The Photo That Saved the Franklin River

The power of photography, wielded wisely..

21 Apr 2017

Further reading

Burning Cold: Indigenous Fire Knowledge with Victor Steffensen

Art as “Quiet Activism” with Minna Leunig

Tide In Tide Out: A Mesmerising, Moving Meditation

In Studio: A Look Inside Joan Miró’s Workshop

The Beekeeper Using Art to Bring People Closer to Nature

- Science & Environment

- History & Culture

- Opinion & Analysis

- Destinations

- Activity Central

- Creature Features

- Earth Heroes

- Survival Guides

- Travel with AG

- Travel Articles

- About the Australian Geographic Society

- AG Society News

- Sponsorship

- Fundraising

- Australian Geographic Society Expeditions

- Sponsorship news

- Our Country Immersive Experience

- AG Nature Photographer of the Year

- View Archive

- Web Stories

- Adventure Instagram

Home Topics Science & Environment Bob Brown reflects on saving the Franklin River

Bob Brown reflects on saving the Franklin River

WHO REALLY THINKS, given the greed and short-sightedness evident in human history, that this crowded populace will not invade, occupy and exploit the remainder?

Some say there is no pure wilderness left. Everywhere – no matter how remote – is contaminated with chemicals, heated by climate change or invaded by weeds and feral animals. The beauty of the night sky is blotted out by the glow of the cities and criss-crossed by the twinkling lights of jetliners and other objects, such as the space station, which appears brighter than Venus.

As if to hasten the end of wilderness, state governments in New South Wales, Victoria, Western Australia and Queensland have recently agreed to open national parks to cattle grazing, recreational shooting (see page 36) and off-road motor vehicles, which will cause all manner of impacts. What is more, “sustainable” mining, logging and private-enterprise tourism businesses are on the drawing boards for some of Australia’s most far-flung and exquisitely beautiful places.

When I first floated down Tasmania’s wild Franklin River with Launceston forester Paul Smith in 1976, this was all on the way. Although the immediate threat to the Franklin was the contested Gordon-below-Franklin Dam, our talk around the campfire was about the loss of the remote and pristine nature of the landscape, qualities of truly wild country already missing in some parts of Tasmania.

Loss of pristine Tasmania forest

The devastating impact of the road from Maydena to Strathgordon was already evident. It was built in the middle of Tasmania’s southwest wilderness more than a decade earlier – funded by a £5 million (about $120 million today) grant from the Commonwealth under prime minister Robert Menzies.

The road increased access to Lake Pedder National Park, which was established in 1955 and folded into Southwest NP in 1968 before the construction of three dams for generating hydro-electricity flooded the lake itself. Once-fabled bushwalking destinations, including Frankland Range, Mt Anne and even the Western Arthurs, lost their character as the huge expanse of the flooding lake and its attendant white gravel roads affected the region’s landscape and remoteness.

On that rafting trip, Paul and I spent 11 days floating down the Franklin without seeing another human being. The side canyons, waterfalls, rainforests, eagles, platypuses and glow-worms had me entranced.

Paul pointed out the flood levels of the proposed dams high on the Franklin’s ravine walls and, just after we passed the Franklin’s confluence with the mighty Gordon River, we were suddenly confronted by the jackhammers, helicopters and explosives of dam builders looking for the best place to secure the first of the four proposed dams.

No longer entranced, I was horrified. We came back to civilisation determined to publicise the plight of the wild rivers.

Seven years of campaigning to save the Franklin River from a similar fate to that of Lake Pedder culminated in the 1982 blockade at Warner’s Landing, in which 1300 people were arrested.

Domestic and international focus on the campaign grew as popular celebrities including Sir Yehudi Menuhin, Barry Humphries, Eartha Kitt, Claudio and Lesley Alcorso, and David Bellamy (his arrest created headlines in London) backed the river’s rescue. More positive headlines were created when founder of Australian Geographic Dick Smith arrived in his helicopter and helped set up the remote blockade’s radio communications.

Franklin Rive comes to life in colour

Yet it was the river itself that saved the day. The advent of colour television brought the river’s natural beauty into Australia’s lounge rooms. The first ever colour campaign poster, featuring a photo of the Thunderush rapids, in the Franklin’s Great Ravine, was produced in 1979 by Sydney’s Southwest Committee.

In 1980, after a number of solo rafting trips on the Franklin, Tasmanian photographer Peter Dombrovskis captured the now legendary photograph Morning Mist, Rock Island Bend (page 64); it was reproduced an estimated 1 million times for the campaign.

I went halfway up Mt Wellington, to a Hobart suburb called Fern Tree, to visit Peter at home and look through his latest batch of Franklin River photos. I was riveted by his image of Rock Island Bend (the name I gave this scenic gem, because it would otherwise had its 1840s convict label, the Pig Trough).

Peter didn’t think it was his best photo but I instantly saw its mystical qualities. I knew this bend in the river would indisputably be flooded by the proposed first dam, which added to the photograph’s impact. The image embodies the legendary relationship photography and conservation have in Tasmania.

By mid-1983, determined Tasmanian premier Robin Gray had spent $70 million ($200 million today) on preliminary dam works. However, on 1 July that year, the four-to-three decision of the High Court judges endorsed the newly elected Commonwealth government’s power (under prime minister Bob Hawke) to stop the dam in order to protect the Franklin’s World Heritage values. In July this year, we celebrated the 30th anniversary of that historic decision.

In his majority judgment, justice Lionel Murphy wrote, “The encouragement of people to think internationally, to regard the culture of their own country as part of world culture, to conceive a physical, spiritual and intellectual heritage, is important in the endeavour to avoid the destruction of humanity.” The justice regarded the rich Aboriginal heritage in the Franklin Valley wilderness, as well as the area’s wild beauty, as part of our culture.

And, thankfully, the majestic wild peak of Frenchmans Cap (1446m), which is drained entirely by the Franklin, was saved from the indignity of being surrounded by the methane-belching moat of a dammed river and drowned forests.

The inundation of Lake Pedder in 1972 created a national furore which, in turn, helped save other wild places as well as the Franklin River: the Daintree, Fraser Island, Kakadu, Victoria’s Little Desert and the subtropical forests of NSW.

In Tasmania, it led to the formation of the world’s first Greens party.

A decade after Lake Pedder disappeared, parts of Tasmania’s wilderness were declared World Heritage areas for the first time and soon after that, the Franklin River was saved. However, there was a backlash from developers. In the decades that followed, state governments introduced draconian penalties, including up to six months in jail, for anyone who refused to get out of the way of bulldozers invading wilderness to construct new mines or dams, or were facilitating logging or invasive tourism operations.

Saving the Franklin paved the way to conserving other places

These operations are part of a dominant world culture of profiteering from nature, based on corporate power over elected and non-elected governments. Most conservationists are sidelined but this year’s magnificent win by campaigners, not least the Goolarabooloo people, against the Woodside gas factory and port on the Kimberley coast, WA, went against that tide.

When we gained the balance of power in the Tasmanian Parliament in 1989, the Greens ensured the inclusion of magnificent wild areas such as the Denison River valley, the Walls of Jerusalem and the eastern half of Macquarie Harbour, in the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area, expanding it from 7160sq.km to 13,840sq.km.

In July 2013 another 1700sq.km were added. The newly protected areas comprise some of the tallest flowering forests on Earth, including those of the Styx Valley, the Upper Florentine Valley and the Great Western Tiers, together with Mount Field National Park and some smaller reserves.

Today, the Tasmanian wilderness is one of the world’s greatest protected temperate areas. But protecting the island state’s wild places will not be complete until the Tarkine wilderness, in the north-west, is given World Heritage listing.

The Tarkine comprises 4500sq.km of inspiring natural country, including the nation’s largest temperate rainforest. Earlier this year, the Australian Heritage Council advised then environment minister Tony Burke to list the Tarkine. He rejected that advice and opened most of the Tarkine to mining.

The Tarkine is a wonderful place, from its wild coast to its ranges and buttongrass plains, from its pristine west-flowing rivers and lagoons to its rare and endangered species, which include the world’s largest crayfish, the Tasmanian devils, the quolls and the giant wedge-tailed eagle.

Its coastline is the land of the Tarkiner people, whose middens, rock carvings and hut sites are today being eroded by off-road vehicles.

In 2013, the first two Tarkine mines have been authorised by state and federal ministers “for the environment”. What will save the Tarkine? Only one formula will work and that is Franklin campaign-style public action: lobbying of politicians, funding of campaign groups (including Save the Tarkine), voting for candidates dedicated to its protection and, if need be, peacefully getting in the way of the destruction of this national heirloom. Although, perhaps before all else, the first thing to do is to visit the Tarkine, because to go there is to want to save it.

Bob Brown arrested in the Franklin blockade

I was arrested in the Franklin blockade in 1982–83 and spent 19 days in Risdon Prison (600 others also went to Risdon). Arrested twice more in the 1990s for peacefully obstructing bulldozers that were compromising the Tarkine’s remote and pristine qualities with roads and logging, I spent a further 11 days in Tasmanian jails with a bunch of other wilderness-loving citizens. The concrete walls of those prisons were the antithetic cultural statement to the wild places we had been defending.

Why is there so little public alarm about the death of the wild world? This was the question that was obvious to Paul Smith and me as we sat by the Franklin, and that I pondered in those cells, but which now challenges us all with greater urgency than ever.

Nearly two centuries ago Thoreau wrote, “in wildness is the preservation of the world”. It follows that in wildness is the saving of ourselves. It is time we all got a little wilder about the plight of planet Earth, its wild places and all its creatures, ourselves included.

Notes from the field: Koala-loving community

Writer Liz Ginis grew from toddler to teen in the green pastures and eucalypt forests of the Bellinger Valley on the NSW Mid North Coast.

Scientists pose as cleaner fish to perform whale shark ultrasounds

Marine scientists have used underwater ultrasounds to monitor the health of whale shark populations at Ningaloo Reef in Western Australia.

Mightier than the saw

Sawfish are among the world’s most unusual marine creatures. But some species are also among the most threatened animals on the planet.

Watch Latest Web Stories

Birds of Stewart Island / Rakiura

Endangered fairy-wrens survive Kimberley floods

Australia’s sleepiest species

2024 Calendars & Diaries - OUT NOW

Our much loved calendars and diaries are now available for 2024. Adorn your walls with beautiful artworks year round. Order today.

In stock now: Hansa Soft Toys and Puppets

From cuddly companions to realistic native Australian wildlife, the range also includes puppets that move and feel like real animals.

Essays On Air: how archaeology helped save the Franklin River

Research fellow, Deakin University

Disclosure statement

Billy Griffiths does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Deakin University provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

On 1 July 1983, in a dramatic four-three decision, the High Court of Australia ruled to stop the damming of the Franklin River. It ended a long campaign that helped bring down two state premiers and a prime minister, as well as overseeing the rise of a new figure on the political landscape – the future founder of the Greens, Bob Brown.

But the battle for the Franklin River runs far deeper than simply providing the backdrop for a political tug-of-war.

In today’s episode of Essays on Air - the audio version of The Conversation’s Friday essay series - writer and historian Billy Griffiths reads his essay on how archaeology helped save the Franklin River . Its rich history and significance to the Tasmanian Aboriginal community made the proposed dam a controversy that captivated the nation.

Today’s episode was recorded and edited by Sybilla Gross. Find us and subscribe in Apple Podcasts, in Pocket Casts or wherever you get your podcasts.

Additional Audio

Snow by David Szesztay

Cave Drips by everythingsounds

Climbing gear by Benboncan

Cave footsteps by Timbre

Cave River by jpdeglet69

Pottery sounds by Tumbleweed3288

Loud River by FractalStudios

Panting by Drkvixn91

Fire crackling by daenerys

Rain by acclivity

Howling Wind by DBlover

Newspaper by deleted_user_1116756

Parliament sounds by AusQuestionTime

Protest by dnlburnett

Rally clap by mw_1984

Correction: An earlier version of this story featured the wrong picture as its lead image. The error was made in the production process. The Conversation apologises for the mistake, and thanks readers who brought it to our attention.

- Conservation

- Environment

- Aboriginal heritage

- Friday essay

- Essays On Air

Director of STEM

Community member - Training Delivery and Development Committee (Volunteer part-time)

Chief Executive Officer

Finance Business Partner

Head of Evidence to Action

Effective Action for Social Change: The Campaign to Save the Franklin River

Introduction.

Learn lessons from one of the largest and most successful nonviolent direct action environmental protests in Australian history – the Franklin River campaign. This unpublished book was written by five activists who were deeply involved, providing valuable insights into the activities that made up the campaign as well as the political dynamics and philosophical dimensions.

The Franklin Dam Dispute and the Protagonists: A Summary

Tasmania is an island about the size of England which lies just off the south-east corner of the Australian mainland. Often cold and wet, its south-west corner is largely wilderness, a remnant of Gondwanaland and a relative of Fjordland in NZ and Patagonia in South America.

Rough terrain and a small European population have allowed the region to remain intact since the first whaling and convict settlements in Tasmania in the early I 800’s, but pressures for exploitation have grown in the last twenty years. Mining, logging, and hydro-electric development are all threats.

Throughout Tasmania fast-flowing rivers have become an engineer’s paradise of pipes and concrete, and in 1972, after a long fight, the first big hydro scheme in the South West drowned beautiful Lake Pedder. Given blank cheques by successive governments, Tasmania’s government electricity authority, the Hydro-Electric Commission (HEC), planned dams for every free-flowing river in the state, including the Franklin and the Lower Gordon.

These are magnificent rivers of rainforests and gorges. Virtually the entire catchment of the Franklin is wilderness.

Environmentalist opposition to these plans was chiefly voiced through the Tasmanian Wilderness Society (TWS). TWS became a cohesive and powerful pressure group as the possible flooding of the Franklin grew into an issue which polarised the Tasmanian community. TWS had several public identities in its ranks, including .Bob Brown, who has since become a Tasmanian parliamentarian and has worn the media tag of ‘Australia’s leading conservationist’.

At the time of the Franklin Blockade, a civil disobedience action on the banks of the Franklin and Gordon Rivers, the TWS Campaign was six years old, and it was over fifteen years since the first environmental battles in the South West.

TWS’s major opponents wee the HEC and the Tasmanian Government led by right-wing confrontationalist, Robin Gray. Gray’s Liberal Party had been elected only seven months before the Blockade began. His rise to power followed the internal collapse of the Australian Labor Party in Tasmania. This collapse was partly due to divisions caused by the Franklin dispute.

The Federal Government remained in the wings of the Franklin battle till its later stages because of the Australian federal system of government that gives the states power in most land-use planning decisions. Leadership in Canberra changed during the Franklin Campaign. For most of the time the Australian Prime Minister was the leader of the conservative Liberal – National Party coalition, Malcolm Fraser. At the time of the Blockade Fraser was replaced by the populist ALP leader. Bob Hawke, whose election was a fortunate coincidence with the climax of the TWS Franklin Campaign.

For readers unfamiliar with the political context of the Franklin dispute, the first half of Chapter 12, ‘Parliamentary Pressure and the Franklin Campaign’, will provide the necessary background.

- Acknowledgements

- The Franklin Dam Dispute and the Protagonists Timeline

- 1. INTRODUCTION

- PART I: ONE VOICE, ONE MIND, ONE PEOPLE?

- 2. Introduction

- 3. Logistics and Strategy: Building a Direct Action

- 4. Training: Preparing People for a Protest

- 5. Stopping Work?

- 6. Consensus: Resolving The Differences?

- PART II: CIVIL DlSOBEDIENCE – THE STRENGTH OF THE BLOCKADE

- 7. Introduction

- 8. Civil Disobedience and the Courts

- 9. Understanding the Police: the Value of Diplomacy

- 10. The Jail Protest: Further Civil Disobedience

- PART III: THE WIDER CONFLICT

- 11. Introduction

- 12. Parliamentary Pressure and the Franklin Campaign

- 13. Events Into Images: Media Coverage of the Franklin Campaign

- 14. Local Allies

- 15. An Alliance with the Labour Movement?

- 16. CONCLUSION

- Annotated Bibliography

Please note that this document is a scanned typewritten manuscript that may not be accessible with screen reading software. Please contact us if you would like help accessing the document.

Download Report

Read the full report.

Explore Further

Read more about the blockade – In 2013 Franklin blockader Alice Hungerford produced the book UpRiver: Untold stories of the Franklin River activists. Including numerous photos this oral history brings together memories from the group of activists who camped in the forest for months on end to support and organise daily blockading actions.

Watch a 20-minute documentary, including footage of various blockade actions. It can be viewed in two parts.

A new full-length documentary entitled Dark Water was produced about the blockade in 2022. For more information visit – https://franklinriver.movie/

Listen to this ABC Podcast Series called Saving the Franklin Revisit the biggest environmental movement Australia has ever seen: the 1982 Franklin River Blockade. This story is nuts. Missing people, death threats, savage political moves and young people flooding into Tasmania to put their bodies in front of bulldozers. Jo Lauder investigates how this movement beat the odds and came to inspire a new generation of environmental activists that have shaped Australian politics through to today.

More in the Commons Library

- Franklin River Campaign

- Tasmanian Wilderness Society blocks dam construction (Franklin River Campaign) 1981-83

- The Franklin River Story (Easy Read) Easy Read uses clear, everyday language matched with images to make sure everyone understands.

- Campaigns that Changed Tasmania

Related Resources

Share resource.

- Nonviolent Direct Action

- Alliances_Allies_Coalitions_Partnerships

- Civil disobedience

- Direct action - Non violent NVDA

- History - Australia

- Lessons learned_Reviews_Reflections

- Movements_Campaigns - Environment_Nature

- Tasmania - Franklin River Region

- Wilderness Society (The) TWS

- Author: Claire Runciman , Gill Shaw , Harry Barber , John Stone , Linda Parlane

- Location: Australia

- Release Date: 1986

- Resource: Effective-Action-For-Social-Change-Franklin-campaign-.pdf

© All Rights Reserved

Contact a Commons librarian if you would like to connect with the author

- Arts & Creativity

- Campaign Strategy

- Coalition Building

- Communications & Media

- Digital Campaigning

- First Nations Resources

- Fundraising

- Justice, Diversity & Inclusion

- Lobbying & Advocacy

- Research & Archiving

- Story & Narrative

- Theories of Change

- Working in Groups

We’re sorry, this feature is currently unavailable. We’re working to restore it. Please try again later.

- Our network

The Sydney Morning Herald

- Environment

- Conservation

This was published 1 year ago

From the Archives, 1982: Confrontation on the Franklin River

Many people helped save the franklin, a wild, beautiful river winding through the remote south-west of tasmania but one name stands out – dr bob brown., by peter ellingsen, save articles for later.

Add articles to your saved list and come back to them any time.

First published in The Age , December 17, 1982.

Bemused by arrests in wilderness

Bob Brown at the Gordon River, upstream from the junction of the Franklin, in Tasmania, a wilderness saved through what he calls 'defiant optimism.' Credit: Joe Armao

STRAHAN. — Dr Bob Brown, the mainlander medico-turned-greenie, yesterday got himself arrested — an event that has managed to eclipse all else in Tasmania this week. And, some would say, anything else since its favorite son, Joe Lyons, became Prime Minister half a century ago.

Dr Brown, who has not been treated very sympathetically by the Tasmanian Press, grinned and waved his way into the restricted Franklin Basin zone, then out of it again — in the back of a police launch.

While the HEC public relations man, Peter Read, enthused over the accommodation dam workers were enjoying on the site, conservationists led by Dr Brown sang and clapped their way into every newspaper and television set in the country.

“I’m just another citizen,” Dr Brown, the director of the Tasmania Wilderness Society, said into waiting microphones. “It is my birth right to be here — the wilderness does not belong to the HEC or a few politicians.”

And most of those listening, perhaps even the policeman who shook hands with Dr Brown before taking him to jail, agreed.

Spirits were high as Dr Brown went on: “I still wouldn’t put it past (the Prime Minister) Mr Fraser to be astute enough to reverse this extraordinary (dam) decision.

Back at the society’s headquarters in Strahan, telegrams poured in, including the one from Melbourne reading: “make sure you comb your hair and brush your teeth — all Australia is watching.”

Another telegram from the Australian Antarctic base at Davis Station read: “Will be there in spirit if not body, Saturday. Concerned few, David Station, Antarctica.”

Dr Brown, who wore a tie especially for the occasion, confirmed that the society was spending $2000 a day on the fight and welcoming up to 50 new supporters every morning.

Even with an estimated 150 greenies in Hobart’s Risdon Jail (one apparently in solitary confinement for refusing to call the superintendent “Sir”) about 300 remained ready to continue the battle in Strahan.

Dr Brown will probably spend a week cooling his heels in prison rather than agree to a bail condition of not returning to the area.

Before heading off to court in Queenstown, he tried to explain his stand by leading a party from the river bank, through the rain forest to a 3000-year-old Huon pine.

“This tree looked much the same as it does now when Abel Tasman sighted Tasmania in 1642,” he explained. “If the dam goes ahead it won’t have much longer to live.”

Protesters are being told to carry an extra pair of socks and underwear to make that part of their campaign in the fast-filling Hobart jail a little more comfortable.

The fuss being made nationally and overseas over the Franklin is distressing for many people here who have never paid much attention to a wild river winding through the remote south-west of the State.

Ask a Taswegian what he thinks about the proposed Gordon-below-Franklin dam and likely as not, his eyes will glaze over and he will shrug his shoulders. It is a case of dams being a four-letter, but somehow still respectable, word.

In Strahan, the closest town to the area listed this week by the World Heritage Council, you are an outsider if you live 40 kilometres away in Queenstown. Anyone foolish enough to travel further is going “away”, and deserves to be lumped in with that most distrusted of species, “main-landers”.

The 400 residents of Strahan, mostly fishermen, timber workers and unemployed, can’t come to grips with all the fuss being made about a dam their State Government says will flood a “leech-ridden ditch” and create jobs.

They particularly cannot comprehend the hundreds of young volunteers who camp on the edge of town and keep the south-west in the news by choosing jail rather than agree to a Hydro-Electricity Commission demand to stay out of the Franklin Basin.

Most Viewed in Environment

Timeline of the Franklin Dam Controversy

>> 1978; the Tasmanian Hydro Electric Commission (HEC) announce their intention to harness the Franklin River for hydroelectricity, proposing two dam sites, the Gordon below Franklin Dam (105m high) a few km below the Franklin Gordon confluence and Dam #2 at the end of the Mount McCall Track.

>> one of most significant successful environmental campaigns in Australian history, led by The Wilderness Society under Bob Brown starts

>> June 1980; an estimated 10,000 no-dams people march the streets of Hobart

>> the Labor state government, under premier Doug Lowe, agrees to place the Franklin River in a new “Wild Rivers National Park”. Instead of the original ‘Gordon below Franklin’ proposal, Lowe now backs the ‘Gordon above Olga’ scheme.

>> 1981, Senate inquiry into “the natural values of south-west Tasmania to Australia and the world” and “the federal responsibility in assisting Tasmania to preserve its wilderness areas of national and international importance” is initiated by Australian Democrats Senator Don Chipp

>> early 1981 Kevin Kiernan discovers Aboriginal caves on the Lower Franklin, containing Aboriginal hand stencils as well as remnants of campfires and stone tools between 8,000 and 24,000 years old. Concerns begin to be raised about habitat loss for endangered species.

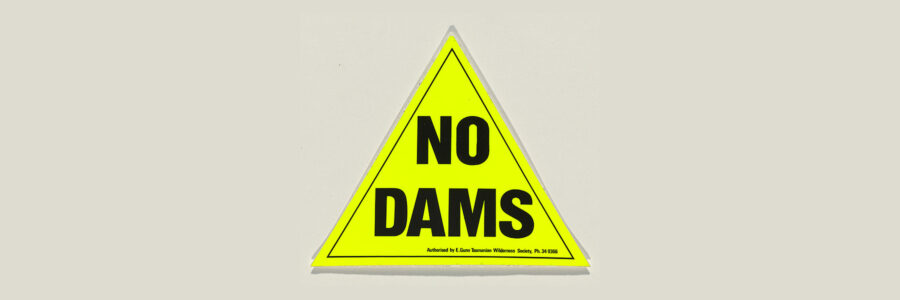

>> 12 Dec 1981; In the Power Referendum 1981 around 47% of Tasmanians vote for the original Gordon below Franklin scheme, about 8% for the Gordon above Olga scheme, and 45% vote informally with more than 33% of voters writing “No Dams” on their ballot papers.

>> 15 May 1982 in the state election Harry Holgate, who had replaced Doug Lowe as Premier in 1981, is defeated by Robin Gray’s Liberal government. Dam building continues and the necessary legislation gets passed. For Robin Gray the Franklin River is ‘nothing but a brown ditch, leech-ridden and unattractive to the majority of people’.

>> Federal Government under Malcolm Fraser offers the Gray government $500 million to stop the Franklin dam. Gray refuses the offer and Fraser declines any further action, claiming the dam was a state matter.

>> During 1982 the anti-dam campaigns are ramping up with people like Bob Brown, David Bellamy and Dick Smith speaking out nationally. The iconic “No Dams” triangle sticker is printed.

>> 14 December 1982; the Democrats’ World Heritage Protection Bill passes the Australian Senate, giving the Governor General the power to issue proclamations for particular places.

>> 14 December 1982; the World Heritage Commission accepts the nomination of the South West for heritage listing

>> 14 December 1982; start of the blockade of the dam site at “Warners Landing” on the Gordon River, drawing an estimated 2,500 people from Tasmania, interstate and overseas.

>> January 1983; around fifty people arrive at the blockade each day. The state government makes things difficult for the protesters, passing several laws and enforcing special bail conditions for those arrested. Bulldozers arrive at the dam site. A total of 1,217 arrests are made, including David Bellamy, Claudio Alcorso, Andrew Lohrey, and Bob Brown, many simply for being present at the blockade.

>> February 1983; approximately 20,000 people attend a Hobart rally against the dam.

>> 1 March 1983; “G-Day” a day of anti-dam action, 231 people are arrested as a flotilla of boats takes to the Gordon River. In Hobart, the Wilderness Society flag is flown above the HEC building.

>> 2 March 1983; publication of an iconic photograph, Morning Mist, Rock Island Bend, Franklin River by Peter Dombrovskis accompanied by the caption “Could you vote for a party that would destroy this?” backed by The Wilderness Society

>> 5 March 1983, the Australian Labor Party under Bob Hawke wins the federal election. Hawke’s government first passes regulations under the existing National Parks and Wildlife Conservation Act 1975, and then passes the World Heritage Properties Conservation Act 1983, which prohibits Franklin River dam-related clearing, excavation and building activities that had been authorised by Tasmanian state legislation.

>> The Tasmanian government ignores both the federal regulations and legislation and HEC continues to work on the dam.

>> 31 May 1983 The issue is brought before the High Court, Commonwealth v Tasmania. The government of Tasmania claims that as the right to legislate for the environment was not named in the Constitution, and was thus a residual power held by the states, that the World Heritage Properties Conservation Act 1983 was unconstitutional. The federal government, however, claimed that they had the right to do so, under the ‘external affairs’ provision of the Constitution as, by passing legislation blocking the dam’s construction, they were fulfilling their responsibilities under an international treaty (the UNESCO Convention for the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage, Australia having signed and ratified that convention and the Franklin River having been listed on it). The Commonwealth government also argued that the federal legislation was supported by the constitutional powers of a federal government to pass laws about corporations and about the people of any race (in this case the aboriginal race, whose sacred caves along the Franklin would have been inundated).

>> 1 July 1983, in a landmark decision, the High Court on circuit in Brisbane rules in the federal government’s favour by a vote of 4 (Judges Mason, Murphy, Brennan and Deane) to 3 (justices Wilson and Dawson with Chief Justice Gibbs). This ruling gave the federal government the power to legislate on any issue if necessary to enforce an international treaty and has been the subject of controversy ever since.

>> the High Court ruling finally ends the Franklin dam’s construction. The Franklin River can continue to run free!

Read more about the Franklin River Campaign, the Wilderness Society

Skip to Main Content of WWII

The 1945 san francisco conference and the creation of the united nations.

In April 1945, fifty nations gathered in San Francisco, California and created The United Nations.

Top image: “UNITED NATIONS - WE 1,750,000,000 PEOPLE FOR UNDERSTANDING FOR PEACE,” F. C. Veit, 1943-1945, National Archives and Records Administration, cataloged under the National Archives Identifier (NAID) 515906.

Between April 25, 1945 and June 26, 1945, delegates of 50 nations met in San Francisco, California, at the United Nations Conference on International Organization. Working off previous proposals outlined in the Atlantic Charter, the Dumbarton Oaks proposals, the Yalta Agreement, and amendments suggested by governments in attendance, the Conference agreed upon the Charter of the United Nations and the Statute of an International Court of Justice, which effectively created the United Nations (UN).

Various international organizations existed before the UN, yet many were limited in scope and power. In 1899, for example, the International Peace Conference was held in The Hague to create instruments for peacefully settling international crises, preventing wars, and codifying rules of warfare. The International Peace Conference also adopted the Convention for the Pacific Settlement of International Disputes and established the Permanent Court of Arbitration, which began work in 1902.

In 1919, representatives at the Paris Peace Conference founded the League of Nations under the Treaty of Versailles. Designed to keep the peace in the aftermath of World War I, the League—often seen as the predecessor to the United Nations—went into effect a year later. Compared to the United Nations, however, the League failed to secure or retain membership for certain major powers, had confusing procedures for negotiating disputes between states, and lacked sufficient powers to prevent or terminate hostilities. Even though the League of Nations failed to prevent World War II, the Allies learned from the failures of the League and, under the leadership of US President Franklin D. Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, began planning a successor organization in the summer of 1941.

The League of Nations

The first international organization designed “to promote international cooperation and to achieve peace and security” was the League of Nations. Championed by US President Woodrow Wilson, the League was made up of sovereign states devoted to the settlement of disputes and the prevention of war. The organization’s main aim was to create a new process for conducting foreign affairs in order to abolish war and encourage disarmament in the wake of the destruction wrought by World War I.

The establishment of the League of Nations marked a significant turning point in international relations. In contrast to how intergovernmental affairs had previously been conducted, often through hidden agreements and fragile alliances, governments who joined the League agreed to sit at one table and find peaceful solutions to political problems and disputes. In January 1920, 42 nations had already joined the League of Nations.

The League of Nations achieved successes in international cooperation in its early years through conferences, intergovernmental committees, and meetings with experts in areas such as transport and communications, health, economic and financial affairs, and intellectual cooperation. The organization also peacefully resolved regional disputes between Sweden and Finland and between Greece and Bulgaria.

The League of Nations, however, was plagued with many problems. Although the organization had the power to offer arbitration through the Permanent Court of International Justice and apply trade sanctions against countries that went to war, all declarations and decisions had to be unanimous. This, coupled with the fact that the League had no military, limited the extent to which the League could stop foreign aggression or enforce any decisions it made.

Another major issue was that the institution failed to secure or retain the membership of certain major powers whose participation and cooperation were essential to make it an effective instrument for preserving the peace. Although Woodrow Wilson was an enthusiastic supporter of the League of Nations, the United States never officially joined the League due to opposition from isolationists in Congress. Moreover, after the League condemned Japan’s invasion of Manchuria in 1932 and Italy’s invasion of Abyssinia in 1935, both countries left the organization. Hitler also renounced Germany’s membership in 1933, leaving the rest of the League’s members powerless to stop German aggression in Austria and Czechoslovakia.

“Woodrow Wilson, President of the United States,” Harris & Ewing, 1919, United States Library of Congress 's Prints and Photographs division , digital ID cph.3f06247 .

Despite the League’s failure to prevent World War II, it did provide a blueprint for another international peacekeeping organization. As Stewart M. Patrick, a senior fellow in global governance, stated in an interview with Time Magazine:

“The League of Nations is significant because, even though it failed, it was the first time a bunch of sovereign nations got together and said, ‘We’re sovereign nations, but we’re going to try to combine our power to try to keep the peace.’ It also had some modest successes particularly dealing with certain territorial disputes. The League was not in vain if you consider that there were lessons learned from its failings.”

Preparations for a United Nations, 1942-1945

The outbreak of World War II in 1939 generated a desire among the Allied nations to create a new international body that would be more adequately equipped to maintain international peace in the future. The concept of international peace and security laid out in the UN Charter began to develop with the ideas expressed in the Declaration of St. James Palace and the Atlantic Charter of 1941, both of which expressed the need for global cooperation to ensure peace. Subsequent meetings with nations at war with Germany and Japan continued throughout the conflict at Moscow, Tehran, Dumbarton Oaks, and Yalta, culminating with the creation of the United Nations at the San Francisco Conference in April 1945.

On June 12, 1941, the representatives of Great Britain, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, the Union of South Africa, General de Gaulle of France, and the exiled governments of Belgium, Czechoslovakia, Greece, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, and Poland met at the historic St. James Palace. During the meeting they signed a declaration which stated, in part:

“The only true basis of enduring peace is the willing co-operation of free peoples in a world in which, relieved of the menace of aggression, all may enjoy economic and social security; and that it is their intention to work together, and with other free peoples, both in war and peace to this end.”

Two months later, on August 14, 1941, Roosevelt and Churchill issued a joint declaration, known as the Atlantic Charter, following a meeting of the two heads of government in Newfoundland. In addition to outlining US and British war aims, the charter also provided a vision for a postwar world order. It specifically assured that both countries shared “certain common principles in the national politics of their respective countries on which they base their hopes for a better future for the world.” This statement also included clauses pertaining to equal trade opportunities, free communications, economic and social cooperation, and collective security against aggression. The eighth paragraph of the document specifically referred to the future “establishment of a wider and permanent system of security.”

According to Philips Bradley, “the fact that the leaders of the United States and Great Britain subscribed to these principles jointly gave the Atlantic Charter an importance far beyond a simple personal declaration” since the United States affirmed its commitment to a “workable world security system,” when it was not yet at war.

On January 1, 1942, twenty-six countries, including the United States, Great Britain, China, and the Soviet Union agreed to the principles outlined in the Atlantic Charter in a document which became known as the Declaration of the United Nations or the Declaration by United Nations. The Declaration by United Nations contained the first official use of the term “United Nations,” a phrase coined by Franklin D. Roosevelt. Between 1942 and 1945, 21 other countries signed the document. As planning for the 1945 San Francisco Conference began, only states which had declared war on Germany and Japan prior to March 1945 and subscribed to the United Nations Declaration were invited to take part. Thus, the Declaration was a crucial step in securing global support for the founding of a new postwar international organization designed to promote peace.

“The Atlantic Charter Poster,” 1942-1945, NARA & DVIDS Public Domain Archive. The Declaration of the United Nations, January 1, 1942, Washington DC, UN Photo/VH. The original 26 signatories included: The United States, the United Kingdom of Great Britain, Northern Ireland, the Soviet Union, China, Australia, Belgium Canada, Costa Rica, Cuba, Czechoslovakia, the Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Greece, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, India, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Nicaragua, Norway Panama, Poland, the Union of South Africa, and Yugoslavia. Subsequent adherents to the declaration were Mexico, the Philippines, Ethiopia, Iraq, Brazil, Bolivia, Iran, Colombia, Liberia, France, Ecuador, Peru, Chile, Paraguay, Venezuela, Uruguay, Turkey, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Syria, and Lebanon.

Negotiations on the future international organization continued at Moscow, Tehran, and Dumbarton Oaks in Washington, DC, between 1943 and 1944. At the close of the Moscow Conference, held in the fall of 1943, the foreign ministers of the United States, Russia, Great Britain, and China issued a statement recognizing:

“the necessity of establishing at the earliest practicable date a general international organization, based on the principle of sovereign equality of all peace-loving States, and open to membership by all such States, large and small for the maintenance of international peace and security.”

This was the first time the idea of establishing an international organization to keep peace after the end of World War II was explicitly expressed in an official document. Shortly thereafter, all four countries appointed national committees composed of experts that separately worked on drafting a charter for the future organization. Within a year, representatives of the United States, Great Britain, the Soviet Union, and China met at the Dumbarton Oaks estate in Washington, DC and issued the Dumbarton Oaks Declaration, a detailed blueprint which became the framework for the San Francisco Charter.

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin pose outside on the grounds of the Livadia Palace during the Yalta Conference. “Yalta Conference, February 4, 1945, Yalta, Ukraine, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, Photograph Number: 91461.

Negotiations concerning the future United Nations continued at the Yalta Conference in February 1945. On February 11, 1945, Roosevelt, Churchill, and Stalin, together with their foreign ministers and chiefs of staff, declared:

“We are resolved upon the earliest possible establishment with our Allies of a general international organization to maintain peace and security. We believe that this is essential, both to prevent aggression and to remove the political, economic, and social causes of war through the close and continuing collaboration of all peace-loving peoples.”

At Yalta, “the Big Three” also agreed that “a Conference of the United Nations should be called to meet at San Francisco in the United States on 25 th April, 1945, to prepare the charter of such an organization,” proposed a Security Council for the future United Nations, and outlined voting procedures.

Invitations for the San Francisco Conference were sent out on March 5, 1945. With the death of President Roosevelt on April 12, 1945, there was fear that the conference might be postponed. President Truman, however, decided to carry out all the arrangements already put in place, and the conference opened two weeks later.

San Francisco Conference 1945

The goal of the San Francisco Conference, formally known as The United Nations Conference on International Organization, was to set the foundations and establish a framework for the United Nations. There were 850 delegates from 50 countries at the Conference—26 of which had signed the original 1942 Declaration of the United Nations. At the time of the conference, there was no internationally recognized Polish Government, therefore, despite being one of the original signatories of the Declaration of United Nations, Poland did not have a representative at the conference. The country was later admitted and allowed to be considered an original member, bringing the total number of founding member states to 51.

To accomplish the task of creating a founding charter for the United Nations, work at the San Francisco Conference was organized into four committees. The Conference in Plenary Session was the highest body, which was in charge of the final voting and adoption of the text of the Charter of the United Nations. Below, there were four main committees: The Steering Committee dealt with questions regarding policy and procedure; the Executive Committee prepared recommendations for the Steering Committee; the Coordination Committee assisted the Executive Committee, and the Credentials Committee verified the credentials of all delegates. The foreign ministers of the four Allied sponsors, US Secretary of State Edward Reilly Stettinius, Jr. , Anthony Eden of Great Britain, Vyacheslav Mikhaylovich Molotov of the USSR, and T.V. Soong of China, took turns acting as chairman of the plenary meetings.

According to Bradley, one of the major issues facing delegates “arose out of the difficulty of reconciling the theory of international law-that all nations are equal- with the facts of international life- that some are more powerful and influential than others.” On the one hand, more powerful countries recognized that they would have more responsibility for supplying military forces for keeping the peace and wanted to have significant input about when, where, and how they would use their resources when called to do so. Closely related, was the prevalent belief among larger nations that they should have the right to veto the use of international forces against themselves. On the other hand, smaller nations insisted that they were sovereign equivalents to larger nations and should have an equal say in peacekeeping missions.

To solve this issue, The Charter of the United Nations created a General Assembly of all member states, each with one vote, which acts as “a world legislature without lawmaking power.” The Charter also created an executive organ called the Security Council, with five permanent and six non-permanent, rotating members. The five permanent members included China, France, the United States, the Soviet Union, and Great Britain—all of which have veto power. Today, the five original permanent members remain the same, but as the UN expanded the number of non-permanent members to ten.

“Rt. Hon. W.L. Mackenzie King addressing the United Nations Conference on International Organization ,” Nicholas Morant, 1945, Phototheque / Library and Archives Canada, C-022715.

The Security Council was designed to be the main body responsible for the maintenance of international peace and security and, under the Charter of the United Nations, all member states are obligated to comply with Security Council decisions. The Charter also established a Military Staff Committee attached to the Security Council, intended to direct the use of armed forces on behalf of the United Nations, a significant component missing from the League of Nations.

The other main governing body established at San Francisco was the International Court of Justice, which is responsible for settling, “in accordance with international law, legal disputes submitted to it by States and to give advisory opinions on legal questions referred to it by authorized United Nations organs and specialized agencies.”

Delegates to the San Francisco Conference also had to deal with other issues including how to incorporate regional and bilateral treaties into the new international organization and questions regarding what should be done with former enemy colonies and “dependent peoples,” who had been under the supervision of one of the victor nations. How member states would cooperate and compromise on economic and social matters also had to be addressed. To address these issues, the Charter created an 18-member Economic and Security Council, a Trusteeship Council to oversee colonial territories, and a Secretariat under a Secretary General.

At the end of the San Francisco Conference, on June 25, 1945, the Charter was unanimously adopted at the San Francisco Opera House. The next day, it was signed at the Herbst Theater auditorium of the Veterans War Memorial. The United Nations, however, did not come into existence until October 24, 1945 (now annually observed as United Nations Day), when the governments of China, France, Great Britain, the Soviet Union, and the United States and a majority of the other signatory states had ratified the Charter.

After four years of planning, the United Nations materialized, marking a momentous step in development of peaceful international relations. This “great alliance,” in Roosevelt’s words, would guarantee “a true peace based on the freedom of man.” Utilizing the effective aspects of the League of Nations and adapting the features that did not work, the Allied nations successfully established a lasting organization to promote peace, justice, and better living for all humanity.

Jennifer Popowycz, PhD

Jennifer Popowycz, PhD is the Leventhal Research Fellow at The National WWII Museum. Her research focuses on the Eastern Front and Nazi occupation policies in Eastern Europe in World War II.

Explore Further

Eleanor Roosevelt's Response to Germany's Invasion of Poland

In her September 2, 1939, My Day column, Eleanor Roosevelt reacts to the news of Germany's invasion of Poland, sharing her dismay at Adolf Hitler's actions and expressing sorrow for the European nations facing the crisis.

The Allies of World War II

World War II was a global conflict involving nearly every country in the world. But who was on each side—and why?

The Axis Powers of World War II

The Neutrality Acts of the 1930s

This legislation was the culmination of efforts by American citizens, activists, and politicians across the political spectrum to insulate the United States from foreign conflicts and prevent the country from being drawn into another global war.

Meet the Author: Stephen O. Sears, 'Sunniland'

The novel Sunniland follows a young geologist in Florida monitoring the development of a new oil well while facing a German U-boat rampage taking place in the nearby Gulf of Mexico in the spring of 1943.

Landing Vehicle Tracked: Armored Ship-to-Shore Movement

On display in the John E. Kushner Restoration Pavilion, The National WWII Museum’s LTV-4 is a testament to American innovation.

Operation Dragoon: Invasion of Southern France

Originally designated Operation Anvil and intended to support the hammer blow of the Normandy landings two months earlier, the renamed Operation Dragoon fulfilled an American desire for a lodgment in southern France that shifted forces from the strategic cul-de-sac of Italy.

The 'Lost Olympics' of 1940 and 1944

The International Olympic Committee's (IOC) plans for the 1940 Summer Games took many unexpected turns as the world drifted toward global war.

Back to deakin.edu.au

Friday essay: how archaeology helped save the Franklin River

Billy Griffiths, Deakin University

On 1 July 1983, in a dramatic four-three decision, the High Court of Australia ruled to stop the damming of the Franklin River. It brought an end to a protracted campaign that had helped bring down two state premiers and a prime minister, as well as overseeing the rise of a new figure on the political landscape – the future founder of the Greens, Bob Brown.

Morning Mist Rock Island Bend, Franklin River, Southwest Tasmania. Peter Dombrovskis/ (courtesy Liz Dombrovskis) AAP

The fact that a remote corner of southwest Tasmania became the centre of national debate reflects what was at stake in the campaigns against hydro-electric development. For many, like novelist James McQueen, the Franklin was “ not just a river ”: “it is the epitome of all the lost forests, all the submerged lakes, all the tamed rivers, all the extinguished species”. The campaign was a fight for the survival of “a corner of Australia untouched by man”; it was a fight for the right of “wilderness” to exist.

“It is a wild and wondrous thing,” Bob Brown wrote of the Franklin River in May 1978, “and 175 years after Tasmania’s first European settlement, the Franklin remains much as it was before man – black or white – came to its precincts.”

But it was not only the idea of “wilderness” – of an ancient, pure, timeless landscape – that saved the Franklin. The archaeological research that took place during the campaign was at the heart of the High Court decision. Far from being untouched and pristine, southwest Tasmania had a deep human history. What was undoubtedly a natural wonder was also a cultural landscape.

‘A sea of stone artefacts’

The archaeological site at the centre of the campaign was, for a time, known by two names: Fraser Cave and Kutikina. Kevin Kiernan, a caver and the first director of the Tasmanian Wilderness Society, was the first to rediscover the site. He and Greg Middleton recorded it on 13 January 1977 as part of a systematic survey of the lower and middle Gordon and Franklin Rivers.

They were aware that the monolithic Hydro-Electric Commission was considering the region as the site for a new dam and they were searching for something – “maybe a big whizz-bang cave” – that might save these valleys from being flooded. In an attempt to raise awareness of this threatened landscape, they started a tradition of naming rock features in the southwest “after the political figures who would decide their fate”.

Fraser Cave was thus named after the sitting Prime Minister, Malcolm Fraser. There was also a Whitlam cave, a Hayden Cave and a Bingham Arch. When the Tasmanian Nomenclature Board caught wind of this tradition, they accused Kiernan and other members of the Sydney Speleological Society of “gross impertinence” for naming caves outside their state. In mid-1982, at the suggestion of the Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre, Fraser Cave became Kutikina, which means “spirit” in the oral tradition nurtured by the dispossessed Tasmanian Aboriginal community on Babel Island in Bass Strait.

The excavations at Kutikina played a powerful political role in the Franklin River campaign. Rhys Jones, AIATSIS, JONES.R09.CS.000142949

But although Kiernan admired the natural splendour of Kutikina in 1977, he did not immediately recognise the artefacts it contained as human-made. It was not until he returned in February 1981 that he realised what he had found. He and the new director of the Tasmanian Wilderness Society, Bob Brown, and its secretary, Bob Burton, were searching the remote valley for evidence of a convict who had supposedly perished in the region after escaping the Macquarie Harbour Penal Station.

The story conjured the “wildness” of the country and the discovery of his bones might help bring publicity to their campaign against the dam. But when they climbed through the entrance of Kutikina, they were amazed to find a sea of stone artefacts and ashy hearths extending into the dark. These were no convict bones.

Three weeks later, a team of archaeologists, cavers and National Parks officers rafted down the Franklin River to investigate. It was already dark on 9 March 1981 when they tied their boats to the riverbank. They had a deep chill after hours navigating the fast-flowing river, hauling their aluminium punt and rubber dingy over successive rapids, journeying deeper into the dense rainforest. The rain picked up again as they unloaded their gear and took shelter in the mouth of the cave, which opened “like a huge, curved shell”.

Some of the team started a small, smoky fire to cook their dinner, while the others, with the light of their torches, ventured into the cavern. Kutikina opened out “like an aircraft hangar” and extended for almost 200 metres into the cliff. But it was not its scale that excited them: it was the idea that this remote cave, buried in thick “horizontal” rainforest, could have once been home to a thriving human population.

Too tired to erect their tents, they unrolled their sleeping mats on the disturbed floor at the cave entrance. It later occurred to them that they were probably the first people to sleep there in around 15,000 years.

Over the following days, as rain poured outside, the team carefully surveyed Kutikina. The archaeologists, Rhys Jones and Don Ranson, opened a small trench where the black sediment of the floor was covered by a thin layer of soft stalagmite. The test pit only extended to a depth of 1.2 metres before it met bedrock, but it yielded an extraordinary 75,000 artefacts and 250,000 animal bone fragments.

Don Ranson outside Kutikina in the heart of the southwest Tasmanian rainforest. Rhys Jones, AIATSIS, JONES.R09.CS.000142944

This small pit represented about one per cent of the artefact-bearing deposit, making the cave one of the richest archaeological sites in Australia. “In terms of the number of stone tools,” Jones said to one journalist, “much, much richer than Mungo.”

The archaeological remains at Kutikina told a remarkable story. The tools appeared to be a regional variant of the “Australian core tool and scraper tradition”, found across the mainland during the Pleistocene, suggesting immense chains of cultural connection before the creation of Bass Strait. The bone fragments were also curious. Most had been charred or smashed to extract marrow, and almost all (95 per cent) were wallaby bones, suggesting a finely targeted hunting strategy, similar to that found in the Dordogne region in France.

But most surprisingly, underneath the upper layer of hearths, there were angular fragments of limestone that appeared to have shattered and fallen from the cave roof at a time of extreme cold, forming rubble on the floor. It was one of the main pieces of evidence that led Jones to speculate in his diary: “Is this the late glacial technology?”

Home to the southernmost humans on earth

The possibility of Ice Age dates conjured the image of a dramatically different world. Pollen records in the region revealed that what is now rainforest was once an alpine herbfield like the tundra found in Alaska, northern Russia and northern Canada. Twenty thousand years ago, the mighty trees of ancient Gondwanaland had retreated to the river gorges, where they were irrigated and sheltered from fire, while wallabies and wombats roamed the high, open plains above.

The cold blast of Antarctica, only 1000 kilometres to the south, had dropped temperatures by around 6.5 degrees Celsius. A 65-square-kilometre ice cap presided over the central Tasmanian plateau, feeding a 12-kilometre-long glacier that gripped the upper Franklin valley. Icebergs floated off the Tasmanian coast.

At the height of the last Ice Age, Kutikina was home to the southernmost humans on earth. The people of southwest Tasmania hunted red-necked wallabies on the broad open slopes of Franklin valley, they collected fine stone from glacial melt water gravels and chipped them into tools, and they sheltered beside fires in the mouths of deep, limestone caverns. “They alone,” Jones reflected, “may have experienced the high latitude, glacier-edge conditions of a southern Ice Age.”

Significantly, during a separate excavation near the confluence of the Denison and Gordon Rivers, archaeologists also discovered tools and charcoal dating to 250–450 years ago, long after the ice cap had melted and the rainforest had returned. It revealed that the river valleys of southwest Tasmania had a recent, as well as a deep, Aboriginal history.

The rediscovery of Kutikina made the front page of the local and national newspapers, and was discussed on the floor of Parliament, but, surprisingly, it was restricted to the margins of the conservation campaign. John Mulvaney later reflected on the productive, albeit tense alliance between archaeologists and conservationists during the campaign:

We claimed an Ice Age environment of tundra-like grasslands, where their dearly loved primeval forest was supposed to have stood eternally. By discrediting the image of a forest wilderness, we were ruining their image and battle cry!

Added to this tension was the animosity the Tasmanian Aboriginal community felt towards both the archaeologists, for fossicking on their land, and the conservationists, for suggesting they had never lived there. Their activism during the campaign had profound implications for the Australian archaeological community. But while Aboriginal leaders such as Rosalind Langford and Michael Mansell were eager to regain control of Kutikina – “the most sacred thing in the state” – they also recognised the value of the history that had been uncovered. As Mansell said:

The fact that the Aborigines could survive physically and culturally in adverse conditions and over such a long period of time … helps me counteract the feeling of racial inferiority and enables me to demonstrate within the wider community that I and my people are the equal of other members of the community.

At the 1981 Tasmanian Power Referendum, 47 per cent of the electorate voted in favour of the Gordon-below-Franklin dam. But, remarkably, there was also a 45 per cent informal vote. Tens of thousands of voters had scrawled “no dams” on their ballot papers. The unprecedented “write-in” had been organised by the Tasmanian Wilderness Society, led by Brown. It repeated this highly organised, campaign-oriented strategy at local, state and federal elections throughout 1982.

The federal leader of the Australian Democrats, Don Chipp, also recognised the mood of the electorate against the dam and in August 1981 he initiated a Senate inquiry into “the federal responsibility in assisting Tasmania to preserve its wilderness areas of national and international importance”. Jones, Mulvaney and the executive of the Australian Archaeological Association were among the many to make submissions to the new Senate Select Committee.

The Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre also made a submission, drawing upon the archaeological research to underline the cave’s “great historical importance”. But they also made a more personal plea. The Franklin River caves “form part of us – we are of them and they of us. Their destruction represents a part destruction of us.”

This advocacy had a profound influence. Several members of the Senate Committee flew into the Franklin valley to see the ongoing archaeological work and when the committee presented its report on the Future Demand and Supply of Electricity for Tasmania and Other Matters, the archaeology dominated the “other matters”. “Apart from any other reasons for preserving the area,” they concluded, “the caves are of such importance that the Franklin River be not inundated.”

Prime Minister Fraser heeded the conclusions of the report. He did not want the Franklin dam built, but he was reluctant to intervene in what he regarded as a state matter. So he did not act when construction on the dam began in July 1982.

Protests and political shifts

On 14 December 1982, the same day the region was formally listed as a World Heritage site for its natural and cultural value, a chain of rubber rafts blocked the main landing sites along the Franklin River, protestors occupied the dam site and rallies were held in cities across Australia.

Anti-dam protesters in southwest Tasmania, opposing the planned construction of the Franklin River dam, 1982. National Archives of Australia

By autumn 1983, 1272 protestors had been arrested during the Franklin blockade, and nearly 450 had done time in Hobart’s Risdon Prison, including Mansell and Langford, who were charged with trespass on their return from visiting Kutikina.

While the blockade continued, and with a federal election just around the corner, the ALP made a snap change in its leadership on 3 February 1983. It replaced Bill Hayden, who had voted against Labor’s policy to stop the dam at the party’s national conference, with Bob Hawke, who had voted for it. And in a tumultuous few hours of Australian political history, Fraser called an early election on the same day. It would turn out to be a grievous political miscalculation.

Neither Fraser nor Hawke believed the Franklin River dispute decided the 5 March 1983 election, but the outgoing Deputy Prime Minister, Doug Anthony, was adamant: “There is no doubt that the dam was the issue that lost the government the election.”

On 31 March the new Hawke government passed regulations to prevent further construction on the Franklin dam. Tasmanian Premier Robin Gray took the matter to the High Court, challenging the constitutionality of Hawke’s “interventionist” legislation. His appeal failed by the narrowest of margins.

The judges in the majority considered that the Commonwealth had a clear obligation to use its External Affairs power to stop the proposed dam, as the inundation of “the Franklin River, including Kutikina Cave and Deena Reena Cave”, would breach the World Heritage Properties Conservation Act and damage Australia’s international standing. They also invoked the Commonwealth power to make laws with respect to Aboriginal people.

The Franklin River campaign has entered “the folklore of Australian environmentalism” as a green victory: a battle won, in Clive Hamilton’s words, through “ the intrinsic worth of wild places .” But behind the scenes it was the deep Aboriginal history of the region that pushed the decision over the line. The archaeological evidence featured in every report about the judgement, and privately Malcolm Fraser considered it to be the deciding factor.

This is an edited extract from Billy Griffiths’ Deep Time Dreaming: Uncovering Ancient Australia (Black Inc., 2018).

Billy Griffiths , Research fellow, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article .

Looking to partner with Australia's leading social sciences and humanities research institute?

If you are interested in partnering or studying with us – we're keen to hear from you.

Read The Diplomat , Know The Asia-Pacific

- Central Asia

- Southeast Asia

- Environment

- Asia Defense

- China Power

Crossroads Asia

- Flashpoints

- Pacific Money

- Tokyo Report

- Trans-Pacific View

- Photo Essays

- Write for Us

- Subscriptions

Between Russia and China, the Black Dragon River

Recent features.

The Domestic Politics Behind Inter-Korean Relations

Amin Saikal on the United States’ Many Mistakes in Afghanistan

Why the Nuclear Revolution Matters in an Era of Emerging Great Power Competition

Sri Lanka’s Central Asia Gambit

The Curious Vatican-Asian Alliance

Donald Trump’s China Rhetoric Has Changed. The Epoch Times’ Support For Him Has Not.

Imran Khan’s Biggest Trial

Seoul Is Importing Domestic Workers From the Philippines

The Rise, Decline, and Possible Resurrection of China’s Confucius Institutes

Nowhere to Go: Myanmar’s Exiled Journalists in Thailand

Trump 2.0 Would Get Mixed Responses in the Indo-Pacific

Why Thaksin Could Help Hasten a Middle-Class Revolution in Thailand

The Amur River separates China from Russia’s Far East, and not so long ago was the site of bloody conflict.

In 1900, as the Boxer Rebellion seared Beijing, officials hundreds of miles northward came to a decision. Community leaders in Blagoveshchensk, a Russian metropole along the Amur River – that great, gurgling run dividing southeastern Russia from northeastern China – found themselves rattled, rocked by the anti-Western forces suddenly rippling through China. As such, local leaders began gathering the Chinese residents throughout their city, some four or five thousand in all, in an attempt to expel anyone they thought may pose a risk to local stability. Led by contingents of Amur Cossacks, the Russian denizens of Blagoveshchensk rounded up thousands of ethnic Chinese to push back across the border – back across the Amur, the ninth-largest river in the world.

The other side, of course, was too far for a simple swim. The first into the water, caught in the current, drowned. The others attempted to plead, or to flee, to no avail. Soon the Cossacks were joined by old men and children alike, gunning or axing down those who refused to swim across. As Dominic Ziegler, The Economist ’s Asia editor, recounts in Black Dragon River , his masterful examination of the Amur River’s bloodied history, “No more than one hundred reached the other shore. It was not, the official note stated, a crossing ‘but an extermination.”’

A century later, relations between Beijing and Moscow have recovered, expedited by the Kremlin’s recent and growing distance from Brussels and Washington. But as Ziegler’s narrative – stretching from the Golden Horde to post-Mao marketization – threads, there’s a facile reality, a false contentedness, between the two. Moscow and Beijing may be, as Chinese officials hope , “friends forever,” but scratch a bit further and a lingering animus bubbles up, spilling over the Amur.

To be sure, Ziegler’s work does not center solely on the centuries-long dance of rotating governments in Moscow and Beijing. If anything, some of the most commendable sections come when Ziegler shifts his focus to the local populations: the diminished Daurians, the neglected Nivkh, communities too often elided in sweeping Siberian histories, but treated as co-equals in Ziegler’s narrative, much as they were in Bruce Lincoln’s magisterial The Conquest of a Continent . (As Ziegler confirms, “The narrative of the European conquest and settlement of new lands comes everywhere now with acknowledgment of guilt and open shows of contrition. Except in the Russian Far East.”)

But it is the broader Beijing-Moscow relations, and histories, that will interest English-speaking readers. To wit, Ziegler brings his gaze — and his lush language, as vertiginous as the river basin he describes — to detailing 1689’s Treaty of Nerchinsk, China’s first treaty with a European power. The treaty, we’re told, brought with it “a subliminal sense that this first treaty was one negotiated on a basis of equality,” one that “tempers relations between the two powers to this day.” But Ziegler reminds us that Moscow’s 19th-century expansionism wasn’t limited to Wallachia or Bukhara, but stretched to the broader Amur basin, with Russia’s imperial entrepreneurs grabbing swaths at will from a prone Beijing.

Such rote annexation led eventually to the bloodletting in Blagoveshchensk – and, a few decades on, to a spike in nuclearized tensions along the Ussuri tributary. Such strain, buffeted by Maoist paranoia and pre-communist land-claims, culminated in 1969’s Damansky Incident, with dozens of casualties, and potentially far more, littering both sides of the nominally fraternal nations. While tensions have since thawed between the two, members of the Communist Party of China nonetheless refer sotto voce to the Amur regions as “historically Chinese possessions.”

The Amur, meanwhile, pushes on, bracing a boundary that remains largely stable. But with the Kremlin’s post-2014 precedent for redrawing state lines at will, there’s no guarantee that the Amur’s bloodstained border will remain permanent, or desired. As Ziegler notes, “If Russia can tear up agreements and treaties to grab Crimea, what kind of an example does that set for an increasingly assertive China that might one day awake to feel longings for its former lands beyond the Amur?”

After all, the Blagoveshchensk events were a century ago for men, but only a few moments in the broad sweep that is the Amur’s history.

Sino-Russian Economic Cooperation in Central Asia is Not What It Seems to Be

By varshini sridhar.

Can Russia and China 'Synergize' the Eurasian Economic Union and the Belt and Road Initiative?

By catherine putz.

China Quietly Looms Over Zapad 2017 Exercises

By nicholas trickett.

China and Russia in Central Asia: Rivalries and Resonance

Indian-Built Russian Su-30 Fighter Could Soon Be a Game Changer on Export Markets

By a.b. abrams.

By Haeyoon Kim

By Si-yuan Li and Kenneth King

Captured Myanmar Soldier: Army Joined Hands With ARSA Against Arakan Army Advance

By rajeev bhattacharyya.

By Alex Alfirraz Scheers

By Uditha Devapriya

By Victor Gaetan

By Bryanna Entwistle

Chapter 13 Introductory Essay: 1945-1960

Written by: patrick allitt, emory university, by the end of this section, you will:.

- Explain the context for societal change from 1945 to 1960

- Explain the extent to which the events of the period from 1945 to 1960 reshaped national identity

Introduction

World War II ended in 1945. The United States and the Soviet Union had cooperated to defeat Nazi Germany, but they mistrusted each other. Joseph Stalin, the Soviet dictator, believed the Americans had waited too long before launching the D-Day invasion of France in 1944, leaving his people to bear the full brunt of the German war machine. It was true that Soviet casualties were more than 20 million, whereas American casualties in all theaters of war were fewer than half a million.

On the other hand, Harry Truman, Franklin Roosevelt’s vice president, who had become president after Roosevelt’s death in April 1945, believed Stalin had betrayed a promise made to Roosevelt at the Yalta summit in February 1945. That promise was to permit all the nations of Europe to become independent and self-governing at the war’s end. Instead, Stalin installed Soviet puppet governments in Poland, East Germany, Czechoslovakia, Rumania, Hungary, and Bulgaria, the parts of Europe his armies had recaptured from the Nazis.

These tensions between the two countries set the stage for the Cold War that came to dominate foreign and domestic policy during the postwar era. The world’s two superpowers turned from allies into ideological and strategic enemies as they struggled to protect and spread their systems around the world, while at the same time developing arsenals of nuclear weapons that could destroy it. Domestically, the United States emerged from the war as the world’s unchallenged economic powerhouse and enjoyed great prosperity from pent-up consumer demand and industrial dominance. Americans generally supported preserving the New Deal welfare state and the postwar anti-communist crusade. While millions of white middle-class Americans moved to settle down in the suburbs, African Americans had fought a war against racism abroad and were prepared to challenge it at home.

The Truman Doctrine and the Cold War

Journalists nicknamed the deteriorating relationship between the two great powers a “ cold war ,” and the name stuck. In the short run, America possessed the great advantage of being the only possessor of nuclear weapons as a result of the Manhattan Project. It had used two of them against the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki to end the war in the Far East, with destructive power so fearsome it deterred Soviet aggression. But after nearly four years of war, Truman was reluctant to risk a future conflict. Instead, with congressional support, he pledged to keep American forces in Europe to prevent any more Soviet advances. This was the “ Truman Doctrine ,” a dramatic contrast with the American decision after World War I to withdraw from European affairs. (See the Harry S. Truman, “Truman Doctrine” Address, March 1947 Primary Source.)

President Harry Truman pictured here in his official presidential portrait pledged to counter Soviet geopolitical expansion with his “Truman Doctrine.”

The National Security Act, passed by Congress in 1947, reorganized the relationship between the military forces and the government. It created the National Security Council (NSC), the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), and the office of Secretary of Defense. The Air Force, previously a branch of the U.S. Army, now became independent, a reflection of its new importance in an era of nuclear weapons. Eventually, NSC-68, a secret memorandum from 1950, was used to authorize large increases in American military strength and aid to its allies, aiming to ensure a high degree of readiness for war against the Soviet Union.