Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing a Literature Review

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

A literature review is a document or section of a document that collects key sources on a topic and discusses those sources in conversation with each other (also called synthesis ). The lit review is an important genre in many disciplines, not just literature (i.e., the study of works of literature such as novels and plays). When we say “literature review” or refer to “the literature,” we are talking about the research ( scholarship ) in a given field. You will often see the terms “the research,” “the scholarship,” and “the literature” used mostly interchangeably.

Where, when, and why would I write a lit review?

There are a number of different situations where you might write a literature review, each with slightly different expectations; different disciplines, too, have field-specific expectations for what a literature review is and does. For instance, in the humanities, authors might include more overt argumentation and interpretation of source material in their literature reviews, whereas in the sciences, authors are more likely to report study designs and results in their literature reviews; these differences reflect these disciplines’ purposes and conventions in scholarship. You should always look at examples from your own discipline and talk to professors or mentors in your field to be sure you understand your discipline’s conventions, for literature reviews as well as for any other genre.

A literature review can be a part of a research paper or scholarly article, usually falling after the introduction and before the research methods sections. In these cases, the lit review just needs to cover scholarship that is important to the issue you are writing about; sometimes it will also cover key sources that informed your research methodology.

Lit reviews can also be standalone pieces, either as assignments in a class or as publications. In a class, a lit review may be assigned to help students familiarize themselves with a topic and with scholarship in their field, get an idea of the other researchers working on the topic they’re interested in, find gaps in existing research in order to propose new projects, and/or develop a theoretical framework and methodology for later research. As a publication, a lit review usually is meant to help make other scholars’ lives easier by collecting and summarizing, synthesizing, and analyzing existing research on a topic. This can be especially helpful for students or scholars getting into a new research area, or for directing an entire community of scholars toward questions that have not yet been answered.

What are the parts of a lit review?

Most lit reviews use a basic introduction-body-conclusion structure; if your lit review is part of a larger paper, the introduction and conclusion pieces may be just a few sentences while you focus most of your attention on the body. If your lit review is a standalone piece, the introduction and conclusion take up more space and give you a place to discuss your goals, research methods, and conclusions separately from where you discuss the literature itself.

Introduction:

- An introductory paragraph that explains what your working topic and thesis is

- A forecast of key topics or texts that will appear in the review

- Potentially, a description of how you found sources and how you analyzed them for inclusion and discussion in the review (more often found in published, standalone literature reviews than in lit review sections in an article or research paper)

- Summarize and synthesize: Give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: Don’t just paraphrase other researchers – add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically Evaluate: Mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: Use transition words and topic sentence to draw connections, comparisons, and contrasts.

Conclusion:

- Summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance

- Connect it back to your primary research question

How should I organize my lit review?

Lit reviews can take many different organizational patterns depending on what you are trying to accomplish with the review. Here are some examples:

- Chronological : The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time, which helps familiarize the audience with the topic (for instance if you are introducing something that is not commonly known in your field). If you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order. Try to analyze the patterns, turning points, and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred (as mentioned previously, this may not be appropriate in your discipline — check with a teacher or mentor if you’re unsure).

- Thematic : If you have found some recurring central themes that you will continue working with throughout your piece, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic. For example, if you are reviewing literature about women and religion, key themes can include the role of women in churches and the religious attitude towards women.

- Qualitative versus quantitative research

- Empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the research by sociological, historical, or cultural sources

- Theoretical : In many humanities articles, the literature review is the foundation for the theoretical framework. You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts. You can argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach or combine various theorical concepts to create a framework for your research.

What are some strategies or tips I can use while writing my lit review?

Any lit review is only as good as the research it discusses; make sure your sources are well-chosen and your research is thorough. Don’t be afraid to do more research if you discover a new thread as you’re writing. More info on the research process is available in our "Conducting Research" resources .

As you’re doing your research, create an annotated bibliography ( see our page on the this type of document ). Much of the information used in an annotated bibliography can be used also in a literature review, so you’ll be not only partially drafting your lit review as you research, but also developing your sense of the larger conversation going on among scholars, professionals, and any other stakeholders in your topic.

Usually you will need to synthesize research rather than just summarizing it. This means drawing connections between sources to create a picture of the scholarly conversation on a topic over time. Many student writers struggle to synthesize because they feel they don’t have anything to add to the scholars they are citing; here are some strategies to help you:

- It often helps to remember that the point of these kinds of syntheses is to show your readers how you understand your research, to help them read the rest of your paper.

- Writing teachers often say synthesis is like hosting a dinner party: imagine all your sources are together in a room, discussing your topic. What are they saying to each other?

- Look at the in-text citations in each paragraph. Are you citing just one source for each paragraph? This usually indicates summary only. When you have multiple sources cited in a paragraph, you are more likely to be synthesizing them (not always, but often

- Read more about synthesis here.

The most interesting literature reviews are often written as arguments (again, as mentioned at the beginning of the page, this is discipline-specific and doesn’t work for all situations). Often, the literature review is where you can establish your research as filling a particular gap or as relevant in a particular way. You have some chance to do this in your introduction in an article, but the literature review section gives a more extended opportunity to establish the conversation in the way you would like your readers to see it. You can choose the intellectual lineage you would like to be part of and whose definitions matter most to your thinking (mostly humanities-specific, but this goes for sciences as well). In addressing these points, you argue for your place in the conversation, which tends to make the lit review more compelling than a simple reporting of other sources.

- UConn Library

- Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide

- Introduction

Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide — Introduction

- Getting Started

- How to Pick a Topic

- Strategies to Find Sources

- Evaluating Sources & Lit. Reviews

- Tips for Writing Literature Reviews

- Writing Literature Review: Useful Sites

- Citation Resources

- Other Academic Writings

What are Literature Reviews?

So, what is a literature review? "A literature review is an account of what has been published on a topic by accredited scholars and researchers. In writing the literature review, your purpose is to convey to your reader what knowledge and ideas have been established on a topic, and what their strengths and weaknesses are. As a piece of writing, the literature review must be defined by a guiding concept (e.g., your research objective, the problem or issue you are discussing, or your argumentative thesis). It is not just a descriptive list of the material available, or a set of summaries." Taylor, D. The literature review: A few tips on conducting it . University of Toronto Health Sciences Writing Centre.

Goals of Literature Reviews

What are the goals of creating a Literature Review? A literature could be written to accomplish different aims:

- To develop a theory or evaluate an existing theory

- To summarize the historical or existing state of a research topic

- Identify a problem in a field of research

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1997). Writing narrative literature reviews . Review of General Psychology , 1 (3), 311-320.

What kinds of sources require a Literature Review?

- A research paper assigned in a course

- A thesis or dissertation

- A grant proposal

- An article intended for publication in a journal

All these instances require you to collect what has been written about your research topic so that you can demonstrate how your own research sheds new light on the topic.

Types of Literature Reviews

What kinds of literature reviews are written?

Narrative review: The purpose of this type of review is to describe the current state of the research on a specific topic/research and to offer a critical analysis of the literature reviewed. Studies are grouped by research/theoretical categories, and themes and trends, strengths and weakness, and gaps are identified. The review ends with a conclusion section which summarizes the findings regarding the state of the research of the specific study, the gaps identify and if applicable, explains how the author's research will address gaps identify in the review and expand the knowledge on the topic reviewed.

- Example : Predictors and Outcomes of U.S. Quality Maternity Leave: A Review and Conceptual Framework: 10.1177/08948453211037398

Systematic review : "The authors of a systematic review use a specific procedure to search the research literature, select the studies to include in their review, and critically evaluate the studies they find." (p. 139). Nelson, L. K. (2013). Research in Communication Sciences and Disorders . Plural Publishing.

- Example : The effect of leave policies on increasing fertility: a systematic review: 10.1057/s41599-022-01270-w

Meta-analysis : "Meta-analysis is a method of reviewing research findings in a quantitative fashion by transforming the data from individual studies into what is called an effect size and then pooling and analyzing this information. The basic goal in meta-analysis is to explain why different outcomes have occurred in different studies." (p. 197). Roberts, M. C., & Ilardi, S. S. (2003). Handbook of Research Methods in Clinical Psychology . Blackwell Publishing.

- Example : Employment Instability and Fertility in Europe: A Meta-Analysis: 10.1215/00703370-9164737

Meta-synthesis : "Qualitative meta-synthesis is a type of qualitative study that uses as data the findings from other qualitative studies linked by the same or related topic." (p.312). Zimmer, L. (2006). Qualitative meta-synthesis: A question of dialoguing with texts . Journal of Advanced Nursing , 53 (3), 311-318.

- Example : Women’s perspectives on career successes and barriers: A qualitative meta-synthesis: 10.1177/05390184221113735

Literature Reviews in the Health Sciences

- UConn Health subject guide on systematic reviews Explanation of the different review types used in health sciences literature as well as tools to help you find the right review type

- << Previous: Getting Started

- Next: How to Pick a Topic >>

- Last Updated: Sep 21, 2022 2:16 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uconn.edu/literaturereview

Reference management. Clean and simple.

What is a literature review? [with examples]

What is a literature review?

The purpose of a literature review, how to write a literature review, the format of a literature review, general formatting rules, the length of a literature review, literature review examples, frequently asked questions about literature reviews, related articles.

A literature review is an assessment of the sources in a chosen topic of research.

In a literature review, you’re expected to report on the existing scholarly conversation, without adding new contributions.

If you are currently writing one, you've come to the right place. In the following paragraphs, we will explain:

- the objective of a literature review

- how to write a literature review

- the basic format of a literature review

Tip: It’s not always mandatory to add a literature review in a paper. Theses and dissertations often include them, whereas research papers may not. Make sure to consult with your instructor for exact requirements.

The four main objectives of a literature review are:

- Studying the references of your research area

- Summarizing the main arguments

- Identifying current gaps, stances, and issues

- Presenting all of the above in a text

Ultimately, the main goal of a literature review is to provide the researcher with sufficient knowledge about the topic in question so that they can eventually make an intervention.

The format of a literature review is fairly standard. It includes an:

- introduction that briefly introduces the main topic

- body that includes the main discussion of the key arguments

- conclusion that highlights the gaps and issues of the literature

➡️ Take a look at our guide on how to write a literature review to learn more about how to structure a literature review.

First of all, a literature review should have its own labeled section. You should indicate clearly in the table of contents where the literature can be found, and you should label this section as “Literature Review.”

➡️ For more information on writing a thesis, visit our guide on how to structure a thesis .

There is no set amount of words for a literature review, so the length depends on the research. If you are working with a large amount of sources, it will be long. If your paper does not depend entirely on references, it will be short.

Take a look at these three theses featuring great literature reviews:

- School-Based Speech-Language Pathologist's Perceptions of Sensory Food Aversions in Children [ PDF , see page 20]

- Who's Writing What We Read: Authorship in Criminological Research [ PDF , see page 4]

- A Phenomenological Study of the Lived Experience of Online Instructors of Theological Reflection at Christian Institutions Accredited by the Association of Theological Schools [ PDF , see page 56]

Literature reviews are most commonly found in theses and dissertations. However, you find them in research papers as well.

There is no set amount of words for a literature review, so the length depends on the research. If you are working with a large amount of sources, then it will be long. If your paper does not depend entirely on references, then it will be short.

No. A literature review should have its own independent section. You should indicate clearly in the table of contents where the literature review can be found, and label this section as “Literature Review.”

The main goal of a literature review is to provide the researcher with sufficient knowledge about the topic in question so that they can eventually make an intervention.

Literature Review - what is a Literature Review, why it is important and how it is done

What are literature reviews, goals of literature reviews, types of literature reviews, about this guide/licence.

- Strategies to Find Sources

- Evaluating Literature Reviews and Sources

- Tips for Writing Literature Reviews

- Writing Literature Review: Useful Sites

- Citation Resources

- Other Academic Writings

- Useful Resources

Help is Just a Click Away

Search our FAQ Knowledge base, ask a question, chat, send comments...

Go to LibAnswers

What is a literature review? "A literature review is an account of what has been published on a topic by accredited scholars and researchers. In writing the literature review, your purpose is to convey to your reader what knowledge and ideas have been established on a topic, and what their strengths and weaknesses are. As a piece of writing, the literature review must be defined by a guiding concept (e.g., your research objective, the problem or issue you are discussing, or your argumentative thesis). It is not just a descriptive list of the material available, or a set of summaries. " - Quote from Taylor, D. (n.d) "The literature review: A few tips on conducting it"

Source NC State University Libraries. This video is published under a Creative Commons 3.0 BY-NC-SA US license.

What are the goals of creating a Literature Review?

- To develop a theory or evaluate an existing theory

- To summarize the historical or existing state of a research topic

- Identify a problem in a field of research

- Baumeister, R.F. & Leary, M.R. (1997). "Writing narrative literature reviews," Review of General Psychology , 1(3), 311-320.

When do you need to write a Literature Review?

- When writing a prospectus or a thesis/dissertation

- When writing a research paper

- When writing a grant proposal

In all these cases you need to dedicate a chapter in these works to showcase what have been written about your research topic and to point out how your own research will shed a new light into these body of scholarship.

Literature reviews are also written as standalone articles as a way to survey a particular research topic in-depth. This type of literature reviews look at a topic from a historical perspective to see how the understanding of the topic have change through time.

What kinds of literature reviews are written?

- Narrative Review: The purpose of this type of review is to describe the current state of the research on a specific topic/research and to offer a critical analysis of the literature reviewed. Studies are grouped by research/theoretical categories, and themes and trends, strengths and weakness, and gaps are identified. The review ends with a conclusion section which summarizes the findings regarding the state of the research of the specific study, the gaps identify and if applicable, explains how the author's research will address gaps identify in the review and expand the knowledge on the topic reviewed.

- Book review essays/ Historiographical review essays : This is a type of review that focus on a small set of research books on a particular topic " to locate these books within current scholarship, critical methodologies, and approaches" in the field. - LARR

- Systematic review : "The authors of a systematic review use a specific procedure to search the research literature, select the studies to include in their review, and critically evaluate the studies they find." (p. 139). Nelson, L.K. (2013). Research in Communication Sciences and Disorders . San Diego, CA: Plural Publishing.

- Meta-analysis : "Meta-analysis is a method of reviewing research findings in a quantitative fashion by transforming the data from individual studies into what is called an effect size and then pooling and analyzing this information. The basic goal in meta-analysis is to explain why different outcomes have occurred in different studies." (p. 197). Roberts, M.C. & Ilardi, S.S. (2003). Handbook of Research Methods in Clinical Psychology . Malden, MA: Blackwell Pub.

- Meta-synthesis : "Qualitative meta-synthesis is a type of qualitative study that uses as data the findings from other qualitative studies linked by the same or related topic." (p.312). Zimmer, L. (2006). "Qualitative meta-synthesis: A question of dialoguing with texts," Journal of Advanced Nursing , 53(3), 311-318.

Guide adapted from "Literature Review" , a guide developed by Marisol Ramos used under CC BY 4.0 /modified from original.

- Next: Strategies to Find Sources >>

- Last Updated: Jul 3, 2024 10:56 AM

- URL: https://lit.libguides.com/Literature-Review

The Library, Technological University of the Shannon: Midwest

How to write a literature review introduction (+ examples)

The introduction to a literature review serves as your reader’s guide through your academic work and thought process. Explore the significance of literature review introductions in review papers, academic papers, essays, theses, and dissertations. We delve into the purpose and necessity of these introductions, explore the essential components of literature review introductions, and provide step-by-step guidance on how to craft your own, along with examples.

Why you need an introduction for a literature review

In academic writing , the introduction for a literature review is an indispensable component. Effective academic writing requires proper paragraph structuring to guide your reader through your argumentation. This includes providing an introduction to your literature review.

It is imperative to remember that you should never start sharing your findings abruptly. Even if there isn’t a dedicated introduction section .

When you need an introduction for a literature review

There are three main scenarios in which you need an introduction for a literature review:

What to include in a literature review introduction

It is crucial to customize the content and depth of your literature review introduction according to the specific format of your academic work.

Academic literature review paper

The introduction of an academic literature review paper, which does not rely on empirical data, often necessitates a more extensive introduction than the brief literature review introductions typically found in empirical papers. It should encompass:

Regular literature review section in an academic article or essay

In a standard 8000-word journal article, the literature review section typically spans between 750 and 1250 words. The first few sentences or the first paragraph within this section often serve as an introduction. It should encompass:

Introduction to a literature review chapter in thesis or dissertation

Some students choose to incorporate a brief introductory section at the beginning of each chapter, including the literature review chapter. Alternatively, others opt to seamlessly integrate the introduction into the initial sentences of the literature review itself. Both approaches are acceptable, provided that you incorporate the following elements:

Examples of literature review introductions

Example 1: an effective introduction for an academic literature review paper.

To begin, let’s delve into the introduction of an academic literature review paper. We will examine the paper “How does culture influence innovation? A systematic literature review”, which was published in 2018 in the journal Management Decision.

Example 2: An effective introduction to a literature review section in an academic paper

The second example represents a typical academic paper, encompassing not only a literature review section but also empirical data, a case study, and other elements. We will closely examine the introduction to the literature review section in the paper “The environmentalism of the subalterns: a case study of environmental activism in Eastern Kurdistan/Rojhelat”, which was published in 2021 in the journal Local Environment.

Thus, the author successfully introduces the literature review, from which point onward it dives into the main concept (‘subalternity’) of the research, and reviews the literature on socio-economic justice and environmental degradation.

Examples 3-5: Effective introductions to literature review chapters

Numerous universities offer online repositories where you can access theses and dissertations from previous years, serving as valuable sources of reference. Many of these repositories, however, may require you to log in through your university account. Nevertheless, a few open-access repositories are accessible to anyone, such as the one by the University of Manchester . It’s important to note though that copyright restrictions apply to these resources, just as they would with published papers.

Master’s thesis literature review introduction

Phd thesis literature review chapter introduction, phd thesis literature review introduction.

The last example is the doctoral thesis Metacognitive strategies and beliefs: Child correlates and early experiences Chan, K. Y. M. (Author). 31 Dec 2020 . The author clearly conducted a systematic literature review, commencing the review section with a discussion of the methodology and approach employed in locating and analyzing the selected records.

Steps to write your own literature review introduction

Master academia, get new content delivered directly to your inbox, the best answers to "what are your plans for the future", 10 tips for engaging your audience in academic writing, related articles, minor revisions: sample peer review comments and examples, sample emails to your thesis supervisor, co-authorship guidelines to successfully co-author a scientific paper, how to select a journal for publication as a phd student.

Harvey Cushing/John Hay Whitney Medical Library

- Collections

- Research Help

YSN Doctoral Programs: Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

- Biomedical Databases

- Global (Public Health) Databases

- Soc. Sci., History, and Law Databases

- Grey Literature

- Trials Registers

- Data and Statistics

- Public Policy

- Google Tips

- Recommended Books

- Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

What is a literature review?

A literature review is an integrated analysis -- not just a summary-- of scholarly writings and other relevant evidence related directly to your research question. That is, it represents a synthesis of the evidence that provides background information on your topic and shows a association between the evidence and your research question.

A literature review may be a stand alone work or the introduction to a larger research paper, depending on the assignment. Rely heavily on the guidelines your instructor has given you.

Why is it important?

A literature review is important because it:

- Explains the background of research on a topic.

- Demonstrates why a topic is significant to a subject area.

- Discovers relationships between research studies/ideas.

- Identifies major themes, concepts, and researchers on a topic.

- Identifies critical gaps and points of disagreement.

- Discusses further research questions that logically come out of the previous studies.

APA7 Style resources

APA Style Blog - for those harder to find answers

1. Choose a topic. Define your research question.

Your literature review should be guided by your central research question. The literature represents background and research developments related to a specific research question, interpreted and analyzed by you in a synthesized way.

- Make sure your research question is not too broad or too narrow. Is it manageable?

- Begin writing down terms that are related to your question. These will be useful for searches later.

- If you have the opportunity, discuss your topic with your professor and your class mates.

2. Decide on the scope of your review

How many studies do you need to look at? How comprehensive should it be? How many years should it cover?

- This may depend on your assignment. How many sources does the assignment require?

3. Select the databases you will use to conduct your searches.

Make a list of the databases you will search.

Where to find databases:

- use the tabs on this guide

- Find other databases in the Nursing Information Resources web page

- More on the Medical Library web page

- ... and more on the Yale University Library web page

4. Conduct your searches to find the evidence. Keep track of your searches.

- Use the key words in your question, as well as synonyms for those words, as terms in your search. Use the database tutorials for help.

- Save the searches in the databases. This saves time when you want to redo, or modify, the searches. It is also helpful to use as a guide is the searches are not finding any useful results.

- Review the abstracts of research studies carefully. This will save you time.

- Use the bibliographies and references of research studies you find to locate others.

- Check with your professor, or a subject expert in the field, if you are missing any key works in the field.

- Ask your librarian for help at any time.

- Use a citation manager, such as EndNote as the repository for your citations. See the EndNote tutorials for help.

Review the literature

Some questions to help you analyze the research:

- What was the research question of the study you are reviewing? What were the authors trying to discover?

- Was the research funded by a source that could influence the findings?

- What were the research methodologies? Analyze its literature review, the samples and variables used, the results, and the conclusions.

- Does the research seem to be complete? Could it have been conducted more soundly? What further questions does it raise?

- If there are conflicting studies, why do you think that is?

- How are the authors viewed in the field? Has this study been cited? If so, how has it been analyzed?

Tips:

- Review the abstracts carefully.

- Keep careful notes so that you may track your thought processes during the research process.

- Create a matrix of the studies for easy analysis, and synthesis, across all of the studies.

- << Previous: Recommended Books

- Last Updated: Jun 20, 2024 9:08 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.yale.edu/YSNDoctoral

- Library Homepage

Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide: Literature Reviews?

- Literature Reviews?

- Strategies to Finding Sources

- Keeping up with Research!

- Evaluating Sources & Literature Reviews

- Organizing for Writing

- Writing Literature Review

- Other Academic Writings

What is a Literature Review?

So, what is a literature review .

"A literature review is an account of what has been published on a topic by accredited scholars and researchers. In writing the literature review, your purpose is to convey to your reader what knowledge and ideas have been established on a topic, and what their strengths and weaknesses are. As a piece of writing, the literature review must be defined by a guiding concept (e.g., your research objective, the problem or issue you are discussing, or your argumentative thesis). It is not just a descriptive list of the material available or a set of summaries." - Quote from Taylor, D. (n.d)."The Literature Review: A Few Tips on Conducting it".

- Citation: "The Literature Review: A Few Tips on Conducting it"

What kinds of literature reviews are written?

Each field has a particular way to do reviews for academic research literature. In the social sciences and humanities the most common are:

- Narrative Reviews: The purpose of this type of review is to describe the current state of the research on a specific research topic and to offer a critical analysis of the literature reviewed. Studies are grouped by research/theoretical categories, and themes and trends, strengths and weaknesses, and gaps are identified. The review ends with a conclusion section that summarizes the findings regarding the state of the research of the specific study, the gaps identify and if applicable, explains how the author's research will address gaps identify in the review and expand the knowledge on the topic reviewed.

- Book review essays/ Historiographical review essays : A type of literature review typical in History and related fields, e.g., Latin American studies. For example, the Latin American Research Review explains that the purpose of this type of review is to “(1) to familiarize readers with the subject, approach, arguments, and conclusions found in a group of books whose common focus is a historical period; a country or region within Latin America; or a practice, development, or issue of interest to specialists and others; (2) to locate these books within current scholarship, critical methodologies, and approaches; and (3) to probe the relation of these new books to previous work on the subject, especially canonical texts. Unlike individual book reviews, the cluster reviews found in LARR seek to address the state of the field or discipline and not solely the works at issue.” - LARR

What are the Goals of Creating a Literature Review?

- To develop a theory or evaluate an existing theory

- To summarize the historical or existing state of a research topic

- Identify a problem in a field of research

- Baumeister, R.F. & Leary, M.R. (1997). "Writing narrative literature reviews," Review of General Psychology , 1(3), 311-320.

When do you need to write a Literature Review?

- When writing a prospectus or a thesis/dissertation

- When writing a research paper

- When writing a grant proposal

In all these cases you need to dedicate a chapter in these works to showcase what has been written about your research topic and to point out how your own research will shed new light into a body of scholarship.

Where I can find examples of Literature Reviews?

Note: In the humanities, even if they don't use the term "literature review", they may have a dedicated chapter that reviewed the "critical bibliography" or they incorporated that review in the introduction or first chapter of the dissertation, book, or article.

- UCSB electronic theses and dissertations In partnership with the Graduate Division, the UC Santa Barbara Library is making available theses and dissertations produced by UCSB students. Currently included in ADRL are theses and dissertations that were originally filed electronically, starting in 2011. In future phases of ADRL, all theses and dissertations created by UCSB students may be digitized and made available.

Where to Find Standalone Literature Reviews

Literature reviews are also written as standalone articles as a way to survey a particular research topic in-depth. This type of literature review looks at a topic from a historical perspective to see how the understanding of the topic has changed over time.

- Find e-Journals for Standalone Literature Reviews The best way to get familiar with and to learn how to write literature reviews is by reading them. You can use our Journal Search option to find journals that specialize in publishing literature reviews from major disciplines like anthropology, sociology, etc. Usually these titles are called, "Annual Review of [discipline name] OR [Discipline name] Review. This option works best if you know the title of the publication you are looking for. Below are some examples of these journals! more... less... Journal Search can be found by hovering over the link for Research on the library website.

Social Sciences

- Annual Review of Anthropology

- Annual Review of Political Science

- Annual Review of Sociology

- Ethnic Studies Review

Hard science and health sciences:

- Annual Review of Biomedical Data Science

- Annual Review of Materials Science

- Systematic Review From journal site: "The journal Systematic Reviews encompasses all aspects of the design, conduct, and reporting of systematic reviews" in the health sciences.

- << Previous: Overview

- Next: Strategies to Finding Sources >>

- Last Updated: Mar 5, 2024 11:44 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.ucsb.edu/litreview

- University of Texas Libraries

Literature Reviews

- What is a literature review?

- Steps in the Literature Review Process

- Define your research question

- Determine inclusion and exclusion criteria

- Choose databases and search

- Review Results

- Synthesize Results

- Analyze Results

- Librarian Support

- Artificial Intelligence (AI) Tools

What is a Literature Review?

A literature or narrative review is a comprehensive review and analysis of the published literature on a specific topic or research question. The literature that is reviewed contains: books, articles, academic articles, conference proceedings, association papers, and dissertations. It contains the most pertinent studies and points to important past and current research and practices. It provides background and context, and shows how your research will contribute to the field.

A literature review should:

- Provide a comprehensive and updated review of the literature;

- Explain why this review has taken place;

- Articulate a position or hypothesis;

- Acknowledge and account for conflicting and corroborating points of view

From S age Research Methods

Purpose of a Literature Review

A literature review can be written as an introduction to a study to:

- Demonstrate how a study fills a gap in research

- Compare a study with other research that's been done

Or it can be a separate work (a research article on its own) which:

- Organizes or describes a topic

- Describes variables within a particular issue/problem

Limitations of a Literature Review

Some of the limitations of a literature review are:

- It's a snapshot in time. Unlike other reviews, this one has beginning, a middle and an end. There may be future developments that could make your work less relevant.

- It may be too focused. Some niche studies may miss the bigger picture.

- It can be difficult to be comprehensive. There is no way to make sure all the literature on a topic was considered.

- It is easy to be biased if you stick to top tier journals. There may be other places where people are publishing exemplary research. Look to open access publications and conferences to reflect a more inclusive collection. Also, make sure to include opposing views (and not just supporting evidence).

Source: Grant, Maria J., and Andrew Booth. “A Typology of Reviews: An Analysis of 14 Review Types and Associated Methodologies.” Health Information & Libraries Journal, vol. 26, no. 2, June 2009, pp. 91–108. Wiley Online Library, doi:10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x.

Meryl Brodsky : Communication and Information Studies

Hannah Chapman Tripp : Biology, Neuroscience

Carolyn Cunningham : Human Development & Family Sciences, Psychology, Sociology

Larayne Dallas : Engineering

Janelle Hedstrom : Special Education, Curriculum & Instruction, Ed Leadership & Policy

Susan Macicak : Linguistics

Imelda Vetter : Dell Medical School

For help in other subject areas, please see the guide to library specialists by subject .

Periodically, UT Libraries runs a workshop covering the basics and library support for literature reviews. While we try to offer these once per academic year, we find providing the recording to be helpful to community members who have missed the session. Following is the most recent recording of the workshop, Conducting a Literature Review. To view the recording, a UT login is required.

- October 26, 2022 recording

- Last Updated: Jul 30, 2024 9:33 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.utexas.edu/literaturereviews

Frequently asked questions

What is the purpose of a literature review.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

Frequently asked questions: Academic writing

A rhetorical tautology is the repetition of an idea of concept using different words.

Rhetorical tautologies occur when additional words are used to convey a meaning that has already been expressed or implied. For example, the phrase “armed gunman” is a tautology because a “gunman” is by definition “armed.”

A logical tautology is a statement that is always true because it includes all logical possibilities.

Logical tautologies often take the form of “either/or” statements (e.g., “It will rain, or it will not rain”) or employ circular reasoning (e.g., “she is untrustworthy because she can’t be trusted”).

You may have seen both “appendices” or “appendixes” as pluralizations of “ appendix .” Either spelling can be used, but “appendices” is more common (including in APA Style ). Consistency is key here: make sure you use the same spelling throughout your paper.

The purpose of a lab report is to demonstrate your understanding of the scientific method with a hands-on lab experiment. Course instructors will often provide you with an experimental design and procedure. Your task is to write up how you actually performed the experiment and evaluate the outcome.

In contrast, a research paper requires you to independently develop an original argument. It involves more in-depth research and interpretation of sources and data.

A lab report is usually shorter than a research paper.

The sections of a lab report can vary between scientific fields and course requirements, but it usually contains the following:

- Title: expresses the topic of your study

- Abstract: summarizes your research aims, methods, results, and conclusions

- Introduction: establishes the context needed to understand the topic

- Method: describes the materials and procedures used in the experiment

- Results: reports all descriptive and inferential statistical analyses

- Discussion: interprets and evaluates results and identifies limitations

- Conclusion: sums up the main findings of your experiment

- References: list of all sources cited using a specific style (e.g. APA)

- Appendices: contains lengthy materials, procedures, tables or figures

A lab report conveys the aim, methods, results, and conclusions of a scientific experiment . Lab reports are commonly assigned in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields.

The abstract is the very last thing you write. You should only write it after your research is complete, so that you can accurately summarize the entirety of your thesis , dissertation or research paper .

If you’ve gone over the word limit set for your assignment, shorten your sentences and cut repetition and redundancy during the editing process. If you use a lot of long quotes , consider shortening them to just the essentials.

If you need to remove a lot of words, you may have to cut certain passages. Remember that everything in the text should be there to support your argument; look for any information that’s not essential to your point and remove it.

To make this process easier and faster, you can use a paraphrasing tool . With this tool, you can rewrite your text to make it simpler and shorter. If that’s not enough, you can copy-paste your paraphrased text into the summarizer . This tool will distill your text to its core message.

Revising, proofreading, and editing are different stages of the writing process .

- Revising is making structural and logical changes to your text—reformulating arguments and reordering information.

- Editing refers to making more local changes to things like sentence structure and phrasing to make sure your meaning is conveyed clearly and concisely.

- Proofreading involves looking at the text closely, line by line, to spot any typos and issues with consistency and correct them.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

Avoid citing sources in your abstract . There are two reasons for this:

- The abstract should focus on your original research, not on the work of others.

- The abstract should be self-contained and fully understandable without reference to other sources.

There are some circumstances where you might need to mention other sources in an abstract: for example, if your research responds directly to another study or focuses on the work of a single theorist. In general, though, don’t include citations unless absolutely necessary.

An abstract is a concise summary of an academic text (such as a journal article or dissertation ). It serves two main purposes:

- To help potential readers determine the relevance of your paper for their own research.

- To communicate your key findings to those who don’t have time to read the whole paper.

Abstracts are often indexed along with keywords on academic databases, so they make your work more easily findable. Since the abstract is the first thing any reader sees, it’s important that it clearly and accurately summarizes the contents of your paper.

In a scientific paper, the methodology always comes after the introduction and before the results , discussion and conclusion . The same basic structure also applies to a thesis, dissertation , or research proposal .

Depending on the length and type of document, you might also include a literature review or theoretical framework before the methodology.

Whether you’re publishing a blog, submitting a research paper , or even just writing an important email, there are a few techniques you can use to make sure it’s error-free:

- Take a break : Set your work aside for at least a few hours so that you can look at it with fresh eyes.

- Proofread a printout : Staring at a screen for too long can cause fatigue – sit down with a pen and paper to check the final version.

- Use digital shortcuts : Take note of any recurring mistakes (for example, misspelling a particular word, switching between US and UK English , or inconsistently capitalizing a term), and use Find and Replace to fix it throughout the document.

If you want to be confident that an important text is error-free, it might be worth choosing a professional proofreading service instead.

Editing and proofreading are different steps in the process of revising a text.

Editing comes first, and can involve major changes to content, structure and language. The first stages of editing are often done by authors themselves, while a professional editor makes the final improvements to grammar and style (for example, by improving sentence structure and word choice ).

Proofreading is the final stage of checking a text before it is published or shared. It focuses on correcting minor errors and inconsistencies (for example, in punctuation and capitalization ). Proofreaders often also check for formatting issues, especially in print publishing.

The cost of proofreading depends on the type and length of text, the turnaround time, and the level of services required. Most proofreading companies charge per word or page, while freelancers sometimes charge an hourly rate.

For proofreading alone, which involves only basic corrections of typos and formatting mistakes, you might pay as little as $0.01 per word, but in many cases, your text will also require some level of editing , which costs slightly more.

It’s often possible to purchase combined proofreading and editing services and calculate the price in advance based on your requirements.

There are many different routes to becoming a professional proofreader or editor. The necessary qualifications depend on the field – to be an academic or scientific proofreader, for example, you will need at least a university degree in a relevant subject.

For most proofreading jobs, experience and demonstrated skills are more important than specific qualifications. Often your skills will be tested as part of the application process.

To learn practical proofreading skills, you can choose to take a course with a professional organization such as the Society for Editors and Proofreaders . Alternatively, you can apply to companies that offer specialized on-the-job training programmes, such as the Scribbr Academy .

Ask our team

Want to contact us directly? No problem. We are always here for you.

- Email [email protected]

- Start live chat

- Call +1 (510) 822-8066

- WhatsApp +31 20 261 6040

Our team helps students graduate by offering:

- A world-class citation generator

- Plagiarism Checker software powered by Turnitin

- Innovative Citation Checker software

- Professional proofreading services

- Over 300 helpful articles about academic writing, citing sources, plagiarism, and more

Scribbr specializes in editing study-related documents . We proofread:

- PhD dissertations

- Research proposals

- Personal statements

- Admission essays

- Motivation letters

- Reflection papers

- Journal articles

- Capstone projects

Scribbr’s Plagiarism Checker is powered by elements of Turnitin’s Similarity Checker , namely the plagiarism detection software and the Internet Archive and Premium Scholarly Publications content databases .

The add-on AI detector is powered by Scribbr’s proprietary software.

The Scribbr Citation Generator is developed using the open-source Citation Style Language (CSL) project and Frank Bennett’s citeproc-js . It’s the same technology used by dozens of other popular citation tools, including Mendeley and Zotero.

You can find all the citation styles and locales used in the Scribbr Citation Generator in our publicly accessible repository on Github .

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Grad Med Educ

- v.8(3); 2016 Jul

The Literature Review: A Foundation for High-Quality Medical Education Research

a These are subscription resources. Researchers should check with their librarian to determine their access rights.

Despite a surge in published scholarship in medical education 1 and rapid growth in journals that publish educational research, manuscript acceptance rates continue to fall. 2 Failure to conduct a thorough, accurate, and up-to-date literature review identifying an important problem and placing the study in context is consistently identified as one of the top reasons for rejection. 3 , 4 The purpose of this editorial is to provide a road map and practical recommendations for planning a literature review. By understanding the goals of a literature review and following a few basic processes, authors can enhance both the quality of their educational research and the likelihood of publication in the Journal of Graduate Medical Education ( JGME ) and in other journals.

The Literature Review Defined

In medical education, no organization has articulated a formal definition of a literature review for a research paper; thus, a literature review can take a number of forms. Depending on the type of article, target journal, and specific topic, these forms will vary in methodology, rigor, and depth. Several organizations have published guidelines for conducting an intensive literature search intended for formal systematic reviews, both broadly (eg, PRISMA) 5 and within medical education, 6 and there are excellent commentaries to guide authors of systematic reviews. 7 , 8

- A literature review forms the basis for high-quality medical education research and helps maximize relevance, originality, generalizability, and impact.

- A literature review provides context, informs methodology, maximizes innovation, avoids duplicative research, and ensures that professional standards are met.

- Literature reviews take time, are iterative, and should continue throughout the research process.

- Researchers should maximize the use of human resources (librarians, colleagues), search tools (databases/search engines), and existing literature (related articles).

- Keeping organized is critical.

Such work is outside the scope of this article, which focuses on literature reviews to inform reports of original medical education research. We define such a literature review as a synthetic review and summary of what is known and unknown regarding the topic of a scholarly body of work, including the current work's place within the existing knowledge . While this type of literature review may not require the intensive search processes mandated by systematic reviews, it merits a thoughtful and rigorous approach.

Purpose and Importance of the Literature Review

An understanding of the current literature is critical for all phases of a research study. Lingard 9 recently invoked the “journal-as-conversation” metaphor as a way of understanding how one's research fits into the larger medical education conversation. As she described it: “Imagine yourself joining a conversation at a social event. After you hang about eavesdropping to get the drift of what's being said (the conversational equivalent of the literature review), you join the conversation with a contribution that signals your shared interest in the topic, your knowledge of what's already been said, and your intention.” 9

The literature review helps any researcher “join the conversation” by providing context, informing methodology, identifying innovation, minimizing duplicative research, and ensuring that professional standards are met. Understanding the current literature also promotes scholarship, as proposed by Boyer, 10 by contributing to 5 of the 6 standards by which scholarly work should be evaluated. 11 Specifically, the review helps the researcher (1) articulate clear goals, (2) show evidence of adequate preparation, (3) select appropriate methods, (4) communicate relevant results, and (5) engage in reflective critique.

Failure to conduct a high-quality literature review is associated with several problems identified in the medical education literature, including studies that are repetitive, not grounded in theory, methodologically weak, and fail to expand knowledge beyond a single setting. 12 Indeed, medical education scholars complain that many studies repeat work already published and contribute little new knowledge—a likely cause of which is failure to conduct a proper literature review. 3 , 4

Likewise, studies that lack theoretical grounding or a conceptual framework make study design and interpretation difficult. 13 When theory is used in medical education studies, it is often invoked at a superficial level. As Norman 14 noted, when theory is used appropriately, it helps articulate variables that might be linked together and why, and it allows the researcher to make hypotheses and define a study's context and scope. Ultimately, a proper literature review is a first critical step toward identifying relevant conceptual frameworks.

Another problem is that many medical education studies are methodologically weak. 12 Good research requires trained investigators who can articulate relevant research questions, operationally define variables of interest, and choose the best method for specific research questions. Conducting a proper literature review helps both novice and experienced researchers select rigorous research methodologies.

Finally, many studies in medical education are “one-offs,” that is, single studies undertaken because the opportunity presented itself locally. Such studies frequently are not oriented toward progressive knowledge building and generalization to other settings. A firm grasp of the literature can encourage a programmatic approach to research.

Approaching the Literature Review

Considering these issues, journals have a responsibility to demand from authors a thoughtful synthesis of their study's position within the field, and it is the authors' responsibility to provide such a synthesis, based on a literature review. The aforementioned purposes of the literature review mandate that the review occurs throughout all phases of a study, from conception and design, to implementation and analysis, to manuscript preparation and submission.

Planning the literature review requires understanding of journal requirements, which vary greatly by journal ( table 1 ). Authors are advised to take note of common problems with reporting results of the literature review. Table 2 lists the most common problems that we have encountered as authors, reviewers, and editors.

Sample of Journals' Author Instructions for Literature Reviews Conducted as Part of Original Research Article a

Common Problem Areas for Reporting Literature Reviews in the Context of Scholarly Articles

Locating and Organizing the Literature

Three resources may facilitate identifying relevant literature: human resources, search tools, and related literature. As the process requires time, it is important to begin searching for literature early in the process (ie, the study design phase). Identifying and understanding relevant studies will increase the likelihood of designing a relevant, adaptable, generalizable, and novel study that is based on educational or learning theory and can maximize impact.

Human Resources

A medical librarian can help translate research interests into an effective search strategy, familiarize researchers with available information resources, provide information on organizing information, and introduce strategies for keeping current with emerging research. Often, librarians are also aware of research across their institutions and may be able to connect researchers with similar interests. Reaching out to colleagues for suggestions may help researchers quickly locate resources that would not otherwise be on their radar.

During this process, researchers will likely identify other researchers writing on aspects of their topic. Researchers should consider searching for the publications of these relevant researchers (see table 3 for search strategies). Additionally, institutional websites may include curriculum vitae of such relevant faculty with access to their entire publication record, including difficult to locate publications, such as book chapters, dissertations, and technical reports.

Strategies for Finding Related Researcher Publications in Databases and Search Engines

Search Tools and Related Literature

Researchers will locate the majority of needed information using databases and search engines. Excellent resources are available to guide researchers in the mechanics of literature searches. 15 , 16

Because medical education research draws on a variety of disciplines, researchers should include search tools with coverage beyond medicine (eg, psychology, nursing, education, and anthropology) and that cover several publication types, such as reports, standards, conference abstracts, and book chapters (see the box for several information resources). Many search tools include options for viewing citations of selected articles. Examining cited references provides additional articles for review and a sense of the influence of the selected article on its field.

Box Information Resources

- Web of Science a

- Education Resource Information Center (ERIC)

- Cumulative Index of Nursing & Allied Health (CINAHL) a

- Google Scholar

Once relevant articles are located, it is useful to mine those articles for additional citations. One strategy is to examine references of key articles, especially review articles, for relevant citations.

Getting Organized

As the aforementioned resources will likely provide a tremendous amount of information, organization is crucial. Researchers should determine which details are most important to their study (eg, participants, setting, methods, and outcomes) and generate a strategy for keeping those details organized and accessible. Increasingly, researchers utilize digital tools, such as Evernote, to capture such information, which enables accessibility across digital workspaces and search capabilities. Use of citation managers can also be helpful as they store citations and, in some cases, can generate bibliographies ( table 4 ).

Citation Managers

Knowing When to Say When

Researchers often ask how to know when they have located enough citations. Unfortunately, there is no magic or ideal number of citations to collect. One strategy for checking coverage of the literature is to inspect references of relevant articles. As researchers review references they will start noticing a repetition of the same articles with few new articles appearing. This can indicate that the researcher has covered the literature base on a particular topic.

Putting It All Together

In preparing to write a research paper, it is important to consider which citations to include and how they will inform the introduction and discussion sections. The “Instructions to Authors” for the targeted journal will often provide guidance on structuring the literature review (or introduction) and the number of total citations permitted for each article category. Reviewing articles of similar type published in the targeted journal can also provide guidance regarding structure and average lengths of the introduction and discussion sections.

When selecting references for the introduction consider those that illustrate core background theoretical and methodological concepts, as well as recent relevant studies. The introduction should be brief and present references not as a laundry list or narrative of available literature, but rather as a synthesized summary to provide context for the current study and to identify the gap in the literature that the study intends to fill. For the discussion, citations should be thoughtfully selected to compare and contrast the present study's findings with the current literature and to indicate how the present study moves the field forward.

To facilitate writing a literature review, journals are increasingly providing helpful features to guide authors. For example, the resources available through JGME include several articles on writing. 17 The journal Perspectives on Medical Education recently launched “The Writer's Craft,” which is intended to help medical educators improve their writing. Additionally, many institutions have writing centers that provide web-based materials on writing a literature review, and some even have writing coaches.

The literature review is a vital part of medical education research and should occur throughout the research process to help researchers design a strong study and effectively communicate study results and importance. To achieve these goals, researchers are advised to plan and execute the literature review carefully. The guidance in this editorial provides considerations and recommendations that may improve the quality of literature reviews.

Literature Reviews (in the Health Sciences)

- Goals of a Literature Review

- Select Citation Management Software

- Select databases to search

- Conduct searches

- Track your searches

- Select articles to include

- Extract information from articles

- Structure your review

- Find "fill-in" information

- Other sources and help

Keeping these goals in mind throughout your project will help you stay organized and focused.

A literature review helps the author:

- Understand the scope, history, and present state of knowledge in a specific topic

- Understand application of research concepts such as statistical tests and methodological choices

- Create a research project that complements the existing research or fills in gaps

A literature review helps the reader:

- Understand how your research project fits into the existing knowledge and research in a field

- Understand that a topic is important/relevant to the world and persuade them to keep reading your project

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Select Citation Management Software >>

- Last Updated: Jul 29, 2024 2:12 PM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/healthsciences/LitReview

- Open access

- Published: 26 August 2021

Advancing sustainable development goals through immunization: a literature review

- Catherine Decouttere 1 ,

- Kim De Boeck 1 &

- Nico Vandaele ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7687-7376 1

Globalization and Health volume 17 , Article number: 95 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

18k Accesses

40 Citations

33 Altmetric

Metrics details

Immunization directly impacts health (SDG3) and brings a contribution to 14 out of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), such as ending poverty, reducing hunger, and reducing inequalities. Therefore, immunization is recognized to play a central role in reaching the SDGs, especially in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Despite continuous interventions to strengthen immunization systems and to adequately respond to emergency immunization during epidemics, the immunization-related indicators for SDG3 lag behind in sub-Saharan Africa. Especially taking into account the current Covid19 pandemic, the current performance on the connected SDGs is both a cause and a result of this.

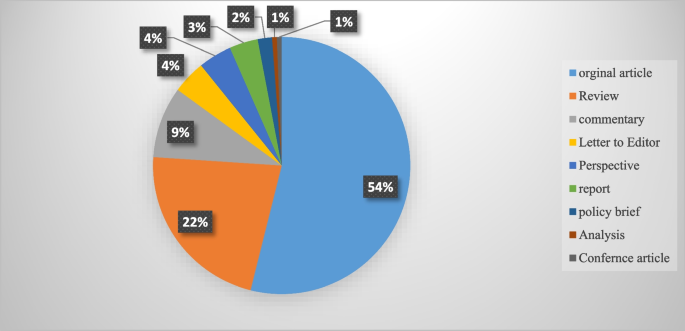

We conduct a literature review through a keyword search strategy complemented with handpicking and snowballing from earlier reviews. After title and abstract screening, we conducted a qualitative analysis of key insights and categorized them according to showing the impact of immunization on SDGs, sustainability challenges, and model-based solutions to these challenges.

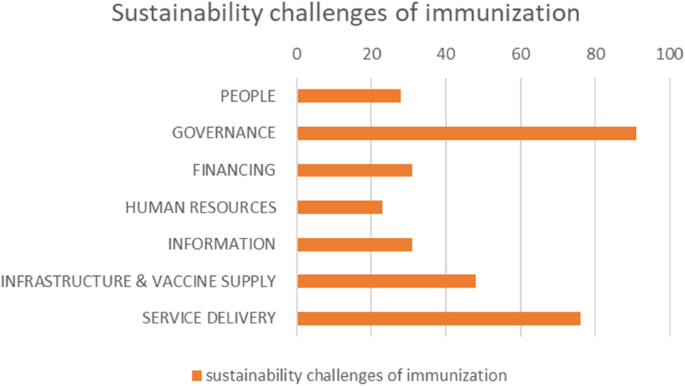

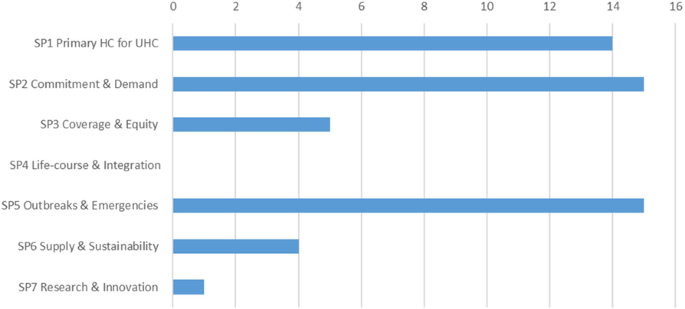

We reveal the leveraging mechanisms triggered by immunization and position them vis-à-vis the SDGs, within the framework of Public Health and Planetary Health. Several challenges for sustainable control of vaccine-preventable diseases are identified: access to immunization services, global vaccine availability to LMICs, context-dependent vaccine effectiveness, safe and affordable vaccines, local/regional vaccine production, public-private partnerships, and immunization capacity/capability building. Model-based approaches that support SDG-promoting interventions concerning immunization systems are analyzed in light of the strategic priorities of the Immunization Agenda 2030.

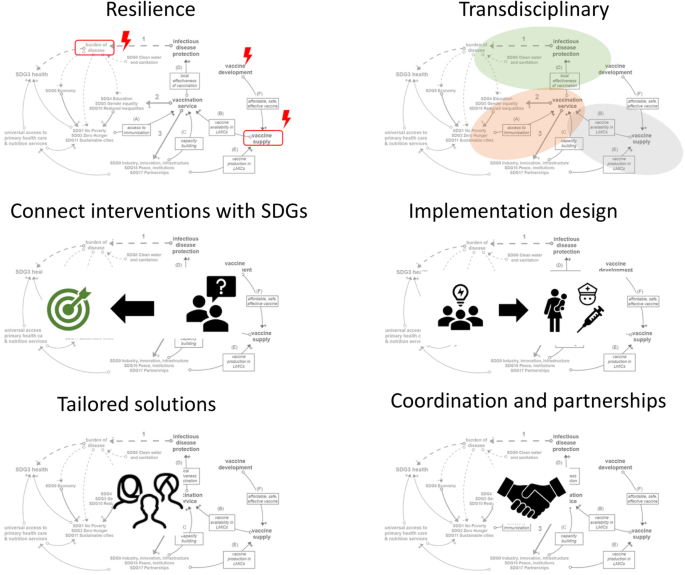

Conclusions

In general terms, it can be concluded that relevant future research requires (i) design for system resilience, (ii) transdisciplinary modeling, (iii) connecting interventions in immunization with SDG outcomes, (iv) designing interventions and their implementation simultaneously, (v) offering tailored solutions, and (vi) model coordination and integration of services and partnerships. The research and health community is called upon to join forces to activate existing knowledge, generate new insights and develop decision-supporting tools for Low-and Middle-Income Countries’ health authorities and communities to leverage immunization in its transformational role toward successfully meeting the SDGs in 2030.

With just one decade ahead to realize 17 ambitious but essential SDGs, most Sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries are struggling to meet and to sustain SDG3 Footnote 1 targets related to immunization: under-five mortality, elimination of vaccine-preventable diseases, and prevention of epidemics. There is a growing concern to support the transformation of immunization systems towards increased sustainability and resilience [ 1 , 2 ]. The 2020 Covid-19 pandemic supports this concern clearly, as it draws global attention and funds to restoring health systems across the globe and to the development of a vaccine, in an attempt to mitigate the devastating health and economic impact of the full-blown pandemic. Health care staff in Lower and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs) need to prepare their mostly weak health systems, already overburdened by ongoing struggles with active outbreaks of infectious diseases such as Measles, Ebola, and Lassa Fever, only to name a few.

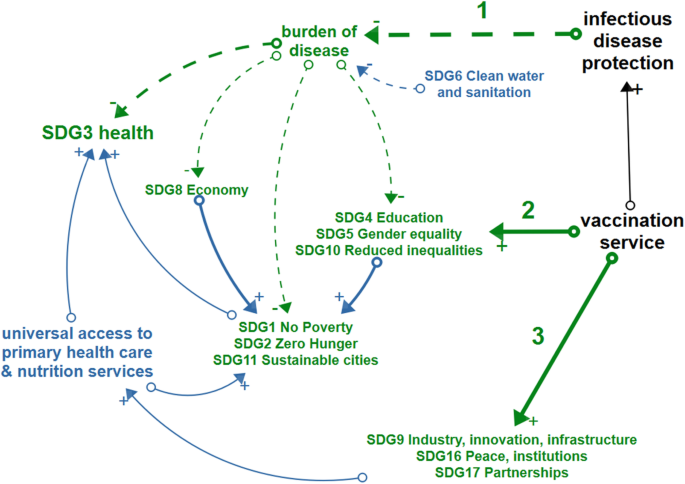

Immunization directly impacts health (SDG3) and brings a contribution to 14 out of the 17 SDGs [ 3 ]. Moreover, it has proven to be one of the most cost-effective and long-lasting health interventions [ 4 ], protecting individuals and communities both in stable times and during humanitarian crises.

Advancing both the health-related and other SDGs in LMICs through immunization requires appropriate methods and tools that can support strategic decision-making and program implementation. Furthermore, a multi-sectoral perspective within a system-based approach, that involves the relevant SDG dimensions, seems mandatory to preserve sustainability. This entails the observation that immunization is at the interface between natural and human-made systems. Although the existence of many bi-directional links between the two systems, this paper will focus on the sustainable impact of immunization on the SDGs. A core element within this system-based approach is the notion of adaptability as a means to endorse resilience.

The natural system houses pathogens (e.g., bacteria, viruses, parasites) in reservoirs such as soil, water, plants, animals, and humans. When humans are exposed to pathogens, the immune system is activated. If the activation is not effective, an infection takes place including further transmission. An infection survivor gains immunity and if enough in number, a community can develop herd immunity. Susceptibility of the population is related to the strength of the immune response against the pathogen, which is linked to age, nutrition, previous infection, and general health status. This points to the impact of immunization on other SDGs than SDG3 and vice versa.

Driven by environmental change due to natural or anthropogenic causes, such as floods, river dam constructions, conversion of forest into farmland, or climate change, pathogen ecologies adapt accordingly. This adaptation is key and gives rise to the presence of pathogens in environments where they could not flourish before. The same happens when an infected human travels or migrates to uninfected areas. A pathogen entering a new area is not recognized by the population’s naïve immune systems. Therefore it can emerge in communities and result in outbreaks, larger epidemics, or even pandemics like Covid-19.

Zoonoses are diseases that are transmissible from vertebrate animals, such as pets, livestock, or wildlife, to humans. Driven by ecological disruption and increased contact between humans and wild reservoir species, these pathogens found the opportunity to “jump the species barrier”, leading to a new human infectious disease. In specific, anthropogenic environmental disturbance, including the increased livestock population in close contact with wildlife animal populations, increased the risk of zoonotic infection from wildlife [ 5 ]. Furthermore, emerging infectious diseases are fueled by increasing population density in urban areas and the interaction between humans and wildlife, through encroachment, road building, deforestation, hunting, and global wildlife trade [ 5 ]. In addition, loss of biodiversity following anthropogenic disturbance was shown to increase the abundance of rodent-borne pathogens in central Kenya [ 6 ]. Most pandemic threats have been caused by viruses from zoonotic or vector-borne sources [ 7 ]: Ebola, SARS, MERS, H1N1 pandemic flu, and eventually also Covid-19.

These phenomena represent adaptive behavior and are clearly bidirectional in their interaction with the human-made immunization system. Concluded, there is an intimate connection between environmental, animal, and human health. The typical behavior attributed to social-ecological systems, as described by Whitmee et al. [ 8 ] applies: these systems coevolve across spatial and temporal scales, which explains endemic and emerging disease behavior, nonlinearity in disease transmission outside and during outbreaks, and scale-free phenomena such as a single adapted virus in a single infected traveler that is capable of infecting entire continents.

By providing an analysis of the existing body of research dedicated to sustainable immunization and by showing directions for future research in this field, we contribute to support the strategic priorities of the Immunization Agenda 2030 and contribute to the other SDGs.

In this paper, we discuss insights based on a literature review in which we explored (a) how immunization impacts the SDGs, (b) the factors that endanger the sustainability of immunization in LMICs (c) the research gap to enhance decision making for SDG-promoting implementations related to immunization.

Search strategy and information sources

Considering the broad array of disciplines involved, including epidemiology, system research, operations management, and anthropology, both Scopus and Pubmed databases were initially searched between January 1st 1990 and March 21, 2021. As the search term based on the SDGs needed to be expanded in order to identify papers before 2015 and papers that clearly expressed the idea behind sustainable development without mentioning the SDGs, it was replaced by variations of sustainability and resilience, which finally resulted in 3401 papers as shown in Table 1 .

Similar searches were performed in Pubmed. While screening the papers based on titles and abstracts, additional papers were handpicked and found through snowballing from review papers.

Data extraction and synthesis

Title screening removed papers without a direct connection to the SDGs, such as theoretical topics in immunology and vaccinology, vaccine efficacy and clinical trials, technical papers on human or veterinary vaccine development, and papers related to cybersecurity.

Abstract screening mainly removed papers on livestock immunization or detailed human immunology. Similarly, papers that only briefly listed the sustainability aspect in the limitations section of their research were excluded at this point. in terms of eligibility, papers dealing with models and methods that qualify as applicable and relevant for decision-makers, implementers, and other stakeholders were included. the insights from all the resulting papers were extracted in excel for qualitative synthesis. The inclusion criteria were based on Kovacs and Moshtari [ 9 ] and Besiou, Stapleton, and Van Wassenhove [ 10 ], as shown in Table 2 .

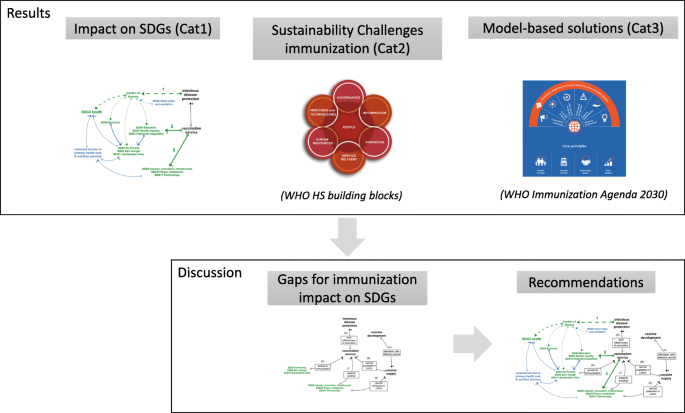

The analysis turned out the paper structure as shown in Fig. 1 . All eligible and included papers, for which the numbers are listed in Table 3 , were manually allocated to three categories. This has been initiated by one researcher and reviewed independently by two other researchers. A final meeting was arranged to reach a consensus.

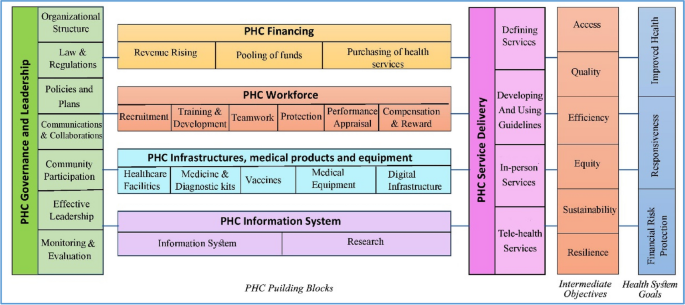

Paper structure. Paper structure combining literature analysis results with both the WHO Health System building blocks [ 11 ] and the WHO Immunization Agenda 2030 [ 2 ]