Language/Idioma:

Case studies.

Use these four case studies to test your knowledge of OA in the context of real-world patient scenarios, which span the content covered in the other eight modules.

Case Study #1

Q1. What are Betty’s risk factors for OA?

A. Gender B. Age C. Weight D. Occupation E. All of the above

Rationale (E) Female sex is associated with an increased risk of OA, especially OA of the hand, foot, and knee. Advancing age is by far the most well-known risk factor for OA. Betty’s weight is also a risk factor, even though her OA symptoms are currently only present in her hands; there is research showing that obesity can increase the risk of hand OA. Certain occupations that involve repetitive motion of a joint, like sewing, can worsen OA symptoms.

On examination, both of Betty’s hands appear normal (e.g., no deformities and no visible signs of inflammation); however, Betty reports stiffness and pain (lasting for ~15-20 minutes) when she first wakes up and after resting for prolonged periods. She has not missed any days from work, but admits the pain is significantly worse compared to a year ago. When asked, Betty states she is looking for pain relief and fears the arthritis “will spread” to her other joints.

Q2. What points of information should be shared with Betty?

A. Education about OA B. Weight loss counseling C. Sample hand exercises D. Offer a referral to Occupational Therapy E. All of the above

Rationale (E): Providing Betty with education about OA and explaining that it does not “spread” is a good place to start. It is important, however, to identify Betty’s risk factors and explain the importance of self-management strategies. While weight loss may not appear relevant to hand OA and could be daunting for a patient who is obese, education on the importance of weight loss, even a modest 5-10 pounds, can significantly improve mobility and function as well as reduce pain and may even help prevent OA in other joints such as her knees. You can encourage Betty to engage in healthy eating habits as well as hand exercises. One simple suggestion to increase mobility is that while Betty is watching TV, for example, she opens and closes her hands 5-10 times when a commercial is played. You can offer to submit a referral to an occupational therapist who can evaluate her for splinting, suggest additional exercises for hands, and recommend joint protection strategies in addition to assistive devices. If you feel that Betty can handle additional information, consider giving her a handout that describes resources and programs available for adults with OA to support physical activity, weight loss, managing pain, self-care, social support, and medical care.

Q3. What drug therapy poses the least risk for Betty?

A. Topical capsaicin B. Oral NSAID C. Acetaminophen D. Glucosamine with chondroitin

Rationale (C): Given Betty’s age as well as her history of hypertension and diabetes, an NSAID should be avoided as first-line therapy. Neither glucosamine nor chondroitin will treat her acute pain and the benefit of these agents in OA is unsubstantiated. Alternatively, APAP (< 3 grams per day) may be a safe and effective treatment option for Betty. While taking APAP, Betty should be counseled to avoid other APAP-containing products (e.g., cough and cold remedies or any product claiming to be “aspirin free”).

Case Study #2

John and his wife come in for a primary care visit following his hospital discharge. John is a 70-year-old man who is slightly overweight and has dyslipidemia, hypertension, and knee OA. He recently suffered a right cerebral vascular accident (CVA) due to atrial fibrillation that resulted in mild left hemiparesis. Prior to his stroke, he was prescribed a statin, ACE-inhibitor, diuretic, and calcium channel blocker.

In addition, John has new prescriptions for novel oral anticoagulant (NOAC) for secondary stroke prevention and an NSAID for knee pain, which was exacerbated during his post-CVA physical therapy sessions in the hospital. John has been mostly sedentary since he retired 5 years ago. In fact, other than physical rehabilitation in the hospital, he has not been physically active in years. He will begin outpatient physical therapy tomorrow for post-CVA rehabilitation.

Q1. What should be your primary concern?

A. Assessing whether John is able to take care of himself at home B. Addressing a drug interaction C. Submitting a referral for occupational therapy D. Recommending community-based physical activity programs

Rationale (B): Given the significance of the drug interaction between the NSAID and NOAC, this should be your primary concern. While an oral NSAID may provide pain relief for his knee OA, John’s age, co-morbidities, and concomitant drug therapy makes an oral NSAID relatively contraindicated. You learn that a trial of acetaminophen at a dose of 3 grams per day was not helpful in relieving Johns’ increased knee pain, so you could consider a topical NSAID. While these drugs carry the same black box warnings as oral NSAIDs, research has shown that the drug interactions with the NOAC, ACE-inhibitor, and diuretic are reduced; thereby, reducing the risk of bleeding and acute renal failure.

Q2. What non-pharmacologic treatment modalities should be recommended?

A. Weight loss B. Reduce periods of physical inactivity C. Community-based physical activity programs D. All of the above

Rationale (D): It would be important to encourage John to lose even a minimal amount of weight through improved diet and increased physical activity. Reducing his periods of inactivity will also help with his knee OA pain, as sustained periods of rest can worsen OA symptoms; therefore, promoting simple activity (e.g., every 20-30 minutes) may reduce OA pain and stiffness. You can also encourage him to discuss specific exercises with his outpatient physical therapist that will target the OA in his knee; the PT can give him exercises to do on his own at home. There are also many community programs designed specifically for patients with OA that John could transition to when his PT sessions are complete.

Case wrap up and recommendations:

Now that John is home, you will likely need to help in the coordination of care by advising continued therapy with physical therapy or cardiac rehabilitation and helping him find ways of staying physically active after therapy concludes. You can also provide ongoing coaching on simple ways to increase activity around the home and to manage his weight through his diet. It might be helpful to refer him to a registered dietitian. Because of the impact of his stroke, John is at risk for falls; therefore, promotion of safety is paramount. You can encourage John that his participation in physical activity will not only help improve his OA symptoms and hypertension but will also help him strengthen his lower body to prevent falls which could cause further limitations and disability. Periodic reassessment should also take place to evaluate his current non-drug and drug therapy regimens.

Case Study #3

Q1. What are Emma’s risk factors for developing OA?

A. Having had a knee injury B. Being female C. Being overweight D. All of the above

Rationale (D): Emma has a combination of modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors for developing OA. The non-modifiable risk factors include being female and having a prior injury. Emma’s modifiable risk factor is being overweight.

Q2. What strategies would best help Emma reduce her pain and slow the progression of OA?

A. Lose weight and increase physical activity B. Oral or topical NSAIDs C. Intraarticular corticosteroid injection D. Nothing; knee pain is inevitable with aging, and she should learn to live with it.

Rationale (A): In Emma’s case, losing weight is going to help reduce her OA symptoms significantly. A 10-pound weight loss can reduce the amount of knee joint loading by 40 pounds. Increasing physical activity is definitely recommended, too; it reduces pain, strengthens muscles, helps prevent the progression of OA and is an important part of a weight loss program. Emma could use acetaminophen when she has increased pain, but she should be cautioned to avoid cold or cough remedies also containing acetaminophen. Emma can also be encouraged that OA pain is not inevitable despite her age and prior sports history and that with proper management, she can return to a pain-free lifestyle.

Q3. What might it look like to use the 5 As model with Emma to discuss her weight? The 5 As model guides you to: Ask→ Assess→ Advise→ Agree→ Assist.

A. You ask Emma to increase her physical activity because you determined that she is obese based on her BMI and because she reports being mostly sedentary on the assessment form. You recommend that she perform moderate physical activity 150 minutes per week, and you set this as her SMART goal, to which she agrees. You recommend gyms in the area that she could join. B. You ask Emma if she would like to be a healthier weight. You suggest that increased physical activity and nutrition counseling help many patients, and advise her to do both. You refer her to a physical therapist who can help her with her knee pain and develop an appropriate physical activity program. You also refer her to a registered dietitian. C. You ask Emma if she has concerns about her weight, and she says she does and that she would like to be a healthier weight. You examine her chart again and note that she commonly eats fast foot and is mostly sedentary. You suggest increased physical activity and nutrition counseling, and ask her which of these modifications is possibly achievable for her now. Emma thinks diet change is possible, so you help her set a SMART goal to improve her diet and refer her to a registered dietitian. D. You ask Emma if it would be alright if you discussed her weight, and she states that she would like to learn how to achieve a healthy weight. Based on information you learned from her chart and her assessment form that she completed, you tell her she needs to be more physically active and to change her diet to lose weight. You advise her to keep a food journal, and you tell her that diet change is an achievable SMART goal for her. You refer her to a registered dietitian.

Rationale (C): Ask : Ask if Emma would be willing to talk to you about her weight. Does she have concerns about her weight? If she answers yes to these questions, then proceed. Assess : You notice in Emma’s chart that her weight gain really escalated after the birth of her second child a couple of years ago, and from her answers on the patient information form, you see that she is getting less than 150 minutes of moderate to strenuous exercise per week. Ask Emma about other contributing factors such as diet, sleep, and depression. Advise : You can tell that Emma knows the risks of being overweight on her cardiovascular health and her chance of developing diabetes. Tell her that she has two major risk factors for osteoarthritis (OA): excess weight and previous knee injury and that her knee pain could be from OA. Let her know that she is 2-4 times more likely to develop OA because of her previous knee injury. It could also help Emma to hear that every pound of weight she loses, would mean 4 pounds less of pressure on her knee joints. Offer Emma some options for weight loss strategies (increased physical activity, nutrition counseling, food journaling, etc) and see which she thinks is most realistic right now. Agree : If Emma is willing and ready, help her set 1-2 SMART goals (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic, Time-bound) around increasing her physical activity and/or addressing her diet or sleep habits. Assist : If appropriate, ask Emma if she would like a referral to see a nutrition counselor. It might also be beneficial for Emma to see a Physical Therapist or Sports Medicine professional to get help developing a neuromuscular training program that includes strengthening, balance, and plyometric exercises; this will help her prevent future injury to her knees. These professionals could also fit her for a knee brace if appropriate. You can ask Emma if she needs any community resources for fitness programs. Finally, make a plan to follow-up with Emma. If your practice has a chronic care manager, schedule her to have a series of phone calls with the case manager. Offer to see her back for a follow-up appointment with you in 3-6 months.

Case Study #4

Q1. What additional evaluation is needed to confirm the etiology of her knee pain?

A. Bilateral standing knee x-rays B. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate C. Serum uric acid level D. MRI of the right knee E. None of the above

Rationale (E): The diagnosis of OA is generally a clinical one and can be made in this patient with very typical history without additional lab or imaging studies.

Maria was diagnosed with type II diabetes 2 years ago and had a HbA1c of 8% last month. She also has hypertension, high cholesterol, chronic kidney disease, and mild COPD from remote smoking. Her medications include metformin, glyburide, pravastatin, losartan, and an inhaler. She previously took acetaminophen but stopped as it was not helping her joint pain.

Q2. What intervention is most likely to improve her knee pain with minimal risk?

A. Oral or topical NSAIDs B. Intra-articular corticosteroid injection C. Increased physical activity D. Initiate scheduled acetaminophen

Rationale (C): Physical activity is the most important intervention in this case, not only because it is the most likely to lead to substantial improvements in knee pain and function (IDEA Trial1), but also because it can improve management of her other comorbid conditions. Topical NSAIDs might be a useful adjunct, but additional information about her CKD would be needed; oral NSAIDs are likely contraindicated given her age and comorbidities. Intra-articular corticosteroid could provide temporary relief for the right knee, but not the left, and has the potential to increase her blood sugar. She has already tried acetaminophen in therapeutic doses without help, and given the minimal efficacy of this agent, additional trials are unlikely to be of benefit.

On examination, Maria’s resting blood pressure is 150/95, heart rate is 90, and respiratory rate is 14. Her BMI is 32 kg/m2. She is in no acute distress, and examination of her head, neck, eyes, and ENT is unremarkable. She has an intermittent expiratory wheeze, but normal work of breathing. Her cardiovascular exam is unremarkable, as is her GI evaluation. There is no edema in her extremities. Her musculoskeletal examination demonstrates scattered non-painful Heberden’s nodes, mild thumb base squaring, but otherwise normal hands, wrists, elbows, and shoulders. Hip range of motion is preserved, there is no sacroiliac or trochanteric tenderness. She endorses tenderness to palpation of the medial joint lines of both knees, worse on the right. There is a trace effusion of the right knee, none on the left. She has full ROM of both knees but endorses some stiffness; crepitus is noted on the right. The ankles and feet are unremarkable. She does not have diffuse muscular tenderness.

Q3. For which of her conditions would increased physical activity be beneficial?

A. Symptomatic osteoarthritis B. Type II diabetes C. Chronic kidney disease D. COPD E. All of the above

Rationale (E): Physical activity is a mainstay of management of all of these conditions and is the most important recommendation for management of her osteoarthritis.

Case wrap up and recommendations

Increased physical activity is recommended to the patient, recognizing that while physical activity is likely to benefit many of this patient’s chronic medical comorbidities, she may experience difficulty in engaging in increased activity due to these conditions. For example, knee pain or shortness of breath may limit walking endurance when walking is recommended for improved diabetes management. It is essential to inventory the comorbid conditions that may impact a patient’s ability to follow physical activity recommendations and to tailor those recommendations accordingly. In this case, a program of aquatic therapy, supervised physiotherapy, or pulmonary rehabilitation could assist with getting started, followed by a graded land-based program, graded walking program, or group activity class (based on preferences and local resources). The key is to begin slowly with manageable recommendations (i.e., not to recommend 150 minutes per week at the first visit) and to make incremental gains up to a goal agreed upon by both the provider and the patient, recognizing that any increase in physical activity is likely to provide wide-ranging benefits. Additional medical management and adjunctive therapies can still be used, with the aim of assisting the patient to reach her physical activity goals while minimizing symptoms.

- Messier SP, Mihalko SL, Legault C, et al. Effects of intensive diet and exercise on knee joint loads, inflammation, and clinical outcomes among overweight and obese adults with knee osteoarthritis: the IDEA randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;310(12):1263-1273.

- Remote Access

- Save figures into PowerPoint

- Download tables as PDFs

Chapter 27-1: Approach to the Patient with Joint Pain - Case 1

Adam S. Cifu

- Download Chapter PDF

Disclaimer: These citations have been automatically generated based on the information we have and it may not be 100% accurate. Please consult the latest official manual style if you have any questions regarding the format accuracy.

Download citation file:

- Search Book

Jump to a Section

Chief complaint, constructing a differential diagnosis.

- RANKING THE DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

- MAKING A DIAGNOSIS

- CASE RESOLUTION

- Full Chapter

- Supplementary Content

Mrs. K is a 75-year-old woman who complains of a painful left knee.

Figure 27-1.

Diagnostic approach: joint pain.

The causes of joint pain range from common to rare and from bothersome to life-threatening. Even the most benign causes of joint pain can lead to serious disability. The evaluation of a patient with joint pain calls for a detailed history and physical exam (often focusing on extra-articular findings) and occasionally the analysis of joint fluid, serologies, and radiologic tests.

The differential diagnosis of joint pain can be framed with the use of 3 pivotal questions. First, is a single joint or are multiple joints involved (is the joint pain monoarticular or polyarticular)? If the pain involves just 1 joint, the next question is, is the pain monoarticular or extra-articular? Although this distinction may seem obvious, abnormalities of periarticular structures can mimic articular disease. Finally, are the involved joints inflamed or not? Further down the differential, the acuity of the pain may also be important.

Figure 27-1 shows a useful algorithm organized according to these pivotal points. Because periarticular joint pain is almost always monoarticular, the first pivotal point differentiates monoarticular from polyarticular pain. Periarticular syndromes are discussed briefly at the end of the chapter.

The differential diagnosis below is organized by these 3 pivotal points as well. When considering both the algorithm and the differential diagnosis, recognize that all of the monoarticular arthritides can present in a polyarticular distribution, and classically polyarticular diseases may occasionally only affect a single joint. Thus, this organization is useful to organize your thinking but should never be used to exclude diagnoses from consideration.

Monoarticular arthritis

Inflammatory

Nongonococcal septic arthritis

Gonococcal arthritis

Lyme disease

Crystalline

Monosodium urate (gout)

Calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate deposition disease (CPPD or pseudogout)

Noninflammatory

Osteoarthritis (OA)

Avascular necrosis

Polyarticular arthritis

Rheumatologic

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA)

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

Psoriatic arthritis

Other rheumatic diseases

Bacterial endocarditis

Hepatitis B

Postinfectious

Rheumatic fever

Noninflammatory: OA

Mrs. K’s symptoms started after she stepped down from a bus with unusual force. The pain became intolerable within about 6 hours of onset and has been present for 3 days now. She otherwise feels well. She reports no fevers, chills, dietary changes, or sick contacts.

Get Free Access Through Your Institution

Pop-up div successfully displayed.

This div only appears when the trigger link is hovered over. Otherwise it is hidden from view.

Please Wait

- Case Report

- Open access

- Published: 16 September 2008

A woman living with osteoarthritis: A case report

- Jane C Richardson 1 ,

- Christian D Mallen 1 , 2 &

- Helen S Burrell 1

Cases Journal volume 1 , Article number: 153 ( 2008 ) Cite this article

23k Accesses

Metrics details

Osteoarthritis is a common condition that is typically associated with older adults. Other causes of osteoarthritis, such as those cases resulting from childhood Perthes disease, can affect younger people and frequently have a major impact on the lives of those affected. This case report describes the experiences of one patient with osteoarthritis, using examples of her poetry to illustrate her social, psychological and emotional transformation.

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common joint disease and one of the most widespread of all chronic conditions managed in general practice. Whilst the prevalence of OA increases with age, a significant minority of adults experience symptoms earlier in life. Most cases of osteoarthritis are not extraordinary, yet the individual experiences of those affected provide a unique opportunity for health care practitioners and researchers to more fully understand the impact that common conditions have on their patients.

This case report was triggered by a patient (HB) wanting to tell her story. The importance of narrative in medicine is increasingly being recognised as a powerful tool that can strengthen clinical practice and help to create an alliance with patients. This alternative case report, written by a researcher (JCR), a general practitioner (CDM) and a patient (HB), presents a fairly typical case of a younger adult with osteoarthritis. However, rather than presenting laboratory results or X-ray findings, we use Helen's poems to highlight her experiences and her journey with osteoarthritis.

Case presentation

Helen is 46 years old and has generalised osteoarthritis. Her hips and hands are the most severely affected joints. Helen's health problems started at the age of 11, following a fall on a cross-country run. She consulted her general practitioner and the accident unit multiple times with increasing levels of pain and disability before she was eventually diagnosed with Perthes disease, a diagnosis that has had a huge impact on her subsequent life. Over the years Helen has tried the full range of pain medications. A review of her past prescriptions reveals trials of over 15 different analgesics and anti-inflammatory drugs, covering the full range of the analgesic ladder. Her current medication, oxycodone, has so far been the best choice, optimising pain relief whilst minimising side effects. Helen continues to be under the care of local orthopaedic surgeons, who are contemplating further revisions to her failed total hip replacement. Helen remains independent and self-caring despite deterioration in her levels of pain and physical functioning.

Helen trained as a radiographer, but following the failure of a hip replacement she became a wheelchair user, which was not felt to be compatible with her job. This loss has had significant impact on Helen's identity: she describes it as being ' picked up from one life, where I could focus on me and what I wanted to happen, and put in another, where someone else was in control '. The issues of identity and social roles are key for Helen, in knowing how to define herself – 'A m I disabled? a woman? a disabled woman? a carer ?' – and in the huge loss of identity caused by loss of her job, associated financial security and her increasing disabilities. This meant radical changes to her social life, independence, choices, freedom of movement, interests and hobbies.

The nature of Helen's condition does not mean she has necessarily lost all other social roles. Helen's parents live close to her and suffer from a number of physical and mental health conditions. For Helen, being her parents' main carer is a source of positive identity and pride, although it also means she can be called to provide physical or emotional help at any time during the day or night. Her father's illness also meant that Helen took on some of his caring responsibilities, in looking after her elderly aunt who had dementia.

Relationships and friendships have been very important to Helen and have been affected by her condition. She had been engaged at age 21, shortly before a period of hospitalisation. The relationship ended, she felt, because of her depression during this period and her fiancé's lack of experience of dealing with such a situation. She describes the problems with actually meeting people with whom to have a relationship, but also the dilemma and difficulty of attempting to " build an equal partnership, when somebody does have to take on a carer's role ." She also describes conflict in relationships with people who had had disabilities since birth, both from their perspective, and from expectations of other people who thought she 'should' have a relationship with a non-disabled person.

Helen describes the process of learning " to become disabled ." An event she found helpful in this process was a disability awareness training course, because, " you're put into this situation but you don't get given a tablet to make you be disabled, ...to understand being disabled and impaired and 'all the rest of it"." This enabled her to write her own disability awareness course, including issues that were important to her as a woman and as a person who had acquired her disabilities.

Helen's relationship with her GP (CDM) is important to her, particularly as he is also her parents' GP and therefore has an understanding of the context in which she is managing her disability. She also feels strongly about the benefits of having a relationship with her GP in which she is seen as a person and is able to " be herself ", without being concerned that she is seen as a problem or that people are worrying about her.

We have presented a case of a woman with osteoarthritis secondary to Perthes disease in childhood. We have described her emotional, social and psychological transformation using her poetry to illustrate different life experiences. The notion of biographical disruption[ 1 ] can be used to describe the identity changes experienced by Helen. This 'breaking down' of one's life is eloquently described by Arthur Frank, a medical sociologist who has himself experienced critical illness: " What happens when my body breaks down happens not just to that body but also to my life, which is lived in that body. When the body breaks down, so does the life. Even when medicine can fix the body, that doesn't always put the life back together again ." [ 2 ] One response to biographical disruption is to attempt to repair the narrative of one's life[ 3 ]. Creativity, through poetry, writing or art, can be seen as one way of trying to make sense of this disruption. This type of creativity may be actively encouraged as part of a healing process [ 4 – 6 ], although Helen's poems were originally written solely for and by herself.

This is not a traditional case report, yet we believe that our approach can be equally as informative, by allowing doctors and researchers to more fully understand the impact a disease has on all aspects of their patient's lives.

Patient's perspective

Where have I gone?

Where's the woman who weighed less than 9 stone?

Who wore a dress size 12 and didn't need to wear shapeless clothes or jogging suits?

Who had shaped and tidy eyebrows that would complement her latest hair colour and style?

Whose painted nails, with manicured hands and feet, were perfect for holidays in the sun?

Where's the woman who had a vocation not just a job, but who exists on benefits, a step away from poverty?

Where's the woman who owned her own home that gave her safety and privacy, it was her pride and joy?"

Where's the woman whose hobbies include travel, gardening, decorating, furniture restoring, sewing, reading and studying at home?

Here I am and life before my impairment has gone, the only thing I can do is hold a pen with a special grip and writing is agony .

Where has she gone?

WHERE HAVE I GONE?

Do you see me?

How can you ever know me, when all you see is my chair?

My limitations are all you see and you say they complicate your life .

Will you ever see the deep pools of love in my eyes for you?

When you half close yours with pity and turn away from me .

The beating of my heart in expectation of your closeness is

quickly cooled by your fleeting hug or, worse, patting my shoulder .

I wait in anticipation remembering the taste and softness of

your kiss, you offer me a warm 'peck' on the cheek .

I smell your aftershave ... you say I smell clean!

I remember running my fingers through your hair ,

Ripping buttons off your shirt but that's difficult when you

stand behind me pushing my chair, we can't even hold hands anymore .

The power of my emotions makes me feel strong ,

Then I catch that pitying look in your eye ,

They die in my heart .

I do not speak, my smile fills my face but you will never know ...

You'll never see the real woman who is me

Who sits and is seen by the world framed by a wheelchair

Cut off emotionally just because I cannot stand or walk .

Thank you to those who take the time to listen to difficult and unclear speech, for you help us to know that if we persevere we can be understood

Thank you to those who walk with us in public places, ignoring stares and whispers from strangers, for in your friendship we find enjoyment, laughter and happiness

Thank you for never asking us to 'hurry up', but even more special is you don't snatch our tasks from us or offer 'Care' in such a way as to make us feel that we are still children, with no control and respect

Thank you for standing beside us when we enter new experiences and try new adventures

Though our success may be outweighed by our failure, the experience will stay with us forever and there will be many occasions when we surprise ourselves and maybe even you!

Thank you for asking for our help and expertise ,

As self-confidence and awareness come from being needed by you and others

Thank you for giving us respect

You acknowledge our value as experts in our fields and that we require to live with equality in society

We shouldn't have to ask or have laws to enforce it or remind you

Thank you for assuring us that the things that make us individuals are not our medical impairments, as everyone has those and they don't define ONE'S SELF, it's people's attitudes that create barriers that exclude us from you .

Treat us as we treat you .

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Bury M: Chronic illness as biographical disruption. Sociology of Health & Illness. 1982, 4: 167-182. 10.1111/1467-9566.ep11339939.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Frank AW: At the will of the body. 1992, Houghton Mifflin

Google Scholar

Frank AW: The Wounded Storyteller. Explore (NY). 2005, Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1 (2): 142-143.

http://www.lapidus.org.uk : aims to promote the use of creative writing for health and wellbeing.

Sampson F: The Healing Word. The Poetry Society. 1999

Hatem D, Rider EA: Sharing stories: narrative medicine in an evidence-based world. Patient Educ Couns. 2004, 54 (3): 251-253.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Arthritis Research Campaign National Primary Care Centre, Keele University, Keele, Staffs, ST5 5BG, England

Jane C Richardson, Christian D Mallen & Helen S Burrell

Kingsbridge Medical Practice, Kingsbridge Avenue, Clayton, Newcastle-under-Lyme, Staffordshire, ST5 3BR, England

Christian D Mallen

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jane C Richardson .

Additional information

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

"JCR interviewed HSB and wrote the article based on the interviews. CDM wrote the medical aspects of the article and helped with the drafting of the article. HSB wrote the patient perspective section. HSB and CDM helped revise the manuscript".

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Richardson, J.C., Mallen, C.D. & Burrell, H.S. A woman living with osteoarthritis: A case report. Cases Journal 1 , 153 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1186/1757-1626-1-153

Download citation

Received : 12 August 2008

Accepted : 16 September 2008

Published : 16 September 2008

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/1757-1626-1-153

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Osteoarthritis

- Disable Woman

- Perthes Disease

- Biographical Disruption

Cases Journal

ISSN: 1757-1626

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Sacroiliac joint dysfunction: a case study

Affiliation.

- 1 US Army, Nurse Corps, Kailua, HI, USA.

- PMID: 21422895

- DOI: 10.1097/NOR.0b013e31820f513e

Pain is a widespread issue in the United States. Nine of 10 Americans regularly suffer from pain, and nearly every person will experience low back pain at one point in their lives. Undertreated or unrelieved pain costs more than $60 billion a year from decreased productivity, lost income, and medical expenses. The ability to diagnose and provide appropriate medical treatment is imperative. This case study examines a 23-year-old Active Duty woman who is preparing to be involuntarily released from military duty for an easily correctable medical condition. She has complained of chronic low back pain that radiates into her hip and down her leg since experiencing a work-related injury. She has been seen by numerous providers for the previous 11 months before being referred to the chronic pain clinic. Upon the first appointment to the chronic pain clinic, she has been diagnosed with sacroiliac joint dysfunction. This case study will demonstrate the importance of a quality lower back pain assessment.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- [Sacroiliac joint dysfunction presented with acute low back pain: three case reports]. Hamauchi S, Morimoto D, Isu T, Sugawara A, Kim K, Shimoda Y, Motegi H, Matsumoto R, Isobe M. Hamauchi S, et al. No Shinkei Geka. 2010 Jul;38(7):655-61. No Shinkei Geka. 2010. PMID: 20628193 Japanese.

- Stabilization of the sacroiliac joint. Shaffrey CI, Smith JS. Shaffrey CI, et al. Neurosurg Focus. 2013 Jul;35(2 Suppl):Editorial. doi: 10.3171/2013.V2.FOCUS13273. Neurosurg Focus. 2013. PMID: 23829837

- Impairment-based examination and disability management of an elderly woman with sacroiliac region pain. Godges JJ, Varnum DR, Sanders KM. Godges JJ, et al. Phys Ther. 2002 Aug;82(8):812-21. Phys Ther. 2002. PMID: 12147010

- The sacroiliac joint: an underappreciated pain generator. Daum WJ. Daum WJ. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 1995 Jun;24(6):475-8. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 1995. PMID: 7670870 Review.

- 13. Sacroiliac joint pain. Vanelderen P, Szadek K, Cohen SP, De Witte J, Lataster A, Patijn J, Mekhail N, van Kleef M, Van Zundert J. Vanelderen P, et al. Pain Pract. 2010 Sep-Oct;10(5):470-8. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2010.00394.x. Pain Pract. 2010. PMID: 20667026 Review.

- Biomechanics of the Sacroiliac Joint: Surgical Treatments. Joukar A, Kiapour A, Elgafy H, Erbulut DU, Agarwal AK, Goel VK. Joukar A, et al. Int J Spine Surg. 2020 Jun 30;14(3):355-367. doi: 10.14444/7047. eCollection 2020 Jun. Int J Spine Surg. 2020. PMID: 32699758 Free PMC article.

- Comparison of the costs of nonoperative care to minimally invasive surgery for sacroiliac joint disruption and degenerative sacroiliitis in a United States commercial payer population: potential economic implications of a new minimally invasive technology. Ackerman SJ, Polly DW Jr, Knight T, Schneider K, Holt T, Cummings J Jr. Ackerman SJ, et al. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2014 May 24;6:283-96. doi: 10.2147/CEOR.S63757. eCollection 2014. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2014. PMID: 24904218 Free PMC article.

- Comparison of the costs of nonoperative care to minimally invasive surgery for sacroiliac joint disruption and degenerative sacroiliitis in a United States Medicare population: potential economic implications of a new minimally-invasive technology. Ackerman SJ, Polly DW Jr, Knight T, Schneider K, Holt T, Cummings J. Ackerman SJ, et al. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2013 Nov 20;5:575-87. doi: 10.2147/CEOR.S52967. eCollection 2013. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2013. PMID: 24348055 Free PMC article.

- Minimally invasive sacroiliac joint fusion: one-year outcomes in 40 patients. Sachs D, Capobianco R. Sachs D, et al. Adv Orthop. 2013;2013:536128. doi: 10.1155/2013/536128. Epub 2013 Aug 13. Adv Orthop. 2013. PMID: 23997957 Free PMC article.

- Sacroiliac Joint Arthrodesis-MIS Technique with Titanium Implants: Report of the First 50 Patients and Outcomes. Rudolf L. Rudolf L. Open Orthop J. 2012;6:495-502. doi: 10.2174/1874325001206010495. Epub 2012 Nov 30. Open Orthop J. 2012. PMID: 23284593 Free PMC article.

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources.

- Ovid Technologies, Inc.

- Wolters Kluwer

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

- Case Report

- Open access

- Published: 15 August 2024

Arthroscopic reduction and hollow screw internal fixation for Eyres Type IIIA scapular coracoid fracture: a case report

- Weizhao Xie 1 na1 ,

- Dahai Hu 1 na1 ,

- Huige Hou ORCID: orcid.org/0009-0008-7766-6560 1 &

- Xiaofei Zheng 1

BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders volume 25 , Article number: 645 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

12 Accesses

Metrics details

A coracoid process fracture combined with an acromioclavicular (AC) joint dislocation is an uncommon injury that typically causes significant pain and limits shoulder movement. Open reduction and internal fixation have been the traditional treatment approach. However, arthroscopic techniques are emerging as a promising alternative for managing these injuries.

Case representation

A 35-year-old woman presented with right shoulder pain following an accidental fall. Imaging studies revealed a coracoid process fracture along with an AC joint dislocation. The fracture was classified as an Eyres Type IIIA, which warranted surgical intervention. Our team performed arthroscopic coracoid fracture reduction and internal fixation surgery, as well as AC joint dislocation repair using Kirschner wires. Six months after surgery, the patient demonstrated a satisfactory functional outcome with complete bone healing.

This case report highlights the potential of arthroscopic reduction and fixation as a novel treatment option for fractures of the coracoid base.

Peer Review reports

Scapular coracoid fractures are uncommon, accounting for only 0.5–1.0% of all fractures and representing just 3–13% of scapular fractures themselves [ 1 , 2 ]. These fractures can be classified into different types depending on their location. Traditionally, treatment involved open reduction and internal fixation of the displaced coracoid. The goal was to achieve either an anatomical reduction or a non-anatomical reduction. However, advancements in arthroscopic technology have made it possible to perform arthroscopic reduction and internal fixation for fractures at the base of the coracoid process [ 3 ]. This case report describes an Eyres Type IIIA fracture treated with osteosynthesis using an arthroscopic approach.

Fourteen days after an accidental fall, a 35-year-old woman presented with right shoulder pain. She described the pain as a dull ache located on the medial aspect of the joint. The pain worsened with any movement of the shoulder, and she also reported limitations in her right shoulder mobility.

Digital radiographs of the right shoulder joint, obtained at a local hospital, suggested a dislocation of the right acromioclavicular (AC) joint. However, no treatment was initiated at that facility.

Specialist physical examination

On physical examination, the right shoulder joint exhibited mild swelling without any visible deformity. However, there was significant tenderness on palpation near the medial aspect of the glenohumeral joint. Additionally, abnormal movement was detectable at this tender point. The active range of motion in the right shoulder joint was limited: flexion: 30°, extension: 15°, abduction: 40°, internal rotation: 5°, and external rotation: 5°. Due to the patient’s pain, the remainder of the physical examination was not completed.

Sensation in both upper limbs remained largely normal, and peripheral movement and circulation were unimpaired. Preoperative imaging is presented in Fig. 1 . Based on the clinical findings, a preoperative diagnosis of right coracoid process fracture and right AC joint dislocation was established.

A : The preoperative shoulder joint DR shown like this. Acromioclavicular joint dislocation and coracoid fracture area were indicated by the arrow. B : CT 3D reconstruction image of the coracoid fracture as seen in the main view. C : CT 3D reconstruction of the coracoid fracture seen from the top view

Intraoperative findings

Following general anesthesia with a brachial plexus block, the patient was positioned in a left lateral decubitus position with a 30° posterior tilt. The right upper limb was then externally rotated and secured in a position of forward flexion. Preoperative markings were made on the bony landmarks of the acromion, AC joint, and scapular spine.

A single incision, 2 cm below the posterolateral corner of the acromion and 1 cm medial, was created. Through this incision, a trocar was inserted towards the coracoid process to establish a standard posterior arthroscopic approach. An additional incision was made midway between the coracoid process and the acromion to create the anterior portal for shoulder arthroscopy.

Both standard anterior and posterior portals were used to visualize the glenohumeral joint. After entering the joint, the coracoacromial ligament was followed anteriorly to explore the coracoid process. A plasma knife was then used to meticulously dissect the surrounding synovium and attached tendons from the coracoid process.

Dissection continued until the superior surface of the coracoid base was fully exposed. Here, a fracture line with a displacement exceeding 3 mm was evident (Fig. 2 A). The area was further debrided to expose the inferior surface, ultimately achieving visualization of the superior, inferior, and lateral aspects of the coracoid base (Fig. 2 B).

A : The surrounding tissues were cleared to expose the fracture line at the base of the coracoid process under arthroscopy. B : Exposed the superior, inferior, and lateral aspects of the fracture line. The area indicated by the arrow is the fracture line

Surgical treatment plan

Through the posterior portal, a plasma knife and shaver were used to meticulously clear the synovium and fatty tissue around the coracoid process. Once a clear view of the superior aspect of the coracoid was obtained, the surgical approach was slightly widened.

Arthroscopy revealed an AC joint dislocation. Two Kirschner wires were strategically placed to temporally fix the dislocated joint. This facilitated the reduction of the fractured coracoid by minimizing resistance and creating favorable conditions for realignment.

Dissection continued until the base of the coracoid process was fully visualized under the arthroscope. The observed fracture displacement was consistent with the preoperative computed tomography (CT) reconstruction.

A suture was passed through the conjoint tendon superior to the coracoid process (Fig. 3 A and B). This suture served a dual purpose: securing the suture and utilizing the conjoint tendon to retract and mobilize the coracoid fragment.

A : During the operation, two K-wire needles were taken to fix the dislocated acromioclavicular joint, and the acromioclavicular joint was well reduced. B : The suture is inserted from the conjoint tendon to pull the fractured coracoid process under arthroscopy. C : The displaced coracoid process is pulled back to its original position by suture traction

Once anatomical reduction of the coracoid fracture was achieved (Fig. 3 C), two guide pins were strategically inserted through the coracoid process to stabilize the displaced bone (Fig. 4 A and B). Intraoperative confirmation ensured both anatomic reduction of the fracture fragments and stable guide pin fixation.

A : Intraoperative radiograph can be seen: after the reduction of the coracoid process is completed, two Guide Pins are placed to fix it. B : The direction of the two Guide Pins in vitro view is shown. C : The hollow screws were inserted along the Guide Pins, and the coracoid process is well reduced and fixed in place

Following guide pin placement, two hollow screws (diameter 3 mm, inner diameter 2.1 mm, length 36 mm and 32 m, Kaiwei Yierling) were inserted along the guide pin tracks. Post-screw insertion radiographs (Fig. 4 C) and arthroscopic visualization confirmed satisfactory fracture reduction (Fig. 4 C). The surgical procedure lasted approximately 150 min, with minimal blood loss (70 mL).

Postoperative Rehabilitation

For the first six weeks after surgery, the patient wore a sling to immobilize the affected shoulder. Restricted elbow flexion exercises were also initiated during this period. A physical therapist then guided the patient through a program of passive motion exercises for the shoulder joint with limited range.

At six weeks postoperatively, the range of motion in the shoulder joint was limited to 45° of abduction and 90° of forward flexion. Radiographs and CT scans confirmed bony union at the fracture site three months after surgery (Fig. 5 ).

A : CT of the shoulder joint showed that the coracoid fracture line was slightly blurred, and the fracture was initially healed (1 month postoperatively). B : CT of the shoulder joint showed that the fractured end of the coracoid process had healed significantly, and the fracture line had gradually disappeared (2 months postoperatively). C : Radiograph of the shoulder joint shows that the patient’s acromioclavicular joint is in place, and the coracoid fracture is healed(3 months postoperatively)

By the six-month follow-up, the patient’s range of motion had significantly improved, forward flexion: 150°, extension: 40°, abduction: 170°, internal rotation: 70°, and external rotation: 80°.

Discussion and conclusion

Current treatment guidelines for coracoid fractures recommend surgery for displaced fractures or those involving the shoulder’s superior suspensory complex [ 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 ]. Our patient’s Eyres Type IIIA coracoid fracture fulfilled these criteria. However, based on CT scans (Fig. 4 B and C) and arthroscopic visualization, the displacement was relatively minor. Therefore, we opted for arthroscopic reduction and internal fixation.

For fractures with severe displacement where arthroscopic reduction is not feasible, open surgery remains an option. Shariff et al [ 8 ]. suggest that most coracoid fractures can be managed conservatively without surgery, with intervention reserved for specific cases like athletes or patients with non-unions. Similarly, Caroline et al [ 9 ]. propose surgical indications including fracture displacement exceeding 1 cm on imaging, multiple disruptions, or persistent rotator cuff dysfunction. Both studies by Shariff et al. and Caroline et al. emphasize the importance of thorough preoperative assessment [ 8 , 9 ], highlighting the role of CT scans in guiding surgical planning.

Caroline et al [ 9 ]. suggest that AC joint dislocations with intact coracoclavicular ligaments may improve solely with coracoid process reduction, potentially avoiding AC joint fixation. However, our patient presented with a partial tear of this ligament, necessitating AC joint stabilization.

Current fixation techniques for AC joint dislocations include the Tight Rope technique and Kirschner wires [ 8 ]. While both hook plate and Tight Rope methods offer good fixation, they may have drawbacks such as longer surgery times and larger incisions, potentially increasing infection risk. Arthroscopic surgery itself carries a risk of intra-articular infection if complications arise.

Furthermore, the possibility of nonunion of coracoid process when coracoclavicular reconstruction (C-C reconstruction) is performed for coracoid process fractures can be one of the reasons for AC fixation with Kirschner wire [ 10 ]. Therefore, considering the advantages, we opted for Kirschner wire fixation for the AC joint.

This case highlights the potential of arthroscopy for treating a combined Eyres Type IIIA coracoid fracture and AC joint dislocation. The coracoid process plays a critical role in shoulder stability, forming part of the superior suspensory complex. It serves as an attachment site for several muscles (pectoralis minor, biceps brachii, and coracobrachialis muscles) and provides the origin for key ligaments (coracoclavicular, coracoacromial, coracohumeral, and superior transverse scapular). Additionally, vital neurovascular structures (brachial plexus nerves, axillary artery, and axillary vein) course near the deep surface of the pectoralis minor muscle [ 11 ].

These anatomical considerations make open surgical exposure of the coracoid base challenging, potentially risking damage to nearby structures. Arthroscopy offers a minimally invasive approach that overcomes these limitations. Utilizing both anterior and posterior portals, the surgeon can safely access the area around the glenohumeral joint with a plasma knife. This arthroscopic view allows for the meticulous removal of obstructing soft tissues, revealing the fracture line. The conjoint tendon above the coracoid can then be utilized for traction and reduction of the fractured segment.

Following reduction and internal fixation, an intraoperative radiograph confirmed the anatomical reduction of the coracoid process and proper placement of the implants. Over multiple follow-up visits within three months postoperatively, the patient’s progress aligned with the expected outcomes for arthroscopic treatment of coracoid base fractures.

The arthroscopic approach offers several advantages, including minimal tissue disruption, leading to faster recovery and reduced blood loss.

In conclusion, this case demonstrates the feasibility of arthroscopic treatment for fractures at the base of the coracoid process. Compared to traditional open reduction and internal fixation with a hook plate, as described by Zhang et al. [ 12 ], our arthroscopic approach with Kirschner wire fixation may minimize the size of the surgical wound and reduce the risk of infection. By three months postoperatively, the patient had regained near-normal shoulder function, and satisfactory outcomes were maintained at six-month follow-up. These findings suggest that arthroscopic treatment for coracoid process fractures with AC joint dislocation can achieve excellent clinical results. Further validation through multicenter, randomized controlled trials would strengthen this conclusion.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

Acromioclavicular

Coracoclavicular reconstruction

Computed tomography

van Doesburg PG, El Saddy S, Alta TD, van Noort A, van Bergen CJA. Treatment of coracoid process fractures: a systematic review. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2021;141(7):1091–100.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Rabbani GR, Cooper SM, Escobedo EM. An isolated coracoid fracture. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2012;41(4):120–1.

Brusalis CM, Mizels J, Moverman MA, Chalmers PN. Symptomatic coracoid fracture Nonunion treated with arthroscopic reduction and suture Anchor fixation: a Case Report. JBJS Case Connect 2024, 14(1).

Eyres KS, Brooks A, Stanley D. Fractures of the coracoid process. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1995;77(3):425–8.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Bartoníček J, Tuček M, Strnad T, Naňka O. Fractures of the coracoid process - pathoanatomy and classification: based on thirty nine cases with three dimensional computerised tomography reconstructions. Int Orthop. 2021;45(4):1009–15.

Thompson G, Van Den Heever A. Coracoid stress fracture in an elite fast bowler: description of a technique for CT-guided percutaneous screw fixation of coracoid fractures. Skeletal Radiol. 2019;48(10):1611–6.

Ruchelsman DE, Christoforou D, Rokito AS. Ipsilateral nonunions of the coracoid process and distal clavicle–a rare shoulder girdle fracture pattern. Bull NYU Hosp Jt Dis. 2010;68(1):33–7.

PubMed Google Scholar

Bishai SK, Ball GRS, Maceroni MR, Howard SD. Arthroscopic internal fixation of Coracoid fractures: Surgical technique guide. Arthrosc Tech. 2022;11(8):e1509–14.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Passaplan C, Beeler S, Bouaicha S, Wieser K. Arthroscopic management of a coracoid fracture Associated with Acromioclavicular dislocation: technical note. Arthrosc Tech. 2020;9(11):e1767–71.

Furuhata R, Tanji A. Symptomatic Nonunion of the coracoid process following Osteosynthesis using a suture button for coracoid process and distal clavicle fracture: a Case Report. Am J Case Rep. 2024;25:e943108.

Galvin JW, Kang J, Ma R, Li X. Fractures of the Coracoid process: evaluation, management, and outcomes. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2020;28(16):e706–15.

Zhang W, Huang B, Yang J, Xue P, Liu X. Fractured coracoid process with acromioclavicular joint dislocation: a case report. Medicine. 2020;99(39):e22324.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

This work was supported by Funded by Science and Technology Projects in Guangzhou (2023A03J1015, 2024A03J0971, 202201020087, 2024A04J4173),the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (21623119, 21623319), Science and Technology Innovation and Sports Culture Development Research Project of Guangdong Provincial Sports Bureau (GDSS2022M002), Project of China University Sports Association (202203007), Medical Scientific Research Foundation of Guangdong Province (A2023143), the Clinical Frontier Technology Program of the First Affiliated Hospital of Jinan University, China (No. JNU1AF-CFTP-2022-a01204), Project of Clinical Medical Research in the First Affiliated Hospital of Jinan University (2018009), Medical Joint Fund of Jinan University (YXJC2022005), the Research Fund Program of Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Speed Capability Research (2023B1212010009).

Author information

Weizhao Xie and Dahai Hu contributed equally to this work.

Authors and Affiliations

Department of Sports Medicine, The First Affiliated Hospital, Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Speed Capability, The Guangzhou Key Laboratory of Precision Orthopedics and Regenerative Medicine, Jinan University, Guangzhou, 510630, PR China

Weizhao Xie, Dahai Hu, Huige Hou & Xiaofei Zheng

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

WZX and DHH: data acquisition, literature search, manuscript preparation. WZX and DHH: data acquisition, literature search. HGH: medical management. WZX and DHH: pathological interpretation, manuscript preparation and editing. XFZ and HGH: revised and reviewed the manuscript for the final publication. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Correspondence to Dahai Hu , Huige Hou or Xiaofei Zheng .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The patient agreed to participate in this study. Informed consent was obtained from the patient prior to the study. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Jinan University.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Xie, W., Hu, D., Hou, H. et al. Arthroscopic reduction and hollow screw internal fixation for Eyres Type IIIA scapular coracoid fracture: a case report. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 25 , 645 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-024-07767-6

Download citation

Received : 18 March 2024

Accepted : 08 August 2024

Published : 15 August 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-024-07767-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Scapular coracoid fracture

- Internal fixation

- Arthroscopy

- Hollow screw

BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders

ISSN: 1471-2474

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Get new issue alerts Get alerts

- Submit a Manuscript

Secondary Logo

Journal logo.

Colleague's E-mail is Invalid

Your message has been successfully sent to your colleague.

Save my selection

Rehabilitation of a Painful Shoulder – A Perspective Biomechanical Approach

Raj, V. Vijay Samuel; Ukil, Kundan Das 1 ; Shetty, Aparna 2

Department of Sports Sciences, JSS College of Physiotherapy, Mysore, Karnataka, India

1 Department of Musculoskeletal and Sports Physiotherapy, Brainware School of Medical and Allied Health Sciences, Brainware University, Barasat, West Bengal, India

2 Department of Musculoskeletal and Sports Physiotherapy, JSS College of Physiotherapy, Mysore, Karnataka, India

Address for correspondence: Dr. V. Vijay Raj, Department of Sport Science, JSS College of Physiotherapy, Mg Road, Mysore - 570 004, Karnataka, India. E-mail: [email protected]

Received March 30, 2022

Received in revised form November 16, 2022

Accepted December 16, 2022

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

The deltoid muscle is often forgotten when it comes to the evaluation and planning of treatment in shoulder conditions. Shoulder dysfunction, rotator cuff tendinopathy, and frozen shoulder are the conditions that affect functioning in major cases. The study involved an exploration of possible causes of dysfunction, especially pain and overhead activities. The patient presented with chronic pain and decreased shoulder function. A suitable shoulder rehabilitation program was designed keeping the deltoid muscle denervation into consideration. The shoulder pain, range of motion, strength, and function were evaluated at the baseline and the end of 6 weeks. The results were correlated and explored to identify the involvement of the deltoid muscle. The study showed a positive test of deltoid muscle involvement, which was identified through the strength-duration curve. There was a clinically significant improvement observed in the patients' function. Hence, the study hypothesized that along with scapular stabilization, it is important to consider deltoid equally during the assessment and treatment plan in shoulder rehabilitation program.

INTRODUCTION

The shoulder complex is an intricately designed combination of the glenohumeral joint, sternoclavicular joint, acromioclavicular joint, and scapulothoracic joint formed by the clavicle, scapula, and humerus. Shoulder articular structures are intended primarily for mobility, allowing for a wide range of motion (ROM).[ 1 ] The freedom of movement at the shoulder complex requires both mobility and stability which rely on both static and dynamic stabilization.[ 2 ] Dynamic stabilization results from a unique functional balance between mobility and stability through forces by the muscles that rely on dynamic muscular control rather than passive forces. The shoulder complex, muscles provide a stable base for the upper limb movements, it is important that the stability of scapula is essential to carry out an efficient function. When there is a loss of stabilization factors due to various reasons, the shoulder complex is susceptible to instability and dysfunction.

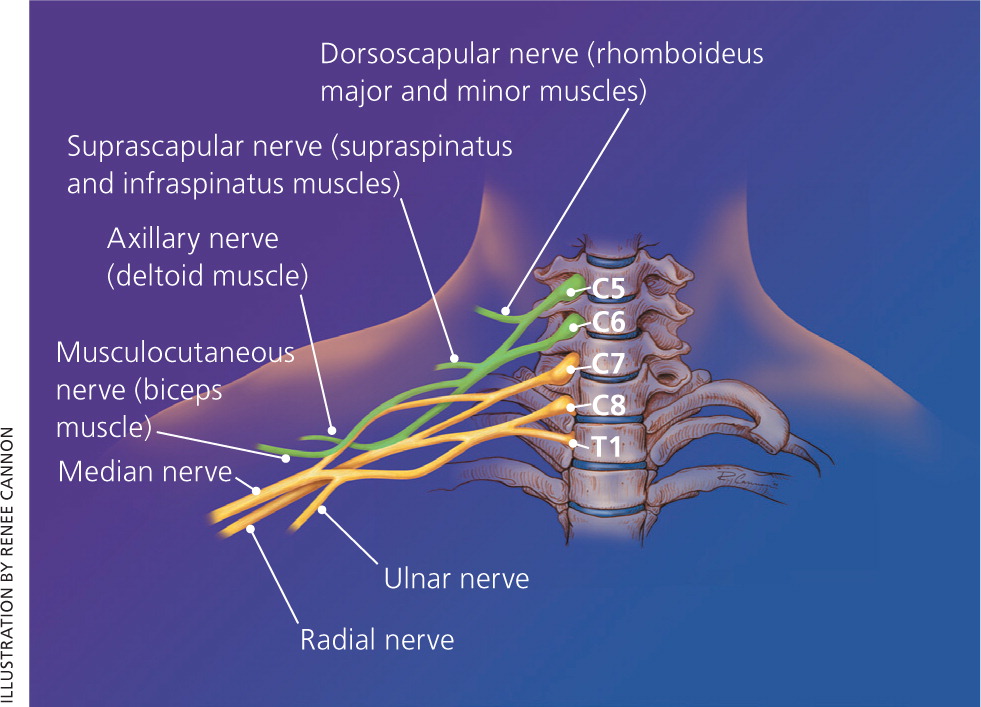

The common nerves that are involved in the shoulder are the axillary, long thoracic, and suprascapular and musculoskeletal nerves. The axillary nerve (AN) supplies the deltoid muscle, musculoskeletal nerve supplies the biceps, and may be entrapped or diseased. AN injury may present with axillary neuropathies caused due to various traumatic and compression injuries, also weakness of deltoid may be causative due to pathologies including subdeltoid bursa, acromion, and lateral clavicle.[ 3 ] Men are prone to AN injury than women at the ratio of 3:1.[ 4 ] Among the shoulder injuries, 9%–65% is AN injury.

The deltoid weakness can contribute to active loss of shoulder abduction, flexion, and extension and may be also caused due to AN injury, and caused due to anterior inferior dislocation, fracture, and fall on outstretched arm. The free portion of AN can be elongated due to displacement of the head of the humerus and may result in the avulsion of AN.[ 5 ] A special consideration needs to be made on the evaluation and functional diagnosis of shoulder dysfunction. The stability and mobility factors and ratio of contribution during upper limb function have to be considered in the assessment and plan of care during shoulder rehabilitation. This manuscript presents the interesting case study with an aim to present the importance of biomechanical evaluation and treatment, emphasizing on the evaluation of the auxiliary nerve involvement.

CASE REPORT

The client was a 63-year-old adult male, who visited the physiotherapy department at a tertiary hospital with complaints of pain at the left shoulder and arm for the past 6 months. He reported 1 st episode of injury during performing sumo squat, which included squats with wider base and holding a kettlebell and also later during bicep curl of 5 kg and triceps curls of 5 kg. The pain aggravated on any of the weightlifting activities since then. He consulted the orthopedic surgeon and diagnosed with partial width tear of the supraspinatus, subacromial impingement of rotator cuff, subdeltoid bursitis, and bicipital tenosynovitis. He was prescribed analgesics, advised to rest for 10 days, and referred to physiotherapy. He was treated with joint mobilization emphasizing on inferior glides with stretching of trapezius, and strengthening, and went for acupuncture. There was a 60%–70% reduction in the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) after treatment, but with a reoccurrence of pain intermittently. Three months later, during his trip abroad, with no specific reason mentioned, the pain increased in the night, for which he took therapy for 2 days from a joint specialist, where he found symptomatic relieve. The second episode occurred after lifting a suitcase of 23 kg to place it at the high head plank, which gave sudden sharp shooting pain to the patient at the left shoulder, which disabled him from lifting any weight. He had his visit to the department after this incident.

The sumo squat included standing with wide feet at shoulder width apart holding a kettlebell with both arms in front. Normally, the squat would include dropping the hips back and down, as sitting in a chair, allowing the kettlebell to swing down in between the legs, one would use the knee and hip to swing the kettlebell up and not the shoulders or one's arms. Probably, altered biomechanics would have been followed by the patient using more of his arms and shoulders, leading to a hypothesis of the shoulder muscles involvement leading to strain or AN injury.

The subjective and objective data were collected and presented with clinical reasoning form using a visual analysis. The data were plotted using Microsoft Office Excel software at baseline, before intervention and after 4 weeks of planned exercise program, and 6 weeks for discharge. Written consent was obtained from the client and the physiotherapy plan was clearly explained in his own language.

Patient evaluation and treatment planning

The client was interviewed with detailed subjective evaluation before starting of the exercise program. The client could not perform activities of daily living involving reach to the back by the left hand, and he complained about the difficulty in overhead activities and pain limiting the function. The initial evaluation of pain assessment, postural deformity, girth, muscle strength, and ROM evaluation was recorded and documented. The sensation over the neck and upper limb was intact. In the outcome measure, the Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (SPADI) of 71.53% was reported. In pain level, initial intensity of the pain was VAS 8 out of 10, the characteristics were chronic dull aching and most of the time patient experienced pain in the morning time, aggravating factor was due to stretch, weight lifting, sleeping on the affected side, and relieving factors were rest and heat application.

On observation, muscle atrophy in infraspinatus, supraspinatus, deltoid, triceps, and biceps was noticed. The posture assessment on the postural grid depicted a protracted shoulder, elevated shoulder on the left side, and winging of the scapula. The shoulder ROM during flexion, extension, abduction, and external and internal rotation was limited [ Table 1 ], with a firm end feel, pain onset (P1) followed by resistance limit (R2). The muscle strength and girth measurements were also taken shown in the table and abnormal glenohumeral rhythm (scapular dyskinesia) was noticed. Special tests for the shoulder were done to identify the underlying pathology. Empty can test, superior and inferior scratch test, Neer impingement test, speed's test, and Yergason's test, all were considered positive, these were in turn the interpretation of patient and the impingement of supraspinatus and biceps were possibly confirmed, with joint capsule involvement. Correlating the finding of special tests and kinetics, possibly a compression at the quadrilateral space may be considered for further evaluation.[ 6 , 7 ] The presenting symptoms of the patient were night pain and weakness in the shoulder–glenohumeral abduction and external rotator, without numbness to the lateral shoulder area. Thus, leading to a hypothesis of the involvement of the middle deltoid and the AN, this may be caused due to primary shoulder impingement syndrome, caused due to faulty shoulder position.

Baseline tests and follow-up were conducted before the start of the exercise program. The tests are joint ROM, muscle strength, VAS, and strength-duration curve (SDC). The follow-up tests were conducted every week and 4 weeks after to check the improvement, and with obtained results, the exercise program was changed for consecutive sessions based on the assessment using the same test methods and finally at 6 weeks for discharge. A minimal clinically important difference (MCID) for ROM of ≥9° was considered. The shoulder function was assessed using SPADI, considering a MCID of 8–13 points.[ 8 ] The muscle girth was assessed using a standard flexible inch tape and measured in centimeter (cm).[ 9 ]

Rehabilitation program

The exercise program was composed of 6 weeks [Annexure 1], planned in five phases, which included the baseline tests and every week follow-up tests. To reduce the pain at left shoulder ultrasound therapy (UST), faradic muscle stimulation for supraspinatus, biceps, and anterior and middle deltoid 30 contractions [Annexure 1].

Visual Analog Scale

The level of subjective pain was measured using VAS when the shoulder joint was moved, with 10 as the highest level of pain. Pain at the shoulder joint before the exercise was 8, and the pain level reduced to 6 in 4 days and to 4 in 2 weeks at the maximum joint range.

Muscle girth, strength, and function

The girth measurement showed an improvement with a difference of 4.5 cm in the left arm girth. Similarly, at left forearm showed a difference of 1 cm. The significant improvement in muscle strength was noted in shoulder flexors (anterior fibers of deltoid, long head of biceps, and supraspinatus) with a difference of 10 lbs and similarly in biceps muscle with a difference of 19 lbs. However, the strength of shoulder extensors, abductors, internal rotators, and external rotators showed improvement, it was negligible as the difference was <6 lbs. The results of the strength measured by handheld dynamometer are depicted in Table 1 . Improvement in function was achieved; SPADI outcome was noted at 71.53% in the baseline and 86.55% in the posttest, with a difference of improvement of 15%, with difference score of 40 points, which was far above the MCID.

The measurements were taken in the following order: shoulder flexion, abduction, internal rotation, and external rotation. Joint motion observed an increased range in all movements with an evident increase in shoulder internal and external rotation. The ROM improvement in flexion and abduction can be ignored considering the MCID and errors. The results of the ROM of shoulder joint are shown in Table 1 .

Strength duration curve

The SDC responses for the biceps muscle (AN) showed abnormal chronaxie (2.2 ms), with the curve representing a compression, showing a minimal kink [ Figure 1 ]. The posttest responses recorded a normal chronaxie (0.38 ms) representing a normal curve. An evident improvement in the strength response was observed depicting that the nerve function may be restored.

The study was conducted in five phases. In the first phase, the treatment plan was made after evaluating the patient. In the second phase, preliminary tests were conducted. In the third phase, the exercise protocol was programmed. In the fourth phase, reevaluation was done, and in the fifth phase redesigning of exercise program over 6 weeks, each of the sessions lasted for 1 h.

Historically, the assessment of musculoskeletal problems in the shoulder joint has been based on the premise that it is possible to isolate the individual structure at fault. In the differential diagnosis of shoulder dysfunction, it is essential to rule out the origin of pain, in this case, the evaluation findings hypothesized that it might be due to AN pathology involving the deltoid muscle. In this case, postexercise, there was a lag in the shoulder flexor strength, in contrary to the biceps brachii muscle showing an excellent improvement in strength, when compared with the unaffected side. This leads to the confirmation of the anterior deltoid muscle involvement. This study further concludes that in spite of strong improvement in the deltoid group of muscles, the strength was not achieved to match the unaffected side. Exercise programs of longer duration exceeding 6 weeks may be necessary to achieve actual strength with change in the resistance training programs.[ 10 ] Patient reported that the sumo squat with kettlebell exercises caused the first episode, this supports with the possibilities of abnormal kinematics and kinetics[ 11 ] of the shoulder and scapula, leading to AN injury. This study emphasizes, the biomechanical evaluation including movement analysis may aid in functional decision-making and planning an appropriate physiotherapy intervention. This may be evidently followed in sports injury management. Many times, the deltoid muscle is ignored during the shoulder evaluation. However, the shoulder stabilizers involving the scapula stability play an essential function during static and dynamic activities, it is necessary to consider the deltoid along with the scapular muscles during the assessment of shoulder dysfunction and plan an appropriate plan of care. In this study, the patients, glenohumeral accessory movements (glides) were optimal, but pain limiting the movement, and due to the reason passive mobilization techniques were not delivered. There was a significant improvement observed in the patients' function, both subjectively and objectively. The parameters such as SPADI, muscle strength, and muscle girth measurements have shown significant clinical improvement in recovery. The patient was enthusiastic and cooperative throughout the treatment session, and there were no difficulties observed by the patient to follow the exercise protocol.

The study showed a positive test of deltoid muscle involvement, which was identified through the strength-duration curve. There was a clinically significant improvement observed in the patients' function. Hence, the study hypothesized that along with scapular stabilization, it is important to consider deltoid equally during assessment and treatment plan in shoulder rehabilitation program.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Conflicts of interest.

There are no conflicts of interest.

Shoulder Rehabilitation Protocol:

- Passive and active stretching of pectorals and biceps muscle

- Faradic Stimulation – Deltoid inhibition techniques – Intermittent 100 Hz, 1 ms pulse duration, rest time 5–10 s. 20–30 contractions

- UST (1 Mhz, pulsed 1:1, 0.8 W/cm 2 , 4–6 min) calculated based on the standard operating procedure of the department of physiotherapy, and treatment calculation chart. (Watson, T. (2002). “Ultrasound Dose Calculations“ In Touch 101;14-17)

- Strengthening exercises comprised.

- Muscle setting exercises (isometrics)

- Resistance exercise with resistance band and dumbbells for shoulder flexors and abductors (10 rep × 3 sets) each in supine lying

- Horizontal abduction was planned to improve eccentric contraction of retractors and active stretching of pectorals (10reps × 3 sets)

- Retractor strengthening using resistance band (10 reps × 3 sets)