- A-Z Publications

Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior

Volume 11, 2024, review article, open access, global talent management: a critical review and research agenda for the new organizational reality.

- Paula M. Caligiuri 1 , David G. Collings 2 , Helen De Cieri 3 , and Mila B. Lazarova 4,5

- View Affiliations Hide Affiliations Affiliations: 1 D'Amore McKim School of Business, Northeastern University, Boston, Massachusetts; email: [email protected] 2 Trinity Business School, Trinity College Dublin, the University of Dublin, Dublin, Ireland 3 Monash Business School, Monash University, Caulfield East, Victoria, Australia 4 Beedie School of Business, Simon Fraser University, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada 5 Department of Management, Vienna University of Economics and Business, Vienna, Austria

- Vol. 11:393-421 (Volume publication date January 2024) https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-111821-033121

- Copyright © 2024 by the author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. See credit lines of images or other third-party material in this article for license information

Global talent management (GTM) refers to management activities in a multinational enterprise (MNE) that focus on attracting, motivating, deploying, and retaining high performing and/or high potential employees in strategic roles across a firm's global operations. Despite the critical importance for individual and firm outcomes, scholarly analysis and understanding lack synthesis, and there is limited evidence that MNEs are managing their talent effectively on a global scale. In this article, we review the GTM literature and identify the challenges of implementing GTM in practice. We explore how GTM is aligned with MNE strategy, examine how talent pools are identified, and highlight the role of global mobility. We discuss GTM at the macro level, including the exogenous factors that impact talent management and the outcomes of GTM at various levels. Finally, we identify some emerging challenges and opportunities for the future of GTM.

Article metrics loading...

Full text loading...

Literature Cited

- Aguinis H , O'Boyle E Jr. 2014 . Star performers in twenty-first century organizations. Pers. Psychol. 67 : 2 313– 50 [Google Scholar]

- Aguinis H , O'Boyle E Jr. , Gonzalez-Mulé E , Joo H. 2016 . Cumulative advantage: conductors and insulators of heavy-tailed productivity distributions and productivity stars. Pers. Psychol. 69 : 1 3– 66 [Google Scholar]

- Allen DG , Vardaman JM 2021 . Global Talent Retention: Understanding Employee Turnover Around the World West Yorkshire, UK: Emerald Publ [Google Scholar]

- Andersson U , Forsgren M , Holm U. 2001 . Subsidiary embeddedness and competence development in MNCs: a multi-level analysis. Organ. Stud. 22 : 6 1013– 34 [Google Scholar]

- Asgari E , Hunt RA , Lerner DA , Townsend DM , Hayward ML , Kiefer K. 2021 . Red giants or black holes? The antecedent conditions and multilevel impacts of star performers. Acad. Manag. Ann. 15 : 1 223– 65 [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett CA , Ghoshal S. 1989 . Managing Across Borders: The Transnational Solution Boston: Harvard Bus. Sch. Press, 2nd ed. [Google Scholar]

- Beck JW , Beatty AS , Sackett PR. 2014 . On the distribution of job performance: the role of measurement characteristics in observed departures from normality. Pers. Psychol. 67 : 3 531– 66 [Google Scholar]

- Becker BE , Huselid MA. 2006 . Strategic human resources management: Where do we go from here?. J. Manag. 32 : 6 898– 925 [Google Scholar]

- Becker BE , Huselid MA , Beatty RW. 2009 . The Differentiated Workforce: Translating Talent into Strategic Impact Boston: Harvard Bus. Press [Google Scholar]

- Björkman I , Ehrnrooth M , Mäkelä K , Smale A , Sumelius J. 2013 . Talent or not? Employee reactions to talent identification. Hum. Resour. Manag. 52 : 2 195– 214 [Google Scholar]

- Björkman I , Smale A , Sumelius J , Suutari V , Lu Y. 2008 . Changes in institutional context and MNC operations in China: subsidiary HRM practices in 1996 versus 2006. Int. Bus. Rev. 17 : 2 146– 58 [Google Scholar]

- Bonneton D , Schworm SK , Festing M , Muratbekova-Touron M. 2022 . Do global talent management programs help to retain talent? A career-related framework. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 33 : 2 203– 38 [Google Scholar]

- Bowman C , Hird M. 2014 . A resource-based view of talent management. Strategic Talent Management: Contemporary Issues in International Context P Sparrow, H Scullion, I Tarique 73– 86 Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Browne O. 2020 . How Covid-19 has affected global mobility. ECA International Aug. 11. https://www.eca-international.com/insights/articles/august-2020/how-covid-19-has-affected-global-mobility [Google Scholar]

- Caligiuri P. 2023 . Development of cultural agility competencies through global mobility. J. Glob . Mobil . 11 : 2 145– 58 [Google Scholar]

- Caligiuri P , Caprar DV. 2022 . Becoming culturally agile: effectively varying contextual responses through international experience and cross-cultural competencies. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 34 : 12 2429– 50 [Google Scholar]

- Caligiuri P , De Cieri H , Minbaeva D , Verbeke A , Zimmermann A. 2020 . International HRM insights for navigating the COVID-19 pandemic: implications for future research and practice. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 51 : 697– 713 [Google Scholar]

- Caligiuri P , Mencin A , Jayne B , Traylor A. 2019 . Developing cross-cultural competencies through international corporate volunteerism. J. World Bus. 54 : 1 14– 23 [Google Scholar]

- Caligiuri P , Tarique I. 2016 . Cultural agility and international assignees’ effectiveness in cross-cultural interactions. Int. J. Train. Dev. 20 : 4 280– 89 [Google Scholar]

- Call ML , Nyberg AJ , Thatcher S. 2015 . Stargazing: an integrative conceptual review, theoretical reconciliation, and extension for star employee research. J. Appl. Psychol. 100 : 3 623– 40 [Google Scholar]

- Cappelli P. 2008 . Talent on Demand: Managing Talent in an Age of Uncertainty Boston: Harvard Bus. Sch. Press [Google Scholar]

- Cappelli P , Keller JR. 2014 . Talent management: conceptual approaches and practical challenges. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 1 : 305– 31 [Google Scholar]

- Cappelli P , Keller JR. 2017 . The historical context of talent management. The Oxford Handbook of Talent Management DG Collings, K Mellahi, WF Cascio 23– 40 Oxford, UK: Oxford Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter MA , Sanders WG , Gregersen HB. 2001 . Bundling human capital with organizational context: the impact of international assignment experience on multinational firm performance and CEO pay. Acad. Manag. J. 44 : 3 493– 511 [Google Scholar]

- Cascio WF. 2006 . Global performance management systems. Handbook of Research in International Human Resource Management I Björkman, GK Stahl 176– 96 Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar [Google Scholar]

- Cascio WF , Boudreau JW. 2016 . The search for global competence: from international HR to talent management. J. World Bus. 51 : 1 103– 14 [Google Scholar]

- Cerdin J-L , Brewster C. 2014 . Talent management and expatriation: bridging two streams of research and practice. J. World Bus. 49 : 245– 52 [Google Scholar]

- Chung CC , Park HY , Lee JY , Kim K. 2015 . Human capital in multinational enterprises: Does strategic alignment matter?. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 46 : 806– 29 [Google Scholar]

- Collings DG. 2014 . Toward mature talent management: beyond shareholder value. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 25 : 3 301– 19 [Google Scholar]

- Collings DG , McDonnell A , Gunnigle P , Lavelle J. 2010 . Swimming against the tide: outward staffing flows from multinational subsidiaries. Hum. Resour. Manag. 49 : 4 575– 98 [Google Scholar]

- Collings DG , McMackin J. 2021 . The practices that set learning organizations apart. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev 62 : 4 54 – 59 [Google Scholar]

- Collings DG , Mellahi K. 2009 . Strategic talent management: a review and research agenda. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 19 : 4 304– 13 [Google Scholar]

- Collings DG , Mellahi K , Cascio WF. 2019 . Global talent management and performance in multinational enterprises: a multilevel perspective. J. Manag. 45 : 2 540– 66 [Google Scholar]

- Collings DG , Minbaeva DB. 2021 . Building microfoundations for talent management. The Routledge Companion to Talent Management I Tarique 32– 43 New York: Routledge [Google Scholar]

- Collings DG , Sheeran R. 2020 . Research insights: global mobility in a post-covid world. Ir. J. Manag. 39 : 2 77– 84 [Google Scholar]

- Cooke FL , Saini DS , Wang J. 2014 . Talent management in China and India: a comparison of management perceptions and human resource practices. J. World Bus. 49 : 2 225– 35 [Google Scholar]

- Dastin J. 2018 . Amazon scraps secret AI recruiting tool that showed bias against women. Reuters Oct. 11. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-amazon-com-jobs-automation-insight-idUSKCN1MK08G [Google Scholar]

- De Boeck G , Meyers MC , Dries N. 2018 . Employee reactions to talent management: assumptions versus evidence. J. Organ. Behav. 39 : 2 199– 213 [Google Scholar]

- Dragoni L , Oh I-S , Tesluk PE , Moore OA , VanKatwyk P , Hazucha J. 2014 . Developing leaders’ strategic thinking through global work experience: the moderating role of cultural distance. J. Appl. Psychol. 99 : 5 867– 82 [Google Scholar]

- Earley PC. 2002 . Redefining interactions across cultures and organizations: moving forward with cultural intelligence. Res. Org. Behav. 24 : 271– 99 [Google Scholar]

- Edström A , Galbraith JR. 1977 . Transfer of managers as a coordination and control strategy in multinational organizations. Adm. Sci. Q. 22 : 2 248– 63 [Google Scholar]

- Evans P , Rodriguez-Montemayor E , Lanvin B. 2021 . Talent competitiveness: a framework for macro talent management. The Routledge Companion to Talent Management I Tarique 109– 126 New York: Routledge [Google Scholar]

- Ewerlin D. 2013 . The influence of global talent management on employer attractiveness: an experimental study. Ger. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 27 : 3 279– 304 [Google Scholar]

- Express Employment Professionals 2022 . Many U.S. companies find productivity not negatively impacted by remote work. American Employed Dec. 14. www.expresspros.com/Newsroom/America-Employed/Many-US-Companies-Find-Productivity-Not-Negatively-Impacted-by-Remote-Work.aspx?&referrer=http://www.expresspros.com/americaemployed/ [Google Scholar]

- EY 2021 . More than half of employees globally would quit their jobs if not provided postpandemic flexibility, EY survey finds Press Release, EY May 12. https://www.ey.com/en_us/news/2021/05/more-than-half-of-employees-globally-would-quit-their-jobs-if-not-provided-post-pandemic-flexibility-ey-survey-finds [Google Scholar]

- Farh CIC , Bartol KM , Shapiro DL , Shin J. 2010 . Networking abroad: a process model of how expatriates form support ties to facilitate adjustment. Acad. Manag. Rev. 35 : 3 434– 54 [Google Scholar]

- Farndale E , Pai A , Sparrow P , Scullion H. 2014 . Balancing individual and organizational goals in global talent management: a mutual-benefits perspective. J. World Bus. 49 : 2 204– 14 [Google Scholar]

- Farndale E , Scullion H , Sparrow P. 2010 . The role of the corporate HR function in global talent management. J. World Bus. 45 : 2 161– 68 [Google Scholar]

- Farndale E , Thite M , Budhwar P , Kwon B. 2021 . Deglobalization and talent sourcing: cross-national evidence from high-tech firms. Hum. Resour. Manag. 60 : 2 259– 72 [Google Scholar]

- Feldman DC , Bolino MC. 1999 . The impact of on-site mentoring on expatriate socialization: a structural equation modeling approach. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 10 : 1 54– 71 [Google Scholar]

- Franzino M , Guarino A , Binvel Y , Laouchez J-M. 2023 . The $8.5 trillion talent shortage Rep. Korn Ferry This Week Leadersh. LA: [Google Scholar]

- Furuya N , Stevens MJ , Bird A , Oddou G , Mendenhall M. 2009 . Managing the learning and transfer of global management competence: antecedents and outcomes of Japanese repatriation effectiveness. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 40 : 2 200– 15 [Google Scholar]

- Galma K , Ruffino G , Roulet T. 2022 . 4 experts on how leaders can best respond to a changing global landscape. World Economic Forum June 16. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/06/young-global-leaders-lead-differently-changing-global-landscape/ [Google Scholar]

- Garavan TN. 2012 . Global talent management in science-based firms: an exploratory investigation of the pharmaceutical industry during the global downturn. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 23 : 12 2428– 49 [Google Scholar]

- Garavan TN , Morley MJ , Cross C , Carbery R , Darcy C. 2021 . Tensions in talent: a micro practice perspective on the implementation of high potential talent development programs in multinational corporations. Hum. Resour. Manag. 60 : 273– 93 [Google Scholar]

- Grote D. 2005 . Forced Ranking: Making Performance Management Work Boston: Harvard Bus. Sch. Press [Google Scholar]

- Harzing AW. 2000 . An empirical analysis and extension of the Bartlett and Ghoshal typology of multinational companies. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 31 : 1 101– 20 [Google Scholar]

- Harzing AW. 2001 . Who's in charge? An empirical study of executive staffing practices in foreign subsidiaries. Hum. Resour. Manag. 40 : 2 139– 58 [Google Scholar]

- Harzing AW. 2002 . Of bears, bumble-bees, and spiders: the role of expatriates in controlling foreign subsidiaries. J. World Bus. 36 : 4 366– 79 [Google Scholar]

- Huselid MA , Becker BE , Beatty RW. 2005 . The Workforce Scorecard: Managing Human Capital to Execute Strategy Boston: Harvard Bus. Press [Google Scholar]

- Jokinen T , Brewster C , Suutari V. 2008 . Career capital during international work experiences: contrasting self-initiated expatriate experiences and assigned expatriation. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 19 : 6 979– 98 [Google Scholar]

- Jooss S , Burbach R , Ruël H. 2021 . Examining talent pools as a core talent management practice in multinational corporations. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 32 : 11 2321– 52 [Google Scholar]

- Kabwe C , Okorie C. 2019 . The efficacy of talent management in international business: the case of European multinationals. Thunderbird Int. Bus. Rev. 61 : 6 857– 72 [Google Scholar]

- Kaliannan M , Darmalinggam D , Dorasamy M , Abraham M. 2023 . Inclusive talent development as a key talent management approach: a systematic literature review. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 33 : 100926 [Google Scholar]

- Kehoe RR , Collings DG , Cascio WF. 2023 . Simply the best? Star performers and high potential employees: critical reflections and a path forward for research and practice. Pers. Psychol. 76 : 2 585– 615 [Google Scholar]

- Keller JR , Kehoe RR , Bidwell M , Collings D , Myer A 2021 . In with the old? Examining when boomerang employees outperform new hires. Acad. Manage. J . 64 : 6 1654– 84 [Google Scholar]

- Khilji SE , Pierre R. 2021 . Global macro talent management: an interdisciplinary approach. The Routledge Companion to Global Talent Management I Tarique 94– 108 New York: Routledge [Google Scholar]

- Khilji SE , Schuler RS. 2017 . Talent management in the global context. The Oxford Handbook of Talent Management D Collings, K Mellahi, W Cascio 399– 419 Oxford, UK: Oxford Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Khilji SE , Tarique I , Schuler RS. 2015 . Incorporating the macro view in global talent management. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 25 : 3 236– 48 [Google Scholar]

- King KA , Vaiman V. 2019 . Enabling effective talent management through a macro-contingent approach: a framework for research and practice. BRQ Bus. Res. Q. 22 : 3 194– 206 [Google Scholar]

- Kostova T. 1999 . Transnational transfer of strategic organizational practices: a contextual perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 24 : 2 308– 24 [Google Scholar]

- Lanvin B , Monteiro F 2022 . Global Talent Competitiveness Index. The Tetonics of Talent: Is the World Drifting Towards Talent Inequalities? Fontainebleau, Fr.: INSEAD, Hum. Cap. Leadersh. Inst., Portulans Inst. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarova M , Caligiuri P , Collings DG , De Cieri H. 2023 . Global work in a rapidly changing world: implications for MNEs and individuals. J. World Bus. 58 : 1 101365 [Google Scholar]

- Lazarova M , Cerdin J-L , Liao Y. 2014 . The internationalism career anchor: a validation study. Int. Stud. Manag. Organ. 44 : 2 9– 33 [Google Scholar]

- Lazarova M , Peretz H , Fried Y. 2017 . Locals know best? Subsidiary HR autonomy and subsidiary performance. J. World Bus. 52 : 1 83– 96 [Google Scholar]

- Lepak DP , Snell SA. 1999 . The human resource architecture: toward a theory of human capital allocation and development. Acad. Manag. Rev. 24 : 1 31– 48 [Google Scholar]

- Lewis RE , Heckman RJ. 2006 . Talent management: a critical review. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 16 : 2 139– 54 [Google Scholar]

- Li X , Froese FJ , Pak YS. 2023 . Promoting knowledge sharing in foreign subsidiaries through global talent management: the roles of local employees’ identification and climate strength. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 34 : 16 3205– 32 [Google Scholar]

- LinkedIn 2021 . Is remote work here to stay in Asia-Pacific?. LinkedIn https://business.linkedin.com/talent-solutions/recruiting-tips/thinkinsights/is-remote-work-here-to-stay [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y , Van Assche A. 2023 . The rise of techno-geopolitical uncertainty: implications of the United States CHIPS and Science Act. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2023 : https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-023-00620-3 [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan A , Toh SM. 2014 . Facilitating expatriate adjustment: the role of advice-seeking from host country nationals. J. World Bus. 49 : 4 476– 87 [Google Scholar]

- Mäkelä K , Björkman I , Ehrnrooth M. 2010 . How do MNCs establish their talent pools? Influences on individuals’ likelihood of being labeled as talent. J. World Bus. 45 : 2 134– 42 [Google Scholar]

- McDonnell A , Lamare R , Gunnigle P , Lavelle J. 2010 . Developing tomorrow's leaders: evidence of global talent management in multinational enterprises. J. World Bus. 45 : 2 150– 60 [Google Scholar]

- McKinsey & Company 2021 . Taking a skills-based approach to building the future workforce. McKinsey & Company Nov. 15. https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/people-and-organizational-performance/our-insights/taking-a-skills-based-approach-to-building-the-future-workforce [Google Scholar]

- McNulty Y , De Cieri H. 2016 . Linking global mobility and global talent management: the role of ROI. Empl. Relat. 38 : 1 8– 30 [Google Scholar]

- McNulty Y , Inkson K. 2013 . Managing Expatriates: A Return on Investment Approach New York: Bus. Expert Press [Google Scholar]

- Mellahi K , Collings DG. 2010 . The barriers to effective global talent management: the example of corporate elites in MNEs. J. World Bus. 45 : 2 143– 49 [Google Scholar]

- Metcalfe BD , Makarem Y , Afiouni F. 2021 . Macro talent management theorizing: transnational perspectives of the political economy of talent formation in the Arab Middle East. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 32 : 1 147– 82 [Google Scholar]

- Michaels E , Handfield-Jones H , Axelrod B. 2001 . The War for Talent Boston: Harvard Bus. Press [Google Scholar]

- Minbaeva D , Collings DG. 2013 . Seven myths of global talent management. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 24 : 9 1762– 76 [Google Scholar]

- Minbaeva D , De Cieri H. 2015 . Strategy and IHRM. The Routledge Companion to International Human Resource Management DG Collings, G Wood, P Caligiuri 13– 28 Abingdon, UK: Routledge [Google Scholar]

- Moeller M , Maley J , Harvey M , Kiessling T. 2016 . Global talent management and inpatriate social capital building: a status inconsistency perspective. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 27 : 9 991– 1012 [Google Scholar]

- Morris S , Snell S , Björkman I. 2016 . An architectural framework for global talent management. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 47 : 723– 47 [Google Scholar]

- Netflix 2023a . Netflix culture-seeking excellence. Netflix https://jobs.netflix.com/culture ; accessed July 4 2023 [Google Scholar]

- Netflix 2023b . Top investor questions. Netflix https://ir.netflix.net/ir-overview/top-investor-questions/default.aspx ; accessed July 4, 2023 [Google Scholar]

- Nijs S , Gallardo-Gallardo E , Dries N , Sels L. 2014 . A multidisciplinary review into the definition, operationalization, and measurement of talent. J. World Bus. 49 : 2 180– 91 [Google Scholar]

- O'Donnell SW. 2000 . Managing foreign subsidiaries: agents of headquarters, or an interdependent network?. Strateg. Manag. J. 21 : 5 525– 48 [Google Scholar]

- Ott DL , Iskhakova M. 2019 . The meaning of international experience for the development of cultural intelligence. Crit. Perspect. Int. Bus. 15 : 4 390– 407 [Google Scholar]

- Pekkala K. 2023 . Digital inclusion and inequalities at work in the age of social media. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. In press. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12488 [Google Scholar]

- Pereira V , Collings DG , Wood G , Mellahi K. 2022 . Evaluating talent management in emerging market economies: societal, firm and individual perspectives. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 33 : 11 2171– 91 [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer J. 2001 . Fighting the war for talent is hazardous to your organization's health. Organ. Dyn. 29 : 4 248– 59 [Google Scholar]

- Ployhart RE , Moliterno TP. 2011 . Emergence of the human capital resource: a multilevel model. Acad. Manag. Rev. 36 : 1 127– 50 [Google Scholar]

- Prudential 2021 . Is this working? A year in, workers adapting to tomorrow's workplace Rep. Prudential Pulse Am. Work. Survey, Morn. Consult. [Google Scholar]

- Pucik V , Bjorkman I , Evans P , Stahl G. 2023 . The Global Challenge . Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publ, 4th ed. [Google Scholar]

- Reiche BS , Harzing A-W , Kraimer M. 2009 . The role of international assignees’ social capital in creating interunit intellectual capital: a cross-level model. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 40 : 509– 26 [Google Scholar]

- Reiche BS , Lee YT , Allen DG. 2019 . Actors, structure, and processes: a review and conceptualization of global work integrating IB and HRM research. J. Manag. 45 : 2 359– 83 [Google Scholar]

- Schuler RS , Jackson SE , Tarique I. 2011 . Global talent management and global talent challenges: strategic opportunities for IHRM. J. World Bus. 46 : 4 506– 16 [Google Scholar]

- Scullion H , Collings D. 2010 . Global Talent Management New York: Routledge [Google Scholar]

- Scullion H , Collings DG , Caligiuri PM. 2010 . Global talent management. J. World Bus. 45 : 2 105– 8 [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro JM , Ozanne JL , Saatcioglu B. 2008 . An interpretive examination of the development of cultural sensitivity in international business. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 39 : 1 71– 87 [Google Scholar]

- SHRM (Soc. Hum. Resour. Manag.) 2020 . 2019 Challenges and benefits of global teams—an HR perspective Rep. SHRM Alexandria, VA: [Google Scholar]

- Sirva BGRS 2022 . Pulse survey: the growth of the employee mobility function. Sirva BGRS https://landing.sirva.com/2022-SIRVA-BGRS-Pulse-Survey-Report.html?utm_source=bgrs-website&utm_medium=content-download [Google Scholar]

- Somaya D , Williamson I , Lorinkova N. 2008 . Gone but not lost: the different performance impacts of employee mobility between cooperators versus competitors. Acad. Manag. J. 51 : 5 936– 53 [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow P , Farndale E , Scullion H. 2013 . An empirical study of the role of the corporate HR function in global talent management in professional and financial service firms in the global financial crisis. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 24 : 9 1777– 98 [Google Scholar]

- Stahl GK , Björkman I , Farndale E , Morris SS , Paauwe J et al. 2012 . Six principles of effective global talent management. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev . 53 : 2 25– 42 [Google Scholar]

- Stahl GK , Brewster CJ , Collings DG , Hajro A. 2020 . Enhancing the role of human resource management in corporate sustainability and social responsibility: a multi-stakeholder, multidimensional approach to HRM. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 30 : 100708 [Google Scholar]

- Suutari V , Taka M. 2004 . Career anchors of managers with global careers. J. Manag. Dev. 23 : 9 833– 47 [Google Scholar]

- Suutari V , Tornikoski C , Mäkelä L. 2012 . Career decision making of global careerists. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 23 : 16 3455– 78 [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi R , Tesluk PE , Yun S , Lepak DP. 2005 . An integrative view of international experience. Acad. Manag. J. 48 : 1 85– 100 [Google Scholar]

- Tan D , Rider CI. 2017 . Let them go? How losing employees to competitors can enhance firm status. Strat. Manag. J. 38 : 9 1848– 74 [Google Scholar]

- Tarique I , Schuler RS. 2010 . Global talent management: literature review, integrative framework, and suggestions for further research. J . World Bus . 45 : 2 122– 33 [Google Scholar]

- Tarique I , Schuler R. 2018 . A multi-level framework for understanding global talent management systems for high talent expatriates within and across subsidiaries of MNEs: propositions for further research. J. Glob. Mobil. 6 : 1 79– 101 [Google Scholar]

- Tharoor I. 2021 . The ‘Great Resignation’ goes global. Washington Post Oct. 18. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2021/10/18/labor-great-resignation-global/ [Google Scholar]

- Tung RL , Paik YS , Bae J. 2013 . Korean human resource management in the global context. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 24 : 5 905– 21 [Google Scholar]

- Vaiman V , Cascio WF , Collings DG , Swider BW. 2021 . The shifting boundaries of talent management. Hum. Resour. Manag. 60 : 2 253– 57 [Google Scholar]

- Vaiman V , Haslberger A , Vance C. 2015 . Recognizing the important role of self-initiated expatriates in effective global talent management. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 25 : 280– 86 [Google Scholar]

- Vardi S , Collings DG. 2023 . What's in a name? Talent: a review and research agenda. Hum . Resour. Manag. J . 33 : 3 660– 82 [Google Scholar]

- Welch D. 2003 . Globalisation of staff movements: beyond cultural adjustment. Manag. Int. Rev. 43 : 2 149– 99 [Google Scholar]

Data & Media loading...

- Article Type: Review Article

Most Read This Month

Most cited most cited rss feed, conservation of resources in the organizational context: the reality of resources and their consequences, self-determination theory in work organizations: the state of a science, burnout and work engagement: the jd–r approach, psychological safety: the history, renaissance, and future of an interpersonal construct, employee voice and silence, psychological capital: an evidence-based positive approach, how technology is changing work and organizations, research on workplace creativity: a review and redirection, abusive supervision, the psychology of entrepreneurship.

- Data, AI, & Machine Learning

- Managing Technology

- Social Responsibility

- Workplace, Teams, & Culture

- AI & Machine Learning

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Big ideas Research Projects

- Artificial Intelligence and Business Strategy

- Responsible AI

- Future of the Workforce

- Future of Leadership

- All Research Projects

- AI in Action

- Most Popular

- The Truth Behind the Nursing Crisis

- Coaching for the Future-Forward Leader

- Measuring Culture

Our summer 2024 issue highlights ways to better support customers, partners, and employees, while our special report shows how organizations can advance their AI practice.

- Past Issues

- Upcoming Events

- Video Archive

- Me, Myself, and AI

- Three Big Points

Six Principles of Effective Global Talent Management

Following talent management best practices can only take you so far. top-performing companies subscribe to a set of principles that are consistent with their strategy and culture..

- Talent Management

- Global Strategy

Internal consistency in talent management practices — in other words, the way a company’s talent management practices fit with each other — is key, as companies such as Siemens recognize.

Image courtesy of Siemens.

One of the biggest challenges facing companies all over the world is building and sustaining a strong talent pipeline. Not only do businesses need to adjust to shifting demographics and work force preferences, but they must also build new capabilities and revitalize their organizations — all while investing in new technologies, globalizing their operations and contending with new competitors. What do companies operating in numerous markets need to do to attract and develop the very best employees so they can be competitive globally? To learn how leading multinational companies are facing up to the talent test, we examined both qualitative and quantitative data at leading companies from a wide range of industries all over the world.

About the Research

This paper is based on a multiyear collaborative research project on global talent management practices and principles by an international team of researchers from INSEAD, Cornell, Cambridge and Tilburg universities. The research looked at 33 multinational corporations, headquartered in 11 countries, and examined 18 companies in depth. We selected the case companies based on their superior business performance and reputations as employers, as defined through Fortune listings and equivalent rankings (e.g., the “Best Companies for Leadership” by the Hay Group and Chief Executive magazine).

The case study interviews were semi-structured, covering questions about the business context, talent management practices and HR function. We interviewed HR professionals and managers and also a sample of executives and line managers in an effort to understand the ways companies source, attract, select, develop, promote and move high-potential employees through the organization. A second stage of research consisted of a Web-based survey of 20 companies. The survey contained items on six key talent management practice areas (staffing, training and development, appraisal, rewards, employee relations, and leadership and succession) and the HR delivery mechanisms (including the use and effectiveness of outsourcing, shared services, Web-based HR, off-shoring and on-shoring). Ultimately, we received a total of 263 complete surveys from the Americas, Asia-Pacific, Europe, the Middle East and Africa.

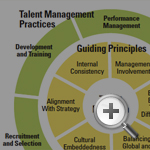

The range of talent management issues facing multinational companies today is extremely broad. Companies must recruit and select talented people, develop them, manage their performance, compensate and reward them and try to retain the strongest performers. Although every organization must pay attention to each of these areas, our research convinced us that competitive advantage in talent management doesn’t just come from identifying key activities (for example, recruiting and training) and then implementing “best practices.” Rather, we found that successful companies adhere to six key principles: (1) alignment with strategy, (2) internal consistency, (3) cultural embeddedness, (4) management involvement, (5) a balance of global and local needs and (6) employer branding through differentiation.

How Companies Define Talent

We use the term “talent management” broadly, recognizing that there is considerable debate within companies about what constitutes “talent” and how it should be managed. 1 (See “The Talent Management Wheel.”)

The Talent Management Wheel

View Exhibit

Since the 1998 publication of McKinsey’s “ War for Talent” study, 2 many managers have considered talent management synonymous with human capital management. Among the companies we studied, there were two distinct views on how best to evaluate and manage talent. One group assumed that some employees had more “value” or “potential” than others, and that, as a result, companies should focus the lion’s share of corporate attention and resources on them; the second group had a more inclusive view, believing that too much emphasis on the top players could damage morale and hurt opportunities to achieve broader gains.

The differentiated approach. Although the practice of sorting employees based on their performance and potential has generated criticism, 3 many companies in our study placed heavy emphasis on high-potential employees. Companies favoring this approach focused most of the rewards, incentives and attention on their top talent (“A players”); gave less recognition, financial rewards and development attention to the bulk of the other employees (“B players”); and worked aggressively to weed out employees who didn’t meet performance expectations and were deemed to have little potential (“C players”). 4 This approach has been popularized by General Electric’s “vitality curve,” which differentiates between the top 20%, the middle 70% and the bottom 10%. The actual definition of “high potential” tends to vary from company to company, but many factor in the employee’s cultural fit and values. Novartis, the Swiss pharmaceutical company, for example, looks at whether someone displays the key values and behaviors the company wants in its future leaders.

The percentage of employees included in the high-potential group also differs across companies. For example, Unilever, the Anglo-Dutch consumer products company, puts 15% of employees from each management level in its high-potential category each year, expecting that they will move to the next management level within five years. Other companies are more selective. Infosys, a global technology services company headquartered in Bangalore, India, limits the high-potential pool to less than 3% of the total work force in an effort to manage expectations and limit potential frustration, productivity loss and harmful attrition.

The Leading Question

What steps can global companies take to ensure that they recruit, develop and deploy the right people?

- Don’t just mimic the practices of other top-performing companies.

- Align talent management practices with your strategy and values.

- Make sure your talent management practices are consistent with one another.

The inclusive approach. Some companies prefer a more inclusive approach and attempt to address the needs of employees at all levels of the organization. 5 For example, when asked how Shell defined talent, Shell’s new head of talent management replied, “I don’t have a definition yet. However, I can assure you that my definition will make it possible for any individual employed by Shell at any level to have the potential to be considered talent.” Under an inclusive approach, talent management tactics used for different groups are based on an assessment of how best to leverage the value that each group of employees can bring to the company. 6

The two philosophies of talent management are not mutually exclusive — many of the companies we studied use a combination of both. Depending on the specific talent pool (such as senior executive, technical expert and early career high-potential), there will usually be different career paths and development strategies. A hybrid approach allows for differentiation, and it skirts the controversial issue of whether some employee groups are intrinsically more valuable than others.

Get Updates on Transformative Leadership

Evidence-based resources that can help you lead your team more effectively, delivered to your inbox monthly.

Please enter a valid email address

Thank you for signing up

Privacy Policy

What We Found

As we looked at the array of talent management practices in the 18 companies we studied, we asked interviewees why they thought their company’s individual practices were effective and valuable. Their responses helped us to formulate six core principles. We recognize that adopting a set of principles rather than best practices challenges current thinking. But best practices are only “best” in the context for which they were designed. The principles, on the other hand, have broad application.

Principle 1: Alignment With Strategy

Corporate strategy is the natural starting point for thinking about talent management. Given the company’s strategy, what kind of talent do we need? For example, GE’s growth strategy is based on five pillars: technological leadership, services acceleration, enduring customer relationships, resource allocation and globalization. But GE’s top management understands that implementing these initiatives may have less to do with strategic planning than with attracting, recruiting, developing and deploying the right people to drive the effort. According to CEO Jeffrey Immelt, the company’s talent management system is its most powerful implementation tool. 7 For instance, to support a renewed focus on technological leadership and innovation, GE began targeting technology skills as a key development requirement during its annual organizational and individual review process, which GE calls Session C. In all business segments, a full block of time was allocated to a review of the business’s engineering pipeline, the organizational structure of its engineering function and an evaluation of the potential of engineering talent. In response to Immelt’s concern that technology-oriented managers were underrepresented in GE’s senior management ranks, the Session C reviews moved more engineers into GE’s senior executive band. Talent management practices also helped to drive and implement GE’s other strategic priorities (for example, establishing a more diverse and internationally experienced management cadre).

In a similar vein, a recent survey of chief human resource officers of large multinationals highlighted another approach to aligning talent management with the business strategy. One HR director wrote:

We have integrated our talent management processes with the business planning process. As each major business area discusses and sets their three-year business goals, they will also be setting their three-year human capital goals and embedding those human capital goals within their business plan. Achievement of these goals will be tracked through our management processes. 8

Strategic flexibility is important, and organizations must be able to adapt to changing business conditions and revamp their talent approach when necessary. For example, Oracle, the hardware and software systems company, found that its objective goal-setting and performance appraisal process was no longer adequate. Management wanted to add some nonfinancial and behavior-based measures to encourage people to focus on team targets, leadership goals and governance. This necessitated a significant overhaul of Oracle’s existing performance management systems, investment in line management capability and overall changes to the mind-set of line managers and employees.

Principle 2 : Internal Consistency

Implementing practices in isolation may not work and can actually be counterproductive. The principle of internal consistency refers to the way the company’s talent management practices fit with each other. Our study shows that consistency is crucial. For example, if an organization invests significantly in developing and training high-potential individuals, it should emphasize employee retention, competitive compensation and career management. It also should empower employees to contribute to the organization and reward them for initiative.

Such combinations of practices will lead to a whole that is more than the sum of its parts. There should also be continuity over time. As one manager at Siemens remarked, “What gives Siemens the edge is the monitoring of consistency between systems: the processes and the metrics must make sense together.” For example, one Siemens division has tied everything related to talent management together in such a way that internal consistency among the various HR elements is virtually guaranteed. The division recruits 10 to 12 graduates per year, assigns the new hires to a learning campus (a network for top new graduates within the division) and assesses them at the development center. Later, the designated employees go through a leadership quality analysis and review procedure, including feedback and performance appraisal, and become part of the mentoring program led by top managers. The whole process is continuously monitored through reviews and linked to the company’s reward systems.

BAE Systems, the defense and security company, places a similar emphasis on consistency. From the time prospective managers arrive at the company, or upon their designation as a member of the leadership cadre, they are continuously tracked for development purposes. Drawing upon data from 360-degree appraisals, behavioral performance feedback and executive evaluations of their input to the business planning process, managers participate in leadership development programs that target the specific needs revealed by the leadership assessments.

The emphasis on consistency is also paramount at IBM, which works hard to assure that its people management systems are consistent across its subsidiaries. To achieve this alignment, IBM combines qualitative and quantitative data collected quarterly to ensure that its practices are consistently introduced and implemented. The company also conducts an HR customer satisfaction survey twice a year to learn how employees are responding to the programs and to detect areas of employee dissatisfaction.

Principle 3: Cultural Embeddedness

Many successful companies consider their corporate culture as a source of sustainable competitive advantage. They make deliberate efforts to integrate their stated core values and business principles into talent management processes such as hiring methods, leadership development activities, performance management systems, and compensation and benefits programs. 9 For example, whereas companies have traditionally focused on job-related skills and experience to select people, some multinationals we studied have expanded their selection criteria to include cultural fit. These companies assess applicants’ personalities and values to determine whether they will be compatible with the corporate culture; the assumption is that formal qualifications are not always the best predictors of performance and retention, and that skills are easier to develop than personality traits, attitudes and values. 10

The furniture retailer IKEA selects applicants using tools that focus on values and cultural fit.

Image courtesy of Flickr user Marco Raaphorst .

IKEA, the Sweden-based furniture retailer, for example, selects applicants using tools that focus on values and cultural fit. Its standard questionnaire downplays skills, experience or academic credentials and instead explores the job applicants’ values and beliefs, which become the basis for screening, interviewing, and training and development. Later, when employees apply internally for leadership positions, the main focus is once again on values in an effort to ensure consistency. IBM likewise subscribes to a strong values-based approach to HR. Not only does IBM hire and promote based on values; it regularly engages employees to ensure that employee values are consistent throughout the company. It does this through “ValuesJam” 11 sessions and regular employee health index surveys. The jam sessions provide time to debate and consider the fundamentals of the values in an effort to make sure that they are not perceived as being imposed from the top.

We found that a strong emphasis on cultural fit and values was common among successful global companies. In evaluating entry-level job applications, Infosys is willing to trade off some immediate skill requirements for a specific job in favor of good cultural fit, the right attitude and what it refers to as “learnability.” In addition to evaluating the applicant’s college record, Infosys puts applicants through an analytical and aptitude test, followed by an extensive interview to assess cultural fit and compatibility with the company’s values.

Rather than selecting employees for attitude and cultural fit, a more common approach to promoting the organization’s core values and behavioral standards is through secondary socialization and training. Standardized induction programs, often accompanied by individualized coaching or mentoring activities, were widely used among the companies that we studied. We found that leading companies used training and development not only to improve employee skills and knowledge but also to manage and reinforce culture. For example, Samsung, the Korea-based semiconductor and mobile phone maker, has specifically geared its training program to provide its employees worldwide with background on the company’s philosophy, values, management principles and employee ethics, regardless of where the employees are located. Management’s goal is not to freeze the existing culture but to have an effective means of supporting change. Several years ago, Samsung’s top management came to realize that in order to become a design-driven company, it needed to let go of its traditional, hierarchical culture and embrace a culture that promotes creativity, empowerment and open communication. By encouraging young designers and managers to challenge their superiors and share their ideas more freely, it hopes to make the transition.

In addition to inculcating core values into young leaders, successful companies often make focused efforts to adapt their talent management practices to the needs of a changing work force. 12 Consider the growing interest in healthy work-life balance. As the number of employees seeking balance between their personal and professional lives has increased, more companies have begun to offer flexible working arrangements in an effort to attract the best talent and retain high-potential employees. For example, Accenture, the consulting and technology services firm, has a work-life balance program that was initially aimed at the career challenges faced by women, but it has since made it available to men as well; among other things, the program features flextime, job sharing, telecommuting and “flybacks” for people working away from their home location. 13 The program has allowed Accenture to significantly reduce its turnover rate among women while also increasing its number of female partners. Internal surveys show that team productivity, job satisfaction and personal motivation among women have improved substantially. Although the number of companies offering such programs is still relatively small, the ranks are growing.

Consistent with an increased emphasis on values, some companies have introduced what might be called “values-based” performance management systems: They assess high-potential employees not only according to what they achieve but also on how they reflect or exemplify shared values. BT, the British telecommunications giant, has implemented a performance management system that looks at employees on two dimensions: the extent to which they achieve their individual performance objectives, and the values and behaviors they displayed to deliver the results. The combined ratings influence a manager’s variable pay. Other companies, too, are realizing the importance of balancing financial success with goals such as sustainability, compliance or social responsibility.

Principle 4: Management Involvement

Successful companies know that the talent management process needs to have broad ownership — not just by HR, but by managers at all levels, including the CEO. Senior leaders need to be actively involved in the talent management process and make recruitment, succession planning, leadership development and retention of key employees their top priorities. They must be willing to devote a significant amount of their time to these activities. A.G. Lafley, former CEO of Procter & Gamble, claims he used to spend one-third to one-half of his time developing talent. He was convinced that “[n]othing I do will have a more enduring impact on P&G’s long-term success than helping to develop other leaders.” 14

However, that level of executive commitment is rare. In a recent survey of chief human resource officers at U.S. Fortune 200 companies, one respondent lamented that the most difficult aspect of the role was

creating a true sense of ownership among the senior leaders regarding their roles as “chief talent officer”; recognizing that having the right people in critical leadership roles is not an HR thing or responsibility, but rather, it is a business imperative and must be truly owned by the leaders of the respective businesses/functions…. Creating this type of mindset around leadership and talent is the biggest challenge I face. 15

One of the most potent tools companies can use to develop leaders is to involve line managers. It means getting them to play a key role in the recruitment of talent and then making them accountable for developing the skills and knowledge of their employees. Unilever, for example, believes in recruiting only the very best people. To make this happen, top-level managers must make time for interviews, even in the face of all their other responsibilities. Line managers can contribute by acting as coaches or mentors, providing job-shadowing opportunities and encouraging talented employees to move around within the organization for career development.

The responsibility for talent development extends beyond managers. Employees need to play an active part themselves by seeking out challenging assignments, cross-functional projects and new positions. However, our survey finds that job rotations across functions or business units are not very common. Although HR managers in our survey saw value in job rotations and new assignments for career development, many companies lack the ability to implement them. A possible explanation is the tendency of managers to focus on the interests of their own units rather than the whole organization; 16 this narrowness may hinder talent mobility and undermine the effectiveness of job rotation as a career development tool. A McKinsey study found that more than 50% of CEOs, business unit leaders and HR executives interviewed believed that insular thinking and a lack of collaboration prevented their talent management programs from delivering business value. 17

Principle 5: Balance of Global and Local Needs

For organizations operating in multiple countries, cultures and institutional environments, talent management is complicated. Companies need to figure out how to respond to local demands while maintaining a coherent HR strategy and management approach. 18 Among the companies we studied, there was no single strategy. For example, Oracle emphasized global integration, with a high degree of centralization and little local discretion. Matsushita, meanwhile, focused on responsiveness to local conditions and allowed local operations to be highly autonomous.

A company’s decision about how much local control to allow depends partly on the industry; for instance, consumer products need to be more attuned to the local market than pharmaceuticals or software. 19 Furthermore, rather than being static, a company’s position may evolve over time in response to internal and external pressures. Our study suggests that many companies are moving toward greater integration and global standards while simultaneously continuing to experience pressure to adapt and make decisions at local levels. For example, Rolls Royce has global standards for process excellence, supported by a global set of shared values and a global talent pool approach for senior executives and high potentials. At the same time, it has to comply with local institutional demands and build local talent pools. Clearly, the challenge for most companies is to be both global and local at the same time. Companies need a global template for talent management to ensure consistency but need to allow local subsidiaries to adapt that template to their specific circumstances. 20

Shell uses one global brand for HR excellence; each business is then able to take that global brand and apply it locally.

Image courtesy of Shell.

Most companies in our sample have introduced global performance standards, supported by global leadership competency profiles and standardized performance appraisal tools and processes. Activities that are seen as less directly linked with the overall strategy of the corporation and/or where local institutional and cultural considerations are viewed as crucial (for example, training and compensation of local staff) continue to be more at the discretion of local management. At IBM, for example, foreign subsidiaries have no choice about whether to use the performance management system; it is used worldwide with only minor adaptations. But subsidiaries may develop other policies and practices to address local conditions and cultural norms.

While locally adapted approaches create opportunities for diverse talent pools, they limit a company’s ability to build on its global learning in hiring, assessing, developing and retaining top global talent. This requires more integration across business units. One company in our study didn’t coordinate hiring and development efforts across its different divisions, so even though it had diverse talent pools, it wasn’t able to take advantage of cross-learning opportunities. Shell, on the other hand, has come to embrace HR policy replication across divisions over innovation. Companies that find a balance between global standardization and integration and local implementation have the best of both worlds. They can align their talent management practices with both local and global needs, resulting in a deep, diverse talent pool.

Principle 6: Employer Branding Through Differentiation

Attracting talent means marketing the corporation to people who will fulfill its talent requirements. In order to attract employees with the right skills and attitudes, companies need to find ways to differentiate themselves from their competitors. 21 P&G, for example, was in one year able to attract about 600,000 applicants worldwide — of whom it hired about 2,700 — by emphasizing opportunities for long-term careers and promotion from within.

The companies in our study differed considerably in how they resolve the tension between maintaining a consistent brand identity across business units and regions and responding to local demands. Shell, for example, uses one global brand for HR excellence and several global practices or processes for all its businesses. The brand highlights talent as Shell’s top priority; each business is then able to take that global brand and apply it locally. This means that rather than having all branding efforts coming from corporate headquarters, each subsidiary receives its own resources to build the brand in accordance with the local market demands and the need for differentiation.

Intel takes a different approach. It positions many of its top-level recruiters outside the United States to ensure that the Intel brand is promoted worldwide. For instance, Intel has recently set up a large production facility in Vietnam. To staff the operation, the company sent a top-level HR manager from its California corporate office to build local awareness of Intel as an employer. “Hiring top talent, no matter where we are, is top priority for Intel,” the manager explained. To accomplish this, Intel has become involved with local governments and universities to advance education and computer literacy. Such investments may not pay off immediately, but they put roots in the ground in countries that see hundreds of foreign companies come and go each year.

Infosys has also taken significant steps to increase its name recognition, improve its brand attraction and fill its talent pipeline by combining global branding activities with efforts in local communities. For example, the company initiated a “Catch Them Young” program in India that trains students for a month; the students are then invited to work for Infosys on a two-month project. In rural areas, Infosys offers computer awareness programs in local languages to help schoolchildren become more comfortable with high-tech equipment. Although not initially directed at recruitment and branding, the program has been an effective strategy for enlarging the pool of IT-literate and Infosys-devoted students in India, which may eventually make it easier to find talented software engineers. Infosys’s global internship program, called InStep, however, is central to the company’s employee branding effort: It invites students from top universities around the world to spend three months at the Infosys Bangalore campus. It is part of an ongoing effort to make the company more attractive to potential candidates outside of India and to tap into the worldwide talent pool.

One way companies are trying to get an edge on competitors in attracting talent is by stressing their corporate social responsibility activities. GlaxoSmithKline, the pharmaceutical giant, offers an excellent case in point. The company capitalizes on its employment brand and reputation through regular news releases and media events at key recruitment locations. Former CEO Jean-Pierre Garnier stressed the importance of GSK’s philanthropic activities in increasing the attractiveness of the company among potential recruits and providing an inspiring mission to the employees:

GSK is big in philanthropic undertakings; we spend a lot of money with a very specific goal in mind, such as eradicating a disease. … [O]ur scientists, who are often very idealistic, follow this like an adventure. It can make the difference when they have to choose companies — they might pick us because of the effort we make to provide drugs to the greatest number of people regardless of their economic status. 22

While some of the leading companies in our study see corporate social responsibility as an integral part of their talent management and branding activities, others consider improved brand attraction as a welcome result of their philanthropic activities.

A Convergence of Practices

In addition to adhering to a common set of talent management principles, leading companies follow many of the same talent-related practices. Although our survey showed that global corporations continue to use overall HR management systems that align with their cultures and strategic objectives, the companies are becoming more similar — and also more sophisticated — in how they manage talent. Several factors seem to be driving the convergence. First, companies compete for the same talent pool, especially graduates of international business schools and top universities. Second, the trend toward greater global integration 23 means that companies want to standardize their approaches to talent recruitment, development and management to ensure internal consistency. And third, the visibility and success of companies such as GE, amplified by commentary by high-profile consulting firms and business publications, have led to widespread imitation.

Yet, as we noted earlier, best practices are only “best” when they’re applied in a given context; what works for one company may not work in another. Indeed, the need for alignment — internally across practices, as well as with the strategy, culture and external environment — has profound implications for talent management. Even with the global convergence in terms of the practices used, companies cannot simply mimic top performers. They need to adapt talent management practices to their own strategy and circumstances and align them closely with their leadership philosophy and value system, while at the same time finding ways to differentiate themselves from their competitors. Multinational corporations that excel in managing talent are likely to retain a competitive edge.

About the Authors

Günter K. Stahl is a professor of international management at WU Vienna and adjunct professor of organizational behavior at INSEAD. Ingmar Björkman is a professor at Aalto University School of Economics and Hanken School of Economics in Finland. Elaine Farndale is an assistant professor of labor studies and employment relations at Pennsylvania State University and an assistant professor at Tilburg University in the Netherlands. Shad S. Morris is an assistant professor of management and human resources at the Fisher College of Business at Ohio State University. Jaap Paauwe is a professor of human resources at Tilburg University and Erasmus University Rotterdam in the Netherlands. Philip Stiles is a senior lecturer at Judge Business School at the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom. Jonathan Trevor is a lecturer in human resources and organizations at the University of Cambridge. Patrick Wright is the William J. Conaty GE Professor of Strategic HR at Cornell University.

1. See R.E. Lewis and R.J. Heckman, “Talent Management: A Critical Review,” Human Resource Management Review 16 (2006): 139-154.

2. E.G. Chambers, M. Foulon, H. Handfield-Jones, S.M. Hankin and E.G. Michaels, “The War for Talent,” McKinsey Quarterly 3 (1998): 44-57.

3. E.E. Lawler III, “The Folly of Forced Ranking,” Strategy & Business 28 (2002): 28-32; and J. Pfeffer and R.I. Sutton, “Hard Facts, Dangerous Half-Truths and Total Nonsense: Profiting from Evidence-Based Management” (Boston: Harvard Business Press, 2006).

4. Chambers, “The War for Talent.”

5. M.A. Huselid, R.W. Beatty and B. Becker, “The Differentiated Workforce” (Boston: Harvard Business Press, 2009).

6. R.S. Schuler, S.E. Jackson and I. Tarique, “International HRM: A North America Perspective, a Thematic Update and Suggestions for Future Research,” International Journal of Human Resource Management (May 2007): 15-43.

7. C.A. Bartlett and A.N. McLean, “GE’s Talent Machine: The Making of a CEO,” Harvard Business School Case no. 9-304-049 (Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing, 2006).

8. P. Wright and M. Stewart, “From Bunker to Building: Results of the 2010 Cornell/CAHRS Chief Human Resource Officer Survey,” www.ilr.cornell.edu/cahrs.

9. J.A. Chatman and S.E. Cha, “Leading by Leveraging Culture,” California Management Review 45 (2003): 20-34.

10. J. Pfeffer and J.F. Veiga, “Putting People First for Organizational Success,” Academy of Management Executive 13 (1999): 37-49.

11. S. Palmisano, “Leading Change When Business Is Good,” Harvard Business Review (December 2004): 60-70.

12. T.J. Erickson, “Gen Y in the Workforce,” Harvard Business Review (February 2009): 43-49.

13. G.K. Stahl and I. Björkman, “Winning the War for Talent: Accenture’s Great Place to Work for Women Strategy,” unpublished INSEAD case study.

14. W.J. Holstein, “Best Companies for Leaders: P&G’s A.G. Lafley Is No. 1 for 2005,” Chief Executive (November 2005): 16-20.

15. Wright, “From Bunker to Building.”

16. E. Farndale, H. Scullion and P. Sparrow, “The Role of the Corporate HR Function in Global Talent Management,” Journal of World Business 45, no. 2 (2010): 161-168.

17. M. Guthridge, A.B. Komm and E. Lawson, “The People Problem in Talent Management,” McKinsey Quarterly 2 (2006): 6-8.

18. P.M. Rosenzweig and N. Nohria, “Influences on Human Resource Management Practices in Multinational Corporations,” Journal of International Business Studies 25 (1994): 229-251.

19. C. Bartlett and S. Ghoshal, “Managing Across Borders: The Transnational Solution” (London: Hutchinson Business Books, 1989).

20. P. Evans, V. Pucik and I. Björkman, “The Global Challenge: International Human Resource Management,” 2nd ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2011).

21. Evans,“The Global Challenge.”

22. F. Brown, “Head-to-Head: Interview with Jean-Pierre Garnier,” World Business (September 2006): 20-23.

23. S. Palmisano, “The Globally Integrated Enterprise,” Foreign Affairs 85, no. 3 (May-June 2006): 127-136.

More Like This

Add a comment cancel reply.

You must sign in to post a comment. First time here? Sign up for a free account : Comment on articles and get access to many more articles.

Comments (6)

Six principles of effective global talent manag..., talent management magazine |, abigail scott, nikki.newman.

- Harvard Business School →

- Faculty & Research →

- February 2008 (Revised November 2008)

- HBS Case Collection

Global Talent Management at Novartis

- Format: Print

- | Pages: 17

Related Work

- Faculty Research

Global Talent Management at Novartis (TN)

- Global Talent Management at Novartis (TN) By: Jordan I. Siegel

Valuing your talent: Case studies

Find out how other businesses are using people measures to improve their organisations through these case studies

In this series

The Head of Leadership Development at the world’s largest steel company, Brian Callaghan, describes how people measures and performance management systems are helping ArcelorMittal build their talent base.

The retailer’s people are at the heart of the organisation’s success and growth. Find out how the company’s HR strategy and operations are specifically tailored to reflect the individual needs of their employees

Employing over 180,000 people across 40 countries, Capgemini relies on the expertise and skills of its workforce to deliver high organisational and financial performance. Faced with challenges such as siloed departments and reporting of often disconnected data, Capgemini sought to create a tool that would offer access to key human capital data and insights in one place.

This case study provides insight into Coca-Cola Enterprises’ (CCE) data analytics journey. Given the complexity of the CCE operation, its global footprint and various business units, a team was needed to provide a centralised HR reporting and analytics service to the business. This led to the formation of a HR analytics team serving 8 countries. Read the full case study to find out how the HR analytics team were able to increase data maturity and improve business performance.

Enterprise Rent-A-Car places a lot of importance on the gathering and interpreting of workforce data. We interviewed Leigh Lafever-Ayer, HR Director UK & Ireland at Enterprise Rent-A-Car to find out more about the data they collect, and how they use it.

Halfords, a specialist retailer of leisure and car products, provides a useful current case study of effective human capital management reporting in action and demonstrates the importance between the successful alignment of business and HR strategy underpinned by clear HCM measures.

London Councils is a lobbying organisation working across political parties to promote the interests of London’s 32 borough councils and deliver services on behalf of the public. One of the ways London Councils provides support is through a professional HR Metrics and Workforce Planning network which helps London boroughs report on, explore and share people data to improve performance.

Microsoft is a data-driven organisation that puts data-led decision making at the heart of its business strategy. Targeted gathering of their human capital data is enabling them to gain analytical insights and solve practical business problems across their organisation.

This case study explores the application of recognition technology within a complex organisational environment, and offers insights from senior HR leadership as to how to best implement technology to drive up engagement

Unilever’s Senior Vice President of Leadership and Organisational Development, Leena Nair, describes their HR vision – People, Place, Performance – and how people measures are helping to secure the top talent, make Unilever the best place to work, and ensure their people are performing to their productive best.

CFO, Xavier Heiss, explains how the two business functions have worked together to increase the value of the services they provide through understanding the intangible value people bring to their customers, such as goodwill.

Tackling barriers to work today whilst creating inclusive workplaces of tomorrow.

Bullying and harassment

Discover our practice guidance and recommendations to tackle bullying and harassment in the workplace.

Learn how to measure turnover and retention, and understand why people leave organisations

Creating a holistic offering to help improve workforce wellbeing

14 Nov, 2023

6 Nov, 2023

More case studies

A case study of an HR function shifting from an Ulrich+ model towards an employee experience-driven model

A case study of a people function shifting to a four-pillar model to deliver a more consistent employee experience throughout the organisation

A case study on moving to a lean, strategic HR model that operates more efficiently to support business objectives

A case study on developing strategic partners, aligning teams, increasing data analytics skill, and transitioning the L&D team into an internal academy

- Find My Rep

You are here

Global Talent Management An Integrated Approach

- Sonal Minocha - Nexford University, Washington DC

- Dean Hristov - Bournemouth University, UK

- Description

This textbook provides the theory and practice context of Global Talent Management within an accessible conceptual framework for students, spanning individuals (micro), organisations (meso) and policy (macro).

Including discussions on the development of self as global talent and current organisational approaches to the attraction, development and retention of global talent, this book encourages critical reflection of how global talent management is affected by policy, society and the economy. The authors draw on interdisciplinary fields, practical insights from global employers and wide-ranging case studies to help students grasp the complexities of this evolving field.

For many major organisations, Global Talent Management (GTM) is still a set of buzzwords, like Artificial Intelligence and Industry 4.0. Organisations know that they are increasingly being forced to attract and retain talent in a globalised labour market, but their human resources policies and practices remain firmly rooted in a national mind set. Recruitment and selection procedures implicitly assume that applicants are home-based, requiring “post codes” and “equality monitoring data” that make no sense to international candidates. HR departments struggle to organise interviews for remote candidates in different time zones. Most damning, “onboarding” procedures routinely fail to recognise the challenges facing new employees who have moved across national borders and cultural and linguistic boundaries to take up their jobs.

This important new book brings GTM alive for a new generation of students and HR professionals, who will be building their careers in the new globalised world, rather than the set of nationally segmented labour markets that characterised their parents’ experience. By drawing on perspectives from theory, practice and policy, Minocha and Hristov present GTM as a holistic approach to the recruitment, development and retention of talent in a borderless world. This book represents the first serious attempt to mark out GTM as a distinct branch of management, rather than a sub-division of HR management.

This book is a highly accessible read that will appeal to both students and practitioners of business and management. The nature of work and talent in organisations is continually changing in our globally-connected and technology-based world. Sonal Minocha and Dean Hristov are both highly respected academics whose ideas are pushing the boundaries of our understanding of talent development. In this book, they have developed a number of global talent management constructs based on case evidence research that offer a valuable talent management toolkit.

Preview this book

For instructors.

Please select a format:

Select a Purchasing Option

- Electronic Order Options VitalSource Amazon Kindle Google Play eBooks.com Kobo

Related Products

Case Study: Infosys – Talent Management Processes Automation with AI

- First Online: 17 June 2023

- pp 1451–1458

Cite this chapter

- Parasuram Balasubramanian 3 &

- D. R. Balakrishna 4

Part of the book series: Springer Handbooks ((SHB))

4948 Accesses

The IT industry has been a pioneer in the use of Automation and AI. Infosys, a global leader in next-generation digital services and consulting, has expanded the use of automation across their internal processes and offers these capabilities to their clients. One of their outstanding success stories has been in recruitment.

As a large-scale recruiter, the recruitment function at Infosys was complex, voluminous, and highly manual. From over 130,000 employees in 2010, the firm had nearly 260,000 employees in 2020. They were processing over 2,140,000 in 2020 that was 2.5 times the applications received in 2010. This created a tremendous workload for the recruitment team.

The automation journey of the Recruitment function at Infosys has been arduous. During their solution building, they were hit by new challenges arising out of a global pandemic in early 2020, when they had to suddenly move to a virtual environment. The disaster also created the need to expand their workforce as the number of IT projects grew.

The automation program was executed at speed to respond in time to the continuously changing landscape. It resulted in transformational changes, bringing both high efficiency and effectiveness. For example, the time taken from sourcing to making an offer is reduced by 86%. The project demonstrates the structured approach to discovering, developing, and democratizing AI and automation, thereby encouraging its adoption. Infosys continues to invest in the technology as they believe it plays a critical role in staying relevant to their clients by delivering industry-leading business solutions.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Shaping AI Transformation: Digital Competencies and Augmentation Strategies of HRD Professionals

The (Post)Pandemic Employment Model

The critical role of HRM in AI-driven digital transformation: a paradigm shift to enable firms to move from AI implementation to human-centric adoption

Acknowledgments.

We would like to thank Ashok K Panda, Anie Mathew, and Meghna Chatterjee from Infosys for their contribution in collating and curating this case study. See Chapter 46 for broader content of automation in data science, software, and information services.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Theme Work Analytics Pvt. Ltd., Bangalore, India

Parasuram Balasubramanian

Infosys Ltd., Bengaluru, India

D. R. Balakrishna

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

PRISM Center and School of Industrial Engineering, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, USA

Shimon Y. Nof

Appendix 1: A Detailed Look at Major Activities and Their Intricacies

1.1 sourcing: raising hiring requests and finding resumes.

Hiring Requisitions, which were earlier created manually, are now automatically created by directly fetching data from talent indent tools. Job descriptions of common roles are predefined and auto-populated with recruiters having the option to manually intervene. Once a new job is posted, various sourcing channels are automatically updated.

Sourcing Applications: Earlier recruiters had to wait for candidates to apply or search and download best-fit resumes from different channels to create candidate profiles in internal system. With InTAP, resumes are uploaded in bulk, which are then automatically parsed for profile creation.

The integrated talent platform sends recruiters a list of AI-enabled recommendations of candidates picked from internal databases as well as external job boards. They are ranked in the order of their fitment to the job/skill with 95% accuracy. These candidates are matched for their skill, experience, location, proficiency, accreditation, and other criteria. The best candidates can then be tagged by the recruiter for the job. This cuts down nearly 80–90% of the sourcing time.

Candidate experience is also enhanced as most of the fields in application form are prepopulated.

1.2 Screening: Prescreening, Shortlisting, and Prescheduling

Prescreening: Weeding out duplicate applications, applicants from blacklisted companies, or alumni who do not qualify to be rehired was earlier done manually using excel comparisons. Removing exact duplicates is now fully automated based on AI logic with auto-rejections. Blacklisted candidates are auto-flagged based on organization policy. For rehires, system pulls past employment details from internal applications such as the separation tool and makes recommendations.

Screening: The resume parser throws up a list of recommendations and ranks them based on the match between candidate’s profile and job requirement. The ranking logic is driven by explainable AI, and an 80% match indicates high probability of the candidate being a good fit for the role. The parser has eliminated recruited team’s task of sifting manually through thousands of resumes.