Why the 2022 Philippines election is so significant

There are 10 candidates vying to replace Rodrigo Duterte as president, but only two really matter.

The Philippines goes to the polls on May 9 to choose a new president, in what analysts say will be the most significant election in the Southeast Asian nation’s recent history.

Outgoing President Rodrigo Duterte leaves office with a reputation for brutality – his signature “drug war” has left thousands dead and is being investigated by the International Criminal Court (ICC) – economic incompetence, and cracking down on the media and his critics.

Duterte has also been criticised for his handling of the coronavirus pandemic, which has killed at least 60,439 people in the archipelago.

There are 10 people battling to replace him, but only two stand a chance of winning.

The first is frontrunner Ferdinand Marcos Jr, popularly known as “Bongbong” and the namesake of his father, who ruled the Philippines as a dictator until he was forced from office and into exile in a popular uprising in 1986.

The second is Leni Robredo, the current vice president and head of the opposition, who has promised more accountable and transparent government and to reinvigorate the country’s democracy.

“This election is really a good versus evil campaign,” University of the Philippines Diliman political scientist Aries Arugay told Al Jazeera. “It’s quite clear. Duterte represents dynasty, autocracy and impunity. Robredo stands for the opposite of that: integrity, accountability and democracy.”

What happens on election day?

Some 67.5 million Filipinos aged 18 and over are eligible to cast their vote, along with about 1.7 million from the vast Filipino diaspora who have registered overseas.

Polling stations will open at 6am (22:00 GMT) and close at 7pm (11:00 GMT). The hours have been extended because of the coronavirus pandemic and the need to avoid queues and crowds.

Once the polls close, counting gets under way immediately, and the candidate with the most votes wins. There is no second round so the name of the new president could be known within a few hours. The inauguration takes place in June.

As well as the presidential race, Filipinos are choosing a new vice president – the position is elected separately to the president – members of congress, governors and thousands of local politicians including mayors and councillors.

Politics can be a dangerous business in the Philippines and there is the risk of violence during both campaigning and the election itself.

In one of the most horrific incidents, dozens of people were killed and buried by the roadside in 2009 by a rival political clan in what became known as the Maguindanao massacre .

Who is in the running for president?

Opinion polls suggest Marcos Jr remains in the lead although Robredo appears to be closing the gap.

The 64-year-old dictator’s son attended the private Worth School in England and studied at Oxford University – Marcos Jr’s official biography says he “graduated” but the university says he emerged with a “special diploma” in social studies.

He entered politics in the family stronghold of Ilocos Norte in 1980, and was governor of the province when his father was forced out of power and democracy restored.

In 1992, he was elected to congress – again for Ilocos Norte. Three years later, he was found guilty of tax evasion, a conviction that has dogged him ever since but does not seem to have hindered his political career.

Marcos Jr was elected a senator in 2010, and ran unsuccessfully for the vice presidency six years later when he was pipped to the post by a resurgent Robredo.

On the campaign trail, Marcos Jr has talked of “unity” but has provided little detail on his policies and has avoided media interviews and debates.

His running mate is Sara Duterte-Carpio , Duterte’s daughter, who took over as mayor of Davao City from her father and is leading the field for vice president.

Robredo is the current vice president and a human rights lawyer who got into politics in 2013 after her husband – a government minister – was killed in a plane crash.

She threw her hat into the ring at a relatively late stage, and has relied on a network of pink-clad volunteers to win over voters across the archipelago.

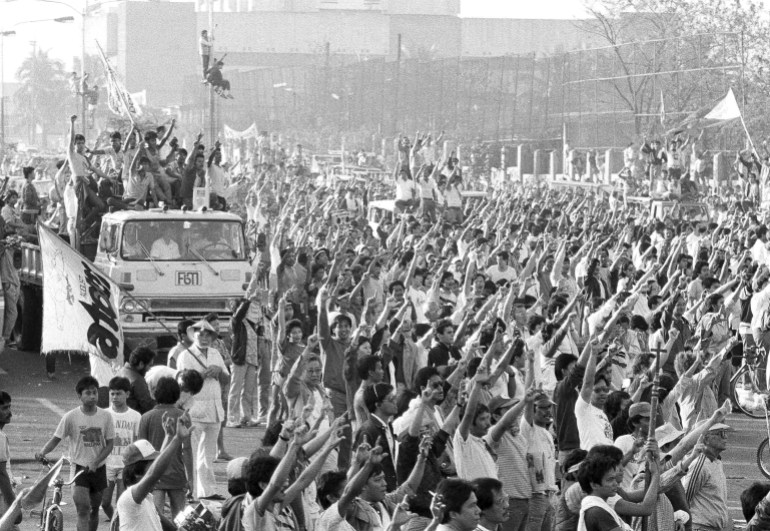

Thousands have turned out for her rallies, some of then standing for hours in their hot sun waiting to hear the presidential hopeful speak. Robredo, whose running mate is Senator Francis “Kiko” Pangilinan, is running on a platform of good governance, democracy and an end to corruption.

Other candidates include champion boxer Manny Pacquiao , Manila mayor Francisco “Isko Moreno” Domagoso, and a former police chief Panfilo Lacson.

Why would a Marcos victory be controversial?

Ferdinand Marcos became president of the Philippines in 1965, winning over Filipinos with his charisma and rhetoric, and taking control of a country that appeared at the time to be one of Southeast Asia’s emerging powerhouses.

Backed by the United States, Marcos won a second term in office in 1969, but three years later he declared martial law claiming the move was necessary to “save” the nation from communists.

For the next 14 years, he ruled the country as a dictator.

More than 3,200 people were killed – their bodies often dumped by the road side as a warning to others – and even more tortured or arbitrarily jailed, according to the US academic and historian, Alfred McCoy.

Marcos’s biggest rival, Benigno Aquino, was assassinated as he got off a plane at Manila airport.

The killing shocked Filipinos at a time when they were increasingly angry at the corruption and extravagance of the Marcos regime. Even as many lived in poverty, the Marcos family bought properties in New York and California, paintings by artists including impressionist master Monet, luxury jewellery and designer clothes.

Transparency International estimated in 2004 that the couple embezzled as much as $10bn during their years in power, and Imelda , Marcos’s wife, has become a byword for excess.

But since the former dictator’s death in Hawaii in 1989, the Marcos family have sought to rehabilitate themselves, trying to portray the dictatorship as some kind of golden age.

In 2016, Duterte allowed Ferdinand Marcos to be buried in Manila’s heroes cemetery, complete with a 21-gun salute .

Now the Duterte family is allied with the Marcos one, and their bid also has the support of other politically influential dynasties in a country where blood ties are more important than any political party.

“The meteoric resurgence of the Marcoses is itself a stinging judgement on the profound failures of the country’s democratic institutions,” academic Richard Javad Heydarian wrote in a column for Al Jazeera in December. “Decades of judicial impunity, historical whitewashing, corruption-infested politics and exclusionary economic growth has driven a growing number of Filipinos into the Marcoses’ embrace.”

Many worry the election of Marcos Jr, particularly if Duterte becomes vice president as widely expected, could herald a new era of repression.

“The two are the offspring of two strongman rulers,” Arugay said. “Can we expect restraint and inclusive government? You don’t need to be a political scientist to answer that question.”

Earlier this week, some 1,200 members of the clergy of the Catholic Church endorsed Robredo and Pangilinan describing them as “good shepherds”. At least 86 percent of Filipinos are Catholic.

“We cannot simply shrug, and let the fate of our country be dictated by false and misleading claims that aim to change our history,” they said.

Will the result be accepted?

When Marcos Jr lost the vice presidential race by 263,000 votes in 2016, he challenged the result in court.

With the stakes much higher this time around, some analysts worry he could do so again if Robredo manages to pull off a victory.

The role of social media

Filipinos are avid users of social media and the platforms have played a key – and divisive – role in the election, intensifying the more toxic elements of political campaigning.

Marcos Jr and his team have been accused of using – and abusing – online platforms.

In January, Twitter suspended more than 300 accounts promoting his campaign, which it said breached rules on spam and manipulation.

Joshua Kurtantzick of the Council on Foreign Relations says Marcos Jr has also benefited from “the legacy of Duterte, who fostered the spread of disinformation and made it easier for another strongman to win”.

Senatorial race

While all eyes are on the presidential race, it is worth keeping an eye on the senate, too.

Leila de Lima, who has spent the past five years imprisoned in the national police headquarters in Manila after questioning Duterte’s drug war, is campaigning for office again.

The opposition senator is hopeful she may soon be released after two key witnesses withdrew their testimony .

De Lima was the target of vicious, misogynistic attacks by Duterte and his supporters before she was charged in 2017 with taking money from drug lords while she was justice secretary in the government of the late Benigno Aquino III .

De Lima has denied the charges and Human Rights Watch has said the case is politically motivated.

- Foreign Affairs

- CFR Education

- Newsletters

Climate Change

Global Climate Agreements: Successes and Failures

Backgrounder by Lindsay Maizland December 5, 2023 Renewing America

- Defense & Security

- Diplomacy & International Institutions

- Energy & Environment

- Human Rights

- Politics & Government

- Social Issues

Myanmar’s Troubled History

Backgrounder by Lindsay Maizland January 31, 2022

- Europe & Eurasia

- Global Commons

- Middle East & North Africa

- Sub-Saharan Africa

How New Tobacco Control Laws Could Help Close the Racial Gap on U.S. Cancer

Interactive by Olivia Angelino, Thomas J. Bollyky , Elle Ruggiero and Isabella Turilli February 1, 2023 Global Health Program

- Backgrounders

- Special Projects

United States

Book by Max Boot September 10, 2024

- Centers & Programs

- Books & Reports

- Independent Task Force Program

- Fellowships

Oil and Petroleum Products

Academic Webinar: The Geopolitics of Oil

Webinar with Carolyn Kissane and Irina A. Faskianos April 12, 2023

- Students and Educators

- State & Local Officials

- Religion Leaders

- Local Journalists

NATO's Future: Enlarged and More European?

Virtual Event with Emma M. Ashford, Michael R. Carpenter, Camille Grand, Thomas Wright, Liana Fix and Charles A. Kupchan June 25, 2024 Europe Program

- Lectureship Series

- Webinars & Conference Calls

- Member Login

The Philippines Election: A Critical Moment for Philippine Democracy

The Philippines’ upcoming presidential election is likely to bring to power the son of the country’s longtime dictator and may end Philippine democracy.

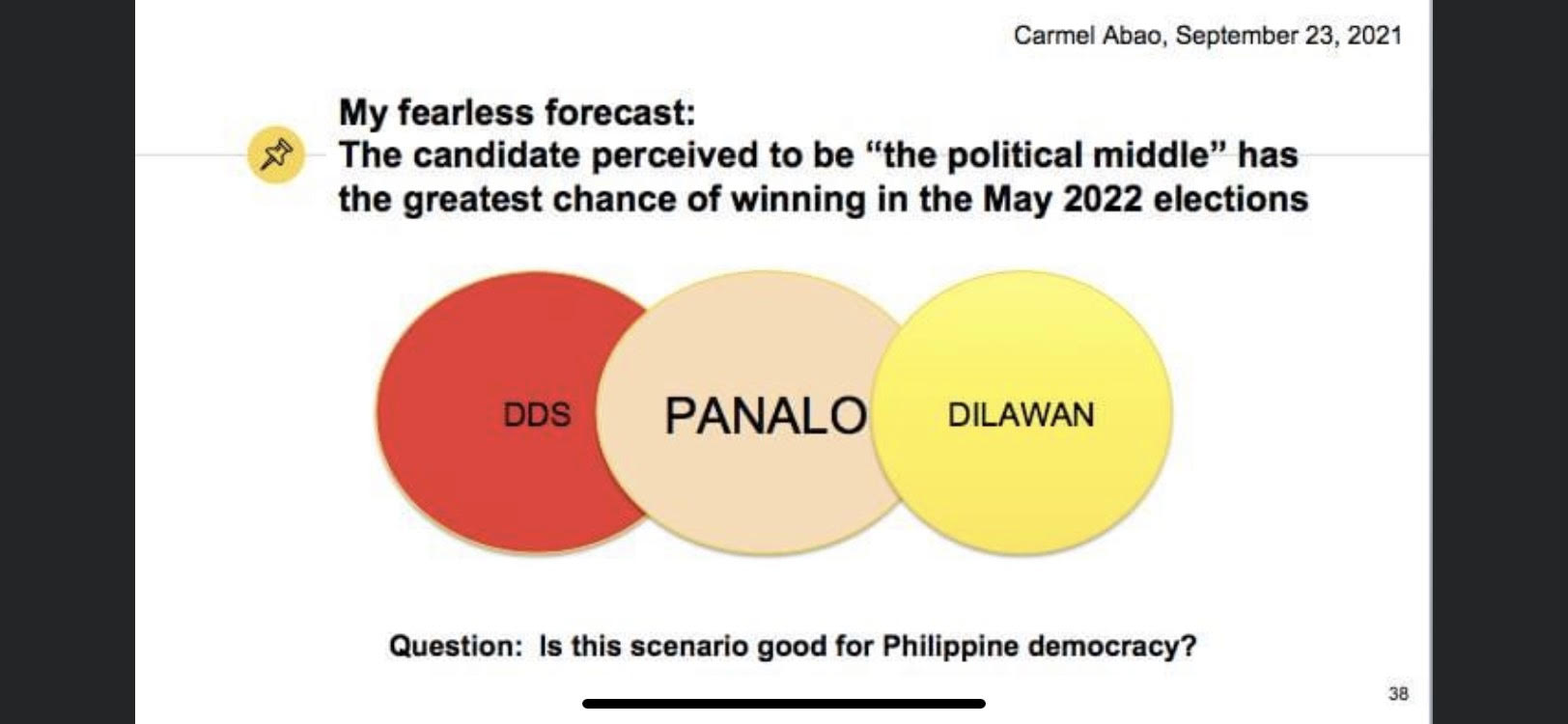

Philippine voters will go to the polls May 9 to pick their next president, who serves one, six-year term. Although there are many candidates, only two have any chance. Ferdinand Marcos Jr., son of the former longtime Philippine dictator, has a massive lead in the polls. He currently is polling at 56 percent , with the next highest candidate, former vice president Leni Robredo, polling at 24 percent . There are several minor candidates polling in the low digits. In the Philippines’ one-round system, a candidate does not even need to win a majority to be elected president. This system further favors Marcos Jr.: even if his polling numbers were to slide further, he would still be an overwhelming favorite to win in a plurality.

Southeast Asia

Philippines

Elections and Voting

For more on the Philippine election, and the implications for Philippine democracy and foreign policy, see my new CFR In Brief at: https://www.cfr.org/in-brief/philippines-election-ferdinand-marcos-leni… ;

Explore More

Vietnam caught between the u.s. and russia on ukraine, myanmar’s junta is losing the civil war.

Backgrounder

Foreign Policy at the U.S. National Political Conventions

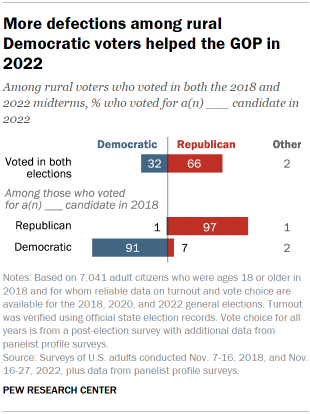

8 questions the 2022 midterms answered

There are still plenty of uncalled elections, but here are some lessons the midterms delivered.

by Christian Paz

The 2022 midterms are not yet settled. Votes are still being tallied in a score of Western contests, including close statewide races in Arizona and Nevada, and a run-off election for Georgia’s Senate seat awaits.

What questions do you have about the state of the Democratic Party?

Vox senior politics reporter Christian Paz is here to help you unpack the fractured American political system and how it affects your life. Submit your question here .

But voters delivered plenty of lessons already, including answers to some of the big questions we considered last week . Among the answers are some unique takeaways from this particular election cycle, like the effects of President Joe Biden and former President Donald Trump on their parties’ candidates, or the drag that high inflation and economic malaise would have on Democrats. We also got some clues about American politics in the longer term, like the role of candidate quality, the accuracy of polls, and changing trends among Latino voters.

Here’s what we can say about the eight questions the midterms were supposed to answer.

1) It was about more than the economy

Inflation, and the state of the economy, were still the top issues cited by most voters this year, according to early exit poll data . That data, from the National Election Pool gathered by Edison Research, is imperfect, but still the best tool we have right now to gauge voter motivations. While 31 percent of respondents cited inflation, abortion came in at a close second, being the top issue for 27 percent of respondents. Voters’ feelings about the economy were mixed: while an overwhelming majority of people said they felt the state of the economy was “not so good” or “poor” (about 76 percent), a slight majority said they felt that the personal state of their finances was better or about the same (19 and 33 percent, respectively).

Even more surprising was how voters described the impact of inflation on their families: 20 percent said inflation was a severe hardship (this group broke 70-20 for Republicans), while nearly 80 percent said it was a moderate hardship, or no hardship at all (Democrats won or broke even with these voters). That suggests that even with near-record high inflation, voters were willing to consider other factors in their voting decisions — and not everyone cared to connect the economy to their vote for a Democrat, or against a Republican.

2) An unpopular president didn’t sink Democrats

One of the more surprising results from this week was how much voters were willing to disentangle their displeasure with President Joe Biden’s job performance from their vote. The obvious absence of a red wave shows this, but just under the surface, more clues emerge. Few incumbents (in general, but more surprisingly for Democrats) lost their congressional races Tuesday night. And though three-quarters of respondents in exit polling said they felt negatively about the country’s direction, only a third were actively “angry.” Nearly 60 percent of those polled said they were either “dissatisfied, but not angry” (41 percent) or “satisfied, but not enthusiastic” (20 percent). Democrats won large majorities of those enthusiastic or satisfied, but managed to pull nearly even with those dissatisfied.

Even more impressive was the breakdown of vote share when looking at those who approve or disapprove of the president’s job performance: Democrats won huge majorities of those who strongly or somewhat approved of Biden, and nearly won a majority of those who “somewhat disapprove.” Republicans’ strength came, logically, from those who strongly disapproved of the president. But given how close so many races are, it seems that those who somewhat disapproved of Biden and national Democrats were still willing to vote for that party. Which leads us to…

3) Donald Trump was a big drag

Many candidates supported by Donald Trump fared poorly this week, and those running far-right campaigns were also punished in battleground states. This dynamic is despite the appearance of an electorate made up of more Republicans and independents than Democrats, according to exit polls. At the same time, Republicans are leading Democrats in their share of the national popular vote — meaning Trumpy candidates who failed to win did so in the context of greater Republican turnout.

Another interesting national result: Trump-endorsed candidates also underperformed more establishment candidates in swing and solid Republican states. In Nevada, for example, GOP Senate candidate Adam Laxalt was running about 7,000 votes behind Joe Lombardo, the GOP gubernatorial candidate, when their races were called. Laxalt lost and Lombardo won; despite both being endorsed by Trump, Laxalt ran a campaign more closely tied to Trump’s legacy than Lombardo.

In Georgia, Republican senatorial candidate Herschel Walker was running 203,000 votes behind Gov. Brian Kemp, one of Trump’s perceived main antagonists in the aftermath of the 2020 election, whom Trump tried to oust in the primary this year. In Ohio, J.D. Vance, the Trump-endorsed venture capitalist who won his Senate race, still underperformed (getting about 380,000 fewer votes) relative to Republican Gov. Mike DeWine, who cruised to victory by double-digit margins.

Now a power struggle has taken hold at the heart of the Republican Party, with Trump facing blame from conservative activists, media figures, members of Congress, and failed candidates. That debate has, for now, elevated the 2024 presidential prospects of Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis.

4) Abortion was a big motivator

Abortion rights did turn out to be a powerful political motivator, just as some Democrats had hoped it would be for their base, and for independent voters in states where abortion rights were on the ballot.

Ballot measures on abortion rights ended up breaking in favor of abortion rights advocates in California, Kentucky, Montana, Michigan, and Vermont , while Democratic candidates won governors’ offices in a score of states where they can block anti-abortion legislation. Pro-abortion rights Democrats also won seats in state legislatures where Republicans have tried to pass restrictions, and though Republicans held a majority in Nebraska’s legislature , state Republicans look unlikely to win a supermajority they could use to pass extreme abortion restrictions, giving moderates and liberals a way to obstruct those efforts .

The power of abortion rights messaging might offer a road map for future Democratic campaigns seeking to motivate their base and persuade moderates and independents — and Tuesday’s results showed that even if pro-abortion rights Democratic candidates don’t win elections, abortion rights on the ballot definitely can.

5) The polls were pretty accurate

The shocking lack of a red wave led some commentators to suggest that the polls this cycle were wildly off. Ask a pollster or forecaster, and they’ll likely reject that characterization.

Statewide and national polls were generally accurate — not perfect, but still clear enough to communicate just how uncertain the results might end up being. In fact, places like FiveThirtyEight, the Economist, and Cook Political Report all had a wide range of possibilities, from a red wave in the House and Senate, to a tiny majority in the House for either party and a toss-up in the Senate. Over at the Economist, G. Elliott Morris cast doubts on a red wave before the election night: “The Democratic Party … is likely to beat those expectations [of even an average midterm penalty],” he wrote . “Even a good performance by historical standards may leave the Democrats out of power in Congress.”

At the moment, it seems more likely than not that Democrats will lose control of at least one house of Congress. But traditional polling seems to have captured that uncertainty, and Morris dives into some of the reasons for that in a post here . In general, it seems like larger university and media-sponsored polls did better than partisan polls and polls conducted by smaller firms, especially in states that Democrats ended up winning .

6) Candidates mattered big time

One of the biggest lessons from 2022 is that candidate quality still matters , and as I’d written could be very possible this year, split-ticket voting had a grand return . Most Trump-endorsed candidates and MAGA true believers severely underperformed other Republicans on the ballot because of political inexperience, personal scandal, and lack of charisma, like Blake Masters in Arizona, Mehmet Oz in Pennsylvania, and Don Bolduc in New Hampshire.

Evidence of candidate quality’s importance is plentiful in both states that elected governors and senators from different parties, in states that still elected two Republicans to statewide office, and in states that have yet to be fully called. Arizona, Georgia, Nevada, and Ohio are great examples of where more conventional or charismatic Republican candidates for governor ran way ahead of flawed Senate candidates. That split was biggest in Ohio and New Hampshire, where incumbent Republican governors ran more than 20 points ahead of the Republican Senate candidates.

The phenomenon was driven by big ticket-splitting from Republican voters, and Democrats performing surprisingly well with independent voters across the country in state exit polls.

7) Latino voters might have shifted right — some places

Luckily, I do a whole deep dive on this topic here . In general, with the not totally reliable exit poll data we have, it seems like Latino voters did shift slightly to the right, though not everywhere. Florida is the large outlier, but Democrats managed to hold the bulk of their support during one of the most toxic economic environments possible — and that’s with Latino voters saying that they had strongly negative views of the economy and were dissatisfied with the country’s direction.

8) Voters did care about the threats to democracy

Trump-aligned election deniers failed across the country, especially in secretary of state races, where America First Secretary of State Coalition-aligned candidates failed in all but one race (Indiana), while another, gubernatorial candidate, Kari Lake, is still locked in a tight vote count.

In the contentious elections in Arizona and Nevada, two crucial swing states that will be at the center of the presidency and Senate control in 2024, Democratic candidates beat their election-denying Republican opponents by large margins — in some cases running ahead of other Democratic candidates in marquee statewide races. That includes the two candidates I flagged ahead of Election Day as potentially surprising the country by winning by bigger margins against right-wing opponents than Democrats in other statewide races: Cisco Aguilar in Nevada and Adrian Fontes in Arizona .

- Donald Trump

- Health Care

- Midterm Elections 2022

More in The 2022 midterm elections, explained

Most Popular

- Trump’s health care plan exposes the truth about his “populism”

- The Supreme Court is about to decide whether to interfere in the election again

- Sign up for Vox’s daily newsletter

- Is my dentist scamming me?

- What happened to Nate Silver

Today, Explained

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

This is the title for the native ad

More in Politics

The Republican ticket is taking on Big Cancer Patient.

Republicans want the Court to place the Green Party back on Nevada’s ballot after it was removed.

It’s a dangerous escalation in the conflict between Hezbollah and Israel as the war in Gaza rages on.

Trump says nasty things about immigrants all the time. But these ones have disturbingly specific Nazi parallels.

It’s a case that could have big implications for the future of Fox News.

Gisèle Pelicot’s husband drugged and assaulted her for a decade. She demanded a public trial.

Along with Stanford news and stories, show me:

- Student information

- Faculty/Staff information

We want to provide announcements, events, leadership messages and resources that are relevant to you. Your selection is stored in a browser cookie which you can remove at any time using “Clear all personalization” below.

While votes from the U.S. midterm elections are still being counted and the full results of various state races are not entirely certain, what is clear is Americans did not succumb to paranoia or violence as feared, say Stanford researchers.

According to some scholars, the election felt almost like a return to normalcy: The most vocal election deniers lost, candidates running on extreme platforms failed to resonate with voters, and even polling – which has been off in previous years – fell reasonably within the margins of error. In an election where democracy was on the ballot, it proved to be one that was largely free, fair, and trustworthy.

Here, Stanford scholars – with expertise in democracy, politics, election administration, voting, polling, and surveying American attitudes – reflect on how the 2022 election has unfolded thus far, offering their explanations on outcomes ranging from the anticipated red wave that was more of a trickle, Democrats faring better than expected, and the limited role that disinformation appeared to play in this election compared to 2020. They also share what initial results might signal about 2024, when the next general election will take place. Scholars include:

- Bruce Cain , professor of political science in the Stanford School of Humanities and Sciences (H&S), and director of the Bill Lane Center for the American West

- Emilee Chapman , assistant professor of political science in H&S

- Didi Kuo , associate director for research and senior research scholar at the Center on Democracy, Development, and the Rule of Law in the Freeman Spogli School of International Studies

- Nate Persily , the James B. McClatchy Professor of Law at Stanford Law School and co-director of the Cyber Policy Center

- Robb Willer , professor of sociology in H&S

Some answers have been edited for length and clarity.

What one word would you use to describe the midterm elections so far, and why?

Bruce Cain (Image credit: Courtesy Bruce Cain)

Cain: Relief … This was a gut check on American sanity, and fortunately, we passed (although not with honors). There was just enough recognition that the country cannot surrender to paranoia and violence.

Chapman: Complicated. Maybe the only clear narrative about the midterms is that there is no clear narrative. So far, a lot of the analysis has focused on what didn’t happen: the Republican wave that didn’t materialize. But there is no clear story about what did happen.

Persily: Surprising. I don’t think anyone predicted the particular mix of races that were won and lost. It’s quite rare that you would see such idiosyncratic results throughout the country, especially at a time when the president is so unpopular and the economy is in such a fragile state. One would have thought that there either would have been a wave election, but that would be a consistent story around the country. But instead what we see are pockets of Republican dominance and pockets of Democratic victories. Republicans have done really well in Florida and New York. Democrats have done really well in the Midwest and rust belt, except for Ohio, and then the Southwest is extremely competitive.

Is there anything you have been surprised by?

Cain: The outcome in California’s Congressional District 22 was heartening in that David Valadao, who had the courage to defy Trump and vote for his impeachment, was able to get reelected in a Republican seat. We need to have a responsible two-party system with a conservative party we can trust to uphold the values of democracy. I was also surprised at the margin of the no vote on Prop 30 [a ballot measure that proposed a tax to support the purchase of electric vehicles], but people seemed to appreciate that it may not be a good thing to let Uber and Lyft executives determine the state’s budget appropriations.

Emilee Chapman (Image credit: Courtesy Emilee Chapman)

Chapman : I wouldn’t say I’m surprised (there was a lot of uncertainty around this election), but many of the most serious worries about what this election might mean for American democracy have not come to pass. Because of recent threats against election workers and election denialism, there had been concerns about the possibility of widespread violence and disruption on Election Day, but that didn’t happen. The localized issues that arose on the day seem pretty consistent with a typical election.

Another concern going into this election was the possibility that a Republican wave would place a number of election deniers in a position to oversee elections or overturn results in key swing states. The worst-case scenario also failed to materialize here, though I am watching a few close and important races in Nevada and Arizona.

Willer: The midterm results are surprising from a fundamentals perspective. There is a tendency for the party that holds the presidency to lose Congressional seats in the midterms. Further, widespread concerns about inflation also would be expected to hurt the party that controls the presidency and Congress. Finally, Biden is relatively unpopular right now, at a level that historically would foreshadow major midterm losses. And while Dems likely will lose ground in the House, and could still lose control of the Senate as well, it was a much smaller outcome than I expected.

What explains the anticipated Republican red wave being more of a “trickle”?

Robb Willer (Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

Willer: Well, one possibility is that Trump’s unpopularity and ongoing efforts to subvert democracy are hurting Republicans. You can see evidence for this in the poor performance of several Trump-backed candidates.

Another possibility is that Republicans ran many very low-quality candidates with little political experience, like Mehmet Oz, Herschel Walker, and others. This is also related to Trump’s ongoing influence over the party, as many of these low-quality candidates gained nominations in part through Trump endorsements. Additionally, Republican voters’ willingness to vote in primaries for candidates with little or no political experience is likely related to the legacy of Trump’s presidency.

But it’s very hard to disentangle the possible negative effect of being associated with Trump from the possible negative effect associated with low candidate quality. An example would be Republican Senate candidate Hershel Walker performing worse than Republican gubernatorial candidate Brian Kemp in Georgia. Is that difference because Walker is more aligned with Trump than Kemp, and some people were turned off by that? Or is it because of the many ways in which Walker is a historically bad candidate? Or is it something else entirely, like Kemp being an incumbent? It’s very difficult to disentangle these things, especially because Trump tended to endorse lower-quality candidates.

And, importantly, we also see examples of Trump-backed candidates – like JD Vance in Ohio – performing well – so I don’t think there’s a clear, nationwide repudiation of Trump and Trumpism here.

Are there any issues you are closely following?

Cain: The fact that the surveys got this right for the most part given that so many of the races were within the margin of polling error. But more importantly, we will see whether the attacks on the legitimacy of American elections abate or simply careen further into endless litigation and factual fantasies.

Chapman: I am, of course, most closely following the state-level races that will shape the impact of election deniers in 2024.

I am also following two other things with curiosity: One is ranked choice voting. Alaska recently adopted instant runoff (a form of ranked choice voting) for statewide elections, and its significance will probably be felt in this election. Ranked choice voting was also on the ballot in Nevada, and the “yes” vote appears to be leading.

The other thing I am watching is how people used early and mail-in voting. 2020 marked a substantial shift from previous elections, both because these forms of convenience voting were much more widely used, and because there was a strong partisan divergence. Democrats in 2020 were far more likely to vote early and/or by mail than Republicans. I am watching to see whether and to what extent these two patterns remain. It seems likely that the widespread use of convenience voting is the new normal, but I am worried about the polarization of the voting method. If Democrats and Republicans predictably vote using a different method, this might make people more receptive to attempts to delegitimize the method of voting predominantly used by the other side. Polarization of voting methods may also make partisan-motivated manipulation of election administration even more attractive if it is easier to identify methods on which opponents disproportionately rely.

Persily: I was mostly concerned about the administration of the election given that there are such heightened concerns about fraud and integrity, as well as voter suppression. I wanted to see whether any of those fears would be realized and thus far they have not been, but it’s still early. I think it does depend on what happens in Arizona and in the Georgia runoff to see whether we have some of the disorder that a lot of people were worried about. To be sure, there were some malfunctions in Arizona’s Maricopa County that then led to conspiracy theories being propagated both by one of the candidates and the former president. But as a general rule, this was a very smoothly run election. And election officials deserve to be congratulated for it.

What role has disinformation played in this election?

Nathaniel Persily (Image credit: Courtesy Nathaniel Persily)

Persily: We continue to be concerned about our monitoring of false narratives that are spreading online as well as potential threats to violence and other illegal behavior. The Stanford Internet Observatory has led the Election Integrity Partnership and has been investigating false claims about the election process and so they had a very busy day [on election day, Nov. 8]. It should be no surprise that Arizona, given the concerns about the machines in Maricopa County, was seen as quite an important producer of disinformation and conspiracy theories. When/if the Senate comes down to Georgia, we should expect a lot of these conspiracy theories to be revived. That’s especially true if Kari Lake wins Arizona but right now, it doesn’t seem like we have massive conspiracy theories akin to what we saw in the 2020 election.

Why do you think that is?

Persily: In part because it’s not a presidential election, which means that Donald Trump doesn’t have exactly the same megaphone that he had back then and he can’t be as formidable a player. Also, I think because there’s no systematic story you can tell around the country. There’s no man behind the curtain who is pulling all the levers that, on the one hand, would lead to Republican dominance in Florida and in most of New York, and on the other hand, Democrats being successful in the Midwest. We’ll see in individual races like in the Georgia runoff and in Arizona and maybe Nevada but there’s no theme of election rigging that could stick to the facts on the ground they developed on Nov. 8.

Is there anything about the 2022 election that makes it unique from other elections, midterms, or otherwise?

Cain: Normally, the first midterm of a presidency is all about the incumbent president. It was indeed about Biden, but it was also about Trump. The DeSantis victory and Trump’s, at best, mixed record of candidate endorsements raise the odds that Trump will have a serious challenge to getting the 2024 Republican Presidential nomination.

Didi Kuo (Image credit: Courtesy Center on Democracy, Development, and the Rule of Law)

Kuo: President Trump loomed large over these midterm elections, and in some ways, the midterms were as much about the former president’s influence on Republican candidates as they were about Joe Biden’s first two years in office. The Big Lie, Trump’s false claim that the 2020 election was stolen, became an election issue, particularly in state elections. Some Republican candidates, particularly those endorsed by Trump, either denied the 2020 election results or refused to acknowledge whether or not the election was fair. President Trump is considering running for reelection in 2024, so it’s not surprising that a lot of attention was devoted to MAGA candidates in these elections.

Persily: This is the first election in the post-insurrection environment. And at a time when you had a collapse of confidence on the Republican side, with respect to the election infrastructure, there was a lot of anxiety coming into the administration of this election. Elected officials were facing unprecedented challenges, including threats to their safety and the safety of their families. I think there was justifiable concern about potential violence in the polls, but that did not materialize.

What lessons are we learning from the 2022 election that could potentially impact 2024?

Cain: We have learned once again that the country is divided into three camps – Democrats, Republicans, and Independents. The Democrats achieved quite a bit in the first two years just as Obama did with the Affordable Care Act. We are likely headed back to a divided government and a fight over the debt limit. Obama was able to navigate the 2011-2012 period well enough to get reelected. Can Biden do the same? If Trump is the nominee, the election comes down to the Electoral College, not the popular vote. If DeSantis is the likely nominee, will Biden be the best person for that contest? TBD, I think.

Kuo: I think there are promising signs of politics as usual. Joe Biden has been able to pass COVID stimulus bills, the Inflation Reduction Act, and industrial policy. Despite bad economic conditions, his party did well considering that presidents typically lose seats in the first midterms after they take office; the Biden agenda seems to be resonating with voters. As of this writing, we don’t know which party will control either chamber: if Republicans have a slim majority, they will likely block Biden’s remaining agenda. However, the Republican party continues to be divided between its establishment wing and its MAGA faction, and that division will likely play out in the Republican presidential race. The midterms seem to be showing that the Republican party needs to work harder to persuade voters, and that the MAGA message may not resonate.

Persily: The fact that many of the most vocal election deniers lost was a significant development in this election. It possibly signals a retreat to normalcy in part since the 2020 election. I think that the more false claims of vote rigging are defeated, the better it is for American democracy. I think those concerns still resonate with tens of millions of Americans, and many of them are going to hold elected office, so they’re not going away anytime soon. But I think that it’s quite an important signal from this election. Many people said that democracy was on the ballot in this election. And they were right because the very basic question as to whether we could continue to run elections that were free, fair, and trustworthy was an open question coming into this election, and I think that the professional running of this election suggested that we could.

Lessons from the 2022 Primaries — what do they tell us about America’s political parties and the midterm elections?

Subscribe to governance weekly, part iii - issues mentioned, elaine kamarck elaine kamarck founding director - center for effective public management , senior fellow - governance studies.

September 21, 2022

The author would like to thank research analyst Andy Cerda, for his contributions to the Primaries Project .

This is the third in a series of blog posts detailing our research on all 2360 candidates who ran for House or Senate in the 2022 primaries. We started coding each candidate by looking at their official website and then we looked at their Facebook page, their tweets, their press interviews, and their votes (in the case of incumbents) in order to determine their stances on the issues of the day. As would be expected in a primary season that ran six months, from March 1 to September 13 the salience of issues changed somewhat over time—nonetheless we managed to get a good sense of what the two parties’ candidates were talking about and perhaps, as important, what they were not talking about. We were also able to get a good sense of the divisions between the parties and within the parties.

The most talked about issues

Congressional primaries are one of the purest ways to see just how different the two parties are. Of the issues mentioned by each party only abortion and guns fell into the top five for both parties. Democrats also talked about health care, climate change and electoral integrity, while Republicans talked about immigration, taxes and regulation and inflation.

Some issues in politics are litmus tests for the parties. In 2022 there were a few issues that met this standard. For example, abortion and gun control were issues discussed by a majority of candidates in both parties. But almost no Democrats (13 out of 962) took pro-life positions and almost no Republicans—(17 out of 1398)—promoted pro-choice positions. On gun control we see a similar split, only 15 Democrats ran as strong supporters of the right to bear arms and the Second Amendment and only 30 Republicans ran as supporters of stronger gun laws.

The issue of election integrity was new to the 2020 congressional primaries, due almost entirely to Donald Trump’s continued insistence that the 2020 elections were fatally flawed, and it too became a litmus test for each party. Nearly every Democrat who mentioned reform of elections insisted that reforms were needed to make it easier to vote; while nearly every Republican who mentioned the issue talked about reforms being needed to make it more difficult to cheat.

Yet, many issues in this primary cycle were not litmus test issues. Instead, they were talked about widely by one party, but not the other. For Democrats, healthcare remained the top issue, as it was in 2018 when soon-to-be Speaker Nancy Pelosi credited health care with restoring the Democratic majority in the House. Twenty-six percent of Democratic candidates advocated Medicare-for-all or some sort of single payer system while the remaining candidates (36%) favored some form of expanding, reforming, or protecting the current health system including the Affordable Care Act (ACA). Most Republicans, 77%, simply stayed away from the issue but a minority of those who did mention it (9%) persisted in advocating repeal of the ACA.

Climate change was also high on the agenda of Democratic candidates but practically absent from the agendas of Republican candidates. Of the Republicans who did discuss climate change, (15%) took the extreme position that climate change is a hoax. Of the remaining Republicans who mentioned it, most expressed concern for what dealing with climate change might do to the economy.

Immigration was mentioned much more often by Republican candidates than by Democratic candidates. The Republican candidates who talked about immigration were evenly split. About half wanted to build the wall or finish the wall and wanted immigrants arrested and deported. The other half said, more generally, that they wanted to secure the border. Most of the Democrats who talked about immigration favored some form of comprehensive immigration reform. Very few (11 or 1%) Democratic candidates favored open borders—a further indication that the Democratic Party is nowhere near as radical as their opponents would like them to be.

Consistent with our findings in previous years, Republicans spent much more time discussing taxes and regulations than did the Democrats. This issue, of course, is an oldie but goodie, dividing the two parties well before Trump’s time. Nearly every Republican candidate who mentioned this issue said, in one way or the other, that lowering taxes and getting rid of useless regulations was the best way to help the economy. Most Democrats didn’t mention the issue, but of those who did, nearly all (94%) thought that the rich needed to pay their fair share of taxes and/or that the government should protect citizens from corporations through regulation.

The other major economic issue in 2022 was inflation. Not surprisingly, given President Biden’s vulnerability on this issue throughout most of the primary season, only 17% of Democratic candidates said anything about inflation at all. Of those who did mention it, nearly all believed that inflation would come under control once the president’s agenda was passed.

The least talked about issues

There were a set of issues that received very little attention from candidates in either party but have managed outsized attention in traditional media and social media.

In 2022, as in previous years, there were some issues that were important in Washington, DC, but which barely registered in the primaries. Critical race theory, which seemed to come out of nowhere to impact the Virginia gubernatorial race in 2021, was largely ignored by Democrats and was criticized, directly or indirectly, by the majority of Republicans who chose to talk about it.

Content regulation has been and continues to be a hot topic in Washington as the government copes with ways to regulate large social media companies and yet 94% of Democrats and 76% of Republicans had nothing to say about it. This is often the case with important policy issues that are complex and difficult to understand. For the Republicans who did talk about it, most of them understood this issue as an attempt to limit free speech, especially conservative speech. The same holds true for the debate over whether the large social media companies are monopolies and should be broken up. The vast majority of candidates in both parties (92% of Democrats and 94% of Republicans) had nothing to say about this topic.

There were also issues which were perceived to advantage one party or another and were thus not discussed. Not surprisingly, Democrats shied away from discussing the chaotic withdrawal of U.S. troops from Afghanistan in August 2021, while the Republicans who did mention it used the issue to criticize President Biden. Republicans stayed away from discussing the high cost of prescription drugs, and from discussing Biden’s infrastructure bill—two issues popular with the public. Legalization of cannabis was largely ignored by candidates in both parties, but Democratic candidates spoke more favorably about it than did Republican candidates. And the January 6 uprising at the Capitol was ignored by more Republican candidates (83%) than by Democratic candidates (65%.)

Police and criminal justice reform were mentioned equally by both parties’ candidates—45% each. The substantive divisions, however, are predictable. Republicans talked about ‘Blue Lives Matter’ and support of law enforcement. Democrats tended to talk about the need for police reform and Black Lives Matter. In keeping with our findings on other extreme, far-left, issues, very few Democratic candidates (17 out of 962 or less than 2%) talked about defunding the police.

The primary year began as the nation’s second tough winter of Covid was ending. The country was eager to put the pandemic behind it and so were the candidates. We looked for how they felt about vaccine mandates and shutdowns. As the pandemic faded into the background, few candidates talked about it. Seventy-six percent of all candidates had nothing to say about vaccine mandates; 95% of Democrats didn’t mention it at all, but 36% of Republicans did. Of that 36%, 99% of Republicans made statements against vaccine mandates. Somewhat more candidates talked about lockdowns—mostly Republicans who were against government interference. But as the pandemic began to fade, so did its salience in the primaries.

As we discovered in previous years, congressional primaries feature two distinct sets of conversations with only a small number of issues discussed in both parties. And, as we discovered in previous years, many issues that are important in Washington don’t get discussed in congressional primaries. Obviously, incumbents have positions on most of the issues because they are forced to take votes on a wide range of areas. Other candidates, however, vary widely. Some candidates run on one or two issues. Other candidates attempt to cover the waterfront of issues—some better than others.

In these polarized times the parties are diametrically opposed on many issues and surprisingly united internally. There are a few exceptions. Among the Democrats there’s a debate still waiting to happen between single payer health care and improving the patchwork of programs in our current health care system. Among the Republicans, there is a debate still waiting to happen over building a wall or doing other, perhaps more productive, things to improve border security.

Finally, there is one surprising bit of harmony in a party system plagued by conflict. As for foreign policy and America’s role in the world, candidates in both parties expressed support for a strong American presence in the world—a welcome respite from polarization.

Related Content

Elaine Kamarck

September 8, 2022

September 7, 2022

Elaine Kamarck, Celia Shapiro

September 15, 2022

Campaigns & Elections

Governance Studies

Center for Effective Public Management

Darrell M. West

September 16, 2024

Nicol Turner Lee, Darrell M. West

Kurtis Nelson, Darrell M. West

September 12, 2024

- Top Stories

- Stock Market

- BUYING RATES

- FOREIGN INTEREST RATES

- Philippine Mutual Funds

- Leaders and Laggards

- Stock Quotes

- Stock Markets Summary

- Non-BSP Convertible Currencies

- BSP Convertible Currencies

- US Commodity futures

- Infographics

- B-Side Podcasts

- Agribusiness

- Arts & Leisure

- Special Features

- Special Reports

- BW Launchpad

Reflections on the Philippine presidential race

By Diana J. Mendoza

T he race for the presidency in the 2022 Philippine elections may be the most highly divisive and contested referendum for the highest public office in the country. It is a high-stakes and high-risk contest with intense pressures to win from both the top contenders for the office and those who support them. Focusing on the top two contenders, it is a race between stopping one seeking a path back to power and electing one seeking a great reset of powers in the government.

Instead of focusing on what challenges await the next President and the country, we focus on what we can learn from the race for the presidency.

1. Elections are not just about voting candidates into or out of of fi ce. These are not merely about the change of names and faces. Elections are about the transfer and legitimation of power. Should we take a step forward to usher in a new (or reformed) governance system or take two steps back to restore an old, tarnished, and contested rule?

2. Elections should not be about those who run for office. It is about the people who should be served — their needs, rights, interests, and demands. Don’t we all deserve a new government that helps more (or mostly) the vulnerable and the marginalized while seeking to protect all regardless of any markers of differences?

3. People cannot be restrained or constrained. Filipinos are resilient. True. But when it’s their future and their loved ones’ future at high stake, they mobilize and organize. Doesn’t the spirit of volunteerism we all witnessed renew and give new meaning to the Filipino’s “ bayanihan ,” from that of communal cooperation to collective action and accountability?

4. Conventional politics must end. Political parties cannot effectively steer the public space until genuine political party reforms are made. Shouldn’t we sustain the “people’s movements” seeking to expand the political space available and bring in the concerns of everyday life that are silenced by dominant powers operating in the society?

5. No issues are either politically or morally compelling. Politically contentious or not, all issues are and should always be both politically and morally compelling. Shouldn’t we stand up for the oppressed and unjustly persecuted and the basic sectors who are really in need? Shouldn’t we stand against the politically and morally corrupt?

6. Public service is the name but public accountability is the rule of the game. Article XI, Section 1 of the 1987 Philippine Constitution states that “Public office is a public trust … officers and employees must at all times, be accountable to the people…” Why is it so difficult to execute? Shouldn’t all those who run audit themselves first even before running?

Instead of focusing on what opportunities await the next President, we focus on the salient issues and tasks for the next President to act on. These issues and tasks echo those of the Ateneo de Manila University’s Department of Political Science published in a working paper series related to the 2022 presidential and vice-presidential elections and accessible via admupol.org.

1. Pass a Security of Tenure (SOT) law that will protect workers against abusive contractualization. The next President must certify the SOT bill as urgent and mobilize support from both the House of Representatives and the Senate. Review overseas employment and prioritize the creation of jobs locally and the organization of a task force on reintegration while sustaining protection mechanisms. Forge bilateral agreements to safeguard Filipinos abroad and create migration resource centers outside of the NCR (National Capital Region) and urban areas to assist families back home.

2. Stop the misogyny and privileging of men over women that still envelope Philippine governance and politics. Socio-economic targets should not be gender-blind. They should be speci fi c and implicit in achieving gender equality and underscore bringing people together instead of polarizing the polity as well as framed and executed with an ethic of care.

3. Declare and address a crisis in education aggravated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Provide higher funding for education where the Philippines’ current 3% budget is lower than what is required by UN standards. The next President must be able to resolve issues concerning the mismatch of the skills and talents of graduates that our education system produces and the needs of our society as well as demands of industries.

4. Develop a strong public healthcare system with strong public health infrastructure throughout the country that are able to respond to any pandemics like COVID-19, non-communicable diseases, and other-health related concerns. Toward this end, the next President must ensure the effective and efficient implementation of the Universal Health Care law, the provision of free and accessible healthcare through the National Health Insurance Program and Health Care Provider Network in provinces and cities.

5. Synergize the imperatives of the security sector and justice sector reforms with Sustainable Development Goal 16 which includes the promotion of peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, the provision of access to justice for all, and building effective, accountable institutions at all levels. There is a need to shift from a militaristic, anti-insurgency approach toward human security and a whole-of-government approach to addressing the root causes of rebellion.

6. Put inclusivity, transparency and accountability at the core of the government. Don’t we all deserve public of fi cials who do not only demonstrate excellence in public service but also maintain a culture of excellence? Under the leadership of the next President, can all agencies and instrumentalities of the government aim for a culture of excellence by meeting International Public Sector Accounting Standards and earn the Commission on Audit’s seal of approval? Can the next President direct all government agencies to an audit of its management system to meet the international standard for quality management systems? To start the process, will the next President boldly order a full disclosure policy that can promote greater transparency in public service, and hence, start combating problems of corruption and patronage politics?

In light of these salient lessons and tasks, will the next President of the Philippines draft a new history with a renewed faith in democracy? Or will the next President thrust the country and its people back to a history that will forever remain tarnished, mired, and highly contested?

Diana J. Mendoza, PhD is faculty and former chair (2017-2021) of the Department of Political Science, Ateneo de Manila University.

RELATED ARTICLES MORE FROM AUTHOR

Governance in one-person corporations

The Atimonan coal project, energy transition, and the ERC

Substantiating ‘Firsts’: Women, Peace, and Security in the Philippines

‘what is your opinion of your president’, what is oligarchy.

Read The Diplomat , Know The Asia-Pacific

- Central Asia

- Southeast Asia

- Environment

- Asia Defense

- China Power

- Crossroads Asia

- Flashpoints

- Pacific Money

- Tokyo Report

- Trans-Pacific View

- Photo Essays

- Write for Us

- Subscriptions

The Philippines in 2022: Elections, Omicron, and a Delayed Recovery

Recent features.

What Could a Harris Administration Mean for Southeast Asia?

Central Asia: Facing 5 Assertive Presidents, Germany’s Scholz Gets Rebuffed on Ukraine

Envisioning the Asia-Pacific’s Feminist Future

Normalizing Abnormalities: Life in Myanmar’s Resistance Zone

Japan’s LNG Future: Balancing Energy Security With Sustainability Commitments

Why Is South Korea’s President Yoon So Unpopular?

The Logic of China’s Careful Defense Industry Purge

The Ko Wen-je Case Points to Deeper Problems in Taiwan Politics

Anarchy in Anyar: A Messy Revolution in Myanmar’s Central Dry Zone

The Complex Legacy of Ahmad Shah Massoud

Diplomacy Beyond the Elections: How China Is Preparing for a Post-Biden America

Sri Lanka’s Presidential Manifestos: What’s Promised for Women?

Asean beat | politics | southeast asia.

The nation faces a tough year, but the upcoming presidential election heralds winds of change.

Alona Nacua, right, stands with her son as she looks at their damaged house due to Typhoon Rai in Cebu city, central Philippines on Christmas Day, Saturday, Dec. 25, 2021.

The year 2021 ended tragically for the Philippines as Typhoon Rai (known locally as Odette) battered the southern part of the country, including prime tourism destinations. Recovery had barely begun when the Omicron variant once again plunged the country into panic, in addition to triggering a new set of mobility restrictions. The year 2022 is shaping up to be a tougher year, but many Filipinos are pinning their hopes on the changes that the upcoming presidential election will bring.

The election, scheduled for May 9, will give the country a new president, vice president, 12 senators, and a new term for local officials. President Rodrigo Duterte’s term will end in June and he will have no anointed successor since the candidate of his party has already backed out of the race.

The campaign period is supposed to start in February although the Omicron surge has made this uncertain. Some are even petitioning for the election to be postponed or canceled. This is unlikely to happen, but the scope of election activities is expected to be narrowed down. This will affect the interaction of candidates and voters, which could benefit incumbent officials since they have the authority to move freely even if the election campaign has yet to start.

The Commission on Elections (Comelec) will decide on various petitions, but its most important case is whether to allow former Senator Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos, the son and namesake of the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos, to run for president despite being a convicted tax evader. Marcos is leading in most pre-election surveys, but Comelec can still disqualify him and cancel his candidacy.

Because of Bongbong’s candidacy, the Marcos legacy will be intensely debated this year. Marcos will have the opportunity to defend his father, who ruled the country for two decades by imposing Martial Law in the 1970s. He should not be complacent with his high survey numbers, because aside from rivals who will engage him throughout the election period, pro-democracy forces that challenged the dictatorship will be also actively campaigning against him.

More than the Marcos issue, the pandemic will loom large in the minds of most voters. There is a general frustration over the Duterte government’s pandemic response, which has been characterized by an overreliance on prolonged militarized lockdowns. It does not help that an ongoing Senate probe is determining the culpability of Duterte officials in the signing of anomalous health supply contracts. It will not be difficult for critics to connect the corruption scandal with the medicine shortage being experienced in various urban centers. The recent declaration of several vaccine mandates could also potentially fuel street and community protests.

But public outrage is not just directed against the new restrictions but also the failure to distribute adequate relief and assistance to displaced workers and small entrepreneurs. There is a growing number of people who have expressed exasperation over the impact of urban shutdowns imposed due to COVID-19. They are joined by education stakeholders who are reeling from one of the world’s longest school closures. The Omicron variant has further delayed the reopening of schools, which means an extension of the suffering of students and educators who are enduring unreliable internet connections for distance learning classes.

In the provinces devastated by Typhoon Rai, local residents are struggling hard to rehabilitate their communities, in addition to facing the Omicron surge. One month has passed since the deadly flooding but several towns are still without water and electricity. Thousands are still in makeshift evacuation centers.

Even if Duterte has no official candidate for president, the coming election will offer a judgement vote for his presidency. His daughter is running for vice president and his party has fielded senatorial candidates. Duterte needs to address the issues mentioned above or else risk losing public support as dissatisfaction spreads in communities hit by surging infections, hunger, and poverty levels.

The Duterte government is probably ready to roll out new programs aimed at getting the nod of voters ahead of Election Day. But public anger could manifest itself not just in polling centers but also in the streets and other civic spaces, where “people power” has led to the toppling of governments in the past.

Philippine Vice President Duterte Quits Marcos Cabinet, Solidifying Rift

By sebastian strangio.

The Options for Duterte’s Post-Presidency

By mong palatino.

How Long Will Rodrigo Duterte Remain Neutral in the Philippine Election?

Marcos Jr. Receives Electoral Endorsement From President Duterte’s Party

Arakan Army Commander-in-Chief Twan Mrat Naing on the Future of Rakhine State

By rajeev bhattacharyya.

US Air Force Deploys More Stealth Jets to Southeast Asia

By christopher woody.

Islamic Fundamentalism Raises Its Head in Post-Hasina Bangladesh

By snigdhendu bhattacharya.

Kim Jong Un Abandoned Unification. What Do North Koreans Think?

By kwangbaek lee and rose adams.

By Timon Ostermeier

By Catherine Putz

By Helen Li

By John Calabrese

2022 elections: A new milestone in Philippine history

As the IT head and technology editor of the Manila Bulletin, I have closely monitored the country's national and local elections. My interest in cybersecurity has led me to focus on the security and integrity of the polls. The Department of Information and Communications Technology Cybercrime Investigation and Coordinating Center (DICT-CICC) headed by Usec. Cesar Mancao neutralized the biggest active threat of cyber-attacks days before the elections and assured the public that the agency would do everything in its power to help secure the elections. With the success of the CICC, we have a few things now to check on the security side. Many focused their attention on the automated election system for the elections.

What I noticed was that during the early hours of voting on May 9, many media organizations, unfortunately, focused on the less than 0.2 percent of the vote-counting machines that reported issues, but the more important story is the fact that over 99 percent of the VCMs performed without any problem and led to a highly-successful national and local elections. The 168 problematic machines are just 0.15% of the 107,345 VCMs used in the 2022 elections.

Social media also picked up the seemingly critical story of a few failing VCMs. However, the more interesting story that passed unnoticed was that most machines had performed well without any issues.

In some areas where the VCMs encountered issues, voters refused to surrender their ballots to poll workers. Voters decided to stay as long as necessary until they could feed the VCM with their marked ballots. Many did not see the vital story of voters who trusted the vote-counting machine (VCM) and the automated election system (AES). I was asked on Facebook if I would surrender my accomplished ballot should my precinct's VCM encounter a problem. I said yes because I trust the AES and the public school teachers serving as poll workers.

The past, where voters went home without knowing if their vote would be counted, could have played a big role in their present behavior.

With the May 9 election successfully concluded and now part of history, it is essential to look back on how the elections of the country evolved.

Despite the media coverage amplified by diligent citizens reporting on social media on any minor issues, the AES's deployment continues to improve with each election.

Results were published online immediately after the poll precincts closed. On election night, transmission reached more than 85 percent of election returns, a remarkable feat that puts the Philippines in a league of its own.

The evolution of election administration in the country is unquestionable, no matter what key performance indicator is measured.

The successful completion of the fifth automated national election confirms that automation has drastically transformed Philippine elections to greater heights.

History would tell us that Philippine elections were tarnished with fraud and irregularities before automation. For years, the country struggled to conduct free and fair elections. Each new election cycle was marked by electoral violence, contested results, a slow vote count, and widespread distrust.

After monitoring an election in 2004, the International Foundation for Election Systems wrote: "The Philippine elections are marred by allegations of cheating and fraud. This fundamentally undermines not only the credibility of election administration but also the legitimacy of the elected institutions of the state."

The AES has improved election administration in the Philippines since it was first implemented in 2010. Faster election results and an accurate, transparent count have enabled us Filipinos to trust the elections.

This improvement is why, according to a Pulse Asia survey conducted after the previous national election, 9 in 10 voters want their future elections to be automated.

The 2010 elections marked a turning point. From that election on, the country has consistently improved all election metrics.

Amid reports of malfunctioning VCMs, the Comelec assured the public it is in complete control of the situation. It described the problems encountered with the VCMs as minor. "We'd like to assure the public that these are anticipated," said Commissioner George Garcia. "The VCMs that malfunctioned, such as those unable to read or had problems with the scanner of the machines, were already solved by our operations center, including our repair hubs," Garcia said.

Garcia further explained that it's part of the Comelec protocol. "What if our requirement to vote is that the machine needs to be there? If the VCM arrives late in the afternoon, voters would only get to vote by that time," he said in a press briefing in response to numerous social media reports of VCMs breaking down.

I also explained to my social media friends and followers that poll workers' mass feeding of ballots to VCMs should not be looked at as a means of cheating, as it is part of the Comelec contingency measures in case of a problem.

Despite some issues and security concerns, the National Citizen's Movement for Free Elections (Namfrel) said the conduct of this year's general election was smooth and peaceful so far. The election watchdog made the statement at noon Monday, based on the observation of its volunteers deployed to various voting centers around the country.

The Parish Pastoral Council for Responsible Voting (PPCRV) also stated that it did not find any irregularity in the elections. The statement was released amid questions on social media from people who doubt the integrity of data from the vote-counting machine received by the transparency media server.

Manila Bulletin columnist and resident data scientist Wilson Chua also said that based on the data from the transparency media server, everything checked out. He did not see any forms of irregularity in the elections.

The 2022 election, with results available on election night and peaceful acceptance of results by the overwhelming majority of candidates, marks a new, positive milestone in the country's history.

- Open Search Search

- Information for Information For

Gen Z, Aware of its Power, Wants to Have Impact on a Wide Range of Issues

Lead author: Ruby Belle Booth Contributors: Alberto Medina, Sara Suzuki

The 2022 midterms were the first national election in which Gen Z made up the majority of the ages 18-29 electorate—the age group CIRCLE and others define as “young voters”—and 9% of all voters . In just a few years, Gen Z will make up all of that age group. Millennials, now ages 26-41, make up the remainder of the 18-29 year old cohort and they made up 26% of the electorate in 2022. While divisions by generations can be partially arbitrary groupings—and there are important differences among members of the same generation—they provide opportunities to consider the unique environments in which youth of different ages, at different times, become active in democracy.

For Gen Z, those political, social, and economic conditions have included a global pandemic, an epidemic of school shootings, and major political shifts. Using CIRCLE’s post-election youth survey, we can hone in on some of the views and experiences of the oldest members of Gen Z, including some differences between them and the youngest Millennials. (Throughout this analysis, we use Gen Z to refer only to youth ages 18-25 in our sample, and Millennial to refer to youth ages 26-29 in our sample.) We can also shine a light on some of the challenges to engaging the youngest eligible voters, who are new to elections and are often neglected by organizations and campaigns.

Among our major findings:

- Among Gen Z respondents in our poll who didn’t register to vote, about 1 in 7 said they didn’t know how or had trouble with the application

- Among youth who did not cast a ballot in 2022, Gen Zers were more likely than Millennials to say they didn’t have time, and less likely to say they thought it didn’t matter

- Millennials are more likely to prioritize economic concerns like inflation and housing costs; Gen Z is more focused than Millennials on racism and gun violence

- Family and school can be key sources of political information for Gen Z, as well as online media and social networks like YouTube, Twitter, and TikTok

Gen Zers Less Likely to Know How to Register, Have Time to Vote

For the majority of Gen Z, this may have been the first or second national election in which they were eligible to vote; for most it was their first midterm cycle. When young people are relatively new to elections they need more information and support; unfortunately they are often less likely to get it from campaigns and organizations that focus their outreach on past or likely voters.

Our data on youth who did not participate in the 2022 midterms reflect some of those challenges.

Among young people who said they did not register to vote, 16% of Gen Zers said it was either because they did not know how or had trouble with their application . That was slightly higher than the 10% of Millennials in our sample who cited either of those two issues.

Similarly, among youth who didn’t cast a ballot—whether or not they were registered—42% of Gen Z and 30% of Millennials said they forgot or were too busy. That suggests the youngest potential voters may not have been getting reminders, information about early voting options, or other support to overcome barriers to electoral participation.

Gen Z Cares About Elections, Wants to Have an Impact

Notably, despite some stereotypes about youth apathy, Gen Zers in our survey who didn’t vote were actually less likely to say that it was because it wasn’t important to them or they did not think their vote mattered. In fact, this proved to be one of the largest differences between the two generations: among youth who didn’t vote, 40% of Millennials and 28% of Gen Z said they didn’t think it mattered .

Both young Millennials and Gen Zers believe in the importance of elections and in their own power: they report, at similar rates, that they think voting is a way to have a say about the country’s future, and that young people have the ability to effect change. Gen Zers are especially aware that their vote is a tool for impact: after “it’s my responsibility,” wanting to shape the outcome was their most cited reason for casting a ballot in 2022.

Our survey also found that Gen Zers (60%) were less likely than Millennials (67%) to say that their political beliefs are somewhat or very important to their personal identity. Given Gen Z’s concern and focus on myriad issues affecting their peers and communities, that may not suggest disinterest, but a different generational lens that is less focused on personal identity and more focused on the tangible impact youth can have.

Beyond Inflation and Abortion: Gen Z Concerned about Climate, Guns, Racism

About 2 in 5 (39%) of Gen Z respondents ranked inflation and gas prices as one of their top three issues, followed by abortion (30%), jobs (26%), and climate change (23%). Both Gen Zers and Millennials in our survey cited the same top two issues: inflation and access to reproductive healthcare. However, there were some slight generational differences in the issues young people consider their main priorities. Millennials were more likely than Gen Zers to cite economic concerns like inflation/gas prices (46% vs. 39%) and housing costs (23% vs. 17%) among their top-three issue priorities.

On the other hand, Gen Zers, many of whom developed their political consciousness and aged into the electorate during years shaped by school shootings and movements for racial justice, were slightly more likely than Millennials to say that gun violence (21% vs. 16%) and racism (18% vs. 13%) were among their top three issues. However, Gen Z is not less attentive to economic concerns across the board: inflation still ranked first among Gen Z, and jobs that pay a living wage was their third highest priority, whereas Millennials ranked climate change third.

On other major issues that were central to the 2022 election cycle, like abortion, there was no major difference between Millennials and Gen Z.

Family First, but TikTok and Twitter Vital for Gen Z

Gen Zers’ political priorities, views, and attitudes may also be influenced by where they get information about issues and elections. As our research has consistently tracked, for all youth, family is the biggest source of information, though even more so for Gen Z (59% vs. 52% for Millennials) who are more likely to still be living at home. Likewise, Gen Zers, who are more likely to still be in school, were also much more likely to report that they got information about political issues from their teachers or classmates: 21% vs. 8% On the other hand, Millennials were more likely to say they heard about politics from their neighbors or coworkers.

Other differences point to the changing media and social media landscape that is critical to understand in order to effectively reach all young people. Millennials in our survey were more likely to say they got information about issues from Facebook. Members of Gen Z were more likely than Millennials to favor Twitter, TikTok, and Instagram as sources of information.