Table of contents

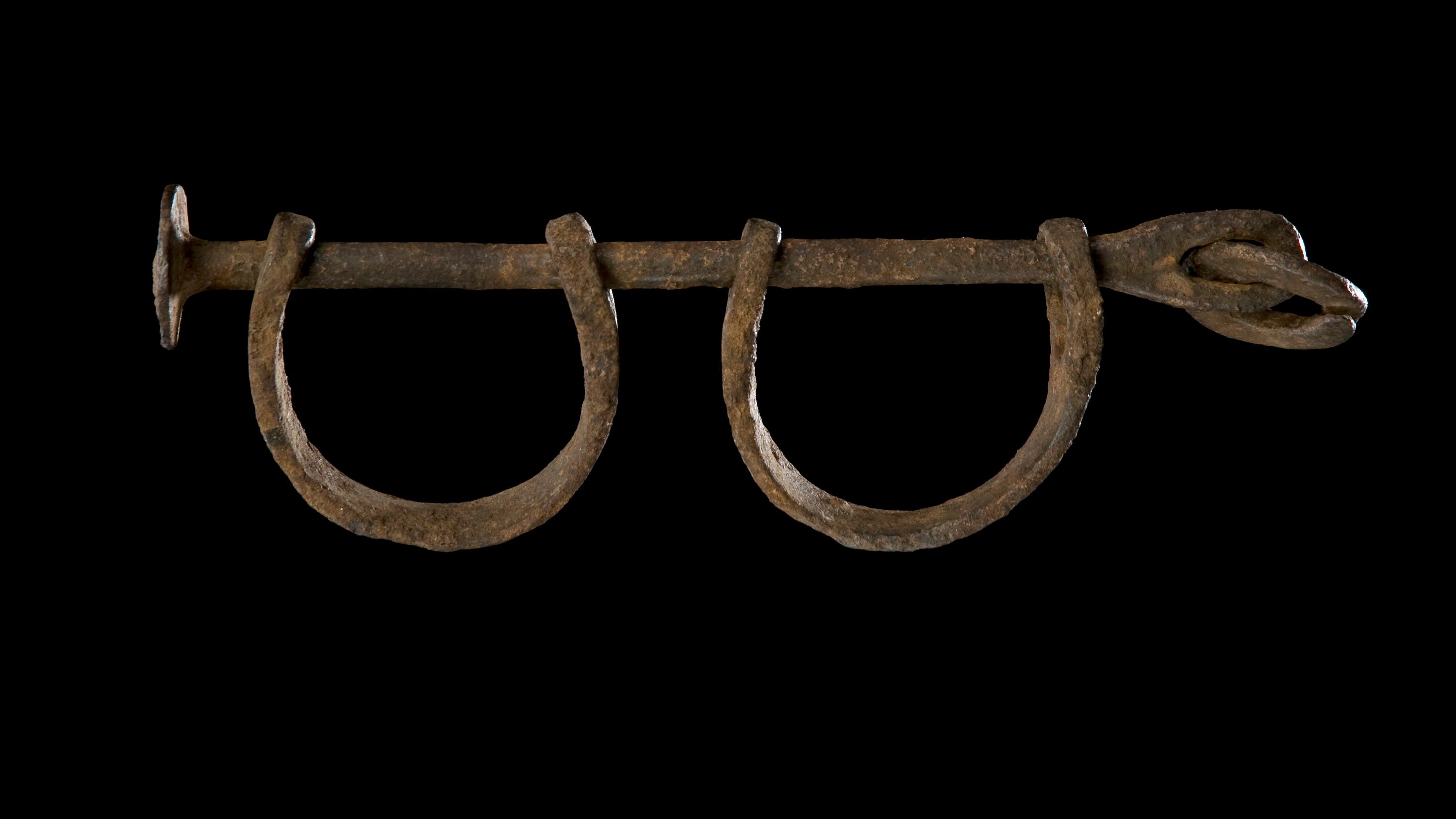

Slavery and its legacies before and after the civil war.

During the antebellum era, well after the end of slavery in Massachusetts, and even after the 13th Amendment to the US Constitution conferred emancipation nationwide in 1865, vestiges—or legacies—of the system lingered. Legacies of slavery such as exclusion, segregation, and discrimination against Blacks in employment, voting, housing, healthcare, public accommodations, criminal punishment, and education, among other areas, persisted in the South as well as the North. Go to footnote 38 detail Notwithstanding the Commonwealth’s Revolutionary War heritage as birthplace of the colonists’ struggle for liberty, its celebrated antislavery activists, and its many brave Union veterans of the Civil War, Go to footnote 39 detail racial inequality flourished in Massachusetts—and at Harvard—as Blacks struggled for equal opportunity and full citizenship. Go to footnote 40 detail

Slavery and Antislavery before the Civil War

In the years before the Civil War, the color line held at Harvard despite a false start toward Black access. In 1850, Harvard’s medical school admitted three Black students but, after a group of white students and alumni objected, the School’s dean, Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr., expelled them. Go to footnote 41 detail The episode crystallized opposition to Black students on campus, which outweighed the views of a vocal contingent of white classmates who supported the admission of the three African American students. Go to footnote 42 detail Over 100 years would pass before these more welcoming attitudes toward Blacks would prevail and open the door to significant Black enrollment.

The passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, requiring the return of enslaved people to their owners, even if slaves had escaped to free states, turned more white Northerners against slavery and its cruelties. Go to footnote 43 detail Yet support for antislavery efforts remained anemic at Harvard, even amid the rise of abolitionist sentiment in the Commonwealth. In some cases, University leadership even attempted to suppress abolitionist sentiment.

Within the context of increasing political rancor and social division on and off campus, a small but vocal group of Harvard affiliates pressed the abolitionist cause. In addition to Charles Sumner, outspoken abolitionist voices included Wendell Phillips (AB 1831; LLB 1834), founder of the New England Antislavery Society; John Gorham Palfrey (AB 1815; dean and faculty member, 1830–1839; overseer, 1828–1831, 1852–1855), the first dean of the Divinity School; and several other faculty members, among them cofounders of the Cambridge Anti-Slavery Society. Go to footnote 44 detail Richard Henry Dana Jr. (AB 1837; LLB 1839; lecturer 1866–1868; overseer, 1865–1877) cofounded the antislavery Free Soil party and represented Anthony Burns, a fugitive slave who had been arrested in Boston. In a turn of events decried by many Northerners, a Massachusetts judge, himself a Harvard alumnus and lecturer, ordered Burns returned to slavery in Virginia. Go to footnote 45 detail Because of such controversies, the Fugitive Slave Act became a catalyst of the Civil War, and by the time war began in 1861, the University officially supported the Union. Many Harvard men fought and died for the Union, and their sacrifices are commemorated on campus in Memorial Hall; some also fought and died for the Confederacy. Go to footnote 46 detail

Intellectual Leadership

Harvard’s ties to the legacies of slavery also include, prominently, its intellectual production—its scholarly leadership and the influential output of some members of its faculty. In the 19th century, Harvard had begun to amass human anatomical specimens, including the bodies of enslaved people, that would, in the hands of the University’s prominent scientific authorities, become central to the promotion of so-called race science at Harvard and other American institutions. Go to footnote 47 detail Charles William Eliot—Harvard’s longest-serving president—and several prominent faculty members promoted eugenics, the concept of selective reproduction premised on innate differences in moral character, health, and intelligence among races. Go to footnote 48 detail These were ideas of the sort that had long been deployed to justify racial segregation and which would in the 19th and 20th centuries cement profound racial inequities in the United States and underpin Nazi Germany’s extermination of “undesirable” populations. Go to footnote 49 detail In addition to research in the University’s extensive collections of human remains, Eliot authorized anthropometric measurements of Harvard’s own student-athletes. Go to footnote 50 detail Many of the records and artifacts of this era remain in the University’s collections today. Go to footnote 51 detail

Vestiges of Slavery after the Civil War

The decades after the Civil War, during the period of Reconstruction when debates raged about whether and how to support the Black American quest for equality, are especially germane to understanding legacies of slavery in American institutions of higher education. The US Constitution changed, reflecting the nation’s formal break with slavery and commitment to equal citizenship rights regardless of race. The 14th Amendment, conferring equal protection and due process of law, and the 15th Amendment, prohibiting discrimination against males in voting, were enacted and ratified. Go to footnote 52 detail Within this context, reformers conceived policies and social supports to lift the formerly enslaved and their descendants. But it fell to the nation’s institutions, its leadership, and its people to safeguard—or not—citizens’ rights and implement these policies. Go to footnote 53 detail

Around the same time, Harvard itself aspired to transform: it sought to enlarge its infrastructure, expand its student body, and recruit new faculty. Samuel Eliot Morison, a noted historian of the University, explained that during the period from 1869 into the 20th century, the University resolved “to expand with the country.” Go to footnote 54 detail Harvard’s leaders, particularly Presidents Charles William Eliot and Abbott Lawrence Lowell, argued that Harvard should become a “true” national university that would serve as a “unifying influence.” Go to footnote 55 detail They viewed the recruitment of students from “varied” backgrounds and a “large area” of the country as a linchpin of these ambitions. Go to footnote 56 detail

Hence, two developments critical to understanding this moment of promise and peril occurred at once: The fate of African Americans hung in the balance. And Harvard, already well-known, sought to grow, evolve, and build a yet greater national reputation.

The University, as a prominent institution of higher education, held influence in a sphere deemed particularly critical to racial uplift. Because so many considered education “a liberating force,” legislative and philanthropic efforts to create opportunity for African Americans often emphasized schooling. Go to footnote 57 detail Massachusetts was already a leader in this area; in addition to its many universities, the state had led the movement to establish taxpayer-supported “common schools” at the elementary and secondary levels. Go to footnote 58 detail

Nevertheless, in Massachusetts and in every corner of the nation, African Americans encountered roadblocks to achieving social mobility through education. White opposition to racially “mixed” schools, born of racist attitudes about Black ability and character promoted by slaveholders as well as intellectuals at Harvard and elsewhere, blocked equal access to education. Go to footnote 59 detail Segregated, under-resourced, and often inferior elementary and secondary schools became the norm for African Americans. In this, too, Massachusetts led the way.

Harvard alumni played prominent roles on both sides of the struggle over school segregation. One critically important chapter in that struggle, which would have dire nationwide consequences for Blacks into the 20th century, had occurred in Boston before the Civil War. In Roberts v. City of Boston , an 1850 decision, the Commonwealth helped normalize segregated schools. In that case—filed by Charles Sumner on behalf of a five-year-old Black girl—the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court held that racial segregation in the city’s schools did not offend the law. Go to footnote 60 detail Judge Lemuel Shaw (AB 1800; overseer, 1831–1853; fellow, 1834–1861) authored the opinion for the court. Go to footnote 319 detail “[T]he good of both classes of school will be best promoted, by maintaining the separate primary schools for colored and for white children,” he wrote. Go to footnote 745 detail Advocacy by the local Black community with important support from Sumner led the Commonwealth to ban segregated schools in 1855, the first such law in the United States. Go to footnote 734 detail Nevertheless, decades later, in 1896, the US Supreme Court cited Roberts as authority when it held in Plessy v. Ferguson that racially “separate but equal” facilities did not violate the 14th Amendment to the Constitution. Go to footnote 61 detail

In higher education, Blacks also found themselves in separate and unequal schools. It was left to historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs), supported by the federal government beginning in 1865 and often founded by Black self-help organizations and religious societies, to provide a measure of opportunity. Go to footnote 62 detail But from the start, HBCUs were sorely underfunded, a reality that hobbled school leaders as they sought to fulfill the HBCUs’ mission of racial uplift through postsecondary school access. Go to footnote 63 detail

Predominantly white universities did not fill the breach. In keeping with prevailing racial attitudes and the relegation of African Americans to poorly resourced HBCUs of uneven quality, Harvard—like all but a few white universities—did relatively little to support the African American quest for advancement. Go to footnote 64 detail

In the decades following the Civil War, at Harvard and other white universities, Blacks still faced discrimination, or plain indifference. Notwithstanding Harvard’s rhetorical commitment in the war’s wake to recruit a nationally representative student body that would model political collegiality, the University’s sights remained set on a white “upper crust.” Harvard prized the admission of academically able Anglo-Saxon students from elite backgrounds—including wealthy white sons of the South—and it restricted the enrollment of so-called “outsiders.” Go to footnote 65 detail Despite access to civic organizations in major cities that could identify a pool of able Black students, the college enrolled meager numbers of African Americans. Go to footnote 66 detail During the five decades between 1890 and 1940, approximately 160 Blacks attended Harvard College, or an average of about 3 per year, 30 per decade. Go to footnote 67 detail The pattern of low enrollment of Blacks also held true at Radcliffe College, Go to footnote 70 detail founded in 1879 as the “women’s annex” to all-male Harvard. Go to footnote 71 detail Radcliffe did consistently enroll more Black women than its Seven Sisters peers. Go to footnote 72 detail Yet the women educated at Radcliffe overwhelmingly were white, and Black women were denied campus housing. Go to footnote 73 detail

Those Blacks who did manage to enter Harvard’s gates during the 19th and early-to-mid 20th century excelled academically, earning equal or better academic records than most white students, Go to footnote 74 detail but encountered slavery’s legacies on campus. Two examples illustrate the segregation and marginalization that the few Black Harvard students faced: Go to footnote 75 detail First, Harvard President Abbott Lawrence Lowell’s signature innovation—a residential college experience for first years that was meant to build community—excluded the handful of Black Harvard students. Go to footnote 76 detail Lowell’s exclusionary policy was eventually overturned by the University’s governing boards following press attention and pressure from students, alumni, and activists. Go to footnote 77 detail Second, Black Harvard athletes, whose talents sometimes earned them respect and recognition from other students on campus, encountered discrimination and exclusion in intercollegiate play, and Harvard administrators sometimes bowed to it. Go to footnote 78 detail Yet Black students generally could and did participate in campus clubs and activities—illustrating a “half-opened door,” as one author termed the Ivy League experience of African Americans and, for a time, Jewish and other students from disfavored white ethnic backgrounds. Go to footnote 79 detail

The University’s history is complex, and its record of exclusion—not only along lines of race but also ethnicity, gender, and other categories—is clear and damaging. Yet this report does not explore the entirety of that difficult history; nor does it discuss at length the significance of Indigenous history to Harvard’s evolution, beyond colonial era dispossession and enslavement. This report focuses specifically on Harvard’s involvement with slavery and its legacies, from the colonial period into the 20th century, which is distinct in both degree and kind: Harvard’s very existence depended upon the expropriation of land and labor—land acquired through dispossession of Native territories and labor extracted from enslaved people, including Native Americans and Africans brought to the Americas by force. And, long after the official end of slavery, intellectual clout of influential Harvard leaders and distinguished faculty would be a powerful force justifying the continued subjugation of Black Americans.

Hence, the truth— Veritas —is that for hundreds of years, both before and after the Civil War, racial subjugation, exclusion, and discrimination were ordinary elements of life off and on the Harvard campus, in New England as well as in the American South. Abolitionist affiliates of the University did take a stand against human bondage, and others fought for racial reform after slavery. The willingness of these Harvard affiliates to speak out and act against racial oppression is rightly noted and celebrated. Go to footnote 80 detail But these exceptional individuals do not reflect the full scope of the University’s history. The nation’s oldest institution of higher education—“America’s de facto national university,” as a noted historian described it—helped to perpetuate the era’s racial oppression and exploitation. Go to footnote 81 detail

See Section IV of this report, and Sollors et al., eds., Blacks at Harvard, xix, 3, 22; Ronald Takaki, “Aesculapius Was a White Man: Antebellum Racism and Male Chauvinism at Harvard Medical School,” Phylon 32, no. 2 (1978): 128 – 134; Doris Y. Wilkinson, “The 1850 Harvard Medical School dispute and the admission of African American students,” Harvard Library Bulletin 3, no. 3 (Fall 1992): 13 – 27; see also Nora N. Nercessian, Against All Odds: The Legacy of Students of African Descent at Harvard Medical School before Affirmative Action, 1850–1968 (Hollis, NH: Puritan Press, 2004).

Wilkinson, “1850 Harvard Medical School,” 14, 16.

See Carla Bosco, “Harvard University and the Fugitive Slave Act,” New England Quarterly: A Historical Review of New England Life and Letters 79, no. 2 (2006): 227–247.

Bosco, “Fugitive Slave Act,” 229–230, 239. See Section IV of this report.

Bosco, “Fugitive Slave Act,” 242–243.

The names of Harvard men who died in service to the Union are displayed in Memorial Hall. See Morison, Three Centuries of Harvard , 302–303.

See Section IV of this report.

Adam S. Cohen, “Harvard’s Eugenics Era,” Features, Harvard Magazine , March-April 2016, https://www.harvardmagazine.com/2016/03/harvards-eugenics-era .

Charles Patton Blacker, Eugenics: Galton and After (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1952). On eugenics and Nazi Germany’s extermination campaigns, see Morton A. Aldrich et al., Eugenics: Twelve University Lectures (New York, NY: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1914).

See Section V of this report.

Because of universities’ unique role as sites of research and education, the idea of intellectual leadership as a category of entanglement and a form of culpability with slavery is particularly important. Yet it is also a complicated matter: Many universities rightly prize intellectual freedom, and therefore strive not to proscribe or circumscribe the intellectual output of their faculty. Harvard is no exception in this regard, and the discussion of past wrongs is not a departure from this core institutional value. It affirms academic freedom: As this report documents, rather than upholding the principle of academic freedom and the pursuit of Veritas , the University, on several occasions, sought to moderate or suppress anti-slavery views within the community.

Moreover, the committee does not propose a retrospective evaluation of all the ideas that have emerged from Harvard and may have caused harm. Rather, this report describes specific actions and ideas advanced by Harvard faculty and leaders with the University’s institutional backing—actions and ideas that caused enduring harm, and which we, as a University community, must no longer honor.

See U.S. Const. amends. XIII, XIV, XV; see also Eric Foner, “What is Freedom? The Thirteenth Amendment,” chap. 1, “Toward Equality: The Fourteenth Amendment,” chap. 2, and “The Right to Vote: The Fifteenth Amendment,” chap. 3 in The Second Founding: How the Civil War and Reconstruction Remade the Constitution (New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company, 2019).

On the white vigilante violence that followed formerly enslaved Blacks when they tried to exercise their newly found freedom, see Foner, Reconstruction 119–123, 425–430. W. E. B. Du Bois, Black Reconstruction in America: An Essay Toward a History of the Part Which Black Folk Played in the Attempt to Reconstruct Democracy in America, 1860 – 1880 (New York, NY: Russell & Russell, 1935), 221–230, describes, for example, the insufficient resources given to the Freedmen’s Bureau, a federal agency design to aid the formerly enslaved in the South, as the result of political pushback from Southern whites.

Morison, Three Centuries of Harvard , 323.

This language is drawn from an address by Charles William Eliot, president of Harvard from 1869–1909, quoted in Morison, Three Centuries of Harvard , 322.

Morison, Three Centuries of Harvard , 322. On the Overseers’ aspirations for Harvard during this period, see also Morison, 324–331.

Bobby L. Lovett, America’s Historically Black Colleges and Universities: A Narrative History, 1837 – 2009 (Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 2011), 5.

Wayne J. Urban and Jennings L. Wagoner, Jr., American Education: A History (New York, NY: Routledge, 2009), 116–127. On higher education in the Commonwealth, see George Gary Bush, History of Higher Education in Massachusetts (Washington, DC: G.P.O., 1891).

See Lovett, Black Colleges and Universities , 4–5; Urban and Wagoner, Jr., American Education , 167–168.

Roberts v. City of Boston, 59 Mass. 198, 5 Cush. 198 (1849). See David Herbert Donald, Charles Sumner and the Coming of the Civil War (Naperville, IL: Sourcebooks, Inc., 2009), 151. Sumner asserted: “The separation of the schools, so far from being for the benefit of both races, is an injury to both.” See also Roberts , 59 Mass. at 204.

“Lemuel Shaw,” Commonwealth of Massachusetts, accessed February 17, 2022, https://www.mass.gov/person/lemuel-shaw-0 ; Roberts , 59 Mass. at 209 (1850).

Roberts , 59 Mass. at 209.

See Carleton Mabee, “A Negro Boycott to Integrate Boston Schools,” New England Quarterly 41, no. 3 (September 1968): 341–361.

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 544 (1896) (Harlan, J., dissenting) coined the oft-quoted phrase “separate but equal”; see also Plessy, 544–545 (discussing Roberts ); Douglas J. Ficker, “From Roberts to Plessy : Education Segregation and the ‘Separate But Equal’ Doctrine,” The Journal of African American History 84, no. 4 (1999): 301–314. Even philanthropists who aided schools supported the practice of racial segregation and systematically provided less funding to southern Black schools. See Urban and Wagoner Jr., American Education , 166–171.

For a discussion on racial segregation in elementary and secondary education, see Urban and Wagoner, Jr., American Education , 165–168; for HBCUs, see generally Lovett, Black Colleges and Universities .

See Lovett, Black Colleges and Universities , xii–xiii; James D. Anderson, Education of Blacks in the South, 1860 – 1935 (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1988), 239, 248–249; Walter R. Allen et al., “Historically Black Colleges and Universities: Honoring the Past, Engaging the Present, Touching the Future,” The Journal of Negro Education 76, no. 3 (2007): 263, 267.

There was little support for mixed schools anywhere in the North. See Urban and Wagoner, Jr., American Education , 165; Sollors et al., eds., Blacks at Harvard , 1–4; West, “Harvard and the Black Man.”

On the exclusion of “outsiders,” see Marcia Graham Synnott, The Half-Opened Door: Discrimination and Admissions at Harvard, Yale, and Princeton, 1900–1970 (New York, NY: Routledge, 2010), 38; on preference for the “upper crust,” see Jerome Karabel, The Chosen: The Hidden History of Admission and Exclusion at Harvard, Yale, and Princeton (New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2005), 188, 199, 206, 255. Karabel discusses those excluded in greater detail at 39–41, 49–52, and chap. 3, “Harvard and the Battle Over Restriction.”

Synnott, The Half-Opened Door , 38, 40, 47, 207-208, 220; Sollors et al., eds., Blacks at Harvard , 2-3.

Synnott, The Half-Opened Door , 47.

See Muriel Spence, “Minority Women at Radcliffe: Talent, Character, and Endurance,” Radcliffe Quarterly 72, no. 3 (September 1986): 20–22, https://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:RAD.ARCH:4609952?n=130 .

Morison, Three Centuries of Harvard , 391–392.

Linda M. Perkins, “The African American Female Elite: The Early History of African American Women in the Seven Sister Colleges, 1880–1960,” Harvard Educational Review 67, no. 4 (December 1997): 726–729. Like the history of women at Harvard generally, the history of women of color at Harvard and Radcliffe has seldom been a subject of description or analysis. See Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, ed., Yards and Gates: Gender in Harvard and Radcliffe History (New York, NY: Palgrave, 2004), and Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, “Harvard’s Womanless History: Completing the University’s Self-Portrait,” Features, Harvard Magazine , December 18, 2018, https://www.harvardmagazine.com/2018/12/harvards-womanless-history .

See Perkins, “African American Female Elite,” 729; Morison, Three Centuries of Harvard , 392. The pattern of limited Black enrollment at Harvard and Radcliffe persisted into the mid-1960s. See Section V of this report.

Sollors et al., eds., Blacks at Harvard , xxi-xxiii; Perkins, “African American Female Elite,” 728–729.

See Nell I. Painter, “Jim Crow at Harvard: 1923,” The New England Quarterly 44, no. 4 (1971): 627–634; Sollors et al., eds., Blacks at Harvard , xxi–xxiii; Synnott, The Half-Opened Door , 49–50. For more on this controversy during the Lowell presidency, see Section V of this report.

Raymond Wolters, “The New Negro on Campus,” in Blacks at Harvard , 195–202. See also “Attacks Harvard On Negro Question: J. Weldon Johnson Denounces the Exclusion of Negroes From Its Dormitories,” New York Times , January 13, 1923, https://nyti.ms/3nJaq96 .

Synnott, The Half-Opened Door , 48–49.

Synnott, The Half-Opened Door , 47; on his exclusion from the glee club and social marginalization, see W. E. B. Du Bois, “A Negro Student at Harvard at the End of the 19th Century,” Massachusetts Review 1, no. 5 (May 1960): 439–458.

Richard Norton Smith, The Harvard Century: The Making of a University to a Nation (New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, 1986), 13.

For scholarship discussing the many laws, policies, practices, norms, and attitudes that remained as relics of slavery despite its legal prohibition, see generally Leon F. Litwack, Been in the Storm So Long: The Aftermath of Slavery (New York, NY: Knopf, 1979); Tera W. Hunter , To ‘Joy My Freedom: Southern Black Women’s Lives and Labors after the Civil War (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997); Kate Masur, An Example for All the Land: Emancipation and the Struggle over Equality in Washington, DC (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2010), 214–256; Eric Foner, Forever Free: The Story of Emancipation and Reconstruction (New York, NY: Knopf, 2005), 189–213; John Hope Franklin, Reconstruction: after the Civil War (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1961); Ariela J. Gross, What Blood Won’t Tell: A History of Race on Trial in America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2008), 4–5, 9–11, 70–110.

See generally Donald M. Jacobs, ed., Courage and Conscience: Black and White Abolitionists in Boston (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1993); Manisha Sinha, The Slave’s Cause: A History of Abolitionism (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016), 41–42, 67–72, 454. These anti-slavery activists, however, encountered significant resistance. See Josh S. Cutler, The Boston Gentleman’s Mob: Maria Chapman and the Antislavery Riot of 1835 (Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2021). This history is sometimes forgotten. On the complex association between historical memory in discussions of slavery and antislavery see Margot Minardi, Making Slavery History: Abolitionism and the Politics of Memory in Massachusetts (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2012), and Ana Lucia Araujo, Slavery in the Age of Memory: Engaging the Past (New York, NY: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2020.

Joseph Marr Cronin, Reforming Boston’s Schools, 1930 to the Present: Overcoming Corruption and Racial Segregation (New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008), 5, 25–26; Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863 – 1877 (New York, NY: Harper & Row, 1988), 26; Kazuteru Omori, “Race-Neutral Individualism and Resurgence of the Color Line: Massachusetts Civil Rights Legislation, 1855–1895,” Journal of American Ethnic History 22, no. 1 (2002): 32–58; Janette Thomas Greenwood, “A Community within a Community,” in First Fruits of Freedom: The Migration of Former Slaves and Their Search for Equality in Worcester, Massachusetts, 1862 – 1900 (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2010), 131–173; Tony Hill, “Ethnicity and Education,” Boston Review, July 23, 2014, https://bostonreview.net/us/tony-hill-ethnicity-and-education .

A Legacy of African American Resistance

- Get Started

Learning Lab Collections

- Collections

- Assignments

My Learning Lab:

Forgot my password.

Please provide your account's email address and we will e-mail you instructions to reset your password. For assistance changing the password for a child account, please contact us

You are about to leave Smithsonian Learning Lab.

Your browser is not compatible with site. do you still want to continue.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Slavery in America

By: History.com Editors

Published: April 25, 2024

Millions of enslaved Africans contributed to the establishment of colonies in the Americas and continued laboring in various regions of the Americas after their independence, including the United States. Many consider a significant starting point to slavery in America to be 1619 , when the privateer The White Lion brought 20 enslaved Africans ashore in the British colony of Jamestown , Virginia . The crew had seized the Africans from the Portuguese slave ship São João Bautista. Yet, enslaved Africans had been present in regions such as Florida, that are part of present-day United States nearly one century before.

Throughout the 17th century, European settlers in North America turned to enslaved Africans as a cheaper, more plentiful labor source than Indigenous populations and indentured servants, who were mostly poor Europeans.

Existing estimates establish that Europeans and American slave traders transported nearly 12.5 million enslaved Africans to the Americas. Of this number approximately 10.7 million disembarked alive in the Americas. During the 18th century alone, approximately 6.5 million enslaved persons were transported to the Americas. This forced migration deprived the African continent of some of its healthiest and ablest men and women.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, enslaved Africans worked mainly on the tobacco, rice and indigo plantations of the southern Atlantic coast, from the Chesapeake Bay colonies of Maryland and Virginia south to Georgia.

Slavery in Plantations and Cities

In the 17th and 18th centuries, enslaved Africans worked mainly on the tobacco, rice and indigo plantations of the southern coast, from the Chesapeake Bay colonies of Maryland and Virginia south to Georgia. Starting 1662, the colony of Virginia and then other English colonies established that the legal status of a slave was inherited through the mother. As a result, the children of enslaved women legally became slaves.

Before the rise of the American Revolution , the first debates to abolish slavery emerged. Black and white abolitionists contributed to the enactment of new legislation gradually abolishing slavery in some northern states such as Vermont and Pennsylvania. However, these laws emancipated only the newly born children of enslaved women.

Did you know? One of the first martyrs to the cause of American patriotism was Crispus Attucks, a former enslaved man who was killed by British soldiers during the Boston Massacre of 1770. Some 5,000 Black soldiers and sailors fought on the American side during the Revolutionary War.

But after the end of the American Revolutionary War , slavery was maintained in the new states. The new U.S. Constitution tacitly acknowledged the institution of slavery, when it determined that three out of every five enslaved people were counted when determining a state's total population for the purposes of taxation and representation in Congress.

Throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, European and American slave merchants purchased enslaved Africans who were transported to the Americas and forced into slavery in the American colonies and exploited to work in the production of crops such as tobacco, wheat, indigo, rice, sugar, and cotton. Enslaved men and women also performed work in northern cities such as Boston and New York, and in southern cities such as Charleston, Richmond, and Baltimore.

By the mid-19th century, America’s westward expansion and the abolition movement provoked a great debate over slavery that would tear the nation apart in the bloody Civil War . Though the Union victory freed the nation’s four million enslaved people, the legacy of slavery continued to influence American history, from the Reconstruction to the civil rights movement that emerged a century after emancipation and beyond.

In the late 18th century, the mechanization of the textile industry in England led to a huge demand for American cotton, a southern crop planted and harvested by enslaved people, but whose production was limited by the difficulty of removing the seeds from raw cotton fibers by hand.

But in 1793, a U.S.-born schoolteacher named Eli Whitney invented the cotton gin , a simple mechanized device that efficiently removed the seeds. His device was widely copied, and within a few years, the South transitioned from the large-scale production of tobacco to that of cotton, a switch that reinforced the region’s dependence on enslaved labor.

Slavery was never widespread in the North as it was in the South, but many northern businessmen grew rich on the slave trade and investments in southern plantations. Although gradual abolition emancipated newborns since the late 18th century, slavery was only abolished in New York in 1827, and in Connecticut in 1848.

Though the U.S. Congress outlawed the African slave trade in 1808, the domestic trade flourished, and the enslaved population in the United States nearly tripled over the next 50 years. By 1860 it had reached nearly 4 million, with more than half living in the cotton-producing states of the South.

Living Conditions of Enslaved People

Enslaved people in the antebellum South constituted about one-third of the southern population. Most lived on large plantations or small farms; many enslavers owned fewer than 50 enslaved people.

Landowners sought to make their enslaved completely dependent on them through a system of restrictive codes. They were usually prohibited from learning to read and write, and their behavior and movement were restricted.

Many enslavers raped women they held in slavery, and rewarded obedient behavior with favors, while rebellious enslaved people were brutally punished. A strict hierarchy among the enslaved (from privileged house workers and skilled artisans down to lowly field hands) helped keep them divided and less likely to organize against their enslavers.

Marriages between enslaved men and women had no legal basis, but many did marry and raise large families. Most owners of enslaved workers encouraged this practice, but nonetheless did not usually hesitate to divide families by sale or removal.

Slave Rebellions

Enslaved people organized r ebellions as early as the 18th century. In 1739, enslaved people led the Stono Rebellion in South Carolina, the largest slave rebellion during the colonial era in North America. Other rebellions followed, including the one led by Gabriel Prosser in Richmond in 1800 and by Denmark Vesey in Charleston in 1822. These uprisings were brutally repressed.

The revolt that most terrified enslavers was that led by Nat Turner in Southampton County, Virginia, in August 1831. Turner’s group, which eventually numbered as many 50 Black men, murdered some 55 white people in two days before armed resistance from local white people and the arrival of state militia forces overwhelmed them.

Like with previous rebellions, in the aftermath of the Nat Turner’s Rebellion, slave owners feared similar insurrections and southern states further passed legislation prohibiting the movement and assembly of enslaved people.

Abolitionist Movement

As slavery expanded during the second half of the 18th century, a growing abolitionist movement emerged in the North.

From the 1830s to the 1860s, the movement to abolish slavery in America gained strength, led by formerly enslaved people such as Frederick Douglass and white supporters such as William Lloyd Garrison , founder of the radical newspaper The Liberator .

While many abolitionists based their activism on the belief that slaveholding was a sin, others were more inclined to the non-religious “free-labor” argument, which held that slaveholding was regressive, inefficient and made little economic sense.

Black abolitionists and antislavery northerners led meetings and created newspapers. They also had begun helping enslaved people escape from southern plantations to the North via a loose network of safe houses as early as the 1780s. This practice, known as the Underground Railroad , gained real momentum in the 1830s.

Conductors like Harriet Tubman guided escapees on their journey North, and “ stationmasters ” included such prominent figures as Frederick Douglass, Secretary of State William H. Seward and Pennsylvania congressman Thaddeus Stevens. Although no one knows for sure how many men, women, and children escaped slavery through the Underground Railroad, it was in the thousands ( estimates range from 25,000 to 100,000).

The success of the Underground Railroad helped spread abolitionist feelings in the North. It also undoubtedly increased sectional tensions, convincing pro-slavery southerners of their northern countrymen’s determination to defeat the institution that sustained them.

Missouri Compromise

America’s explosive growth—and its expansion westward in the first half of the 19th century—would provide a larger stage for the growing conflict over slavery in America and its future limitation or expansion.

In 1820, a bitter debate over the federal government’s right to restrict slavery over Missouri’s application for statehood ended in a compromise: Missouri was admitted to the Union as a slave state, Maine as a free state and all western territories north of Missouri’s southern border were to be free soil.

Although the Missouri Compromise was designed to maintain an even balance between slave and free states, it was only temporarily able to help quell the forces of sectionalism.

Kansas-Nebraska Act

In 1850, another tenuous compromise was negotiated to resolve the question of slavery in territories won during the Mexican-American War .

Four years later, however, the Kansas-Nebraska Act opened all new territories to slavery by asserting the rule of popular sovereignty over congressional edict, leading pro- and anti-slavery forces to battle it out—with considerable bloodshed —in the new state of Kansas.

Outrage in the North over the Kansas-Nebraska Act spelled the downfall of the old Whig Party and the birth of a new, all-northern Republican Party . In 1857, the Dred Scott decision by the Supreme Court (involving an enslaved man who sued for his freedom on the grounds that his enslaver had taken him into free territory) effectively repealed the Missouri Compromise by ruling that all territories were open to slavery.

John Brown’s Raid on Harper’s Ferry

In 1859, two years after the Dred Scott decision, an event occurred that would ignite passions nationwide over the issue of slavery.

John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry , Virginia—in which the abolitionist and 22 men, including five Black men and three of Brown’s sons raided and occupied a federal arsenal—resulted in the deaths of 10 people and Brown’s hanging.

The insurrection exposed the growing national rift over slavery: Brown was hailed as a martyred hero by northern abolitionists but was vilified as a mass murderer in the South.

The South would reach the breaking point the following year, when Republican candidate Abraham Lincoln was elected as president. Within three months, seven southern states had seceded to form the Confederate States of America ; four more would follow after the Civil War began.

Though Lincoln’s anti-slavery views were well established, the central Union war aim at first was not to abolish slavery, but to preserve the United States as a nation.

Abolition became a goal only later, due to military necessity, growing anti-slavery sentiment in the North and the self-emancipation of many people who fled enslavement as Union troops swept through the South.

When Did Slavery End?

On September 22, 1862, Lincoln issued a preliminary emancipation proclamation, and on January 1, 1863, he made it official that “slaves within any State, or designated part of a State…in rebellion,…shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.”

By freeing some 3 million enslaved people in the rebel states, the Emancipation Proclamation deprived the Confederacy of the bulk of its labor forces and put international public opinion strongly on the Union side.

Though the Emancipation Proclamation didn’t officially end all slavery in America—that would happen with the passage of the 13th Amendment after the Civil War’s end in 1865—some 186,000 Black soldiers would join the Union Army, and about 38,000 lost their lives.

The Legacy of Slavery

The 13th Amendment, adopted on December 18, 1865, officially abolished slavery, but freed Black peoples’ status in the post-war South remained precarious, and significant challenges awaited during the Reconstruction period.

Previously enslaved men and women received the rights of citizenship and the “equal protection” of the Constitution in the 14th Amendment and the right to vote in the 15th Amendment , but these provisions of the Constitution were often ignored or violated, and it was difficult for Black citizens to gain a foothold in the post-war economy thanks to restrictive Black codes and regressive contractual arrangements such as sharecropping .

Despite seeing an unprecedented degree of Black participation in American political life, Reconstruction was ultimately frustrating for African Americans, and the rebirth of white supremacy —including the rise of racist organizations such as the Ku Klux Klan (KKK)—had triumphed in the South by 1877.

Almost a century later, resistance to the lingering racism and discrimination in America that began during the slavery era led to the civil rights movement of the 1960s, which achieved the greatest political and social gains for Black Americans since Reconstruction.

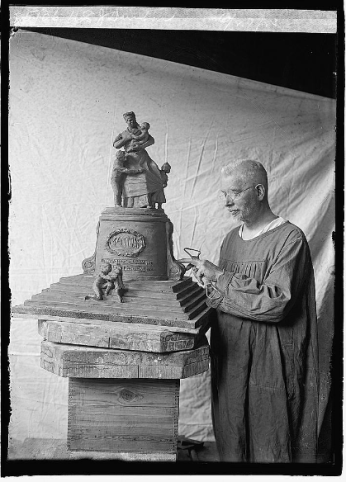

Ana Lucia Araujo , a historian of slavery and the Atlantic slave trade, edited and contributed to this article. Dr. Araujo is currently Professor of History at Howard University in Washington, D.C., and member of the International Scientific Committee of the UNESCO Routes of Enslaved Peoples Projects. Her three more recent books are Reparations for Slavery and the Slave Trade: A Transnational and Comparative History , The Gift: How Objects of Prestige Shaped the Atlantic Slave Trade and Colonialism , and Humans in Shackles: An Atlantic History of Slavery .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Chapter 7 Introductory Essay: 1844-1860

Written by: allen guelzo, princeton university, by the end of this section, you will:.

- Explain the context in which sectional conflict emerged from 1844 to 1877

Introduction

The antebellum period before the Civil War witnessed rapid population and economic growth and several reform movements aimed at improving lives and fulfilling the principles of the American republic. The United States also experienced contention and deep divisions as slavery and the expansion of territory challenged the political balance of power in the nation. The national debate over slavery and its expansion was at the root of the sectional tensions that, despite the efforts of many, led to the Civil War.

Texas, the Mexican War, and Slavery’s Expansion

In the two decades after it was adopted in 1820, the Missouri Compromise promised that virtually all the republic’s future expansion westward would be secured from slavery. In fact, however, the compromise only deflected the energies of westward expansion south-westward to the old Spanish domains, where Mexican revolutionaries (following the American example) had overthrown their colonial overlords and created a Mexican Republic in 1823. Achieving political stability proved more difficult for Mexico than for the United States, and in a bid to promote development, the new Mexican government encouraged American immigrants to settle in the northernmost province of Texas in the 1820s. Mexico soon regretted the decision. American settlers arrived in alarming numbers—some 20,000 by the end of the decade—and showed no inclination to either assimilate themselves to Mexican culture or obey Mexican laws banning slavery. In 1835, these nordamericanos rose in revolt, and after a gallant but bloody defeat at the Alamo in March 1836, they won a resounding victory over Mexican general Antonio López de Santa Anna at San Jacinto on April 21, 1836.

Theodore Gentilz created (a) The Fall of the Alamo in 1844 eight years after the battle in which General Santa Anna gave no quarter. “Remember the Alamo!” became a rallying cry for Texans in their ensuing war for independence. (b) Today what remains of the Alamo is designated as a World Heritage site by the United Nations. (credit b: modification of work by Mary Patterson/Flickr CC BY 4.0)

Texas proclaimed itself an independent republic, which Mexico refused to recognize diplomatically. But Texans’ hopes were on annexation by the United States. President Martin Van Buren ought to have been a friend of annexation: he was the handpicked successor of Andrew Jackson, and Jackson’s Democrats had always been eager to promote westward expansion, especially if it served the interests of southern slaveholders, who filled their ranks. But opposition to westward land grabs and the growth of slavery had already contributed to the creation of the Whig Party, headed by Henry Clay. Besides, Texas had run up substantial debt in its war with Mexico, and the United States, then in the throes of a deep economic recession, was not eager to add to the nation’s bills.

However, in 1844, another Jackson protégé, James Knox Polk of Tennessee, narrowly defeated Henry Clay for the presidency. Polk was dedicated to the ideal of Manifest Destiny and put fresh wind in the sails of expansion. (See the To What Extent Were Manifest Destiny and Westward Expansion Justified? Point-Counterpoint and the Art Analysis: American Progress by John Gast, 1872 Primary Source.) Not only was Texas annexed but Polk agitated for the acquisition of still more Mexican territory in the southwest—New Mexico, California—and demanded border readjustments to the north, along the line dividing Oregon from British Canada. As Democratic journalist John L. O’Sullivan wrote in 1845, it was “our manifest destiny to overspread the continent allotted by Providence for the free development of our yearly multiplying millions.” (See the John O’Sullivan, “Annexation,” 1845 Primary Source.) Polk took this idea to heart, starting with congressional annexation of Texas in 1845. After Mexico protested that it would never recognize the annexation, Polk stationed federal troops at Texas’s southern border. Ten months later, there was a border skirmish, and Polk used it as the pretext for war with Mexico. (See the Debating the Mexican-American War, May 1846 Primary Source and the To Go to War with Mexico? Decision Point.)

U.S. naval and land forces occupied New Mexico and California over only modest opposition. An invasion of northern Mexico by U.S. forces under General Zachary Taylor produced a major victory over a Mexican army commanded by Santa Anna at Buena Vista, and a daring thrust into central Mexico by General Winfield Scott, following the old route of the Spanish conquistadors, succeeded in capturing the capital, Mexico City, on September 13, 1847. The dejected Mexican government signed the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo the following February, conceding the annexation of Texas and surrendering New Mexico and California (including the modern states of Utah, Colorado, Arizona, and Nevada) to the United States. (See The American Southwest: Tucson in Transition Narrative.) Given that most of this Mexican Cession lay below the Missouri Compromise line of 36°30′, the real winners of the war seemed to be southern slaveholders, who now saw a new empire for slavery’s expansion opening at their feet. As one American officer, Ulysses Grant, later wrote in disgust, the war was really nothing but “a conspiracy to acquire territory out of which slave states might be formed for the American Union.”

The U.S. annexation of Texas and the ceding of land by Mexico in the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo added territory south of the Missouri Compromise line. The debate over the future of slavery in the western territories then intensified widening the growing division between North and South.

The Compromise of 1850 and the “Popular Sovereignty” Doctrine

But the destiny of the Mexican Cession was by no means so manifest in Congress. The war with Mexico had hardly begun in the summer of 1846 before a Pennsylvania Representative, David Wilmot, proposed an amendment to an appropriations bill that would require “as an express and fundamental condition to the acquisition of any territory from the Republic of Mexico” that “neither slavery nor involuntary servitude shall ever exist in any part of said territory, except for crime.” The Wilmot Proviso was angrily countered by South Carolina’s pro-slavery senator John C. Calhoun. Calhoun argued that any territory won from Mexico was the “common property” of all the states, and therefore open for slaveholders to migrate to—with their slaves. Yet another proposal came from a northern Democratic senator, Lewis Cass, who urged that the slavery question be “left to the people…in their respective local governments” who would actually settle in the Cession and should have the final say by “popular sovereignty.” President Polk favored a simple extension of the Missouri Compromise line, all the way to the Pacific Ocean. But Polk failed, both in mustering support for such an extension and in reconciling any of the other factions, and he left office in 1848 to be followed by a Whig president, the Mexican War hero Zachary Taylor.

The Missouri Compromise of 1820 resulted in Maine’s being admitted to the Union as a free state and Missouri’s being admitted as a slave state. Slavery was forbidden in the Louisiana Purchase territory above latitude 36°30’ (with the obvious exception of Missouri). Polk’s suggestion to extend the line across the United States’ new territory after the Mexican-American War failed and tensions over slavery’s expansion continued to escalate. (attribution: Copyright Rice University OpenStax under CC BY 4.0 license)

Although Taylor was a southerner and a slaveholder himself, he was convinced that Congress should never “permit a state made from [the Mexican Cession] to enter our Union with the features of slavery connected with it.” The discovery of significant deposits of gold at Sutter’s Mill in California had triggered a massive gold rush and the influx of enough emigrants to justify the direct admission of California without an intervening territorial phase. (See The 49ers Narrative, the Dame Shirley (Mrs. Clappe), Letters from a Western Pioneer, 1851–1852 Primary Source, and the Frank Lecouvreur, From East Prussia to the Golden Gate , 1851–1871 Primary Source.) Taylor used this to push California’s admission as a free state in 1850. Defusing the confrontation in Congress now fell to the master compromiser, Senator Henry Clay, who constructed yet another great national compromise, this time limiting future admissions of states from the Mexican Cession to Senator Cass’s popular sovereignty rule. Clay sweetened the deal for southerners by adding a tough new Fugitive Slave Act, giving federal assistance for the recapture of runaway slaves. (See The Compromise of 1850 Decision Point.)

The real star of the effort behind Clay’s Compromise of 1850 was the Democratic junior senator from Illinois, Stephen A. Douglas, who had engineered the passage of the compromise’s components one by one. As early as 1852, Douglas was already being talked about as a possible Democratic presidential candidate. Although the nomination in that year went instead to the Mexican War veteran Franklin Pierce (who easily defeated the Whig candidate from the Mexican War, Winfield Scott), Douglas was emerging as the most powerful man in the Senate. Moreover, his success in passing the Compromise of 1850 convinced him that popular sovereignty was the key to solving the whole slavery conundrum. Douglas was irritated that slaveholders dissatisfied with the compromise and popular sovereignty were successfully blocking legislation for the organization of the old Louisiana Purchase territories of Kansas and Nebraska, both still governed by the no-slavery agreement of the Missouri Compromise. Brimming with confidence in the idea of popular sovereignty, he introduced legislation in January 1854 that repealed the Missouri Compromise and instead proposed to organize Kansas and Nebraska on the basis of popular sovereignty.

In the words of Illinois lawyer Abraham Lincoln, Douglas’s Kansas-Nebraska Act left many Americans “thunderstruck and stunned; and we reeled and fell in utter confusion.” Northerners in the free states had assumed, a little too readily, that not even popular sovereignty would be enough to promote the use of slaves in the arid wastes of New Mexico, while the protections of the Missouri Compromise would secure the old Louisiana Purchase territories for free labor forever. That assurance was now cruelly ripped away. “But we rose, each fighting,” Lincoln recounted, “grasping whatever he could first reach—a scythe—a pitchfork—a chopping axe, or a butcher’s cleaver”—anything with which to oppose Kansas-Nebraska and the popular sovereignty doctrine. Free Soilers, led by Salmon Chase of Ohio and Charles Sumner of Massachusetts, accused Douglas of advancing a shadowy conspiracy they called “the Slave Power,” which aimed at nothing less than legalizing slavery everywhere in the United States. (See The Free Soil Party Narrative.) The Kansas-Nebraska bill passed anyway, with Democratic president Franklin Pierce supporting it, but the outrage of some Democratic members of Congress remained.

In fact, that anger was stoked by another of Douglas’s creations, the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. This statute put new strength into federal enforcement of the capture and extradition of runaway slaves in the North. In the process, however, it also created sensational showdowns between fugitive slaves and their trackers, sometimes resulting in deadly shootouts, and at other times in disgraceful recaptures of formerly enslaved individuals who had blended peacefully into northern society for years. (See the Fugitive Slave Act, 1850 Primary Source and the Thomas Sims and the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 Narrative.)

This April 24 1851 poster warned blacks about authorities who acted as slave catchers. The Fugitive Slave Act began to turn many northerners into abolitionists.

On May 24, 1854, Anthony Burns who had escaped from slavery to Boston, was apprehended by slave catchers at the store where he worked and had to be marched to a waiting boat in chains, guarded by files of U.S. Marines to prevent his liberation by crowds of angered Bostonians. Amos Lawrence, a pro-Compromise Whig, remembered that after the Burns affair, “We went to bed one night old-fashioned conservative Compromise Union Whigs & waked up stark mad abolitionists.” (See the Henry David Thoreau “Slavery in Massachusetts” 1854 Primary Source.)

Abolitionists and Republicans

Abolitionist was a word few northerners had used to describe themselves before the 1850s; it applied only to a small band of uncompromising opponents of slavery who demanded the immediate and unconditional liberation of all slaves. Their rhetoric was radical. For example, William Lloyd Garrison, an abolitionist leader and editor of the most prominent abolitionist journal, The Liberator , accused the Constitution of complicity with slavery and publicly burned a copy of it with the declaration that it was “a covenant with death, and an agreement with hell.” (See the William Lloyd Garrison and Frederick Douglass on Abolition, 1845–1852 Primary Source.)

The Fugitive Slave Act began to change northerners’ hesitation about abolition, and it changed them still more after June 1851, when the antislavery newspaper National Era began serializing a new novel by Harriet Beecher Stowe entitled Uncle Tom’s Cabin: or, Life Among the Lowly . (See the Harriett Beecher Stowe and Uncle Tom’s Cabin Narrative.) Stowe, who came from a religious and reform-oriented family, not only depicted the operation of the Fugitive Slave Act in the most lurid colors but also dramatized how easily southern blacks could be sold, beaten, raped, and even killed by their masters, with no particular legal consequences. When Uncle Tom’s Cabin was released in book form in 1852, about 3,000 copies were sold on its first day. Together, the Fugitive Slave Act, the Kansas-Nebraska Act, and Uncle Tom’s Cabin made the political gap between the free states of the North and the slave states of the South almost unbridgeable.

(a) The caption below the drawing from Uncle Tom’s Cabin reads “Eliza comes to tell Uncle Tom that he is sold and that she is running away to save her child.” The cruelty of the novel’s white slaveholders and the brutality of the slave dealer Simon Legree shocked readers. (b) Author Harriet Beecher Stowe shown here in 1852 believed she had a moral obligation to mold the nation’s conscience.

The first casualty of this polarization was the Whig Party, which collapsed into quarrelling northern and southern factions, with most of the southern Whigs merging into the Democratic Party. Some northern Whigs blamed their party’s troubles on rising tides of Catholic immigrants from Europe, who seemed willing to trade votes for the “Slave Power” for political favors, and they attached themselves to a short-lived anti-immigrant American Party (or “Know-Nothings,” so called from the party members’ pledge to respond to investigators with “I know nothing”). (See the Nativist Riots and the Know-Nothing Party Narrative.) But the majority of northern Whigs (among them Abraham Lincoln) merged instead with disenchanted antislavery Democrats and abolitionists in a new northern antislavery party, the Republicans. In earlier years, the national constituencies of Whigs and Democrats had helped damp down sectional animosities. Now, the parties were becoming the mouthpieces of the country’s two sections, with each section increasingly behaving as though it saw no alternative but to go its own way.

Other casualties were human. If popular sovereignty was now to determine the future of Kansas and Nebraska as free or slave states, then it was up to antislavery and proslavery emigrants to move there and capture that sovereignty by numbers. As they did so, they inevitably clashed, and the clashes turned bloody. On May 24, 1856, a radical abolitionist named John Brown, with four of his sons and two of his neighbors, hacked five unarmed proslavery Kansans to death along Pottawatomie Creek before going underground to escape the law. (See the Kansas-Nebraska Act and Bleeding Kansas Narrative.)

Other events in the mid-1850s contributed to growing sectional tensions. In the fall of 1854, three of President Pierce’s diplomats—James Buchanan, Pierre Soule, and James Mason—formulated the Ostend Manifesto, describing how the United States could extend its expansionist arms into the Caribbean and annex Cuba as a new slave state. At almost the same time, John Brown launched his raid at Pottawatomie Creek, a southern member of Congress, Preston Brooks, accosted Republican leader and abolitionist Charles Sumner on the floor of the Senate and beat him senseless with a cane. (See the Charles Sumner and Preston Brooks Narrative.) On March 6, 1857, the Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, Roger Brooke Taney, a southerner backed by a southern majority of justices, issued a decision in the case of Dred Scott v. Sandford . Dred Scott was an enslaved person living in Missouri who was suing for his freedom because he had lived on free soil for a time. Taney’s decision declared the Missouri Compromise unconstitutional because Congress could not regulate slavery in the territories. It struck down even the requirement that there must be some expression of popular sovereignty before a territory could decide about slavery. Now, in effect, no territory could ban slavery. The Court’s decision also asserted that African Americans were not and could not become citizens of the United States. Taney believed the decision would calm sectional divisions over slavery, but, in fact, it inflamed them. (See the Dred Scott v. Sandford DBQ Lesson.)

Watch this BRI Homework Help video: Dred Scott v. Sandford for more information on the pivotal Dred Scott decision.

Each of these steps only convinced northerners that ever-stronger antislavery steps needed to be taken, if not to abolish slavery (as the abolitionists wanted) then at least to contain its spread. Northerners did not lack for means. In 1858, Abraham Lincoln challenged Stephen A. Douglas for his seat in the U.S. Senate, and although Douglas enjoyed the advantage of public recognition, Lincoln quickly closed that gap by pressing relentlessly on the flaws in Douglas’s popular sovereignty doctrine.

For instance, when was a territory to schedule the vote on legalizing slavery by which its residents’ popular sovereignty would be recorded? Halfway through the process of statehood? What would keep slaveholders from stuffing the territory—and the ballot-boxes—with proslavery votes? If the vote went against legalization, how could the slaveholders in that territory be legally evicted? Above all, how could a mere vote take away from an enslaved human being the natural rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness that the Declaration of Independence had declared were inalienable? “As I would not be a slave, so I would not be a master,” Lincoln wrote on August 1, 1858, in a note for the debates. “This expresses my idea of democracy. Whatever differs from this, to the extent of the difference, is no democracy.” Although Lincoln lost the election because of the state’s system of voting apportionment, the seven open-air debates he held with Douglas deeply damaged Douglas’s career as a national political leader and brought Lincoln national attention. (See the Lincoln-Douglass Debates, 1858 Primary Source.)

In 1858 (a) Abraham Lincoln debated (b) Stephen Douglas seven times in the Illinois race for the U.S. Senate. Although Douglas won the seat the debates propelled Lincoln into the national political spotlight.

Other northerners were growing more impatient. In October 1859, John Brown and a small band of abolitionist recruits stormed the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, hoping to seize the weapons stored there and spark a slave uprising in the western Virginia mountains. The raid was badly bungled, and Brown and his supporters were either killed or hanged for treason. But across the North, a man who in earlier years would have been scorned as a madman was now hailed as a martyr. “He is a man to make friends wherever on earth courage and integrity are esteemed,” said the poet Ralph Waldo Emerson in a tribute to Brown, “the rarest of heroes, a pure idealist, with no by-ends of his own.” (See the John Brown: Hero or Villain? DBQ Lesson and the John Brown and Harpers Ferry Narrative.)

John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry was a radical abolitionist’s attempt to start a revolt that would ultimately end slavery. This 1859 illustration is captioned “Harper’s Ferry insurrection—Interior of the Engine House just before the gate is broken down by the storming party—Col. Washington and his associates as captives held by Brown as hostages.” It is from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Magazine. Do you think it represents a southern or northern version of the raid?

The most telling changes were also the most subtle ones. The South might possess the most valuable export commodity in the world, in the form of cotton, but in every other respect, its economic organization was feeble. Despite a major economic downturn in 1857 and 1858, which hurt the North far more than the South, the free states had 1,125 banks in operation, whereas the slave South had only 297; the North had built 18,123 miles of railroads, whereas the South had only 6,630. The public budgets of the slave states amounted to only a quarter of those of the free states. Above all, the population of the northern states had been gradually outpacing the South’s for decades. In 1840, the population of the free states stood at 9.6 million, and the slave states’ free population at 4.8 million. By 1850, however, the North experienced a dramatic increase of population, fueled largely by immigration from Ireland and Germany, which were experiencing severe famine and political unrest. (See the Irish and German Immigration DBQ Lesson.) The free-state population had grown to 13.4 million, while in the slave states, the free population had increased only to 6.4 million. If antislavery northerners could unite behind a reasonable antislavery candidate for the presidency, they would be able to elect such a candidate purely on the strength of the northern states’ electoral votes, and thus they could finally check the path of southern belligerence.

The North found such a candidate in Abraham Lincoln, who won the Republican presidential nomination in May 1860. (See The Election of 1860 Narrative.) Lincoln was not an abolitionist. He believed the states had the responsibility for ending slavery and promised the South that as president he would have no authority over slavery. He favored emancipation, but only on a gradual timetable and with some form of national legislation and compensation for slaveholders, and he always insisted that he wanted to curtail slavery’s expansion into the territories more than anything else.

All that southerners heard, however, was that Lincoln opposed slavery, and then they handicapped themselves by refusing to endorse the Democratic Party’s favorite, Stephen Douglas. No longer content with Douglas’s popular sovereignty, southern Democrats wanted national slavery legislation and the acquisition of new foreign territory for expanding slavery’s domain, and they split the Democratic Party by nominating a southern proslavery candidate, John C. Breckinridge. Former southern Whigs who wanted to avoid the slavery issue and avert secession organized the Constitutional Union Party and nominated John Bell from Tennessee. With Democrats thus divided between Douglas and Breckinridge and southerners divided between Democrats and the Constitutional Union Party, Lincoln coasted to an easy victory on November 6, 1860. Although he actually won only 39.8 percent of the popular vote (1,865,000 votes), he garnered almost all those votes in northern states with large populations and, therefore, won a lopsided Electoral College majority of 180 of 303 votes.

Southerners understood that this election signaled they had lost control of the political process. On November 12, the South Carolina state legislature called for a state convention to authorize secession from the United States, which it did on December 20. (See the South Carolina Secession Debate, 1860 Lesson.) By February 1, 1861, Georgia, Florida, Mississippi, Alabama, Louisiana, and Texas had quickly followed. Last-minute compromise efforts were made in Congress, first by Kentucky’s senior senator, John J. Crittenden, whom many saw as the heir of Henry Clay in working out compromises, and then by a Peace Convention that met in Washington in February. But the secessionists, who had organized themselves into a new Confederate States of America, were interested not in compromise but in taking possession of federal property within their boundaries, including the military installations at Ft. Pickens in Florida and Ft. Sumter in South Carolina. President-elect Lincoln refused to sanction the compromises in any case. The nation was about to tip over into the abyss of civil war. (See The Election of Lincoln and the Secession of Southern States DBQ Lesson.)

The antebellum period gave rise to reform movements meant to improve lives and fulfill the principles of the American republic. Despite several attempts to compromise sectional tensions led the nation to the brink of civil war in 1860.

Additional Chapter Resources

- Harriet Tubman and the Underground Railroad Narrative

- Commodore Perry and the Opening of Japan Narrative

- Migration West Decision Point

- The Oregon Question: 54-40 or Fight? Decision Point

- Frederick Douglass Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass 1845 Primary Source

- Negro Spirituals Primary Source

- Daniel Webster “7th of March ” 1850 Primary Source

- Sojourner Truth “Ain’t I a Woman?” 1851 Primary Source

- Walt Whitman Leaves of Grass 1855 Primary Source

- Art Analysis: Hudson River School Landscape Paintings 1836-1868 Primary Source

Review Questions

1. The phrase “manifest destiny” was used by journalist John O’Sullivan in 1845 to justify what policy?

- The Louisiana Purchase

- The annexation of territory belonging to Mexico

- The acquisition of the Hawaiian Islands

- War with Great Britain

2. Stephen A. Douglas’s doctrine of popular sovereignty allowed

- slaves to be brought into the free states

- federal marshals to act as deputies in arresting fugitive slaves

- California to be admitted as a free state

- settlers in the territories to decide on the legalization of slavery for themselves

3. Abraham Lincoln’s criticism of popular sovereignty was based on

- his unwillingness to believe a single vote could deprive anyone of the natural right to liberty

- his reading of Uncle Tom’s Cabin

- his personal experience of owning slaves years before

- his participation in the attempt to rescue Anthony Burns

4. Which factor contributed to Abraham Lincoln’s election as president in 1860?

- Lincoln’s popular support came from northern states with many Electoral College votes.

- The Democratic Party had lost support in the South after the Dred Scott case.

- Northern Democrats threw their support behind Lincoln and considered him a moderate.

- A third party the Constitutional Union Party pulled away key Democratic votes.

5. In 1836 many Texans favored annexation by the United States because of

- Mexican military victories at the Alamo and San Jacinto

- President Jackson’s proslavery support

- discontent with Mexico’s policy governing its northern territory

- Whig interest in southern and western territorial expansion

6. A result of the Texas Revolution of 1836 was

- the establishment of an independent Republic of Texas

- the creation of multiple slave states Mexico’s northern territory

- Texas’ ultimate return to the control of the Mexican government

- the immediate annexation of Texas by the United States

7. James K. Polk’s defeat of Henry Clay in the 1844 presidential election led to

- loss of U.S. territorial interests in Oregon

- decreasing public support for westward expansion

- a period of comparative calm in U.S. foreign policy

- a greater likelihood that Texas would be annexed

8. The group with the most to gain from the provisions of the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo was

- New England Whigs

- proslavery southerners

- moderate Republicans

- northern manufacturers

9. Opposition to the Wilmot Proviso came mainly from

- moderate Democrats

- the Whig Party

- the Republican Party

10. Which event hastened statehood for a portion of the Mexican Cession?

- The election of Abraham Lincoln to the presidency

- The passage of the Wilmot Proviso

- The California gold rush

- The U.S. military victory at San Jacinto

11. Provisions of the Compromise of 1850 included

- a tough new fugitive slave act

- continuation of the Missouri Compromise regarding fugitive slaves

- modification of the federal fugitive slave laws to allow extradition of slaves who had escaped to Canada

- abolition of slavery in Washington DC

12. Allowing popular sovereignty in the lands ceded by Mexico in 1848 would have most severely threatened the political balance in the

- House of Representatives

- Supreme Court

- presidential Cabinet

13. In the 1840s and 1850s the existence of the Missouri Compromise line at 36°30′ led to

- strong Northeastern support for the Mexican-American War

- reluctance of southerners in Congress to organize territories north of the line

- relaxation of slave laws in the cotton-rich South

- expansion of cotton cultivation north of the Mason-Dixon line

14. As the 1860 presidential election approached the Southern slave states held an advantage over the North in

- total free population

- number of banking institutions

- value of export commodity

- miles of railroad track

15. Which was a result of passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act?

- Diminished national support for the abolitionist movement

- Legal challenges that led the Act to be declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court

- Reduction of the threat Southern slaveholders perceived from northern interests

- Partisan realignment in the North and the creation of the Republican Party

16. In the 1860 election southern Democrats rejected the presidential candidacy of Stephen Douglas because

- they felt popular sovereignty insufficiently protected their interests

- Abraham Lincoln had considered making Stephen Douglas his vice president

- they knew the slave states held a majority of electoral votes

- South Carolina had already seceded from the Union

17. The U.S. Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision in 1857 marked

- a continuation of Supreme Court’s challenges to the institution of slavery in the 1850s

- an attempt by the Supreme Court to resolve the issue of slavery that Congress had sought to reconcile through compromise

- a reversal of decades of judicial activism by the Supreme Court

- the catalyst that led to the creation of the Republican Party

Free Response Questions

- Describe the solutions proposed for dealing with slavery and its future in the Mexican Cession.

- Explain why the Kansas-Nebraska Act aroused such furious opposition.

- Explain why white southerners in the 1850s considered themselves increasingly isolated politically.

AP Practice Questions

A map published in the Newark Daily Advertiser in 1845.

1. The provided map was created in response to debates surrounding the

- annexation of Texas

- end of the Mexican-American War

- passage of the Fugitive Slave Act

- repeal of the Missouri Compromise

2. Which group would most likely support the argument raised in the provided map?

- Northern Whigs

- Cotton-growing southerners

- Supporters of the Dred Scott decision

3. The sentiments expressed in the provided map most directly reflected a growing belief that

- sectional compromise was both possible and probable

- the New England states represented a formidable opponent in the Senate

- southern slave power was gaining in political strength

- immigrants from Germany and Ireland would sway the vote

Population of the United States 1830-1860

| Total Population | 12 860 702 | 17 63 353 | 23 191 876 | 31 443 321 |

| % Change over decade | 33.5 | 32.7 | 35.9 | 35.6 |

| Total no. of states | 24 | 26 | 30 | 33 |

Immigration to the United States 1820-1859

| Years | 1820-1829 | 1830-1839 | 1840-1849 | 1850-1859 |

| Total Immigration | 99 272 | 422 771 | 1 369 259 | 2 619 680 |

| From Ireland | 51 617 | 170 672 | 656 145 | 1 209 486 |

| From Germany | 5753 | 124 726 | 385 434 | 976 072 |

4. Which population trend for the period 1830-1860 is seen in the two provided tables?

- Population more than doubled over this period.

- The highest rate of increase occurred in the 1830s.

- Immigration primarily accounted for increase in population.

- Each new state brought in two million additional people.

5. A direct result of the immigration trend demonstrated in the provided tables was

- a decline in urban population along the East Coast

- an end to the importation of slaves

- increasing resentment toward immigrants

- an increase in the number of two-income households

6. Which of the following caused the demographic trends from Ireland and Germany (refer to the provided table)?

- War with Mexico

- Sectionalism and the rise of a third party

- Famine and political upheaval

Primary Sources

The American Almanac and Repository of Useful Knowledge for the Year 1859 . Boston: Crosby Nichols & Co. 1859.

Cass Lewis. “Cass Lewis to A.P.O. Nicholson (December 24, 1847).” The American Debate Over Slavery 1760-1865: An Anthology of Sources . Edited by H.L. Lubert K.R. Hardwick S.J. Hammond 200-204. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Co. 2016.

Cong. Globe 29th Cong. 1st Sess. 1214 (August 8, 1846).

Cong. Globe 29th Cong. 1st Sess. 77 (August 12, 1846). https://memory.loc.gov/ll/llcg/016/1200/12651217.tif

Emerson Ralph Waldo. “Speech at Boston November 18, 1859.” Essays First and Second Series English Traits Representative Men Addresses . Edited by Arthur Brisbane. New York: Hearst’s International Library 1914. http://www.bartleby.com/90/1110.html

“The Fugitive Slave Law of 1850.” 31st Congress (1850). A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation. Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/law/help/statutes-at-large/33rd-congress/session-1/c33s1ch59.pdf

Garrison William Lloyd. “Resistance to Tyranny.” Documents of Upheaval: Selections from William Lloyd Garrison’s The Liberator 1831-1865 . Edited by Truman Nelson. New York: Hill & Wang 1866.

Grant Ulysses S. “Personal Memoirs.” Memoirs and Selected Letters . Edited by M.D. McFeely and W.S. McFeely. New York: Library of America 1990.

The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854. 33rd Congress (1854). A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation . Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/law/help/statutes-at-large/33rd-congress/session-1/c33s1ch59.pdf

Lincoln Abraham. Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln . Edited by R.P. Basler. New Brunswick NJ: Rutgers University Press 1953.

Lincoln Abraham. Peoria Speech October 16, 1854. National Park Service. https://www.nps.gov/liho/learn/historyculture/peoriaspeech.htm

Lincoln Abraham. Seventh Debate Alton Illinois. October 15, 1858.- National Park Service. https://www.nps.gov/liho/learn/historyculture/debate7.htm

Lincoln Abraham. Cooper Union Address. February 27, 1860. https://www.nps.gov/liho/learn/historyculture/cooperunionaddress.htm

O’Sullivan John L. “Annexation.” United States Magazine and Democratic Review . July-August 1845;17:5. http://ebooks.library.cornell.edu/cgi/t/text/pageviewer-idx?c=usde;cc=usde;rgn=full%20text;idno=usde0017-1;didno=usde0017-1;view=image;seq=0013;node=usde0017-1%3A3