We use cookies to give you the best experience possible. By continuing we’ll assume you’re on board with our cookie policy

- A Research Guide

- Research Paper Topics

120 Music Research Paper Topics

How to choose a topic for music research paper:.

Music Theory Research Paper Topics:

- The influence of harmonic progression on emotional response in music

- Analyzing the use of chromaticism in the compositions of Johann Sebastian Bach

- The role of rhythm and meter in creating musical tension and release

- Examining the development of tonality in Western classical music

- Exploring the impact of cultural and historical context on musical form and structure

- Investigating the use of polyphony in Renaissance choral music

- Analyzing the compositional techniques of minimalist music

- The relationship between melody and harmony in popular music

- Examining the influence of jazz improvisation on contemporary music

- The role of counterpoint in the compositions of Ludwig van Beethoven

- Investigating the use of microtonality in experimental music

- Analyzing the impact of technology on music composition and production

- The influence of musical modes on the development of different musical genres

- Exploring the use of musical symbolism in film scoring

- Investigating the role of music theory in the analysis and interpretation of non-Western music

Music Industry Research Paper Topics:

- The impact of streaming services on music consumption patterns

- The role of social media in promoting and marketing music

- The effects of piracy on the music industry

- The influence of technology on music production and distribution

- The relationship between music and mental health

- The evolution of music genres and their impact on the industry

- The economics of live music events and festivals

- The role of record labels in shaping the music industry

- The impact of globalization on the music industry

- The representation and portrayal of gender in the music industry

- The effects of music streaming platforms on artist revenue

- The role of music education in fostering talent and creativity

- The influence of music videos on audience perception and engagement

- The impact of music streaming on physical album sales

- The role of music in advertising and brand marketing

Music Therapy Research Paper Topics:

- The effectiveness of music therapy in reducing anxiety in cancer patients

- The impact of music therapy on improving cognitive function in individuals with Alzheimer’s disease

- Exploring the use of music therapy in managing chronic pain

- The role of music therapy in promoting emotional well-being in children with autism spectrum disorder

- Music therapy as a complementary treatment for depression: A systematic review

- The effects of music therapy on stress reduction in pregnant women

- Examining the benefits of music therapy in improving communication skills in individuals with developmental disabilities

- The use of music therapy in enhancing motor skills rehabilitation after stroke

- Music therapy interventions for improving sleep quality in patients with insomnia

- Exploring the impact of music therapy on reducing symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

- The role of music therapy in improving social interaction and engagement in individuals with schizophrenia

- Music therapy as a non-pharmacological intervention for managing symptoms of dementia

- The effects of music therapy on pain perception and opioid use in hospitalized patients

- Exploring the use of music therapy in promoting relaxation and reducing anxiety during surgical procedures

- The impact of music therapy on improving quality of life in individuals with Parkinson’s disease

Music Psychology Research Paper Topics:

- The effects of music on mood and emotions

- The role of music in enhancing cognitive abilities

- The impact of music therapy on mental health disorders

- The relationship between music and memory recall

- The influence of music on stress reduction and relaxation

- The psychological effects of different genres of music

- The role of music in promoting social bonding and cohesion

- The effects of music on creativity and problem-solving abilities

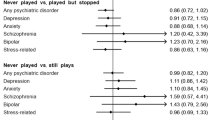

- The psychological benefits of playing a musical instrument

- The impact of music on motivation and productivity

- The psychological effects of music on physical exercise performance

- The role of music in enhancing learning and academic performance

- The influence of music on sleep quality and patterns

- The psychological effects of music on individuals with autism spectrum disorder

- The relationship between music and personality traits

Music Education Research Paper Topics:

- The impact of music education on cognitive development in children

- The effectiveness of incorporating technology in music education

- The role of music education in promoting social and emotional development

- The benefits of music education for students with special needs

- The influence of music education on academic achievement

- The importance of music education in fostering creativity and innovation

- The relationship between music education and language development

- The impact of music education on self-esteem and self-confidence

- The role of music education in promoting cultural diversity and inclusivity

- The effects of music education on students’ overall well-being and mental health

- The significance of music education in developing critical thinking skills

- The role of music education in enhancing students’ teamwork and collaboration abilities

- The impact of music education on students’ motivation and engagement in school

- The effectiveness of different teaching methods in music education

- The relationship between music education and career opportunities in the music industry

Music History Research Paper Topics:

- The influence of African music on the development of jazz in the United States

- The role of women composers in classical music during the 18th century

- The impact of the Beatles on the evolution of popular music in the 1960s

- The cultural significance of hip-hop music in urban communities

- The development of opera in Italy during the Renaissance

- The influence of folk music on the protest movements of the 1960s

- The role of music in religious rituals and ceremonies throughout history

- The evolution of electronic music and its impact on contemporary music production

- The contribution of Latin American musicians to the development of salsa music

- The influence of classical music on film scores in the 20th century

- The role of music in the Civil Rights Movement in the United States

- The development of reggae music in Jamaica and its global impact

- The influence of Mozart’s compositions on the classical music era

- The role of music in the French Revolution and its impact on society

- The evolution of punk rock music and its influence on alternative music genres

Music Sociology Research Paper Topics:

- The impact of music streaming platforms on the music industry

- The role of music in shaping cultural identity

- Gender representation in popular music: A sociological analysis

- The influence of social media on music consumption patterns

- Music festivals as spaces for social interaction and community building

- The relationship between music and political activism

- The effects of globalization on local music scenes

- The role of music in constructing and challenging social norms

- The impact of technology on music production and distribution

- Music and social movements: A comparative study

- The role of music in promoting social change and social justice

- The influence of socioeconomic factors on music taste and preferences

- The role of music in constructing and reinforcing gender stereotypes

- The impact of music education on social and cognitive development

- The relationship between music and mental health: A sociological perspective

Classical Music Research Paper Topics:

- The influence of Ludwig van Beethoven on the development of classical music

- The role of women composers in classical music history

- The impact of Johann Sebastian Bach’s compositions on future generations

- The evolution of opera in the classical period

- The significance of Mozart’s symphonies in the classical era

- The influence of nationalism on classical music during the Romantic period

- The portrayal of emotions in classical music compositions

- The use of musical forms and structures in the works of Franz Joseph Haydn

- The impact of the Industrial Revolution on the production and dissemination of classical music

- The relationship between classical music and dance in the Baroque era

- The role of patronage in the development of classical music

- The influence of folk music on classical composers

- The representation of nature in classical music compositions

- The impact of technological advancements on classical music performance and recording

- The exploration of polyphony in the works of Johann Sebastian Bach

- Writing a Research Paper

- Research Paper Title

- Research Paper Sources

- Research Paper Problem Statement

- Research Paper Thesis Statement

- Hypothesis for a Research Paper

- Research Question

- Research Paper Outline

- Research Paper Summary

- Research Paper Prospectus

- Research Paper Proposal

- Research Paper Format

- Research Paper Styles

- AMA Style Research Paper

- MLA Style Research Paper

- Chicago Style Research Paper

- APA Style Research Paper

- Research Paper Structure

- Research Paper Cover Page

- Research Paper Abstract

- Research Paper Introduction

- Research Paper Body Paragraph

- Research Paper Literature Review

- Research Paper Background

- Research Paper Methods Section

- Research Paper Results Section

- Research Paper Discussion Section

- Research Paper Conclusion

- Research Paper Appendix

- Research Paper Bibliography

- APA Reference Page

- Annotated Bibliography

- Bibliography vs Works Cited vs References Page

- Research Paper Types

- What is Qualitative Research

Receive paper in 3 Hours!

- Choose the number of pages.

- Select your deadline.

- Complete your order.

Number of Pages

550 words (double spaced)

Deadline: 10 days left

By clicking "Log In", you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We'll occasionally send you account related and promo emails.

Sign Up for your FREE account

Explore your training options in 10 minutes Get Started

- Graduate Stories

- Partner Spotlights

- Bootcamp Prep

- Bootcamp Admissions

- University Bootcamps

- Coding Tools

- Software Engineering

- Web Development

- Data Science

- Tech Guides

- Tech Resources

- Career Advice

- Online Learning

- Internships

- Apprenticeships

- Tech Salaries

- Associate Degree

- Bachelor's Degree

- Master's Degree

- University Admissions

- Best Schools

- Certifications

- Bootcamp Financing

- Higher Ed Financing

- Scholarships

- Financial Aid

- Best Coding Bootcamps

- Best Online Bootcamps

- Best Web Design Bootcamps

- Best Data Science Bootcamps

- Best Technology Sales Bootcamps

- Best Data Analytics Bootcamps

- Best Cybersecurity Bootcamps

- Best Digital Marketing Bootcamps

- Los Angeles

- San Francisco

- Browse All Locations

- Digital Marketing

- Machine Learning

- See All Subjects

- Bootcamps 101

- Full-Stack Development

- Career Changes

- View all Career Discussions

- Mobile App Development

- Cybersecurity

- Product Management

- UX/UI Design

- What is a Coding Bootcamp?

- Are Coding Bootcamps Worth It?

- How to Choose a Coding Bootcamp

- Best Online Coding Bootcamps and Courses

- Best Free Bootcamps and Coding Training

- Coding Bootcamp vs. Community College

- Coding Bootcamp vs. Self-Learning

- Bootcamps vs. Certifications: Compared

- What Is a Coding Bootcamp Job Guarantee?

- How to Pay for Coding Bootcamp

- Ultimate Guide to Coding Bootcamp Loans

- Best Coding Bootcamp Scholarships and Grants

- Education Stipends for Coding Bootcamps

- Get Your Coding Bootcamp Sponsored by Your Employer

- GI Bill and Coding Bootcamps

- Tech Intevriews

- Our Enterprise Solution

- Connect With Us

- Publication

- Reskill America

- Partner With Us

- Resource Center

- Bachelor’s Degree

- Master’s Degree

The Top 10 Most Interesting Music Research Topics

Music is a vast and ever-growing field. Because of this, it can be challenging to find excellent music research topics for your essay or thesis. Although there are many examples of music research topics online, not all are appropriate.

This article covers all you need to know about choosing suitable music research paper topics. It also provides a clear distinction between music research questions and topics to help you get started.

Find your bootcamp match

What makes a strong music research topic.

A strong music research topic must be short, straightforward, and easy to grasp. The primary aim of music research is to apply various research methods to provide valuable insights into a particular subject area. Therefore, your topic must also address issues that are relevant to present-day readers.

Also, for your research topic to be compelling, it should not be overly generic. Try to avoid topics that seem to be too broad. A strong research topic is always narrow enough to draw out a comprehensive and relevant research question.

Tips for Choosing a Music Research Topic

- Check with your supervisor. In some cases, your school or supervisor may have specific requirements for your research. For example, some music programs may favor a comparative instead of a descriptive or correlational study. Knowing what your institution demands is essential in choosing an appropriate research topic.

- Explore scientific papers. Journal articles are a great way to find the critical areas of interest in your field of study. You can choose from a wide range of journals such as The Journal of Musicology and The Journal of the Royal Musical Association . These resources can help determine the direction of your research.

- Determine your areas of interest. Choosing a topic you have a personal interest in will help you stay motivated. Researching music-related subjects is a painstakingly thorough process. A lack of motivation would make it difficult to follow through with your research and achieve optimal results.

- Confirm availability of data sources. Not all music topics are researchable. Before selecting a topic, you must be sure that there are enough primary and secondary data sources for your research. You also need to be sure that you can carry out your research with tested and proven research methods.

- Ask your colleagues: Asking questions is one of the many research skills you need to cultivate. A short discussion or brainstorming session with your colleagues or other music professionals could help you identify a suitable topic for your research paper.

What’s the Difference Between a Research Topic and a Research Question?

A research topic is a particular subject area in a much wider field that a researcher chooses to place his emphasis on. Most subjects are extensive. So, before conducting research, a researcher must first determine a suitable area of interest that will act as the foundation for their investigation.

Research questions are drawn from research topics. However, research questions are usually more streamlined. While research topics can take a more generic viewpoint, research questions further narrow the focus down to specific case studies or seek to draw a correlation between two or more datasets.

How to Create Strong Music Research Questions

Strong music research questions must be relevant and specific. Music is a broad field with many genres and possible research areas. However, your research question must focus on a single subject matter and provide valuable insights. Also, your research question should be based on parameters that can be quantified and studied using available research methods.

Top 10 Music Research Paper Topics

1. understanding changes in music consumption patterns.

Although several known factors affect how people consume music, there is still a significant knowledge gap regarding how these factors influence listening choices. Your music research paper could outline some of these factors that affect music consumer behavior and highlight their mechanism of action.

2. Hip-hop Culture and Its Effect on Teenage Behavior

In 2020, hip-hop and RnB had the highest streaming numbers , according to Statista. Without a doubt, hip-hop music has had a significant influence on the behavior of young adults. There is still the need to conduct extensive research on this subject to determine if there is a correlation between hip-hop music and specific behavioral patterns, especially among teenagers.

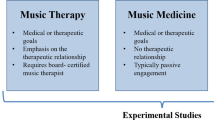

3. The Application of Music as a Therapeutic Tool

For a long time, music has been used to manage stress and mental health disorders like anxiety, PTSD, and others. However, the role of music in clinical treatment still remains a controversial topic. Further research is required to separate fact from fiction and provide insight into the potential of music therapy.

4. Contemporary Rock Music and Its Association With Harmful Social Practices

Rock music has had a great influence on American culture since the 1950s. Since its rise to prominence, it has famously been associated with vices such as illicit sex and abuse of recreational drugs. An excellent research idea could be to evaluate if there is a robust causal relationship between contemporary rock music and adverse social behaviors.

5. The Impact of Streaming Apps on Global Music Consumption

Technology has dramatically affected the music industry by modifying individual music consumption habits. Presently, over 487 million people subscribe to a digital streaming service, according to Statista. Your research paper could examine how much of an influence popular music streaming platforms like Spotify and Apple Music have had on how we listen to music.

6. Effective American Music Education Practices

Teaching practices have always had a considerable impact on students’ academic success. However, not all strategies have an equal effect in enhancing learning experiences for students. You can conduct comparative research on two or more American music education practices and evaluate their impact on learning outcomes.

7. The Evolution of Music Production in the Technology-driven Era

One of the aspects of music that is experiencing a massive change is sound production. More than ever before, skilled, tech-savvy music producers are in high demand. At the moment, music producers earn about $70,326 annually, according to ZipRecruiter. So, your research could focus on the changes in music production techniques since the turn of the 21st century.

8. Jazz Music and Its Influence on Western Music Genres

The rich history of jazz music has established it as one of the most influential genres of music since the 19th century. Over the years, several famous composers and leading voices across many other western music genres have been shaped by jazz music’s sound and culture. You could carry out research on the influence of this genre of music on modern types of music.

9. The Effect of Wars on Music

Wars have always brought about radical changes in several aspects of culture, including music styles. Throughout history, we have witnessed wars result in the death of famous musicians. If you are interested in learning about music history in relation to global events, a study on the impact of wars on music will make an excellent music research paper.

10. African Tribal Percussion

African music is well recognized for its unique application of percussion. Historically, several tribes and cultures had their own percussion instruments and original methods of expression. Unfortunately, this musical style has mainly gone undocumented. An in-depth study into ancient African tribal percussion would make a strong music research paper.

Other Examples of Music Research Topics & Questions

Music research topics.

- Popular musical styles of the 20th century

- The role of musical pieces in political movements

- Biographies of influential musicians during the baroque period

- The influence of classical music on modern-day culture

- The relationship between music and fashion

Music Research Questions

- What is the relationship between country music and conservationist ideologies among middle-aged American voters?

- What is the effect of listening to Chinese folk music on the critical thinking skills of high school students?

- How have electronic music production technologies influenced the sound quality of contemporary music?

- What is the correlation between punk music and substance abuse among Black-American males?

- How does background music affect learning and information retention in children?

Choosing the Right Music Research Topic

Your research topic is the foundation on which every other aspect of your study is built. So, you must select a music research topic that gives you room to adequately explore intriguing hypotheses and, if possible, proffer practically applicable solutions.

Also, if you seek to obtain a Bachelor’s Degree in Music , you must be prepared to conduct research during your study. Choosing the right music research topic is the first step in guaranteeing good grades and delivering relevant, high-quality contributions in this constantly expanding field.

Music Research Topics FAQ

A good music research topic should be between 10 to 12 words long. Long, wordy music essay topics are usually confusing. They can make it difficult for readers to understand the goal of your research. Avoid using lengthy phrases or vague terms that could confuse the reader.

Journal articles are the best place to find helpful resources for your music research. You can explore reputable, high-impact journal articles to see if any research has been done related to your chosen topic. Journal articles also help to provide data for comparison while carrying out your research.

Primary sources carry out their own research and cite their own data. In contrast, secondary sources report data obtained from a primary source. Although primary sources are regarded as more credible, you can include a good mixture of primary and secondary sources in your research.

The most common research methods for music research are qualitative, quantitative, descriptive, and analytical. Your research strategy is arguably the most crucial part of your study. You must learn different research methods to determine which one would be the perfect fit for your particular research question.

About us: Career Karma is a platform designed to help job seekers find, research, and connect with job training programs to advance their careers. Learn about the CK publication .

What's Next?

Get matched with top bootcamps

Ask a question to our community, take our careers quiz.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Paper writing help

- Buy an Essay

- Pay for essay

- Buy Research Paper

- Write My Research Paper

- Research Paper Help

- Custom Research Paper

- Custom Dissertation

- Dissertation Help

- Buy Dissertation

- Dissertation Writer

- Write my Dissertation

- How it works

200 Best Music Research Paper Topics For Students

Music research topics are an excellent opportunity to trace the history of the development of individual genres or entire eras. You can create an essay or research paper with an emphasis on certain stylistic features, or delve deeper into the technical aspects of album making. Also, the research topics in music allow you to learn more about popular composers, musicians, and individual bands. You can find out the history of creating certain songs or finding out the nuances of the breakup of groups.

While music research paper topics seem easy, it still requires a good outline and reliable sources to gather information. The life of many musicians is very busy, so certain topics for music research papers may require a more thorough analysis. For example, you will need to research the biography and all creation stages of famous music industry personalities.

Any research topic about music should be analyzed, and only verified facts added. You should also avoid using emotional coloring and bias. And don't forget about formatting. Any interesting music topics require clear structuring into paragraphs, lists, and subheadings.

By popular genres & styles

Individual styles are especially appreciated in research paper topics on music. You can choose the genre or group that interests you. This will allow you to get additional motivation and focus more on facts. The main challenge in this case is to find authoritative sources.

- The impact of rock and roll on the modern music industry.

- The basic concepts of creating musical songs.

- Rock performers and their popularity in society.

- Reasons for the negative attitude towards the rock vocalist.

- Rock musicians and problems with the law.

- The nuances of alcohol addiction of rock musicians.

- The main features of creating rock songs.

- Musical agitation as the main motive of rock songs.

- The main reasons for making rock songs.

- Symbiosis of rock and classical music.

- Rock performers and popular musicians.

- The analysis of the creative personality on the example of Kurt Cobain.

- The modern musical trend in culture.

- Top 10 most popular metal groups.

- Why has metal music become so popular?

- The mix of traditional music and heavy metal.

- Analysis of lyrical constructions of metal performers.

- The symbiosis of musical instruments in metal music.

- The analysis of seventh chords in the construction of metal songs.

- The influence of metal on other genres.

- The symbiosis of metal and pop music.

- The influence of metal vocalists on American culture.

- The symbiosis of genres as the reason for the creation of metal.

- The modern icons of the metal scene.

- The best metal bands in the last thirty years.

- The analysis of the dynamics of the popularity of metal bands.

- The modern concerts on the example of metal bands

- Female vocalists in pop music.

- The reason for the creation of numerous female musical groups.

- Pop music as a tuning fork of public morality.

- Why is pop music degrading?

- How can pop music be used to improve college grades?

- The nuances of using pop music in contemporary American culture.

- How can pop music be used to improve mood?

- The symbiosis of pop music and rap culture.

- How does contemporary pop music affect young people?

- The study of pop music in the context of the social culture of Harlem.

- The classic examples of pop artists.

- Madonna: the most popular popes of personalities.

- The analysis of the popularity of Britney Spears.

- Pop icons of the past decade.

- Hip-hop as the basis of the movement for social equality.

- The origins of hip-hop and the reasons for its popularization.

- How does hip-hop affect contemporary pop artists?

- The analysis of hip-hop performers on the example of the best vocalists of the decade.

- How does hip-hop allow athletes to train?

- Modern hip-hop and new musical trends.

- The symbiosis of hip-hop and metal music.

- How does hip-hop motivate people for sporting achievements?

- The analysis of hip-hop performers on the example of female vocalists.

- Modern hip-hop and its impact on youth.

- The main aspects of the integration of hip-hop music in the modern community.

- All technical aspects of creating hip-hop music.

- The classic approach to the formation of hip-hop motives.

- The analysis of the structure of hip-hop songs.

- The best hip-hop artists of the last decade.

- The stages of the formation of jazz as a separate musical genre.

- Why is jazz so popular these days?

- The nuances of studying jazz musical combinations.

- How Jess influences the structuring of student learning.

- The nuances of jazz performers in modern America.

- The best American jazz performers.

- Jazz as the most structured musical theory.

- How can you quickly learn to create jazz compositions?

- The influence of jazz on the cultural and political elite of the United States.

- Can jazz replace other musical styles?

- Jazz fusion as an example of musical prowess.

- The technical aspects of creating a pentatonic scale in a jazz style.

- The selection of jazz musicians.

- The development of jazz in the United States.

- The main reasons for the popularization of jazz in modern society.

- Blues and its influence on the development of the music industry.

- The symbiosis of blues and jazz.

- Can the Blues be compared to classical music?

- How do contemporary artists use the Blues in pop music?

- Historical context creation of blues compositions.

- How does the Blues affect rock music?

- Can the Blues help students learn?

- How blues musicians are developing in the USA.

- Can blues be used as a springboard for classical music production?

- The best US blues artists of the last 20 years.

- Blues performers of the last ten years.

- The influence of the blues on the formation of other genres.

- The analysis of the statistical popularity of the blues.

- The critical aspects when creating Blues compositions.

- The selection of blues parties when creating music.

- The influence of classical music on pop culture.

- The classical music and the best composers of the last century.

- Beethoven and his best works.

- How did Mozart influence classical music?

- Is the symbiosis of jazz and classical music possible?

- The structure of making classical music.

- The stages of the formation of classical music in modern society.

- Can you replace pop culture with classical music?

- How does classical music affect the psychological state of people?

- The classical music and symbiosis with opera.

- The basic concept of the analysis of classical music.

- A technical comparison of the mastery of classical composers.

- The choice of classical music for the mood.

- The classical music and its influence on rock culture.

- The main technical aspects of creating a score.

The region is important for those looking for musical topics for research paper. Most genres of European music and some information about composers are open to general use. If your research topic on music is aimed at analyzing the Arab countries, then you will need more time looking for reliable information. The fact is that not all Muslim archives are in the public domain.

Western music

- The features of musical motives of Western music.

- The history of Western music with real examples.

- How has Western music changed over the past two hundred years?

- Is it possible to combine Western music with European motives?

- The features of the use of traditional Western musical instruments.

- How do Western countries use music for meditation?

- Western music in the context of modern society.

- The role of Western music in the life of native people.

- How melodic is oriental music?

- The stages of the formation of Western music in American culture.

European music

- European music and modern trends.

- British pop bands and their worldwide popularity.

- How popular are German pop bands in the USA?

- European music and national musical instruments.

- How does European music affect well-being?

- The analysis of European music with specific examples.

- Top 10 of the greatest European musical groups.

- The analysis of European music on the example of instrumental groups.

- The best pop music performers in Europe.

- How does pop music influence the development of culture?

Asian music

- Asian music: the example of ethnic trends.

- The influence of Asian music on world culture.

- The main musical instruments of Asia.

- Can you compare Asian music with European motives?

- How has Asian music changed over the past hundred years?

- The nuances of creating Asian music.

- How does Asian music influence contemporary cinema?

- The best Asian performers.

- Top 10 Asian vocalists who have conquered the whole world.

- Do national instruments influence the creation of Asian music?

By history periods

You can use music appreciation research paper topics to analyse a specific period in history. Baroque, Renaissance and other eras are especially relevant for research as they allow you to see the history of the development of music. You can concentrate on a specific time period and the most famous composers.

- Medieval music and its influence on the Crusades.

- The major trends in the medieval music industry.

- The influence of kings on the creation of medieval music.

- The main musical instruments in medieval Europe.

- Musical instruments in Central Asia during the Middle Ages.

- What kind of music was popular in the Middle Ages.

- How difficult was the life of a musician in the Middle Ages?

- The analysis of medieval music on modern examples.

- How has contemporary music influenced pop culture?

- Historical aspects of the creation of medieval music.

- The influence of medieval music and culture.

- The rhythmic pattern of medieval music.

- The medieval music during the feast.

- The influence of medieval music on classical music.

- The medieval music channel and musical comparison.

Renaissance

- The dawn of musical culture during the Renaissance.

- The analysis of Renaissance music with specific examples.

- How has Renaissance music influenced contemporary pop culture?

- The analysis of Renaissance music as a constructive masterpiece.

- The nuances of Renaissance music and, most importantly, musical instruments.

- How difficult is it to reproduce Renaissance music in today's environment?

- The analysis of structural compositions of the Renaissance.

- Renaissance music as a tuning fork of public morality.

- How has music changed since the Renaissance?

- Can Renaissance music be used to create a modern instrumental ensemble?

Baroque Age (XVI-XVIII)

- The influence of politicians on the formation of music during the Baroque period.

- How has Baroque influenced contemporary instrumental music?

- The nuances of musical constructions during the Baroque period.

- How has the baroque influenced modern instruments?

- The nuances of the Baroque in the context of the complexity of musical compositions.

- The main effect of the Baroque in contemporary music.

- The historical aspects of the creation of the Baroque as a separate genre of music.

- The influence of the Baroque on the creation of contemporary musical groups.

- The analysis of the structure and musical motives of Baroque in detail.

- Baroque in contemporary music.

- The nuances of creating songs in the Baroque style.

Classical Age (XVIII-XIV)

- The Classical Age of music in modern society.

- How did the Classical Age influence the formation of musical trends?

- The general concept of the Classical Age in instrumental music.

- The nuances of creating music based on the Classical Age.

- How did the Classical Age influence the creation of pop culture?

- The theory of creating musical compositions on the example of the Classical Age.

- The general factors of the Classical Age in instrumental music.

- The main trends and popular instruments of the Classical Age.

- The main musical compositions of the 14th century.

- The main factors in the creation of musical compositions in the 13th century.

Romantic Era (XIV-XX)

- The Romantic Era and its impact on contemporary music.

- The main principles of structuring music into the Romantic Era.

- Features of creating instrumental compositions in the Romantic Era.

- The Romantic Era and modern music trends.

- The main factors influencing the Romantic Era in the music industry.

- Key figures in the music industry and their passion for the Romantic Era.

- How did the Romantic Era form the modern style?

- How has the Romantic Era influenced rhythmic music?

- The Romantic Era in the music industry.

- The main aspects of the formation of the Romantic Era in musical culture.

- Making marching music in the Romantic Era.

- Features of creating musical compositions.

- The technical aspects that influenced modern romantic motives.

Modern Era (XX-XXI)

- Jazz music as a phenomenon of the modern roar the influence of the modern era on instrumental music.

- Technical aspects of hip-hop and Reggae.

- How is contemporary classical music created?

- Can modern music genres be combined to create something new?

- Why is the modern music industry stagnating?

- The aspects of contemporary music.

- How does instrumental music affect culture?

- Contemporary music and technical innovation.

- How is contemporary music created?

- The nuances of creating hip-hop albums.

How To Write On Music Related Research Topics

By choosing topics about music for an essay, you get the opportunity to prepare a detailed paper work with facts, genre nuances and detailed biographies of famous musicians. You need to stick to the formatting and your outline. Find reliable information for music history research topics and talk about the emergence of certain genres.

Music business research topics are especially important, as you need to consider not only the stylistic but also the commercial nuances of the bands. For example, you can prepare detailed data on annual music tours or album sales.

All music appreciation presentation topics require detailed factual focus, which can be difficult for many people. If you are not ready to do it yourself, then we can help you.

Our service will solve your problem with music research topics high school. We also guarantee that you will get a good grade. We will help you organize all the nuances so that your music history paper topics become a reason for pride and high scores.

An Inspiration List

- popular music | Description, History, & Facts | Britannica

- History of music

- Music History from Primary Sources

- Brief History of Music: An Introduction

- How Music and Instruments Began

206 Best Music Research Topics That Rock The Stage

Music is one of the greatest sensations in human life. If you are writing a music research paper, you have to make sure that the topic is eye-catching. Most importantly, it should move and make you dance yourself. The topic that you are not interested in will not only make you weary, but the results would be unsatisfying too.

That is why our writers have found music research paper topics for you to save the day. We love music very much, and so our team offers an Academic paper writing service , so you can trust the word.

Table of Contents

Music Research Topics: History, Technical Music, Contemporary And More

Although our writers mainly offer research paper writing services , they did not hesitate for a bit when we asked them to come up with some music research topics for you. You can use any of these 206 topics for free and modify them to fit your needs and match your taste. Read on!

Music History Research Topics

- Use of songwriting in relation to the political and social situations in Nazi Germany and the French Revolution

- Musical Education between two centuries

- Evolution in the definition of music over the centuries

- Birth of Music in Mesopotamia

- Impact of Arab-Andalusian music on renaissance

- Folklore bands of wind music, a cultural manifestation of the people and for the people

- Harmonic implications studied by Pythagoras

- Music from Ancient Greek

- Importance of Music in Greek Mythology

- Song of the Sirens in the evolution of music

- Greece, music, poetry, and dance

- Athens was a center of musical poets in the BC era

- Classical Greek Style Music

- Yanni: A Musician that fuses Modern and Classical Greek Music into one

- Role of Music in Greek Tragedy

- Famous musical-dramatic pieces

- Heroic poets: Arab poets that formed the basis of European music

- Performances in amphitheaters by singers-actors-dancers

- Classical musician considered himself more of a performer than an author

- Ritual dance with kettledrums around the fire: Musical Traditions of Pagan cultures

- Classification of primitive musical instruments

- Music in China

- Music in Mayan Tradition

- Apache and Native American Music

- How Africans and Columbians formed the modern American music

- The musical theory and the instruments used in Japan

- Bagaki for Japanese Emperor ceremonies

- Evolution of Indian Music

- Music in the Mughal Empire

- Anarkali: A musical myth with a royal background

- Christian Music, Hymns and Choirs

Read More: Psychology Research Paper Topics

Technical Music research topics

- Similarity measures, including rhythmic and melodic similarity.

- Phylogenetic analysis of music.

- National Center for Music Diffusion

- Mathematical measures of rhythmic complexity and syncopation

- Musical transformations of rhythm and melody

- Automatic analysis of traditional music, Afro-Cuban, Brazilian and African music

- The mathematical theory of rhythm

- Musical constructivism

- Model models (MM) and counter models (CM)

- The role of sound design in video games and its application to contemporary independent works

- Mathematical and computational modeling of musical phenomena (grouping, phrasing, tension, etc.)

- A mathematical theory of tuning and temperament systems

- Teaching mathematics through art

- Music visualization

- History of Modern Columbian Music

- Acoustic-instrumental composition, electroacoustic and sound art

- Interpretation and musical investigation

- sound production

- Transcription and music editing

- Recovery of musical heritage

- Studies of music, literature, culture, and colonial anthropology

- Music by European composers of the 16th century (Renaissance)

- Education and technology in educational scenarios of musical training

Read More: Finance Research Topics

Music Argument Topics

- Visual Media Music Studio

- Music as an important expression in the history of the world

- Conversations about music, culture, and identity

- The architectural space as a link between music and the citizen

- Music Schools for children and young people with limited resources

- Role of practice and need for devotion in learning and acquiring musical skills

Read More: Accounting Research Topics

Contemporary Music research topics

- Impact of Coke Studio: From Pakistan to take over the world

- Effects of Modern Music on Youth

- Musical Martyrs: Freddie Mercury, Amy Winehouse, Elvis Presley

- Music of Hans Zimmer

- Production and exhibition of contemporary music

- Entertainment and music centres

- Non-formal music schools

- Music and education today

- Contemporary Mexican music

- Satanism movement in modern music

- Western musical history and “modern” music

- Journey of Music: From the Medieval Family to the Modern Family

- Importance of Opera in the modern age

- Evolution of music over time: From orchestra to electric

- Self-management and promotion of independent music

- Music of electric musicians: Alan Walker, Serhat Durmus, Chain Smokers

- Modern Music, A Wonderful Expression

- The idiomatic reality of the English language

- Modern Music in the United States

- Current music pedagogy

- Music education in the twentieth century

Read More: Research Paper Topics

Classic Music Research Topics

- Classic music of South Asia

- Classic music of Africa

- Classic Arab music, the influence of Soad, Um Kalthum

- What makes classic music so important and why do we still have to reserve it?

- Music of Beethoven, Mozart and Brahms

- Use of classic music in the film

- Beethoven: How he lived, composed and died

- Life and music of Mozart

- Classical music by Afro-American women

- Music in classical films

- Greatest compositions of 19-20th centuries

- Style and compositions of Einaudi

- Music during the classical period

- Classical Music Criticism

Read More: Business Research Topics

African music research topics

- The Effects of Slave Music on American History and African-American Music

- The use of Afro-Caribbean rhythms for the construction of jazz musical moments

- African folk music of Cuba

- History of African-American Popular Music

- African diversity in music

- The study of the oral and musical traditions of the Afro-Mexicans

- Studies of African Musical History and its Relationship with modern society

- South African influences on American music

- African music in Mali

- African music: South Africa

- Music of the Middle East and North Africa

Read More: Nursing Research Topics

Pop Culture Music Research Topics

- The pedagogical models of popular music

- Music throughout the decades of musicals

- Brad Paisley and Country Music

- The Effects of Music on the popular culture

- Hip-hop/rap music: One of the most popular musical genres

- The influence of rap music on teenagers

- Irish Music: Music and Touch Other Irish Dance Music

Read More: Qualitative Research Topics

Music Theory Topics

- Genre and music preferences

- The effect of instrumental music on word recall memory

- Sample Music and Wellness

- The music industry

- The Theme of Death in a Musical

- The Effects of Globalization on MusicMusic psychology research topics

- The potential of music therapy to develop soft skills at the organizational level

- Listening to music as a way to relieve stress for teens

- The impact of theatricality within contemporary popular music concerts of the psychedelic, glam, and progressive rock genre

- Trying music as therapy

- How music can help students with ADHD (Attention Deficit Hyper Disorder)

- How can music help reduce work stress and maintain a healthy work environment

- Musical manifestations of man consist of the externalization

Read More: US History Research Topics

Music Education Research Topics

- New pragmatism in music education

- Importance and effects of musical education

- Philosophy of Music Education

- Music, a tool to educate

- Competencies in music education

- Music as a strategy to encourage children’s effective learning

- Interconnection between music and education

- Philosophy of musical education

Read More: High School Research Paper Topics

Persuasive Speech Topics About Music

- The music is a true reflection of the essay of American society

- Music and Its Effects on Society

- Matter Of Metal Music

- Beethoven’s Twelfth Symphony: the second movement of the symphonic essay

- Messages in music

- The benefits of music trial

- Does music affect blood pressure?

- Music Industry Research: An Epic Battle With Youtube

- Entertainment and education Via music

- Whitman’s music as a means of expression

- Music and its Effect on the World

- Music: Essay on Music and Learning Disabilities

Read More: Political Science Research Topics

Music Controversial Topics

- Whether or not profanations in music corrupts our youth

- Drugs and rock and roll

- Piracy and the music industry

- Music censorship is a violation of freedom of expression

- Music censorship

- The use and overuse of the music

Read More: Criminal Justice Research Paper Topics

Music Industry Topics

- Freedom of expression and rap music

- Censorship in the music industry

- Influence of music on culture

- Analysis of Iranian film music

- Analysis of the Turkish Music Industry

- Analysis of the South Asian Music Industry

- Coke Studio Making and Global Impact

- The digital revolution: how technology changed the workflow of music composers for media

- Video music as matter in motion

- Acoustic and interpretive characteristics of the instruments

- The study of musical composition based on pictorial works

- Musical prosody of the interpretation

Read More: Social Work Research Topics

Arab Music Research Paper Topic

- Arab music industry: Evolution after colonialism

- Music of Middle

- Umm Kulthum: Effects on global music

- How the Arab music still impacts Asian and American Music

- Effects of Arab music on popular French music

- Turkish and Arab Music: A Beautiful Cultural Fusion

- Arab Heroic Poets of Andalus and how they formed modern European music

- Revival of Arab music through electrical genre

Read More: Medical Research Topics

Music Thesis Topics

- Film Industry Classical Music

- Finding Meaning in a Musical

- Music and its effect on my interpretation

- How music can interact with politics

- Musical phrases and the modal centers of interest of the melody

- Effect of ambient music on sleep trials

- The main characteristics of the musical organization

- Study Of Cadences And Other Harmonic Processes In The Light Of Consonance And Dissonance Theories

- Theoretical-experimental Study Of Percussion, Wind And String Instruments

- Recognition Of The Instruments Of The Orchestra

- Compositive Algorithms Using Unconventional Musical Magnitudes

- Development Of A Microtonal Harmony As A Generalization Of The Common Practice Period

- Mechanism related to the recognition of specific emotions in music

- Musical emotion (emotion induction)

Read More: Biology Research Paper Topics

High School Research Paper Topics on Music

- Correlation Between Personality and Musical Preferences Essay

- Effects of Rock Music on Teenagers

- Does popular music stay popular?

- The effect of music on the interpretation of a musical

- Musical activities in a spiral of development

- Adolescents in the understanding of contemporary processes of music

- Musical activities in the content system

- Music and the value of responsibility

- Presentation of musical fragments, Performance of live or recorded musical instruments

- Life stories of composers and musical personalities such as Mozart and Beethoven

- Presentation of music related to tastes and socio-educational reality

- Exhibition of musical fragments and execution of instruments

- Presentation of different types of music, the performance of musical instruments live or recorded

- Experience composing music, with lyrics, instrumental or with sounds from the environment, what musical genre or type of sound production does it represent?

- The practice of the studied musical instruments, record the meanings that guide your performance and preparation as a student and for life

- Why is compliance with the vocal techniques of singing a duty that must be assumed consciously?

- Does all music express sound? Does every sound express a genre or type of music?

- Practice sound emission and tuning techniques

- Why is it important to make movements according to the type of music you listen to?

Music is one of the greatest inventions of the human race. All good music makes your heart beat a little faster and soothes your mind into peace. It has been evolving since the dawn of civilization, 5000 years ago in Mesopotamia. Whatever research you make about it, just make sure that it touches your heart.

If you want to save your time and get your music research paper written by us, you are in for good news. We offer the best research paper writing services in the USA. You can contact us to discuss your research paper. You can also place your order and we can start working on your research paper right away.

Order Original Papers & Essays

Your First Custom Paper Sample is on Us!

Timely Deliveries

No Plagiarism & AI

100% Refund

Try Our Free Paper Writing Service

Related blogs.

Connections with Writers and support

Privacy and Confidentiality Guarantee

Average Quality Score

- Write my thesis

- Thesis writers

- Buy thesis papers

- Bachelor thesis

- Master's thesis

- Thesis editing services

- Thesis proofreading services

- Buy a thesis online

- Write my dissertation

- Dissertation proposal help

- Pay for dissertation

- Custom dissertation

- Dissertation help online

- Buy dissertation online

- Cheap dissertation

- Dissertation editing services

- Write my research paper

- Buy research paper online

- Pay for research paper

- Research paper help

- Order research paper

- Custom research paper

- Cheap research paper

- Research papers for sale

- Thesis subjects

- How It Works

160 Hot Music Research Paper Topics For You

Music has been part of human beings since time immemorial. As it evolves, everyone has a specific taste for a specific song, genre, or musical instrument. Some of the top genres include roots, reggae, hip-hop, jazz, and rock music. The evolution and popularity of music have made it become one of the important subjects taught in schools worldwide.

If you are in college, pursuing music as a career, one of the important tasks when writing every research paper is picking the right topic. However, selecting an exciting music topic has always been a challenge for most students. To help you with the problem, we have listed the top 160 music research topics. Go ahead and select any of them or tweak them to reflect your preference.

How To Select The Best Music Topics For Research Paper

- Special Tips to use when Selecting Research Topics about Music

Top Music Research Paper Topics

Music argument topics, music history topics, hip hop research paper topics, jazz research paper topics, music appreciation research paper topics, music education research topics, pop culture research paper topics, rap topics ideas, fun music topics.

The ability to come up with the right topic for your music research paper is an important skill that every student should develop. Here are some steps to follow when looking for the most appropriate music research paper topics.

- Go for the research topic about music that is interesting to you.

- Only pick the music topics to write about if they have ample resources.

- Ensure only to pick interesting music topics that meet your college requirements.

- Go for the topic that you can comprehensively write on.

Special Tips to Use When Selecting Research Topics About Music

If you want to enjoy every moment working on your research papers, it is advisable to cast eyes beyond what is easy and popular. This means trying to check interesting topics that will allow you to answer tough research questions about music. Here are additional tips to help you:

- Brainstorm the current music topics.

- Comprehensively research the subject of interest before starting to develop the topics.

- Consider starting with music thesis topics and finally narrow to the one you consider the best.

- Follow current affairs in the music industry.

- A closer look at the evolution of music over the years.

- Analyzing the most influential musicians of the 20th century.

- Analyzing the relationship between music and dance.

- A closer look at the most lucrative careers for musicians.

- Music and health: What is the relationship?

- How does music impact fashion?

- Which music genre has impacted music more?

- A closer look at music marketing for different genres.

- Does music help learners concentrate when doing assignments?

- How does music affect clothing style?

- Evaluating the influence of music on culture in a country of choice.

- Analyzing the use of music for advancing political propaganda.

- How has production in music changed in the recent past?

- Drawing the connections between popular and contemporary music.

- Comparing music in the US with that of Latin America?

- In what ways are music and poetry related?

- Classical music: Does it still play a major role in music production today?

- Evaluating the main processes used in music production today.

- Analyzing the importance of music theory in music production.

- Music production: Why do some musicians ask others to write their songs?

- Pirating is one of the biggest threats to the growth of the music industry.

- Music can be a great rehabilitation procedure for inmates.

- The cost of music production is a major obstacle to the faster growth of the industry.

- Exploring the factors that have made Chinese music develop slower compared to western music.

- Evaluating the most important skills that an artist needs to produce a song.

- How does music compare to other types of media today?

- How does music impact the way people think?

- What are the most notable challenges in music production?

- How does creating music impact how people think?

- Comparing the roles of women in contemporary and modern music.

- What challenges do minority groups have in music production?

- What are the legal implications of downloading music?

- Music production: How does contemporary and modern music production differ?

- What role do social media platforms play in music distribution?

- Evaluating common traits of people who like listening to classical music.

- How does music affect teen behavior?

- Is music helpful in your daily activities?

- Analyzing music as a tool of advertisement.

- The future of music.

- Exploring the significance of music in education.

- Assessing the contribution of music to the US economy.

- What is the contribution of music to the US economy today?

- A closer look at the impact of pop music on people’s culture.

- What are the key differences between 21 st and 20 th -century pop music?

- How is music production affected by different laws in the US?

- Analyzing the ethical impacts of downloading music.

- Analyzing the evolution of symphonic music.

- A closer look at the use of classical music in the video production industry.

- Women who played significant roles in classical music.

- What differentiates Mozart music from other types of classical music?

- A comparative analysis of two top classical musical producers.

- The economic impacts of free music downloading.

- How does revenue from music and film production compare?

- Analyzing the main characteristics of country music.

- Exploring the relationship between drugs and psychedelic rock.

- A closer look at the merits and demerits of capitalistic perception of the music industry.

- Analyzing the modern approaches to songwriting.

- How has jazz impacted the American culture?

- Exploring the roots of African-American melodies.

- A historical comparison of hip-hop and jazz.

- What does it take for a musician to succeed today?

- Should the government fund upcoming artists?

- Which classical artist has had the biggest impact on you?

- The impact of the British music invasion of the US market.

- How is music used in war?

- Comparing high and low culture in the current music.

- Exploring the difference between music and poetry.

- Comparing the most lucrative careers in the music industry.

- What impact does music has on children’s cognitive development?

- Analyzing the history of American music education.

Different forms of music exist that we learn in various genres. In many institutions, music argument topics are assigned to know a student’s response regarding their opinions towards a genre. These music types range from classical to country, pop, jazz, blues, afro beats, and rock music. Understanding each one and knowing examples will help students choose the right argument. Some topics include;

- Evolution of rock music in comparison with rap music.

- What is behind the various instruments and their history in creating a particular genre of music?

- How the merging of societies and cultures influence native music.

- Reasons why rock music was used in the cinemas for long periods instead of another genre.

- The effect of globalization on pop and jazz music.

- The prominence of jazz music in the US over a short time.

- How black women fought and argued over social injustice through jazz music.

- Does jazz music celebrate black culture or glorify oppression?

- Women or men – who have played more roles in the development of classical music?

- The prominence of rap music in the present generation. Result of depreciated quality of music or evolution?

Music contains a broad history, with studies on performance, composition, reception, and quality over time. The history of music is usually intertwined with the composer’s life and development of the particular genre they create. Some music history topics include;

- History of pop music in America in the 20th century.

- Musical styles of England in the 21st century.

- The history of afro-beat and their development across West Africa and the rest of the world.

- Historical performance of music: the study of Beethoven’s works.

- History of Jazz and its development in the United States.

- Music in Ancient cultures: Native music

- The role of women in music development

- History of classical music

- Different types of music in the 19th century

- Important of renaissance music in history.

Present-day hip-hop music developed its culture and lyrical pattern. The style has evolved and gotten more refined and flexible over the years. Going into its history, many facets inspired it to what it has become today. Some hip hop research paper topics include;

- The history and structure of hip hop music

- Hip hop and its ties with poetry

- Hip hop culture and fashion today

- Old school vs. new school hip hop

- Rap and hip hop culture

- Violence in rap and hip hop

- The evolution of hip hop and rap music

- The positives and negatives of hip hop and its culture

- Bland misogyny in hip hop music lyrics

- The role of hip hop in white and black cultures

Jazz has a rich history in black culture and black liberation and its development led to major cultural shifts across the world. This music genre is refined and is deep-rooted in black history. It is music for the soul. Here are some jazz research paper topics;

- What is jazz music? An explanatory approach to its culture and relevance.

- History of jazz music.

- Jazz music and pop culture

- Jazz music and its listeners: Who listens to modern jazz?

- Why 1959 was a turning point in the history of jazz?

- The significance of jazz on the civil rights movement

- The history of jazz dances in America

- Some of the best jazz musicians of the 20th century

- Development of jazz music into the post-modern era.

- A study and review of the different dimensions of jazz.

Research topics on music appreciation mainly look into the reception and criticism of a given piece of music. This is achieved while examining vital music facets such as rhythm, performance, melody, and instrumentation. Here are some good examples of music appreciation research paper topics.

- The best generations of music

- The greatest musical icon: the life and times of Michael Jackson

- Music appreciation in the 21st century

- Music philosophy and its value

- Notable mentions in music evolution

- The theory of music and its importance

- The unique and different eras of music

- Music and its welcomed effect on the brain

- Music in different continents

- The love for opera

Music education is integral and important to enlightening younger generations about musical history, culture, evolution, and present significance to society. Without music to decorate our lives, time is just a dull passage of raw emotions and existence. Music knowledge and understanding is vital, and it affects our culture and way of life. Here are some music education research topics;

- Scope of music therapy

- The role of music in political movements

- Music and society

- Music business and management

- Functions of music therapy relating to intellectual improvement

- Significance of music education

- Contemporary music and its controversies

- Music and human emotion

- Technology and the evolution of music production

- The birth and prominence of music videos

Pop culture comprises numerous categories, including music, fashion, social media, television, language, and many more. It has gradually become an integral facet of our society. It has its perks and criticisms, but it is here to stay and makes our lives a lot more interesting. Some noteworthy pop culture research paper topics are;

- What makes pop culture popular?

- Is pop culture bad or good for the present society?

- Does pop culture disrupt moral values?

- Modern technology and its effects on pop culture

- How does American pop culture affect the global economy?

- Technology and ethical issues in pop culture

- Pop culture and its educational benefits

- How is humanity’s development expressed in pop culture?

- Is it necessary to study pop culture?

- Pop culture and its demerits to the society

Rap has become a mainstay in our music genre today. After its rocky start, it has fully become integrated into our music culture and lifestyle. Rap is an expression of life situations, love, religion, family, and who we are. Some rap topics ideas include;

- Rhythm and melody

- The art of flow and rhyme in rap

- Rap dimensions: tone and delivery

- Evolution and history of rap music

- The negatives and positives of rap music

- Contemporary rap music

- The role of rap music in black communities

- Does rap incite and encourage black violence?

- The history and origin of rap

- Rap as a means of expression

Music will always be an exemplary form of self-expression and art. Over the years, it has progressed and transformed through various dynamics. Today, at least a hundred music genres out there are fun and beautiful in their diversity. There are many fun music topics, and some of them include:

- How music helps fight stress and psychological problems

- The most iconic musical instruments for creating music

- Which music inspires you and why?

- Music in the 21st century

- The most common and popular type of music

- Reflection of social issues in music

- A couple of reasons to listen to music

- What differentiates good music from bad music?

- Different dimensions of music

- Imagining a non-music world.

After selecting the best research topic about music, the next step is writing your paper. This task is even more monumental than selecting the topic. Here, you need to craft an outline, have impeccable writing skills, and complete your task within the stipulated timelines. Is this too much? If you find it a challenge to write your paper, the best option is seeking writing help. The assistance is provided by affordable writing experts who understand how to create a good music thesis statement and have an impressive experience to craft winning papers. Do you want assurance of high grades? If “yes,” it is time to work with experts!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Diverse Music Essay Topics for Students and Music Enthusiasts

Table of contents

- 1 How to Write an Essay on Music

- 2.1 Argumentative Essay Topics about Music

- 2.2 Topics for College Essays about Music

- 2.3 Controversial Topics in Music

- 2.4 Classical Music Essay Topics

- 2.5 Jazz Music Essay Topics

- 2.6 Rock and Pop Music Essay Topics

- 2.7 Persuasive Essay Topics about Music

Music is a magical world of different sounds and stories. When we talk about music, there are so many things we can explore. Writing essays about sound lets us share our feelings and thoughts about this wonderful art. In this collection, you will find 140 music essay topics.

These topics are carefully chosen to help you think and write about sound in many exciting ways. Whether you love listening to music or playing an instrument, these topics about music for an essay will spark your creativity. They cover everything, from your favorite songs to the history of music. So, get ready to dive into the sound world with these fun and interesting essay ideas!

How to Write an Essay on Music

Writing an essay about sound can be a fun and exciting way to express your thoughts and feelings about this amazing art form. Whether you are working on college essays about music, or research paper topics on music, here are some steps to help you create a great piece of writing.

- First, choose a topic that you are passionate about. It could be anything from your favorite musician to a specific sound genre. For a college essay about sound, you might want to share a personal story about how music has impacted your life. For argumentative essay topics about sound, consider issues like the importance of sound education or the effects of music on the brain. If you’re working on a research paper on sound, explore the history of a certain music style or the role of sound in different cultures.

- Once you have your topic, start with some research. Look for interesting facts, stories, and opinions about your topic. This will give you many ideas and help you understand your topic better.

- Next, create an outline for your essay. This will help you organize your thoughts and keep your writing clear and focused. Start with an introduction that introduces your topic and grabs the reader’s attention. Then, write a few paragraphs that explain your main points. Each paragraph should focus on one main idea or argument. In your writing, explain things in a way that’s easy to understand. Use simple words and short sentences.

- Also, try to include examples and personal experiences to make your essay more interesting and relatable.

Need help with essay writing? Get your paper written by a professional writer Get Help Reviews.io 4.9/5

List of Topics about Music for an Essay – 40 words

Discover a world of music topics to write about in this list! From fun ideas to controversial topics in music, these essay suggestions will inspire you to explore the diverse and exciting universe of music.

Argumentative Essay Topics about Music

Dive into the world of melodies and rhythms with these essay topics about music! Whether you’re passionate about different genres or curious about the impact of sound, these argumentative essay topics will guide you to explore and express your views on various musical aspects. So, let’s get ready to write and debate about the diverse and vibrant universe of sound.

- Is Melody Essential in Every School’s Curriculum

- The Impact of Melody on Mental Health

- Should There Be More Support for Local Musicians

- The Role of Songs in Cultural Preservation

- Does Modern Melody Lack Originality

- The Effects of Sound on Productivity

- Are Music Award Shows Biased

- The Importance of Lyrics in Songs

- Should Songs Be Used in Advertising

- The Influence of Music on Fashion Trends

- Does Melody Promote a Better Global Understanding

- Should Explicit Sound Be Censored

- Are Songs Festivals Beneficial for Local Communities

- The Role of Technology in Melody Production

- Is Classical Melody Still Relevant in the Modern Era

- The Impact of Social Media on Musicians’ Success

- Should Music Be Included in Workplace Settings

- The Role of Melody in Political Movements

- Are Music Streaming Services Fair to Artists

- The Importance of Preserving Traditional Melody

Topics for College Essays about Music

Step into the rhythm of words with these research paper topics about music, perfect for college essays. These topics offer a wide range of ideas, from personal experiences to cultural impacts, inviting you to explore the profound influence of sound. They are designed to inspire deep thought and passionate writing, helping you connect your academic skills with your love for melody.

- How Sound Influences Fashion Trends

- The Role of Melody in Different Cultures

- Personal Growth Through Learning a Musical Instrument

- The Evolution of a Specific Melody Genre

- The Impact of Songs Streaming Services on Artists

- Music as a Form of Social Protest

- The Psychological Effects of Melody on the Human Mind

- The Importance of Songs Education in Schools

- The Relationship Between Melody and Memory

- How Technology Has Changed the Way We Experience Music

- The Representation of Women in Music

- Music’s Role in Personal Identity

- The Influence of Melody on Mood and Behavior

- The Resurgence of Vinyl Records in the Digital Age

- The Globalization of Music and Its Effects

- The Economic Impact of the Songs Industry

- Melody as a Tool for International Diplomacy

- The Ethics of Music Sampling and Remixing

- The Role of Melody in Film and Media

- The Future of Live Music Performances

Controversial Topics in Music

Embark on a journey through the provocative and often debated realms of music with these 20 topics on controversial topics in music. These topics are designed to stir thought and conversation, challenging you to explore the music world’s more contentious and complex aspects. From ethical dilemmas to cultural controversies, these subjects offer diverse perspectives for deep exploration and spirited discussion.

- The Impact of Song Piracy on the Industry

- Censorship in Songs and Its Effects on Artistic Freedom

- The Portrayal of Women in Popular Song Videos

- The Commercialization of Indie Melody Genres

- The Role of Auto-Tune in Modern Music

- Melody as a Tool for Political Propaganda

- The Influence of Corporate Sponsors in Melody Festivals

- The Ethical Considerations of Posthumous Melody Releases

- Cultural Appropriation in the Song Industry

- The Decline of Traditional Songs Forms

- The Relationship Between Melody and Substance Abuse

- The Effect of Digital Streaming on Melody Quality

- The Representation of Minority Groups in Mainstream Music

- The Debate Over Explicit Lyrics and Parental Advisory Labels

- The Rise of AI in Songs Creation

- The Impact of Reality Song Shows on the Industry

- The Role of Gender in Melody Award Nominations

- Melody and Its Influence on Youth Behavior

- The Sustainability of the Music Tour Industry

- The Shift in Melody Consumption From Albums to Singles

Classical Music Essay Topics

Go on an enlightening journey through the world of melodies and harmonies with these 20 music topics to research, perfect for crafting compelling college essays. These topics delve into music’s vast and varied dimensions, from its historical roots to its modern-day impact. They are designed to ignite your curiosity and inspire in-depth exploration, blending academic rigor with a passion for music.

- The Evolution of Melody Through the Decades

- The Influence of Classical Song on Modern Genres

- The Psychological Effects of Melody Therapy