Feb 15, 2023

6 Example Essays on Social Media | Advantages, Effects, and Outlines

Got an essay assignment about the effects of social media we got you covered check out our examples and outlines below.

Social media has become one of our society's most prominent ways of communication and information sharing in a very short time. It has changed how we communicate and has given us a platform to express our views and opinions and connect with others. It keeps us informed about the world around us. Social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and LinkedIn have brought individuals from all over the world together, breaking down geographical borders and fostering a genuinely global community.

However, social media comes with its difficulties. With the rise of misinformation, cyberbullying, and privacy problems, it's critical to utilize these platforms properly and be aware of the risks. Students in the academic world are frequently assigned essays about the impact of social media on numerous elements of our lives, such as relationships, politics, and culture. These essays necessitate a thorough comprehension of the subject matter, critical thinking, and the ability to synthesize and convey information clearly and succinctly.

But where do you begin? It can be challenging to know where to start with so much information available. Jenni.ai comes in handy here. Jenni.ai is an AI application built exclusively for students to help them write essays more quickly and easily. Jenni.ai provides students with inspiration and assistance on how to approach their essays with its enormous database of sample essays on a variety of themes, including social media. Jenni.ai is the solution you've been looking for if you're experiencing writer's block or need assistance getting started.

So, whether you're a student looking to better your essay writing skills or want to remain up to date on the latest social media advancements, Jenni.ai is here to help. Jenni.ai is the ideal tool for helping you write your finest essay ever, thanks to its simple design, an extensive database of example essays, and cutting-edge AI technology. So, why delay? Sign up for a free trial of Jenni.ai today and begin exploring the worlds of social networking and essay writing!

Want to learn how to write an argumentative essay? Check out these inspiring examples!

We will provide various examples of social media essays so you may get a feel for the genre.

6 Examples of Social Media Essays

Here are 6 examples of Social Media Essays:

The Impact of Social Media on Relationships and Communication

Introduction:.

The way we share information and build relationships has evolved as a direct result of the prevalence of social media in our daily lives. The influence of social media on interpersonal connections and conversation is a hot topic. Although social media has many positive effects, such as bringing people together regardless of physical proximity and making communication quicker and more accessible, it also has a dark side that can affect interpersonal connections and dialogue.

Positive Effects:

Connecting People Across Distances

One of social media's most significant benefits is its ability to connect individuals across long distances. People can use social media platforms to interact and stay in touch with friends and family far away. People can now maintain intimate relationships with those they care about, even when physically separated.

Improved Communication Speed and Efficiency

Additionally, the proliferation of social media sites has accelerated and simplified communication. Thanks to instant messaging, users can have short, timely conversations rather than lengthy ones via email. Furthermore, social media facilitates group communication, such as with classmates or employees, by providing a unified forum for such activities.

Negative Effects:

Decreased Face-to-Face Communication

The decline in in-person interaction is one of social media's most pernicious consequences on interpersonal connections and dialogue. People's reliance on digital communication over in-person contact has increased along with the popularity of social media. Face-to-face interaction has suffered as a result, which has adverse effects on interpersonal relationships and the development of social skills.

Decreased Emotional Intimacy

Another adverse effect of social media on relationships and communication is decreased emotional intimacy. Digital communication lacks the nonverbal cues and facial expressions critical in building emotional connections with others. This can make it more difficult for people to develop close and meaningful relationships, leading to increased loneliness and isolation.

Increased Conflict and Miscommunication

Finally, social media can also lead to increased conflict and miscommunication. The anonymity and distance provided by digital communication can lead to misunderstandings and hurtful comments that might not have been made face-to-face. Additionally, social media can provide a platform for cyberbullying , which can have severe consequences for the victim's mental health and well-being.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, the impact of social media on relationships and communication is a complex issue with both positive and negative effects. While social media platforms offer many benefits, such as connecting people across distances and enabling faster and more accessible communication, they also have a dark side that can negatively affect relationships and communication. It is up to individuals to use social media responsibly and to prioritize in-person communication in their relationships and interactions with others.

The Role of Social Media in the Spread of Misinformation and Fake News

Social media has revolutionized the way information is shared and disseminated. However, the ease and speed at which data can be spread on social media also make it a powerful tool for spreading misinformation and fake news. Misinformation and fake news can seriously affect public opinion, influence political decisions, and even cause harm to individuals and communities.

The Pervasiveness of Misinformation and Fake News on Social Media

Misinformation and fake news are prevalent on social media platforms, where they can spread quickly and reach a large audience. This is partly due to the way social media algorithms work, which prioritizes content likely to generate engagement, such as sensational or controversial stories. As a result, false information can spread rapidly and be widely shared before it is fact-checked or debunked.

The Influence of Social Media on Public Opinion

Social media can significantly impact public opinion, as people are likelier to believe the information they see shared by their friends and followers. This can lead to a self-reinforcing cycle, where misinformation and fake news are spread and reinforced, even in the face of evidence to the contrary.

The Challenge of Correcting Misinformation and Fake News

Correcting misinformation and fake news on social media can be a challenging task. This is partly due to the speed at which false information can spread and the difficulty of reaching the same audience exposed to the wrong information in the first place. Additionally, some individuals may be resistant to accepting correction, primarily if the incorrect information supports their beliefs or biases.

In conclusion, the function of social media in disseminating misinformation and fake news is complex and urgent. While social media has revolutionized the sharing of information, it has also made it simpler for false information to propagate and be widely believed. Individuals must be accountable for the information they share and consume, and social media firms must take measures to prevent the spread of disinformation and fake news on their platforms.

The Effects of Social Media on Mental Health and Well-Being

Social media has become an integral part of modern life, with billions of people around the world using platforms like Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter to stay connected with others and access information. However, while social media has many benefits, it can also negatively affect mental health and well-being.

Comparison and Low Self-Esteem

One of the key ways that social media can affect mental health is by promoting feelings of comparison and low self-esteem. People often present a curated version of their lives on social media, highlighting their successes and hiding their struggles. This can lead others to compare themselves unfavorably, leading to feelings of inadequacy and low self-esteem.

Cyberbullying and Online Harassment

Another way that social media can negatively impact mental health is through cyberbullying and online harassment. Social media provides a platform for anonymous individuals to harass and abuse others, leading to feelings of anxiety, fear, and depression.

Social Isolation

Despite its name, social media can also contribute to feelings of isolation. At the same time, people may have many online friends but need more meaningful in-person connections and support. This can lead to feelings of loneliness and depression.

Addiction and Overuse

Finally, social media can be addictive, leading to overuse and negatively impacting mental health and well-being. People may spend hours each day scrolling through their feeds, neglecting other important areas of their lives, such as work, family, and self-care.

In sum, social media has positive and negative consequences on one's psychological and emotional well-being. Realizing this, and taking measures like reducing one's social media use, reaching out to loved ones for help, and prioritizing one's well-being, are crucial. In addition, it's vital that social media giants take ownership of their platforms and actively encourage excellent mental health and well-being.

The Use of Social Media in Political Activism and Social Movements

Social media has recently become increasingly crucial in political action and social movements. Platforms such as Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram have given people new ways to express themselves, organize protests, and raise awareness about social and political issues.

Raising Awareness and Mobilizing Action

One of the most important uses of social media in political activity and social movements has been to raise awareness about important issues and mobilize action. Hashtags such as #MeToo and #BlackLivesMatter, for example, have brought attention to sexual harassment and racial injustice, respectively. Similarly, social media has been used to organize protests and other political actions, allowing people to band together and express themselves on a bigger scale.

Connecting with like-minded individuals

A second method in that social media has been utilized in political activity and social movements is to unite like-minded individuals. Through social media, individuals can join online groups, share knowledge and resources, and work with others to accomplish shared objectives. This has been especially significant for geographically scattered individuals or those without access to traditional means of political organizing.

Challenges and Limitations

As a vehicle for political action and social movements, social media has faced many obstacles and restrictions despite its many advantages. For instance, the propagation of misinformation and fake news on social media can impede attempts to disseminate accurate and reliable information. In addition, social media corporations have been condemned for censorship and insufficient protection of user rights.

In conclusion, social media has emerged as a potent instrument for political activism and social movements, giving voice to previously unheard communities and galvanizing support for change. Social media presents many opportunities for communication and collaboration. Still, users and institutions must be conscious of the risks and limitations of these tools to promote their responsible and productive usage.

The Potential Privacy Concerns Raised by Social Media Use and Data Collection Practices

With billions of users each day on sites like Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, social media has ingrained itself into every aspect of our lives. While these platforms offer a straightforward method to communicate with others and exchange information, they also raise significant concerns over data collecting and privacy. This article will examine the possible privacy issues posed by social media use and data-gathering techniques.

Data Collection and Sharing

The gathering and sharing of personal data are significant privacy issues brought up by social media use. Social networking sites gather user data, including details about their relationships, hobbies, and routines. This information is made available to third-party businesses for various uses, such as marketing and advertising. This can lead to serious concerns about who has access to and uses our personal information.

Lack of Control Over Personal Information

The absence of user control over personal information is a significant privacy issue brought up by social media usage. Social media makes it challenging to limit who has access to and how data is utilized once it has been posted. Sensitive information may end up being extensively disseminated and may be used maliciously as a result.

Personalized Marketing

Social media companies utilize the information they gather about users to target them with adverts relevant to their interests and usage patterns. Although this could be useful, it might also cause consumers to worry about their privacy since they might feel that their personal information is being used without their permission. Furthermore, there are issues with the integrity of the data being used to target users and the possibility of prejudice based on individual traits.

Government Surveillance

Using social media might spark worries about government surveillance. There are significant concerns regarding privacy and free expression when governments in some nations utilize social media platforms to follow and monitor residents.

In conclusion, social media use raises significant concerns regarding data collecting and privacy. While these platforms make it easy to interact with people and exchange information, they also gather a lot of personal information, which raises questions about who may access it and how it will be used. Users should be aware of these privacy issues and take precautions to safeguard their personal information, such as exercising caution when choosing what details to disclose on social media and keeping their information sharing with other firms to a minimum.

The Ethical and Privacy Concerns Surrounding Social Media Use And Data Collection

Our use of social media to communicate with loved ones, acquire information, and even conduct business has become a crucial part of our everyday lives. The extensive use of social media does, however, raise some ethical and privacy issues that must be resolved. The influence of social media use and data collecting on user rights, the accountability of social media businesses, and the need for improved regulation are all topics that will be covered in this article.

Effect on Individual Privacy:

Social networking sites gather tons of personal data from their users, including delicate information like search history, location data, and even health data. Each user's detailed profile may be created with this data and sold to advertising or used for other reasons. Concerns regarding the privacy of personal information might arise because social media businesses can use this data to target users with customized adverts.

Additionally, individuals might need to know how much their personal information is being gathered and exploited. Data breaches or the unauthorized sharing of personal information with other parties may result in instances where sensitive information is exposed. Users should be aware of the privacy rules of social media firms and take precautions to secure their data.

Responsibility of Social Media Companies:

Social media firms should ensure that they responsibly and ethically gather and use user information. This entails establishing strong security measures to safeguard sensitive information and ensuring users are informed of what information is being collected and how it is used.

Many social media businesses, nevertheless, have come under fire for not upholding these obligations. For instance, the Cambridge Analytica incident highlighted how Facebook users' personal information was exploited for political objectives without their knowledge. This demonstrates the necessity of social media corporations being held responsible for their deeds and ensuring that they are safeguarding the security and privacy of their users.

Better Regulation Is Needed

There is a need for tighter regulation in this field, given the effect, social media has on individual privacy as well as the obligations of social media firms. The creation of laws and regulations that ensure social media companies are gathering and using user information ethically and responsibly, as well as making sure users are aware of their rights and have the ability to control the information that is being collected about them, are all part of this.

Additionally, legislation should ensure that social media businesses are held responsible for their behavior, for example, by levying fines for data breaches or the unauthorized use of personal data. This will provide social media businesses with a significant incentive to prioritize their users' privacy and security and ensure they are upholding their obligations.

In conclusion, social media has fundamentally changed how we engage and communicate with one another, but this increased convenience also raises several ethical and privacy issues. Essential concerns that need to be addressed include the effect of social media on individual privacy, the accountability of social media businesses, and the requirement for greater regulation to safeguard user rights. We can make everyone's online experience safer and more secure by looking more closely at these issues.

In conclusion, social media is a complex and multifaceted topic that has recently captured the world's attention. With its ever-growing influence on our lives, it's no surprise that it has become a popular subject for students to explore in their writing. Whether you are writing an argumentative essay on the impact of social media on privacy, a persuasive essay on the role of social media in politics, or a descriptive essay on the changes social media has brought to the way we communicate, there are countless angles to approach this subject.

However, writing a comprehensive and well-researched essay on social media can be daunting. It requires a thorough understanding of the topic and the ability to articulate your ideas clearly and concisely. This is where Jenni.ai comes in. Our AI-powered tool is designed to help students like you save time and energy and focus on what truly matters - your education. With Jenni.ai , you'll have access to a wealth of examples and receive personalized writing suggestions and feedback.

Whether you're a student who's just starting your writing journey or looking to perfect your craft, Jenni.ai has everything you need to succeed. Our tool provides you with the necessary resources to write with confidence and clarity, no matter your experience level. You'll be able to experiment with different styles, explore new ideas , and refine your writing skills.

So why waste your time and energy struggling to write an essay on your own when you can have Jenni.ai by your side? Sign up for our free trial today and experience the difference for yourself! With Jenni.ai, you'll have the resources you need to write confidently, clearly, and creatively. Get started today and see just how easy and efficient writing can be!

Start Writing With Jenni Today

Sign up for a free Jenni AI account today. Unlock your research potential and experience the difference for yourself. Your journey to academic excellence starts here.

Open Access is an initiative that aims to make scientific research freely available to all. To date our community has made over 100 million downloads. It’s based on principles of collaboration, unobstructed discovery, and, most importantly, scientific progression. As PhD students, we found it difficult to access the research we needed, so we decided to create a new Open Access publisher that levels the playing field for scientists across the world. How? By making research easy to access, and puts the academic needs of the researchers before the business interests of publishers.

We are a community of more than 103,000 authors and editors from 3,291 institutions spanning 160 countries, including Nobel Prize winners and some of the world’s most-cited researchers. Publishing on IntechOpen allows authors to earn citations and find new collaborators, meaning more people see your work not only from your own field of study, but from other related fields too.

Brief introduction to this section that descibes Open Access especially from an IntechOpen perspective

Want to get in touch? Contact our London head office or media team here

Our team is growing all the time, so we’re always on the lookout for smart people who want to help us reshape the world of scientific publishing.

Home > Books > Security and Privacy From a Legal, Ethical, and Technical Perspective

Social Media, Ethics and the Privacy Paradox

Submitted: 11 September 2019 Reviewed: 19 December 2019 Published: 05 February 2020

DOI: 10.5772/intechopen.90906

Cite this chapter

There are two ways to cite this chapter:

From the Edited Volume

Security and Privacy From a Legal, Ethical, and Technical Perspective

Edited by Christos Kalloniatis and Carlos Travieso-Gonzalez

To purchase hard copies of this book, please contact the representative in India: CBS Publishers & Distributors Pvt. Ltd. www.cbspd.com | [email protected]

Chapter metrics overview

3,994 Chapter Downloads

Impact of this chapter

Total Chapter Downloads on intechopen.com

Total Chapter Views on intechopen.com

Overall attention for this chapters

Today’s information/digital age offers widespread use of social media. The use of social media is ubiquitous and cuts across all age groups, social classes and cultures. However, the increased use of these media is accompanied by privacy issues and ethical concerns. These privacy issues can have far-reaching professional, personal and security implications. Ultimate privacy in the social media domain is very difficult because these media are designed for sharing information. Participating in social media requires persons to ignore some personal, privacy constraints resulting in some vulnerability. The weak individual privacy safeguards in this space have resulted in unethical and undesirable behaviors resulting in privacy and security breaches, especially for the most vulnerable group of users. An exploratory study was conducted to examine social media usage and the implications for personal privacy. We investigated how some of the requirements for participating in social media and how unethical use of social media can impact users’ privacy. Results indicate that if users of these networks pay attention to privacy settings and the type of information shared and adhere to universal, fundamental, moral values such as mutual respect and kindness, many privacy and unethical issues can be avoided.

- social media

Author Information

Nadine barrett-maitland *.

- University of Technology, Jamaica, West Indies

Jenice Lynch

*Address all correspondence to: [email protected]

1. Introduction

The use of social media is growing at a rapid pace and the twenty-first century could be described as the “boom” period for social networking. According to reports provided by Smart Insights, as at February 2019 there were over 3.484 billion social media users. The Smart Insight report indicates that the number of social media users is growing by 9% annually and this trend is estimated to continue. Presently the number of social media users represents 45% of the global population [ 1 ]. The heaviest users of social media are “digital natives”; the group of persons who were born or who have grown up in the digital era and are intimate with the various technologies and systems, and the “Millennial Generation”; those who became adults at the turn of the twenty-first century. These groups of users utilize social media platforms for just about anything ranging from marketing, news acquisition, teaching, health care, civic engagement, and politicking to social engagement.

The unethical use of social media has resulted in the breach of individual privacy and impacts both physical and information security. Reports in 2019 [ 1 ], reveal that persons between the ages 8 and 11 years spend an average 13.5 hours weekly online and 18% of this age group are actively engaged on social media. Those between ages 12 and 15 spend on average 20.5 hours online and 69% of this group are active social media users. While children and teenagers represent the largest Internet user groups, for the most part they do not know how to protect their personal information on the Web and are the most vulnerable to cyber-crimes related to breaches of information privacy [ 2 , 3 ].

In today’s IT-configured society data is one of, if not the most, valuable asset for most businesses/organizations. Organizations and governments collect information via several means including invisible data gathering, marketing platforms and search engines such as Google [ 4 ]. Information can be attained from several sources, which can be fused using technology to develop complete profiles of individuals. The information on social media is very accessible and can be of great value to individuals and organizations for reasons such as marketing, etc.; hence, data is retained by most companies for future use.

Privacy or the right to enjoy freedom from unauthorized intrusion is the negative right of all human beings. Privacy is defined as the right to be left alone, to be free from secret surveillance, or unwanted disclosure of personal data or information by government, corporation, or individual ( dictionary.com ). In this chapter we will define privacy loosely, as the right to control access to personal information. Supporters of privacy posit that it is a necessity for human dignity and individuality and a key element in the quest for happiness. According to Baase [ 5 ] in the book titled “A Gift of Fire: Social, Legal and Ethical Issues for Computing and the Internet,” privacy is the ability to control information about one’ s self as well as the freedom from surveillance from being followed, tracked, watched, and being eavesdropped on. In this regard, ignoring privacy rights often leads to encroachment on natural rights.

Intrusion—this can be viewed as encroachment (physical or otherwise) on ones liberties/solitude in a highly offensive way.

Privacy facts—making public, private information about someone that is of no “legitimate concern” to anyone.

False light—making public false and “highly offensive” information about others.

Appropriation—stealing someone’s identity (name, likeness) to gain advantage without the permission of the individual.

Technology, the digital age, the Internet and social media have redefined privacy however as surveillance is no longer limited to a certain pre-defined space and location. An understanding of the problems and dangers of privacy in the digital space is therefore the first step to privacy control. While there can be clear distinctions between informational privacy and physical privacy, as pointed out earlier, intrusion can be both physical and otherwise.

This chapter will focus on informational privacy which is the ability to control access to personal information. We examine privacy issues in the social media context focusing primarily on personal information and the ability to control external influences. We suggest that breach of informational privacy can impact: solitude (the right to be left alone), intimacy (the right not to be monitored), and anonymity (the right to have no public personal identity and by extension physical privacy impacted). The right to control access to facts or personal information in our view is a natural, inalienable right and everyone should have control over who see their personal information and how it is disseminated.

“Freely given—an individual must be given a genuine choice when providing consent and it should generally be unbundled from other terms and conditions (e.g., access to a service should not be conditional upon consent being given).”

“Specific and informed—this means that data subjects should be provided with information as to the identity of the controller(s), the specific purposes, types of processing, as well as being informed of their right to withdraw consent at any time.”

“Explicit and unambiguous—the data subject must clearly express their consent (e.g., by actively ticking a box which confirms they are giving consent—pre-ticked boxes are insufficient).”

“Under 13s—children under the age of 13 cannot provide consent and it is therefore necessary to obtain consent from their parents.”

Arguments can be made that privacy is a cultural, universal necessity for harmonious relationships among human beings and creates the boundaries for engagement and disengagement. Privacy can also be viewed as instrumental good because it is a requirement for the development of certain kinds of human relationships, intimacy and trust [ 7 ]. However, achieving privacy is much more difficult in light of constant surveillance and the inability to determine the levels of interaction with various publics [ 7 ]. Some critics argue that privacy provides protection against anti-social behaviors such as trickery, disinformation and fraud, and is thought to be a universal right [ 5 ]. However, privacy can also be viewed as relative as privacy rules may differ based on several factors such as “climate, religion, technological advancement and political arrangements” [ 8 , 9 ]. The need for privacy is an objective reality though it can be viewed as “culturally rational” where the need for personal privacy is viewed as relative based on culture. One example is the push by the government, businesses and Singaporeans to make Singapore a smart nation. According to GovTech 2018 reports there is a push by the government in Singapore to harness the data “new gold” to develop systems that can make life easier for its people. The [ 10 ] report points out that Singapore is using sensors robots Smart Water Assessment Network (SWAN) to monitor water quality in its reservoirs, seeking to build smart health system and to build a smart transportation system to name a few. In this example privacy can be describe as “culturally rational” and the rules in general could differ based on technological advancement and political arrangements.

In today’s networked society it is naïve and ill-conceived to think that privacy is over-rated and there is no need to be concerned about privacy if you have done nothing wrong [ 5 ]. The effects of information flow can be complex and may not be simply about protection for people who have something to hide. Inaccurate information flow can have adverse long-term implications for individuals and companies. Consider a scenario where someone’s computer or tablet is stolen. The perpetrator uses identification information stored on the device to access their social media page which could lead to access to their contacts, friends and friends of their “friends” then participate in illegal activities and engage in anti-social activities such as hacking, spreading viruses, fraud and identity theft. The victim is now in danger of being accused of criminal intentions, or worse. These kinds of situations are possible because of technology and networked systems. Users of social media need to be aware of the risks that are associated with participation.

3. Social media

The concept of social networking pre-dates the Internet and mass communication as people are said to be social creatures who when working in groups can achieve results in a value greater than the sun of its parts [ 11 ]. The explosive growth in the use of social media over the past decade has made it one of the most popular Internet services in the world, providing new avenues to “see and be seen” [ 12 , 13 ]. The use of social media has changed the communication landscape resulting in changes in ethical norms and behavior. The unprecedented level of growth in usage has resulted in the reduction in the use of other media and changes in areas including civic and political engagement, privacy and safety [ 14 ]. Alexa, a company that keeps track of traffic on the Web, indicates that as of August, 2019 YouTube, Facebook and Twitter are among the top four (4) most visited sites with only Google, being the most popular search engine, surpassing these social media sites.

Social media sites can be described as online services that allow users to create profiles which are “public, semi-public” or both. Users may create individual profiles and/or become a part of a group of people with whom they may be acquainted offline [ 15 ]. They also provide avenues to create virtual friendships. Through these virtual friendships, people may access details about their contacts ranging from personal background information and interests to location. Social networking sites provide various tools to facilitate communication. These include chat rooms, blogs, private messages, public comments, ways of uploading content external to the site and sharing videos and photographs. Social media is therefore drastically changing the way people communicate and form relationships.

Today social media has proven to be one of the most, if not the most effective medium for the dissemination of information to various audiences. The power of this medium is phenomenal and ranges from its ability to overturn governments (e.g., Moldova), to mobilize protests, assist with getting support for humanitarian aid, organize political campaigns, organize groups to delay the passing of legislation (as in the case with the copyright bill in Canada) to making social media billionaires and millionaires [ 16 , 17 ]. The enabling nature and the structure of the media that social networking offers provide a wide range of opportunities that were nonexistent before technology. Facebook and YouTube marketers and trainers provide two examples. Today people can interact with and learn from people millions of miles away. The global reach of this medium has removed all former pre-defined boundaries including geographical, social and any other that existed previously. Technological advancements such as Web 2.0 and Web 4.0 which provide the framework for collaboration, have given new meaning to life from various perspectives: political, institutional and social.

4. Privacy and social media

Social medial and the information/digital era have “redefined” privacy. In today’s Information Technology—configured societies, where there is continuous monitoring, privacy has taken on a new meaning. Technologies such as closed-circuit cameras (CCTV) are prevalent in public spaces or in some private spaces including our work and home [ 7 , 18 ]. Personal computers and devices such as our smart phones enabled with Global Positioning System (GPS), Geo locations and Geo maps connected to these devices make privacy as we know it, a thing of the past. Recent reports indicate that some of the largest companies such as Amazon, Microsoft and Facebook as well as various government agencies are collecting information without consent and storing it in databases for future use. It is almost impossible to say privacy exists in this digital world (@nowthisnews).

The open nature of the social networking sites and the avenues they provide for sharing information in a “public or semi-public” space create privacy concerns by their very construct. Information that is inappropriate for some audiences are many times inadvertently made visible to groups other than those intended and can sometimes result in future negative outcomes. One such example is a well-known case recorded in an article entitled “The Web Means the End of Forgetting” that involved a young woman who was denied her college license because of backlash from photographs posted on social media in her private engagement.

Technology has reduced the gap between professional and personal spaces and often results in information exposure to the wrong audience [ 19 ]. The reduction in the separation of professional and personal spaces can affect image management especially in a professional setting resulting in the erosion of traditional professional image and impression management. Determining the secondary use of personal information and those who have access to this information should be the prerogative of the individual or group to whom the information belongs. However, engaging in social media activities has removed this control.

Privacy on social networking sites (SNSs) is heavily dependent on the users of these networks because sharing information is the primary way of participating in social communities. Privacy in SNSs is “multifaceted.” Users of these platforms are responsible for protecting their information from third-party data collection and managing their personal profiles. However, participants are usually more willing to give personal and more private information in SNSs than anywhere else on the Internet. This can be attributed to the feeling of community, comfort and family that these media provide for the most part. Privacy controls are not the priority of social networking site designers and only a small number of the young adolescent users change the default privacy settings of their accounts [ 20 , 21 ]. This opens the door for breaches especially among the most vulnerable user groups, namely young children, teenagers and the elderly. The nature of social networking sites such as Facebook and Twitter and other social media platforms cause users to re-evaluate and often change their personal privacy standards in order to participate in these social networked communities [ 13 ].

While there are tremendous benefits that can be derived from the effective use of social media there are some unavoidable risks that are involved in its use. Much attention should therefore be given to what is shared in these forums. Social platforms such as Facebook, Twitter and YouTube are said to be the most effective media to communicate to Generation Y’s (Gen Y’s), as teens and young adults are the largest user groups on these platforms [ 22 ]. However, according to Bolton et al. [ 22 ] Gen Y’s use of social media, if left unabated and unmonitored will have long-term implications for privacy and engagement in civic activities as this continuous use is resulting in changes in behavior and social norms as well as increased levels of cyber-crime.

Today social networks are becoming the platform of choice for hackers and other perpetrators of antisocial behavior. These media offer large volumes of data/information ranging from an individual’s date of birth, place of residence, place of work/business, to information about family and other personal activities. In many cases users unintentionally disclose information that can be both dangerous and inappropriate. Information regarding activities on social media can have far reaching negative implications for one’s future. A few examples of situations which can, and have been affected are employment, visa acquisition, and college acceptance. Indiscriminate participation has also resulted in situations such identity theft and bank fraud just to list a few. Protecting privacy in today’s networked society can be a great challenge. The digital revolution has indeed distorted our views of privacy, however, there should be clear distinctions between what should be seen by the general public and what should be limited to a selected group. One school of thought is that the only way to have privacy today is not to share information in these networked communities. However, achieving privacy and control over information flows and disclosure in networked communities is an ongoing process in an environment where contexts change quickly and are sometimes blurred. This requires intentional construction of systems that are designed to mitigate privacy issues [ 13 ].

5. Ethics and social media

Can this post be regarded as oversharing?

Has the information in this post been distorted in anyway?

What impact will this post have on others?

As previously mentioned, users within the ages 8–15 represent one of the largest social media user groups. These young persons within the 8–15 age range are still learning how to interact with the people around them and are deciding on the moral values that they will embrace. These moral values will help to dictate how they will interact with the world around them. The ethical values that guide our interactions are usually formulated from some moral principle taught to us by someone or a group of individuals including parents, guardians, religious groups, and teachers just to name a few. Many of the Gen Y’s/“Digital Babies” are “newbies” yet are required to determine for themselves the level of responsibility they will display when using the varying social media platforms. This includes considering the impact a post will have on their lives and/or the lives of other persons. They must also understand that when they join a social media network, they are joining a community in which certain behavior must be exhibited. Such responsibility requires a much greater level of maturity than can be expected from them at that age.

It is not uncommon for individuals to post even the smallest details of their lives from the moment they wake up to when they go to bed. They will openly share their location, what they eat at every meal or details about activities typically considered private and personal. They will also share likes and dislikes, thoughts and emotional states and for the most part this has become an accepted norm. Often times however, these shares do not only contain information about the person sharing but information about others as well. Many times, these details are shared on several social media platforms as individuals attempt to ensure that all persons within their social circle are kept updated on their activities. With this openness of sharing risks and challenges arise that are often not considered but can have serious impacts. The speed and scale with which social media creates information and makes it available—almost instantaneously—on a global scale, added to the fact that once something is posted there is really no way of truly removing it, should prompt individuals to think of the possible impact a post can have. Unfortunately, more often than not, posts are made without any thought of the far-reaching impact they can have on the lives of the person posting or others that may be implicated by the post.

6. Why do people share?

cause related

personal connection to content

to feel more involved in the world

to define who they are

to inform and entertain

People generally share because they believe that what they are sharing is important. It is hoped that the shared content will be deemed important to others which will ultimately result in more shares, likes and followers.

Figure 1 below sums up the findings of Berger and Milkman [ 25 ] which shows that the main reason people feel the need to share content on the varying social media platform is that the content relates to what is deemed as worthy cause. 84% of respondents highlighted this as the primary motivation for sharing. Seventy-eight percent said that they share because they feel a personal connection to the content while 69 and 68%, respectively said the content either made them feel more involved with the world or helped them to define who they were. Forty-nine percent share because of the entertainment or information value of the content. A more in depth look at each reason for sharing follows.

Why people share source: Global Social Media Research. thesocialmediahat.com [ 26 ].

7. Content related to a cause

Social media has provided a platform for people to share their thoughts and express concerns with others for what they regard as a worthy cause. Cause related posts are dependent on the interest of the individual. Some persons might share posts related to causes and issues happening in society. In one example, the parents of a baby with an aggressive form of leukemia, who having been told that their child had only 3 months to live unless a suitable donor for a blood stem cell transplant could be found, made an appeal on social media. The appeal was quickly shared and a suitable donor was soon found. While that was for a good cause, many view social media merely as platforms for freedom of speech because anyone can post any content one creates. People think the expression of their thoughts on social media regarding any topic is permissible. The problem with this is that the content may not be accepted by law or it could violate the rights of someone thus giving rise to ethical questions.

8. Content with a personal connection

When social media users feel a personal connection to their content, they are more inclined to share the content within their social circles. This is true of information regarding family and personal activities. Content created by users also invokes a deep feeling of connection as it allows the users to tell their stories and it is natural to want the world or at least friends to know of the achievement. This natural need to share content is not new as humans have been doing this in some form or the other, starting with oral history to the media of the day; social media. Sharing the self-created content gives the user the opportunity of satisfying some fundamental needs of humans to be heard, to matter, to be understood and emancipated. The problem with this however is that in an effort to gratify the fundamental needs, borders are crossed because the content may not be sharable (can this content be shared within the share network?), it may not be share-worthy (who is the audience that would appreciate this content?) or it may be out of context (does the content fit the situation?).

9. Content that makes them feel more involved in the world

One of the driving factors that pushes users to share content is the need to feel more in tune with the world around them. This desire is many times fueled by jealousy. Many social media users are jealous when their friends’ content gets more attention than their own and so there is a lot of pressure to maintain one’s persona in social circles, even when the information is unrealistic, as long as it gets as much attention as possible. Everything has to be perfect. In the case of a photo, for example, there is lighting, camera angle and background to consider. This need for perfection puts a tremendous amount of pressure on individuals to ensure that posted content is “liked” by friends. They often give very little thought to the amount of their friend’s work that may have gone on behind the scenes to achieve that perfect social post.

Social media platforms have provided everyone with a forum to express views, but, as a whole, conversations are more polarized, tribal and hostile. With Facebook for instance, there has been a huge uptick in fake news, altered images, dangerous health claims and cures, and the proliferation of anti-science information. This is very distressing and disturbing because people are too willing to share and to believe without doing their due diligence and fact-checking first.

10. Content that defines who they are

Establishing one’s individuality in society can be challenging for some persons because not everyone wants to fit in. Some individuals will do all they can to stand out and be noticed. Social media provides the avenue for exposure and many individuals will seek to leverage the media to stand out of the crowd and not just be a fish in the school. Today many young people are currently being brought up in a culture that defines people by their presence on social media where in previous generations, persons were taught to define themselves by their career choices. These lessons would start from childhood by asking children what they wanted to be when they grew up and then rewarding them based on the answers they give [ 27 ]. In today’s digital era, however, social media postings and the number of “likes” or “dislikes” they attract, signal what is appealing to others. Therefore, post that are similar to those that receive a large number of likes but which are largely unrealistic are usually made for self-gratification.

11. Content that informs and entertains

The acquisition of knowledge and skills is a vital part of human survival and social media has made this process much easier. It is not uncommon to hear persons realizing that they need a particular knowledge set that they do not possess say “I need to lean to do this. I’ll just YouTube it.” Learning and adapting to change in as short as possible time is vital in today’s society and social media coupled with the Internet put it all at the finger tips. Entertainment has the ability to bring people together and is a good way for people to bond. It provides a diversion from the demands of life and fills leisure time with amusement. Social media is an outlet for fun, pleasurable and enjoyable activities that are so vital to human survival [ 28 ]. It is now common place to see persons watching a video, viewing images and reading text that is amusing on any of the available social media platforms. Quite often these videos, images and texts can be both informative and entertaining, but there can be problems however as at times they can cross ethical lines that can lead to conflict.

12. Ethical challenges with social media use

The use of modern-day technology has brought several benefits. Social media is no different and chief amongst its benefit is the ability to stay connected easily and quickly as well as build relationships with people with similar interests. As with all technology, there are several challenges that can make the use of social media off putting and unpleasant. Some of these challenges appear to be minor but they can have far reaching effects into the lives of the users of social media and it is therefore advised that care be taken to minimize the challenges associated with the use of social media [ 29 ].

A major challenge with the use of social media is oversharing because when persons share on social media, they tend to share as much as is possible which is often times too much [ 24 ]. When persons are out and about doing exciting things, it is natural to want to share this with the world as many users will post a few times a day when they head to lunch, visit a museum, go out to dinner or other places of interest [ 30 ]. While this all seems relatively harmless, by using location-based services which pinpoint users with surprising accuracy and in real time, users place themselves in danger of laying out a pattern of movement that can be easily traced. While this seems more like a security or privacy issue it stems from an ethical dilemma—“Am I sharing too much?” Oversharing can also lead to damage of user’s reputation especially if the intent is to leverage the platform for business [ 24 ]. Photos of drunken behavior, drug use, partying or other inappropriate content can change how you are viewed by others.

Another ethical challenge users of social media often encounter is that they have no way of authenticating content before sharing, which becomes problematic when the content paints people or establishments negatively. Often times content is shared with them by friends, family and colleagues. The unauthenticated content is then reshared without any thought but sometimes this content may have been maliciously altered so the user unknowingly participates in maligning others. Even if the content is not altered the fact that the content paints someone or something in a bad light should send off warning bells as to whether or not it is right to share the content which is the underlying principle of ethical behavior.

13. Conflicting views

Some of the challenges experienced by social media posts are a result of a lack of understanding and sometimes a lack of respect for the varying ethical and moral standpoints of the people involved. We have established that it is typical for persons to post to social media sites without any thought as to how it can affect other persons, but many times these posts are a cause of conflict because of a difference of opinion that may exist and the effect the post may have. Each individual will have his or her own ethical values and if they differ then this can result in conflict [ 31 ]. When an executive of a British company made an Instagram post with some racial connotations before boarding a plane to South Africa it started a frenzy that resulted in the executive’s immediate dismissal. Although the executive said it was a joke and there was no prejudice intended, this difference in views as to the implications of the post, resulted in an out of work executive and a company scrambling to maintain its public image.

14. Impact on personal development

In this age of sharing, many young persons spend a vast amount of time on social media checking the activities of their “friends” as well as posting on their own activities so their “friends” are aware of what they are up to. Apart from interfering with their academic progress, time spent on these posts at can have long term repercussions. An example is provided by a student of a prominent university who posted pictures of herself having a good time at parties while in school. She was denied employment because of some of her social media posts. While the ethical challenge here is the question of the employee’s right to privacy and whether the individual’s social media profile should affect their ability to fulfill their responsibilities as an employee, the impact on the individual’s long term personal growth is clear.

15. Conclusion

In today’s information age, one’s digital footprint can make or break someone; it can be the deciding factor on whether or not one achieves one’s life-long ambitions. Unethical behavior and interactions on social media can have far reaching implications both professionally and socially. Posting on the Internet means the “end of forgetting,” therefore, responsible use of this medium is critical. The unethical use of social media has implications for privacy and can result in security breaches both physically and virtually. The use of social media can also result in the loss of privacy as many users are required to provide information that they would not divulge otherwise. Social media use can reveal information that can result in privacy breaches if not managed properly by users. Therefore, educating users of the risks and dangers of the exposure of sensitive information in this space, and encouraging vigilance in the protection of individual privacy on these platforms is paramount. This could result in the reduction of unethical and irresponsible use of these media and facilitate a more secure social environment. The use of social media should be governed by moral and ethical principles that can be applied universally and result in harmonious relationships regardless of race, culture, religious persuasion and social status.

Analysis of the literature and the findings of this research suggest achieving acceptable levels of privacy is very difficult in a networked system and will require much effort on the part of individuals. The largest user groups of social media are unaware of the processes that are required to reduce the level of vulnerability of their personal data. Therefore, educating users of the risk of participating in social media is the social responsibility of these social network platforms. Adapting universally ethical behaviors can mitigate the rise in the number of privacy breaches in the social networking space. This recommendation coincides with philosopher Immanuel Kant’s assertion that, the Biblical principle which states “Do unto others as you have them do unto you” can be applied universally and should guide human interactions [ 5 ]. This principle, if adhered to by users of social media and owners of these platforms could raise the awareness of unsuspecting users, reduce unethical interactions and undesirable incidents that could negatively affect privacy, and by extension security in this domain.

- 1. Chaffey D. Global Social Media Research. Smart Insights. 2019. Retrieved from: https://www.smartinsights.com/social-media-marketing/social-media-strategy/new-global-social-media-research/

- 2. SmartSocial. Teen Social Media Statistics (What Parents Need to Know). 2019. Retrieved from: https://smartsocial.com/social-media-statistics/

- 3. Wisniewski P, Jia H, Xu H, Rosson MB, Carroll JM. Preventative vs. reactive: How parental mediation influences teens’ social media privacy behaviors. In: Proceedings of the 18th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing; ACM; 2015. pp. 302-316

- 4. Chai S, Bagchi-Sen S, Morrell C, Rao HR, Upadhyaya SJ. Internet and online information privacy: An exploratory study of preteens and early teens. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication. 2009; 52 (2):167-182

- 5. Baase S. A Gift of Fire. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Education Limited (Prentice Hall); 2012

- 6. Richards NM, Solove DJ. Prosser’s privacy law: A mixed legacy. California Law Review. 2010; 98 :1887

- 7. Johnson DG. Computer ethics. In: The Blackwell Guide to the Philosophy of Computing and Information. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Education (Prentice Hall); 2004. pp. 65-75

- 8. Cohen JE. What privacy is for. Harvard Law Review. 2012; 126 :1904

- 9. Moore AD. Toward informational privacy rights. San Diego Law Review. 2007; 44 :809

- 10. GOVTECH. Singapore. 2019. Retrieved from: https://www.tech.gov.sg/products-and-services/smart-nation-sensor-platform/

- 11. Weaver AC, Morrison BB. Social networking. Computer. 2008; 41 (2):97-100

- 12. Boulianne S. Social media use and participation: A meta-analysis of current research. Information, Communication and Society. 2015; 18 (5):524-538

- 13. Marwick AE, Boyd D. Networked privacy: How teenagers negotiate context in social media. New Media & Society. 2014; 16 (7):1051-1067

- 14. McCay-Peet L, Quan-Haase A. What is social media and what questions can social media research help us answer. In: The SAGE Handbook of Social Media Research Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publishers; 2017. pp. 13-26

- 15. Gil de Zúñiga H, Jung N, Valenzuela S. Social media use for news and individuals’ social capital, civic engagement and political participation. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 2012; 17 (3):319-336

- 16. Ems L. Twitter’s place in the tussle: How old power struggles play out on a new stage. Media, Culture and Society. 2014; 36 (5):720-731

- 17. Haggart B. Fair copyright for Canada: Lessons for online social movements from the first Canadian Facebook uprising. Canadian Journal of Political Science (Revue canadienne de science politique). 2013; 46 (4):841-861

- 18. Andrews LB. I Know Who You are and I Saw What You Did: Social Networks and the Death of Privacy. Simon and Schuster, Free Press; 2012

- 19. Echaiz J, Ardenghi JR. Security and online social networks. In: XV Congreso Argentino de Ciencias de la Computación. 2009

- 20. Barrett-Maitland N, Barclay C, Osei-Bryson KM. Security in social networking services: A value-focused thinking exploration in understanding users’ privacy and security concerns. Information Technology for Development. 2016; 22 (3):464-486

- 21. Van Der Velden M, El Emam K. “Not all my friends need to know”: A qualitative study of teenage patients, privacy, and social media. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2013; 20 (1):16-24

- 22. Bolton RN, Parasuraman A, Hoefnagels A, Migchels N, Kabadayi S, Gruber T, et al. Understanding Generation Y and their use of social media: A review and research agenda. Journal of Service Management. 2013; 24 (3):245-267

- 23. Cohn C. Social Media Ethics and Etiquette. CompuKol Communication LLC. 20 March 2010. Retrieved from: https://www.compukol.com/social-media-ethics-and-etiquette/

- 24. Nates C. The Dangers of Oversharing of Social Media. Pure Moderation. 2018. Retrieved from: https://www.puremoderation.com/single-post/The-Dangers-of-Oversharing-on-Social-Media

- 25. Berger J, Milkman K. What makes online content go viral. Journal of Marketing Research. 2011; 49 (2):192-205

- 26. The Social Media Hat. How to Find Amazing Content for Your Social Media Calendar (And Save Yourself Tons of Work). 29 August 2016. Retrieved from: https://www.thesocialmediahat.com/blog/how-to-find-amazing-content-for-your-social-media-calendar-and-save-yourself-tons-of-work/

- 27. People First. Does what you do define who you are. 15 September 2012. Retrieved from: https://blog.peoplefirstps.com/connect2lead/what-you-do-define-you

- 28. Dreyfus E. Does what you do define who you are. Psychologically Speaking. 2010. Retrieved from: https://www.edwarddreyfusbooks.com/psychologically-speaking/does-what-you-do-define-who-you-are/

- 29. Business Ethics Briefing. The Ethical Challenges and Opportunities of Social Media Use. (Issue 66). 2019. Retrieved from: https://www.ibe.org.uk/userassets/briefings/ibe_social_media_briefing.pdf

- 30. Staff Writer. The consequences of oversharing on social networks. Reputation Defender. 2018. Retrieved from: https://www.reputationdefender.com/blog/social-media/consequences-oversharing-social-networks

- 31. Business Ethics Briefing. The Ethical Challenges of Social Media. (Issue 22). 2011. Retrieved from: https://www.ibe.org.uk/userassets/briefings/ibe_briefing_22_the_ethical_challenges_of_social_media.pdf

© 2020 The Author(s). Licensee IntechOpen. This chapter is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Continue reading from the same book

Edited by Christos Kalloniatis

Published: 09 September 2020

By Ebru Celikel Cankaya

1106 downloads

By Aikaterini-Georgia Mavroeidi, Angeliki Kitsiou and...

969 downloads

By Bata Krishna Tripathy

1395 downloads

IntechOpen Author/Editor? To get your discount, log in .

Discounts available on purchase of multiple copies. View rates

Local taxes (VAT) are calculated in later steps, if applicable.

Support: [email protected]

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

- Teens, Social Media, and Privacy

Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Part 1: Teens and Social Media Use

- Part 2: Information Sharing, Friending, and Privacy Settings on Social Media

- Part 3: Reputation Management on Social Media

- Part 4: Putting Privacy Practices in Context: A Portrait of Teens’ Experiences Online

Teens share a wide range of information about themselves on social media sites; 1 indeed the sites themselves are designed to encourage the sharing of information and the expansion of networks. However, few teens embrace a fully public approach to social media. Instead, they take an array of steps to restrict and prune their profiles, and their patterns of reputation management on social media vary greatly according to their gender and network size. These are among the key findings from a new report based on a survey of 802 teens that examines teens’ privacy management on social media sites:

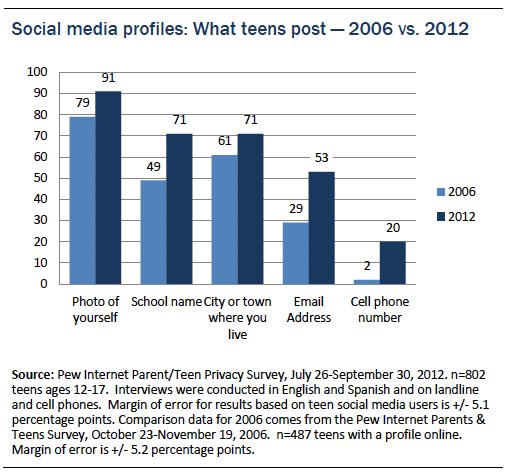

- Teens are sharing more information about themselves on social media sites than they did in the past. For the five different types of personal information that we measured in both 2006 and 2012, each is significantly more likely to be shared by teen social media users in our most recent survey.

Teen Twitter use has grown significantly: 24% of online teens use Twitter, up from 16% in 2011.

The typical (median) teen facebook user has 300 friends, while the typical teen twitter user has 79 followers..

- Focus group discussions with teens show that they have waning enthusiasm for Facebook, disliking the increasing adult presence, people sharing excessively, and stressful “drama,” but they keep using it because participation is an important part of overall teenage socializing.

60% of teen Facebook users keep their profiles private, and most report high levels of confidence in their ability to manage their settings.

Teens take other steps to shape their reputation, manage their networks, and mask information they don’t want others to know; 74% of teen social media users have deleted people from their network or friends list., teen social media users do not express a high level of concern about third-party access to their data; just 9% say they are “very” concerned., on facebook, increasing network size goes hand in hand with network variety, information sharing, and personal information management..

- In broad measures of online experience, teens are considerably more likely to report positive experiences than negative ones. For instance, 52% of online teens say they have had an experience online that made them feel good about themselves.

Teens are sharing more information about themselves on social media sites than they did in the past.

Teens are increasingly sharing personal information on social media sites, a trend that is likely driven by the evolution of the platforms teens use as well as changing norms around sharing. A typical teen’s MySpace profile from 2006 was quite different in form and function from the 2006 version of Facebook as well as the Facebook profiles that have become a hallmark of teenage life today. For the five different types of personal information that we measured in both 2006 and 2012, each is significantly more likely to be shared by teen social media users on the profile they use most often.

- 91% post a photo of themselves , up from 79% in 2006.

- 71% post their school name , up from 49%.

- 71% post the city or town where they live , up from 61%.

- 53% post their email address , up from 29%.

- 20% post their cell phone number , up from 2%.

In addition to the trend questions, we also asked five new questions about the profile teens use most often and found that among teen social media users:

- 92% post their real name to the profile they use most often. 2

- 84% post their interests , such as movies, music, or books they like.

- 82% post their birth date .

- 62% post their relationship status .

- 24% post videos of themselves .

Older teens are more likely than younger teens to share certain types of information, but boys and girls tend to post the same kind of content.

Generally speaking, older teen social media users (ages 14-17), are more likely to share certain types of information on the profile they use most often when compared with younger teens (ages 12-13).

Older teens who are social media users more frequently share:

- Photos of themselves on their profile (94% older teens vs. 82% of younger teens)

- Their school name (76% vs. 56%)

- Their relationship status (66% vs. 50%)

- Their cell phone number (23% vs. 11%)

While boys and girls generally share personal information on social media profiles at the same rates, cell phone numbers are a key exception. Boys are significantly more likely to share their numbers than girls (26% vs. 14%). This is a difference that is driven by older boys. Various differences between white and African-American social media-using teens are also significant, with the most notable being the lower likelihood that African-American teens will disclose their real names on a social media profile (95% of white social media-using teens do this vs. 77% of African-American teens). 3

16% of teen social media users have set up their profile to automatically include their location in posts.

Beyond basic profile information, some teens choose to enable the automatic inclusion of location information when they post. Some 16% of teen social media users said they set up their profile or account so that it automatically includes their location in posts. Boys and girls and teens of all ages and socioeconomic backgrounds are equally likely to say that they have set up their profile to include their location when they post. Focus group data suggests that many teens find sharing their location unnecessary and unsafe, while others appreciate the opportunity to signal their location to friends and parents.

Twitter draws a far smaller crowd than Facebook for teens, but its use is rising. One in four online teens uses Twitter in some way. While overall use of social networking sites among teens has hovered around 80%, Twitter grew in popularity; 24% of online teens use Twitter, up from 16% in 2011 and 8% the first time we asked this question in late 2009.

African-American teens are substantially more likely to report using Twitter when compared with white youth.

Continuing a pattern established early in the life of Twitter, African-American teens who are internet users are more likely to use the site when compared with their white counterparts. Two in five (39%) African-American teens use Twitter, while 23% of white teens use the service.

Public accounts are the norm for teen Twitter users.

While those with Facebook profiles most often choose private settings, Twitter users, by contrast, are much more likely to have a public account.

- 64% of teens with Twitter accounts say that their tweets are public, while 24% say their tweets are private.

- 12% of teens with Twitter accounts say that they “don’t know” if their tweets are public or private.

- While boys and girls are equally likely to say their accounts are public, boys are significantly more likely than girls to say that they don’t know (21% of boys who have Twitter accounts report this, compared with 5% of girls).

Overall, teens have far fewer followers on Twitter when compared with Facebook friends; the typical (median) teen Facebook user has 300 friends, while the typical (median) teen Twitter user has 79 followers. Girls and older teens tend to have substantially larger Facebook friend networks compared with boys and younger teens.

Teens’ Facebook friendship networks largely mirror their offline networks. Seven in ten say they are friends with their parents on Facebook.

Teens, like other Facebook users, have different kinds of people in their online social networks. And how teens construct that network has implications for who can see the material they share in those digital social spaces:

- 98% of Facebook-using teens are friends with people they know from school.

- 91% of teen Facebook users are friends with members of their extended family.

- 89% are connected to friends who do not attend the same school.

- 76% are Facebook friends with brothers and sisters.

- 70% are Facebook friends with their parents.

- 33% are Facebook friends with other people they have not met in person.

- 30% have teachers or coaches as friends in their network.

- 30% have celebrities, musicians or athletes in their network.

Older teens tend to be Facebook friends with a larger variety of people, while younger teens are less likely to friend certain groups, including those they have never met in person.

Older teens are more likely than younger ones to have created broader friend networks on Facebook. Older teens (14-17) who use Facebook are more likely than younger teens (12-13) to be connected with:

- Friends who go to different schools (92% vs. 82%)

- People they have never met in person, not including celebrities (36% vs. 25%)

- Teachers or coaches (34% vs. 19%)

Girls are also more likely than boys (37% vs. 23%) to be Facebook friends with coaches or teachers, the only category of Facebook friends where boys and girls differ.

African-American youth are nearly twice as likely as whites to be Facebook friends with celebrities, athletes, or musicians (48% vs. 25%).

Focus group discussions with teens show that they have waning enthusiasm for Facebook.

In focus groups, many teens expressed waning enthusiasm for Facebook. They dislike the increasing number of adults on the site, get annoyed when their Facebook friends share inane details, and are drained by the “drama” that they described as happening frequently on the site. The stress of needing to manage their reputation on Facebook also contributes to the lack of enthusiasm. Nevertheless, the site is still where a large amount of socializing takes place, and teens feel they need to stay on Facebook in order to not miss out.

Users of sites other than Facebook express greater enthusiasm for their choice.

Those teens who used sites like Twitter and Instagram reported feeling like they could better express themselves on these platforms, where they felt freed from the social expectations and constraints of Facebook. Some teens may migrate their activity and attention to other sites to escape the drama and pressures they find on Facebook, although most still remain active on Facebook as well.

Teens have a variety of ways to make available or limit access to their personal information on social media sites. Privacy settings are one of many tools in a teen’s personal data management arsenal. Among teen Facebook users, most choose private settings that allow only approved friends to view the content that they post.

Most keep their Facebook profile private. Girls are more likely than boys to restrict access to their profiles.

Some 60% of teens ages 12-17 who use Facebook say they have their profile set to private, so that only their friends can see it. Another 25% have a partially private profile, set so that friends of their friends can see what they post. And 14% of teens say that their profile is completely public. 4

- Girls who use Facebook are substantially more likely than boys to have a private (friends only) profile (70% vs. 50%).

- By contrast, boys are more likely than girls to have a fully public profile that everyone can see (20% vs. 8%).

Most teens express a high level of confidence in managing their Facebook privacy settings.

More than half (56%) of teen Facebook users say it’s “not difficult at all” to manage the privacy controls on their Facebook profile, while one in three (33%) say it’s “not too difficult.” Just 8% of teen Facebook users say that managing their privacy controls is “somewhat difficult,” while less than 1% describe the process as “very difficult.”

Teens’ feelings of efficacy increase with age:

- 41% of Facebook users ages 12-13 say it is “not difficult at all” to manage their privacy controls, compared with 61% of users ages 14-17.

- Boys and girls report similar levels of confidence in managing the privacy controls on their Facebook profile.

For most teen Facebook users, all friends and parents see the same information and updates on their profile.

Beyond general privacy settings, teen Facebook users have the option to place further limits on who can see the information and updates they post. However, few choose to customize in that way: Among teens who have a Facebook account, only 18% say that they limit what certain friends can see on their profile. The vast majority (81%) say that all of their friends see the same thing on their profile. 5 This approach also extends to parents; only 5% of teen Facebook users say they limit what their parents can see.

Teens are cognizant of their online reputations, and take steps to curate the content and appearance of their social media presence. For many teens who were interviewed in focus groups for this report, Facebook was seen as an extension of offline interactions and the social negotiation and maneuvering inherent to teenage life. “Likes” specifically seem to be a strong proxy for social status, such that teen Facebook users will manipulate their profile and timeline content in order to garner the maximum number of “likes,” and remove photos with too few “likes.”

Pruning and revising profile content is an important part of teens’ online identity management.

Teen management of their profiles can take a variety of forms – we asked teen social media users about five specific activities that relate to the content they post and found that:

- 59% have deleted or edited something that they posted in the past.

- 53% have deleted comments from others on their profile or account.

- 45% have removed their name from photos that have been tagged to identify them.

- 31% have deleted or deactivated an entire profile or account.

- 19% have posted updates, comments, photos, or videos that they later regretted sharing.

74% of teen social media users have deleted people from their network or friends’ list; 58% have blocked people on social media sites.

Given the size and composition of teens’ networks, friend curation is also an integral part of privacy and reputation management for social media-using teens. The practice of friending, unfriending, and blocking serve as privacy management techniques for controlling who sees what and when. Among teen social media users:

- Girls are more likely than boys to delete friends from their network (82% vs. 66%) and block people (67% vs. 48%).

- Unfriending and blocking are equally common among teens of all ages and across all socioeconomic groups.

- 58% of teen social media users say they share inside jokes or cloak their messages in some way.