Service update: Some parts of the Library’s website will be down for maintenance on August 11.

Secondary menu

- Log in to your Library account

- Hours and Maps

- Connect from Off Campus

- UC Berkeley Home

Search form

Philosophy research and writing: sample papers.

- Reference Texts

- Sample Papers

- Writing Guides

Examples of Philosophical Writing

One of the most difficult things about writing philosophy papers as a new undergraduate is figuring out what a philosophy paper is supposed to look like! For many students here at Cal, a lower division philosophy class is the first experience they have with philosophical writing so when asked to write a paper it can be difficult to figure out exactly what a good paper would be. Below are a few examples of the kinds of papers you might be asked to write in a philosophy class here at Cal as well as the papers written by professional philosophers to which the sample papers are a response.

Precis Sample Paper

- "War and Peace in Islam" by Bassam Tibi In this paper, Bassam Tibi explores the Islamic position on war and peace as understood through the Quran and its interpretations in Islamic history.

- Max Deleon's Precis of Tibi on war and peace in Islam In this sample paper, Max Deleon, a former tutor at the university of Vermont gives a summary of an argument made by Bassam Tibi in his paper "War and Peace in Islam"

Critical Response to a Philosopher's Position

- "In Defense of Mereological Universalism" by Michael C. Rea In this paper, Michael Rea defends the position in ontology known as mereological universalism which he defines as that position which holds that "for any set S of disjoint objects, there is an object that the members of S compose."

- Max Deleon's critical response to Michael Rea on Mereological Universalism In lower division philosophy courses here at Cal, the most common type of paper that you will write will be one in which you are asked to respond to some given philosopher's position by uncovering some difficulty in that position. In this paper, Max Deleon critically examines Michael Rae's paper "In Defense of Mereological Universalism"

Exposition and Amending of Existing Philosopher's Position

- "Against Moral Rationalism, Philippa Foot" in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy The section "Against moral Rationalism" in the article "Philippa Foot" from the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy explores Foot's positions on moral motivation which Max Deleon deals with in the paper below.

- Max Deleon's exposition and emendation of "Morality as a System of Hypothetical Imperatives" In this paper Max Deleon looks at Philippa Foot's argument from "Morality as a System of Hypothetical Imperatives," raises a few possible objections, and proposes emendations to Foot's position to respond to those objections.

- "Morality as a System of Hypothetical Imperatives" by Philippa Foot One of the most influential paper in 20th century philosophy, Philippa Foot's "Morality as a System of Hypothetical Impreatives" tackles to dominant Kantian conception of the nature of morality and offers an alternative understanding of the nature of morality.

- << Previous: Reference Texts

- Next: Writing Guides >>

- Last Updated: May 19, 2020 2:25 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.berkeley.edu/philosophy_writing

Simon Fraser University Engaging the World

Department of philosophy.

- A-Z directory

Writing A Philosophy Paper

Copyright © 1993 by Peter Horban Simon Fraser University

THINGS TO AVOID IN YOUR PHILOSOPHY ESSAY

- Lengthy introductions. These are entirely unnecessary and of no interest to the informed reader. There is no need to point out that your topic is an important one, and one that has interested philosophers for hundreds of years. Introductions should be as brief as possible. In fact, I recommend that you think of your paper as not having an introduction at all. Go directly to your topic.

- Lengthy quotations. Inexperienced writers rely too heavily on quotations and paraphrases. Direct quotation is best restricted to those cases where it is essential to establish another writer's exact selection of words. Even paraphrasing should be kept to a minimum. After all, it is your paper. It is your thoughts that your instructor is concerned with. Keep that in mind, especially when your essay topic requires you to critically assess someone else's views.

- Fence sitting. Do not present a number of positions in your paper and then end by saying that you are not qualified to settle the matter. In particular, do not close by saying that philosophers have been divided over this issue for as long as humans have been keeping record and you cannot be expected to resolve the dispute in a few short pages. Your instructor knows that. But you can be expected to take a clear stand based on an evaluation of the argument(s) presented. Go out on a limb. If you have argued well, it will support you.

- Cuteness. Good philosophical writing usually has an air of simple dignity about it. Your topic is no joke. No writers whose views you have been asked to read are idiots. (If you think they are, then you have not understood them.) Name calling is inappropriate and could never substitute for careful argumentation anyway.

- Begging the question. You are guilty of begging the question (or circular reasoning) on a particular issue if you somehow presuppose the truth of whatever it is that you are trying to show in the course of arguing for it. Here is a quick example. If Smith argues that abortion is morally wrong on the grounds that it amounts to murder, Smith begs the question. Smith presupposes a particular stand on the moral status of abortion - the stand represented by the conclusion of the argument. To see that this is so, notice that the person who denies the conclusion - that abortion is morally wrong - will not accept Smith's premise that it amounts to murder, since murder is, by definition, morally wrong.

- When arguing against other positions, it is important to realize that you cannot show that your opponents are mistaken just by claiming that their overall conclusions are false. Nor will it do simply to claim that at least one of their premises is false. You must demonstrate these sorts of things, and in a fashion that does not presuppose that your position is correct.

SOME SUGGESTIONS FOR WRITING YOUR PHILOSOPHY PAPER

- Organize carefully. Before you start to write make an outline of how you want to argue. There should be a logical progression of ideas - one that will be easy for the reader to follow. If your paper is well organized, the reader will be led along in what seems a natural way. If you jump about in your essay, the reader will balk. It will take a real effort to follow you, and he or she may feel it not worthwhile. It is a good idea to let your outline simmer for a few days before you write your first draft. Does it still seem to flow smoothly when you come back to it? If not, the best prose in the world will not be enough to make it work.

- Use the right words. Once you have determined your outline, you must select the exact words that will convey your meaning to the reader. A dictionary is almost essential here. Do not settle for a word that (you think) comes close to capturing the sense you have in mind. Notice that "infer" does not mean "imply"; "disinterested" does not mean "uninterested"; and "reference" does not mean either "illusion" or "allusion." Make certain that you can use "its" and "it's" correctly. Notice that certain words such as "therefore," "hence," "since," and "follows from" are strong logical connectives. When you use such expressions you are asserting that certain tight logical relations hold between the claims in question. You had better be right. Finally, check the spelling of any word you are not sure of. There is no excuse for "existance" appearing in any philosophy essay.

- Support your claims. Assume that your reader is constantly asking such questions as "Why should I accept that?" If you presuppose that he or she is at least mildly skeptical of most of your claims, you are more likely to succeed in writing a paper that argues for a position. Most first attempts at writing philosophy essays fall down on this point. Substantiate your claims whenever there is reason to think that your critics would not grant them.

- Give credit. When quoting or paraphrasing, always give some citation. Indicate your indebtedness, whether it is for specific words, general ideas, or a particular line of argument. To use another writer's words, ideas, or arguments as if they were your own is to plagiarize. Plagiarism is against the rules of academic institutions and is dishonest. It can jeopardize or even terminate your academic career. Why run that risk when your paper is improved (it appears stronger not weaker) if you give credit where credit is due? That is because appropriately citing the works of others indicates an awareness of some of the relevant literature on the subject.

- Anticipate objections. If your position is worth arguing for, there are going to be reasons which have led some people to reject it. Such reasons will amount to criticisms of your stand. A good way to demonstrate the strength of your position is to consider one or two of the best of these objections and show how they can be overcome. This amounts to rejecting the grounds for rejecting your case, and is analogous to stealing your enemies' ammunition before they have a chance to fire it at you. The trick here is to anticipate the kinds of objections that your critics would actually raise against you if you did not disarm them first. The other challenge is to come to grips with the criticisms you have cited. You must argue that these criticisms miss the mark as far as your case is concerned, or that they are in some sense ill-conceived despite their plausibility. It takes considerable practice and exposure to philosophical writing to develop this engaging style of argumentation, but it is worth it.

- Edit boldly. I have never met a person whose first draft of a paper could not be improved significantly by rewriting. The secret to good writing is rewriting - often. Of course it will not do just to reproduce the same thing again. Better drafts are almost always shorter drafts - not because ideas have been left out, but because words have been cut out as ideas have been clarified. Every word that is not needed only clutters. Clear sentences do not just happen. They are the result of tough-minded editing.

There is much more that could be said about clear writing. I have not stopped to talk about grammatical and stylistic points. For help in these matters (and we all need reference works in these areas) I recommend a few of the many helpful books available in the campus bookstore. My favorite little book on good writing is The Elements of Style , by William Strunk and E.B. White. Another good book, more general in scope, is William Zinsser's, On Writing Well . Both of these books have gone through several editions. More advanced students might do well to read Philosophical Writing: An Introduction , by A.P. Martinich. Some final words should be added about proofreading. Do it. Again. After that, have someone else read your paper. Is this person able to understand you completely? Can he or she read your entire paper through without getting stuck on a single sentence? If not, go back and smooth it out. In general terms, do not be content simply to get your paper out of your hands. Take pride in it. Clear writing reflects clear thinking; and that, after all, is what you are really trying to show.

Undergraduate

Study philosophy at sfu, department events.

.................

Department News

Horban Award 2024: Nava Karimi June 12, 2024 The Department of Philosophy at Simon Fraser University would like to congratulate Nava Karimi, who...

Horban Award 2023: Danielle Jones July 04, 2023 The Department of Philosophy at Simon Fraser University would like to congratulate Danielle Jones,...

Horban Award 2023: Parmida Saemiyan July 04, 2023 The Department of Philosophy at Simon Fraser University would like to congratulate Parmida...

2023 BC Lower Mainland Ethics Bowl Report March 09, 2023 by Cem Erkli On February 25th, 150 high school students from all across the Lower Mainland met on...

Blended learning: spotlight on SFU’s newest course designation September 21, 2022 Philosophy Chair Evan Tiffany is one of the first faculty members at SFU to design and deliver a...

MA Student Aaron Richardson at Aesthetics For Birds - Accessibility and the Problem of Alt Text September 21, 2022

SFU Philosophy's collection of 'be employable, study philosophy' web content: PHIL IRL on Flipboard

2.6 Writing Philosophy Papers

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Identify and characterize the format of a philosophy paper.

- Create thesis statements that are manageable and sufficiently specific.

- Collect evidence and formulate arguments.

- Organize ideas into a coherent written presentation.

This section will provide some practical advice on how to write philosophy papers. The format presented here focuses on the use of an argumentative structure in writing. Different philosophy professors may have different approaches to writing. The sections below are only intended to give some general guidelines that apply to most philosophy classes.

Identify Claims

The key element in any argumentative paper is the claim you wish to make or the position you want to defend. Therefore, take your time identifying claims , which is also called the thesis statement. What do you want to say about the topic? What do you want the reader to understand or know after reading your piece? Remember that narrow, modest claims work best. Grand claims are difficult to defend, even for philosophy professors. A good thesis statement should go beyond the mere description of another person’s argument. It should say something about the topic, connect the topic to other issues, or develop an application of some theory or position advocated by someone else. Here are some ideas for creating claims that are perfectly acceptable and easy to develop:

- Compare two philosophical positions. What makes them similar? How are they different? What general lessons can you draw from these positions?

- Identify a piece of evidence or argument that you think is weak or may be subject to criticism. Why is it weak? How is your criticism a problem for the philosopher’s perspective?

- Apply a philosophical perspective to a contemporary case or issue. What makes this philosophical position applicable? How would it help us understand the case?

- Identify another argument or piece of evidence that might strengthen a philosophical position put forward by a philosopher. Why is this a good argument or piece of evidence? How does it fit with the philosopher’s other claims and arguments?

- Consider an implication (either positive or negative) that follows from a philosopher’s argument. How does this implication follow? Is it necessary or contingent? What lessons can you draw from this implication (if positive, it may provide additional reasons for the argument; if negative, it may provide reasons against the argument)?

Think Like a Philosopher

The following multiple-choice exercises will help you identify and write modest, clear philosophical thesis statements. A thesis statement is a declarative statement that puts forward a position or makes a claim about some topic.

- How does Aristotle think virtue is necessary for happiness?

- Is happiness the ultimate goal of human action?

- Whether or not virtue is necessary for happiness.

- Aristotle argues that happiness is the ultimate good of human action and virtue is necessary for happiness.

- René Descartes argues that the soul or mind is the essence of the human person.

- Descartes shows that all beliefs and memories about the external world could be false.

- Some people think that Descartes is a skeptic, but I will show that he goes beyond skepticism.

- In the meditations, Descartes claims that the mind and body are two different substances.

- Descartes says that the mind is a substance that is distinct from the body, but I disagree.

- Contemporary psychology has shown that Descartes is incorrect to think that human beings have free will and that the mind is something different from the brain.

- Thomas Hobbes’s view of the soul is materialistic, whereas Descartes’s view of the soul is nonphysical. In this paper, I will examine the differences between these two views.

- John Stuart Mill reasons that utilitarian judgments can be based on qualitative differences as well as the quantity of pleasure, but ultimately any qualitative difference must result in a difference in the quantity of pleasure.

- Mill’s approach to utilitarianism differs from Bentham’s by introducing qualitative distinctions among pleasures, where Bentham only considers the quantitative aspects of pleasure.

- J. S. Mill’s approach to utilitarianism aligns moral theory with the history of ethics because he allows qualitative differences in moral judgments.

- Rawls’s liberty principle ensures that all people have a basic set of freedoms that are important for living a full life.

- The US Bill of Rights is an example of Rawls’s liberty principle because it lists a set of basic freedoms that are guaranteed for all people.

- While many people may agree that Rawls’s liberty principle applies to all citizens of a particular country, it is much more controversial to extend those same basic freedoms to immigrants, including those classified by the government as permanent residents, legal immigrants, illegal immigrants, and refugees.

[ANS: 1.d 2.c 3.c 4.a 5.c]

Write Like a Philosopher

Use the following templates to write your own thesis statement by inserting a philosopher, claim, or contemporary issue:

- [Name of philosopher] holds that [claim], but [name of another philosopher] holds that [another claim]. In this paper, I will identify reasons for thinking [name of philosopher]’s position is more likely to be true.

- [Name of philosopher] argues that [claim]. In this paper, I will show how this claim provides a helpful addition to [contemporary issue].

- When [name of philosopher] argues in favor of [claim], they rely on [another claim] that is undercut by contemporary science. I will show that if we modify this claim in light of contemporary science, we will strengthen or weaken [name of philosopher]’s argument.

Collect Evidence and Build Your Case

Once you have identified your thesis statement or primary claim, collect evidence (by returning to your readings) to compose the best possible argument. As you assemble the evidence, you can think like a detective or prosecutor building a case. However, you want a case that is true, not just one that supports your position. So you should stay open to modifying your claim if it does not fit the evidence . If you need to do additional research, follow the guidelines presented earlier to locate authoritative information.

If you cannot find evidence to support your claim but still feel strongly about it, you can try to do your own philosophical thinking using any of the methods discussed in this chapter or in Chapter 1. Imagine counterexamples and thought experiments that support your claim. Use your intuitions and common sense, but remember that these can sometimes lead you astray. In general, common sense, intuitions, thought experiments, and counterexamples should support one another and support the sources you have identified from other philosophers. Think of your case as a structure: you do not want too much of the weight to rest on a single intuition or thought experiment.

Consider Counterarguments

Philosophy papers differ from typical argumentative papers in that philosophy students must spend more time and effort anticipating and responding to counterarguments when constructing their own arguments. This has two important effects: first, by developing counterarguments, you demonstrate that you have sufficiently thought through your position to identify possible weaknesses; second, you make your case stronger by taking away a potential line of attack that an opponent might use. By including counterarguments in your paper, you engage in the kind of dialectical process that philosophers use to arrive at the truth.

Accurately Represent Source Material

It is important to represent primary and secondary source material as accurately as possible. This means that you should consider the context and read the arguments using the principle of charity. Make sure that you are not strawmanning an argument you disagree with or misrepresenting a quote or paraphrase just because you need some evidence to support your argument. As always, your goal should be to find the most rationally compelling argument, which is the one most likely to be true.

Organize Your Paper

Academic philosophy papers use the same simple structure as any other paper and one you likely learned in high school or your first-year composition class.

Introduce Your Thesis

The purpose of your introduction is to provide context for your thesis. Simply tell the reader what to expect in the paper. Describe your topic, why it is important, and how it arises within the works you have been reading. You may have to provide some historical context, but avoid both broad generalizations and long-winded historical retellings. Your context or background information should not be overly long and simply needs to provide the reader with the context and motivation for your thesis. Your thesis should appear at the end of the introduction, and the reader should clearly see how the thesis follows from the introductory material you have provided. If you are writing a long paper, you may need several sentences to express your thesis, in which you delineate in broad terms the parts of your argument.

Make a Logical and Compelling Case Using the Evidence

The paragraphs that follow the introduction lay out your argument. One strategy you can use to successfully build paragraphs is to think in terms of good argument structure. You should provide adequate evidence to support the claims you want to make. Your paragraphs will consist of quotations and paraphrases from primary and secondary sources, context and interpretation, novel thoughts and ideas, examples and analogies, counterarguments, and replies to the counterarguments. The evidence should both support the thesis and build toward the conclusion. It may help to think architecturally: lay down the foundation, insert the beams of your strongest support, and then put up the walls to complete the structure. Or you might think in terms of a narrative: tell a story in which the evidence leads to an inevitable conclusion.

Connections

See the chapter on logic and reasoning for a developed account of different types of philosophical arguments.

Summarize Your Argument in the Conclusion

Conclude your paper with a short summary that recapitulates the argument. Remind the reader of your thesis and revisit the evidence that supports your argument. You may feel that the argument as written should stand on its own. But it is helpful to the reader to reinforce the argument in your conclusion with a short summary. Do not introduce any new information in the conclusion; simply summarize what you have already said.

The purpose of this chapter has been to provide you with basic tools to become a successful philosophy student. We started by developing a sophisticated picture of how the brain works, using contemporary neuroscience. The brain represents and projects a picture of the world, full of emotional significance, but this image may contain distortions that amount to a kind of illusion. Cognitive illusions produce errors in reasoning, called cognitive biases. To guard against error, we need to engage in effortful, reflective thinking, where we become aware of our biases and use logical strategies to overcome them. You will do well in your philosophy class if you apply the good habits of mind discussed in this chapter and apply the practical advice that has been provided about how to read and write about philosophy.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-philosophy/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Nathan Smith

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Introduction to Philosophy

- Publication date: Jun 15, 2022

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/introduction-philosophy/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/introduction-philosophy/pages/2-6-writing-philosophy-papers

© Mar 1, 2024 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

The Writing Place

Resources – how to write a philosophy paper, introduction to the topic.

The most common introductory level philosophy papers involve making an original argument (“Do you believe that free will exists?”) or thinking critically about another philosopher’s argument (“Do you agree with Hobbes’ argument about free will?”). This short checklist will help you construct a paper for these two types of assignments.

The Basics of a Philosophy Paper

1. introduction and thesis.

There is not a need for a grand or lofty introduction in a philosophy paper. Introductory paragraphs should be short and concise. In the thesis, state what you will be arguing and how you will make your argument.

2. Define Terms

It is important to define words that you use in your argument that may be unclear to your reader. While it may seem like words like “morality” and “free will” have an obvious definition, you need to make clear to your audience what those words mean in the context of your paper. A generally useful rule is to pretend that your reader does not know anything about your course or the subject of philosophy and define any words or concepts that such a reader may find ambiguous.

In a philosophy paper, you need to give reasons to support the argument you made in your thesis. This should constitute the largest portion of your paper. It is also important here to name preexisting conditions (premises) that must exist in order for the argument to be true. You can use real-world examples and the ideas of other philosophers to generate reasons why your argument is true. Remember to use simple and clear language and treat your readers as if they are not experts in philosophy.

4. Objections and Responses to Objections

Unlike other types of persuasive essays, in a many philosophy papers you should anticipate criticisms of your argument and respond to those criticisms. If you can refute objections to your argument, your paper will be stronger. While you do not have to address every potential counterargument, you should try to cover the most salient problems.

5. Conclusion

Like the introduction, you should be simple and concise. In the final paragraph you should review and summarize what your paper has established. The conclusion should tell readers why your argument is relevant. It answers the question, “Why do I care?”

General Tips

- Do not overstate or over generalize your ideas.

- Do not try to argue for both sides of an issue. Be clear about where you stand or your reader will be confused.

- Be specific. Do not try to tackle a huge issue, but rather, aim to discuss something small that can be done justice in just a few pages.

- Be wary of using religious or legal grounds for your argument.

A Quick Practice Exercise...

Practice: what is wrong with this paragraph.

This paragraph contains 5 major errors that you should try to avoid in a philosophy paper. Can you find them all?

“In his argument from design, Paley uses the example of a watch that he finds upon a road that has dozens of pieces that work together to make the clock function. He asserts that this watch is too perfect of a creation not to have a creator and that it would be obvious to conclude that the timepiece must have a maker. Similarly, the Bible proves that God must exist because he made the world beautiful in seven days. Paley notes, “There cannot be design without a designer; contrivance, without a contriver; order, without choice; arrangement without anything capable of arranging” (Paley 49). This reasoning is strong because it is apparent that beings found in nature have a complex design. For example, the iris, retina, lens and ocular muscles of the eye all work together to produce sight in the human eye and without any one of these mechanisms, one would be blind. For all of these tiny pieces that are required for a functioning eye to have randomly come together seems impossible. Therefore, it is logical that there had to be a designer who created a world in which DNA replicates and dozens of small parts create a functioning human or animal. By simply viewing the natural world, it is highly plausible to see that Paley’s theory is correct.”

1. “Similarly, the Bible proves that God must exist because he had the power to make the flood happen in Noah’s Ark.” Arguments based off religious texts, such as the Bible, are generally frowned upon and only weaken an essay.

2. The writer does not define what he means by “God.” Is God a benevolent overseer of the earth? Or is God a vengeful figure? Although it may seem as though everyone knows who God is, in reality, people have different perspective and the writer needs to define God’s character for the reader.

3. “For all of these tiny pieces that are required for a functioning eye to have randomly come together seems impossible.” The phrase “ seems impossible ” is weak and unclear. In a philosophy paper, you should take a strong stance and avoid words that weaken your argument like “probably” or “seem.” Additionally, the phrase “ highly plausible ” appears at the end of the paragraph, which is also a phrase that weakens the argument.

4. The writer gives not premises for Paley’s argument to be true. A stronger paper would name the preexisting conditions that must exist in order for the argument to stand.

5. The “real world” example of the human eye is not the best. The writer neglects strong counterarguments such as evolution and the existence of blindness in humans. A good philosophy paper would be more careful when considering real world examples.

Developed by Ann Bruton

Adapted from:

Harvard University’s Short Guide to Philosophical Writing

Kenneth Seeskin’s “How to Write a Philosophy Paper,” Northwestern University

Click here to return to the “Writing Place Resources” main page.

1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

Philosophy, One Thousand Words at a Time

How to Write a Philosophical Essay

Authors: The Editors of 1000-Word Philosophy [1] Category: Student Resources Word Count: 998

If you want to convince someone of a philosophical thesis, such as that God exists , that abortion is morally acceptable , or that we have free will , you can write a philosophy essay. [2]

Philosophy essays are different from essays in many other fields, but with planning and practice, anyone can write a good one. This essay provides some basic instructions. [3]

1. Planning

Typically, your purpose in writing an essay will be to argue for a certain thesis, i.e., to support a conclusion about a philosophical claim, argument, or theory. [4] You may also be asked to carefully explain someone else’s essay or argument. [5]

To begin, select a topic. Most instructors will be happy to discuss your topic with you before you start writing. Sometimes instructors give specific prompts with topics to choose from.

It’s generally best to select a topic that you’re interested in; you’ll put more energy into writing it. Your topic will determine what kind of research or preparation you need to do before writing, although in undergraduate philosophy courses, you usually don’t need to do outside research. [6]

Essays that defend or attack entire theories tend to be longer, and are more difficult to write convincingly, than essays that defend or attack particular arguments or objections: narrower is usually better than broader.

After selecting a topic, complete these steps:

- Ensure that you understand the relevant issues and arguments. Usually, it’s enough to carefully read and take notes on the assigned readings on your essay’s topic.

- Choose an initial thesis. Generally, you should choose a thesis that’s interesting, but not extremely controversial. [7] You don’t have to choose a thesis that you agree with, but it can help. (As you plan and write, you may decide to revise your thesis. This may require revising the rest of your essay, but sometimes that’s necessary, if you realize you want to defend a different thesis than the one you initially chose.)

- Ensure that your thesis is a philosophical thesis. Natural-scientific or social-scientific claims, such as that global warming is occurring or that people like to hang out with their friends , are not philosophical theses. [8] Philosophical theses are typically defended using careful reasoning, and not primarily by citing scientific observations.

Instructors will usually not ask you to come up with some argument that no philosopher has discovered before. But if your essay ignores what the assigned readings say, that suggests that you haven’t learned from those readings.

2. Structure

Develop an outline, rather than immediately launching into writing the whole essay; this helps with organizing the sections of your essay.

Your structure will probably look something like the following, but follow your assignment’s directions carefully. [9]

2.1. Introduction and Thesis

Write a short introductory paragraph that includes your thesis statement (e.g., “I will argue that eating meat is morally wrong”). The thesis statement is not a preview nor a plan; it’s not “I will consider whether eating meat is morally wrong.”

If your thesis statement is difficult to condense into one sentence, then it’s likely that you’re trying to argue for more than one thesis. [10]

2.2. Arguments

Include at least one paragraph that presents and explains an argument. It should be totally clear what reasons or evidence you’re offering to support your thesis.

In most essays for philosophy courses, you only need one central argument for your thesis. It’s better to present one argument and defend it well than present many arguments in superficial and incomplete ways.

2.3. Objection

Unless the essay must be extremely short, raise an objection to your argument. [11] Be clear exactly which part of the other argument (a premise, or the form) is being questioned or denied and why. [12]

It’s usually best to choose either one of the most common or one of the best objections. Imagine what a smart person who disagreed with you would say in response to your arguments, and respond to them.

Offer your own reply to any objections you considered. If you don’t have a convincing reply to the objection, you might want to go back and change your thesis to something more defensible.

2.5. Additional Objections and Replies

If you have space, you might consider and respond to the second-best or second-most-common objection to your argument, and so on.

2.6. Conclusion

To conclude, offer a paragraph summarizing what you did. Don’t include any new or controversial claims here, and don’t claim that you did more than you actually accomplished. There should be no surprises at the end of a philosophy essay.

Make your writing extremely clear and straightforward. Use simple sentences and don’t worry if they seem boring: this improves readability. [13] Every sentence should contribute in an obvious way towards supporting your thesis. If a claim might be confusing, state it in more than one way and then choose the best version.

To check for readability, you might read the essay aloud to an audience. Don’t try to make your writing entertaining: in philosophy, clear arguments are fun in themselves.

Concerning objections, treat those who disagree with you charitably. Make it seem as if you think they’re smart, careful, and nice, which is why you are responding to them.

Your readers, if they’re typical philosophers, will be looking for any possible way to object to what you say. Try to make your arguments “airtight.”

4. Citations

If your instructor tells you to use a certain citation style, use it. No citation style is universally accepted in philosophy. [14]

You usually don’t need to directly quote anyone. [15] You can paraphrase other authors; where you do, cite them.

Don’t plagiarize . [16] Most institutions impose severe penalties for academic dishonesty.

5. Conclusion

A well-written philosophy essay can help people gain a new perspective on some important issue; it might even change their minds. [17] And engaging in the process of writing a philosophical essay is one of the best ways to develop, understand, test, and sometimes change, your own philosophical views. They are well worth the time and effort.

[1] Primary author: Thomas Metcalf. Contributing authors: Chelsea Haramia, Dan Lowe, Nathan Nobis, Kristin Seemuth Whaley.

[2] You can also do some kind of oral presentation, either “live” in person or recorded on video. An effective presentation, however, requires the type of planning and preparation that’s needed to develop an effective philosophy paper: indeed, you may have to first write a paper and then use it as something like a script for your presentation. Some parts of the paper, e.g., section headings, statements of arguments, key quotes, and so on, you may want to use as visual aids in your presentation to help your audience better follow along and understand.

[3] Many of these recommendations are, however, based on the material in Horban (1993), Huemer (n.d.), Pryor (n.d.), and Rippon (2008). There is very little published research to cite about the claims in this essay, because these claims are typically justified by instructors’ experience, not, say, controlled experiments on different approaches to teaching philosophical writing. Therefore, the guidance offered here has been vetted by many professional philosophers with a collective hundreds of hours of undergraduate teaching experience and further collective hundreds of hours of taking philosophy courses. The editors of 1000-Word Philosophy also collectively have thousands of hours of experience in writing philosophy essays.

[4] For more about the areas of philosophy, see What is Philosophy? by Thomas Metcalf.

[5] For an explanation of what is meant by an “argument” in philosophy, see Arguments: Why Do You Believe What You Believe? by Thomas Metcalf.

[6] Outside research is sometimes discouraged, and even prohibited, for philosophy papers in introductory courses because a common goal of a philosophy paper is not to report on a number of views on a philosophical issue—so philosophy papers usually are not “research reports”—but to rather engage a specific argument or claim or theory, in a more narrow and focused way, and show that you understand the issue and have engaged in critically. If a paper engages in too much reporting of outside research, that can get in the way of this critical evaluation task.

[7] There are two reasons to avoid extremely controversial theses. First, such theses are usually more difficult to defend adequately. Second, you might offend your instructor, who might (fairly or not) give you a worse grade. So, for example, you might argue that abortion is usually permissible, or usually wrong, but you probably shouldn’t argue that anyone who has ever said the word ‘abortion’ should be tortured to death, and you probably shouldn’t argue that anyone who’s ever pregnant should immediately be forced to abort the pregnancy, because both of these claims are extremely implausible and so it’s very unlikely that good arguments could be developed for them. But theses that are controversial without being implausible can be interesting for both you and the instructor, depending on how you develop and defend your argument or arguments for that thesis.

[8] Whether a thesis is philosophical mostly depends on whether it is a lot like theses that have been defended in important works of philosophy. That means it would be a thesis about metaphysics, epistemology, value theory, logic, history of philosophy, or something therein. For more information, see Philosophy and Its Contrast with Science and What is Philosophy? both by Thomas Metcalf.

[9] Also, read the grading rubric, if it’s available. If your course uses an online learning environment, such as Canvas, Moodle, or Schoology, then the rubric will often be visible as attached to the assignment itself. The rubric is a breakdown of the different requirements of the essay and how each is weighted and evaluated by the instructor. So, for example, if some requirement has a relatively high weight, you should put more effort into doing a good job. Similarly, some requirement might explicitly mention some step for the assignment that you need to complete in order to get full credit.

[10] In some academic fields, a “thesis” or “thesis statement” is considered both your conclusion and a statement of the basic support you will give for that conclusion. In philosophy, your thesis is usually just that conclusion: e..g, “Eating meat is wrong,” “God exists,” “Nobody has free will,” and so on: the support given for that conclusion is the support for your thesis.

[11] To be especially clear, this should be an objection to the argument given for your thesis or conclusion, not an objection to your thesis or conclusion itself. This is because you don’t want to give an argument and then have an objection that does not engage that argument, but instead engages something else, since that won’t help your reader or audience better understand and evaluate that argument.

[12] For more information about premises, forms, and objections, see Arguments: Why do You Believe What You Believe? by Thomas Metcalf.

[13] For a philosophical argument in favor of clear philosophical writing, and guidance on producing such writing, see Fischer and Nobis (2019).

[14] The most common styles in philosophy are APA (Purdue Online Writing Lab, n.d.a) and Chicago (Purdue Online Writing Lab, n.d.b.).

[15] You might choose to directly quote someone when it’s very important that the reader know that the quoted author actually said what you claim they said. For example, if you’re discussing some author who made some startling claim, you can directly quote them to show that they really said that. You might also directly quote someone when they presented some information or argument in a very concise, well-stated way, such that paraphrasing it would take up more space than simply quoting them would.

[16] Plagiarism, in general, occurs when someone submits written or spoken work that is largely copied, in style, substance, or both, from some other author’s work, and does not attribute it to that author. However, your institution or instructor may define “plagiarism” somewhat differently, so you should check with their definitions. When in doubt, check with your instructor first.

[17] These are instructions for relatively short, introductory-level philosophy essays. For more guidance, there are many useful philosophy-writing guides online to consult, e.g.: Horban (1993); Huemer (n.d.); Pryor (n.d.); Rippon (2008); Weinberg (2019).

Fischer, Bob and Nobis, Nathan. (2019, June 4). Why writing better will make you a better person. The Chronicle of Higher Education .

Horban, Peter. (1993). Writing a philosophy paper. Simon Fraser University Department of Philosophy .

Huemer, Michael. (N.d.). A guide to writing. Owl232.net .

Pryor, Jim. (N.d.). Guidelines on writing a philosophy paper. Jimpryor.net .

Purdue Online Writing Lab. (N.d.a.). General format. Purdue Online Writing Lab .

Purdue Online Writing Lab. (N.d.b.). General format. Purdue Online Writing Lab .

Rippon, Simon. (2008). A brief guide to writing the philosophy paper. Harvard College Writing Center .

Weinberg, Justin. (2019, January 15). How to write a philosophy paper: Online guides. Daily Nous .

Related Essays

Arguments: Why do You Believe What You Believe? by Thomas Metcalf

Philosophy and its Contrast with Science by Thomas Metcalf

What is Philosophy? By Thomas Metcalf

Translation

Pdf download.

Download this essay in PDF .

Follow 1000-Word Philosophy on Facebook and Twitter and subscribe to receive email notifications of new essays at 1000WordPhilosophy.com .

Share this:.

- Writing & Research Conference

- UW Course Descriptions

- Support the Writing Program

University Writing Program

Columbian College of Arts & Sciences

A Guide to Writing Philosophy Papers

In some respects, writing an undergraduate-level philosophy paper is not unlike writing an undergraduate-level paper in any of the other humanities or social sciences. In fact, one could argue that philosophical writing should act as a model for writing in other disciplines. This is because one of the central aims of western philosophy, since its inception in Ancient Greece, almost two and a half millennia ago, has been to lay bare the structure of all forms of argument, and most undergraduate writing, in any subject, requires the use of argument to defend claims. However, there are also important differences between the writing styles appropriate to philosophical papers and papers in other subjects. Most notably, philosophy papers usually focus more on logical structure than on content: the point is not to synopsize exhaustive literature reviews, but, rather, to focus as much as possible on relatively narrow sets of claims, and investigate their logical inter-relations. Philosophers are less interested in exhaustive cataloging of the latest information on a topic, than in the relations of logical, argumentative support that well-established claims bear to each other, and to certain enduring, controversial claims, like the claim that God exists.

In the following, I provide a four-part guide to writing an undergraduate-level philosophy paper. First, I explain what philosophical arguments are, and how they can be evaluated. The point of any philosophy paper is to formulate and/or evaluate philosophical arguments, so this brief, rudimentary discussion is essential as a starting point. Second, I explain the structure and style appropriate for a philosophy paper. Third, I give students some ideas about how to choose a topic and formulate a writing plan appropriate to a philosophy paper. Fourth, and finally, I provide a short primer on logic, which can help students formulate and evaluate philosophical arguments.

Before proceeding, let me remark about the scope of this guide. Although it is intended as a guide to writing philosophy papers for any philosophy WID class, many philosophy instructors would disagree with at least some part of what follows. Western philosophy has been dominated by two divergent traditions for the last two hundred years or so: the “continental” tradition and the “analytic” or “Anglo-American” tradition. The former is associated primarily with philosophers from continental Europe, especially Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, Husserl, Heidegger, Sartre and Foucault. The latter is associated primarily with philosophers who worked in the UK and the US (though many of its most prominent representatives are German natives). Frege, Russell, Carnap, Austin, Grice, Strawson, and Quine, are among the most famous figures associated with this tradition. Although it is difficult to briefly characterize the difference between these two traditions, roughly speaking, while the analytic tradition takes logic, mathematics, and science as models for doing philosophy, the continental tradition is more literary and impressionistic in its approach to philosophical problems. I am trained in the analytic tradition, and the following writing guidelines reflect this. Thus, before using this as a guide to your philosophical writing, make sure that your class and instructor are in the analytic tradition. Although much of the advice I offer below is, I hope, relevant to classes in the continental tradition, it might also seriously misrepresent philosophical writing as understood from the continental perspective.

Even within the analytic tradition, there can be substantive disagreements about student writing. For example, a colleague who works in the analytic tradition read an earlier draft of this guide and was, for the most part, impressed; however, he disagreed with my view that external sources are better paraphrased than directly cited. Although I think most instructors working in the analytic tradition would agree with most of the guidelines I provide below, you should have your instructor skim them to make sure that he or she does not take exception to any of them. As a guide to an initial, rough, paper draft, the following is, I think, an invaluable resource. Subsequent drafts should incorporate specific comments from the instructor whose class you are taking.

1. Philosophical Arguments

Understanding Arguments

The point of a philosophical paper is to make and evaluate philosophical arguments. ‘Argument’ is a term of art in philosophy. It means more than a mere dispute. An argument, as philosophers use this term, is a set of claims, that is, a set of declarative sentences (sentences which can be true or false). One of the claims is the conclusion of the argument: that which the argument attempts to prove. The other claims are the premises of the argument: the reasons that are given in support of the conclusion. The conclusion is a relatively controversial claim that the author aims to establish on the basis of relatively uncontroversial premises. For example, St. Thomas Aquinas, the great medieval philosopher and theologian, famously provides five ways to prove the existence of God. The conclusion of Aquinas’s arguments is that God exists – a controversial claim. He tries to establish this conclusion on the basis of less controversial premises, e.g., that objects are in motion, that anything in motion must have been put in motion by a different thing already in motion, and that this chain of causes must begin at some point.

Because the construction and evaluation of arguments is the point of a philosophy paper, clarity, precision, and organization are of paramount importance. One cannot determine whether or not some set of premises supports a conclusion unless both premises and conclusion are formulated clearly and precisely. For example, consider the following argument: “Laws can be repealed by the legislature. Gravity is a law. Therefore, gravity can be repealed by the legislature.” On one level, this argument appears to make sense: it appears to have the same form as many sound arguments, like, “Beverages can be warmed in the microwave. Tea is a beverage. Therefore, tea can be warmed in the microwave.” However, there is obviously something wrong with the first argument. The problem is that the world “law” is used in two different senses: in the first premise and the conclusion, it means roughly the same as “social rule enacted by political means”, while in the second premise, it means roughly the same as “natural law”. Because the word “law”, as it is used in the second premise, means something entirely different from its use in the conclusion, the premise is of no relevance to the conclusion, and so, provides no logical support for it. This shows why it is so important to be as precise and clear as possible in philosophical writing. Words often mean different things in different contexts, and, unless their meaning is made as clear and precise as possible, it is impossible to tell whether or not the claims words are used to formulate support each other.

Organization is important to make clear the complex logical relations that different claims bear to each other. Consider Aquinas’s First Way to prove the existence of God, to which I allude above. The conclusion is that God exists. The premises are that objects are in motion, that objects can be put in motion only by other objects already in motion, that there is a chain of causes extending into the past, and that if this chain of causes were infinite then there would be no motion. But how, exactly, do these premises conspire to establish the conclusion that God exists? The key to answering this question is appreciating the structure or organization of the argument. The structure of philosophical arguments can often be captured in a kind of flow-chart diagram. Each ‘node’ is a claim (premise or conclusion), and links between nodes represent logical support. So, for example, in Aquinas’s First Way, the node which represents the premise that objects are in motion does not link directly to the node which represents the conclusion: how can the claim that objects are in motion, alone, give sufficient logical support for the claim that God exists? After all, atheists acknowledge that objects are in motion, yet deny that God exists.

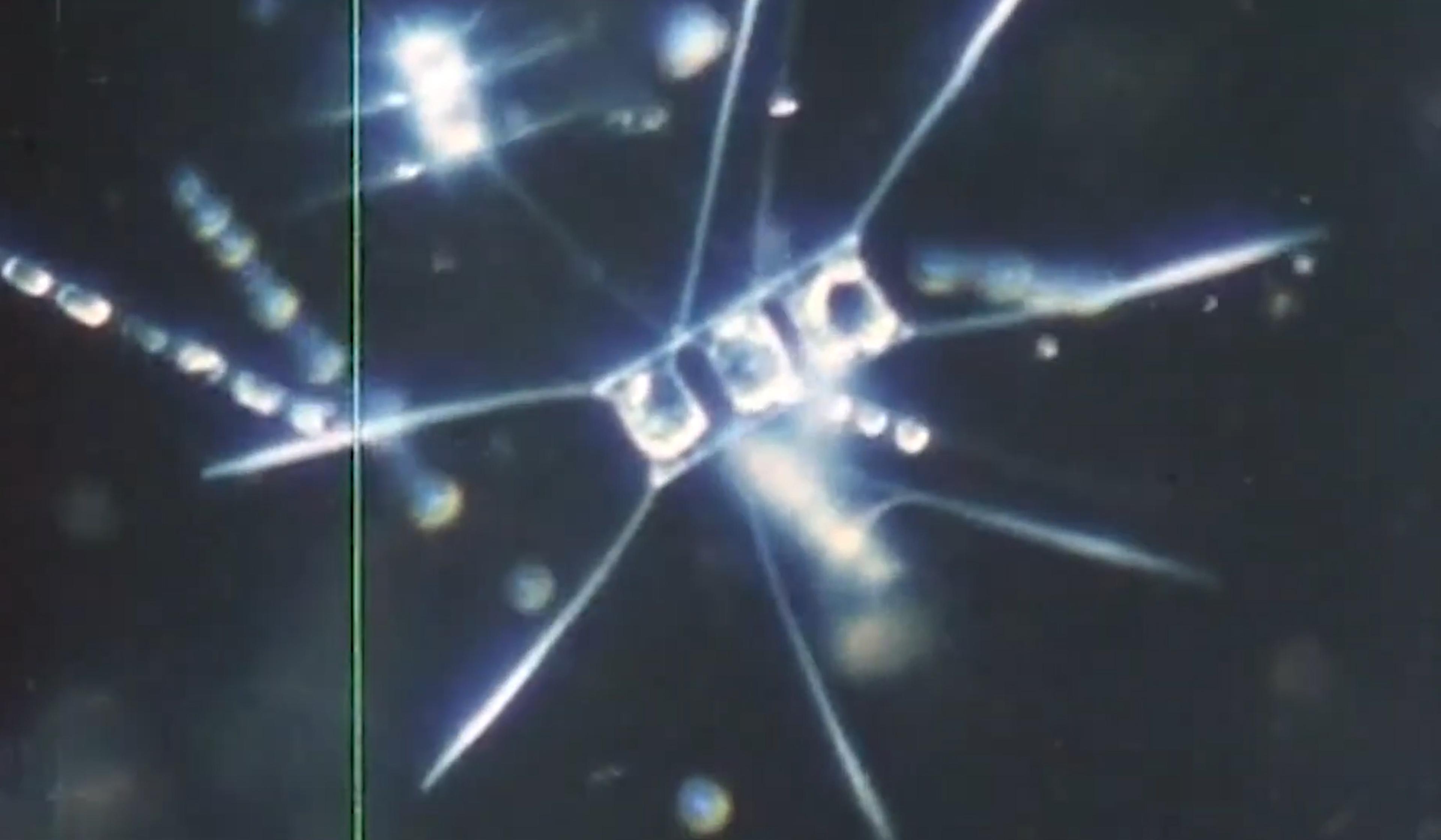

The structure of Aquinas’s First Way to prove the existence of God is approximated in the following diagram.

Note that the claim that objects are in motion (premise 1) must be joined with the claim that objects in motion are put in motion by other objects already in motion (premise 2), in order to support the claim that there is a causal chain of objects in motion extending into the past (premise 3), which constitutes the “sub-conclusion” of this “sub-argument”. Premise 3 must then be joined with premise 5 – the claim that this causal chain begins at some point – in order to support the claim that there is a first cause responsible for all the motion in the world, identified by Aquinas as God (premise 6). But premise 5 is not obvious on its own. It needs support from still other premises. For example, Aquinas claims that if there were no start to this chain of causes, none of the subsequent causes would occur (premise 4). Together with premise 1, premise 4 then supports premise 5, which, together with premises 3 and 6, supports the claim that there must be a first cause, namely, God (C). So premise 5 is another “sub-conclusion” of a “sub-argument”, which supports the ultimate conclusion (C).

The lesson from this example is that different claims have complicated relations of support to each other. Some premises support the conclusion only when conjoined with other premises. And other premises are like “sub-conclusions”, which must be supported by still other premises in “sub-arguments”, before they can be used to help establish the ultimate conclusion. Since the goal of writing an undergraduate philosophy paper is to formulate and evaluate arguments, organization is crucial. The author must make clear for the reader not just what the different premises and conclusions claim, but, also, how they relate to each other, that is, in what way they support each other.

Evaluating Arguments

There are only two ways that any argument can go wrong. An argument is good when its premises count as good reasons for its conclusion. What makes a premise a good reason for a conclusion? First, the premise must be true, or at least more plausible than the conclusion. For example, suppose I argue for the conclusion that Washington DC is likely the next home of the Stanley Cup champions on the basis of the following premises: the Bruins are likely the next Stanley Cup Champions, and they are based in Washington DC. This argument fails because at least one of its premises is false: the Bruins are based in Boston, not Washington DC. However, sometimes even true premises fail to qualify as good reasons for a conclusion. For example, suppose I argue for the conclusion that Washington DC is likely the next home of the Stanley Cup champions on the basis of the following premises: the Redskins are likely the next Superbowl Champions, and they are based in Washington DC. Here, the latter premise is true, and the previous premise may very well be true. However, the argument is still bad. The reason is that, even if these premises are true, they do not support the conclusion. The claims that the Redskins are likely the next Superbowl Champions and that the Redskins are based in Washington DC, are irrelevant to the conclusion: the claim that Washington DC is likely the next home of the Stanley Cup champions. So, there are two ways any argument can go wrong: either the premises it offers in support of its conclusion are false or implausible, or, even if they are true, they fail to support the conclusion because, for example, they are irrelevant to the conclusion.

Any philosophical writer must constantly keep these two potential pitfalls of argumentation in mind, both in formulating her own arguments and in evaluating the arguments of others. Undergraduate philosophy papers are often devoted exclusively to evaluating the arguments of well-known philosophers. Such critical papers must be guided by four basic questions: (1) What, precisely, do the premises and conclusion claim? (2) How, precisely, are the premises supposed to support the conclusion, i.e., what is the organization/structure of the argument? (3) Are the premises true/plausible? (4) Do the premises provide adequate support for the conclusion? Note that philosophical critiques of arguments seldom attack the conclusion directly. Rather, the conclusion is undermined by showing the premises to be false or implausible, or by showing that the premises, even if true, do not provide adequate support for the conclusion. Conclusions are attacked directly only on the grounds of imprecision or lack of clarity.

Despite the fact that arguments can be criticized on the grounds that their premises are false or implausible, most philosophical writing is focused not on determining the truth of premises, but, rather, on determining whether or not premises provide strong enough support for conclusions. There are three reasons for this. First, the most enduring philosophical arguments take as little for granted as possible: they rely on premises that are maximally uncontroversial – likely to be accepted by everyone – in order to prove conclusions that are controversial. Second, most philosophers have a strong background in logic. Logic is the science of argument: it aims to identify what all good arguments have in common and what all bad arguments have in common. But logic can be used only to evaluate the support that premises provide for a conclusion, never the truth or plausibility of the premises themselves. Any argument must take some claims as unargued starting points; otherwise, the argument could never get off the ground, as any premise would require a prior argument to be established. But logic can evaluate only arguments, so it cannot be used to evaluate the unargued starting premises with which any argument must begin. Third, the premises upon which many arguments depend often depend on observation, either in everyday life, or in specialized, scientific contexts such as experiments. But philosophers are not, for the most part, trained in experimental methodologies. They are trained in determining what follows logically from experimental results established in science or from common, everyday observations.

I discuss strategies for evaluating and formulating philosophical arguments in more detail below, in section 4. Now I turn to the structure and style appropriate for a philosophy paper.

2. Appropriate Structure and Style for a Philosophy Paper

Organizing the Paper

Although the philosophical canon includes a wide variety of styles and structures, including argumentative essays, axiomatically-organized systems of propositions, dialogs, confessions, meditations, historical narratives, and collections of aphorisms, most of these styles and structures are inappropriate for the novice, undergraduate, philosophical writer. Because the main concern of undergraduate philosophical writing is the formulation and evaluation of arguments, style and structure must be chosen with these goals in mind. As we have seen, precision, clarity, and organization are key to the understanding, formulation, and evaluation of arguments. If one’s language is not clear and precise, it is impossible to know what claims are being made, and therefore, impossible to determine their logical inter-relations. If one’s arguments are not clearly organized, it is difficult to determine how the different premises of an argument conspire to support its conclusion. As we saw above, with the example of Aquinas’ First Way to prove the existence of God, arguments are often composed of “sub-arguments” defending “sub-conclusions” that constitute premises in overall arguments. Unless such logical structure is perspicuously represented in a philosophy paper, the reader will lose track of the relevance that different claims bear to each other, and the paper will fail to enlighten the reader.

The best way to impose clarity and structure on a philosophy paper is to begin with a brief, clear, and concise introduction, outlining the organization of the rest of the paper. This introduction should be treated as a “map” of the rest of the paper that will prepare the reader for what is to follow. Alternatively, one may think of it as a “contract” with the reader: the author promises to discuss such and such related claims, in such and such an order. The introduction should make clear the logical inter-relations between the different claims that the paper will defend, and the order in which the claims will be discussed. With such an outline in hand, the writer can then organize the rest of the paper into numbered, sub-titled sub-sections, each devoted to the different parts of her argument, in the order outlined in the introduction. This helps maintain focus and clarity throughout the paper for the reader.

One of the greatest pitfalls in philosophical writing is distraction by tangential topics. Philosophical themes are extremely broad, and many of them are relevant to almost anything. So it is very tempting for a novice philosophical writer (and even for seasoned veterans) to stray from her original topic in the course of writing the paper. This throws the writer’s main goal – that of clearly articulating an argument capable of convincing a reader – into jeopardy; however, this danger can be avoided if the writer makes clear in the introduction exactly what components of a topic, and in what order, she intends to discuss and why, and then uses this to organize the rest of the paper. If the writer does this, readers should know exactly “where they are” in the overall argument, at any point in the paper, simply by noting the number and title of the sub-section they are reading, and referring to the introduction to understand its role in the paper’s overall argument.

A good introduction to a 10-page philosophy paper should take up no more than two-thirds of a page. It should accomplish three main objectives: (1) setting up the context for the paper, i.e., which philosophical debate or topic is the focus, (2) expressing the thesis of the paper, i.e., the conclusion it aims to defend, and (3) explaining, in broad terms, how the paper aims to defend this conclusion, i.e., what are the components of the argument, and in what order they will be discussed. The first objective, setting up the context, often requires reference to historically important philosophers known for defending claims related to the thesis of the paper. The components of the argument might include, first, an overview of how others have argued for or against the thesis, then a few sections on different assumptions made in these arguments, then a section in which the author provides her own argument for the thesis, and then a conclusion.

Consider the following example of an introduction to a paper about Aquinas’ First Way to prove the existence of God.

Aquinas, famously, provides five arguments for the existence of God. In the following, I focus on his First Way to prove the existence of God: the argument from motion. The claim that there can be no causal chains extending infinitely into the past plays a crucial role in this argument. In this paper, I argue against this claim, thereby undermining Aquinas’s First Way to prove the existence of God. First, I explain Aquinas’s argument, and the role that the claim about infinite causal chains plays in it. Second, I explain Aquinas’s defense of this claim. Third, I raise three objections to this defense. I conclude by drawing some broader lessons for the question of God’s existence.

Notice that, despite its brevity, this introduction is very specific and clear regarding what the author intends to accomplish in the paper. The thesis is stated clearly and concisely. Brief reference to Aquinas, his five proofs for the existence of God, and the specific proof on which the paper focuses provide necessary context. Specificity and clarity are aided further with the use of numbering. The reader knows to expect four sections following the introduction, and she knows exactly what each section will try to accomplish, and its role in the overall project of the paper. She knows to expect three objections to the argument that is the main target of the paper, in the third section after the introduction. And the writer can now easily structure the paper into five, numbered sub-sections (including the introduction), with appropriate titles, meant to periodically remind the reader of where she is in the overall argument.

When the writer starts with such a well-defined structure, it is relatively easy to avoid the pitfall of tangential distractions. Beginning with such an introduction is not meant to be unreasonably constraining. In the course of writing the paper, an author might revise her thinking about the topic, and be forced to reconceptualize the paper. She would then have to begin by revising the introduction, and, consequently, the organization of the paper. This is a natural part of paper revision. So, the introduction should not be treated as though it were written in stone. In early drafts, the introduction should serve as a provisional source of constraint for organizing one’s thoughts about the topic. As one’s thoughts evolve, the introduction can be rewritten, and the paper reorganized, to reflect this. But beginning with an introduction that specifies the organization of the paper in substantial detail serves as an important constraint on one’s writing and thinking, insuring that one’s topic is investigated systematically.

1. Plain Language for a Non-Specialist Audience: Much canonical philosophy is opaque and difficult to understand for the novice. A common reaction to this in undergraduate writing is the use of obscure “academic-sounding” language, of which students have only minimal mastery, in an attempt to sound intelligent and equal to the task of explaining and criticizing canonical philosophical arguments. This must be avoided at all costs. Good philosophy papers must employ clear, plain language, in short sentences and short, well-organized paragraphs. It is impossible to evaluate the cogency of arguments unless they are expressed in terms that are easily understood. Students must not assume that instructors know in what senses they intend esoteric, philosophical vocabulary, nor what lessons they have drawn from the sources they have been reading. Unless a student can express and defend claims using words with which they, and any educated layperson are familiar, it is doubtful that they fully understand these claims. Students should write for an imagined audience composed of family members, friends and acquaintances. They should use words that any educated, non-specialist would understand in order to explain the more opaque canonical arguments their papers discuss, and in order to formulate their own responses to these arguments. This attitude both insures that the language students use is clear and precise, and shows the instructor the degree to which students have understood the more opaque canonical arguments they discuss.

2. Illustration with Examples: One of the most important components of a good undergraduate philosophy paper is the copious use of concrete, everyday examples to illustrate abstract and sometimes obscure philosophical points. For example, the claim that a moving object must be put in motion by a different object already in motion is one of the key assumptions of Aquinas’s first argument for the existence of God. But this is a fairly abstract and potentially confusing way of expressing a familiar fact. Such abstract and potentially obscure means of expression are inevitable in philosophy because philosophers aim to defend maximally general conclusions: claims that are true in all circumstances, everywhere and always. In order to defend such general claims, familiar observations must be couched in the most general terms possible, and this often invites obscurity. Undergraduate philosophical writers must clarify such potentially confusing language by appeal to concrete, everyday examples.

For example, Aquinas’ claim about the causes of motion is actually a claim about the causes of any change in any object, including what we typically call “motion,” like a rolling ball, and other changes, like the rising temperature in a heated pan of water. A student should make this clear by illustrating Aquinas’s claim with such everyday examples. For example, one might write something like, “Aquinas claims that every moving or changing object is caused to move or change by a different object that is already in motion or changing. For example, a rolling ball is caused to move by a kick from a swinging foot, or a boiling pan of water is caused to boil by a flame giving off heat.” Such illustration of abstract philosophical principles with concrete, everyday examples serves two extremely important functions. First, it makes one’s exposition and evaluation of others’ arguments clear and tangible for the reader. Second, it shows one’s instructor that one has understood obscure yet crucial philosophical assumptions in one’s own terms.

3. The Principle of Charity: The point of any work of philosophy, from the most canonical treatise to the humblest undergraduate effort, is to determine which claims are supported by the best reasons. The point is not to persuade some particular audience of some claim using rhetoric. Philosophers always aim at identifying the best possible reasons to believe some claim. For this reason, when criticizing the arguments of others, philosophical writers should adhere to a principle of extreme charity. They should interpret arguments with which they disagree in the most favorable terms possible. Only then can they be sure that they have done their utmost to identify the truth of the matter. Criticism is inevitable in an undergraduate philosophy paper. In order to responsibly defend some conclusion, the student must give a thorough overview of what others have said about it, criticizing those with whom she disagrees. But students must bend over backwards to insure that these criticisms are fair. Since her goal is to arrive at the truth of the matter, a student author must not stack the deck against those with whom she disagrees. She must empathize with her antagonists; appreciating as deeply as possible the reasons why they disagree with the conclusion she defends. This puts the student author in a position to criticize those with whom she disagrees fairly and responsibly.

Consider, once more, Aquinas’s First Way to prove the existence of God. It is relatively easy to criticize this argument by appeal to modern physics. Aquinas assumes that every object in motion must have been put into motion by another object already in motion. But he was working with pre-Newtonian physics. According to post-Newtonian physics, an object can be in uniform motion without being acted upon by an outside force. So, technically, Aquinas’s premise is false. However, this is a nit-picky point that is unfair to Aquinas, and misses the spirit of his argument. Aquinas’s argument from motion can easily be rephrased as an argument from acceleration to make it compatible with post-Newtonian physics. Even if uniform motion does not require an external force, acceleration does, and once Aquinas’ premise is rephrased to respect this, the rest of the argument proceeds as before. Anyone seeking to criticize Aquinas’s argument is well served by considering the most charitable possible interpretation. If fatal flaws remain even after one has bent over backwards to accommodate Aquinas’s ignorance of later developments in physics, etc., one’s critique of his argument is more effective.

4. Self-Criticism: There is another implication of the philosopher’s commitment to discovering the claims that are supported by the best reasons, as opposed to just winning arguments. Works of philosophy must include self-criticism. The responsible philosophical author is always cognizant of potential pitfalls in her own arguments, and possible responses by antagonists she criticizes. In the course of criticizing an opposing view on some matter, a philosophical writer must always consider how her target might respond. In the course of defending some claim, a philosophical writer must always anticipate and respond to possible objections. Papers by professional philosophers often include whole sections devoted entirely to possible objections to the theses they defend. It is a good idea for undergraduate philosophical writers to follow this example: often, it is useful for the penultimate section of a paper to address possible criticisms of or responses to the arguments provided earlier in the paper. Not only does this constitute a fair and responsible way of writing philosophy, it helps the student think about her own views critically, improving the final product.

5. Undermining an Argument Vs. Criticizing a Conclusion: Suppose I raise some insurmountable problems for Aquinas’s first argument for the existence of God. It is important to keep in mind that this is not the same as arguing against the existence of God. Just because one argument for the existence of God fails, does not mean that there are not other arguments for the existence of God that succeed. Students should not think that criticizing an argument requires disagreeing with its conclusion. Some of the greatest critics of certain arguments for the existence of God were themselves theists. In fact, if you agree with the conclusion of a bad argument, it makes sense to criticize the argument, showing where it is weak; this can help you construct an alternative argument that avoids this problem. Criticizing an argument is never the same as arguing against its conclusion. To criticize an argument is to show that its premises do not provide adequate support for its conclusion, not to show that its conclusion is false. In order to do the latter, one must provide a new argument that supports the claim that the conclusion is false. For example, in order to show that God does not exist, it is not enough to show that no arguments for God’s existence are sound; one must also provide positive reasons to deny God’s existence.

An analogy to criminal trials makes this distinction clear. The goal of the prosecution in a criminal trial is to prove that the defendant is guilty. They must construct an argument that provides good reasons for this conclusion. However, the goal of the defense in a criminal trial is not to prove that the defendant is innocent. Rather, the defense aims to criticize the prosecution’s argument, to show that the reasons provided by the prosecution for the conclusion that the defendant is guilty are not strong enough to support this conclusion, because there remains a reasonable doubt that this conclusion is true. The difference between the tasks of the prosecution and the defense in a criminal trial parallels the distinction between arguing against (or for) a conclusion, and merely criticizing an argument for a conclusion. Students should keep this distinction in mind when writing philosophy papers. When they are defending any conclusion, e.g., that God exists or that God does not exist, they must provide arguments for this conclusion, much as the prosecution must provide evidence and reasons that prove the defendant guilty. When students are criticizing an argument, they are not defending the denial of the argument’s conclusion. Rather, like the defense in a criminal trial, they are merely undermining the reasons given for the conclusion.

6. References: Undergraduate philosophy papers must be grounded in relevant and reputable philosophical literature. Attributing claims to others, including canonical philosophers or discussions of them in the secondary literature, must be supported by references to appropriate sources. However, direct quotation should, on balance, be avoided. Instructors are interested in whether or not students understand difficult philosophical concepts and claims in their own terms. For this reason, paraphrase is usually the best way to cite a source. Using one’s own words to express a point one has read elsewhere, however, does not excuse one from referring to one’s source. Any time a substantial claim is attributed to another person, whether or not one uses the person’s own words, the source should be referenced. There are occasions when direct quotations are appropriate, for example, when one is defending a controversial interpretation of some philosopher’s argument, and the precise wording of her claims is important.