- Essay Samples

- College Essay

- Writing Tools

- Writing guide

Creative samples from the experts

↑ Return to Essay Samples

Descriptive Essay: The Industrial Revolution and its Effects

The Industrial Revolution was a time of great age throughout the world. It represented major change from 1760 to the period 1820-1840. The movement originated in Great Britain and affected everything from industrial manufacturing processes to the daily life of the average citizen. I will discuss the Industrial Revolution and the effects it had on the world as a whole.

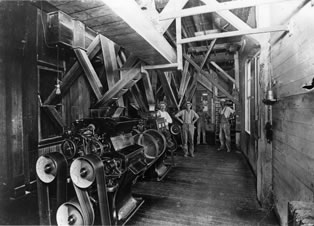

The primary industry of the time was the textiles industry. It had the most employees, output value, and invested capital. It was the first to take on new modern production methods. The transition to machine power drastically increased productivity and efficiency. This extended to iron production and chemical production.

It started in Great Britain and soon expanded into Western Europe and to the United States. The actual effects of the revolution on different sections of society differed. They manifested themselves at different times. The ‘trickle down’ effect whereby the benefits of the revolution helped the lower classes didn’t happen until towards the 1830s and 1840s. Initially, machines like the Watt Steam Engine and the Spinning Jenny only benefited the rich industrialists.

The effects on the general population, when they did come, were major. Prior to the revolution, most cotton spinning was done with a wheel in the home. These advances allowed families to increase their productivity and output. It gave them more disposable income and enabled them to facilitate the growth of a larger consumer goods market. The lower classes were able to spend. For the first time in history, the masses had a sustained growth in living standards.

Social historians noted the change in where people lived. Industrialists wanted more workers and the new technology largely confined itself to large factories in the cities. Thousands of people who lived in the countryside migrated to the cities permanently. It led to the growth of cities across the world, including London, Manchester, and Boston. The permanent shift from rural living to city living has endured to the present day.

Trade between nations increased as they often had massive surpluses of consumer goods they couldn’t sell in the domestic market. The rate of trade increased and made nations like Great Britain and the United States richer than ever before. Naturally, this translated to military power and the ability to sustain worldwide trade networks and colonies.

On the other hand, the Industrial Revolution and migration led to the mass exploitation of workers and slums. To counter this, workers formed trade unions. They fought back against employers to win rights for themselves and their families. The formation of trade unions and the collective unity of workers across industries are still existent today. It was the first time workers could make demands of their employers. It enfranchised them and gave them rights to upset the status quo and force employers to view their workers as human beings like them.

Overall, the Industrial Revolution was one of the single biggest events in human history. It launched the modern age and drove industrial technology forward at a faster rate than ever before. Even contemporary economics experts failed to predict the extent of the revolution and its effects on world history. It shows why the Industrial Revolution played such a vital role in the building of the United States of today.

Follow Us on Social Media

Get more free essays

Send via email

Most useful resources for students:.

- Free Essays Download

- Writing Tools List

- Proofreading Services

- Universities Rating

Contributors Bio

Find more useful services for students

Free plagiarism check, professional editing, online tutoring, free grammar check.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

7 Negative Effects of the Industrial Revolution

By: Patrick J. Kiger

Updated: August 9, 2023 | Original: November 9, 2021

The Industrial Revolution , which began roughly in the second half of the 1700s and stretched into the early 1800s, was a period of enormous change in Europe and America. The invention of new technologies, from mechanized looms for weaving cloth and the steam-powered locomotive to improvements in iron smelting, transformed what had been largely rural societies of farmers and craftsmen who made goods by hand. Many people moved from the countryside into fast-growing cities, where they worked in factories filled with machinery.

While the Industrial Revolution created economic growth and offered new opportunities, that progress came with significant downsides, from damage to the environment and health and safety hazards to squalid living conditions for workers and their families. Historians say that many of these problems persisted and grew in the Second Industrial Revolution , another period of rapid change that began in the late 1800s.

Here are a few of the most significant negative effects of the Industrial Revolution.

1. Horrible Living Conditions for Workers

As cities grew during the Industrial Revolution, there wasn’t enough housing for all the new inhabitants, who were jammed into squalid inner-city neighborhoods as more affluent residents fled to the suburbs. In the 1830s, Dr. William Henry Duncan, a government health official in Liverpool, England, surveyed living conditions and found that a third of the city’s population lived in cellars of houses, which had earthen floors and no ventilation or sanitation. As many as 16 people were living in a single room and sharing a single privy. The lack of clean water and gutters overflowing with sewage from basement cesspits made workers and their families vulnerable to infectious diseases such as cholera.

2. Poor Nutrition

In his 1832 study entitled “Moral and Physical Condition of the Working Classes Employed in the Cotton Manufacture in Manchester , ” physician and social reformer James Phillips Kay described the meager diet of the British industrial city’s lowly-paid laborers, who subsisted on a breakfast of tea or coffee with a little bread, and a midday meal that typically consisted of boiled potatoes, melted lard and butter, sometimes with a few pieces of fried fatty bacon mixed in. After finishing work, laborers might have some more tea, “often mingled with spirits” and a little bread, or else oatmeal and potatoes again. As a result of malnutrition, Kay wrote, workers frequently suffered from problems with their stomachs and bowels, lost weight, and had skin that was “pale, leaden-colored, or of the yellow hue.”

3. A Stressful, Unsatisfying Lifestyle

Workers who came from the countryside to the cities had to adjust to a very different rhythm of existence, with little personal autonomy. They had to arrive when the factory whistle blew, or else face being locked out and losing their pay, and even being forced to pay fines.

Once on the job, they couldn’t freely move around or catch a breather if they needed one, since that might necessitate shutting down a machine. Unlike craftsmen in rural towns, their days often consisted of having to perform repetitive tasks, and continual pressure to keep up—“faster pace, more supervision, less pride,” as Peter N. Stearns , a historian at George Mason University, explains. As Stearns describes in his 2013 book The Industrial Revolution in World History , when the workday finally was done, they didn’t have much time or energy left for any sort of recreation. To make matters worse, city officials often banned festivals and other activities that they’d once enjoyed in rural villages. Instead, workers often spent their leisure time at the neighborhood tavern, where alcohol provided an escape from the tedium of their lives.

How the Industrial Revolution Fueled the Growth of Cities

The rise of mills and factories drew an influx of people to cities—and placed new demand on urban infrastructures.

How Early World Fairs Put Industrial Revolution Progress on Display

As England and the United States transformed under the Industrial Revolution, World Fairs served to drum up support for the shift.

How Early Signs of Climate Change Date Back to the Industrial Revolution

Evidence of warming temperatures has been detected as early as the 1830s.

4. Dangerous Workplaces

Without much in the way of safety regulation, factories of the Industrial Revolution could be horrifyingly hazardous. As Peter Capuano details in his 2015 book Changing Hands: Industry, Evolution and the Reconfiguration of the Victorian Body , workers faced the constant risk of losing a hand in the machinery. A contemporary newspaper account described the grisly injuries suffered in 1830 by millworker Daniel Buckley, whose left hand was “caught and lacerated, and his fingers crushed” before his coworkers could stop the equipment. He eventually died as a result of the trauma.

Mines of the era, which supplied the coal needed to keep steam-powered machines running, had terrible accidents as well. David M. Turner’s and Daniel Blackie’s 2018 book Disability in the Industrial Revolution describes a gas explosion at a coal mine that left 36-year-old James Jackson with severe burns on his face, neck, chest, hands and arms, as well as internal injuries. He was in such awful shape that he required opium to cope with the excruciating pain. After six weeks of recuperation, remarkably, a doctor decided that he was fit to return to work, but probably with permanent scars from the ordeal.

5. Child Labor

While children worked prior to the Industrial Revolution, the rapid growth of factors created such a demand that poor youth and orphans were plucked from London’s poorhouses and housed in mill dormitories, while they worked long hours and were deprived of education. Compelled to do dangerous adult jobs, children often suffered horrifying fates.

John Brown’s expose A Memoir of Robert Blincoe, an Orphan Boy, published in 1832, describes a 10-year-old girl named Mary Richards whose apron became caught in the machinery in a textile mill. “In an instant, the poor girl was drawn by an irresistible force and dashed on the floor,” Brown wrote. “She uttered the most heart-rending shrieks.”

University of Alberta history professor Beverly Lemire sees “the exploitation of child labor in a systematic and sustained way, the use of which catalyzed industrial production,” as the worst negative effect of the Industrial Revolution.

6. Discrimination Against Women

The Industrial Revolution helped establish patterns of gender inequality in the workplace that lasted in the eras that followed. Laura L. Frader , a retired professor of history at Northeastern University and author of The Industrial Revolution: A History in Documents , notes that factory owners often paid women only half of what men got for the same work, based on the false assumption that women didn’t need to support families, and were only working for “pin money” that a husband might give them to pay for non-essential personal items.

Discrimination against and stereotyping of women workers continued into the second Industrial Revolution . “The myth that women had ‘nimble fingers’ and that they could withstand repetitive, mindless work better than men led to the displacement of men in white collar jobs such as office work, and the assignment of such jobs to women after the 1870s when the typewriter was introduced,” Frader says.

While office work was less dangerous and better paid, “it locked women into yet another category of ‘women’s work,’ from which it was hard to escape,” Frader explains.

7. Environmental Harm

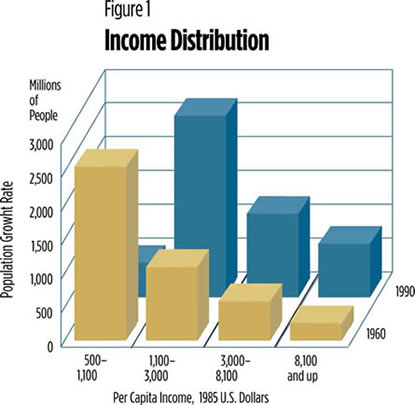

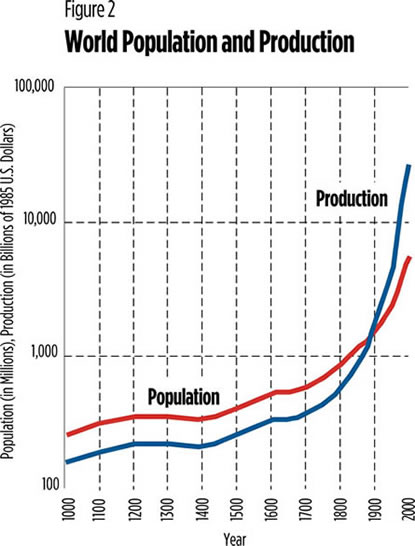

The Industrial Revolution was powered by burning coal, and big industrial cities began pumping vast quantities of pollution into the atmosphere. London’s concentration of suspended particulate matter rose dramatically between 1760 and 1830, as this chart from Our World In Data illustrates. Pollution in Manchester was so awful that writer Hugh Miller noted “the lurid gloom of the atmosphere that overhangs it,” and described “the innumerable chimneys [that] come in view, tall and dim in the dun haze, each bearing atop its own pennon of darkness.”

Air pollution continued to rise in the 1800s, causing respiratory illness and higher death rates in areas that burned more coal. Worse yet, the burning of fossil fuel pumped carbon into the atmosphere. A study published in 2016 in Nature suggests that climate change driven by human activity began as early as the 1830s.

Despite all these ills, the Industrial Revolution had positive effects, such as creating economic growth and making goods more available. It also helped lead to the rise of a prosperous middle class that grabbed some of the economic power once held by aristocrats, and led to the rise of specialized jobs in industry.

HISTORY Vault: 101 Inventions That Changed the World

Take a closer look at the inventions that have transformed our lives far beyond our homes (the steam engine), our planet (the telescope) and our wildest dreams (the internet).

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Home — Essay Samples — History — Industrial Revolution — Positive and Negative Effects of the Industrial Revolution

Positive and Negative Effects of The Industrial Revolution

- Categories: Industrial Revolution

About this sample

Words: 715 |

Published: Sep 5, 2023

Words: 715 | Pages: 2 | 4 min read

Table of contents

Positive effects: technological advancements and economic growth, negative effects: harsh working conditions and exploitation, positive effects: urbanization and social mobility, negative effects: environmental degradation, positive effects: advances in education and medicine, negative effects: social inequalities and class struggles.

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below:

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: History

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 778 words

1 pages / 526 words

4 pages / 1603 words

2 pages / 1135 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Industrial Revolution

Have you ever wondered how living organisms are able to survive and thrive in diverse environments? The answer lies in their ability to adapt. Adaptation is a crucial mechanism that allows organisms to adjust to changing [...]

The Industrial Revolution, which began in Britain in the late 18th century and quickly spread to other parts of the world, brought about significant changes in the way goods were produced, leading to a shift from agrarian-based [...]

The Industrial Revolution marked a significant period of economic, social, and technological change that transformed society in Britain during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. One of the key documents that shed light on [...]

The printing revolution, which occurred in the 15th century with the invention of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg, had a profound impact on society and the world as a whole. This technological advancement revolutionized [...]

Overview of the American Industrial Revolution as a transformative period in U.S. history Mention of the economic changes and innovations that occurred during this time Introduction to Samuel Slater as a key [...]

The Industrial Revolution in England had a profound impact on the country’s economy, society, and culture. One of the key developments during this period was the rise of textile factories, which transformed the way cloth was [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

19 Biggest Pros and Cons of Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution took place during the 18th and 19th centuries. It was a time when the predominantly rural, agrarian societies in Europe and North America began to become more urban. There was a focus on manufacturing and product development thanks to new technologies and ideas to increase efficiencies, which moved the world away from the use of hand tools in the basement to large factories in the city.

The Industrial Revolution began in the 1700s in Britain, creating a shift to special-purpose equipment that led to the mass production of items. Textiles, iron industries, and many others saw surges of improvement during this era, which contributed to better systems in the banking, communications, and transportation sectors.

When we look at the pros and cons of the Industrial Revolution, we can see that it created an increased variety and volume in the availability of manufactured goods. It is a process that helped to create an improved standard of living for some. This era also created challenging employment opportunities and living conditions for the working class.

Have we truly benefitted from the processes and technologies that came from the Industrial Revolution? Should the developing world go through this process as well?

List of the Pros of the Industrial Revolution

1. The Industrial Revolution helped goods to become more affordable. When people were making manufactured goods in their basement, most families were creating enough to meet their exact needs. If you didn’t have the skills to make your own clothes, then the scarcity in this marketplace meant that you might be spending a small fortune to get the shirt that you wanted.

Thanks to the processes introduced by the Industrial Revolution, companies could produce items faster than ever before. These methods increased the number of items that could be made per hour as well since items didn’t need to be made by hand any more. As supplies went up, then prices went down. Having an enhanced quality of life was no longer as expensive as it used to ne.

2. It helped to create the import and export markets around the world. Businesses could use the ideas created from the Industrial Revolution to have a greater supply available for specific products. When domestic demand was not enough to help maximize production, the rise of the multinational firm began. Countries could expand their import and export markets for the goods that were being made. The world began to see that the balance of trade was shifting to the producer, increasing the wealth of businesses and adding tax revenues to society.

3. Companies were creating inventions that could save on labor and time investments. Thanks to the Industrial Revolution, there was a rapid production of useful items and hand tools. This process quickly led to the development of new vehicles and tool types that could carry more items, including people, from one place to another. We began to create roads once again that could support higher levels of traffic. The telegraph came about during this time to improve our communication processes, which eventually led to the telephone and fiber optics.

Even machines like the Spinning Jenny, which was a multiple spindle item that could spin cotton or wool, allowed us to make more things in less time. When electricity became available, then refrigeration and home appliances increased our standard of living even further.

4. It led to an evolution in our approach to medicine. Many of the advances that led to the development of modern medical practices occurred because of the efforts of the Industrial Revolution. It became possible to make more instruments, such as test tubes, scalpels, and lab equipment, at a lower cost so that more people could enter this field. Refinements to design helped doctors become more effective at what they could do.

As communication lines improved throughout the world, doctors and researchers could work together to find new cures or treatments for deadly diseases instead of trying to do everything on their own. New best practices were developed based on the findings of this work. These processes results in a significant increase of patient care throughout the world.

5. The Industrial Revolution improved the quality of life for the average person. Until the Industrial Revolution swung into action full force, it was typically the aristocratic people in society who benefitted from comfort and convenience. Thanks to mass production, lower costs, and greater availability, people in the working class could obtain more items while still having money left to save for other things. Even though there were some poor working conditions at the time, it became possible for a majority of families to start building wealth of their own.

That meant people could own a home without being a farmer. They could have enough food to get by for the week instead of limiting themselves to one meal per day. Some companies were even building towns and giving away homes to those who were willing to work in the factories. This event helped to shape our modern infrastructure.

6. It created more job opportunities around the world. As new manufacturing equipment began to make its way to factory floors, there were new jobs created in each community. There were fewer land-related concerns that drove the economy because there was less dependence on farm labor wages. It meant the average person could make their wealth with a decent job as an employee instead of trying to carve out a life for themselves on their own.

Some workers even took a portion of their wages to invest in other companies, leading to a growing middle class around the world. It created a new pool of economic power that started to limit the influence of the aristocracy. This advantage eventually led to a shift in local laws that helped to give more rights to the average person.

7. The Industrial Revolution led to the rise of specialists. The only real specialists that existed in the economy before the Industrial Revolution were the farmers and agricultural workers who grew one crop for sale. As factories began to start operating in the cities, rural families began to move to the cities because the jobs there would pay better. Owners began to train factory workers to perform specific tasks that could become their specialty.

Some workers began to transport raw materials for processing. Others worked on specific machines. There were people in maintenance, marketing, or charged with making improvements to the overall operations of each facility. As each task became more skilled, there became a need to have more trainers to pass on what had been learned.

8. It led to the modern development of municipalities. As people began to move away from the rural life to pursue their opportunities in the Industrial Revolution, governments needed to change how they supported each municipality. The bureaucracies grew to support specialized departments that could handle sanitation issues, tax collection, traffic problems, and other localized services that were necessary. New businesses began to form as people began to support these workers, leading to lawyers, physicians, and builders forming their own opportunities.

9. Anyone had the opportunity to make it big during the Industrial Revolution. Charles Goodyear is credited with the discovery of rubber vulcanization, a process that allows it to withstand heat and cold. This process revolutionized the industry in the middle of the 19th century. It was also a journey that almost ruined his life. Goodyear put his family into substantial debt to finance his rubber experiences. He moved anywhere to find investors and laboratory space.

At one point, he sold his furniture, begged for money, and even sold the textbooks of his children. After the financial panic of 1837, he lost almost everything. Then, in a miracle accident, he combined rubber and sulfur on a hot stove. It hardened when it got hotter. Many people pursued a similar path without finding the same success, but it was one of the first times in history when anyone could invest into themselves to change their stars.

10. Manufactured products were seen as an investment more than a necessity. Before the Industrial Revolution changed the quality and quantity of the goods we consume, items were purchased because of their usefulness. When inventories began to build and products became cheaper, we could make clothes that lasted longer. Structures required less maintenance. People were spending less time making their own items because a small investment created long-term results.

This advantage also increased the amount of competition that society experienced. Instead of staying in the family business or becoming an apprentice of a relative, anyone could travel anywhere in the industrialized world to look for employment opportunities that they wanted. It is a process that would help to create the first authentic free-market economies.

List of the Cons of the Industrial Revolution

1. It led to a significant amount of wealth inequality. Before the Industrial Revolution occurred, the only people who were genuinely wealthy were those who came from royalty or had invented something that was exceptionally useful to society – such as a telescope. After this development period, it was the people who were leading the businesses that made the most money – and it was often at the expense of the poor and working class.

Before his divorce proceedings in 2019, the estimated net worth of Jeff Bezos was about $157 billion. His finances, along with Mark Zuckerberg, Bill Gates, and Elon Musk are all the subject of modern wealth inequality conversations. If you look at the American Industrial Revolutionists like Andrew Carnegie and John Rockefeller, they had $310 billion and $340 billion at a time when the money was worth more.

Rockefeller by himself controlled 1.5% of the American economy. Using a standard inflation calculator, his net worth by today’s standards of value was over $8.1 trillion.

2. The Industrial Revolution led to an overcrowding in the cities. Many migrants began to make their way to the industrial towns and major cities during the Industrial Revolution because of the promise of better wages. These communities were not prepared for the influx of people that headed their way. Builders would eventually help to relieve the initial housing shortages that occurred, eventually leading to the modern building and multi-floor structures, there were lots of shantytowns that developed in the early days in Britain.

This disadvantage led to problems with sewage and sanitation, which caused contamination of the local drinking water. With lots of people all living in the same area, worn out by challenging working conditions, and consuming unsafe fluids, there were numerous disease outbreaks. Smallpox, cholera, tuberculosis, and typhus were all significant problems in the industrialized cities until urban planning and medical care could improve the environment.

3. It creates a higher level of pollution in the environment. Many of the environmental problems that we still struggle with today are because of the activities and follow-up technologies from the Industrial Revolution. Factories needed fuel to sustain their daily output, so natural resources were transformed into capital. We began to use our soil, minerals, trees, oil, and water to continue producing items. This disadvantage led to global challenges that included air pollution biodiversity reduction, water pollution, habitat destruction, and even global warming.

As more countries began to pursue wealth through this process, then the adverse ecological transformations increate. One of the drivers of this problem is carbon dioxide. Before 1750, the level of CO2 in the atmosphere was about 290 parts per million. It was 400 parts per million by volume in 2017.

4. The Industrial Revolution appropriates materials for natural use to human use. Humanity is now using about 40% of its planetary land-based net primary production to create items through manufacturing processes because of the Industrial Revolution. This measurement is the rate at which plants convert solar energy for nutrients and growth. As populations rise, more of our resources go toward human use instead of allowing nature to run its course. That means there are fewer ecosystem services, such as clean water and air, that plants and animals can use.

Our biosphere depends on these elements for our survival. Unless we are willing to make changes to our manufacturing processes that reduce the threat of habitat destruction and resource consumption, the future of our world could look very different than what we have today.

5. There were very poor working conditions in the early factories. When the Industrial Revolution began to build factories in the cities and industrial communities, the business owners looked to maximize their profit through high levels of production. Wages and worker safety were rarely an important part of that equation. Although families could earn more working in these conditions when compared to the rural life, it came through an agreement to work up to 16 hours per day, six days per week. Women and children earned half as much of the men if they were lucky.

The equipment in the factories was usually dirty as well, expelling soot and smoke that led to breathing issues, accidents, and injuries. Although this disadvantage would eventually lead to the formation of labor unions, there were a lot of family sacrifices made before this societal transformation.

6. It created a culture of passivity. The Industrial Revolution helped to develop numerous labor-saving devices and equipment. Instead of performing strenuous activities for the bare minimum of needs, people were using equipment more often. Specialized tools allowed for tilling, planting, and harvesting. Bicycles and automobiles reduced the need to walk. Tasks that used to require physical exertion became sedentary office jobs.

That led to entertainment options that became sedentary as well. Our eating choices became more about convenience than nutrition. It has led to a culture where many people eat items that are heavily processed with sugar and salt to maintain shelf life, increase sweetness, and lower cooking times. This disadvantage has led to lifestyle-related diseases like heart disease, obesity, and even some forms of cancer.

7. The Industrial Revolution was powered by petroleum and other oils. It was not petroleum that helped to initially fuel the Industrial Revolution around the world. It was whale oil. This product was useful for soap and margarine, and it was widely used in the oil lamps of the time. It was not until the 19th century, when we began to use petroleum products for these needs, that the hunting habits for these creatures began to decline. The only way to harvest that product was to boil strips of blubber after pulling the creature to land.

If it happened at sea, the oil was harvested on the ship, and then the remaining carcass was thrown into the ocean to catch the next one. This disadvantage caused a significant reduction in the population of baleen, bowhead, and right whales. They were hunted almost to extinction.

8. It changed how we produce agricultural items. The factory processes drove many workers away from the farms to earn better wages and live in bigger homes. That meant the agricultural sector had to do more with fewer workers. This disadvantage would eventually lead to the formation of corporate, large-scale forming. New methods of food production had to be created to serve the growing industrial tows around the world.

Instead of growing crops and raising livestock to meet the needs of each family, agriculture became a business that focused on profits and losses. This disadvantage is what eventually led us to the world of genetically modified foods, potentially harmful pesticides, and similar problems in our food chain.

9. The Industrial Revolution changed the politics of the world. We are still experiencing the fallout of the Industrial Revolution today. There are currently less than 40 nations who we consider to have gone through the full industrialization process. The opportunities for success are much greater there than the rest of the world in comparison. Although most people can find a way to receive an education in the developed world if they want that opportunity, the lack of resources that are available domestically make it nearly impossible for trained individuals to come home to make the changes that are necessary for success.

This creates a dependency on the developed countries because the developing world does not have the same resource access. That is why a majority of the income today is in the nations that went through the Industrial Revolution at its earliest stages.

Verdict on the Pros and Cons of the Industrial Revolution

When we look at the results of the Industrial Revolution today, many of the items that we take for granted came about because of this process. Even for population centers in the developing world, the access to affordable clothing, production tools, and leisure equipment is due to the innovation and creativity from this time.

We must also recognize that the countries who went through the Industrial Revolution are the ones which benefitted the most financially from this process. Societal wealth was built on the backs of the working class, which allowed the aristocracy to remain in power – just in a different way. Instead of controlling the entire market, those in charge helped to determine who could have access to the new economy.

The pros and cons of the Industrial Revolution are essential to review today because we are going through a new process. We are in the middle of the Data Revolution, where every action we take in person or online allows companies to develop insights into our behavior. This process creates targeted marketing mechanisms which we continue to support through our own labor while the environmental consequences begin to build.

Unless we learn from the lessons of the past, we will repeat the same mistakes in the future.

Essay on Industrial Revolution

Introduction to the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was a pivotal moment in history, radically reshaping societies, economies, and landscapes worldwide. Beginning in the late 18th century, this era of rapid technological advancement and urbanization marked a profound departure from agrarian lifestyles. For example, the mechanization of textile production in Britain revolutionized manufacturing methods, resulting in unprecedented economic growth and social change. As steam-powered factories proliferated, traditional modes of living gave way to the relentless march of progress. This essay explores the complex impact of the Industrial Revolution, analyzing its causes, consequences, and long-term influence.

Historical Context

- Pre-Industrial Society : Before the Industrial Revolution, most societies were agrarian, with most people living in rural areas and working in agriculture .

- Technological Limitations : Most manufacturing was done in small-scale workshops using hand tools, limiting production capacity and efficiency.

- Limited Transportation : The need for efficient transportation systems made moving goods and people over long distances difficult.

- Cottage Industry : Some manufacturing processes were decentralized and conducted in homes (known as the cottage industry), but there was a need to improve this on a larger scale and broader scope.

- Feudalism and Guilds : Feudal social structures and guilds controlled much of the economic and social life, restricting innovation and economic growth.

- Mercantilism : Economic policies were often based on mercantilist principles, emphasizing exporting more than importing and accumulating precious metals.

- Enlightenment Ideas : The Enlightenment brought new ideas about science, reason, and individualism, setting the stage for questioning traditional practices and systems.

Significance of the Industrial Revolution

- Economic Transformation : Agrarian economies gave way to industrialized ones during the Industrial Revolution, which resulted in unheard-of economic development and wealth creation.

- Technological Advancement : It introduced groundbreaking innovations such as the steam engine, mechanized textile production, and transportation systems, laying the foundation for modern industrial and technological progress.

- Urbanization : As factories and industrial hubs grew, many people moved from rural to urban areas, accelerating urbanization and changing the demographic picture.

- Social Change : The Industrial Revolution brought about profound social transformations, including the emergence of the working class, changes in family structures, and new patterns of consumption and leisure.

- Global Impact : Industrialization spread from its birthplace in Britain to Europe, North America, and eventually the rest of the world, reshaping global trade patterns and contributing to colonial expansion.

- Environmental Impact : While facilitating unprecedented production and consumption, industrialization also led to environmental degradation, including pollution, deforestation, and resource depletion.

- Political Ramifications : The rise of industrial capitalism challenged traditional power structures, leading to political reforms, labor movements, and the rise of new ideologies such as socialism and communism.

- Cultural Shifts : The Industrial Revolution influenced cultural production, including literature, art, and music, reflecting the social and economic changes of the era and shaping modern cultural sensibilities.

Pre-Industrial Society

- Environmental Impact : While facilitating unprecedented production and consumption, industrialization also led to environmental degradation, including pollution, deforestation , and resource depletion.

Catalysts of Change

- Technological Innovations : The development of new technologies, such as the steam engine, mechanized looms, and the spinning jenny, revolutionized production processes, increasing efficiency and output.

- Economic Factors : Changing economic conditions, including the rise of capitalism, the accumulation of capital, and the demand for cheaper and more abundant goods, created incentives for innovation and investment in industrial ventures.

- Social and Political Developments : Shifts in social structures and political systems, such as the decline of feudalism, the rise of urban centers, and changes in labor relations, provided fertile ground for the emergence of industrialization.

- Access to Resources : The availability of resources, including coal and iron ore, provided the necessary raw materials for industrial production, while access to markets facilitated the distribution and sale of goods.

- Colonial Expansion : Colonial empires gave access to new markets, raw materials, and investment opportunities, resulting in economic growth and industrial development in colonial powers.

- Scientific Advancements : Advances in science and engineering, as well as applying scientific principles to industry, fueled innovation and technological progress, accelerating the pace of change.

- Trade and Globalization : Increasing interconnectedness through trade networks and globalization facilitated the diffusion of ideas, technologies, and capital, contributing to the spread of industrialization beyond its initial development centers.

Industrialization Spreads

- Britain Leads the Way : The Industrial Revolution originated in Britain in the late 18th century, driven by abundant natural resources, a skilled workforce, and a conducive political and economic environment.

- Europe and North America : Industrialization spread rapidly to other parts of Europe, including France, Germany, and Belgium, and North America, particularly the United States and Canada, where it fueled economic growth and urbanization.

- Global Implications : The spread of industrialization had profound global implications, as European powers established colonial empires and introduced industrial technologies to colonies in Asia, Africa, and the Americas.

- Colonial Industrialization : Colonies became centers of raw material extraction and production for the industrialized world, contributing to global trade networks and economic interdependence.

- Asia and Latin America : Industrialization also took root in certain regions of Asia, such as Japan, India, and China, as well as in countries in Latin America, albeit to varying degrees and with different trajectories influenced by local conditions and historical factors.

- Impact on Global Economy : The spread of industrialization reshaped the global economy, leading to shifts in wealth and power, the emergence of new economic centers, and increased competition for resources and markets.

- Technological Diffusion : Advances in transportation and communication facilitated the diffusion of industrial technologies and knowledge, accelerating the pace of industrialization worldwide.

- Social and Cultural Changes : Industrialization brought about significant social and cultural changes in societies worldwide, including urbanization, changes in family structure, and shifts in values and lifestyles.

Impact of the Industrial Revolution on Society

Watch our Demo Courses and Videos

Valuation, Hadoop, Excel, Mobile Apps, Web Development & many more.

- Urbanization and Population Growth : The growth of factories and industrial centers caused widespread migration from rural areas to urban centers, resulting in fast urbanization and the establishment of large populations in cities.

- Social Stratification and Class Conflict : Industrialization created a new class structure, with industrial capitalists, factory owners, and managers at the top and a working class of laborers and factory workers at the bottom, leading to increased social stratification and class conflict.

- Changing Gender Roles : Industrialization reshaped traditional gender roles as women entered the workforce in large numbers, particularly in factories and mills, challenging traditional notions of women’s roles in society.

- Child Labor and Exploitation : The demand for cheap labor in factories led to the widespread exploitation of children, who were employed in hazardous working conditions and often subjected to long hours and low wages.

- Urban Poverty and Poor Living Conditions : Industrialization led to urban poverty and slums because cities struggled to provide adequate housing, sanitation, and public services for their growing populations .

- Labor Movements and Unionization : The harsh working conditions and labor exploitation in factories spurred the rise of labor movements and the formation of labor unions, which fought for better wages, working hours, and conditions for workers.

- Education and Social Reform : Industrialization led to increased emphasis on education and social reform, as reformers sought to address the social problems and inequalities caused by industrialization through initiatives such as public education, social welfare programs, and labor laws.

- Family Dynamics : Industrialization transformed family dynamics as families migrated to cities in search of work, leading to changes in family structure, roles, and relationships, as well as new challenges in balancing work and family life.

- Cultural Shifts : Industrialization brought about cultural shifts, as urbanization, mass production, and technological advancements influenced art, literature, music, and popular culture, reflecting the social and economic changes of the era.

Economic Transformation

- Rise of Capitalism : The Industrial Revolution marked the ascendance of capitalism as the dominant economic system characterized by private ownership of the means of production, profit motive, and market competition.

- Factory System and Mass Production : The development of the factory system enabled the mass production of goods on a scale never before seen, leading to increased efficiency, lower costs, and the production of a wide variety of consumer goods.

- Division of Labor : Industrialization introduced the concept of division of labor, where tasks were broken down into smaller, specialized tasks performed by different workers, increasing productivity and efficiency.

- Expansion of Markets : Industrialization expanded markets for goods, both domestically and internationally, as transportation networks improved and global trade increased, leading to economic growth and prosperity.

- Labor Exploitation and Working Conditions : While industrialization brought economic growth, it also led to labor exploitation, with long hours, low wages, and poor working conditions in factories and mines.

- Technological Advancements : Technological innovations that revolutionized production processes and communication, such as the steam engine, mechanized looms, and the telegraph, were the driving forces behind industrialization.

- Impact on Agriculture : Industrialization also profoundly impacted agriculture, with the mechanization of farming leading to increased agricultural productivity and the migration of rural populations to urban areas in search of work.

- Formation of Business Corporations : The Industrial Revolution saw the rise of large business corporations, which became dominant players in the economy, controlling vast resources and influencing government policies.

- Income Inequality : Industrialization led to income inequality, as industrial capitalists amassed wealth while many workers struggled to make ends meet, leading to social unrest and calls for reform.

Technological Advancements

- Steam Power : The invention and widespread use of the steam engine revolutionized the industry, enabling factories to be powered by steam and significantly increasing transportation efficiency through steam-powered trains and ships.

- Mechanization of Textile Production : Innovations such as the spinning jenny, water frame, and power loom mechanized textile production, leading to the rapid growth of the textile industry and the availability of cheap clothing.

- Iron and Steel Production : The advancement of new techniques for iron and steel production revolutionized construction and manufacturing, facilitating the creation of bridges, railways, and buildings on an unprecedented scale.

- Transportation Revolution : The Industrial Revolution saw the development of steam-powered locomotives and railways, significantly improving transportation efficiency and connectivity and facilitating the movement of goods and people over long distances.

- Communication Revolution : Samuel Morse’s invention of the telegraph revolutionized communication, enabling messages to be sent quickly over long distances and transforming business, government, and personal communication.

- Chemical Innovations : Advances in chemistry led to the development of new materials, such as plastics and synthetic dyes, revolutionizing manufacturing and consumer goods production.

- Machine Tools : The invention of machine tools such as lathes and milling machines revolutionized manufacturing, enabling the mass production of precision parts and components.

- Electrical Revolution : The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw the harnessing of electricity for industrial use, leading to the development of electric lighting, motors, and appliances, transforming daily life and industry.

- Medical and Scientific Advances : The Industrial Revolution also saw significant advancements in medicine and science, such as the development of vaccines, the germ theory of disease, and the understanding of electricity, laying the groundwork for future scientific and medical discoveries.

Cultural and Intellectual Shifts

- Urbanization and the Rise of Urban Culture : The migration of people from rural areas to cities led to the emergence of urban culture, characterized by new forms of entertainment, leisure activities, and social interactions in urban centers.

- Literary and Artistic Movements : The Industrial Revolution gave rise to literary and artistic movements such as Romanticism and Realism that explored the changes brought about by industrialization in themes like nature and the human condition.

- Educational Reforms : The need for an educated workforce led to educational reforms, including expanding public education and establishing schools and universities to provide workers with the skills needed for industrial jobs.

- Scientific Advancements : Significant advancements in science and technology, such as the emergence of new scientific theories like Darwin’s theory of evolution and the application of scientific principles to industry and medicine, coincided with the Industrial Revolution.

- Rise of Consumer Culture : The expansion of mass production and the accessibility of affordable consumer goods contributed to the emergence of consumer culture, with advertising and marketing assuming a central role in influencing consumer preferences and behaviors.

- Social Reform Movements : The harsh working conditions and social inequalities of the Industrial Revolution spurred the rise of social reform movements, including labor unions, women’s rights movements, and movements for social justice and equality.

- Philosophical and Political Ideologies : The Industrial Revolution gave rise to new philosophical and political ideologies, such as socialism, communism, and liberalism, which sought to address the social and economic challenges of the era and envision alternative visions of society.

- Impact on Religion : The Industrial Revolution profoundly impacted religion, challenging traditional beliefs and practices through scientific discoveries, technological advancements, and evolving social conditions.

- Cultural Exchange and Globalization : The Industrial Revolution facilitated cultural exchange and globalization, as ideas, goods, and people traveled more freely across borders, leading to the spread of cultural influences and the emergence of a more interconnected world.

Responses and Resistance

- Labor Movements and Unionization : Workers organized into labor unions to advocate for better wages, working conditions, and rights. Strikes, protests, and collective bargaining were common tactics used by labor movements to challenge the power of industrial capitalists.

- Luddite Movement : The Luddites were groups of workers who protested against introducing new machinery and technology in the textile industry, fearing that it would lead to job losses and exploitation. They engaged in acts of sabotage and destruction of machinery as a form of resistance.

- Government Regulation and Reform : In response to social and labor unrest, governments enacted labor laws and regulations to safeguard workers’ rights and enhance working conditions. These reforms included limits on working hours, safety regulations, and the establishment of minimum wage laws.

- Socialism and Communism : Socialism and communism are political ideologies advocating for collective ownership of means of production and redistribution of wealth to address social inequalities. Socialist and communist movements sought to challenge the power of industrial capitalists and create a more equitable society.

- Mutual Aid Societies : Workers formed mutual aid societies and cooperatives to provide support and assistance to each other in times of need, such as illness, injury, or unemployment. These organizations helped strengthen solidarity among workers and provide a safety net without government support.

- Religious and Ethical Responses : Religious and ethical movements, such as the Social Gospel movement, emphasized the moral imperative to address social injustices and improve the lives of the working poor. These movements often worked alongside labor unions and social reformers to advocate for social change.

- Artistic and Cultural Resistance : Artists, writers, and intellectuals employed their work to scrutinize the Industrial Revolution’s social and economic inequalities and raise awareness about the challenges faced by the working class. Literature, art, and music often depicted the struggles and hardships faced by workers in industrial society.

- International Solidarity : Workers’ movements and labor unions forged alliances and solidarity networks across national boundaries to support one another’s struggles and exchange resources and information. Global labor conferences and congresses were held to coordinate efforts and advocate for workers’ rights on an international scale.

Legacy of the Industrial Revolution

- Economic Transformation : The Industrial Revolution laid the foundation for modern industrial economies, shifting societies from agrarian to industrial and setting the stage for unprecedented economic growth and development.

- Technological Advancements : The Industrial Revolution introduced revolutionary technologies that transformed industry, transportation, and communication, leading to the modern world of machinery, factories, and global interconnectedness.

- Urbanization and Population Shifts : The Industrial Revolution spurred the expansion of cities and the emergence of urban centers as hubs for industry, commerce, and culture.

- Social and Political Changes : The Industrial Revolution brought about significant social and political changes, including the rise of capitalism, the emergence of new social classes, and the expansion of democracy and political rights.

- Environmental Impact : The Industrial Revolution had a profound impact on the environment, leading to pollution, deforestation, and other forms of environmental degradation that continue to affect the planet today.

- Labor Rights and Social Welfare : The Industrial Revolution spurred movements for labor rights and social welfare, leading to the establishment of labor laws, minimum wage regulations, and other protections for workers.

- Globalization : The Industrial Revolution was a key driver of globalization, connecting distant parts of the world through trade, transportation, and communication networks and shaping the modern global economy.

- Cultural and Intellectual Shifts : The Industrial Revolution influenced cultural and intellectual developments, leading to new artistic movements, scientific discoveries, and philosophical and political ideologies impacting society today.

- Inequality and Social Justice : The Industrial Revolution also deepened inequalities and social injustices, leading to ongoing debates and struggles over issues such as wealth distribution, labor rights, and environmental sustainability.

The Industrial Revolution is a transformative epoch in human history, reshaping societies, economies, and landscapes across the globe. Its legacy is profound, laying the foundation for modern industrialized societies and shaping the course of modernization, urbanization, and globalization. While it brought unparalleled economic growth and technological advancement, it also presented substantial social and environmental challenges, including urban poverty, environmental degradation, and labor exploitation. As we reflect on its impact, it is essential to learn from the past, striving to address its legacies of inequality and environmental damage while harnessing its innovations for a more sustainable and equitable future.

*Please provide your correct email id. Login details for this Free course will be emailed to you

By signing up, you agree to our Terms of Use and Privacy Policy .

Valuation, Hadoop, Excel, Web Development & many more.

Forgot Password?

This website or its third-party tools use cookies, which are necessary to its functioning and required to achieve the purposes illustrated in the cookie policy. By closing this banner, scrolling this page, clicking a link or continuing to browse otherwise, you agree to our Privacy Policy

Explore 1000+ varieties of Mock tests View more

Submit Next Question

Early-Bird Offer: ENROLL NOW

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

Industrial Revolution Causes and Effects

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Numismatics

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Social History

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Acquisition

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music and Religion

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Law and Politics

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Legal System - Costs and Funding

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Restitution

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Games

- Computer Security

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business Strategy

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Social Issues in Business and Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Systems

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education