and indirect observations, social contact, personal elaborations and cultural representations [ 5 , 6 ]. As a result, social and mental representations of gender are extremely widespread, especially as a strictly binary construct, and can be argued to be ubiquitous in individual and social contexts.

Among the many sources of influence on gender representations, media occupies an important space and its relevance can be assessed across many different phenomena [ 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 ]. The ubiquity of media, the chronicity of individuals’ exposure to it and its role in shaping beliefs, attitudes and expectations have made it the subject of scientific attention. In fact, several theories have attempted to explore the mechanisms and psychological processes in which media plays a role, including identity development [ 12 , 13 , 14 ], scripts and schemas [ 15 ], cultivation processes [ 16 , 17 , 18 ] and socialization processes [ 5 , 6 ].

The public interest in the topic of gender has seen a surge in the last 10 years, in part due to social and political movements pushing for gender equality across a number of aspects, including how gender is portrayed in media representations. In the academic field as well, publications mentioning gender in their title, abstract or keywords have more than doubled from 2012 to 2022 [ 19 ], while publications mentioning gender in media representations have registered an even more dramatic increase, tripling in number [ 20 ]. Additionally, the media landscape has had a significant shift in the last decade, with the surge in popularity and subsequent addition of social media websites and apps to most people’s mediatic engagement [ 21 ].

The importance of media use in gender-related aspects, such as beliefs, attitudes, or roles, has been extensively documented. As reported in a recent review of the literature [ 22 ], several meta-analyses [ 17 , 23 , 24 ] showed support for the effects of media use on gender beliefs, finding small but consistent effect sizes. These effects appear to have remained present over the decades [ 25 ].

Particular attention has been given to stereotypical, objectifying and sexualizing representations, as portrayals that paint a restrictive picture of the complexity of human psychology, also producing sociocultural pressures to conform to gender roles and body types.

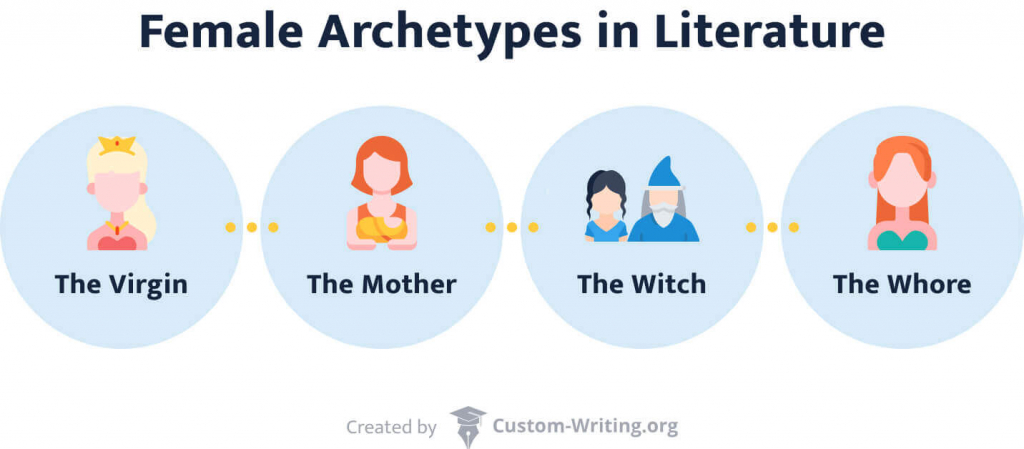

Gender stereotypes can be defined as an extremely simplified concept of attitudes and behaviors considered normal and appropriate for men and women in a specific culture [ 26 ]. They usually span several different areas of people’s characteristics, such as physical appearance, personality traits, behaviors, social roles and occupations. Stereotypical beliefs about gender may be divided into descriptive (how one perceives a person of a certain gender to be; [ 27 ]), prescriptive (how one perceives a person of a certain gender should be and behave; [ 28 , 29 ]) or proscriptive (how one perceives a person of a certain gender should not be and behave; [ 28 , 29 ]). Their content varies on the individual’s culture of reference [ 30 ], but recurring themes have been observed in western culture, such as stereotypes revolving around communion, agency and competence [ 31 ]. Women have stereotypically been associated with traits revolving around communion (e.g., supportiveness, compassion, expression, warmth), while men have been more stereotypically associated with agency (e.g., ambition, assertiveness, competitiveness, action) or competence (e.g., skill, intelligence). Both men and women may experience social and economic penalties (backlash) if they appear to violate these stereotypes [ 29 , 32 , 33 ].

Objectification can be defined as the viewing or treatment of people as objects. Discussing ways in which people may be objectified, Nussbaum first explored seven dimensions: instrumentality (a tool to be employed for one’s purposes); denial of autonomy (lacking self-determination, or autonomy); inertness (lacking in agency or activity); fungibility (interchangeable with others of the same type); violability (with boundaries lacking integrity and permissible to break into); ownership (possible to own or trade); denial of subjectivity (the person’s feelings or experiences are seen as something that does not need to be considered) [ 34 ].

In its initial definition by Fredrickson and Roberts [ 35 ], objectification theory had been offered as a framework to understand how the pervasive sexual objectification of women’s bodies in the sociocultural context influenced their experiences and posed risks to their mental health—a phenomenon that was believed to have uniquely female connotations. In their model, the authors theorized that a cultural climate of sexual objectification would lead to the internalization of objectification (viewing oneself as a sexual and subordinate object), which would in turn lead to psychological consequences (e.g., body shame, anxiety) and mental health risks (e.g., eating disorders, depression). Due to the pervasiveness of the cultural climate, objectification may be difficult to detect or avoid, and objectification experiences may be perceived as normative.

Sexual objectification, in which a person is reduced to a sexual instrument, can be construed to be a subtype of objectification and, in turn, is often defined as one of the types of sexualization [ 36 ]. As previously discussed by Ward [ 37 ], it should be made clear that the mere presence of sexual content, which may be represented in a positive and healthy way, should not be conflated with sexualized or objectifying representations.

The American Psychological Association’s 2007 report defines sexualization as a series of conditions that stand apart from healthy sexuality, such as when a person’s value is perceived to come mainly from sexual appeal or behavior, when physical attractiveness is equated to sexual attractiveness, when a person is sexually objectified or when sexuality is inappropriately imposed on a person [ 36 ]. Sexualization may involve several different contexts, such as personal, interpersonal, and cultural. Self-sexualization involves treating oneself as a sexual object [ 35 ]. Interpersonal contributions involve being treated as sexual objects by others, such as family or peers [ 38 , 39 ]. Finally, contributions by cultural norms, expectations and values play a part as well, including those spread by media representations [ 36 ]. After this initial definition, sexualization as a term has also been used by some authors (e.g., Zurbriggen & Roberts [ 40 ]) to refer to sexual objectification specifically, while others (e.g., Bigler and colleagues [ 41 ]) stand by the APA report’s broader meaning. In this section, we will explore scientific literature adopting the latter.

These portrayals have been hypothesized to lead to negative effects on people’s well-being on a mental and physical level, as well as bearing partial responsibility for several social issues, such as sexism, gender discrimination and harassment. However, the pathways that lead from an individual’s relationship with media to these detrimental effects can be complex. Furthermore, they seem to involve specificities for men and women, as well as for different sexual orientations. A wealth of publications has been produced on these themes and, to the authors’ knowledge, no recent review has attempted to synthesize their findings.

The present article aims to summarize the state of the art of research on stereotyping, sexualization and objectification in gender and media representations. A focus will be placed on the definitions of these concepts, the media where they occur, and verifying whether any changes over time are detectable or any specificities are present. The possible effects of these representations on people’s well-being will be explored as well.

A search of the literature was conducted on scientific search engines (APA PsycArticles, CINAHL Complete, Education Source, Family Studies Abstracts, Gender Studies Database, MEDLINE, Mental Measurements Yearbook, Sociology Source Ultimate, Violence & Abuse Abstracts, PUBMED, Scopus, Web of Science) to locate the most relevant contributions on the topic of media and gender representation, with a particular focus on stereotypes, objectification and sexualization, their presence in the media and their effects on well-being. Keywords were used to search for literature on the intersection of the main topics: media representation (e.g., media OR representation* OR portrayal*), gender (e.g., gender OR sex OR wom* OR m*n) and stereotypes, objectification and sexualization (e.g., stereotyp*, objectif*, sexualiz*). In some cases, additional keywords were used for the screening of studies on specific media (e.g., television, news, social media). When appropriate, further restrictions were used to screen for studies on effects or consequences (e.g., effect* OR impact* OR consequence* OR influence* OR outcome*). Inclusion criteria were the following: (a) academic articles (b) pertaining to the field of media representations (c) pertaining to gender stereotypes, objectification or sexualization. A dataset of 195 selected relevant papers was created. Thematic analysis was conducted following the guidelines developed by Braun and Clarke [ 42 ], in order to outline patterns of meaning across the reviewed studies. The process was organized into six phases: (1) familiarization with the data; (2) coding; (3) searching for themes; (4) reviewing themes; (5) defining and naming themes; and (6) writing up. After removing duplicates and excluding papers that did not meet the inclusion criteria, a total of 87 articles were included in the results of this review. The findings were discussed among researchers (LR, FS, MNP and TT) until unanimous consensus was reached.

2.1. Stereotypical Portrayals

Gender stereotypes appear to be flexible and responsive to changes in the social environment: consensual beliefs about men’s and women’s attributes have evolved throughout the decades, reflecting changes in women’s participation in the labor force and higher education [ 31 , 43 ]. Perceptions of gender equality in competence and intelligence have sharply risen, and stereotypical perceptions of women show significant changes: perceptions of women’s competence and intelligence have surpassed those relative to men, while the communion aspect appears to have shifted toward being even more polarized on being typical of women. Other aspects, such as perceptions of agency being more typical of men, have remained stable [ 31 ].

Despite these changes, gender representation in the media appears to be frequently skewed toward men’s representation and prominently features gender stereotypes. On a global scale, news coverage appears to mostly feature men, especially when considering representation as expert voices, where women are still underrepresented (24%) despite a rise in coverage in the last 5 years [ 44 ]. Underrepresentation has also been reported in many regional and national contexts, but exact proportions vary significantly in the local context. Male representation has been reported to be greater in several studies, with male characters significantly outnumbering female characters [ 45 ], doing so in male-led and mixed-led shows but not in female-led shows [ 46 ] in children’s television programming—a key source of influence on gender representations. Similar results have been found regarding sports news, whose coverage overwhelmingly focuses on men athletes [ 47 , 48 ] and where women are seldom represented.

Several analyses of television programs have also shown how representations of men and women are very often consistent with gender stereotypes. Girls were often portrayed as focusing more on their appearance [ 45 ], as well as being judged for their appearance [ 49 ]. The same focus on aesthetics was found in sports news coverage, which was starkly different across genders, and tended to focus on women athletes’ appearance, featuring overly simplified descriptions (vs. technical language on coverage of men athletes) [ 48 ]. In addition, coverage of women athletes was more likely in sports perceived to be more feminine or gender-appropriate [ 47 , 48 , 50 ]. Similarly, women in videogames appear to be both underrepresented and less likely to be featured as playable characters, as well as being frequently stereotyped, appearing in the role of someone in need of rescuing, as love interests, or cute and innocent characters [ 51 ]. In advertising as well, gender stereotypes have often been used as a staple technique for creating relatability, but their use may lead to negative cross-gender effects in product marketing [ 52 ] while also possibly furthering social issues. Hust and colleagues found that in alcohol advertisements, belief in gender stereotypes was the most consistent predictor of intentions to sexually coerce, showing significant interaction effects with exposure to highly objectifying portrayals [ 53 ]. Representation in advertising prominently features gender stereotypes, such as depicting men in professional roles more often, while depicting women in non-working, recreational roles, especially in countries that show high gender inequality [ 54 ]. A recent analysis of print ads [ 55 ] confirmed that some stereotypes are still prominent and, in some cases, have shown a resurgence, such as portraying a woman as the queen of the home; the study also found representations of women in positions of empowerment are, however, showing a relative increase in frequency. Public support, combined with market logic, appears to be successfully pushing more progressive portrayals in this field [ 56 ].

Both skewed representation and the presence of stereotypes have been found to lead to several negative effects. Gender-unequal representation has been found to stifle political [ 57 ] and career [ 58 ] ambition, as well as foster organizational discrimination [ 59 ]. Heavy media use may further the belief in gender stereotypes and has been found to be linked to a stronger endorsement of traditional gender roles and norms [ 60 ], which in turn may be linked to a vast number of detrimental health effects. In women, adherence and internalization of traditional gender roles have been linked to greater symptoms of depression and anxiety, a higher likelihood of developing eating disorders, and lower self-esteem and self-efficacy [ 36 , 61 , 62 , 63 ]. In men as well, adherence to traditional masculine norms has been linked to negative mental health outcomes such as depression, psychological distress and substance abuse [ 64 ], while also increasing the perpetration of risky behaviors [ 65 , 66 ] and intimate partner violence [ 65 , 67 ].

2.2. Objectifying Portrayals

Non-sexual objectifying representations appear to have been studied relatively little. They have been found to be common in advertising, where women are often depicted as purely aesthetic models, motionless and decorative [ 68 ]. They may also include using a woman’s body as a supporting object for the advertised product, as a decorative object, as an ornament to draw attention to the ad, or as a prize to be won and associated with the consumption of the advertised product [ 55 ].

The vast majority of the literature has focused on the sexual objectification of women. This type of representation has been reported to be very common in a number of contexts and across different media [ 69 ], and several studies (see Calogero and colleagues’ or Roberts and colleagues’ review [ 69 , 70 ]) have found support for the original model’s pathway [ 35 ]. Following experimental models expanded on the original (e.g., Frederick and colleagues or Roberts and colleagues [ 69 , 71 ]), highlighting the role of factors such as the internalization of lean or muscular ideals of appearance, finding evidence for negative effects on well-being and mental health through the increase in self-objectification and the internalization of cultural ideals of appearance [ 71 , 72 ].

Sexual objectification also appears to be consistently linked to sexism. For both women and men, the perpetration of sexual objectification was significantly associated with hostile and benevolent sexism, as well as the enjoyment of sexualization [ 73 ]. Enjoyment of sexualization, in turn, has been found to be positively associated with hostile sexism in both men and women, positively associated with benevolent sexism in women and negatively in men [ 74 ].

Exposure to objectifying media in men has been found to increase the tendency to engage in sexual coercion and harassment, as well as increasing conformity to gender role norms [ 75 ]. Consistently with the finding that perpetration of objectification may be associated with a greater men’s proclivity for rape and sexual aggression [ 76 ], a study conducted by Hust and colleagues found that exposure to objectifying portrayals of women in alcohol advertising was also a moderator in the relationship between belief in gender stereotypes and intentions to sexually coerce. Specifically, participants who had a stronger belief in gender stereotypes reported stronger intentions to sexually coerce when exposed to slightly objectifying images of women. Highly objectifying images did not yield the same increase—a result interpreted by the authors to mean that highly objectified women were perceived as sexually available and as such less likely to need coercion, while slightly objectified women could be perceived as more likely to need coercion [ 53 ].

Research on objectification has primarily focused on women, in part due to numerous studies suggesting that women are more subject to sexual objectification [ 73 , 77 , 78 , 79 , 80 ], as well as suffering the consequences of sexual objectification more often [ 81 ]. However, sexually objectifying portrayals seem to have a role in producing negative effects on men as well, although with partially different pathways. In men, findings about media appearance pressures on body image appear to be mixed. Previous meta-analyses found either a small average effect [ 82 ] or no significant effect [ 72 ]. A recent study found them to be significantly associated with higher body surveillance, poorer body image quality of life and lower satisfaction with appearance [ 71 ]. Another study, however, found differing relationships regarding sexual objectification: an association was found between experiences of sexual objectification and internalization of cultural standards of appearance, body shame and drive for muscularity, but was not found between experiences of sexual objectification and self-objectification or body surveillance [ 83 ]: in the same study, gender role conflict [ 84 ] was positively associated to the internalization of sociocultural standards of appearance, self-objectification, body shame and drive for muscularity, suggesting the possibility that different pathways may be involved in producing negative effects on men. Men with body-image concerns experiencing gender role conflict may also be less likely to engage in help-seeking behaviors [ 85 , 86 ]. This is possibly due to restrictive emotionality associated with the male gender role leading to more negative attitudes toward help-seeking, as found in a recent study by Nagai, [ 87 ], although this study finds no association with help-seeking behavior, conflicting with previous ones, and more research is needed.

Finally, specificities related to sexual orientation regarding media and objectification appear to be present. A set of recent studies by Frederick and colleagues found that gay men, lesbian women and bisexual people share with heterosexual people many of the pathways that lead from sociocultural pressures to internalization of thin/muscular ideals, higher body surveillance and a lower body image quality of life [ 71 , 88 ], leading the authors to conclude that these factors’ influence applies regardless of sexual orientation. However, their relationship with media and objectification may vary. Gay and bisexual men may face objectification in social media and dating apps rather than in mainstream media and may experience more objectification than heterosexual men [ 89 ]. In Frederick and colleagues’ studies, gay men reported greater media pressures, body surveillance, thin-ideal internalization, and self-objectification compared to heterosexual men; moreover, bisexual men appeared to be more susceptible to ideal internalization, displaying stronger paths from media appearance pressures to muscular-ideal internalization compared to heterosexual men; lesbian women, instead, demonstrated weaker relationships between media pressures and body image outcomes [ 71 , 88 ]. Consistently with previous studies suggesting a heightened susceptibility to social pressures [ 90 ], bisexual women appeared to be more susceptible to media pressures relative to other groups [ 88 ]. Another recent study of lesbian and bisexual women supported previous evidence for the pathway from the internalization of cultural appearance standards to body surveillance, body shame and eating disorder symptoms; however, it found no significant connection between experiences of objectification and eating disorder symptoms [ 91 ].

2.3. Sexualized Portrayals

Several studies have found sexualizing media representations to be commonplace across a number of different media contents and across different target demographics (i.e., children, adolescents or adults) and genres. Reports of common sexualized representations of women are found in contexts such as television programs [ 92 ], movies [ 93 , 94 , 95 , 96 ], music videos [ 97 , 98 ], advertising [ 54 , 55 ], videogames [ 51 , 99 , 100 ], or magazines [ 101 ].

Exposure to sexualized media has been theorized to be an exogenous risk factor in the internalization of sexualized beliefs about women [ 41 ], as well as one of the pathways to the internalization of cultural appearance ideals [ 102 ]. Daily exposition to sexualized media content has been consistently linked to a number of negative effects. Specifically, it has been found to lead to higher levels of body dissatisfaction and distorted attitudes about eating through the internalization of cultural body ideals (e.g., lean or muscular) in both men and women [ 71 ]. It has also been associated with a higher chance of supporting sexist beliefs in boys [ 103 ], and of tolerance toward sexual violence in men [ 104 ]. Furthermore, exposure to sexualized images has been linked to a higher tolerance of sexual harassment and rape myth acceptance [ 76 ]. Exposure to reality TV programs consistently predicted self-sexualization for both women and men, while music videos did so for men only [ 103 ]. Internalized sexualization, in turn, has been linked to a stronger endorsement of sexist attitudes and acceptance of rape myths [ 105 ], while also being linked to higher levels of body surveillance and body shame in girls [ 106 ]. Internalization of media standards of appearance has been linked to body surveillance in both men and women, as well as body surveillance of the partner in men [ 107 ].

As a medium, videogames have been studied relatively little and have produced less definite results. This medium can offer the unique dynamic of embodiment in a virtual avatar, which has been hypothesized to be able to lead to a shift in self-perception (the “Proteus effect”, as formulated by Yee & Bailenson, [ 108 ]). While some studies have partially confirmed this effect, showing that exposure to sexualized videogame representations can increase self-objectification [ 109 , 110 , 111 ], others [ 112 ] have not found the same relationship. Furthermore, while a study has found an association between sexualized representations in videogames, tolerance of sexual abuse of women and rape myth acceptance [ 113 ], and in another, it was linked to a decreased real-life belief in women’s competence [ 114 ], a recent meta-analysis [ 115 ] found no effect of the presence of sexualized content on well-being, sexism or misogyny.

Research on social media has also shown some specificities. Social media offers the unique dynamic of being able to post and disseminate one’s own content and almost always includes built-in mechanisms for user-generated feedback (e.g., likes), as well as often being populated by one’s peers, friends and family rather than strangers. Sites focusing on image- or video-based content (e.g., Instagram, TikTok) may be more prone to eliciting social comparison and fostering the internalization of cultural appearance ideals, resulting in more associations to negative body image when compared to others that have the same capabilities but offer text-based content as well (e.g., Facebook) [ 116 ]. Social media appears to foster social comparison, which may increase appearance-based concerns [ 117 ]. Consistently with previous research, exposure to sexualized beauty ideals on social media appeared to be associated with lower body satisfaction; exposure to more diverse standards of appearance, instead, was associated with increased body satisfaction and positive mood, regardless of image sexualization [ 116 , 118 ].

3. Discussion

3.1. critical discussion of evidence.

The reviewed evidence (summarized in Table 1 ) points to the wide-ranging harmful effects of stereotyping, objectifying and sexualizing media portrayals, which are reported to be still both common and pervasive. The links to possible harms have also been well documented, with a few exceptions.

Summary of findings.

| Gender Stereotypes | Objectification | Sexualization | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Common | Common | Common | |

| | : Higher belief in gender stereotypes; endorsement of traditional gender roles. : reduction of political and career-related ambition; organizational discrimination. | : Internalization of cultural ideals of appearance; increase in self-objectification; hostile and benevolent sexism; enjoyment of sexualization. : proclivity for sexual coercion (moderator); conformity to gender role norms. | : Internalization of cultural ideals of appearance; self-sexualization. : higher support of sexist beliefs (boys); tolerance toward sexual violence. |

| | : Symptoms of depression and anxiety; higher likelihood of eating disorders; lower self-esteem and self-efficacy. : symptoms of depression, psychological distress; higher proclivity for sexual coercion; substance abuse, increased perpetration of risky behaviors, intimate partner violence. | : higher likelihood of eating disorders and disordered eating behaviors | : higher levels of body dissatisfaction; body surveillance; distorted attitudes about eating; higher endorsement of sexist attitudes; acceptance of rape myths. : body shame (girls). : body surveillance of the partner. |

| | – | : media appearance pressures on body image | Effects of exposure to videogames |

| Virtual reality | Non-sexual portrayals; specificities of sexual minorities; virtual reality | Specificities of videogames; specificities of sexual minorities; virtual reality |

These representations, especially but not exclusively pertaining to women, have been under social scrutiny following women’s rights movements and activism [ 119 ] and can be perceived to be politically incorrect and undesirable, bringing an aspect of social desirability into the frame. Positive attitudes toward gender equality also appear to be at an all-time high across the western world [ 120 , 121 ], a change that has doubtlessly contributed to socio-cultural pressure to reduce harmful representations. Some media contexts (e.g., advertising and television) seem to have begun reflecting this change regarding stereotypes, attempting to either avoid harmful representations or push more progressive portrayals. However, these significant changes in stereotypes (e.g., regarding competence) have not necessarily been reflected in women’s lives, such as their participation in the labor force, leadership or decision-making [ 31 , 122 , 123 ]. Objectifying or sexualizing representations do not seem to be drastically reduced in prevalence. Certainly, many influences other than media representations are in play in this regard, but their effect on well-being has been found to be pervasive and consistent. Despite widespread positive attitudes toward gender equality, the persistence of stereotypical, objectifying and sexualizing representations may hint at the continued existence of an entrenched sexist culture which can translate into biases, discrimination and harm.

Despite some conflicting findings, the literature also hints at the existence of differences in how media pressures appear to affect men and women, as well as gay, lesbian and bisexual people. These may point to the possibility of some factors (e.g., objectification) playing a different role across different people in the examined pathways, an aspect that warrants caution when considering possible interventions and clinical implications. In some cases, the same relationship between exposure to media and well-being may exist, but it may follow different pathways from distal risk factors to proximal risk factors, as in the case of gender role conflict for men or body shame for lesbian and bisexual women. However, more research is needed to explore these recent findings.

Different media also appear to feature specificities for which more research is needed, such as videogames and social media. The more interactive experiences offered by these media may play an important role in determining their effects, and the type of social media needs to be taken into consideration as well (image- or video-based vs. text-based). Moreover, the experiences of exposure may not necessarily be homogenous, due to the presence of algorithms that determine what content is being shown in the case of social media, and due to the possibility of player interaction and avatar embodiment in the case of videogames.

Past findings [ 37 , 69 ] about links with other social issues such as sexism, harassment and violence appear to still be relevant [ 67 , 73 , 103 , 105 ]. The increases in both tolerance and prevalence of sexist and abusive attitudes resulting from exposure to problematic media representations impact the cultural climate in which these phenomena take place. Consequently, victims of discrimination and abuse living in a cultural climate more tolerant of sexist and abusive attitudes may experience lower social support, have a decreased chance of help-seeking and adopt restrictive definitions for what counts as discrimination and abuse, indirectly furthering gender inequalities.

Exploring ways of reducing risks to health, several authors [ 22 , 41 , 75 ] have discussed media literacy interventions—that is, interventions focused on teaching critical engagement with media—as a possible way of reducing the negative effects of problematic media portrayals. As reported in McLean and colleagues’ systematic review [ 124 ], these interventions have been previously shown to be effective at increasing media literacy, while also improving body-related outcomes such as body satisfaction in boys [ 125 ], internalization of the thinness ideal in girls [ 125 ], body size acceptance in girls [ 126 ] and drive for thinness in girls and boys [ 127 ]. More recently, they were also shown to be effective at reducing stereotypical gender role attitudes [ 128 ], as well as fostering unfavorable attitudes toward stereotypical portrayals and lack of realism [ 129 ]. Development and promotion of these interventions should be considered when attempting to reduce negative media-related influences on body image. It should be noted, however, that McLean and colleagues’ review found no effect of media literacy interventions on eating disorder symptomatology [ 124 ], which warrants more careful interventions.

Furthermore, both internal (e.g., new entrants’ attitudes in interpersonal or organizational contexts) and external (e.g., pressure from public opinion) sociocultural pressures appear to have a strong influence in reducing harmful representations [ 55 , 56 ]. Critically examining these representations when they appear, as well as voicing concerns toward examples of possibly harmful representations, may promote more healthy representations in media. As documented by some studies, the promotion of diverse body representations in media may also be effective in reducing negative effects [ 70 , 118 ].

3.2. Limitations

The current review synthesizes the latest evidence on stereotyping, objectifying and sexualizing media representations. However, limitations in its methodology are present and should be taken into consideration. It is not a systematic review and may not be construed to be a complete investigation of all the available evidence. Only articles written in the English language have been considered, which may have excluded potentially interesting findings written in other languages. Furthermore, it is not a meta-analysis, and as such cannot be used to draw statistical conclusions about the surveyed phenomena.

3.3. Future Directions

While this perception is limited by the non-systematic approach of the review, to what we know, very few studies appear to be available on the relationship between media representation and non-sexual objectification, which may provide interesting directions to explore in relation to autonomy, violability or subjectivity, as was attempted in the context of work and organizations [ 130 ].

More cross-cultural studies (e.g., Tartaglia & Rollero [ 54 ]) would also prove useful in exploring differences between cultural contexts, as well as the weight of different sociocultural factors in the relationship between media representation and gender.

More studies focusing on relatively new media (e.g., social media, videogames) would possibly help clear up some of the identified discrepancies and explore new directions for the field that take advantage of their interactivity. This is particularly true for niche but growing media such as virtual reality, in which the perception of embodiment in an avatar with different physical features than one’s own could prove to be important in sexualization and objectification. Only preliminary evidence [ 131 ] has been produced on the topic.

Studies to further explore the relationship between media representations, gender and sexual orientation would also be beneficial. As already highlighted by Frederick and colleagues [ 132 ], gay, lesbian and bisexual people may deal with a significantly different set of appearance norms and expectations [ 133 ], and face minority-related stresses [ 134 ] that can increase susceptibility to poorer body image and disordered eating [ 135 , 136 ]. Additionally, none of the reviewed studies had a particular focus on trans people, who may have different experiences relating to media and body image, as suggested by the differences in pathways found in a recent study [ 137 ]. Sexual orientation and gender identity should be kept into consideration when investigating these relationships, as their specificities may shed light on the different ways societal expectations influence the well-being of sexual minorities.

The examined literature on the topic also appears to feature specificities that need to be taken into account. As previously reported by Ward [ 37 ], the vast majority of the studies continue to be conducted in the United States, often on undergraduates, which limits the generalizability of the results to the global population. Given the abundance and complexity of the constructs, more studies examining the pathways from media exposure to well-being using methodologies such as path analysis and structural equation modeling may help clarify some of the discrepancies found in the literature about the same relationships.

Finally, as previously reported by many authors [ 37 , 69 , 138 ], sexualization, self-sexualization, objectification and self-objectification are sometimes either treated as synonymous or used with different definitions and criteria, which may add a layer of misdirection to studies on the subject. Given the divergences in the use of terminology, clearly stating one’s working definition of sexualization or objectification would possibly benefit academic clarity on the subject.

4. Conclusions

Consistent empirical evidence highlights the importance of media representations as a key part of sociocultural influences that may have consequences on well-being. Despite some notable progress, harmful representations with well-researched links to detrimental effects are still common across a number of different media. Exposure to stereotyping, objectifying and sexualized representations appears to consistently be linked to negative consequences on physical and mental health, as well as fostering sexism, violence and gender inequity. On a clinical level, interventions dealing with body image and body satisfaction should keep their influence into account. The promotion of institutional and organizational interventions, as well as policies aimed at reducing their influence, could also prove to be a protective factor against physical and mental health risks.

Funding Statement

This research received no external funding.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.S. and L.R.; methodology, T.T. and M.N.P.; writing—original draft preparation, F.S.; writing—review and editing, T.T. and M.N.P.; supervision, L.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

Visualizing the data: Women’s representation in society

Date: 25 February 2020

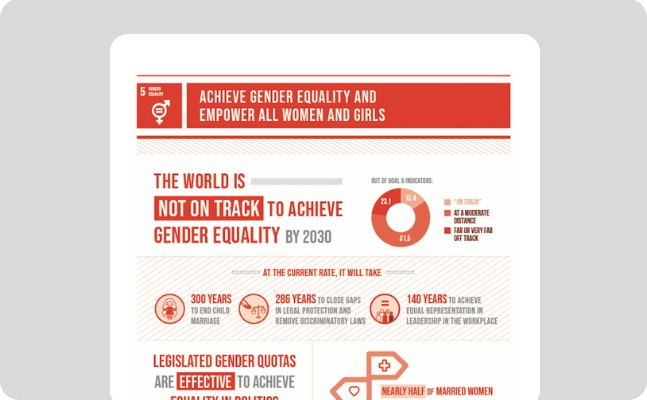

Women’s full and equal participation in all facets of society is a fundamental human right. Yet, around the world, from politics to entertainment to the workplace, women and girls are largely underrepresented.

The visualizations below take a closer look at this gender-imbalanced picture over time, revealing just how slow progress is. Rooted in patriarchal norms and traditions, the consequences are far-reaching with detrimental, negative consequences on the personal, economic and future well-being of women and girls, their families and the community at large.

Building a sustainable future for all, means leaving no one behind. Women and girls are critical to finding solutions to the biggest challenges we face today and must be heard, valued and celebrated throughout society to reflect their perspectives and choices for their future and that of the advancement of humanity.

How many more generations are needed for women and girls to realize their rights? Join Generation Equality to demand equal rights and opportunities or all. Share this piece today using #GenerationEquality, #IWD2020 and #CSW64.

Politics

Women’s political representation globally has doubled in the last 25 years. But, this only amounts to around 1 in 4 parliamentary seats held by women today.

Women continue to be significantly underrepresented in the highest political positions. In October 2019, there were only 10 women Head of State and 13 women Head of Government across 22 countries, compared with four Head of State and eight Prime Ministers across 12 countries in 1995.

Source: Inter-Parliamentary Union (Data as of 1 January 2020); Report of the UN Secretary-General E/CN.6/2020/3

In June 2019, the Fortune 500 hit a milestone with the most women CEOs on record. While every gain is a win, the sum as a whole is a bleak picture: Out of the 500 chief executives leading the highest-grossing firms, just under 7 per cent are women.

When looking at the workforce as a whole, the gender gap in labour force participation among prime working age adults (25 to 54) has stagnated over the past 20 years. Improved education among women has done little to shift deeply entrenched occupational segregation in developed and developing countries. Women continue to carry out a disproportionate share of unpaid care and domestic work. In developing countries, that includes arduous tasks such as water collection, for which women and girls are responsible in 80 per cent of households that do not have access to water on the premises.

Source: Fortune 500 (Data as of 1 June 2019); Catalyst ; Report of the UN Secretary-General E/CN.6/2020/3

Culture and sciences

Bestowed annually to recognize intellectual achievement and academic, cultural and scientific advances, the Nobel Prize has been awarded to more than 900 individuals in the course of its history from 1901 to 2019. Only 53 of the winners have been women, 19 in the categories of physics, chemistry, and physiology or medicine. Marie Curie became the first female laureate in 1903, when she and her husband won a joint Prize for physics. Eight years later she was solely awarded the Chemistry Prize, making her the only woman in history to win the Nobel Prize twice. Although women have been behind a number of scientific discoveries throughout history, just 30 per cent of researchers worldwide and 35 per cent of all students enrolled in STEM-related fields of study are women.

Source: The Nobel Foundation (Data as of 2019); Progress on the Sustainable Development Goals: The gender snapshot 2019 , UN Women

When it comes to equality of men and women in news media, progress has virtually ground to a halt. According to the largest study on the portrayal, participation and representation of women in the news media spanning 20 years and 114 countries, only 24 per cent of the persons heard, read about or seen in newspaper, television and radio news are women. A glass ceiling also exists for women news reporters in newspaper bylines and newscast reports, with 37 per cent of stories reported by women as of 2015, showing no change over the course of a decade. Despite the democratizing promise of digital media, women’s poor representation in traditional news media is also reflected in digital news, with women making up only 26 per cent of the people in Internet news stories and media news tweets. Only 4 per cent of traditional news and digital news stories clearly challenge gender stereotypes. Among other factors, stereotypes and the significant underrepresentation of women in the media play a significant role in shaping harmful attitudes of disrespect and violence towards women.

Source: The Global Media Monitoring Project (Data as of 2015); Report of the UN Secretary-General E/CN.6/2020/3

Entertainment

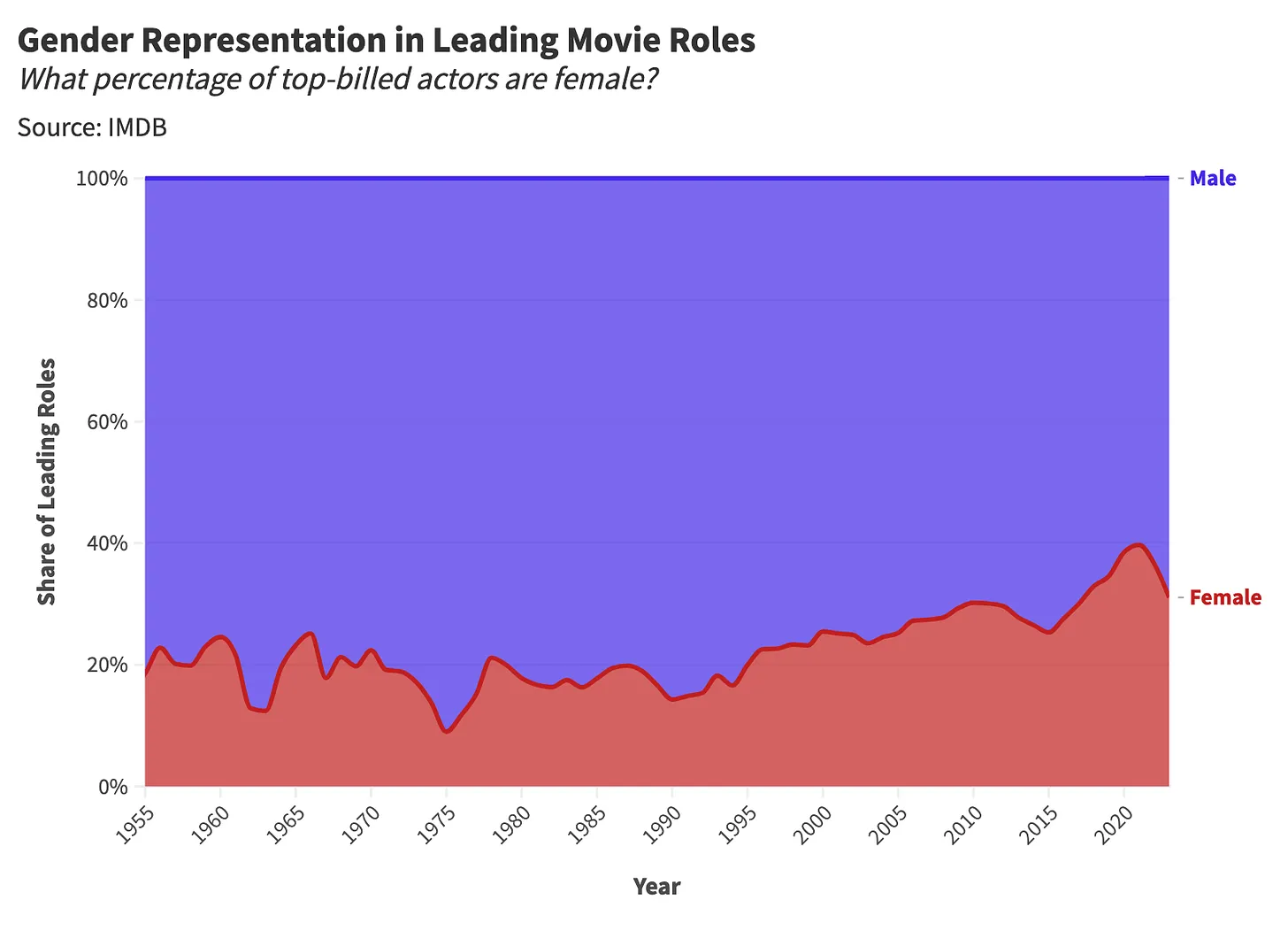

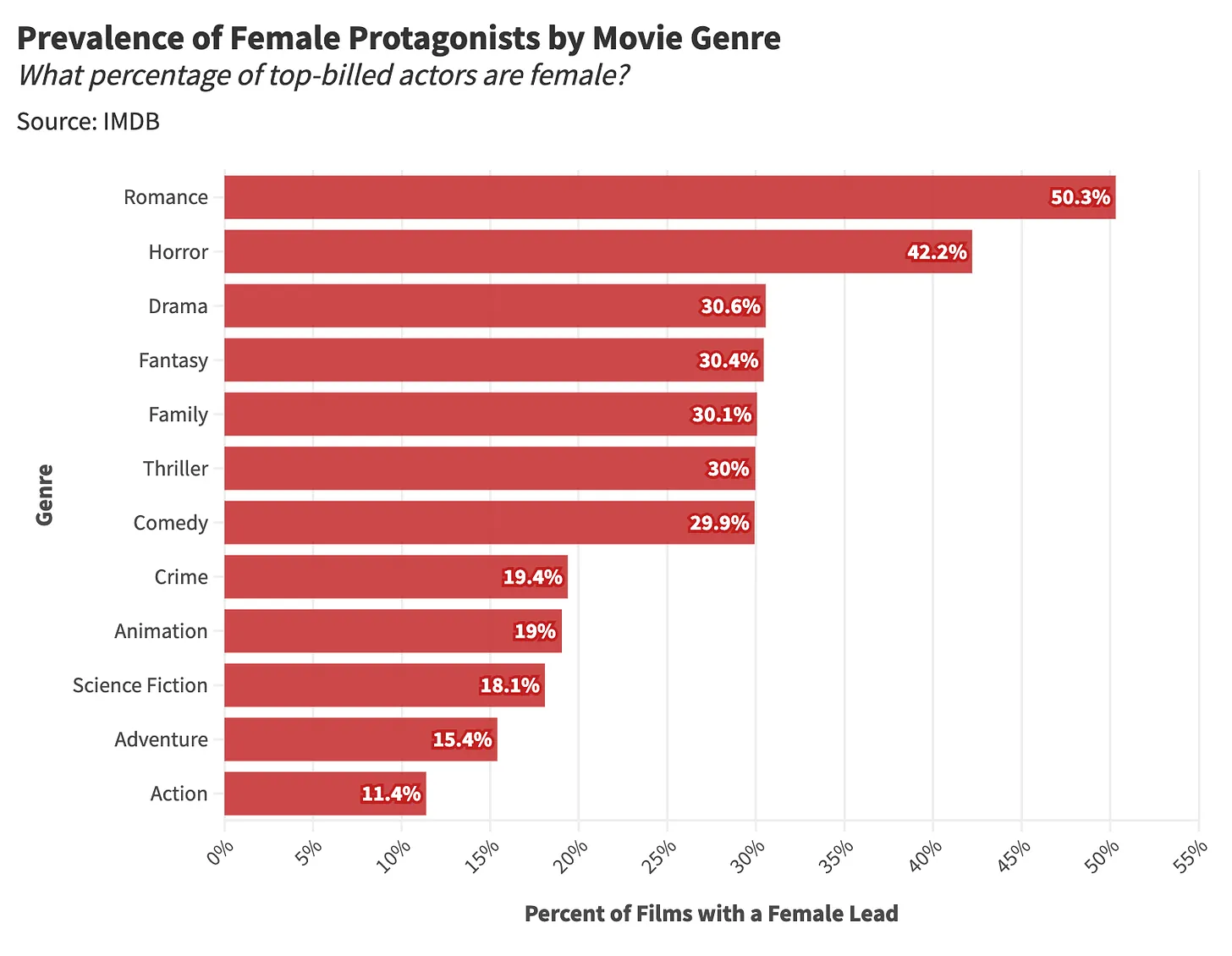

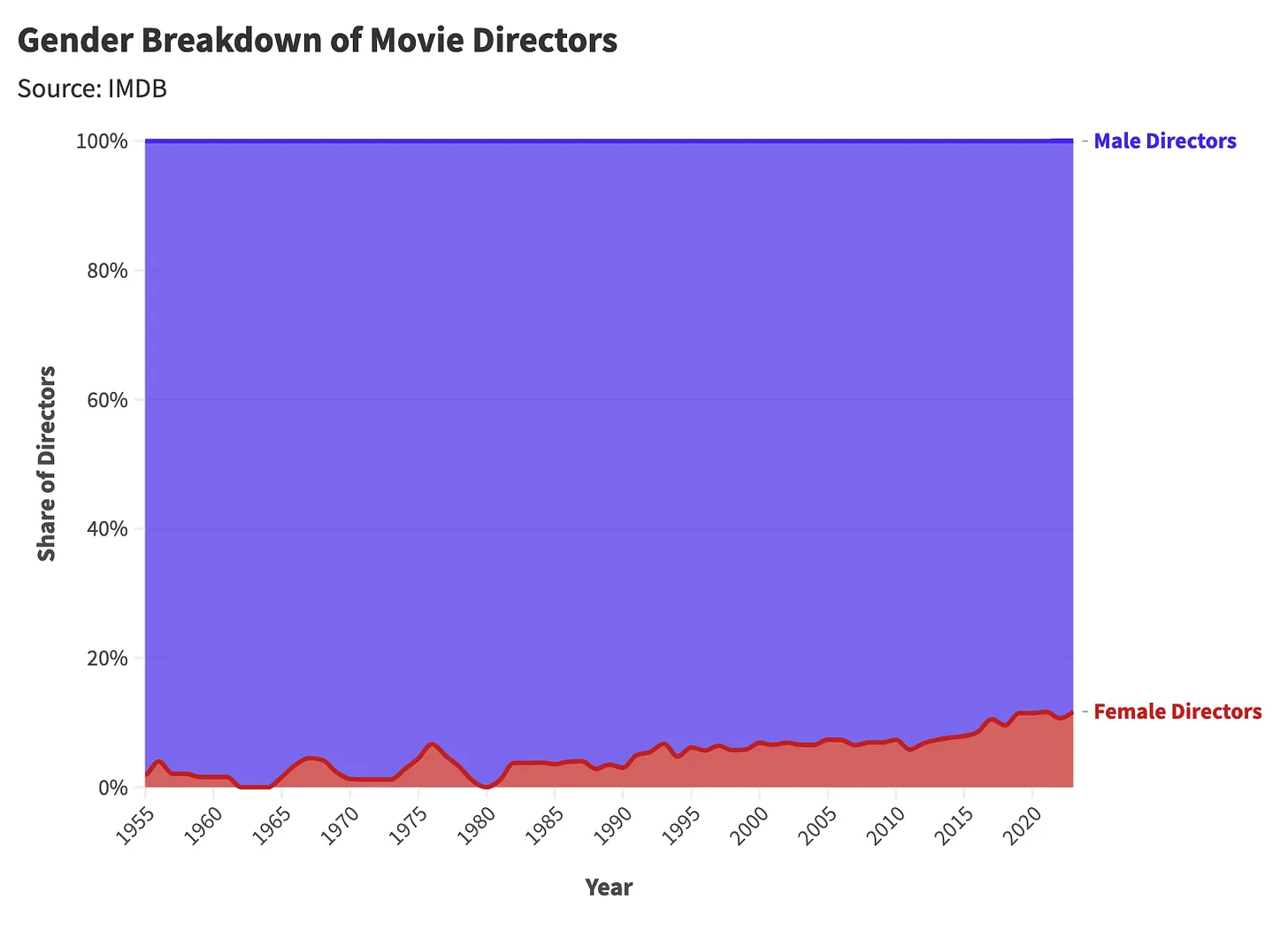

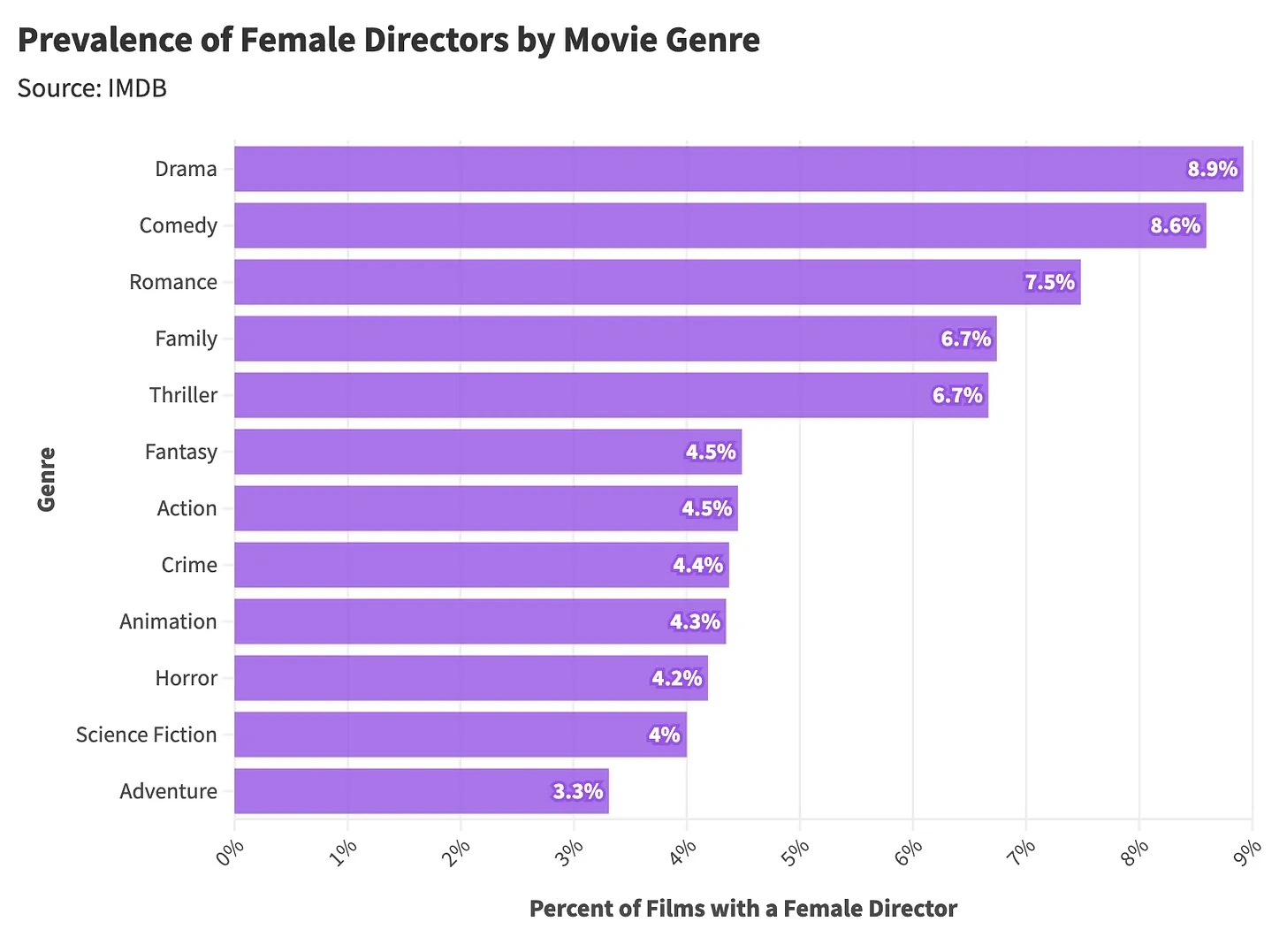

Like other forms of media, film and television have a powerful influence in shaping cultural perceptions and attitudes towards gender and are key to shifting the narrative for the gender equality agenda. Yet, an analysis of popular films across 11 countries found, for example, that 31 per cent of all speaking characters were women and that only 23 per cent featured a female protagonist—a number that closely mirrored the percentage of women filmmakers (21 per cent).

The gross underrepresentation of women in the film industry is also glaringly evident in critically acclaimed film awards: In the 92-year history of the Oscars, only five women have ever been nominated for the Best Director Award category; and one woman—Kathryn Bigelow—has ever won. And, Jane Campion remains the only woman director to have won the Cannes Film Festival’s top, most prestigious prize, the Palme d’Or, in its 72-year history. The only other women to have received the prize—but jointly—were actresses Adèle Exarchopoulos and Léa Seydoux with the movie's male director Abdellatif Kechiche. If a picture is worth a thousand words, the message is worth a million: If we are to shift stereotypical notions of gender and reflect women’s realities, we need more women in film, on-screen and off-screen.

Source: The Official Academy Awards® Database (Data as of 2020); A Brief History of the Palme d’Or, Cannes Film Festival (Data as of 2019)

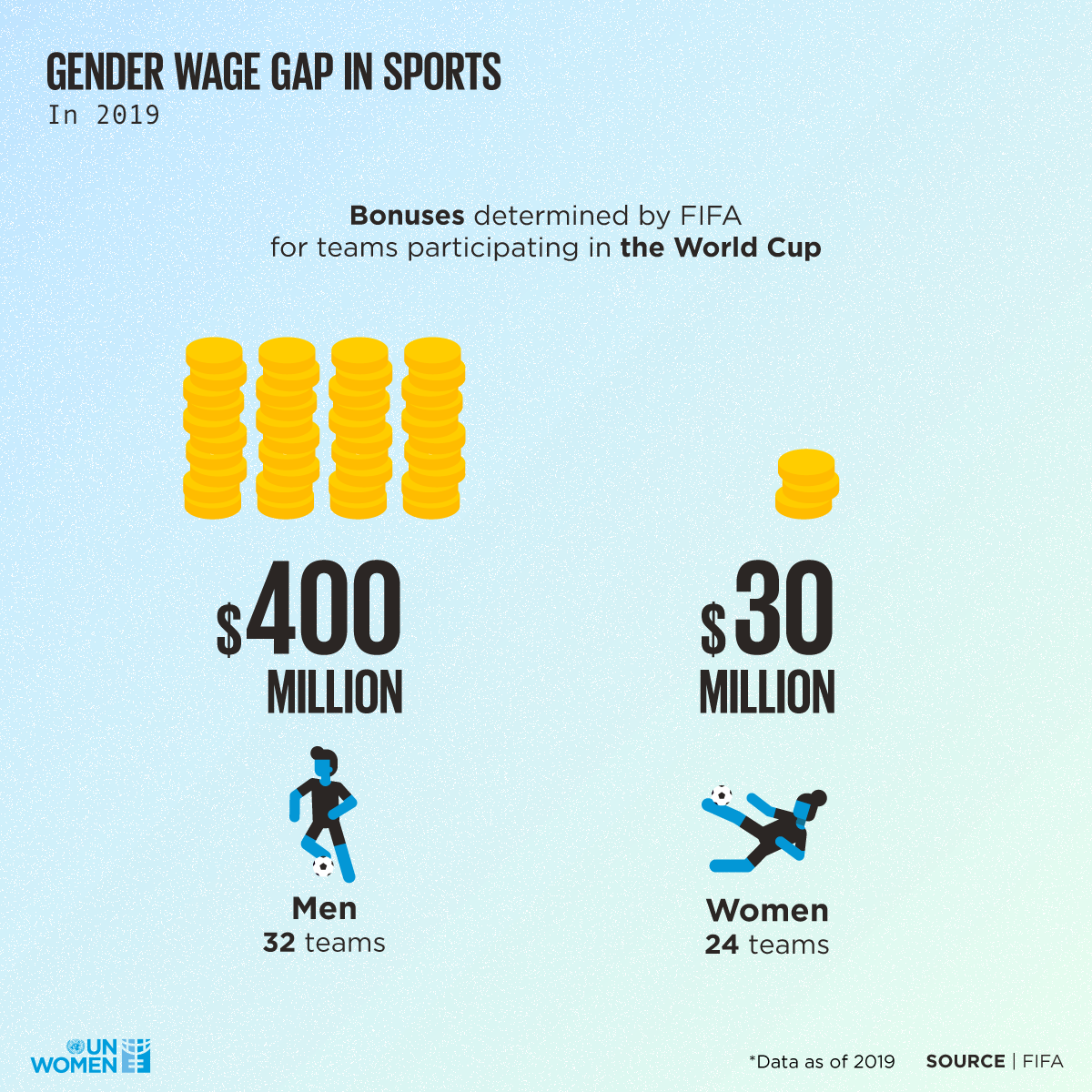

Sports has the power to inspire change and break gender stereotypes—and women have been doing just that decade after decade, showing that they are just as capable, resilient and strong as men physically, but also strategically, as leaders and game changers (Generation Equality pro tip: Watch Billie Jean King’s history-altering tennis match Battle of the Sexes).

Today, women are far more visible in sports than ever before: The Tokyo 2020 Olympics is projected to have close to equal representation of women and men competing for the first time in its history. For comparison, only 22 women (2.2 per cent) out of a total of 997 athletes competed in the modern Olympics for the first time in 1900. Women and men will compete in almost all sports categories with an exception: Rhythmic gymnastics and artistic swimming are women’s-only events and Greco-Roman wrestling is a men's-only event—although women can compete in freestyle wrestling.

Despite progress, women still continue to be excluded in certain sports in parts of the world and are paid far less than men in wages and prize money globally. UN Women is working to level the playing field for women and girls, including through partnerships with the International Olympic Committee, and UN Women Goodwill Ambassador and all-time top scorer of the FIFA Women’s World Cup Marta Vieira da Silva.

Source: The International Olympic Committee (Data as of 2020); FIFA (Data as of 2019)

Culinary arts

Despite women being prescribed stereotypical roles in the kitchen at home, the upper echelons of the restaurant industry have remained relatively closed to female chefs. As detailed in the documentary A Fine Line , women must often overcome active discrimination and navigate a culture that both glorifies masculinity and tacitly condones harassment. Paired with long, unpredictable and inflexible working hours, unfriendly family and childcare policies and lower salaries, women face enormous challenges when entering the restaurant business. The numbers match the story: Today, just under 4 per cent of chefs with three Michelin stars (the highest rating you can get) from the prominent restaurant guide are women.

Source: Michelin (Data as of 2019)

- ‘One Woman’ – The UN Women song

- UN Under-Secretary-General and UN Women Executive Director Sima Bahous

- Kirsi Madi, Deputy Executive Director for Resource Management, Sustainability and Partnerships

- Nyaradzayi Gumbonzvanda, Deputy Executive Director for Normative Support, UN System Coordination and Programme Results

- Guiding documents

- Report wrongdoing

- Programme implementation

- Career opportunities

- Application and recruitment process

- Meet our people

- Internship programme

- Procurement principles

- Gender-responsive procurement

- Doing business with UN Women

- How to become a UN Women vendor

- Contract templates and general conditions of contract

- Vendor protest procedure

- Facts and Figures

- Global norms and standards

- Women’s movements

- Parliaments and local governance

- Constitutions and legal reform

- Preguntas frecuentes

- Global Norms and Standards

- Macroeconomic policies and social protection

- Sustainable Development and Climate Change

- Rural women

- Employment and migration

- Facts and figures

- Creating safe public spaces

- Spotlight Initiative

- Essential services

- Focusing on prevention

- Research and data

- Other areas of work

- UNiTE campaign

- Conflict prevention and resolution

- Building and sustaining peace

- Young women in peace and security

- Rule of law: Justice and security

- Women, peace, and security in the work of the UN Security Council

- Preventing violent extremism and countering terrorism

- Planning and monitoring

- Humanitarian coordination

- Crisis response and recovery

- Disaster risk reduction

- Inclusive National Planning

- Public Sector Reform

- Tracking Investments

- Strengthening young women's leadership

- Economic empowerment and skills development for young women

- Action on ending violence against young women and girls

- Engaging boys and young men in gender equality

- Leadership and Participation

- National Planning

- Violence against Women

- Access to Justice

- Regional and country offices

- Regional and Country Offices

- Liaison offices

- 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development

- UN Women Global Innovation Coalition for Change

- Commission on the Status of Women

- Economic and Social Council

- General Assembly

- Security Council

- High-Level Political Forum on Sustainable Development

- Human Rights Council

- Climate change and the environment

- Other Intergovernmental Processes

- World Conferences on Women

- Global Coordination

- Regional and country coordination

- Promoting UN accountability

- Gender Mainstreaming

- Coordination resources

- System-wide strategy

- Focal Point for Women and Gender Focal Points

- Entity-specific implementation plans on gender parity

- Laws and policies

- Strategies and tools

- Reports and monitoring

- Training Centre services

- Publications

- Government partners

- National mechanisms

- Civil Society Advisory Groups

- Benefits of partnering with UN Women

- Business and philanthropic partners

- Goodwill Ambassadors

- National Committees

- UN Women Media Compact

- UN Women Alumni Association

- Editorial series

- Media contacts

- Annual report

- Progress of the world’s women

- SDG monitoring report

- World survey on the role of women in development

- Reprint permissions

- Secretariat

- 2023 sessions and other meetings

- 2022 sessions and other meetings

- 2021 sessions and other meetings

- 2020 sessions and other meetings

- 2019 sessions and other meetings

- 2018 sessions and other meetings

- 2017 sessions and other meetings

- 2016 sessions and other meetings

- 2015 sessions and other meetings

- Compendiums of decisions

- Reports of sessions

- Key Documents

- Brief history

- CSW snapshot

- Preparations

- Official Documents

- Official Meetings

- Side Events

- Session Outcomes

- CSW65 (2021)

- CSW64 / Beijing+25 (2020)

- CSW63 (2019)

- CSW62 (2018)

- CSW61 (2017)

- Member States

- Eligibility

- Registration

- Opportunities for NGOs to address the Commission

- Communications procedure

- Grant making

- Accompaniment and growth

- Results and impact

- Knowledge and learning

- Social innovation

- UN Trust Fund to End Violence against Women

- About Generation Equality

- Generation Equality Forum

- Action packs

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Feminist Perspectives on Sex and Gender

Feminism is said to be the movement to end women’s oppression (hooks 2000, 26). One possible way to understand ‘woman’ in this claim is to take it as a sex term: ‘woman’ picks out human females and being a human female depends on various biological and anatomical features (like genitalia). Historically many feminists have understood ‘woman’ differently: not as a sex term, but as a gender term that depends on social and cultural factors (like social position). In so doing, they distinguished sex (being female or male) from gender (being a woman or a man), although most ordinary language users appear to treat the two interchangeably. In feminist philosophy, this distinction has generated a lively debate. Central questions include: What does it mean for gender to be distinct from sex, if anything at all? How should we understand the claim that gender depends on social and/or cultural factors? What does it mean to be gendered woman, man, or genderqueer? This entry outlines and discusses distinctly feminist debates on sex and gender considering both historical and more contemporary positions.

1.1 Biological determinism

1.2 gender terminology, 2.1 gender socialisation, 2.2 gender as feminine and masculine personality, 2.3 gender as feminine and masculine sexuality, 3.1.1 particularity argument, 3.1.2 normativity argument, 3.2 is sex classification solely a matter of biology, 3.3 are sex and gender distinct, 3.4 is the sex/gender distinction useful, 4.1.1 gendered social series, 4.1.2 resemblance nominalism, 4.2.1 social subordination and gender, 4.2.2 gender uniessentialism, 4.2.3 gender as positionality, 5. beyond the binary, 6. conclusion, other internet resources, related entries, 1. the sex/gender distinction..

The terms ‘sex’ and ‘gender’ mean different things to different feminist theorists and neither are easy or straightforward to characterise. Sketching out some feminist history of the terms provides a helpful starting point.

Most people ordinarily seem to think that sex and gender are coextensive: women are human females, men are human males. Many feminists have historically disagreed and have endorsed the sex/ gender distinction. Provisionally: ‘sex’ denotes human females and males depending on biological features (chromosomes, sex organs, hormones and other physical features); ‘gender’ denotes women and men depending on social factors (social role, position, behaviour or identity). The main feminist motivation for making this distinction was to counter biological determinism or the view that biology is destiny.

A typical example of a biological determinist view is that of Geddes and Thompson who, in 1889, argued that social, psychological and behavioural traits were caused by metabolic state. Women supposedly conserve energy (being ‘anabolic’) and this makes them passive, conservative, sluggish, stable and uninterested in politics. Men expend their surplus energy (being ‘katabolic’) and this makes them eager, energetic, passionate, variable and, thereby, interested in political and social matters. These biological ‘facts’ about metabolic states were used not only to explain behavioural differences between women and men but also to justify what our social and political arrangements ought to be. More specifically, they were used to argue for withholding from women political rights accorded to men because (according to Geddes and Thompson) “what was decided among the prehistoric Protozoa cannot be annulled by Act of Parliament” (quoted from Moi 1999, 18). It would be inappropriate to grant women political rights, as they are simply not suited to have those rights; it would also be futile since women (due to their biology) would simply not be interested in exercising their political rights. To counter this kind of biological determinism, feminists have argued that behavioural and psychological differences have social, rather than biological, causes. For instance, Simone de Beauvoir famously claimed that one is not born, but rather becomes a woman, and that “social discrimination produces in women moral and intellectual effects so profound that they appear to be caused by nature” (Beauvoir 1972 [original 1949], 18; for more, see the entry on Simone de Beauvoir ). Commonly observed behavioural traits associated with women and men, then, are not caused by anatomy or chromosomes. Rather, they are culturally learned or acquired.

Although biological determinism of the kind endorsed by Geddes and Thompson is nowadays uncommon, the idea that behavioural and psychological differences between women and men have biological causes has not disappeared. In the 1970s, sex differences were used to argue that women should not become airline pilots since they will be hormonally unstable once a month and, therefore, unable to perform their duties as well as men (Rogers 1999, 11). More recently, differences in male and female brains have been said to explain behavioural differences; in particular, the anatomy of corpus callosum, a bundle of nerves that connects the right and left cerebral hemispheres, is thought to be responsible for various psychological and behavioural differences. For instance, in 1992, a Time magazine article surveyed then prominent biological explanations of differences between women and men claiming that women’s thicker corpus callosums could explain what ‘women’s intuition’ is based on and impair women’s ability to perform some specialised visual-spatial skills, like reading maps (Gorman 1992). Anne Fausto-Sterling has questioned the idea that differences in corpus callosums cause behavioural and psychological differences. First, the corpus callosum is a highly variable piece of anatomy; as a result, generalisations about its size, shape and thickness that hold for women and men in general should be viewed with caution. Second, differences in adult human corpus callosums are not found in infants; this may suggest that physical brain differences actually develop as responses to differential treatment. Third, given that visual-spatial skills (like map reading) can be improved by practice, even if women and men’s corpus callosums differ, this does not make the resulting behavioural differences immutable. (Fausto-Sterling 2000b, chapter 5).

In order to distinguish biological differences from social/psychological ones and to talk about the latter, feminists appropriated the term ‘gender’. Psychologists writing on transsexuality were the first to employ gender terminology in this sense. Until the 1960s, ‘gender’ was often used to refer to masculine and feminine words, like le and la in French. However, in order to explain why some people felt that they were ‘trapped in the wrong bodies’, the psychologist Robert Stoller (1968) began using the terms ‘sex’ to pick out biological traits and ‘gender’ to pick out the amount of femininity and masculinity a person exhibited. Although (by and large) a person’s sex and gender complemented each other, separating out these terms seemed to make theoretical sense allowing Stoller to explain the phenomenon of transsexuality: transsexuals’ sex and gender simply don’t match.

Along with psychologists like Stoller, feminists found it useful to distinguish sex and gender. This enabled them to argue that many differences between women and men were socially produced and, therefore, changeable. Gayle Rubin (for instance) uses the phrase ‘sex/gender system’ in order to describe “a set of arrangements by which the biological raw material of human sex and procreation is shaped by human, social intervention” (1975, 165). Rubin employed this system to articulate that “part of social life which is the locus of the oppression of women” (1975, 159) describing gender as the “socially imposed division of the sexes” (1975, 179). Rubin’s thought was that although biological differences are fixed, gender differences are the oppressive results of social interventions that dictate how women and men should behave. Women are oppressed as women and “by having to be women” (Rubin 1975, 204). However, since gender is social, it is thought to be mutable and alterable by political and social reform that would ultimately bring an end to women’s subordination. Feminism should aim to create a “genderless (though not sexless) society, in which one’s sexual anatomy is irrelevant to who one is, what one does, and with whom one makes love” (Rubin 1975, 204).

In some earlier interpretations, like Rubin’s, sex and gender were thought to complement one another. The slogan ‘Gender is the social interpretation of sex’ captures this view. Nicholson calls this ‘the coat-rack view’ of gender: our sexed bodies are like coat racks and “provide the site upon which gender [is] constructed” (1994, 81). Gender conceived of as masculinity and femininity is superimposed upon the ‘coat-rack’ of sex as each society imposes on sexed bodies their cultural conceptions of how males and females should behave. This socially constructs gender differences – or the amount of femininity/masculinity of a person – upon our sexed bodies. That is, according to this interpretation, all humans are either male or female; their sex is fixed. But cultures interpret sexed bodies differently and project different norms on those bodies thereby creating feminine and masculine persons. Distinguishing sex and gender, however, also enables the two to come apart: they are separable in that one can be sexed male and yet be gendered a woman, or vice versa (Haslanger 2000b; Stoljar 1995).

So, this group of feminist arguments against biological determinism suggested that gender differences result from cultural practices and social expectations. Nowadays it is more common to denote this by saying that gender is socially constructed. This means that genders (women and men) and gendered traits (like being nurturing or ambitious) are the “intended or unintended product[s] of a social practice” (Haslanger 1995, 97). But which social practices construct gender, what social construction is and what being of a certain gender amounts to are major feminist controversies. There is no consensus on these issues. (See the entry on intersections between analytic and continental feminism for more on different ways to understand gender.)

2. Gender as socially constructed

One way to interpret Beauvoir’s claim that one is not born but rather becomes a woman is to take it as a claim about gender socialisation: females become women through a process whereby they acquire feminine traits and learn feminine behaviour. Masculinity and femininity are thought to be products of nurture or how individuals are brought up. They are causally constructed (Haslanger 1995, 98): social forces either have a causal role in bringing gendered individuals into existence or (to some substantial sense) shape the way we are qua women and men. And the mechanism of construction is social learning. For instance, Kate Millett takes gender differences to have “essentially cultural, rather than biological bases” that result from differential treatment (1971, 28–9). For her, gender is “the sum total of the parents’, the peers’, and the culture’s notions of what is appropriate to each gender by way of temperament, character, interests, status, worth, gesture, and expression” (Millett 1971, 31). Feminine and masculine gender-norms, however, are problematic in that gendered behaviour conveniently fits with and reinforces women’s subordination so that women are socialised into subordinate social roles: they learn to be passive, ignorant, docile, emotional helpmeets for men (Millett 1971, 26). However, since these roles are simply learned, we can create more equal societies by ‘unlearning’ social roles. That is, feminists should aim to diminish the influence of socialisation.

Social learning theorists hold that a huge array of different influences socialise us as women and men. This being the case, it is extremely difficult to counter gender socialisation. For instance, parents often unconsciously treat their female and male children differently. When parents have been asked to describe their 24- hour old infants, they have done so using gender-stereotypic language: boys are describes as strong, alert and coordinated and girls as tiny, soft and delicate. Parents’ treatment of their infants further reflects these descriptions whether they are aware of this or not (Renzetti & Curran 1992, 32). Some socialisation is more overt: children are often dressed in gender stereotypical clothes and colours (boys are dressed in blue, girls in pink) and parents tend to buy their children gender stereotypical toys. They also (intentionally or not) tend to reinforce certain ‘appropriate’ behaviours. While the precise form of gender socialization has changed since the onset of second-wave feminism, even today girls are discouraged from playing sports like football or from playing ‘rough and tumble’ games and are more likely than boys to be given dolls or cooking toys to play with; boys are told not to ‘cry like a baby’ and are more likely to be given masculine toys like trucks and guns (for more, see Kimmel 2000, 122–126). [ 1 ]

According to social learning theorists, children are also influenced by what they observe in the world around them. This, again, makes countering gender socialisation difficult. For one, children’s books have portrayed males and females in blatantly stereotypical ways: for instance, males as adventurers and leaders, and females as helpers and followers. One way to address gender stereotyping in children’s books has been to portray females in independent roles and males as non-aggressive and nurturing (Renzetti & Curran 1992, 35). Some publishers have attempted an alternative approach by making their characters, for instance, gender-neutral animals or genderless imaginary creatures (like TV’s Teletubbies). However, parents reading books with gender-neutral or genderless characters often undermine the publishers’ efforts by reading them to their children in ways that depict the characters as either feminine or masculine. According to Renzetti and Curran, parents labelled the overwhelming majority of gender-neutral characters masculine whereas those characters that fit feminine gender stereotypes (for instance, by being helpful and caring) were labelled feminine (1992, 35). Socialising influences like these are still thought to send implicit messages regarding how females and males should act and are expected to act shaping us into feminine and masculine persons.

Nancy Chodorow (1978; 1995) has criticised social learning theory as too simplistic to explain gender differences (see also Deaux & Major 1990; Gatens 1996). Instead, she holds that gender is a matter of having feminine and masculine personalities that develop in early infancy as responses to prevalent parenting practices. In particular, gendered personalities develop because women tend to be the primary caretakers of small children. Chodorow holds that because mothers (or other prominent females) tend to care for infants, infant male and female psychic development differs. Crudely put: the mother-daughter relationship differs from the mother-son relationship because mothers are more likely to identify with their daughters than their sons. This unconsciously prompts the mother to encourage her son to psychologically individuate himself from her thereby prompting him to develop well defined and rigid ego boundaries. However, the mother unconsciously discourages the daughter from individuating herself thereby prompting the daughter to develop flexible and blurry ego boundaries. Childhood gender socialisation further builds on and reinforces these unconsciously developed ego boundaries finally producing feminine and masculine persons (1995, 202–206). This perspective has its roots in Freudian psychoanalytic theory, although Chodorow’s approach differs in many ways from Freud’s.

Gendered personalities are supposedly manifested in common gender stereotypical behaviour. Take emotional dependency. Women are stereotypically more emotional and emotionally dependent upon others around them, supposedly finding it difficult to distinguish their own interests and wellbeing from the interests and wellbeing of their children and partners. This is said to be because of their blurry and (somewhat) confused ego boundaries: women find it hard to distinguish their own needs from the needs of those around them because they cannot sufficiently individuate themselves from those close to them. By contrast, men are stereotypically emotionally detached, preferring a career where dispassionate and distanced thinking are virtues. These traits are said to result from men’s well-defined ego boundaries that enable them to prioritise their own needs and interests sometimes at the expense of others’ needs and interests.

Chodorow thinks that these gender differences should and can be changed. Feminine and masculine personalities play a crucial role in women’s oppression since they make females overly attentive to the needs of others and males emotionally deficient. In order to correct the situation, both male and female parents should be equally involved in parenting (Chodorow 1995, 214). This would help in ensuring that children develop sufficiently individuated senses of selves without becoming overly detached, which in turn helps to eradicate common gender stereotypical behaviours.

Catharine MacKinnon develops her theory of gender as a theory of sexuality. Very roughly: the social meaning of sex (gender) is created by sexual objectification of women whereby women are viewed and treated as objects for satisfying men’s desires (MacKinnon 1989). Masculinity is defined as sexual dominance, femininity as sexual submissiveness: genders are “created through the eroticization of dominance and submission. The man/woman difference and the dominance/submission dynamic define each other. This is the social meaning of sex” (MacKinnon 1989, 113). For MacKinnon, gender is constitutively constructed : in defining genders (or masculinity and femininity) we must make reference to social factors (see Haslanger 1995, 98). In particular, we must make reference to the position one occupies in the sexualised dominance/submission dynamic: men occupy the sexually dominant position, women the sexually submissive one. As a result, genders are by definition hierarchical and this hierarchy is fundamentally tied to sexualised power relations. The notion of ‘gender equality’, then, does not make sense to MacKinnon. If sexuality ceased to be a manifestation of dominance, hierarchical genders (that are defined in terms of sexuality) would cease to exist.