Writing-to-Learn Activities

Getting Started

Why include writing in my courses?

What is writing to learn?

WTL Activities

What is writing to engage?

What is writing in the disciplines?

WID Assignments

Useful Knowledge

What should I know about rhetorical situations?

Do I have to be an expert in grammar to assign writing?

What should I know about genre and design?

What should I know about second-language writing?

What teaching resources are available?

What should I know about WAC and graduate education?

Assigning Writing

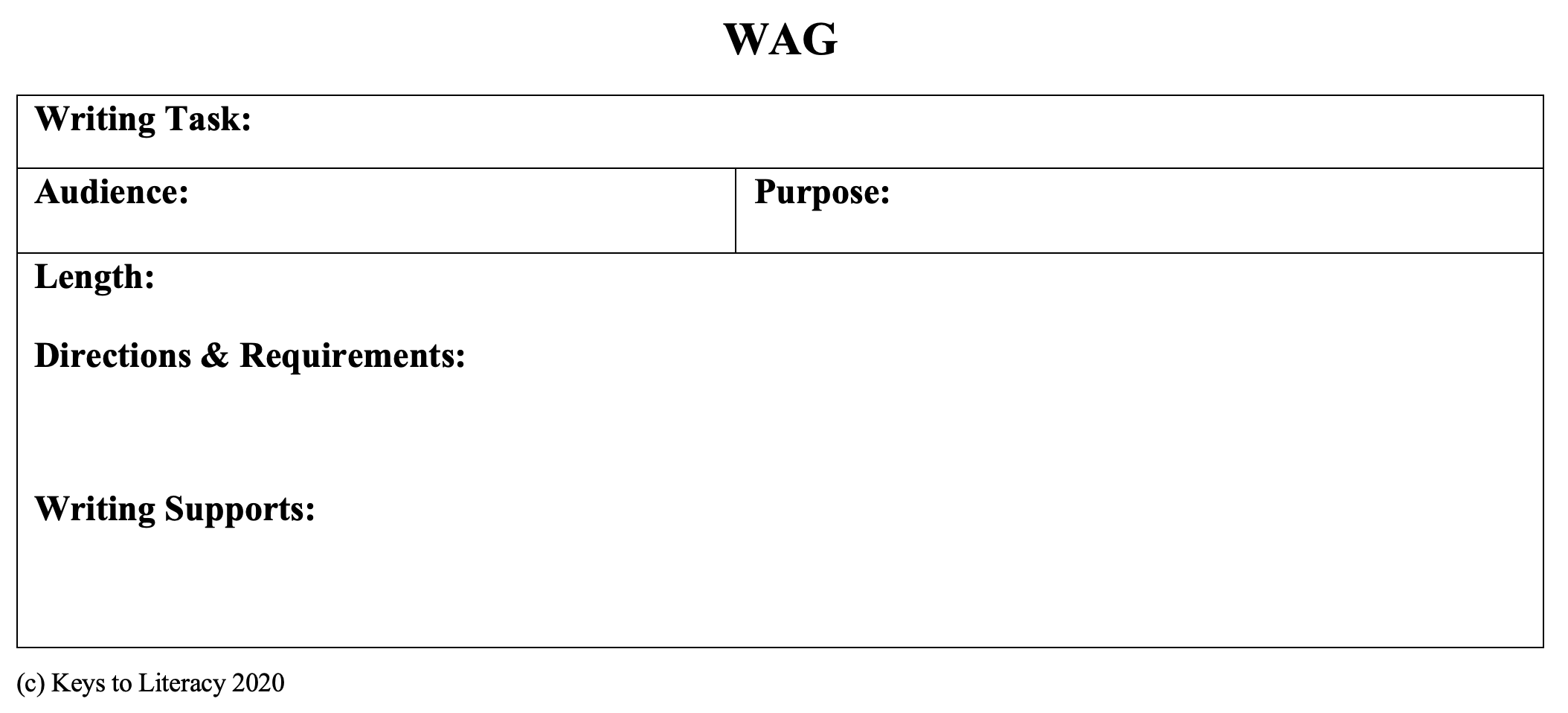

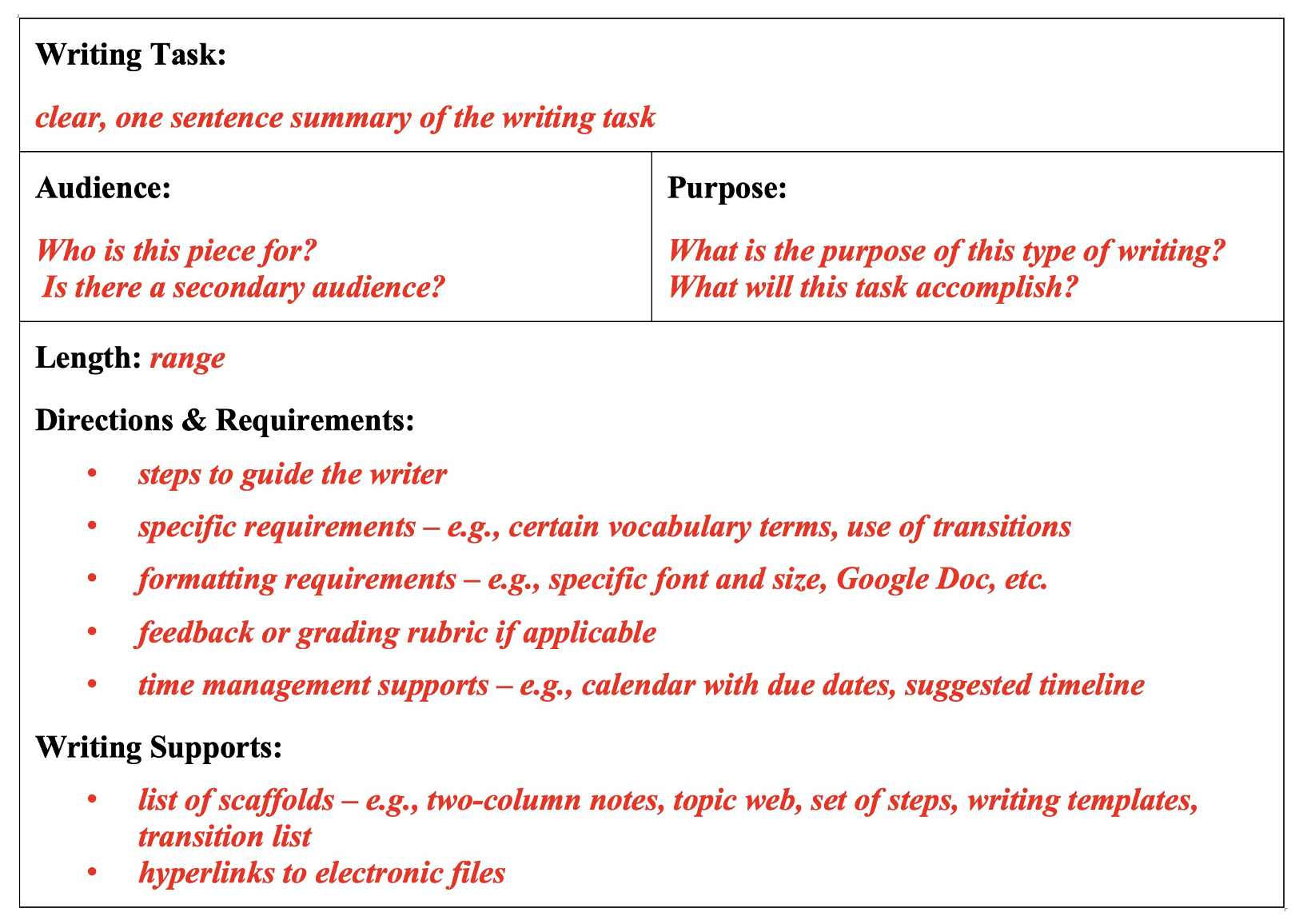

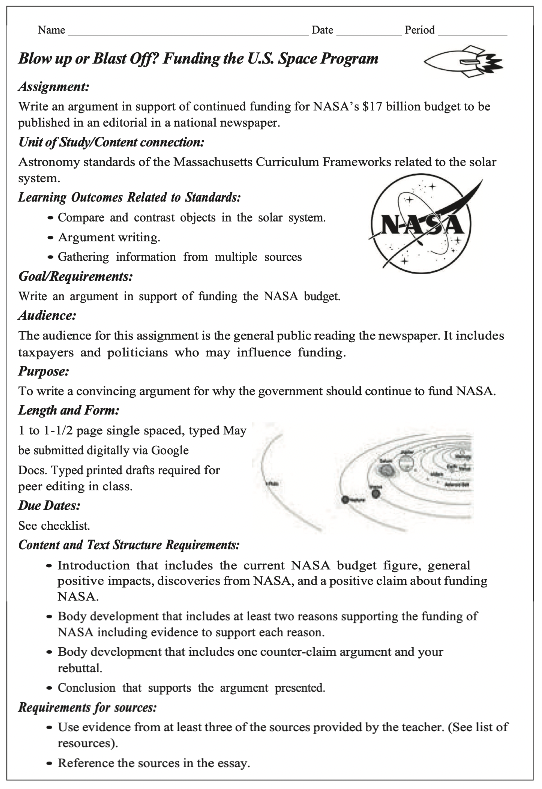

What makes a good writing assignment?

How can I avoid getting lousy student writing?

What benefits might reflective writing have for my students?

Using Peer Review

Why consider collaborative writing assignments?

Do writing and peer review take up too much class time?

How can I get the most out of peer review?

Responding to Writing

How can I handle responding to student writing?

How can writing centers support writing in my courses?

What writing resources are available for my students?

Using Technology

How can computer technologies support writing in my classes?

Designing and Assessing WAC Programs

What is a WAC program?

What designs are typical for WAC programs?

How can WAC programs be assessed?

More on WAC

Where can I learn more about WAC?

Writing-to-learn activities can happen frequently or infrequently in your class; some can extend over the entire semester; some can be extended to include a wide variety of writing tasks in different formats and to different audiences. Use the list below to read more about writing-to-learn activities.

- The reading journal

- Generic and focused summaries

Annotations

- Response papers

- Synthesis papers

- The discussion starter

- Focusing a discussion

- The learning log

- Analyzing the process

- Problem statement

- Solving real problems

- Pre-test warm-ups

Using Cases

- What counts as a fact?

- Believing and doubting game

- Analysis of events

- Project notebooks

- The writing journal

The Reading Journal

Some teachers combine the learning log and the reading journal, but others prefer to keep them separate, particularly when the daily outside reading is crucial to a class. The reading journal provides students with at least two kinds of critical thinking activities that promote learning.

How Do Reading Journals Promote Learning?

In general, students use the left half of the page or the left sheet of an opened notebook for recording what the reading is about. Teachers can ask for quite a lot of detail in this half of the reading journal so that students get practice in summarizing entire articles or summarizing particular arguments, identifying main ideas, noting key details, and choosing pertinent quotations, among other crucial reading skills.

On the right half of the page (or right page of the notebook), students jot down any questions they have or any connections they can make between readings or between readings and class discussions. At the beginning of the semester, the right half of the journal is dotted with questions, most of which can be answered quickly at the beginning of a discussion session in class. By the end of the semester, students will sometimes fill two right-hand columns for every reading. At this point, the questions are far richer (rarely about content) and the connections point out that students are integrating the readings and class work on their own.

In addition, reading journals have the following benefits:

- Writing about reading makes students more conscious of making meaning as readers (and gives them insight into reading and writing processes).

- Writing about reading gives them their own texts to re-read and reflect on, which sparks fuller learning.

- Writing about reading, writing, and discussing forces students to take charge of their learning and to make active connections between different learning activities.

- Seeing teachers write in their own reading journals and share their writing reinforces for students the vital importance of writing for life-long learning and emphasizes the public nature of these journals.

- Students often discover their own paper topics in the connections that keep appearing in the right-hand section of these notebooks.

- As students get more used to writing about their understanding of the literal level of meaning, they also become better at generating higher-level questions and connections--especially connections between and inferences from text materials or discussions.

- Even less prepared students who don't get to higher order questioning will at least know what they don't know so that you can work with them on their basic understanding of text. (In other words, when you ask for questions at the beginning of your work on a piece of reading, students know what to ask.)

What Kinds of Course Readings Will Work in a Reading Journal?

Teachers can use the same format for any kind of reading, even asking for more formal summaries if that is appropriate for the sequence of assignments or the course goals. Possible readings include professional or student essays, news articles, materials turned up during research for a longer assignment, textbook readings.

And the same format will work for any other kind of observation that you want students to reflect on:

- TV programs

- Class discussions

- Prior writing assignments

Content Questions: More Detail

The structure of the daily writing depends on the students'

- Lower-level students will need more structure and will move more slowly into analytic and reflective writing on the right-hand side.

- Higher-level students can sometimes whisk right into reflection with much less attention and structure imposed for literal information.

The structure also depends on the particular reading/writing tasks, especially if you are building a sequence of tasks leading to a substantial writing assignment at the end of a unit, for example.

Obviously, teachers can assign specific questions to be addressed in the left-hand section, or assign more general prompts:

- What do you remember?

- What did you hear?

- What was the "talk" about?

- Who is the focus of the reading?

- What was the most important idea in the reading? What are the next important ideas?

- What particularly striking example do you recall?

- Who is the target audience for the selection?

- What is the author's intention in this passage?

These prompts will focus on what because they are getting at the basic content (though we must remember that content is constructed and so even literal information may not appear the same to each reader/writer/speaker).

Interpretive Questions: More Detail

Students often need more focused questions to begin working on the right-hand side--the evaluative, reflective, or metacognitive side:

- Why are certain details more memorable?

- What connections can you make between X and Y?

- How did you arrive at this conclusion?

- Why is this conclusion significant?

- How does this assignment touch you personally?

- How does this assignment change your thinking on the idea?

- How could you write about your new insight?

- What other information might you need to pursue this topic?

- How does this reading/writing/discussion/group work build on our earlier discussion of the larger concept of X?

Generic and Focused Summaries

Depending on the level of detail that might be useful for each assignment, have students write out a paragraph or a page of summary for each assigned reading. When collected in a reading journal or learning log, these summaries help students understand readings more fully when they are first assigned and remember them clearly for later tests or synthesis assignments.

You might also consider asking students to do more focused summaries. By providing key questions about the reading, you can help students narrow in on the main ideas you want them to emphasize and remember from a reading.

Or if abstracts are significant in your discipline, you might ask students to analyze the abstracts in a major professional journal and write similar abstracts of the readings they are assigned in the course.

Unlike the summary that attempts an objective rendering of the key points in a reading, an annotation typically asks students to note key ideas and briefly evaluate strengths and weaknesses in an article. In particular, annotations often ask students to note the purpose and scope of a reading and to relate the reading to a particular course project.

You can have students annotate (and eventually compare) readings assigned for the class, or you can ask students to compile annotations to supplement the course readings. Each student's annotations can be distributed to the class in one handout or through electronic media (Web forum, e mail).

Response Assignments

Still another type of writing to learn that builds on assigned readings is the response paper. Unlike the summary, the response paper specifically asks students to react to assigned readings. Students might write responses that analyze specified features of a reading (the quality of data, the focus of research reported, the validity of research design, the effectiveness of logical argument). Or they might write counter-arguments.

To extend these response papers (which can be any length the instructor sets), consider combining them into another assignment—a position paper or a research-based writing assignment.

Synthesis Assignments

A more complex response to assigned readings is the synthesis paper. Rather than summarizing or responding to a single reading assignment, the synthesis paper asks students to work with several readings and to draw commonalities out of those readings. Particularly when individual readings over-simplify a topic or perspectives on a question in your course, the synthesis paper guarantees that students grapple with the complexity of issues and ideas.

Like other writing-to-learn tasks, the synthesis paper can be shorter and less formal, or you can assign it at or near the end of a sequence leading to a more formal assignment.

The Discussion Starter

Sometimes students feel baffled by a reading assignment and express that frustration in class, but they often understand more about the reading than they believe they do. When this situation arises, having students write about the reading can be especially valuable, both for clarifying what students do and don't understand and for focusing students' attention on key points in the reading.

If you know a particular reading assignment is likely to give students trouble, you might plan questions in advance. But even if students' frustration catches you by surprise, you can easily ask questions about the key issues or points in the article. Moreover, asking students to answer the same questions again at the end of the class, after you've had a chance to discuss the reading, will help you see what students still don't understand.

Focusing a Discussion

When a discussion seems to be taking off in several directions, dominated by just a few students, or emotionally charged, stop the discussion and ask students to write either what they saw as the main threads of the discussion or where the discussion might most profitably go. After writing for a few minutes, students will often be better able to identify and stay on productive tracks of discussion. Or, after asking a few students to read their writing aloud, the teacher can decide how best to redirect the discussion.

The Learning Log

The learning log serves many of the functions of an ongoing laboratory notebook. During most class sessions, students write for about five minutes, often summarizing the class lecture material, noting the key points of a lab session, raising unanswered questions from a preceding class. Sometimes, students write for just one or two minutes both at the beginning and end of a class session. At the beginning, they might summarize the key points from the preceding class (so that the teacher doesn't have to remind them about the previous day's class). At the end of class students might write briefly about a question such as:

- What one idea that we talked about today most interested you and why?

- What was the clearest point we made today? What was the foggiest point?

- What do you still not understand about the concept we've been discussing?

- If you had to restate the concept in your own terms, how would you do that?

- How does today's discussion build on yesterday's?

Such questions can provide continuity from class to class, but they can also give teachers a quick glimpse into how well the class materials are getting across. Some teachers pick up the complete learning logs every other week to skim through them, and others pick up a single response, particularly after introducing a key concept. These occasional snapshots of students comprehension help teachers quickly gauge just how well students understand the material. Teachers can then tailor the following class to clarify and elaborate most helpfully for students.

Analyzing the Process

Sometimes students are baffled by the explanations teachers give of how things happen because teachers move too quickly or easily through the process analysis. A quick run-through of an equation is often just not enough for students struggling to learn new material.

A more useful approach to process analysis—from the learners' point of view—is to trace in writing the steps required to complete the process or to capture the thinking that leads from one step to the next. Students can either write while or after they complete each problem. Particularly when students get stuck in the middle of a problem, writing down why they completed the steps they did will usually help someone else (a classmate, tutor, or teacher) see why the student experienced a glitch in problem-solving. Similarly, teachers can look over the process analyses to see if students have misapplied fundamental principles or if they are making simple mistakes. In effect, students can concentrate on problem-solving rather than on minor details, and they can move from simple procedures followed by rote into a deeper understanding of why they are solving problems appropriately.

The Problem Statement

Teachers usually set up the problems and ask students to provide solutions. Two alternatives to this standard procedure will give students practice with both framing and solving problems:

- After you introduce a new concept in your course, ask students to write out a theoretical or practical problem that the concept might help to solve. Students can exchange these problems and write out solutions, thus ensuring that they understand the concept clearly and fully.

- Ask students to write out problem statements before they come to your office hours for conference. (Or you might suggest that they use e mail to send you these problem statements in lieu of a face-to-face conference.) Students are likely to frame such a problem more concretely than they might otherwise do in preparing for a conference, and the resulting conference (or e-mail exchange) is likely to be more productive for both student and teacher.

Another version of this exercise is to have students write a problem statement that is passed on to another student whose job it is to answer it. Such peer answers are especially useful in large classes.

Solving Real Problems

Ask individuals or groups to analyze a real problem—gleaned from industry reports, scientific journals, personal experience, management practices, law, etc. Students must write about the problem and a solution they could implement.

Pre-Test Warm-ups

Another extension of the problem statement WTL activity is to ask students to generate problems for an upcoming test. Students might work collaboratively either to generate problems or to draft solutions. By asking each student or group of students to generate problems, students will cover the course material more fully than they might otherwise do in studying. Moreover, if you assure students that at least some of the test material will draw on the problems students generate, they are more likely to take both the problems and solutions more seriously. Furthermore, if students don't understand the material, they will surely find out as they write questions for the exams!

Another alternative for pre-test warm up writing is to give out sample test questions in advance of the exam. Students can work individually or in groups to write out responses. Again, because they know some of the test material will come from the WTL activity, students are likely to prepare more carefully.

Because cases provide students with a complete writing context, they can be exceptionally useful for student writers.

A simple use of the case is to set up a single scenario which notes the audience, purpose, and focus of a brief writing task. For example, a business student might encounter this scenario:

Assume that you've just been hired in a local office of a large asset management firm. Your first client has traded stocks conservatively for several years and now wants to try options trading. What basic principles of options trading do you need to be sure your client understands?

A teacher could assign this scenario and ask for a variety of writing tasks in response to it:

- Outline the principles in three minutes at the start of class to review the reading from last night.

- Write an e-mail message to your manager to brief her on your plans for educating your client.

- As a final exam response, explain both the principles of options trading and your ethical obligations to your client.

- Generate a working list of principles in a group

- of four students and then find a dozen sources from the library to annotate for their usefulness to the new employee. Compile the most useful annotations from your group to distribute to the entire class.

A more elaborate case can include both more details for the student writer, as well as a wider range of roles to write from. A full case can call for multiple kinds of writing, drawing on the full range of informal and formal writing outlined in this guide. It can also emphasize the kinds of questions (and writing) most common in the discipline, and full-scale cases work well with both individual and collaborative writing assignments.

Finally, case histories are useful in many disciplines and writing contexts. This use of a case generally focuses on a post hoc analysis, either of what happened in the case or what could have happened with different interventions. Again, case histories can lead to a range of writing assignments, though they tend to restrict the roles students might play as writers within the case context.

Students can write to explain professional concepts, positions, or policies in letters of application or letters to politicians.

Students can also write business letters of introduction and research gathering, introducing their projects and plans for approval. Another version of an introductory letter could have students try to persuade an interested party (e.g. a foundation, the NSA, etc.) to provide funding or approval for their research. Or have them write a letter after completing a project which tries to persuade someone interested in the project to accept their recommendations.

What Counts as a Fact?

Select two or more treatments of the same issue, problem, or research. For example, you might bring in an article on a new diet drug from USA Today, The Wall Street Journal, and the Journal of Dietetics . Ask students to write about what constitutes proof or facts in each article and explain why the articles draw on different kinds of evidence, as well as the amount of evidence that supports stated conclusions.

Alternatively, ask students to look at a range of publications within a discipline—trade journals, press releases, scientific reports, first-person narratives, and so on. Have them ask the same kinds of questions about evidence and the range of choices writers make as they develop and support arguments in your field.

The Believing Game and the Doubting Game

First espoused by Peter Elbow, this writing activity simply calls for students to write briefly

- first, in support of an idea, concept, methodology, thesis;

- second, in opposition to it.

As students complete this writing activity based on a course reading or controversy in the field, they become more adept at understanding the complexity of issues and arguments.

Analysis of Events

Although this heading may suggest that only historians can assign this WTL task, in fact an analysis of events can be useful in most fields. This task can take two shapes:

Post hoc analysis: After an event is reported in the general news media or in your disciplinary media, ask students to reflect on

- what happened

- why it happened

- what it means to your field

Various engineering disciplines, for instance, could analyze the Pathfinder mission to Mars by focusing on appropriate elements of the actual event.

What-if analysis: Take an actual event and ask students to write about how the outcome might differ if one crucial condition were changed. For example, what if Dolly, the famous cloned sheep, had been successfully produced on the first try? Students in science disciplines can speculate about scientific elements of this event; students in agriculture courses can focus on the immediate impacts in food production; students in ethics courses could examine the balance of world-wide patterns of food production v. individual identity; students in political science could focus on government funding issues; and so on.

Project Notebooks

Project notebooks have proven to be invaluable in many courses because they capture write-to-learn activities, false starts, and drafts of chunks of a final report on work-in-progress, among other things. Unlike the learning log, which is less likely to include many Writing in the Disciplines (WID) activities, the project notebook can easily combine WTL and WID writing tasks.

Project Notebooks for WTL Activities

In a senior-level engineering design course, students make the following kinds of general write-to-learn entries:

- Process Analysis - As students collect information, build models, and test hypotheses, they record the process they go through in as much detail as possible.

- Problem-solving - When students encounter problems, they write about the problem, possible solutions, and attempted solutions.

- Descriptions - Students record key points from class sessions or conversations with advisors, peers, teachers. Any questions that come up can be recorded in these entries.

- Literature review - When students read printed material on their project topic, they summarize the material fully.

- Pre-conference - Before students meet with advisors or teachers, they organize the questions and issues they plan to discuss in the conference.

- Writing problems or questions

Project Notebooks that Combine WTL and WID Activities

In addition, the project notebook can be used to collect specific writing-to-learn tasks that lead to a final senior project:

First semester

- Audience exercise - describe senior project to freshman in engineering, project advisor, liberal arts graduate.

- Audience exercise - describe target audience for project and explain how audience will affect the project report.

- Draft research question.

- Draft literature review.

- Draft work plan for remainder of semester.

- Draft intro for final draft.

Second semester

- Set writing goals for semester.

- Set research goals for semester.

- Draft methods/results section.

- Paraphrasing exercise.

- Revise intro and lit review.

- Graphics exercise.

- Draft oral presentation.

Project Notebooks: An Instructor Perspective

Among those tasks that have been most valuable is the entry asking students to define a research question and outline research design. Students discovered that they sometimes had less information than they needed about a problem to see how to approach it. Other students found that they needed to do some background reading to ascertain alternative approaches to a research question. Still other students uncovered problems with focus. One instructor told us that his students "had selected a large question that simply could not be answered with the resources and time available to them in a year. This writing activity proved to be one of the most effective in helping students see the role of writing in the planning stages of research design."

View a Writing@CSU Guide

The Writing@CSU Web site provides a writing guide on project notebooks .

The Writing Journal

This variation of the journal or daybook is unlike the learning log or reading journal because it is much more self-directed (although teachers can assign specific journal tasks). Click on the items below to read about more about the writing journal:

Why Keep a Writing Journal?

- Writing more frequently helps students capture ideas--images, sensory details, connections between ideas, comparisons/analogies, etc.

- Writing, reading, and critical thinking are intimately related: we tend to know best the material we write about.

- Writing more frequently helps students think like writers. (Think about the last time you tried to learn a new physical skill--skating, skiing, swimming--and how much more comfortable you got as you simply put yourself repeatedly into the physical environment for that activity.)

What Can Go into a Writing Journal?

Anything can go into a writing journal because it is, quite simply, a collection of everything someone wants to write down. Especially pertinent for students, though, are responses to and questions about readings. Also, encourage students to think of a broad range of questions about what they read--questions about content, style, structure, audience, and so on.

Also students can use journals for other kinds of writing:

- jump starters - snatches of conversation, radio/TV bits, billboards, songs, pictures--jot down anything that strikes you as an interesting image or idea

- experiments--try writing about the same idea to several different audiences ( Ranger Rick, National Wildlife ) or in different genres; try out different analogies to explain a concept

- record of observations--physical or mental

- problem statement and problem solving

- process analysis

- interviews (including conferences with teachers and discussions with peers)

- scenarios or cases (especially good for audience analysis)

- reflections on writing process--questions/problems/successes

Pedagogical Approaches With Canvas

Writing-To-Learn (WTL)

How to Use Writing-To-Learn Impact on Learning Assessment Strategies Writing-To-Learn in Canvas Relevant Technologies Things to Consider Bibliography

Writing-to-learn (WTL) activities are typically short, informal writing assignments that are informational and often assigned at the spur of the moment as an impromptu task. Generally, these are intended to assist students to critically think about important concepts or ideas that are a part of the course content. These writing tasks are frequently limited to less than five minutes of class time or assigned as brief homework assignments. They can be implemented as occasional one-off activities or as regular activities that occur throughout the course.

Depending on your students and discipline, WTL activities might work best as individual-focused: Learners write primarily for themselves to recall, reflect on, and reinforce learning of new information (Boser, 2020). But WTL activities can also be extended by prompting learners to complete a variety of writing tasks in different formats and for different audiences (WAC Clearinghouse, n.d.).

AI writing tools present an interesting gray area for the future of WTL. While tools like automatic spelling and grammar checkers have been accepted as commonplace features of most software that involves any kind of writing, generative AI tools, like ChatGPT and Microsoft Copilot , continue to be used in classroom settings in various and controversial ways (D’Agostino, 2022). Some educators advocate for embracing AI tools as writing aids—particularly if the technology will be part of professional life in students’ chosen disciplines (Stapleton-Corcoran & Horton, 2023).

How to Use Writing-To-Learn

Some of the ways this teaching approach is used to engage students include:

- free writes

- one-minute paper

- one-sentence summaries

- learning logs

- dialectical notes

- directed paraphrasing

- letters, memos, notes

- drafts for peer feedback

- reading journal

- annotations

- response papers

- synthesis papers

- discussion starter

- analyzing the process

- problem statement

- solving real problems

- pretest warm-ups

- using cases

- analysis of events

- project notebooks

Impact on Learning

WTL can impact learning through:

- helping students learn better and retain information longer

- having students think actively about the material they are learning

- prompting students to think at the appropriate cognitive level for the level of learning that is to be accomplished through the course

- encouraging students to define an audience other than the instructor

- developing students’ sensitivity to the interests, backgrounds, and vocabularies of different readers

- giving students the chance to learn about themselves including their emotions, values, cognitive processes, and learning strengths and weaknesses

- showing students what they already know about a topic

- giving students a chance to organize, consolidate, and develop their ideas about a topic

- making clearer to students what they don’t know about a topic, or where they can further improve

Assessment Strategies

WTL activities usually are not graded. Instead, they are quickly read by the instructor or by peers and reviewed for basic understanding of the content being covered.

Suggestions for reviewing WTL activities:

- Use an occasional WTL warm-up at the beginning of class as a “quiz.” Share the correct response and allow students to self-assess their writing.

- Collect completed WTL activities from half a dozen to a dozen students every class or every other class. Briefly review to determine concepts students might need help with.

- In online tools, use stars, “likes,” “praise,” and other positive reinforcement tools to encourage correct responses.

- Ask students to select their best WTL writing for you to review.

- Ask students to share WTL activities with one or two classmates.

- Ask students to post provocative questions or summary/analysis of readings on an electronic bulletin board or web forum for class comment.

Writing-To-Learn in Canvas

In Canvas, the following tools can be used for writing-to-learn activities:

Discussions : Canvas provides an integrated system for asynchronous online class discussions. Instructors and students can start and contribute to discussions. You can learn more about using Discussions in Canvas from the Canvas Community.

Wiki pages : In Canvas, students can complete WTL assignments by creating a page as a wiki and allowing it to be edited by anyone. Students could work on pages individually or in groups, but only one student can edit a page at a time. Instructions for creating a page are available from Canvas.

Relevant Technologies

The following technologies can be used for writing assignments.

Microsoft 365 and Google Workspace : Both sets of online applications include document creation tools that can work offline or online and that allow for collaborative writing and editing as well as sharing with others.

Sites at Penn State : Penn State provides website building and management services to all members of the University community through CampusPress . A site could be created as a shared class blog, or students could create their own sites to use as blogs, journals, galleries, or portfolios.

Viva Engage : A social networking service similar to Facebook but made available as a private tool for Penn State users, Viva Engage can be used for discussions where students can also share files, take polls, give praise, and comment on each other’s posts.

AI writing tools : The Center for the Advancement of Teaching Excellence at the University of Illinois Chicago describes these tools as “…one type of generative AI that can support writing tasks by creating human-like text. These systems work by continually predicting the word most likely to come next in each sentence” (Stapleton-Corcoran & Horton, 2023). Examples include ChatGPT , Microsoft Copilot , and Google Bard as well as many others. Some AI writing tools are trained on specific sets of data to perform specialized tasks: For example, scite was created to assist researchers in discovering and evaluating scientific articles. Penn State has collected a list of AI authoring tools and descriptions .

Things to Consider

For successful implementation of WTL, you should consider the following strategies:

- WTL activities can easily provide a brief classroom assessment to quickly determine what your class is learning while still focusing on the topic. Through this informal formative assessment, instructors can easily diagnose and clarify points of confusion before giving students the next exam and moving on to other topics.

- Reading short, informal writing assignments is no more time-consuming than any other type of class preparation.

While AI writing tools can be incorporated into most WTL activities, for best results, students will need some guidance on how to use AI effectively and ethically. The SPACE framework for writing with AI tools, developed by Glenn Kleiman (2023), and copied below, is one example of how you might approach designing a writing assignment with AI in mind.

Set directions for the goals, content and audience that can be communicated to the AI system. This may, for example, involve writing introductory materials for the overall text and for each section. It could also involve writing much of the text and leaving some sections for AI to complete. Prompt the AI to produce the specific outputs needed. A prompt gives the AI its specific task, and often there will be separate prompts for each section of text. An AI tool can also be prompted to suggest sentences or paragraphs to be embedded in text that is mostly written by the human author. Assess the AI output to validate the information for accuracy, completeness, bias, and writing quality. The results of assessing the generated text will often lead to revising the directions and prompts and having the AI tool generate alternative versions of the text to be used in the next step. Curate the AI-generated text to select what to use and organize it coherently, often working from multiple alternative versions generated by AI along with human written materials. Edit the combined human and AI contributions to the text to produce a well-written document. (Kleiman, 2023)

Bibliography

Boser, U. (2020, June 25). Writing to learn and why it matters. The Learning Curve . https://the-learning-agency-lab.com/the-learning-curve/learn-better-through-writing

Center for Teaching Excellence. (n.d.). Writing to learn . Duquesne University. https://www.duq.edu/about/centers-and-institutes/teaching-and-learning/writing-to-learn

D’Agostino, S. (2022, October 25). Machines can craft essays. How should writing be taught now? Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2022/10/26/machines-can-craft-essays-how-should-writing-be-taught-now

East Carolina University. (n.d.). Writing to learn activities . https://www.ecu.edu/cs-acad/writing/wac/upload/Writing-to-Learn-Activities.pdf

Kleiman, G. (2023, January 5). Teaching students to write with AI: The SPACE framework. Medium . https://medium.com/the-generator/teaching-students-to-write-with-ai-the-space-framework-f10003ec48bc

Kopp, B. (n.d.). Informal writing assignments (writing to learn) . University of Wisconsin–La Crosse. http://www.uwlax.edu/catl/writing/assignments/writingtolearn.htm

McKenna, C. (2019, June 28). Writing for learning. LSE Higher Education Blog . https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/highereducation/2019/06/28/writing-for-learning/

Nilson, L. B. (2010). Writing-to-learn activities and assignments. In Teaching at its best: A research-based resource for college instructors (3rd ed., pp. 167–172). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. https://wp.stolaf.edu/cila/files/2020/09/Teaching-at-Its-Best.pdf

Stapleton-Corcoran, E., & Horton, P. (2023, May 22). AI writing tools . Center for the Advancement of Teaching Excellence, University of Illinois Chicago. https://teaching.uic.edu/ai-writing-tools/

Sweetland Center for Writing. (n.d.). Integrating low-stakes writing in large college classrooms – Supplement 2: Twitter assignments . University of Michigan. https://lsa.umich.edu/content/dam/sweetland-assets/sweetland-documents/teachingresources/IntegratingLowStakesWritingIntoLargeClasses/Supplement2_TwitterAssignments.pdf

WAC Clearinghouse. (n.d.). What is writing to learn? Colorado State University. https://wac.colostate.edu/repository/teaching/intro/wtl/

Writing to Engage

Marvin Diogenes, Director of the Stanford Program in Writing and Rhetoric, explains how low-stakes writing assignments can help students engage with the course materials.

Reading as active meaning-making

We assign readings with the hope that students will find the readings as engaging as we do. We can work toward this outcome by putting active reading in the foreground, inviting students to think explicitly about reading as a creative, meaning-making activity central to their academic work.

Low-stakes, ungraded, and creative writing prompts and activities can improve students’ engagement with and understanding of course readings and other materials, such as videos or podcasts. Such assignments aim to make students more active, purposeful readers, encouraging them to draw on personal experience and past reading experience to engage with new texts (especially unfamiliar or challenging texts).

Writing activities focused on reading move students into a dynamic relationship with the text, helping them engage with texts over time and in relation to each other. Such activities highlight that readings aren’t simply content containers and readers aren’t empty vessels; students create meaning through their active engagement and conversations with others.

Readings aren’t simply content containers and readers aren’t empty vessels; students create meaning through their active engagement and conversations with others.

Start with a reading inventory

When assigning readings, you might begin by asking students about their past reading experiences and current reading strategies. You can also ask students how often their previous teachers asked them to use writing to engage with readings or other course materials.

Gathering reading inventories from your students provides insight into their past reading habits and strategies. A reading inventory activity gets students to consciously reflect on their reading as well and can help you design reading assignments and classroom activities.

You can then take what they share into account when providing specific strategies guiding how you want students to engage with the readings you assign. In particular, use what you learn about them as readers to design writing activities aimed at helping students engage with readings and, as a byproduct, think differently about how they read. Also, keep in mind your learning objectives as you design these activities.

Designing writing-to-engage prompts

Writing-to-engage (also called writing-to-learn) assignments and activities emphasize writing as a key means of learning rather than primarily as a way in which a writer demonstrates mastery of content or knowledge.

This kind of assignment or activity can serve as part of the process of completing a more formal assignment. Often they take the form of freewriting in response to readings, keeping a reading journal for the course, or responding to questions as part of preparing for class discussion of readings.

We can define such writing opportunities as low-stakes (generally not graded other than to note that the student completed the work), creative, and often informed by the writer’s life experience. Writing-to-learn activities move students into a dynamic relationship with course readings and other materials, often through the reading journal, which encourages students to engage with texts over time and in relation to each other. Below you can find examples of various kinds of prompts and activities that you can use or adapt for your classes.

Develop questions to support student engagement

Ask students to respond to questions you prepare to highlight key ideas, concepts, and contexts to guide their reading and help them prepare for class discussion. Develop questions that reflect what you find compelling or engaging about the text. Consider including questions that you don’t have answers for yet.

Ask students to prepare questions about the reading to ask in full class discussion, discuss with a peer or small group, or contribute to a Google document with the rest of the class, generating a list of questions from the full class. You can use the questions in various ways for class activities, such as small group work or clustering questions to highlight key concepts or challenging aspects of the reading.

Ask students to highlight sentences, paragraphs, and sections

Students approaching reading as a process of extraction generally put aside as irrelevant their experience of reading the text. The following prompts emphasize that reading is first of all a human experience (we don’t read as machines). Readers’ prior knowledge, interests, and personal experience shape their engagement with the text and can set the stage for more insightful analytical reading valued in academic settings.

- Write about a favorite sentence or passage (“This for me was the heart of the reading”).

- Write about a sentence or passage that illuminated a new concept, theory, or question (“This taught me something I didn’t know before”).

- Write about a challenging sentence or passage (“Why did this have to be so complicated? Why did this have to be so boring? Why did this have to be so long?”).

- Write about an opaque sentence or passage (“I didn’t understand this at all”).

Ask students to write back to the writer or add to or revise the reading

Students generally don’t think of the writer of their school texts as people trying to engage readers in a relationship through language; thus, they might not think about responding to the invitation of the text with questions or collaboration. The following prompts emphasize that reading provides an avenue to respond directly to the writer and become a collaborator in creating the text as an opportunity for learning.

- Respond directly to the writer of the reading (“This is what I want to ask you/tell you/share with you about what you wrote”).

- Add a sentence, paragraph, or section that the writer left out that you believe would make the text more accessible to readers.

- Revise a sentence, paragraph, or section to make it better/clearer/friendlier/more accessible to readers.

- Develop connections to other texts (“This made me think/think again about what we read earlier in the course”; “This made me think about this other thing I read”) to engage in conversation with the writer.

- Find a personal way into the reading (“This made me think of this in relation to my own experience”) that might expand the writer’s sense of audience and perspective on the topic of the reading.

Ask students to create visualizations and translations

Students generally think of readings as words on a page or screen, perhaps with charts and graphs and works cited listing sources. Asking them to turn prose into visual texts can lead to deeper engagement. Having them create their own versions in visual form or another genre can foster dynamic interactions with readings.

The following prompts offer students opportunities to create visualizations and translate the text in playful, creative ways that might illuminate the meaning and heighten the student’s sense of agency.

- Create a visualization or mapping of the reading. Students might create a map or constellation visualizing the reading in relation to other readings or to their personal experience. .

- Write a review of the reading (this can be creative in terms of the venue for the review, e.g. writing a Yelp review of an academic article).

- Revise the reading for another genre (what if this were the lyrics to a song, a short story, a poem, or a sermon?).

Hume Center for Writing and Speaking resources

- Individual Tutoring Sessions for students

- Class Workshops: Write to PWR Director Marvin Diogenes at [email protected] or Hume Director Zandra Jordan at [email protected]

More News Topics

Studying middle eastern history through graphic novels.

- Instructor Exemplars

Envisioning the future through a sci-fi lens

Dennis sun’s mission to make statistics more relatable.

- Active Learning

- Board of Trustees

- Provost’s Messages to the Drew Community

- Faculty Personnel Policy

- Faculty Personnel Policy – Grievance Procedures (amended)

- President’s Messages to Drew Community

- Honorary Degree Nominations

- President’s Award for Distinguished Teaching

- Strategic Planning

- Drew in a Nutshell

- Mission & History

- Manager Resources

- ADP & College Time Information

- Confidentiality Agreement

- Gender Inequity Agreement

- Employment Opportunities

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Recruitment & Onboarding

- Faculty and Staff Conditions of Employment

- Open Enrollment

- Additional Pay

- Student Employment

- Updating Personal Information

- Wellness Programs

- Faculty/Staff Self-Identification Form

- COVID-19 Faculty/Staff Accommodation Request Form

- The Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center Residency

- Upcoming Events

- Recordings at Drew

- S.W. Bowne Great Hall

- Simon Forum and Athletic Center

- Ehinger Center

- Brothers College

- Drew Forest Preserve

- Special Occasion Photo Requests

- Internal Meetings and Events

- Summer Conferences and Camps

- Meet the Staff

- Make a Payment

- Our Services

- Energy Consumption

- Water Testing Results

- Campus Sustainability

- Our Staff & Contacts

- Mail Services

- Print Services

- The Bookstore

- CLSA Divisional Staff

- Employment & Practical Training

- Important Forms and Policies

- Scope of the Student Conduct Policy

- Community Standards

- Anti-Hazing Policy and Information

- Silent Supporter

- Student Conduct Process

- Conduct and Reporting Forms

- NJ Transit Student Discount

- Bike Rental Agreement

- Climate Neutrality

- Keep It On The Screen

- Get Outdoors

- Recycling Guide

- Student Groups

- Meet the Team

- Partner with Us

- Share a Profile Recommendation

- Share Your News

- Action Scholar Questionnaire

- The Communications Toolkit

- Policies & Guides

- Internal Forms

- Meet Our Staff

- Banner Requests

- Treasury Services

- Accounts Payable

- Business Entertainment Policy

- Chart of Accounts

- Program Codes

- Credit Card Policies and Procedures

- “How To” Guides

- Vendor Code of Conduct

- Contractor Guidelines

- Purchase Order Terms & Conditions

- STORES Requisition Form

- Travel Policy and Procedures

- Requisition to Purchase Order

- Non-PO Purchases

- Standing (Blanket) Purchase Orders

- University Contracting

- Student Accounts

- University Events, Announcements, and Resources for Staff

- Executive Board

- Constitution and By-laws

- Volunteer Opportunities

- President’s Award for Distinguished Staff Service

- Instructional Technology Department

- Opportunities

- Campus Event Spaces and Documentation

- Voice Services

- Password Self-Service

- Passwords and Logging In

- Technology Services Portfolio

- Teaching Remotely

- Learning Remotely

- Working Remotely

- Your Internet Connection

- Two-Factor Authentication Self-Service

- Loaner Policy

- User Support Policies

- Departmental Computer Purchase Policy

- Google Shared Drives Policy

- Responsible Use of University Data

- Microsoft Campus Agreement

- Network User Agreement

- Laptop Program

- The Alan Candiotti Fund

- Work For Us

- MAT Program Information

- Student Right to Know

- Student Complaints Resolution

- Institutional Research

- About Policies

- University Complaint & Grievance Policies & Procedures

- Protect The Forest

- Programs of Study

- CLA Dean’s List

- Drew Scholarships, Fellowships, Grants and Award Winners

- Phi Beta Kappa, Gamma of NJ

- Community Education Audit Program

- Specialized Honors Guide

- Faculty Highlights

- Center for Language and Learning

- Center on Religion, Culture and Conflict

- Religion and Global Health Forum

- Faculty by Program

- Announcements

- City semesters

- Non-Degree Students

- Summer Intensive

- Team Projects

- Student Information Form

- Application Form

- Accepted Students

- Summer Term

- Class Schedule & Course Information

- Academic Calendars

- Frequently Asked Questions: Registration

- Ladder Degree Audit

- Petitions to Academic Standing

- Cross Registration

- Final Exam Schedule

- Registering for a Closed Class with an Override

- Add or Drop a Class Simultaneously

- Declaration or Change of Major and Minor – (CLA) Student Instructions

- Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA)

- Musical Instruction Registration

- Digital Diplomas & Certificates

- Credential Validation

- Individual Instruction (Independent Study) Registration Request for CLA

- Transcript Requests

- Notarization Requests

- Veteran Benefits at Drew University

- Approving a Declaration/Change of Major/Minor

- Grade Information

- Registration Overrides

- Request for Student Data Information

- Roster Verification

- Writing a Course Description

- Viewing Your Waitlist

- Course Attribute Overview

- Locating a Student’s PIN

- Transfer Credit

- Transcripts & Enrollment Verification

- Graduation & Diplomas

- Contact/Meet the Staff

- Meet The Mentors

- Meet the Faculty/Staff

- First-Year Toolkit

- Academic Alerts (Beacon) – for Students

- CAE LibGuide

- Remote Learning Resources

- Location and Staff

- Accommodate

- Getting Started

- Current Students

- Documentation Guidelines

- Policies and Procedures

- Rights and Responsibilities

- Faculty Resources

- Information for Parents

- University Writing Center

- Academic Alerts (Beacon) – for Faculty

- Academic Integrity for CLA Faculty

- Policies and Forms

- Further Resources

- Work at the CAE

- Library Services and Resources

- Research Resources

- Special Collections & University Archives

- Digital Collections

- News, Events, and Podcast

- Giving to the Library

- About the Library

- Internship Registration

- Internship Awards

- Full-time Job Searches

- Pre-Health Advising

- Make a Donation

- Student Resources

- Professionals in Residence

- For Faculty and Staff

- Presentations

- Internship Evaluations

- Our Approach

- First Destination Survey

- First Destinations

- AmeriCorps Safer Communities Initiative

- Arts of Respect High School Program

- Qisasna (Our Stories) US/Yemeni Podcast Program

- “We Refuse to Be Enemies”: Author talk with Sabeeha Rehman and Walter Ruby

- Reflections

- CRCC and Afghan Girls Financial Assistance Fund Partnership

- Global Learning

- Distinguished Visiting Scholars

- Drucker Fellows Program Arts of Respect

- Drew University Institute for Emerging Leaders

- Drew Institute on Religion and Conflict Transformation

- The Peacebuilder Award

- The Shirley Sugerman Interfaith Forum

- Past Events

- Make a Gift

- Civic Engagement Showcase & Awards

- Action Scholars

- Changemakers Certificate Program

- Drew Food Pantry

- MLK Day of Service

- Immersive Experiences

- Sustainability At Drew

- Democracy at Drew

- Civic Scholars

- Get Engaged

- Featured Stories

- Staff and Faculty

- Board of Associates

- Schedule of Events

- Summer Institute (DHSI)

- Projects & Courses

- Technology Fellows

- Tools & Resources

- Meet the Director

- Mentors and Projects

- Information for Students

- Information for Mentors

- Our Research Fellows

- RISE Student Information Form

- RISE Talk Series

- Drew Summer Science Institute (DSSI)

- Heroes in Drug Discovery

- Meet the Co-Chairs

- Facilities & Instrumentation

- Social Impact

- Museums and Cultural Management

- United Nations

- Communications & Media

- New York Theatre

- Contemporary Art

- Wall Street

- Art and Cultures of the Mediterranean in Southern France and Morocco

- Building a Sustainable Creative Practice in India

- Community Resilience and Prosperity in Vietnam

- Food, Culture, and Sustainability in Tuscany

- Healthcare and Human Development in South Africa

- Psychology of Group Conflict and Reconciliation in South Africa

- Spanish Language & Culture in Barcelona

- London Semester

- Global Partner Programs

- TREC Finances

- TREC Ambassadors

- Health and Safety Protocols

- View our Academic Programs

- Admissions Counselors by Area

- Meet Our Student Tour Guides

- Drew Accolades

- Tuition & Fees

- Transfer Students

- International Admissions

- International Baccalaureate Students

- Courses On Campus

- Continuing Ed and Non-Degree Programs

- Test Optional Policy

- For Parents

- You’re Invited!

- Campus Visit

- Graduate Tuition

- International Students

- Virtual Tour

- Undergraduate Visits & Events

- Graduate Visits & Events

- Student Orientation

- Verification and Outstanding Requirements

- Applicants to Drew’s EOF Program

- Drew Scholarship for the Arts

- BA/MD Dual Degree Program & Scholarship

- Meet The Faculty

- Action Scholars Take Action!

- Student Employment & Work Study

- Financial Aid Advisors

- Financing Your Education

- Cost of Attendance

- Cost Calculator

- Tuition and Fees Schedules

- Payment Options

- 1098-T Information

- Health Insurance

- Authorized Viewer Setup (PROXY)

- Credit Refund Information

- Federal Perkins Loan

- Institutional Refund Policies (Withdrawal / Leave of Absence from University)

- Refunds of Federal and State Aid

- Student Accounts Office Holds

- Student Loan Disbursement

- Understanding Your Bill

- Military / Veterans

- Alumni Community

- Stay Connected

- Planned Giving

- What to Support

- Ways to Give

- University Advancement

- Club Sports

- Intramural Activities & Classes

- File a Report

- Active Shooter Response Training Video

- Annual Fire Safety and Security Report/Clery Statistics

- Daily Crime & Fire Log

- LiveSafe at Drew

- Meet The Staff

- Parking and Motor Vehicle Information

- Sexual and Relationship Violence and Prevention

- Well-being@Drew

- Group Psychotherapy

- What to Expect in Counseling/Therapy

- Workshops/Seminars

- Self Help & Resources

- For Faculty/Staff

- Counseling Staff

- Emergency Information

- Hours and Services

- Information and Updates

- New Students: Submitting Your Health Forms

- Insurance Information

- Additional Health Resources

- International Travel Advisory

- Dining Hours

- Diversity Equity & Inclusion Programming

- Office of the Chaplain & Religious Life

- Hoyt-Bowne & Asbury Hall

- McLendon, McClintock, Foster & Hurst Hall

- Haselton, Eberhardt, Riker, & Baldwin Hall

- Holloway Hall

- Tolley, Brown & Welch Hall

- Undergraduate Theme Houses

- Specialized Floors

- Tipple Hall

- Housing Process

- Residence Hall Floor Plans

- Important Housing Dates

- Room Selection Process

- Grad/Theo New Resident Information

- Grad/Theo Current Resident Information

- Community Advisors & House Assistants

- Gender Inclusive Housing

- Faculty & Staff

- LGBTQ+ History, Activism & Education

- Mentorship Program

- Graphics & Flag Info

- Visa Application Information

- International Student Orientation

- Before Booking Your Flight

- I20 Information and Application

- DS-2019 Info And Application

- New Caspersen and Theology Students

- International Student FAQs Fall 2023

- On Campus Employment

- Undergraduate CPT Application Process

- Graduate Student CPT Application

- Optional Practical Training (OPT)

- Students on Approved OPT

- J-1 Academic Training

- Tax Information

- i-House Fall 2023 Application Form for New Students

- One To World

- Tilghman International Awards

- International Ambassador Program

- Asian Student Union

- International Students Association

- Extra Time On Exams For International Students

- Info for Faculty & Staff

- Family Visits

- INTO Drew University

- Student Activities

- Diversity Initiatives & Programs

- Financial Policies & Procedures

- Funding an Event

- Before the Event

- Posting Policy

- Campus Wide Announcement Policies and Procedures

- Off-Campus Trips

- Post-Event Responsibilities

- Fundraising Guidelines

- Club Events

- Responding to Current Events

- Off-Campus Event Registration form

- Ad-hoc Request Form

- Club Website Information

- Event Review Form

- Rights & Responsibilities

- Student Event Policies

- Graduate & Theological Student Groups & Associations

- Student Government Funded Club Fundraising Policies

- Purchases & Student Travel

- Supplies & Resources

- Alcohol at Student Events

- Offices & Storage Spaces

- Digital Signage in the Ehinger Center

- Club Email Access

- Club Leader Position Information

- Path Instructions for Club Leaders

- Well-being @ Drew

- Volunteer Without Borders

- The Ehinger Center

- Staff Contact

- Winter Orientation

- Summer Orientation

- Fall Orientation

- Transfer Orientation

- Commuter Students

- Orientation Committee

- Placement Exams

- Parents & Families

- Parking on Campus

- Drew Seminar Course Descriptions

- Family Weekend

- Title IX Staff

- Decorum Policy

- Local, State and National Resources

- Trans* Equality Policy Statement

- Campus Climate Survey Results

- Non-Discrimination of Students on the Basis of Pregnancy, Childbirth, and Related Conditions

- Commencement FAQ

- Campus Map/Parking

- Commemorative Program Request

- Apply to Graduate

- Diploma Requests

- Past Commencement Speakers and Honorary Degree Recipients

- Zipcars at Drew

- Caspersen School of Graduate Studies

- Drew Theological School

- Departments & Offices

- Maps & Directions

- Privacy Policy

Connect With Us

- Staff Spotlight

- TREC Planning

- View our Academic Program

- Drew Planned Giving

- What To Support

- Athletics & Recreation

- Social Security

- Drew Connect

- Black Alumni Association

- Young Alumni

- Alumni Services & Discounts

- Alumni Achievement Awards: Recipients

- Virtual Alumni Art Show

- Senior Gift Society

- Giving Societies

- Giving Home

- Gift Options

- About Bequests

- Calculators

- Write-to-Learn Assignments

by [email protected] | Nov 13, 2023

Writing Studies

- Drew Seminar Writing Resources

- Resources for Writing Intensive Courses

- Why Use Writing Workshops and How to Use Them Well

- Types of Workshops – Structures that Work

- Workshops That Work – Write-to-Learn

- Workshops That Work – Drafts & Revision

Connections Experiences Opportunities

- Academics >

- Writing Studies >

- Resources for Teaching Writing >

What is Write-Learn Pedagogy?

Write-to-Learn pedagogy builds on the fact that writing promotes active learning. Writing-to-Learn assignments invite students to explore ideas raised in class discussion or reading, rephrase course content in their own words, make tentative connections, hypothesize, inventory what they know at this point in the class, and try out interpretations. WTL assignments also invite students to develop questions and take risks in content and style.WTL assignments can be a few sentences or paragraphs long, as they are in College Seminars. In other contexts, such as writing intensive courses, they may be papers. What marks them as WTL assignments is their purpose and the way they are integrated into the content of the class and help accomplish the learning goals of the class.

When Should I Assign WTL in Class and How Do I Engage Students?

Below are some sample Writing-to-Learn assignments, most collected from Drew classes (with a few additions) and some notes about how to build them into a class. Try assigning one of these at the beginning of class, during class, at the end of class, or as part of a homework assignment. Remember that we learn best through repetition, so these will be most effective if you assign one kind of WTL strategy on several different occasions; however, it is important to incorporate them into the class so the work does not seem like “busy work” and so that the objectives of the assignments meet the learning goals of the course.

| you have about the topic or reading and then organize the questions in whatever way makes sense to you (e.g.: the content of the reading, the context, the author, connections between it and other texts, responses other students had to the reading or topic in class), finally, prioritize the questions and decide which must be addressed first and which answers might lead to other answers. | |

| of the main ideas of the reading for a student who missed class or couldn’t do the reading because of illness (write as you’d talk, and try not to be long-winded). | |

| connects with, challenges, or builds upon other readings for the class and note which you find the most interesting or surprising connection. | |

| of three or four to list three ways that the reading connects with, challenges, or builds upon other readings for the class. | |

| how X is different from (or similar to) Y. | |

| picture or representation (a graph or diagram or flow chart or ?) of this concept or notion or process and explain how the pictorial representation should be “read.” | |

| assigned for tonight’s homework might say based on its title and on your previous experience. | |

| of a process or procedure. Explain what goes into your educated guess and what could throw it off. | |

| might be answered by a simple google/wikipedia search? How would you test the accuracy of the answer you find? | |

| ) that you are sure about right now and explain what makes you sure of this one thing. | |

| that you still have about the topic/material discussed in class today and describe one strategy/process/procedure you could follow to try to answer this question. | |

| you still have about this topic/material and then organize the questions in whatever way makes sense to you (e.g.: the content of the reading, the context, the author, connections between it and other texts, responses students had to the reading or the topic in class), finally, prioritize the questions and decide which must be addressed first and which answers might lead to other answers. | |

| you would like to have someone address as part of your discussion of this reading / film / image / music / play / poem / etc. Post these questions to Moodle at least 24 hours before class. | |

| to one of the questions posted by someone else in the class. | |

| of the argument of the article you just read. Draw a picture or diagram, make a chart or a list – choose whatever visual representation most clearly lays out the structure of the argument for you. | |

| of the article you read for class. Identify the main point of the argument and several key subordinate points. | |

| with some aspect of the argument advanced by the writer of this reading (state the argument and then explain why you agree). | |

| to other readings or material discussed in class (first state the argument and then expand on it). | |

| with some aspect of the argument advanced by the writer of this reading (state the argument and then explain how [and why] you disagree). | |

| between this argument and the other one you have identified. Do they agree or disagree? Are they making similar arguments but in different ways? | |

| between two or more of the authors you have read this semester. Each “character” should speak in the voice of the text you read and express the opinions expressed in the text; however, you can decide what aspect of the topic they discuss. | |

| , example, case study, or quotation from the reading and explain how the author uses it to support the larger argument of the piece. Do you believe that use was successful? (explain your answer). | |

| , case study, image, or quotation from the reading that could be used to support a different argument, and explain how that would work. | |

| and write a question you might pose to the author / the artist who created this work / the photographer / the film-maker / the playwright / the poet, etc. | |

| of any other books and/or articles written by the author of the material you just read. Include the title of the book or article, who published it, and where and when it was published. What does this list reveal about the author? Does it change your response to what you read? If so, how? If not, why not? | |

| in the reading and make a bibliography of other books and/or articles he or she has written. Include the title of the book or article, who published it, where it was published, and when it was published. What does this list tell you about the author? Does it change your sense of whether he or she was a good source for the article to quote (you can define “good” in this context). | |

| ) for the topic we have been discussing. The first for a standard college-level encyclopedia to which students might turn for an accurate definition/ explanation; the second for an on-line reference that the general public might consult for a quick and simple definition/explanation; the third for a “hip” encyclopedia to be marketed to middle-school students and available for iPhones and other portable devices. | This assignment connects with work in the College Writing class by asking students to practice summary-writing and to think about the ways audience and purpose shape our writing decisions. |

| of the image or sequence of images/event/experiment/piece of music we have been discussing. Write the description for an academic audience. Then write a second description that would make sense to a child. Finally, write about the difference between your two descriptions and the decision-process you used as you imagined each audience and adjusted your description accordingly. | |

| (story) of the ways your thinking about this topic or perspective has evolved (or nor). What did you first think when you were exposed to it? Then what did you think? Then what? Try to get everything down in sequence and include your confusions as well as your understandings. | |

Jump to navigation

- Inside Writing

- Teacher's Guides

- Student Models

- Writing Topics

- Minilessons

- Shopping Cart

- Inside Grammar

- Grammar Adventures

- CCSS Correlations

- Infographics

Get a free Grammar Adventure! Choose a single Adventure and add coupon code ADVENTURE during checkout. (All-Adventure licenses aren’t included.)

Sign up or login to use the bookmarking feature.

10 Activities for Writing to Learn

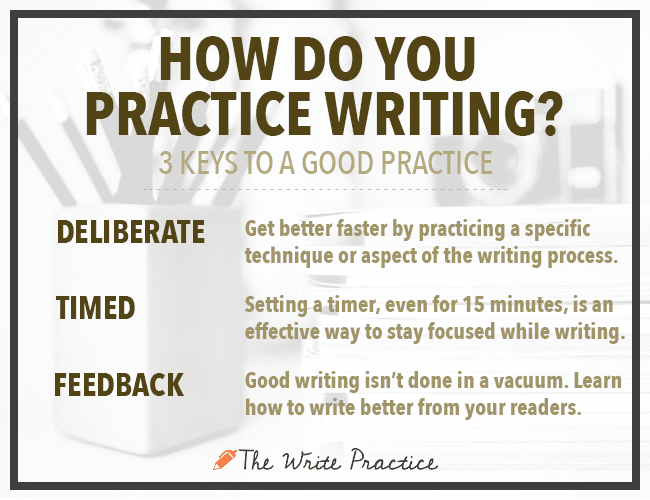

In Language Arts, students learn to write —narratives, explanatory essays, arguments, reports, and literary analyses. In other classes, they write to learn —notes, summaries, lab reports, emails, and reflections. Writing helps students gain knowledge, wrestle with it, and reflect on it.

You can use 10 simple writing-to-learn activities to supercharge learning in any class throughout the day.

1. Entrance and Exit Slips

When students file into your class, greet them with a quick writing prompt:

- What's the most surprising thing you learned yesterday?

- If you could be anywhere right now, where would you go?

- What would you ask Abraham Lincoln?

- What's your favorite planet, and why?

Tailor the prompt to your situation. You might provide a warm-up for today's lesson, or a reflection on something you are studying, or just a check-in on how students are feeling. They can write their answers on little strips of paper you have in a basket by the door, allowing you to gather them and read a select few. Or students can write their answers in their notebooks and volunteer to read their own ideas aloud.

Repeat the activity at the end of class, writing a new prompt. Let some students share their exit-slip answers before you dismiss them, or gather answers to read at the beginning of the next class.

Entrance and exit slips help students tune in to the learning environment of your class and take what they learn with them.

2. Stop 'n' Write

At any point in a lesson, you can have students stop and write to reflect on what they are learning. Once again, you provide them a prompt, either written on the board or spoken aloud:

- Who do you know who is most like the Great Gilly Hopkins? Why?

- What's the most important job of the president of the United States?

- What's the coolest thing about trees?

- In the Revolutionary War, what side would you be on?

After students write their responses, have volunteers share their observations. Writing deepens learning within a student, and sharing broadens learning across the classroom. Stop 'n' Write also shifts gears, engaging students who have begun to drift. Try this stop-'n'-write minilesson .

3. Nutshelling

Students enjoy the challenge of creating quick summaries. Discussing these summaries helps everyone review key concepts. Try this nutshelling minilesson .

4. Graph It!

- Cluster: In the middle of a page, students write a topic and circle it. They write related ideas around it and connect these ideas in a cluster or mind map. (For example, "Create a cluster about the Boston Tea Party.")

- Time line: Have students organize events in chronological order using a time line. Try this time-line minilesson .

- Pro-Con Chart: Students make a T-chart and write the "pros" of a topic in the left-hand column and the "cons" in the right-hand column. (For example, what are the pros and cons of solar power?) Try this pro-con chart minilesson .

- Cause-Effect Chart: Students make a T-chart and write the causes of a phenomenon in the left-hand column and the effects in the right-hand column. Or students can try this advanced cause-effect chart . (For example, what are the causes and effects of the Civil Rights Movement.)

- Venn Diagram: Students draw two overlapping circles and label each side with a topic. They write similarities in the shared space and differences in the outside spaces. (For example, what are the similarities and differences between hobbits and dwarves?)

5. Sense It!

Ask students to write sensations connected to a topic: sights, sounds, smells, textures, tastes, and touch sensations. The subject can be anything students have experienced or read about, or anything they could imagine. Thanksgiving Senses

- Sounds: Laughter in the kitchen, football on TV, boiling potatoes

- Smells: Roasted turkey, fresh-baked bread, green-bean casserole

- Tastes: Melted butter, savory gravy, sage dressing

- Touch sensations: Hot rolls, soft napkins, straining bellies

Sense details can enliven any writing. Try this minilesson to help students write paragraphs that show instead of tell.

6. Journalistic Questions

When writing a news story, journalists seek to answer the 5 W's and H about their topic: Who? What? When? Where? Why? and How?

Second Continental Congress

- What? Signed the Declaration of Independence

- When? July 4, 1776

- Where? The Pennsylvania State House (Independence Hall)

- Why? To declare their freedom from England

- How? Those present signed, and the document was taken for others to sign.

Use this 5 W's and H minilesson . Ask your students to answer the same questions about any topic you are studying, helping them to get the "whole story."

7. Ask "What If?"

Instead of asking students what did happen, ask them what didn't. Counterfactual reasoning lets students explore possibilities and thereby better understand what actually did take place:

- What if Rosa Parks had given up her seat?

- What if we had a king instead of a president?

- What if money really did grow on trees?

- What if human beings set up a colony on Mars?

These sorts of questions invite students to use their imaginations to understand a topic in a whole new way. Also, some of the greatest inventions in history have come from answering "what if" questions. (For example, "What if books could be printed by a machine instead of being copied by hand?")

Try this "what if" minilesson.

8. Life Maps

9. Freewrite

Have students write without stopping for five minutes about any topic. Tell them to just keep going. If they can't think of what to write, they should write about that fact until they come up with a new idea:

Try this freewriting minilesson with your students.

10. Dialogues

Writing is communication, so why not have your students write dialogues back and forth with each other? Here are a few options:

- Back-and-forth stories: Have one student write a paragraph to start a story and then hand the work to another student. That person writes the next paragraph and passes the story back, and so on. Use this back-and-forth stories minilesson .

- Historical dialogue: Have students write a conversation between them and a historical figure. Students use their imaginations and what they know about the person to bring history to life. Try this historical-dialogue minilesson .

Writing to Learn

Writing helps students process what they are learning, creating deeper connections with what they already know.

For more help teaching writing, check out these handbook programs from Thoughtful Learning:

- Kindergarten: The Writing Spot

- Grade 1: Write One

- Grade 2: Write Away

- Grade 3: Write on Track

- Grades 4-5: Writers Express

- Grades 6-8: Write on Course 20-20

- Grades 9-10: Write Ahead

- Grades 11-12: Write for College

Teacher Support:

Click to find out more about this resource.

Standards Correlations:

The State Standards provide a way to evaluate your students' performance.

Writing to Learn: Activities that Foster Engagement and Understanding

Posted on January 22, 2019 by John Paul Kanwit