- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Sweepstakes

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

7 Depression Research Paper Topic Ideas

In psychology classes, it's common for students to write a depression research paper. Researching depression may be beneficial if you have a personal interest in this topic and want to learn more, or if you're simply passionate about this mental health issue. However, since depression is a very complex subject, it offers many possible topics to focus on, which may leave you wondering where to begin.

If this is how you feel, here are a few research titles about depression to help inspire your topic choice. You can use these suggestions as actual research titles about depression, or you can use them to lead you to other more in-depth topics that you can look into further for your depression research paper.

What Is Depression?

Everyone experiences times when they feel a little bit blue or sad. This is a normal part of being human. Depression, however, is a medical condition that is quite different from everyday moodiness.

Your depression research paper may explore the basics, or it might delve deeper into the definition of clinical depression or the difference between clinical depression and sadness .

What Research Says About the Psychology of Depression

Studies suggest that there are biological, psychological, and social aspects to depression, giving you many different areas to consider for your research title about depression.

Types of Depression

There are several different types of depression that are dependent on how an individual's depression symptoms manifest themselves. Depression symptoms may vary in severity or in what is causing them. For instance, major depressive disorder (MDD) may have no identifiable cause, while postpartum depression is typically linked to pregnancy and childbirth.

Depressive symptoms may also be part of an illness called bipolar disorder. This includes fluctuations between depressive episodes and a state of extreme elation called mania. Bipolar disorder is a topic that offers many research opportunities, from its definition and its causes to associated risks, symptoms, and treatment.

Causes of Depression

The possible causes of depression are many and not yet well understood. However, it most likely results from an interplay of genetic vulnerability and environmental factors. Your depression research paper could explore one or more of these causes and reference the latest research on the topic.

For instance, how does an imbalance in brain chemistry or poor nutrition relate to depression? Is there a relationship between the stressful, busier lives of today's society and the rise of depression? How can grief or a major medical condition lead to overwhelming sadness and depression?

Who Is at Risk for Depression?

This is a good research question about depression as certain risk factors may make a person more prone to developing this mental health condition, such as a family history of depression, adverse childhood experiences, stress , illness, and gender . This is not a complete list of all risk factors, however, it's a good place to start.

The growing rate of depression in children, teenagers, and young adults is an interesting subtopic you can focus on as well. Whether you dive into the reasons behind the increase in rates of depression or discuss the treatment options that are safe for young people, there is a lot of research available in this area and many unanswered questions to consider.

Depression Signs and Symptoms

The signs of depression are those outward manifestations of the illness that a doctor can observe when they examine a patient. For example, a lack of emotional responsiveness is a visible sign. On the other hand, symptoms are subjective things about the illness that only the patient can observe, such as feelings of guilt or sadness.

An illness such as depression is often invisible to the outside observer. That is why it is very important for patients to make an accurate accounting of all of their symptoms so their doctor can diagnose them properly. In your depression research paper, you may explore these "invisible" symptoms of depression in adults or explore how depression symptoms can be different in children .

How Is Depression Diagnosed?

This is another good depression research topic because, in some ways, the diagnosis of depression is more of an art than a science. Doctors must generally rely upon the patient's set of symptoms and what they can observe about them during their examination to make a diagnosis.

While there are certain laboratory tests that can be performed to rule out other medical illnesses as a cause of depression, there is not yet a definitive test for depression itself.

If you'd like to pursue this topic, you may want to start with the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). The fifth edition, known as DSM-5, offers a very detailed explanation that guides doctors to a diagnosis. You can also compare the current model of diagnosing depression to historical methods of diagnosis—how have these updates improved the way depression is treated?

Treatment Options for Depression

The first choice for depression treatment is generally an antidepressant medication. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are the most popular choice because they can be quite effective and tend to have fewer side effects than other types of antidepressants.

Psychotherapy, or talk therapy, is another effective and common choice. It is especially efficacious when combined with antidepressant therapy. Certain other treatments, such as electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) or vagus nerve stimulation (VNS), are most commonly used for patients who do not respond to more common forms of treatment.

Focusing on one of these treatments is an option for your depression research paper. Comparing and contrasting several different types of treatment can also make a good research title about depression.

A Word From Verywell

The topic of depression really can take you down many different roads. When making your final decision on which to pursue in your depression research paper, it's often helpful to start by listing a few areas that pique your interest.

From there, consider doing a little preliminary research. You may come across something that grabs your attention like a new study, a controversial topic you didn't know about, or something that hits a personal note. This will help you narrow your focus, giving you your final research title about depression.

Remes O, Mendes JF, Templeton P. Biological, psychological, and social determinants of depression: A review of recent literature . Brain Sci . 2021;11(12):1633. doi:10.3390/brainsci11121633

National Institute of Mental Health. Depression .

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition . American Psychiatric Association.

National Institute of Mental Health. Mental health medications .

Ferri, F. F. (2019). Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2020 E-Book: 5 Books in 1 . Netherlands: Elsevier Health Sciences.

By Nancy Schimelpfening Nancy Schimelpfening, MS is the administrator for the non-profit depression support group Depression Sanctuary. Nancy has a lifetime of experience with depression, experiencing firsthand how devastating this illness can be.

- Breast Cancer Paper Topics Topics: 145

- Myocardial Infarction Research Topics Topics: 52

- Communicable Disease Research Topics Topics: 58

- Hepatitis Essay Topics Topics: 57

- Arthritis Paper Topics Topics: 58

- Heart Attack Topics Topics: 54

- Dorothea Orem’s Theory Research Topics Topics: 85

- Asthma Topics Topics: 155

- Sleep Deprivation Topics Topics: 48

- Chlamydia Research Topics Topics: 52

- Melanoma Essay Topics Topics: 60

- Hypertension Essay Topics Topics: 155

- Patient Safety Topics Topics: 148

- Nursing Theory Research Topics Topics: 207

- Heart Failure Essay Topics Topics: 83

233 Depression Research Topics & Essay Titles + Examples

If you’re looking for a good depression research title, you’re at the right place! StudyCorgi has prepared a list of titles for depression essays and research questions that you can use for your presentation, persuasive paper, and other writing assignments. Read on to find your perfect research title about depression!

🙁 TOP 7 Depression Title Ideas

🏆 best research topics on depression, ❓ depression research questions, 👍 depression research topics & essay examples, 📝 argumentative essay topics about depression, 🌶️ hot depression titles for a paper, 🔎 creative research topics about depression, 🎓 most interesting depression essay topics, 💡 good titles for depression essays.

- Teenage Depression: Causes and Symptoms

- Depression: Case Conceptualization and Treatment Planning

- Depression and Solutions in Psychiatry

- Adolescent Mental Health: Depression

- Depression and Depressive Disorders

- Depression: Psychoeducational Intervention

- Depression: Comprehensive Treatment Plan

- Mitigating Postnatal Depression in New Mothers: A Recreational Program Plan Post-natal depression is a popular form of depression in women. This paper presents an activity plan for the use of leisure as a therapeutic response to post-natal depression.

- Depression in Hispanic Culture There are different ways in which culture or ethnicity can impact the treatment of the development of mental health disorders.

- Depression as It Relates to Obesity This paper will argue that there is a positive correlation between depression and obesity. The paper will make use of authoritative sources to reinforce this assertion.

- Mental Health Association of Depression and Alzheimer’s in the Elderly Depression can be a part of Alzheimer’s disease. Elderly people may have episodes of depression, but these episodes cannot be always linked to Alzheimer’s disease.

- Social Media as a Cause of Anxiety and Depression Anxiety and depression are considerable problems for world society. Numerous studies have linked high social media use with high levels of anxiety and depression.

- The Concept of Postpartum Depression Postpartum depression is a common condition involving psychological, emotional, social, and physical changes that many new mothers experience immediately after giving birth.

- Major Depression’ Symptoms and Treatment – Psychology A continuous sense of tiredness, unhappiness, and hopelessness are key signs of clinical or major depression. Such mood changes alter the daily life programs of an individual for sometimes.

- African American Children Suffering From Anxiety and Depression Depression and anxiety are common among African American children and adolescents, and they face significant barriers to receiving care and treatment.

- CBT and Depression The paper discusses the short-term and long-term application of cognitive behavioral therapy for the purpose of relapse prevention in patients with major depressive disorder.

- The Rise of Depression in the Era of the Internet Understanding how the Internet affects human lives is essential in ascertaining the reasons for the growing loneliness in the intrinsically connected world.

- Geriatric Depression Scale, Clock Drawing Test and Mini-Mental Status Examination Depression is a common condition among geriatric patients. Around 5 million older adults in the US experience significant morbidity from depression.

- History and Treatment of Depression Depression is currently one of the most common medical conditions among the adult population in the US. The paper aims to investigate the history and treatment of depression.

- Self-Esteem and Depression in Quantitative Research The topic that has been proposed for quantitative research pertains to the problem of the relationship between self-esteem and depression.

- Impact of Depression on a Family The article makes a very powerful argument about the effects of depression on the relatives of the patient by identifying the major factors that put the family into a challenging position.

- The Causes of Depression and How to Overcome It In this self-reflection essay, the author describes the causes of his depression and the steps he is taking to overcome it.

- Application of Analysis of Variance in the Analysis of HIV/AIDS-Related Depression Cases Analysis of variance (ANOVA) is a commonly used approach in the testing of the equality of various means using variance.

- Diagnosing and Managing Headaches and Weight Gain in a 21-Year-Old Young people are busy at studies or at work and do not pay much attention to primary symptoms unless they influence the quality of life.

- Depression in Older Adults Depression is one of the most common mental illnesses in the world. Evidence-based holistic intervention would provide more effective treatment for elderly patients with depression.

- Guideline on Antidepressants’ Use During Depression The paper states that in cases when antidepressants are necessary, it is vital to follow the algorithm and ensure the most effective drug is selected.

- Postnatal Depression: Prevention and Treatment This presentation will cover the reflection on the health promotion aimed at postnatal depression prevention and treatment in Mental Health UK.

- Treating Psychological Disorders: Depression The best psychological treatment for clinical depression is Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and Psychodynamic Approach, which focus on altering negative thoughts.

- Social Media as a Tool for Depression Detection This article would make a source for research on the link between social media and depression because it suggests an adequate technological tool for detecting depressive signs.

- Anxiety, Depression, and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Currently, many people experience anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder that affect their general health.

- Women’s Mental Health Disorder: Major Depression The mental health disorder paper aims to explore major depression, its symptoms, assessment, and intervention strategies appropriate for women.

- Depression in Young Adults: Annotated Bibliography The purpose of this study was to discover sociodemographic and health traits related to depression sufferers’ usage of various mental health services.

- Depression in Middle-Aged African Women The research study investigates depression in middle-aged African women because the mental health of the population is a serious concern of the modern healthcare sector.

- Detecting Depression in Young Adults: Literature Review The paper shows a need for early identification of depression symptoms in primary care practice. PHQ-2 and PHQ-9 are useful tools for portraying symptoms.

- Predicting Barriers to Treatment for Depression Mental health issues such as depression and drug abuse are the most frequent among teenagers and young adults. In this age range, both disorders tend to co-occur.

- What Are the Characteristics and Causes of Depression?

- Why Are Athletes Vulnerable to Depression?

- Why and How Adolescents Are Affected by Generalized Anxiety Disorder and Clinical Depression?

- Does Depression Assist Eating Disorders?

- What Should You Know About Depression?

- How Can Mother Nature Lower Depression and Anxiety?

- How Can Video Games Relieve Stress and Reduce Depression?

- When Does Teacher Support Reduce Depression in Students?

- Why Are Teenagers Affected by Depression?

- How Teens and Depression Today?

- Are Mental Health Issues Like Depression Related to Race?

- What Does Depression Mean?

- How Did the Depression Affect France?

- How Does Depression Stop?

- When Postpartum Depression Leads to Psychosis?

- How Do Medication and Therapy Combat Depression?

- What Are the Leading Causes of Depression?

- What About Drugs for Anxiety and Depression?

- What’s the Big Deal About Anxiety and Depression in Students?

- How Should Childhood Depression and Anxiety Be?

- How Do Gender Stereotypes Warp Our View of Depression?

- What Are the Signs of Teenage Depression?

- Are Testosterone Levels and Depression Risk Linked Based on Partnering and Parenting?

- How Psychology Helps People With Depression?

- How Should Childhood Depression and Anxiety Be Treated or Dealt With?

- Early Diagnosis of Depression: Public Health Depression in young adults has become a significant health problem across the US. It causes persistent feelings of loss of interest in activities and sadness.

- Depression and Social Media in Scientific vs. Popular Articles The damage can come in the form of misinformation, which can result in an unjustified and unnecessary self-restriction of social media.

- Depression in Adolescence: Causes and Treatment Depression amongst young adults at the puberty stage comes in hand with several causes that one cannot imagine, and depression happens or is triggered by various reasons.

- Addressing Depression Among Native Youths The current paper aims to utilize a Medicine Wheel model and a social work paradigm to manage depression among Native American Indian youths.

- Psychological Assessments and Intervention Strategies for Depression The article presents two case studies highlighting the importance of psychological assessments and intervention strategies for individuals experiencing depression.

- The Impact of Postpartum Maternal Depression on Postnatal Attachment This paper examines the influence of postpartum maternal depression on postnatal infant attachment, discusses the adverse effects of depression on attachment.

- Marijuana Effects on Risk of Anxiety and Depression The current paper aims to find out whether medical cannabis can positively affect anxiety and depression and the process of their treatment.

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Anxiety and Depression Cognitive behavioral therapy analyzes the unconscious processes influencing the normal functioning of the human body, causing different pathologies.

- Hypnotherapy as an Effective Method for Treating Depression This paper explores the use of hypnotherapy as a treatment for depression and highlights the advantages of hypnosis in addressing depressive symptoms.

- Depression and Anxiety: Mary’s Case Mary’s husband’s death precipitated her depression and anxiety diagnosis. She feels lonely and miserable as she struggles with her daily endeavors with limited emotional support.

- Postpartum Depression in Women and Men The focus of the paper is health problems that affect women after giving birth to a child, such as depression. The author proposes that men also experience postpartum depression.

- Repression and Depression in “The Yellow Wallpaper” by Charlotte Perkins Gilman In “The Yellow Wallpaper” by Charlotte Perkins Gilman, the author highlighted the connection between repression and depression.

- Men and Depression: Signs, Symptoms, Causes, and Treatment Depression in men and women has several incompatibilities as males suffer from health problems more often than women as they rarely express their emotions.

- Promotion of Change Regarding Adolescent Depression In the essay, the author describes the methods to evaluate the symptoms of a patient who has been referred for counseling with depression.

- Interventions to Cope With Depression Depression is characterized by sadness, anxiety, feelings of worthlessness, and helplessness. These feelings do not necessarily relate to life events.

- Bipolar Depression and Bipolar Mania Although all bipolar disorders are characterized by periods of extreme mood, the main difference between them is the severity of the condition itself.

- Post-Stroke Anxiety and Depression The purpose of the given study is to ascertain how cognitive behavior therapy affects individuals with post-stroke ischemia in terms of depression reduction.

- Depression and Anxiety Management The medical staff will investigate the treatment modalities currently being utilized for the large population of patients experiencing symptoms of anxiety and depression.

- Impacts of Stress of Low Income on the Risk of Depression in Children Socioeconomic hardships lead to a decline in the quality of parenting and the development of psychological and behavioral problems in children.

- Depression: Diagnostics and Treatment Depression, when it remains unchecked, can cause detrimental effects to individuals, such as suicide, which will eventually equate to mental disorders.

- Depression and Anxiety in Mental Health Nurses Depression and anxiety are the most common mental diseases in humans. Nurses who work in mental health are at significant risk of getting psychiatric illnesses.

- Psychedelics in Depression and Anxiety Treatment Mental illnesses have become an essential part of health in the last few decades, with sufficient attention being devoted to interventions that resolve them.

- Depression and Anxiety Among African-American Children Depression and anxiety are common among African-American children and adolescents, but they face significant barriers to receiving care and treatment due to their age and race.

- Why Are Physical Activities Treatments for Depression? In this paper, the connection between physical activities and depression will be analyzed, and the common counterargument will be discussed.

- Depression in the Older Population The paper discusses depression is an actual clinical disorder for older people with specific reasons related to their age.

- Nutrition and Depression: A Psychological Perspective When discussing nutrition in toddlers and certain behavioral patterns, one of the first standpoints to pay attention to is the humanistic perspective.

- Social Media and Depression in Adolescents: The Causative Link This paper explores how social media causes depression in adolescents during the social-emotional stage of life.

- “Yoga for Depression” Article by The Minded Institute One can say that depression is both the biological and mental Black Death of modern humanity in terms of prevalence and negative impact on global health.

- Therapeutic Interventions for the Older Adult With Depression and Dementia The paper researches the therapeutic interventions which relevant for the older people with depression and dementia nowadays.

- Depression Among Patients With Psoriasis Considering psoriasis as the cause of the development of depressive disorders, many researchers assign a decisive role to the severe skin itching that accompanies psoriasis.

- Qi Gong Practices’ Effects on Depression Qi Gong is a set of physical and spiritual practices aimed at the balance of mind, body, and soul and the article demonstrates whether it is good or not at treating depression.

- The Effects of Forgiveness Therapy on Depression for Women The study analyzes the impact of forgiveness therapy on the emotional state of women who have experienced emotional abuse.

- Relation Between the COVID-19 Pandemic and Depression The paper is to share an insight into the detrimental effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of thousands of people and provide advice on how to reduce its impact.

- Post-operative Breast Cancer Patients With Depression: Annotated Bibliography This paper is an annotated bibliography about risk reduction strategies at the point of care: Post-operative breast cancer patients who are experiencing depression.

- How Covid-19 Isolation Contributed to Depression and Adolescent Suicide The pandemic affected adolescents because of stringent isolation measures, which resulted in mental challenges such as depression and anxiety, hence suicidal thoughts.

- Is depression a biological condition or a result of unrealistic expectations?

- Should employers be legally required to provide support to workers with depression?

- Do the media portrayals of depression accurately reflect people’s experiences?

- Social media contributes to depression rates by eliciting the feeling of loneliness.

- Should mental health screening be mandatory in schools?

- Should depression be reclassified as a neurological disorder?

- Antidepressants are an overused quick-fix solution to depression.

- Should non-pharmacological treatments for depression be prioritized?

- Should depression be considered a disability?

- The use of electroconvulsive therapy for depression should be banned.

- Depression and Anxiety in Older Generation Depression and anxiety represent severe mental disorders that require immediate and prolonged treatment for patients of different ages.

- Coping with Depression After Loss of Loved Ones This case is about a 60-year-old man of African American origin. He suffered from depression after his wife’s death, which made him feel lonely and isolated.

- Postpartum Depression Screening Program Evaluation In order to manage the depression of mothers who have just delivered, it is important to introduce a routine postpartum depression-screening program in all public hospitals.

- Depression: Symptoms, Causes and Treatment Depression interferes with daily routine, wasting valuable time and lowering production. Persistent downs or blues, sadness, and anger may be signs of depression.

- Is Creativity A Modern Panacea From Boredom and Depression? Communication, daily life, and working patterns become nothing but fixed mechanisms that are deprived of any additional thoughts and perspectives.

- Adolescent Males With Depression: Poly-Substance Abuse Depression is the most crucial aspect that makes young males indulge in poly-substance abuse. There are various ways in which male adolescents express their depression.

- The Health of the Elderly: Depression and Severe Emotional Disturbance This study is intended for males and females over the age of 50 years who are likely to suffer from depression and severe emotional disturbance.

- Suicidal Ideation & Depression in Elderly Living in Nursing Home vs. With Family This paper attempts to compare the incidence of suicidal ideation and depression among elderly individuals living in nursing homes and those living with family in the community.

- Major Depression: Symptoms and Treatment Major depression is known as clinical depression, which is characterized by several symptoms. There are biological, psychological, social, and evolutionary causes of depression.

- Health Disparity Advocacy: Clinical Depression in the U.S. Recent statistics show that approximately more than 10 million people suffer from severe depression each year in the U.S..

- The Treatment of Anxiety and Depression The meta-analysis provides ample evidence, which indicates that CES is not only effective but also safe in the treatment of anxiety and depression.

- Depression Intervention Among Diabetes Patients The research examines the communication patterns used by depression care specialist nurses when communicating with patients suffering from diabetes.

- Postnatal Depression in New Mothers and Its Prevention Leisure activities keep new mothers suffering from postnatal depression busy and enable them to interact with other members of the society.

- Literature Evaluation on the Depression Illness The evaluation considers the articles that study such medical illness as depression from different planes of its perception.

- Treatment of Major Depression The purpose of the paper is to identify the etiology and the treatment of major depression from a psychoanalytic and cognitive perspective.

- Edinburgh Depression Screen for Treating Depression Edinburgh Depression screen is also known as Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale which is used to screen pregnant and postnatal women for emotional distress.

- Depression Treatment Variants in the US There is a debate regarding the best formula for depression treatment whereby some argue for using drugs, whereas others are advocating for therapy.

- Effects of Music Therapy on Depressed Elderly People Music therapy has been shown to have positive effects among people, and thus the aim was to assess the validity of such claims using elderly people.

- Depression in the Elderly: Treatment Options Professionals may recommend various treatment options, including the use of antidepressants, psychotherapy such as cognitive-behavioral therapy.

- Depression Treatments and Therapeutic Strategies This article examines the effectiveness of different depression treatments and reviews the therapeutic strategies, which can be helpful if the initial treatment fails.

- Depression and the Nervous System Depression is a broad condition that is associated with failures in many parts of the nervous system. It can be both the cause and the effect of this imbalance.

- Depression: Types, Symptoms, Etiology & Management Depression differs from other disorders, connected with mood swings, and it may present a serious threat to the individual’s health condition.

- The Effect of Music Therapy on Depression One major finding of study is that music therapy alleviates depression among the elderly. Music therapy could alleviate depression.

- “Neighborhood Racial Discrimination and the Development of Major Depression” by Russell The study investigates how neighborhood racial discrimination influences this severe mental disorder among African American Women.

- Adolescent Depression and Physical Health Depression in adolescents and young people under 24 is a factor that affects their physical health negatively and requires intervention from various stakeholders.

- Family Support to a Veteran With Depression Even the strongest soldiers become vulnerable to multiple health risks and behavioral changes, and depression is one of the problems military families face.

- Alcohol and Depression Article by Churchill and Farrell The selected article for this discussion is “Alcohol and Depression: Evidence From the 2014 Health Survey for England” by Sefa Awaworyi Churchill and Lisa Farrell.

- Does Social Media Use Contribute to Depression? Social media is a relatively new concept in a modern world. It combines technology and social tendencies to enhance interaction through Internet-based gadgets and applications.

- Negative Effects of Depression in Adolescents on Their Physical Health Mental disorders affect sleep patterns, physical activity, digestive and cardiac system. The purpose of the paper to provide information about adverse impacts of depression on health.

- Depression in the Contemporary Society Public awareness about depression has increased in recent years, with more attention dedicated to the need for addressing this serious mental health illness and less stigmatization.

- Elderly Depression: Symptoms, Consequences, Behavior, and Therapy The paper aims to identify symptoms, behavioral inclinations of older adults, consequences of depression, and treatment ways.

- Components of the Treatment of Depression The most effective ways of treating people with depression include pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy or a combination of both.

- Mood Disorders: Depression Concepts Description The essay describes the nature of depression, its causes, characteristics, consequences, and possible ways of treatment.

- Geriatric Depression Diagnostics Study Protocol The research question is: how does the implementation of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines affect the accuracy of diagnosing of depression?

- Protective Factors Against Youthful Depression Several iterations of multiple correlation, step-wise and hierarchical regression yielded inconclusive results about the antecedents of youthful depression.

- Can physical exercise alone effectively treat depression?

- Art therapy as a complementary treatment for depression.

- Is there a link between perfectionism and depression?

- The influence of sleep patterns on depression treatment outcomes.

- Can exposure to nature and green spaces decrease depression rates in cities?

- The relationship between diet and depression symptoms.

- The potential benefits of psychedelic-assisted therapy in treating depression.

- The role of outdoor experiences in alleviating depression symptoms.

- The relationship between depression and physical health in older adults.

- The role of workplace culture in preventing employee depression.

- Depression and Other Antecedents of Obesity Defeating the inertia about taking up a regular programme of sports and exercise can be a challenging goal. Hence, more advocacy campaigns focus on doing something about obesity with a more prudent diet.

- Depression and Related Psychological Issues Depression as any mental disorder can be ascribed, regarding the use of psychoanalysis, to a person`s inability to control his destructive or sexual instincts or impulses.

- Television Habituation and Adolescent Depression The paper investigates the theory that there is a link between heavy TV viewing and adolescent depression and assess the strength of association.

- Physiological Psychology. Postpartum Depression Depression is a focal public health question. In the childbearing period, it is commoner in females than in males with a 2:1 ratio.

- Adolescent Depression: Modern Issues and Resources Teenagers encounter many challenging health-related issues; mental health conditions are one of them. This paper presents the aspects of depression in adolescents.

- Depression Among Rich People Analysis Among the myriad differences between rich and poor people is the manner in which they are influenced by and respond to depression.

- Occupational Psychology: Depression Counselling The case involves a 28-year-old employee at Data Analytics Ltd. A traumatic event affected his mental health, causing depression and reduced performance.

- Psychotherapeutic Group: Treatment of Mild-To-Moderate Depression The aim of this manual is to provide direction and employ high-quality sources dedicated to mild-to-moderate depression and group therapy to justify the choices made for the group.

- Transition Phase of Depression and Its’ Challenges Providing psychoeducation to people with mild to moderate depression, strategies for recognizing and addressing conflict and reluctance are discussed in this paper

- “Depression and Ways of Coping With Stress” by Orzechowska et al. The study “Depression and Ways of Coping With Stress” by Orzechowska et al. aimed the solve an issue pertinent to nursing since depression can influence any patient.

- Action Research in Treating Depression With Physical Exercise Depression is one of the most common mental health disorders in the United States. The latest statistics showed that depression does not discriminate against age.

- Postpartum Depression: Evidence-Based Practice Postpartum or postnatal depression refers to a mood disorder that can manifest in a large variety of symptoms and can range from one person to another.

- Effectiveness of Telenursing in Reducing Readmission, Depression, and Anxiety The project is dedicated to testing the effectiveness of telenursing in reducing readmission, depression, and anxiety, as well as improving general health outcomes.

- Adult Depression Treatment in the United States This study characterizes the treatment of adult depression in the US. It is prompted by the findings of earlier studies, which discover the lack of efficient depression care.

- Nurses’ Interventions in Postnatal Depression Treatment This investigation evaluates the effect of nurses’ interventions on the level of women’s postnatal depression and their emotional state.

- Postpartum Depression: Evidence-Based Care Outcomes In this evidence-based study, the instances of potassium depression should be viewed as the key dependent variable that will have to be monitored in the course of the analysis.

- Postpartum Depression: Diagnosis and Treatment This paper aims to discuss the peculiarities of five one-hour classes on depression awareness, to implement this intervention among first-year mothers, and to evaluate its worth during the first year after giving birth.

- Homelessness and Depression Among Illiterate People There are various myths people have about homelessness and depression. For example, many people believe that only illiterate people can be homeless.

- Postpartum Depression In First-time Mothers The most common mental health problem associated with childbirth remains postpartum depression, which can affect both sexes, and negatively influences the newborn child.

- The Diagnosis and Treatment of Postpartum Depression Postpartum depression has many explanations, but the usual way of referring to this disease is linked to psychological problems.

- What Is Postpartum Depression? Causes, Symptoms, and Treatment The prevalence of postpartum depression is quite high as one in seven new American mothers develops this health issue.

- Baby Blues: What We Know About Postpartum Depression The term Postpartum Depression describes a wide variety of physical and emotional adjustments experienced by a significant number of new mothers.

- Depression in Adolescence as a Contemporary Issue Depression in adolescents is not medically different from adult depression but is caused by developmental and social challenges young people encounter.

- Predictors of Postpartum Depression The phenomenon of postpartum depression affects the quality of women’s lives, as well as their self-esteem and relationships with their child.

- Depression and Self-Esteem: Research Problem Apart from descriptively studying the relationship between depression and self-esteem, a more practical approach can be used to check how interventions for enhancing self-esteem might affect depression.

- The Relationship Between Depression and Self-Esteem The topic which is proposed to be studied is the relationship between depression and self-esteem. Self-esteem can be defined as individual’s subjective evaluation of his or her worth.

- The Impact of Depression on Motherhood This work studies the impact of depression screening on prenatal and posts natal motherhood and effects on early interventions using a literature review.

- Depression and Workplace Violence The purpose of this paper is to provide an in-depth analysis how can workplace violence and verbal aggression be reduced or dealt with by employees.

- Depression in Female Cancer Patients and Survivors Depression is often associated with fatigue and sleep disturbances that prevent females from thinking positively and focusing on the treatment and its outcomes.

- Treating Mild Depression: Psychotherapy and Pharmacotherapy The project intends to investigate the comparative effectiveness of the treatments that are currently used for mild depression.

- The Geriatric Population’s Depression This paper discusses how does the implementation of National Institute for Health and Care guidelines affect the accuracy of diagnosing of depression in the geriatric population.

- Problem of Depression: Recognition and Management Depression is a major health concern, which is relatively prevalent in the modern world. Indeed, in the US, 6.7 % of adults experienced an episode of the Major Depressive Disorder in 2015.

- Health and Care Excellence in Depression Management The introduction of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines can affect the accuracy of diagnosing and quality of managing depression.

- Theories in Depression Treatment This study analyzes the theories pertinent to depression treatment, reviews relevant evidence, defines key concepts of the project, and explains the framework chosen for it.

- Impact of COVID-19 on Depression and Suicide Rates among Adolescents and Young People The purpose of this paper is to explore the influence of coronavirus on these tragic numbers.

- Mild Depression: Psychotherapy or Pharmacotherapy The research question in this paper is: in psychiatric patients with mild depression, what is the effect of psychotherapy on health compared with pharmacotherapy?

- Postpartum Bipolar Disorder and Depression The results of the Mood Disorder Questionnaire screening of a postpartum patient suggest a bipolar disorder caused by hormonal issues and a major depressive episode.

- Bipolar Disorder or Manic Depression Bipolar disorder is a mental illness characterized by unusual mood changes that shift from manic to depressive extremes. In the medical field, it`s called manic depression.

- The Improvement of Depression Management The present paper summarizes the context analysis that was prepared for a change project aimed at the improvement of depression management.

- Depression Management in US National Guidelines The project offers the VEGA medical center to implement the guidelines for depression management developed by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.

- Women’s Health and Major Depression Symptoms The client’s complaints refer to sleep problems, frequent mood swings (she gets sad a lot), and the desire to stay away from social interactions.

- Predictors of Postpartum Depression: Who Is at Risk? The article “Predictors of Postpartum Depression” by Katon, Russo, and Gavin focuses on the identification of risk factors related to postnatal depression.

- Depression and Its Treatment: Racial and Ethnic Disparities The racial and ethnic disparities in depression treatment can be used for the development of quality improvement initiatives aimed at the advancement of patient outcomes.

- Lamotrigine for Bipolar Depression Management Lamotrigine sold as Lamictal is considered an effective medication helping to reduce some symptoms that significantly affect epileptic and bipolar patients’ quality of life.

- Citalopram, Methylphenidate in Geriatric Depression Citalopram typically ranges among 10-20 antidepressants for its cost-effectiveness and positive effect on patients being even more effective than reboxetine and paroxetine.

- Depression and Self-Esteem Relationship Self-esteem can be defined as an “individual’s subjective evaluation of his or her worth as a person”; it does not necessarily describe one’s real talents.

- Postpartum Depression: Methods for the Prevention Postpartum depression is a pressing clinical problem that affects new mothers, infants, and other family members. The prevalence of postpartum depression ranges between 13 and 19 percent.

- Anxiety and Depression Among Females with Cancer The study investigated the prevalence of and the potential factors of risk for anxiety and/or depression among females with early breast cancer during the first 5 years.

- Post-Partum Depression and Perinatal Dyadic Psychotherapy Post-partum depression affects more than ten percent of young mothers, and a method Perinatal Dyadic Psychotherapy is widely used to reduce anxiety.

- VEGA Medical Center: Detection of Depression Practice guidelines for the psychiatric evaluation of adults, and they can be employed to solve the meso-level problem of the VEGA medical center and its nurses.

- The Postnatal (Postpartum) Depression’ Concept Postnatal or postpartum depression (PPD) is a subtype of depression which is experienced by women within the first half a year after giving birth.

- Postpartum Depression, Prevention and Treatment Postpartum depression is a common psychiatric condition in women of the childbearing age. They are most likely to develop the disease within a year after childbirth.

- Smoking Cessation and Depression Problem The aim of the study is to scrutinize the issues inherent in the process of smoking cessation and align them with the occurrence of depression in an extensive sample of individuals.

- Evidence-Based Pharmacology: Major Depression In this paper, a certain attention to different treatment approaches that can be offered to patients with depression will be paid, including the evaluation of age implications.

- The Efficacy of Medication in Depression’ Treatment This paper attempts to provide a substantial material for the participation in an argument concerning the clinical effectiveness of antidepressant medications.

- Depression and Cognitive Psychotherapy Approaches Cognitive psychotherapy offers various techniques to cope with emotional problems. This paper discusses the most effective cognitive approaches.

- Treatment of Depression in Lesbians The aim of this paper is to review a case study of 45 years old lesbian woman who seeks treatment for depression and to discuss the biophysical, psychological, sociocultural, health system.

- Women’s Health: Predictors of Postpartum Depression The article written by Katon, Russo, and Gavin is focused on women’s health. It discusses predictors of postpartum depression (PPD), including sociodemographic and clinic risk factors.

- Depression Treatment and Management Treatment could be started only after patient is checked whether he has an allergy to the prescribed pills or not. If he is not allergic, he should also maintain clinical tests for depression.

- Counseling Depression: Ethical Aspects This paper explores the ethical aspects required to work with a widower who diminished passion for food, secluding himself in the house, portraying signs of depression.

- Postpartum Depression as Serious Mental Health Problem The research study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of a two-step behavioral and educational intervention on the symptoms of postpartum depression in young mothers.

- European Alliances, Wars, Dictatorships and Depression The decades leading to World War I had unusual alignments. The European nations were still scrambling for Asia, Africa and parts of undeveloped Europe.

- Women’s Health: Depression as a Psychological Factor Women who identify themselves as lesbian are likely to experience depression. Biophysical, psychological, sociocultural, behavioral, and health system factors should be taken into consideration.

- Childhood Obesity and Depression Intervention The main intervention to combat depressive moods in adolescents should be linked to improving the psychological health of young people in cooperation with schools.

- Postpartum Depression: Prevalence, Risks, and Impact The paper analyzes the prevalence and risk factors of Postnatal (Postpartum) Depression as well as investigates the effect on the newborns whose mothers suffer from this condition.

- Smoking Cessation and Depression It was estimated that nicotine affects the human’s reward system. As a result, smoking cessation might lead to depression and other mental disorder.

- Placebo and Treatments for Depression Natural alternative treatments for depression actually work better than the biochemical alternatives like antidepressants.

- Care for Depression in Obstetrics and Gynecology This work analyzes the article developed by Melville et al. in which discusses the theme of depression in obstetrics and gynecology and improving care for it.

- Effective Depression Screening in Long-Term Conditions Screening for depression in patients suffering from long term conditions (LTCs) or persistent health problems of the body, could largely be erroneous.

- Patients with Depression’ Care: Betty Case Betty, a 45 years old woman, is referred to a local clinic because of feeling depressed. She has a history of three divorces and thinks that she is tired of living the old way.

- Clinical Depression Treatment: Issues and Solvings The paper describes and justifies the design selected for research on depression treatment. It also identifies ethical issues and proposes ways of addressing them.

- Effectiveness of Integrative and Instrumental Reminiscence Therapies on Depression This article presents the research findings of a study conducted in Iran to assess how effective integrative and instrumental therapies are in the management of depression in older persons.

- Major Types of Depression This paper will review and analyze two scholarly articles concerning depression, its sings in male and female patients, and its connection and similarity to other disorders.

- Depression in the Elderly – Psychology This paper discusses how a person would know whether a relative had clinical depression or was sad due to specific changes or losses in life.

- Depression in the Elderly Depression can be defined as a state of anxiety, sadness, hopelessness, and worthlessness. It can affect people across all ages, who present with diverse signs and symptoms

- Postnatal Depression: Prevalence of Postnatal Depression in Bahrain The study was aimed at estimating the prevalence of postnatal depression among 237 Bahraini women who attended checkups in 20 clinical centres over a period of 2 months.

Cite this post

- Chicago (N-B)

- Chicago (A-D)

StudyCorgi. (2021, September 9). 233 Depression Research Topics & Essay Titles + Examples. https://studycorgi.com/ideas/depression-essay-topics/

"233 Depression Research Topics & Essay Titles + Examples." StudyCorgi , 9 Sept. 2021, studycorgi.com/ideas/depression-essay-topics/.

StudyCorgi . (2021) '233 Depression Research Topics & Essay Titles + Examples'. 9 September.

1. StudyCorgi . "233 Depression Research Topics & Essay Titles + Examples." September 9, 2021. https://studycorgi.com/ideas/depression-essay-topics/.

Bibliography

StudyCorgi . "233 Depression Research Topics & Essay Titles + Examples." September 9, 2021. https://studycorgi.com/ideas/depression-essay-topics/.

StudyCorgi . 2021. "233 Depression Research Topics & Essay Titles + Examples." September 9, 2021. https://studycorgi.com/ideas/depression-essay-topics/.

These essay examples and topics on Depression were carefully selected by the StudyCorgi editorial team. They meet our highest standards in terms of grammar, punctuation, style, and fact accuracy. Please ensure you properly reference the materials if you’re using them to write your assignment.

This essay topic collection was updated on June 21, 2024 .

- CLASSIFIEDS

- Advanced search

American Board of Family Medicine

Advanced Search

A Qualitative Study of Depression in Primary Care: Missed Opportunities for Diagnosis and Education

- Find this author on Google Scholar

- Find this author on PubMed

- Search for this author on this site

- Figures & Data

- Info & Metrics

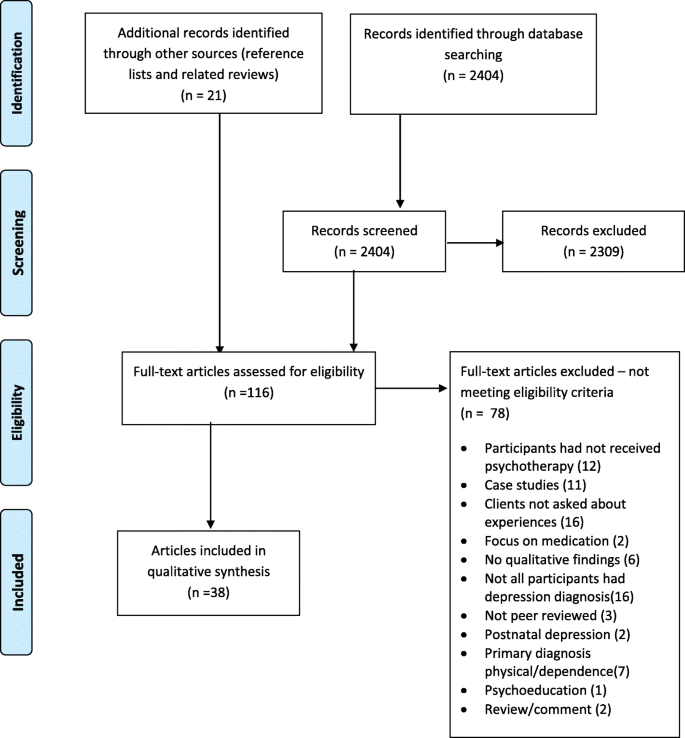

Purpose: Depression is one of the most commonly encountered chronic conditions in primary care, yet it remains substantially underdiagnosed and undertreated. We sought to gain a better understanding of barriers to diagnosis of and entering treatment for depression in primary care.

Methods: We conducted and analyzed interviews with 15 subjects currently being treated for depression recruited from primary care clinics in an academic medical center and an academic public hospital. We asked about experiences with being diagnosed with depression and starting treatment, focusing on barriers to diagnosis, subject understanding of depression, and information issues related to treatment decisions.

Results: Subjects reported many visits to primary care practitioners without the question of depression being raised. The majority had recurrent depression. Many reported that they did not receive enough information about depression and its treatment options. In the majority of cases, practitioners decided the course of treatment with little input from the patients.

Conclusions: In this sample of depressed patients, we found evidence of frequent missed diagnoses, substantial information gaps, and limited patient understanding and choice of treatment options. Quality improvement efforts should address not only screening and follow-up but patient education about depression and treatment options along with elicitation of treatment preferences.

Depression is a common mental health problem leading to significant morbidity and mortality and high medical and societal costs. 1–3 The World Health Organization estimated that major depression caused more disability worldwide in 1990 than ischemic heart disease or cerebrovascular disease. 4 The prevalence of major depressive disorders in the US population aged 18 years and older has been estimated at 5%, 5 and it is one of the most commonly encountered conditions in primary care, 6 ,7 but up to 50% of cases go unrecognized. 8 ,9 In many cases, it is more appropriately viewed as a chronic disorder with remissions and relapses than an acute illness. 10–12

Even if diagnosed, care for depression is frequently flawed. Many persons diagnosed with depression do not commence treatment for it, 9 and the majority of persons who do enter treatment do not receive their preferred type of treatment, even though this seems to lead to better outcomes. 13 ,14 Furthermore, many persons starting treatment do not complete an adequate treatment course. 15 The US Preventive Services Task Force “recommends screening adults for depression in clinical practices that have systems in place to assure accurate diagnosis, effective treatment, and follow-up” with a grade B recommendation, 16 as such systems have been demonstrated to improve health status and, in some instances, to reduce health care costs. 17–20

There is a remarkable paucity of information about patients’ understanding of depression and its treatment options, and the role patients play in choosing treatment options. The very limited evidence available suggests quite modest benefits of patient education materials for depression in isolation from more comprehensive interventions. 21 ,22 Some studies have included patient informational materials as part of a systematic intervention, but not evaluated them separately. 14 ,17 ,19 In some cases, patient education materials may have more of a medical than a patient-centered orientation and may not address a number of patients’ key questions. 23

In this study, we report results of qualitative analyses of interviews with patients currently under treatment for depression about their experiences with being diagnosed with and starting treatment for depression. We specifically sought to explore their understanding of depression before and after receiving the diagnosis, sources and adequacy of information about depression and its treatment options, and their roles in choosing treatment options. We chose a qualitative approach because of the limited extant information in this area to “map the terrain” and be open to unexpected findings.

Participant Recruitment

Subjects were recruited by posting flyers in primary care clinics affiliated with the University of Washington Medical Center, an academic medical center, and at Harborview Medical Center, a public/teaching hospital affiliated with the University of Washington. We advertised for persons who had been diagnosed with depression within the past year. Persons who had been diagnosed with depression, spoke English, and were able to give informed consent were eligible to participate in the study. This study was approved by the University of Washington’s Human Subjects Institutional Review Board.

Conduct of Interviews

We conducted semistructured, qualitative interviews lasting 30 to 60 minutes with 15 subjects currently undergoing treatment for depression. Subjects were interviewed by 2 study members, with one acting as primary interviewer and the other focusing more on detailed note taking, with the exception of 3 cases where only 1 team member was available. A family physician-investigator (BGS) participated in 11 of the 15 interviews. The backgrounds of the other interviewers were education (VV-N) and public health (GK). Each interviewer took typewritten notes during the interviews, touch typing and maintaining eye contact with subjects and only rarely asking for brief pauses to catch up on note taking. Notes were checked for consistency and merged after the interviews.

Interviews were structured around a set of root questions covering subjects’ experience of and perspectives on being diagnosed with depression, receiving information about the diagnosis, receiving information about treatment options, and deciding to start treatment for depression. Each root question was followed by a number of probe questions to flesh out detail in subjects’ responses. Subjects were asked about their current episode of depression and any previous episodes. The template for the root and probe questions is contained in the Appendix.

Data Analysis

We used a qualitative descriptive approach 24 based on our interview template. Using notes from the first 3 interviews, 3 researchers (BGS, VV-N, and GK) who participated in the interviewing process independently classified statements according to this schema, first into the major categories underlying our interview template and then into subcategories as we identified them in the data. We added new categories and subcategories for statements not fitting this framework, and searched for themes and concepts common to these interviews. These 3 researchers then compared results and, through an interactive process of discussion, reflection, and scrutiny of the interview template, interview notes, and initial coding, arrived at consensus on a refined coding scheme. Using this coding scheme, 2 researcher-interviewers (VV-N and GK) independently coded the remaining interview notes using QSR NVivo 2.0 (Qualitative Systems and Research, Australia, 2002) and met to compare different perspectives and interpretations of ambiguous data and identification of concepts not covered by the coding scheme; differences were reconciled with no significant disagreements. The other researcher-interviewer (BGS) reviewed all the notes and coding for consistency and to ensure that no significant concepts or themes had been overlooked or statements misclassified or left uncoded. This resulted in coding of a few additional statements with the existing coding scheme but no new categories or disagreements with the coding assignments.

Given our a priori descriptive goals, we did not seek to generate new theories about depression in primary care; rather, we focused on describing common experiences and identifying gaps and barriers that might be amenable to interventions to improve depression care for future patients.

The 15 participants ranged in age from their mid-20s to their late 50s, with about half in their mid-40s, and were evenly split between males and females. There were 7 Caucasian, 6 African American, 1 Asian American, and 1 Native American subjects. Six participants reported college or graduate degrees, and 6 more reported some college education. Four subjects mentioned a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, 3 reported anxiety disorders, and 5 gave histories of substance use problems. We chose to retain and analyze interviews with participants reporting a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, because their reported experiences with depression diagnosis and treatment were quite similar to those of our participants not reporting a bipolar diagnosis, and depression is a common presentation of bipolar disorder. Similarly, we have retained the participants in our sample who reported histories of substance use as the issues raised by these participants were very much the same as those raised by other participants, with the addition of active substance use being a barrier to willingness to undertake treatment for depression.

A majority of our participants reported being diagnosed with depression by a mental health care practitioner, but a substantial minority reported receiving an initial diagnosis from a primary care practitioner (PCP). One third reported their initial diagnosis came as a result of an emergency department visit. All subjects reported limited understanding of depression before their initial diagnosis. None reported having, before diagnosis, acquaintance with views of depression as a frequently heritable condition involving neurotransmitters in the brain, regardless of their educational attainment. Sample comments illustrating subjects’ reported understanding of depression before their initial diagnoses are presented in Table 1 .

- View inline

Participant Statements about Prediagnosis Understanding of Depression

Participants frequently reported incidents of missed diagnosis during visits to PCPs. As exemplified by quotes in Table 2 , reasons cited for missed diagnoses fell into 2 categories: patient-related and practitioner-related factors. Some subjects expressed either inability or unwillingness to raise the issue with their practitioners. Others reported that practitioners were unsuspecting, focusing on the subjects’ somatic complaints (depression-related or otherwise), seemed uninterested in the possibility of nonphysical issues, or were frankly dismissive of the diagnosis when the subject raised it with them.

Participant Statements about Missed Diagnoses of Depression

Only a few participants reported receiving helpful verbal information from their PCPs, also in some cases accompanied by being referred to a patient information library; most reported receiving little or no information from their PCPs about depression. Of the 13 participants who had seen a mental health care practitioner at any point, a majority reported receiving information about depression; a minority felt the information they received from mental health professionals was inadequate. Some subjects reported seeking out information from other sources, such as books, broadcast media, and the internet. Representative comments about sources of information about the diagnosis of depression are shown in Table 3 .

Participant Statements Regarding Sources of Information about Depression

A number of subjects reported having received written information, but this information was frequently recalled as not very helpful. The participants who reported doing their own research about depression proved more informed about current understanding of the genetics and neurobiology of depression than those who had not. Two persons specifically commented that learning about this helped them stop blaming themselves for their depression (see quotes in Table 3 ).

Many participants reported barriers to obtaining information about depression and its treatment. These could be grouped into several categories: lack of motivation due to depression, stigma of depression and/or denial of the diagnosis, practitioners seeming unresponsive, and a mismatch between their preferred mode of learning and how information was offered. Quotes exemplifying these issues are provided in Table 4 .

Participant Statements about Barriers to Getting Information about Depression

Fewer than half of our subjects reported being given any information about counseling as a treatment option. None remembered being given any explanation of what counseling options, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, problem-solving therapy, and interpersonal therapy, might be like.

Only a minority of the participants indicated that they felt they had had some say in their treatment decisions and even where they did, not all felt they had sufficient information to make a good choice. However, not all wanted to make this choice, with some preferring to trust their practitioners to make the choice. Quotes pertaining to issues of role in choice of therapy are shown in Table 5 .

Participant Statements about Participation in Treatment Decisions

Because almost 75% of patients who seek help for depression do so in primary care settings, 3 substantial improvement in the quality of care for depression must address deficits in primary care. Our interviews highlight some key areas where depression care might be improved: screening for depression; patient education about current understanding of depression and treatment options; improving provider attitudes and knowledge about depression and its treatment where there are gaps; and increasing the collaborative nature of decision making about treatment options.

Our participants reported frequent missed diagnoses, even among persons with recurrent depression. Although one might debate the value of universal screening, particularly in the widespread absence of “systems in place to assure accurate diagnosis, effective treatment, and follow-up,” 16 use of practice-based information systems to implement screening for recurrent depression among persons with past diagnoses might well be efficient and cost-effective in the current practice environment.

As noted above, the limited evidence on educational interventions for depression 21 ,22 does not suggest that education alone is likely to be particularly effective in improving outcomes of depression treatment. However, education is a key component of self-management support, facilitating patients in taking active roles in commencing and continuing treatment. Our participants reported that they generally received limited information from practitioners about depression and the treatment options available, both in primary care and mental health care settings. Most reported that they would have liked more information. A number of barriers to obtaining information were reported, with both patient-related and practitioner-related factors appearing important.

Although this study did not specifically address stigma associated with depression, several of our participants raised this issue. and other studies have shown that stigma is a major barrier to diagnosis and treatment of depression. 3 ,25–28 Education may help to reduce personal stigma associated with depression. 22

Most of our participants reported that they would have liked more say in their choice of treatments. Implementing systems to solicit treatment preferences of persons diagnosed with depression and coordination with counseling resources could substantially improve outcomes given the evidence that providing patients with their preferred mode of treatment increases both treatment uptake and adherence 13 ,14 and that more patients seem to desire counseling versus medication for treatment of depression. 29–31

A number of limitations of this study must be acknowledged. First, being based on a limited number of interviews with volunteer participants recruited from outpatient clinics at 2 hospitals associated with a single teaching institution, we cannot know how well our finding generalize to the universe of persons under treatment for depression in the US. Both sites probably have an overrepresentation of persons with significant, chronic mental health issues. Volunteers may well differ in many ways from “average” patients with depression. Second, recall of our participants may have been incomplete and/or biased. Depression can interfere with both memory and motivation, so it is possible that some subjects received information and/or choices that they did not recall during the interviews. Third, as with most research, our findings and conclusions are subject to potential bias from our preconceptions and prejudices. Our budget did not permit transcription of interview recordings and we did not record the interviews, so choices about what to record in our notes could influence our findings. However, having 2 persons simultaneously take notes in 12 of the 15 cases should have minimized effects of selective recording of information. Fourth, having only interviewed persons engaged in active treatment for depression, we cannot generalize our findings to those who declined or stopped therapy. Fifth, we had anticipated our participants would primarily be persons who had received new diagnoses of depression in the primary care setting within the previous year, but many had chronic or recurrent depression and were seeing or had seen mental health practitioners. Our interview template did not have probes to clearly delineate the separate roles of primary care and mental health specialty care and the coordination of care between them. Sixth, we have no way of knowing whether addressing the shortcomings in diagnosis and patient education about depression we have identified will, in fact, improve outcomes of depression treatment.

However, our findings are consistent with existing literature on shortcomings in diagnosis and treatment of depression. Addressing these deficits would enhance the patient-centeredness of care for depression and offers the potential to improve engagement with and outcomes of treatment for depression.

Background Information

Years diagnosed with depression

6. How was your depression diagnosed?

Did you go to the doctor specifically because you thought you were depressed and wanted help?

If not, what made you go to the doctor?

Had you been to the doctor earlier, while you were depressed, without having the question of depression brought up?

If so, why do you think it didn’t come up?

Had you been diagnosed with or treated for depression previously?

Recognizing Depression:

7. What was your understanding of depression before you were diagnosed?

Source of information/understanding depression

8. What information were you given about depression?

What information were you given when the diagnosis was made?

How was it given? For example, did the doctor talk with you to help you understand about depression? Were you given written materials? Referred to books, web resources, or something else?

Did you feel you had enough information?

If not, what else did you want to know?

What prevented you from learning more? (For example, no time left in the visit, information was too hard to understand at the time, information was just not offered, or other.)

Information on treatment options

9. Did you feel you were given enough information about treatment options to make a good choice?

Did you learn about both counseling and medications?

Did you understand what counseling for depression generally involves?

Did you hear about the different types of antidepressant medications (such as tricyclic antidepressants and SSRIs) and the pros and cons of each?

How was the information provided? For example, did the doctor talk with you? Were you given written materials? Referred to books, web resources, or something else?

Did you feel you had enough information to make a good choice?

If not, what else would you have liked to know?

Treatment decision

10. After the discussion of depression as a diagnosis, did you decide to start treatment?

If not then why not?

Did you later start treatment? If so, why?

What had changed?

If no change then explain why?

Continued treatment

11. If you started treatment, how soon after this was your next contact with your provider?

12. Did you initiate the contact or did they? (E.g., someone from your doctor’s office called you or they scheduled a follow-up appointment a week or two after you decided to start treatment.)

13. Do you have any thoughts about things that would have improved the diagnosis and treatment of your depression? This might be helping it be diagnosed sooner, helping you understand the diagnosis better, helping you understand treatment options better, helping you start treatment, or helping you stick with treatment.

14. Do you have any other thoughts about how doctors can do a better job helping people with depression?

This article was externally peer-reviewed.

Prior presentation : A portion of this work was presented at the 33rd North American Primary Care Research Group Annual Meeting, Quebec City, Quebec, October 15–18, 2005.

Conflict of interest : none reported.

- Received for publication February 8, 2006.

- Revision received September 27, 2006.

- Accepted for publication October 5, 2006.

- ↵ Simon G, Ormel J, VonKorff M, Barlow W. Health care costs associated with depressive and anxiety disorders in primary care. Am J Psychiatry 1995 ; 152 : 352 –7. OpenUrl PubMed

- Stewart WF, Ricci JA, Chee E, Hahn SR, Morganstein D. Cost of lost productive work time among US workers with depression. JAMA 2003 ; 289 : 3135 –44. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Goldman LS, Nielsen NH, Champion HC. Awareness, diagnosis, and treatment of depression. J Gen Intern Med 1999 ; 14 : 569 –80. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Alternative projections of mortality and disability by cause 1990–2020: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 1997 ; 349 : 1498 –504. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Regier DA, Narrow WE, Rae DS, et al. The de facto US mental and addictive disorders service system: epidemiologic catchment area prospective 1-year prevalence rates of disorders and services. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993 ; 50 : 85 –94. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Nelson C, Woodwell D. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 1993 summary. Vital Health Stat 1998 ; 13 : 1 –99. OpenUrl

- ↵ Stange KC, Zyzanski SJ, Jaen CR, et al. Illuminating the “black box”: a description of 4454 patient visits to 138 family physicians. J Fam Pract 1998 ; 46 : 377 –89. OpenUrl PubMed

- ↵ Depression Guideline Panel. Depression in Primary Care: Vol. 1. Detection and Diagnosis. Clinical Practice Guideline, No. 5. 1993, US Department of Health and Human Services: Rockville, MD.

- ↵ Simon GE, VonKorff M. Recognition, management, and outcomes of depression in primary care. Arch Fam Med 1995 ; 4 : 99 –105. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Judd LL. The clinical course of unipolar major depressive disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997 ; 54 : 989 –91. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- Glass RM. Treating depression as a recurrent or chronic disease. Jama 1999 ; 281 : 83 –4. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- Ludman E, Von Korff M, Katon W, et al. The design, implementation, and acceptance of a primary care-based intervention to prevent depression relapse. Int J Psychiatry Med 2000 ; 30 : 229 –45. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Lin P, Campbell DG, Chaney EF, et al. The influence of patient preference on depression treatment in primary care. Ann Behav Med 2005 ; 30 : 164 –73. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Dwight-Johnson M, Unutzer J, Sherbourne C, Tang LQ, Wells KB. Can quality improvement programs for depression in primary care address patient preferences for treatment? Med Care 2001 ; 39 : 934 –44. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Von Korff M, Goldberg D. Improving outcomes in depression. BMJ 2001 ; 323 : 948 –9. OpenUrl FREE Full Text

- ↵ U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for depression: recommendations and rationale. Ann Intern Med 2002 ; 136 : 760 –4. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, et al. Collaborative management to achieve treatment guidelines: impact on depression in primary care. JAMA 1995 ; 273 : 1026 –31. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- Katzelnick DJ, Simon GE, Pearson SD, et al. Randomized trial of a depression management program in high utilizers of medical care. Arch Fam Med 2000 ; 9 : 345 –51. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Simon GE, Katon WJ, VonKorff M, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a collaborative care program for primary care patients with persistent depression. Am J Psychiatry 2001 ; 158 : 1638 –44. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- Simon GE, Manning WG, Katzelnick DJ, et al. Cost-effectiveness of systematic depression treatment for high utilizers of general medical care. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001 ; 58 : 181 –7. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Jorm AF, Griffiths KM, Christensen H, et al. Providing information about the effectiveness of treatment options to depressed people in the community: a randomized controlled trial of effects on mental health literacy, help-seeking and symptoms. Psychol Med 2003 ; 33 : 1071 –9. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Griffiths KM, Christensen H, Jorm AF, Evans K, Groves C. Effect of web-based depression literacy and cognitive-behavioural therapy interventions on stigmatising attitudes to depression: randomised controlled trial. Brit J Psychiatry 2004 ; 185 : 342 –9. OpenUrl Abstract / FREE Full Text

- ↵ Grime J, Pollock K. Information versus experience: a comparison of an information leaflet on antidepressants with lay experience of treatment. Patient Educ Couns 2004 ; 54 : 361 –8. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description?. Res Nurs Health 2000 ; 23 : 334 –40. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Collins KA, Westra HA, Dozois DJA, Burns DD. Gaps in accessing treatment for anxiety and depression: challenges for the delivery of care. Clin Psychol Rev 2004 ; 24 : 583 –616. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- Unutzer J. Diagnosis and treatment of older adults with depression in primary care. Biol Psychiatry 2002 ; 52 : 285 –92. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- Schwenk TL. Diagnosis of late life depression: the view from primary care. Biol Psychiatry 2002 ; 52 : 157 –63. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- Docherty JP. Barriers to the diagnosis of depression in primary care. J Clin Psychiatry 1997 ; 58 Suppl 1 : 5 –10. OpenUrl

- ↵ Brody DS, Khaliq AA, Thompson TL, II. Patients’ perspectives on the management of emotional distress in primary care settings. J Gen Intern Med 1997 ; 12 : 403 –6. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- Dwight-Johnson M, Sherbourne CD, Liao D, Wells KB. Treatment preferences among depressed primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med 2000 ; 15 : 527 –34. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- Cooper LA, Gonzales JJ, Gallo JJ, et al. The acceptability of treatment for depression among African-American, Hispanic, and white primary care patients. Med Care 2003 ; 41 : 479 –89. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

In this issue

- Table of Contents

- Index by author

Thank you for your interest in spreading the word on American Board of Family Medicine.

NOTE: We only request your email address so that the person you are recommending the page to knows that you wanted them to see it, and that it is not junk mail. We do not capture any email address.

Citation Manager Formats