Library electronic resources outage May 29th and 30th

Between 9:00 PM EST on Saturday, May 29th and 9:00 PM EST on Sunday, May 30th users will not be able to access resources through the Law Library’s Catalog, the Law Library’s Database List, the Law Library’s Frequently Used Databases List, or the Law Library’s Research Guides. Users can still access databases that require an individual user account (ex. Westlaw, LexisNexis, and Bloomberg Law), or databases listed on the Main Library’s A-Z Database List.

- Georgetown Law Library

Constitutional Law and History Research Guide

- Introduction/Key Resources

- Historical Documents & Resources

- Primary Law

- Treatises and Other Secondary Sources

- State Constitutional Law

Key to Icons

- Georgetown only

- On Bloomberg

- More Info (hover)

- Preeminent Treatise

Introduction

This guide provides an introduction to resources for conducting constitutional law research. The U.S. Constitution is widely considered the world's oldest constitutional document still in force today. The broad topic of “constitutional law” deals with the interpretation and implementation of the United States Constitution and covers a wide variety of areas, from the body of law that regulates the federal, state, and local governments of the United States to the fundamental rights of the individual in relation to both federal and state government.

It is important to remember that conducting research on constitutional law, as with many other areas of the law, is not so much an endeavor in finding answers as it is discovering different approaches and learning the sources that guide constitutional interpretation.

Given the breadth and diversity of this topic, we typically recommend that you start your research with secondary sources such as treatises or legal encyclopedias to help you more quickly identify the focus of your research. This research guide includes information on finding historical documents and resources for U.S. Constitutional history research , primary sources , secondary sources for U.S. Constitutional law , and material on state constitutional law research .

As the U.S. Supreme Court plays an integral role in interpreting the Constitution, the study of this area also focuses heavily on the Supreme Court justices and the Court’s rulings. For more information on primary and secondary materials relating to the Supreme Court, consult the Supreme Court Research Guide .

Getting Started: Key Resources

- Encyclopedia of the American Constitution (Levy et al., 2nd ed.) This six-volume work contains essays by leading constitutional scholars, law school professors, judges, historians, and political scientists on practical and theoretical topics dealing with every aspect of constitutional law in the U.S., from the Constitutional Convention in 1787 to the Clinton impeachment.

- Historical Dictionary of the U.S. Constitution (2016) The Historical Dictionary of the U.S. Constitution covers the Founding of the American Republic and the Framers, the drafting of the Constitution, constitutional debates over ratification, and traces key events, Supreme Court chief justices, amendments, and Supreme Court cases regarding the interpretation of the Constitution from 1789-2016.

- Lexis: Constitutional Law Select your area of focus to research, be it Secondary Sources, Statutes or Administrative Material.

- Oxford Constitutional Law: US Constitutional Law US Constitutional Law provides a comprehensive research resource on the law, politics, and history of constitutionalism in the United States at the federal and state levels. Combining extensive primary materials with expert commentary, the service provides researchers with unparalleled access to the historical development of federal and state constitutionalism.

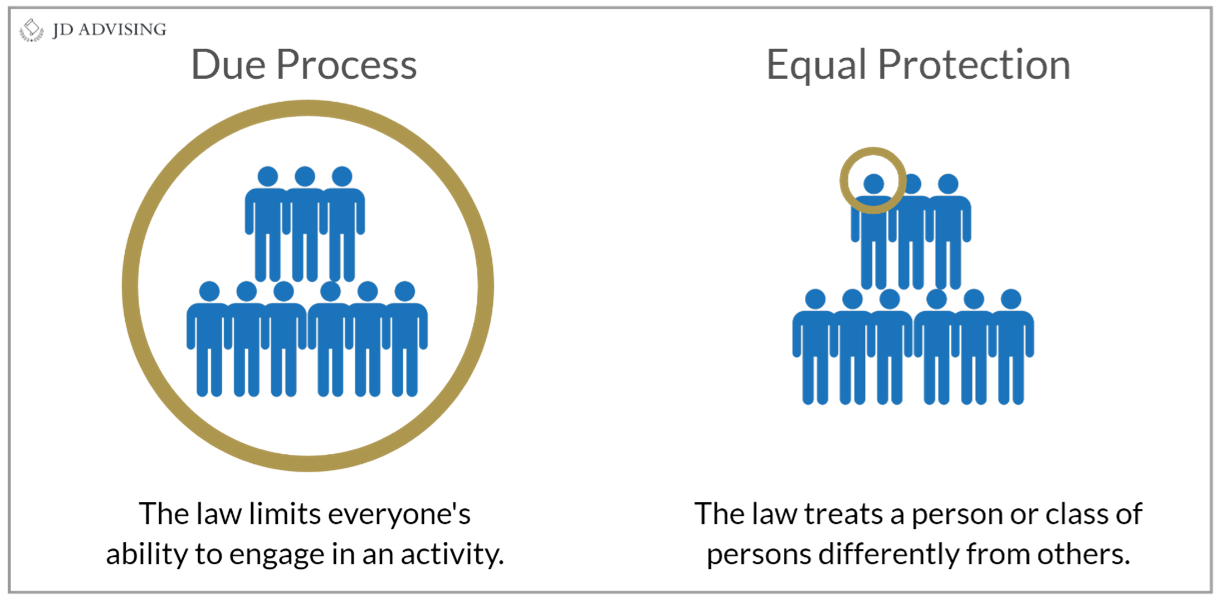

- Rotunda and Nowak's Treatise on Constitutional Law Legal treatise providing up-to-date analysis of every area of federal constitutional law. Focus is primarily on the Supreme Court. Coverage includes: origins of judicial review; sources of national authority; federal fiscal powers; procedural due process; and equal protection.

- Westlaw: Constitutional Law Texts & Treatises A collection of Constitutional Law treatises available on Westlaw. Contains titles pertaining to these areas and more: Anti-SLAPP Litigation, Education Law, Religious Organizations, Search And Seizure, and Freedom of Speech.

Law Library Reference

Reference Desk : Atrium, 2nd (Main) Floor (202) 662-9140 Request a Research Consultation

Additional research resources.

- Supreme Court Research Guide

- American Legal History Guide

- American History Research Guide (Georgetown)

- Constitutional Law Treatises

- Framing of the U.S. Constitution (Library of Congress)

Update History

04/10 (RR) 7/21 (JKK) Updated 5/22 (MK)

- Next: Historical Documents & Resources >>

- © Georgetown University Law Library. These guides may be used for educational purposes, as long as proper credit is given. These guides may not be sold. Any comments, suggestions, or requests to republish or adapt a guide should be submitted using the Research Guides Comments form . Proper credit includes the statement: Written by, or adapted from, Georgetown Law Library (current as of .....).

- Last Updated: Sep 13, 2024 2:04 PM

- URL: https://guides.ll.georgetown.edu/constitutionallaw

- Library of Congress

- Research Guides

- Multiple Research Centers

Constitution Annotated: A Research Guide

Guide to constitution annotated essays.

- Introduction

- How to Use the Constitution Annotated Website

- Resources for Constitution Annotated Research

- Primary and Secondary Sources

- Related Research Guides

As a starting point to your constitutional research, you can begin to explore the Constitution Annotated by subject matter using the menu below or by inputting keywords in the search bar .

The links in the section below take you to the browse section for each constitutional provision's annotated essays. Individual essays can be accessed by clicking the serial numbers left of each essay title.

Introductory Essays

- U.S. Constitution (Articles 1-7)

- Bill of Rights (1-10)

- Early Amendments (11-12)

- Reconstruction Amendments (13-15)

- Early 20th Century Amendments (16-22)

- Post-War Amendments (23-27)

Unratified Amendments

These essays introduce the reader to various components underpinning the Constitution Annotated and how the Constitution is interpreted today.

- Constitution Annotated Methodology This section of essays explains the methodology for the current edition of the Constitution Annotated—that is, the rules and principles that dictate the organization and construction of the document.

- Organization of the Constitution Annotated The section of essays covers how the Constitution Annotated is organized.

- Historical Background of the Constitution This section of essays covers the historical background of the creation of the Constitution in 1787, looking at the Articles of Confederation and the Constitutional Convention.

- Basic Principles Underlying the Constitution This section of essays explores the basic principles underlying and permeating the Constitution, such as federalism, separation of powers, and rights.

- Ways to Interpret the Constitution This section of essays explores the various current frameworks by which the Constitution is interpreted by the Supreme Court, such as textualism, pragmatism, and moral reasoning.

The U.S. Constitution

The foundational legal document of the United States of America.

Legislative Power (Article I)

This section encompasses essays on Article I of the Constitution dealing specifically with the Legislative branch, its powers, and functions. A recommended first stop is the annotated essay on the Historical Origin Limits on Federal Power .

Executive Power (Article II)

This section encompasses essays on Article II of the Constitution dealing specifically with the Executive branch, the Presidency, its powers, and functions. A recommended first stop is the annotated essay on the Overview of Article II, Executive Branch .

Judicial Power (Article III)

This section encompasses essays on Article III of the Constitution dealing specifically with the Judicial branch, its powers, and functions. A recommended first stop is the annotated essay on Marbury v. Madison and Judicial Review .

Interstate Relations (Article IV)

This section encompasses essays on Article IV of the Constitution dealing specifically with the relationships between states. A recommended first stop is the annotated essay on the Purpose of Privileges and Immunities Clause.

Amending the Constitution (Article V)

This section encompasses essays on Article V of the Constitution dealing specifically with the creation of constitutional amendments. A recommended first stop is the annotated essay on Congressional Proposals of Amendments .

Supreme Law (Article VI)

This section encompasses essays on Article VI of the Constitution dealing specifically with the establishment of the Constitution as the Supreme Law of the Land. A recommended first stop is the annotated essay on the Overview of the Supremacy Clause.

Ratification (Article VII)

This section encompasses essays on Article VII of the Constitution dealing specifically with the ratification of the Constitution.

Bill of Rights

The first ten amendments to the Constitution.

First Amendment: Fundamental Freedoms

This section encompasses essays on the First Amendment dealing specifically with fundamental freedoms. A recommended first stop is the annotated essay on State Action Doctrine and Free Speech .

Second Amendment

This section encompasses essays on the Second Amendment dealing specifically with the right to bear arms. A recommended first stop is the annotated essay on Early Second Amendment Jurisprudence.

Third Amendment

This section encompasses essays on the Third Amendment dealing specifically with the quartering of soldiers. A recommended first stop is the annotated essay on Government Intrusion .

Fourth Amendment

This section encompasses essays on the Fourth Amendment dealing specifically with searches and seizures. A recommended first stop is the annotated essay on the Amendment’s Historical Background .

Fifth Amendment

This section encompasses essays on the Fifth Amendment dealing specifically with the rights of persons. A recommended first stop is the annotated essay overviewing Due Process .

Sixth Amendment

This section encompasses essays on the Sixth Amendment dealing specifically with rights in criminal prosecutions. A recommended first stop is the annotated essay on Prejudice and the Right to a Speedy Trial.

Seventh Amendment

This section encompasses essays on the Seventh Amendment dealing specifically with civil trial rights. A recommended first stop is the annotated essay overviewing the Seventh Amendment.

Eighth Amendment

This section encompasses essays on the Eighth Amendment dealing specifically with cruel and unusual punishment. A recommended first stop is the annotated essay on the standard of cruel and unusual punishment.

Ninth Amendment

This section encompasses essays on the Ninth Amendment dealing specifically with unenumerated rights. A recommended first stop is the annotated essay on the Amendment’s modern doctrine.

Tenth Amendment

This section encompasses essays on the Tenth Amendment dealing specifically with rights reserved to states and the people. A recommended first stop is the annotated essay on State Sovereignty .

Early Amendments

The two earliest amendments ratified after the Bill of Rights.

Eleventh Amendment

This section encompasses essays on the Eleventh Amendment dealing specifically with suits against states. A recommended first stop is the annotated essay on the Amendment’s historical background.

Twelfth Amendment

This section encompasses essays on the Twelfth Amendment dealing specifically with the election of the President.

Reconstruction Amendments

Also referred to as the Civil War Amendments, the 13th-15th Amendments were passed in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War to enshrine constitutional protections for newly-freed Black Americans.

Thirteenth Amendment

This section encompasses essays on the Thirteenth Amendment dealing specifically with the abolition of slavery. A recommended first stop is the annotated essay on Defining Badges and Incidents of Slavery

Fourteenth Amendment

This section encompasses essays on the Fourteenth Amendment dealing specifically with equal protection and other rights. A recommended first stop is the annotated essay overviewing Substantive Due Process .

Fifteenth Amendment

This section encompasses essays on the Fifteenth Amendment dealing specifically with the right to vote. A recommended first stop is the annotated essay on the right to vote generally .

Early Twentieth Century Amendments

The constitutional amendments ratified in the early twentieth century prior to the Second World War.

Sixteenth Amendment

This section encompasses essays on the Sixteenth Amendment dealing specifically with income tax. A recommended first stop is the annotated essay on the historical background of the Amendment.

Seventeenth Amendment

This section encompasses essays on the Seventeenth Amendment dealing specifically with the popular election of senators. A recommended first stop is the annotated essay on the historical background of the Amendment.

Eighteenth Amendment

This section encompasses essays on the Eighteenth Amendment dealing specifically with the prohibition of alcohol.

Nineteenth Amendment

This section encompasses essays on the Nineteenth Amendment dealing specifically with women’s suffrage. A recommended first stop is the annotated essay overviewing the amendment .

Twentieth Amendment

This section encompasses essays on the Twentieth Amendment dealing specifically with the presidential terms and succession.

Twenty-First Amendment

This section encompasses essays on the Twenty-First Amendment dealing specifically with the repeal of prohibition. A recommended first stop is the annotated essay on interstate commerce .

Twenty-Second Amendment

This section encompasses essays on the Twenty-Second Amendment dealing specifically with Presidential term limits.

Post-War Amendments

Constitutional amendments passed in the twentieth century after the conclusion of the Second World War.

Twenty-Third Amendment

This section encompasses essays on the Twenty-Third Amendment dealing specifically with District of Columbia electors.

Twenty-Fourth Amendment

This section encompasses essays on the Twenty-Fourth Amendment dealing specifically with the abolition of poll tax.

Twenty-Fifth Amendment

This section encompasses essays on the Twenty-Fifth Amendment dealing specifically with Presidential vacancy.

Twenty-Sixth Amendment

This section encompasses essays on the Twenty-Sixth Amendment dealing specifically with the reduction of voting age.

Twenty-Seventh Amendment

This section encompasses essays on the Twenty-Sixth Amendment dealing specifically with the congressional compensation. A recommended first stop is the annotated essay overviewing the amendment .

Six amendments have been proposed by Congress, but have not been ratified by the States.

- Proposed Amendments Not Ratified by the States This essay covers amendments proposed by Congress, but as of yet unratified by the States.

- << Previous: How to Use the Constitution Annotated Website

- Next: Resources for Constitution Annotated Research >>

- Last Updated: Apr 11, 2024 8:12 AM

- URL: https://guides.loc.gov/constitution-annotated

Our systems are now restored following recent technical disruption, and we’re working hard to catch up on publishing. We apologise for the inconvenience caused. Find out more: https://www.cambridge.org/universitypress/about-us/news-and-blogs/cambridge-university-press-publishing-update-following-technical-disruption

We use cookies to distinguish you from other users and to provide you with a better experience on our websites. Close this message to accept cookies or find out how to manage your cookie settings .

Login Alert

- > Journals

- > Global Constitutionalism

- > Volume 1 Issue 2

- > Proportionality and freedom—An essay on method in constitutional...

Article contents

Proportionality and freedom—an essay on method in constitutional law.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 06 June 2012

This article presents a functional explanation of why proportionality has become one of the most successful legal transplants in contemporary constitutional law. It argues that proportionality helps judges mitigate what Robert Cover called the ‘inherent difficulty presented by the violence of the state’s law acting upon the free interpretative process’. More than alternative methods, proportionality calibrates the violence that the justification of state coercion inflicts on private (non-official) jurisgenerative interpretative processes in constitutional cases. The first three sections show, through an analysis of different constitutional styles which I label Doric, Ionic and Corinthian, how proportionality seeks to place a non-deontological conception of rights within a categorical structure of formal legal analysis. This method aims to synthesize fidelity to form and institutional structure (thesis) with ‘fact-sensitivity’ to contexts in which specific controversies arise (antithesis). Proportionality positions judges vis-à-vis the parties and the parties in relation to one another differently from other constitutional methods. The next sections distinguish between constitutional perception and reality. While the normative appeal of proportionality can be traced to the perception of its integrative aims, in reality, judicial technique does not entirely live up to those aims. Proportionality succumbs to pressures from the centrifugal forces of universalism and particularism that it seeks to integrate. The final section draws on the works of Kant and Arendt and discusses the implications of an approach to constitutional method such as that reflected in the advent of proportionality for the project of constitutionalism more generally.

Access options

1 Beatty , David , The Ultimate Rule of Law ( Oxford University Press , Oxford , 2004 ) 162 . CrossRef Google Scholar

2 Kumm , Mattias , ‘ Constitutional Rights as Principles: On the Structure and Domain of Constitutional Justice ’ ( 2003 ) 2 International Journal of Constitutional Law 574 –96, 595. CrossRef Google Scholar

3 Ibid 582. (‘Having a right does not confer much on the rights holder: that is to say, the fact that he or she has a prima facie right does not imply a position that entitles him/her to prevail over countervailing considerations of policy.’)

4 Barak , Aharon , ‘ Proportionality and Principled Balancing ’ ( 2010 ) 4 Law and Ethics of Human Rights 1 – 18 , 14. CrossRef Google Scholar

5 See, e.g. Sweet , Alec Stone and Mathews , Jud , ‘ Proportionality Balancing and Global Constitutionalism ’ ( 2008 ) 47 Columbia Journal of Transnational Law 72 , 160 Google Scholar ; Barak , Aharon , Proportionality: Constitutional Rights and their Limitations ( Cambridge University Press , Cambridge , 2012 ). CrossRef Google Scholar

6 For a study of proportionality in the context of American law generally, see Sullivan , E Thomas and Frase , Richard S , Proportionality Principles in American Law: Controlling Excessive Government Actions ( Oxford University Press , Oxford , 2008 ) CrossRef Google Scholar ; Mathews , Jud and Sweet , Alec Stone , ‘ All Things in Proportion? American Rights Review and the Problem of Balancing ’ ( 2011 ) 60 Emory Law Journal 797 Google Scholar ; Cohen-Eliya , Moshe and Porat , Iddo , ‘ The Hidden Foreign Law Debate in Heller: The Proportionality Approach in American Constitutional Law ’ ( 2009 ) 46 San Diego Law Review 367 . Google Scholar

7 Stone Sweet and Mathews (n 5) 160. The authors base this conclusion on the observation that ‘By the end of the 1990s, virtually every effective system of constitutional justice in the world, with the partial exception of the United States, had embraced the main tenets of proportionality analysis.’ Ibid 74.

8 See, e.g. Cohen-Eliya , Moshe and Porat , Iddo , ‘ Proportionality and the Culture of Justification ’ ( 2011 ) 59 American Journal of Comparative Law 463 –90 CrossRef Google Scholar ; Kumm , Mattias , ‘ The Idea of Socratic Contestation and the Right to Justification: The Point of Rights-Based Proportionality Review ’ ( 2010 ) 4 Law and Ethics of Human Rights 141 –57. CrossRef Google Scholar

9 Cover , Robert , ‘ Foreword: Nomos and Narrative ’ ( 1983 ) 97 Harvard Law Review 4 , 48 Google Scholar . Since the state is often involved as a party in constitutional conflict seeking court permission to override individual rights, Cover’s mention of ‘state law’ is best understood as referring to the ‘law of the state’. My emphasis on interpretation here tracks Cover’s, insofar as it is an emphasis on constitutional (as a form of legal) interpretation. For an argument about law’s ‘homicidal potential’, by contrast—or, perhaps, in relation to—its jurispathic dimension, see Cover , Robert , ‘ Violence and the Word ’ ( 1986 ) 95 Yale Law Journal 1601 . CrossRef Google Scholar

10 The formulation is Rousseau’s. See Rousseau , Jean-Jacques , The Social Contract [1762] ( Penguin , London , 1968 ) Google Scholar Book I, ch 7.

11 ‘Private’ should not be interpreted as ‘individual’ but as ‘non-official’. It includes the government’s constitutional interpretation seeking protection of its state interests.

12 I should note that Cover’s own substantive position about the possibility of justification is far more sceptical than the position presented in this article. For more on this difference, see (n 17).

13 See e.g. Pogge , Thomas , Politics as Usual ( Polity Press , Cambridge , 2010 ) Google Scholar (defining as a feature of democracy ‘the moral imperative that political institutions should maximize and equalize citizens’ability to shape the social context in which they live’.) 200.

14 I discuss the duty of responsiveness in Perju , Vlad , ‘ Cosmopolitanism and Constitutional Self-Government ’ ( 2010 ) 8 International Journal of Constitutional Law 326 –53 CrossRef Google Scholar . For now I should only mention that I don’t understand ‘responsiveness’as a purely procedural value. For such an approach, see the analysis in Michelman , Frank , ‘ Must Constitutional Democracy be ‘‘Responsive’’ ?’ ( 1997 ) 107 Ethics 706 –23 CrossRef Google Scholar (reviewing and analysing the procedural conception of democratic responsiveness in Robert Post’s Constitutional Domains ).

15 For an argument about how constitutional rights become interests by entering the decisional calculus, see Fallon , Richard , ‘ Individual Rights and the Powers of Government ’ ( 1993 ) 27 Georgia Law Review 343 . Google Scholar

16 As Habermas put it, ‘norms of action appear with a binary validity claim and are either valid or invalid; we can respond to normative sentences, as we can to assertoric sentences, only by taking a yes or no position or by withholding judgment’, in Habermas , , Between Facts and Norms ( MIT Press , Cambridge, MA , 1996 ) 255 Google Scholar . See also Dworkin , Ronald , A Matter of Principle ( Harvard University Press , Cambridge, MA , 1985 ) 119 –20 Google Scholar (discussing the bivalence thesis that applies to law, as to all dispositive concepts).

17 There are limits inherent in the process of justification. Robert Cover refers to them as tragic limits in the common meaning that can be achieved in justifying the social organization of legal violence. See Cover , Robert , ‘ Violence and the Word ’ 95 Yale Law Journal ( 1986 ) 1601 , 1628–9. CrossRef Google Scholar

18 Tilly , Charles , Why? ( Princeton University Press , Princeton , 2006 ) 24 –5 Google Scholar (footnotes omitted).

19 Beatty (n 1) 169. Kumm argues that proportionality marks the shift from interpretation to justification: ‘The proportionality test merely provides a structure for the demonstrable justification of an act in terms of reasons that are appropriate in a liberal democracy. Or to put it another way: it provides a structure for the justification of an act in terms of public reason’, in Mattias Kumm (n 8) 150. However, it is important to incorporate in a theory of proportionality the perspective of the right-holder himself. From that perspective, proportionality remains a method of interpretation. As I argue in the third and fourth sections, a virtue of proportionality is that it can integrate both perspectives.

20 For a discussion of available explanations, see Cohen-Eliya and Porat (n 8) 467–74.

21 On functional explanations, see Cohen , GA , Karl Marx’s Theory of History ( Oxford University Press , New York , 1978 ) 249 –77. Google Scholar

22 I borrow this phrase from Dworkin , Ronald , A Bill of Rights for Britain ( Chatto & Windus , London , 1990 ). Google Scholar

23 For a discussion of the different orders of Greek and Roman architecture, see Hearn , Fil , Ideas That Shaped Buildings ( MIT Press , Cambridge, MA , 2003 ) 97 – 133 . Google Scholar

24 Sales , Philip and Hooper , Ben , ‘ Proportionality and the Form of Law ’ ( 2003 ) 119 Law Quarterly Review 426 –54, 428. Google Scholar

25 Arendt , Hannah , ‘Understanding and Politics’ in Kohn , Jerome (ed), Essays in Understanding 1930–1954 ( Harcourt Brace , New York , 1994 ) 323 . Google Scholar

26 Walzer , Michael , Interpretation and Social Criticism ( Harvard University Press , Cambridge, MA , 1987 ) 37 . Google Scholar

27 Koskenniemi , Martti , The Gentle Civilizer of Nations: The Rise and Fall of International Law 1870–1960 ( Cambridge University Press , New York , 2004 ) 503 –4. Google Scholar

28 Fried , Charles , ‘ Two Concepts of Interests: Some Reflections on the Supreme Court’s Balancing Test ’ ( 1963 ) 76 Harvard Law Review 755 , 761. CrossRef Google Scholar

29 ‘Form is the sworn enemy of caprice, the twin sister of liberty … Fixed forms are the school of discipline and order, and thereby of liberty itself. They are the bulwark against external attacks, since they will only break, not bend, and where a people has truly understood the service of freedom, it has also instinctively discovered the value of form and has felt intuitively that in its forms it did not possess and hold to something purely external, but to the palladium of its liberty.’ (Rudolf von Jhering, quoted in Pound , Roscoe , ‘ The End of Law as Developed in Legal Rules and Doctrines ’ ( 1914 ) 27 Harvard Law Review 195 , 208–9. CrossRef Google Scholar

30 Fried (n 28) ibid.

31 There are a number of ways in which the constitutional spaces are carved out, and here I focus on just one approach. See generally Gardbaum , Stephen , ‘ A Democratic Defense of Constitutional Balancing ’ ( 2010 ) 4 Law & Ethics of Human Rights 1 – 28 . CrossRef Google Scholar

32 Pildes , Richard H , ‘ Avoiding Balancing: The Role of Exclusionary Reasons in Constitutional Law ’ ( 1994 ) 45 Hastings Law Journal 711 , 713. Google Scholar

33 This is the idea of exclusionary reasons. See Raz , Joseph , Practical Reason and Norms ( Oxford University Press , Oxford , 1999 ) 35 – 49 CrossRef Google Scholar . See also Waldron , Jeremy , ‘ Pildes on Dworkin’s Theory of Rights ’ ( 2000 ) 29 Journal of Legal Studies 301 CrossRef Google Scholar (‘Rights are limits on the kinds of reasons that the state can appropriately invoke in order to justify its actions.’). See also Pildes (n 32) 712.

34 Howe , , ‘ Foreword: Political Theory and the Nature of Liberty ’ ( 1953 ) 67 Harvard Law Review 91 CrossRef Google Scholar (‘Government must recognize that it is not the sole possessor of sovereignty, and that private groups within the community are entitled to lead their own free lives and exercise within the area of their competence an authority so effective as to justify labeling it a sovereign immunity.’).

35 For this interpretation of the early abortion cases, see Tribe , Laurence , ‘ Structural Due Process ’ ( 1975 ) 10 Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review 269 . Google Scholar

36 District of Columbia v. Heller 554 U.S. 570 (2008).

37 See Abigail Alliance for Better Access to Experimental Drugs v. Eschenbach , 495 F.3d 695 (D.C. Cir. 2007), cert. denied mem., 128 S.Ct. 1069 (2008).

38 The scheme can be ‘the very product of [substantive] interest-balancing’. 128 S. Ct. 2783 at 2821 (Scalia, J)

39 Fried (n 28) 769. The right to free speech is a second-order reason about how the constitution allocates decision-making power within the spheres of authority that it carves out.

40 Walzer , Michael , ‘ Liberalism and the Art of Separation ’ ( 1984 ) 12 Political Theory 315 –30 CrossRef Google Scholar , 315. Walzer continues: ‘The art of separation is not an illusory or fantastic enterprise; it is a morally and politically necessary adaptation to the complexities of modern life. Liberal theory reflects and reinforces a long-term process of social differentiation.’

41 Habermas (n 16) 257.

42 Dworkin , Ronald , Taking Rights Seriously , ( Harvard University Press , Cambridge, MA , 1977 ) 269 . Google Scholar

43 Ibid 277.

44 Waldron , Jeremy , ‘ Rights in Conflict ’, 99 Ethics ( 1989 ) 503 –19, 516. CrossRef Google Scholar

45 Martti Koskenniemi (n 27) 502. (‘To put it simply and, I fear, through a banality it may not deserve, the message is that there must be limits to the exercise of power, that those who are in positions of strength must be accountable and that those who are weak must be heard and protected, and that when professional men and women engage in an argument about what is lawful and what is not, they are engaged in a politics that imagines the possibility of a community overriding particular alliances and preferences and allowing a meaningful distinction between lawful constraint and the application of naked power.’)

46 For a discussion, see generally Stephen Gardbaum, ‘Limiting Constitutional Rights’ (2007) 54 UCLA Law Review 785 (discussing ‘internal limits’ on rights).

47 At the same time, as the example of the American constitutional culture shows, the constant reaffirmation through public discourse of the deontological conception of rights in a Doric culture of liberty can be a successful self-fulfilling prophecy. For a critical discussion of the broader cultural implications of this deontological approach to rights in the US context, see Glendon , Mary-Ann , Rights Talk: The Impoverishment of Political Discourse ( Free Press , New York , 1991 ). Google Scholar

48 Koskenniemi (n 27) 501. (‘Formalism seeks to persuade the protagonists (lawyers, decisionmakers) to take a momentary distance from their preferences and to enter a terrain where these preferences should be justified, instead of taken for granted, by reference to standards that are independent from their particular positions or interests.’)

49 Young , Iris Marion , Justice and the Politics of Difference ( Princeton University Press , Princeton , 1990 ) 100 . Google Scholar

50 Minow , Martha , ‘ Interpreting Rights: An Essay for Robert Cover ’ 96 Yale Law Journal 1860 CrossRef Google Scholar , 1877 (‘legal positivism or objectivity that implies an authoritative basis or foundation beyond current human choices’). See also Minow , Martha and Spelman , Elizabeth , ‘ In Context ’ ( 1990 ) 63 Southern California Law Review 1597 . Google Scholar

51 Harvey , David , Cosmopolitanism and the Geographies of Freedom ( Columbia University Press , New York , 2009 ) 140 . Google Scholar

52 Wells , Catharine , ‘ Situated Decisionmaking ’ 63 Southern California Law Review ( 1990 ) 1727 , 1728 Google Scholar

53 Resnik , Judith , ‘ On the Bias: Feminist Reconsiderations of the Aspirations for Our Judges ’, ( 1988 ) 61 Southern California Law Review 1877 Google Scholar , 1935. The Ionic architectural order itself was associated with the feminine gender. See Hearn (n 23) 110.

54 Catharine Wells (n 52) 1734 (‘Understanding a controversy … requires that it be experienced from several different perspectives as a developing drama that moves towards its own unique resolution.’).

55 See Grimm , Dieter , ‘ Proportionality in Canadian and German Constitutional Jurisprudence ’ ( 2007 ) 57 University of Toronto Law Journal 383 , 391. CrossRef Google Scholar

56 The legal recognition of interests is of course not unidirectional. Some interests do not pre-exist legal norms; they are, rather, a consequence of their creation. The expectation that a benefit-granting statutory scheme will not be discontinued absent change in circumstances may give rise to interests that cannot logically precede the adoption of that scheme. See Goldberg v. Kelly , 397 U.S. 254 (1970).

57 Beatty (n 1) 171. (‘When rights are factored into an analysis organized around the principle of proportionality, they have no special force as trumps. They are just rhetorical flourish.’)

58 Mattias Kumm (n 2) 582. (‘Having a right does not confer much on the rights holder: that is to say, the fact that he or she has a prima facie right does not imply a position that entitles him/her to prevail over countervailing considerations of policy.’)

59 The outcome of balancing can be stated in the form of a legal rule. See Alexy , Robert , A Theory of Constitutional Rights ( Oxford University Press , New York , 2002 ) 56 Google Scholar (‘The result of every correct balancing of constitutional rights can be formulated in terms of a derivative constitutional rights norm in the form of a rule under which the case can be subsumed.’).

60 Currie , David P , The Constitution of the Federal Republic of Germany ( University of Chicago Press , Chicago , 1994 ) 181 . Google Scholar

61 Alexy (n 59) 57. It is of course possible to devise categorical protections within the model of rights as substantive reasons. As Kumm reminds us, certain types of reasons—say, religious reasons for introducing prayer in public schools—are categorically excluded from the comparative weighting of interests in proportionality analysis. See Kumm (n 2) 591.

62 Scalia, J in Heller 128 S. Ct. at 2821.

63 Rights can also alter the time-horizon in which that process unfolds. For instance, rights can be part of the ongoing interaction between the right-holder and social institutions over time. Martha Minow writes: ‘A claimant asserts a right and thereby secures the attention of the community through the procedures the community has designated for hearing such claims. The legal authority responds, and though this response is temporary and of limited scope, it provides the occasion for the next claim. Legal rights, then, should be understood as the language of a continuing process rather than the fixed rules. Rights discourse reaches temporary resting points from which new claims can be made. Rights, in this sense, are not ‘‘trumps’’ but the language we use to try to persuade others to let us win this round.’ See Martha Minow (n 50) 1875–6 (footnotes omitted).

64 Judith Resnik (n 53) 1935. (‘Rather than bemoan ... a switch in roles, feminism teaches us to celebrate such rearrangements, to require judges to let others judge them. Such moments might better enable judges to be empathetic, to adopt the perspective of the other, to enter into the experience of the courtroom unprotected by their special status. Judge as witness can thus be understood as a profound challenge to a stable hierarchy, as a subversive act to be applauded.’).

65 128 S. Ct. 2850 (Breyer, J, dissenting).

66 Contrasting balancing to rule-based categorical reasoning, Kathleen Sullivan has defended balancing on precisely this ground: ‘rules lose vitality unless their reason for existing is reiterated’, in Sullivan , Kathleen , ‘ Post-Liberal Judging: The Roles of Categorization and Balancing ’ ( 1992 ) 63 University of Colorado Law Review 293 , 309 (footnotes omitted). Google Scholar

67 Sales and Hooper (n 24) 428.

68 I use here Alexy’s standard ‘balancing’ formula: ‘[t]he greater the degree of non-satisfaction of, or detriment to, one right or principle, the greater must be the importance of satisfying the other’ (n 59) 102.

69 Disch , Lisa Jane , Hannah Arendt and the Limits of Philosophy ( Cornell University Press , Ithaca , 1994 ) 162 . Google Scholar

70 Arendt , Hannah , Lectures on Kant’s Political Philosophy ( University of Chicago Press , Chicago , 1989 ) 42 . Google Scholar

71 I borrow this classification (absolute, relative, relational spaces) from David Harvey (n 51), although I should point out that my use does not completely track Harvey’s. For more on relational space, see Lefebvre , Henri , The Production of Space ( Blackwell , Oxford , 1991 ). Google Scholar

72 This phrase is Amartya Sen’s. Sen argues for conception of objectivity that is positional-dependent and person-independent. Observations and beliefs are objective if any subject could reproduce them when placed in a position similar to that of the initial observer. The challenge then becomes how to define the position-dependent. See Sen , Amartya , ‘ Positional Objectivity ’ 22 Philosophy and Public Affairs ( 1993 ) 126 –45. Google Scholar

73 See Gardbaum (n 46).

74 Grimm (n 55) 397.

75 The idea is also to avoid the twin risk of what the South African Constitutional Court called the ‘mechanical adherence to a sequential check-list,’ S Manamela, 2000 (3) SA 1 (CC) 20 (cited in Gardbaum (n 46) 841).

76 For an example of such analysis in American constitutional law, see United States v. Virginia , 518 U.S. 515 (1996).

77 See Grimm (n 55) 388. Canadian courts initially tried to impose a higher threshold on the government by asking that the governmental objective be ‘pressing and substantial’ ( Barak , Aharon , ‘ Proportional Effect: The Israeli Experience ’, 57 University of Toronto Law Journal 369 , 371 ( 2007 ) CrossRef Google Scholar concern or ‘sufficiently important to justify overriding a Charter [constitutionally protected] right’. See Barak ibid 371 (quoting Hogg , Peter , Constitutional Law of Canada , ( student edn , Carswell, Toronto , 2005 ) 823 Google Scholar . Over time however, as the other steps in the analysis have become more substantial, even Canadian courts have begun to defer more and more to the legislature. See generally Choudhry , Sujit , ‘ So What Is the Real Legacy of Oakes? ’ ( 2006 ) 34 Supreme Court Law Review (2d) 501 ). Google Scholar

78 Some advocates of proportionality—including judges writing extra-judicially—have argued for a more incisive judicial involvement at this stage. President Barak has expressed doubts about the wisdom of deferring to the legislator. See Aharon Barak ibid 371 (‘Despite the centrality of the object component, no statute in Israel has been annulled merely because of the lack of a proper object [or purpose]. A similar approach exists in German constitutional law … This is regrettable. The object component should be given an independent and central role in examining constitutionality, without linking it solely with the means for realizing it. Indeed, not every object is proper from the constitutional perspective. This is not the expression of a lack of confidence in the legislature; rather it is the expression of the status of human rights.’) (footnotes omitted).

79 See Shavit v. The Chevra Kadisha of Rishon Le Zion , C.A. 6024/97 (1999) (Supreme Court of Israel) at § 9.

80 The assumption, as Dieter Grimm put it, is that: ‘It is rarely the case that a legal measure affects a fundamental right altogether. Usually, only a certain aspect of a right is affected … The same is true for the good in whose interest the right is restricted. Rarely is one measure apt to give full protection to a certain good.’ Grimm (n 55) 396.

81 Bagenstos , Samuel , ‘ Subordination, Stigma, and ‘‘Disability’’ ’ ( 2000 ) 86 Virginia Law Review 397 CrossRef Google Scholar , 406 (arguing that disability rights do not have a ‘core’).

82 In the context of freedom of religion, if judges may break the institutional shell of a right, then they may look for the ‘core’ of the free exercise right in the beating heart of the belief and practice of a religious experience, but this is a notoriously sticky enterprise. ‘It is no more appropriate for judges to determine the ‘‘centrality’’ of religious beliefs before applying a ‘‘compelling interest’’ test in the free exercise field, than it would be for them to determine the ‘‘importance’’ of ideas before applying the ‘‘compelling interest’’ test in the free speech field.’ Employment Division, Dept of Human Resources v. Smith , 485 U.S. 660 (1988). See also Shavit v. The Chevra Kadisha of Rishon Le Zion , C.A. 6024/97 (1999) (Supreme Court of Israel) (Judge Englard) (deciding whether Jewish burial societies, which customarily administered cemeteries throughout the country, had the right to prevent family members from inscribing on the deceased’s tombstone her birth and death dates according to the standard Gregorian calendar as well as the Hebrew calendar).

83 For these reasons, the distinction between core and periphery raises more questions than it answers. See also, Rivers , Julian , ‘ Proportionality and Variable Intensity of Review ’ 65 Cambridge Law Journal 174 – 207 CrossRef Google Scholar , 187 (‘The problem with the ‘‘very essence’’ of a right is that it is almost impossible to define it usefully without reference to competing public interests.’).

84 554 U.S. 570 (2008).

85 To be specific, the constitutional provision in the South African Interim Constitution followed the essentialist paradigm of the German style. The Court’s discussion of its shortcomings can be found in S. v. Makwanyane (1995) (3) SALR 391 (CC), para 132 (‘The difficulty of interpretation arises from the uncertainty as to what the ‘‘essential content’’ of a right is, and how it is to be determined. Should this be determined subjectively from the point of view of the individual affected by the invasion of the right, or objectively, from the point of view of the nature of the right and its place in the constitutional order, or possibly in some other way?’).

86 Robert Cover (n 9).

87 Hobbes , , The Leviathan , Tuck , Richard (ed) ( Cambridge University Press , Cambridge , 1996 ). Google Scholar

88 The Supreme Court delivers final statements of legal validity. The common reference is to Justice Jackson’s statement: ‘We are not final because we are infallible, but we are infallible only because we are final’, Brown v Allen 344 US 443, 540 (1953) (Jackson J, concurring). See Alexander , Larry and Schauer , Frederick , ‘ On Extrajudicial Constitutional Interpretation ’ ( 1997 ) 110 Harvard Law Review 1359 . CrossRef Google Scholar

89 I use the idea of ‘legal imaginary’ by analogy with Charles Taylor’s conception of the social imaginary, in Taylor , Charles , Modern Social Imaginaries ( Duke University Press , Durham, NC , 2007 ) Google Scholar . Taylor defined the social imaginary as ‘a largely unstructured and inarticulate understanding of our whole situation ... an implicit map of the social space’. (25)

90 Williams , Bernard , In the Beginning Was the Deed: Realism and Moralism in Political Argument ( Princeton University Press , Princeton , 2005 ). Google Scholar

91 See Hart , HLA , The Concept of Law ( 2nd edn , Clarendon Press , Oxford , 1994 ), Chapter VII. Google Scholar

92 For a critical discussion, see Solum , Lawrence , ‘ On the Indeterminacy Crisis: Critiquing Critical Dogma ’, ( 1987 ) 54 University of Chicago Law Review 462 – 503 CrossRef Google Scholar . See also Tushnet , Mark , ‘ Essay on Rights ’ ( 1984 ) 62 Texas Law Review 1363 . Google Scholar

93 See Jackson , Vicki , ‘ Being Proportional about Proportionality ’ ( 2004 ) 21 Constitutional Commentary 803 . Google Scholar

94 Nozick , Robert , Anarchy, State and Utopia ( Basic Books , New York , 1974 ) 29 . Google Scholar

95 Beatty (n 1) 169.

96 Stone Sweet and Mathews (n 5) 88, 89. The authors see this feature as part of proportionality’s strategic dimension.

97 Beatty (n 1) 172.

98 Arendt , Hannah , The Human Condition ( University of Chicago Press , Chicago , 1958 ) 7 . Google Scholar

99 See Martha Minow (n 50) 1877.

100 As Hannah Arendt wrote referring to judgment in general, ‘impartiality is obtained by taking the standpoints of others into account: impartiality is not the result of some higher standpoint that would then settle the dispute by being above the melée.’ Hannah Arendt (n 70) 42.

101 Arendt (n 98) 57–8.

102 Arendt (n 70) 105–6.

103 See generally Paulo Barrozo, ‘Law as Moral Imagination: The Great Alliance and the Future of Law’ (unpublished dissertation, Harvard University, 2009) (on file with Harvard Law Library).

104 Arendt (n 70) 43.

105 Scarry , Elaine , ‘The Difficulty of Imagining Other People’ in Nussbaum , Martha For Love of Country? ( Beacon Press , Boston, MA , 2002 ) 98 – 110 . Google Scholar

106 Kant , , Critique of Judgment , § 40 ( JH Bernard translation , Hafner, New York , 1951 ) Google Scholar . This is the edition that Arendt used. On her usage, see Arendt (n 70) 157. For a slightly different translation, see Kant , , Critique of the Power of Judgment ( Guyer , Paul (ed) Cambridge University Press , Cambridge , 2000 ) 175 . CrossRef Google Scholar

107 Emphasis on representation of others in judicial reasoning, in the best understanding of the Doric or any of the other styles, is not meant to replace or supplement political representation. The disreputable history of such an approach is told in Koskenniemi , Martti , ‘ Legal Cosmopolitanism: Tom Franck’s Messianic World ’ ( 2003 ) 35 New York University Journal of International Law and Politics 471 . Google Scholar

108 Elaine Scarry (n 105) 106 (my emphasis).

110 They must do so as part of their duties of citizenship. For the idea of citizens as office-holders, see Rawls , John , Law of Peoples ( Harvard University Press , Cambridge, MA , 2001 ) 135 . Google Scholar

111 See Koskenniemi, (n 27) 501.

112 Frost , Robert , ‘The Road Not Taken’ in Fasano , Thomas (ed) Selected Early Poems ( Coyote Canyon Press , Claremont, CA , 2008 ) 141 . Google Scholar

113 For example, see Judith Resnik (n 53) 1935.

114 Disch (n 69) 161.

115 See Robin West, The Anti-Empathic Turn (2011) < http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers . cfm?abstract_id=1885079>. On empathy generally, see Stueber , Karsten , Rediscovering Empathy ( MIT Press , Cambridge, MA , 2006 ). Google Scholar

116 Kant, Critique of Judgment (n 106) 160.

117 See Disch (n 69) 162 (discussing the risks of shifting ‘(others’) prejudices for the prejudices proper to (one’s) own station’). It can be said, with respect to proportionality analysis, that the division into four distinct steps imposes a ‘mental double-check’ aimed precisely at creating the distance necessary to identify and counter possible prejudice. For a discussion of mental double-checks and the psychology of judging, see Kahan , Dan H , Hoffman , David A and Braman , Donald , ‘ Whose Eyes Are You Going to Believe? Scott v Harris and the Perils of Cognitive Illiberalism ’ ( 2009 ) 122 Harvard Law Review 837 . Google Scholar

118 Judicial decisions, like all acts of state authority, are coercive acts. And ‘any coercive act in a liberal democracy has to be conceivable as a collective judgment of reason about what justice and good policy require.’ See Mattias Kumm (n 8) 157.

119 Nedelsky cited in Salyzyn , Amy , ‘ The Role of Agency in Arendt’s Theory of Judgment: A Principled Approach to Diversity on the Bench ’ ( 2004 ) 3 Journal of Law & Equality 165 , 174. Google Scholar

120 Amy Salyzyn ibid 169. (‘While Arendt seeks to appropriate many of the core concepts of Kant’s theory, she rejects his transcendental universalism and moves away from his formalism to situate judgments in real, particular communities.’)

121 Disch (n 69) 158.

122 Arendt (n 70) 42.

123 Hannah Arendt, ‘Truth and Politics’, cited in Ronald Beiner, ‘Interpretative Essay’, in Arendt (n 70) 107.

124 Disch (n 69) 168.

125 Arendt, ‘On the nature of totalitarianism: An essay in understanding’ (quoted in Lisa Disch (n 69) 157) (‘Only imagination is capable of what we know as ‘‘putting things in their proper distance’’ and which actually means that we should be strong enough to remove those which are too close until we can see and understand them without bias and prejudice, strong enough to bridge the abysses of remoteness until we can see and understand those that are too far away as though they were our own affairs. This removing some things and bridging the abysses to others is part of the interminable dialogue for whose purpose direct experience establishes too immediate and too close a contact and mere knowledge erects an artificial barrier.’)

126 Disch (n 69) 162. Arendt goes on. As she describes it: ‘form an opinion by considering a given issue from different viewpoints, by making present in my mind the standpoints of those who are absent: I represent them. … The more people’s standpoints I have present in my mind while I am pondering a given issue, and the better I can imagine how I would feel and think if I were in their place, the stronger will be my capacity for representative thinking and valid my final conclusions, my opinions.’ Arendt (n 70) ‘Interpretative essay’ 107.

127 Waldron , Jeremy , ‘Kant’s Legal Positivism’ ( 1996 ) 109 Harvard Law Review 1535 Google Scholar , 1540 (‘law must be such that its content and validity can be determined without reproducing the disagreements about rights and justice that it is law’s function to supersede.’)

128 This argument has been made in the related context of the American rejection of the use of foreign law in constitutional interpretation. See Michelman , Frank , ‘Integrity-Anxiety?’ in Ignatieff , Michael (ed), American Exceptionalism and Human Rights ( Princeton University Press , Princeton , 2005 ). Google Scholar

129 For such an argument, see Cohen-Eliya and Porat (n 8) 487–90.

130 Reflecting on the public space of politics, Arendt wrote that ‘Whenever people come together, the world thrusts itself between them, and it is in this in-between space that all human affairs are conducted’ in Arendt , Hannah , ‘Introduction into Politics’ in, Kohn , Jerome (ed) The Promise of Politics ( Schocken , New York , 2005 ) 106 . Google Scholar

This article has been cited by the following publications. This list is generated based on data provided by Crossref .

- Google Scholar

View all Google Scholar citations for this article.

Save article to Kindle

To save this article to your Kindle, first ensure [email protected] is added to your Approved Personal Document E-mail List under your Personal Document Settings on the Manage Your Content and Devices page of your Amazon account. Then enter the ‘name’ part of your Kindle email address below. Find out more about saving to your Kindle .

Note you can select to save to either the @free.kindle.com or @kindle.com variations. ‘@free.kindle.com’ emails are free but can only be saved to your device when it is connected to wi-fi. ‘@kindle.com’ emails can be delivered even when you are not connected to wi-fi, but note that service fees apply.

Find out more about the Kindle Personal Document Service.

- Volume 1, Issue 2

- VLAD PERJU (a1)

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045381712000044

Save article to Dropbox

To save this article to your Dropbox account, please select one or more formats and confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you used this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your Dropbox account. Find out more about saving content to Dropbox .

Save article to Google Drive

To save this article to your Google Drive account, please select one or more formats and confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you used this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your Google Drive account. Find out more about saving content to Google Drive .

Reply to: Submit a response

- No HTML tags allowed - Web page URLs will display as text only - Lines and paragraphs break automatically - Attachments, images or tables are not permitted

Your details

Your email address will be used in order to notify you when your comment has been reviewed by the moderator and in case the author(s) of the article or the moderator need to contact you directly.

You have entered the maximum number of contributors

Conflicting interests.

Please list any fees and grants from, employment by, consultancy for, shared ownership in or any close relationship with, at any time over the preceding 36 months, any organisation whose interests may be affected by the publication of the response. Please also list any non-financial associations or interests (personal, professional, political, institutional, religious or other) that a reasonable reader would want to know about in relation to the submitted work. This pertains to all the authors of the piece, their spouses or partners.

Login to your account

Remember Me

Register for a Free Account

Access sample lessons, a free LSAT PrepTest, and 100 question explanations today!

Password (twice) * password strength indicator

Excellent Essay Example 1 (July 2017 Constitutional Law)

This lesson presents a real, excellent response to the July 2017 MEE Constitutional Law question . First, read the essay, then listen to the analysis below.

Download the essay as a PDF.

Excellent Essay

1. Bank v. State A in federal court

The issue is whether this action is permitted under the 11th amendment.

The 11th Amendment prohibits federal law suits against states. It is based in the premise of state sovereign immunity. There are exceptions to the 11th amendment, for example, when a state waives sovereign immunity or 11th amendment protection or when congress, under its 14th Amendment sec 5 power abrogates the state sovereign immunity in a statute. Otherwise, citizens of the state or of other states are not permitted to sue a state directly for damages.

Here, the bank appears to be suing the state directly, along with the superintendent, seeking damages. There is no indication that the statute provides a waiver of the 11th amendment and there is no congressional statute on point, so there is not congressional abrogation. Therefore, the suit is not permitted under the 11th amendment and the bank cannot maintain the suit against the state itself in federal court.

Furthermore, while state officials can be sued in their individual capacities for damages, and in their official capacities for prospective injunctive relief, even if that relief would require some money from the state treasury, they cannot be sued for money damages or retrospective relief. Therefore, the bank's action for damages, even as against the superintendent will not be permitted in federal court.

2. Bank v. Superintendent in federal court

The main issue is whether against a state official in their official capacity seeking injunctive relief can be maintained in federal court given the 11th amendment.

As mentioned above, despite the 11th amendment, state officials can be used in their individual capacities for damages, and in their official capacities for prospective injunctive relief, even if that relief would require some money from the state treasury. A suit against a state officer for injunctive relief will be maintained if it is seeking prospective relief and the effect on the state officers is incidental.

Here, the bank's action for injunctive relief can be maintained against the superintendent. The superintendent is sued in her official capacity and the bank is seeking to stop (enjoin) the enforcement of the statute. Therefore it can be maintained under an Ex Parte Young theory.

Note that the bank clearly has standing since it has already suffered a concrete and particularized injury (loss of $2 million dollars) that is caused by the statute and would be redressed by a favorable finding (that the statute is unconstitutional). It can likely show that it will continue to lose money from lost business as a result of the statute, which would be redressed by an injunction.

In conclusion, this part of the bank's claim can proceed.

3. Constitutionality of Statute

The main issue is whether the statute violates the dormant commerce clause. The commerce clause grants to congress the right to regulate interstate commerce. While states have a general police power to regulate in the interest of the health, safety and welfare of their citizens, the negative implication of the commerce clause, often called the dormant commerce clause, limits what they can do when it places a burden on interstate commerce. Generally, if a state law discriminates against out-of-staters, or against interstate commerce, it will be struck down unless the state can show it is necessary to protect a substantial state interests (unrelated to protectionism). It is does not discriminate, it will be struck down if it places an undue burden on interstate commerce--in other words, the burden on interstate commerce will be weighed against the interest of the state.

Here, while there is some protectionism motivating the statute (it was passed as a result of heavy lobbying by State A based manufacturer of biometric identification equipment), it does not appear to discriminate against out of state companies. It applies to both in state and out of state companies and to companies doing business only within the state, and to those doing business across states. Therefore, it likely does not discriminate. Therefore it will be subject to the balancing test. Here, the burden on interstate commerce appears to be somewhat substantial. Banks that operate in multiple states including State A, will be forced to choose between updating their systems to have biometric identification, or cease to do that kind of business in the state. That could have a substantial impact on interstate commerce. The fact that the large bank has already made this choice is support of that. On the other hand, the state appears to have a strong interest in protecting its citizens against fraud. Despite the security measures of banks, customers are still being subjected to unauthorized transfers by thieves. To the extent that this is impacting its citizens, State A clearly has a strong interest in protecting them. However, it is not clear that this particular biometric approach is an improvement or will work. Experts disagree about whether it is significantly better and the bank clearly thinks it is not. However, given that the state has a strong interest, it likely will pass the balancing test and be upheld.

There are two exceptions, neither applicable here: the market participant exception and congressional authorization. There is no indication in the facts that either apply here. Furthermore, there is no preemption since congress has not regulated in this area.

Note that the privileges and immunities clause of Art IV does not apply because the bank is not an individual citizen, and because the statute, while possibly motivated by protectionism, does not appear to discriminate against out-of-staters.

Analysis of the Sample Essay

Now we're going to look at a representative good answer provided by the state of New York. And like we did with the analysis above, we'll go prompt by prompt, noting what this answer did well and what it could have done even better. Again, this is a good answer, a really good one, in fact.

First, let's just take a look at the overall structure of the first prompt. Remember that our goal is for every written answer to have four parts and in the same order every time. Conclusion, rule, application conclusion. CRAC. Just following that recipe over and over will really help you rack up points on the MEE.

Remember I said that I want your approach to the MEE to be mechanical and automatic to the point where you're not so much writing an essay as just assembling an answer? That's what I mean.

Now, this essay doesn't exactly do that on prompt 1. It starts with a numbered header, "Bank v. State A in federal court." And that's fine if it's there to help the test taker remember what's what, but it's not going to score any points with the grader. And then the first real sentence here is an issue statement rather than a conclusion.

So, right away, we can tell that this essay is doing IRAC instead of CRAC. You might find that, as you're writing the essay, the IRAC formula is easier to follow because you might have to write out the rule paragraph and the application paragraph before you discover your conclusion. That's perfectly fine. Use your first paragraph to state the issue. But it's a super quick fix to edit that first paragraph once you're done with your essay to transform what you initially wrote as an issue into a conclusion, something with the word "because" in it.

For example, instead of "The issue is whether this action is permitted under the Eleventh Amendment," this test taker could have just said, "This suit against State A cannot be maintained because of," and there's that key word "because," indicating your reasoning, "the Eleventh Amendment." Or even better, "because the Eleventh Amendment gives states immunity against suits for money damages."

And it's always good to go ahead and bold or underline that sentence or sentences just to make it super clear for the grader that right here, you've earned your points. Having said that, I'll give the test taker here some credit for noting correctly in the issue statement that the issue here is about the Eleventh Amendment. That's not something that the prompt itself says, so the test taker probably did pick up some points there.

Now, these next two paragraphs are just fantastic. Truly impressive work. The first one is a superb statement of the applicable rule, which, as we discussed above, is the key to this prompt. The last sentence of the paragraph states the main point, "Citizens of the state or other states are not permitted to sue a state directly for damages," and then enumerates the exceptions before it.

Probably could have done that in the other order, I guess, but really great substance for a rule paragraph. In fact, it even notes the rule of Hans v. Louisiana, that even in-state citizens can't sue states for money damages.

The next paragraph I like as well, because it starts off, as all my favorite application paragraphs do, with the word "Here." That tells the grader that you're about to zero in on the fact pattern and also gives you a mental cue for what to do next.

As we discussed earlier, there's really not much application to do on this prompt. This answer goes a little above and beyond by noting that there's no indication of waiver or a valid federal statute abrogating immunity. Those are two things that aren't in the fact pattern, in other words, but would have mattered if they were.

I don't love the next paragraph, which starts, "Furthermore." It's not exactly wrong. State officials are generally immune from money damages when acting in their official capacities, but it's also not responsive to the prompt, which asked whether the bank can maintain a suit in federal court against State A for damages.

The superintendent is the focus of the next prompt, so all this could have been held for that. I think the test taker probably just got carried away here or else felt nervous about having not written enough. But again, once you're done, you're done. Move on.

And finally, and this is really nitpicky, the final C in CRAC, the second conclusion, should be in its own paragraph. So that last sentence, which starts with "Therefore," which is great, that's how it should start, should also be on its own line.

The second prompt sets up a lot like the first in terms of its structure, so I won't belabor the point too much. Again, we want the first part of our written answer to be a conclusion, that's the first C in our C-R-A-C, and ideally a reason as well, something with a "because" in it. Here, the test taker starts with the issue instead, and that's not bad.

The answer does correctly identify the Eleventh Amendment as a relevant issue, which gives the grader something to work with. But it would be pretty easy to come back, even after writing the rest of the answer, and transform that into a bolded conclusion sentence, like "The bank's suit against the state superintendent can be maintained because the Eleventh Amendment, or the doctrine of Ex parte Young, permits parties to seek injunctive relief against state officials in their official capacity."

The next paragraph states the rule and does a good job of conveying all the substance. One thing just to note here is that it says, "as mentioned above," and refers the grader back up to the first prompt. That's not a bad trick if you're really being asked to repeat a rule. And that does sometimes happen, like if back-to-back prompts ask you about two different parties' liability under the same rule. You wouldn't need to repeat the rule for the second party.

But that can also be a signal that maybe you should reorganize your answers. Here, as we noted a minute ago, the "furthermore" sentence in the first prompt is really unnecessary there and would fit more naturally down here under the second prompt.

After that, we get a great application paragraph. It starts off with "Here" and states the very few relevant facts necessary to justify the application of Ex parte Young, and really that's where the application should stop. I'd just jump straight to the "In conclusion" sentence, which is a nice summary, but this test taker goes on to argue that the bank does, in fact, have standing, and that's fine, I suppose.

The rule and the analysis here is correct, but again, it's not particularly responsive to the prompt, which was really focused on injunctive relief and the state superintendent. So this standing analysis would apply equally to the first prompt or the third. So it just feels kind of tacked on here. Again, maybe the test taker was just feeling a need to say a little more. Still, really strong answer on prompt 2.

Let's move on to prompt 3. Again, we're starting off with an issue statement that could easily be made into a conclusion. And here I'm just making one up based on this test taker's own analysis of the rule: "State A's statute is likely constitutional because it will probably survive the applicable balancing test under the Dormant Commerce Clause."

The rule statement here should be set off in its own paragraph just to make things as easy as possible for the grader, but otherwise this one does a great job introducing the Dormant Commerce Clause and the two major rule categories that it contains.

That last sentence could be a little more precise. It's not really whether the law places an undue burden on interstate commerce, but rather whether the burdens on interstate commerce are clearly excessive compared to the putative local benefits. But that's just a matter of getting the weights right on the balancing test.

This next paragraph, which is really long and should be broken in half, is a great illustration of how to tackle a two-part rule, or a rule and a sub-rule, or alternative rules.

Remember that there are two categories under the Dormant Commerce Clause: one for protectionist statutes and one for those that incidentally burden interstate commerce. This test taker recognizes that; they're both stated in that rule paragraph. And then the test taker proceeds to apply them both, one after the other, with two back-to-back applications and conclusions.

In fact, you can even see that because there are two "here" statements. I'd set those off into two different paragraphs, I think, just to make it super clear. The first one is terrific, a great showing of why the statute isn't protectionist for purposes of the Dormant Commerce Clause. And it wraps up with a "Therefore," actually two of them, which again is great.

The second one is also really, really strong. After two prompts that called for basically no use of the fact pattern, the test taker here has deployed a whole bunch of facts, not, you'll note, the precise figures and dollar amounts, but that's okay.

And the test taker does a really good job of showing both sides, which is crucial when you're applying a balancing test like this one. A nice way to make that easy on the grader is to do as this one does and use phrases like "on the other hand," because that both says and shows that you're applying the rule.

It would have been nice to wrap this up with a good, clear "therefore" statement, like the final C in our CRAC structure, instead of the "however," but the sentence there is pretty strong. It says, "It likely will pass the balancing test and be upheld." It would just be more clear if there were a "therefore" before that.

What comes after that is really more like a flourish. The test taker goes on to explain why neither of the major Dormant Commerce Clause exceptions are available here, and also why the Privileges and Immunities Clause of Article IV isn't applicable either.

I mean, it's almost just showing off at this point. The test taker clearly knows their stuff and this kind of thing certainly wouldn't count against the final points, but I wouldn't expect you to pick up all of that, especially the Privileges and Immunities point.

So, overall, this is a truly superb answer.

Lesson Note

No note. Click here to write note.

Click here to reset

Leave a Reply Cancel

You must be logged in to post a comment. You can get a free account here .

Constitutional Law

Notes, cases, and materials on constitutional law, topic notes.

Past Papers

Back to Subjects | Back to Law

Introduction to public law

Constitutional law

Constitutional conventions

Ministerial responsibility

Royal prerogative

Rule of law and powers

Parliamentary Sovereignty

Implied repeal and constitutional statutes

The judiciary

EU supremacy

Devolution of Northern Ireland

Devolution of Scotland and Wales

Constitutional Reform

Introduction

Jurisdiction and errors of law/fact

Discretion and deference

Ground: illegality

Ground: irrationality

Human rights adjudication

Ground: proportionality

Tribunals and Ombudsmen

Ground: procedural fairness and bias

Legitimate Expectations

Amenability

Judicial review procedure and remedies

Rule of Law and powers

Parliamentary sovereignty

EU Supremacy

Human Rights

Errors of law and fact

Legitimate expectations

Past Papers & Questions

1. ‘[Judicial deference] has two distinct sources. The first is the constitutional principle of the separation of powers. The second is no more than a pragmatic view about the evidential value of certain judgments of the executive, whose force will vary according to the subject matter.’ R (Carlile) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2014] UKSC 60, [22] (Lord Sumption)

Critically discuss the role judicial deference plays in judicial review decisions, and the implications, or even dangers, it might pose.

2. ‘I suggest that the non-enforceability of conventions by the Court[s] is of only marginal importance, at least in nearly all situations. In nearly all cases, the power authoritatively to identify and declare the terms of established constitutional conventions will be enough to attract voluntary compliance from the political actors.’ - W R Lederman ‘The Supreme Court of Canada and Basic Constitutional Amendment An Assessment of Reference Re Amendment of the Constitution of Canada (Nos 1, 2 and 3) (1982) 27 McGill LJ 527, 537-538.

Critically discuss the importance of conventions for the UK constitution.

3. ‘The United Kingdom does not have a constitution to be found entirely in a written document. This does not mean there is an absence of a constitution or constitutional law. On the contrary, the United Kingdom has its own form of constitutional law...’ R (on the application of Miller and Dos Santos) v Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union [2016] EWHC 2768 (Admin) [18]

Critically discuss whether there are now legal arguments in favour of codifying the UK Constitution.

4. ‘[I]t could be said that the British Constitution does not know of any rule of law since no superior law puts limits to what Parliament may legislate.’ Phillips, Jackson and Leopold, Constitutional and Administrative Law (Sweet & Maxwell 2001)

Critically discuss whether this statement remains applicable today.

5. ‘The power of public authorities to change policy is constrained by the legal duty to be fair (and other constraints which the law imposes). A change of policy which would otherwise be legally unexceptionable may be held unfair by reason of prior action, or inaction, by the authority.’ Laws LJ in R (Bhatt Murphy) v Independent Assessor [2008] EWCA Civ 755, [50].

With reference to the quote above, critically evaluate whether the judicial practice of enforcing legitimate expectations can be accurately described as being grounded in the principle of fairness.

6. Constitutional Reform Act 2005, section 1, states ‘This Act does not adversely affect [...] the existing constitutional principle of the rule of law’.

Critically discuss the role of the ‘existing constitutional principle of the rule of law’ in the British constitution and particularly its importance in relation to the constitutional position of the judiciary.

7. Critically evaluate the methods of enforcement and accountability for breaches of constitutional conventions.

8. Critically evaluate the legal significance and utility of the Human Rights Act 1998 within the UK Constitution.

9. Critically discuss the continued relevance of Wednesbury review.

10. Critically discuss whether the UK’s accession to the European Union has triggered a constitutional revolution and resulted in the demise of parliamentary sovereignty.

11. Critically evaluate the notion that the UK constitution is principally enforced, protected and upheld by processes that are distinctly political, rather than legal.

The (fictional) Immigration Centres Act 2016 was recently enacted. It was passed using the Parliament Acts 1911 and 1949 because of strong opposition from the House of Lords to some of the powers it confers on the Home Office.

Under the Immigration Centres Act 2016, new facilities will be opened:

- s. 5 ‘the Secretary of State may (if necessary) change the use of other state owned facilities to use as Detention Centres.’

- s. 6 ‘the UK Border Agency (UKBA) will invite tenders from private companies for any contract to manage any facility designated as a Detention Centre under this Act.’

In addition,

- s. 11 ‘the Secretary of State may extend a person’s detention indefinitely if he believes such an extension to be necessary. The person is free to leave the United Kingdom if they choose.’

In April, the Home Secretary, Ms North, made a public statement that a new Detention Centre would shortly be opened on premises currently used by a publicly owned school for children with special learning needs. Alice, one of the children at the school, has severe learning difficulties and her doctors have warned that changing schools may be seriously detrimental to her wellbeing. Her mother contacted their MP, Mr South, who said ‘there will be a consultation and very likely, this change will not happen.’ Alice’s social worker also assured her on at least three occasions that the closure would not happen and Alice would always be able to go to school there. The plan has gone ahead and an Order has been made to close the school without consultation. Ms North says that the social worker had ‘no right’ to make the assurances she did.

Clive works for the UKBA and has been asked to invite tenders from private companies for the contract to run the Detention Centre. The contract is awarded to ‘Lock and Key’, a company run by a close friend of his wife, who had dinner with them the weekend before the decision was made. ‘Prison People’, another company, is unhappy to have missed out.

Daniil has been held in another Detention Centre for the past 6 months. He cannot return to his home country because of armed conflict which makes him afraid for his life. The Home Secretary, Ms North, however, is persuaded based on intelligence she has received that Daniil is involved with an organised criminal group. She has extended his detention ‘until such a time as he can be charged. We are still gathering the evidence. But he is free to leave the country if he chooses.’

Advise Alice, ‘Prison People’ and Daniil.

Digestible Notes was created with a simple objective: to make learning simple and accessible. We believe that human potential is limitless if you're willing to put in the work.

© 2024 Digestible Notes All Rights Reserved.

Our Socials

Coping With A Court One Disagrees With

31 Pages Posted:

Randy E. Barnett

Georgetown University Law Center

Josh Blackman

South Texas College of Law Houston

Date Written: September 11, 2024