Pengertian Metode Observasi dan Contohnya

Pengertian Metode Observasi dan Contohnya – Setiap peneliti tentunya mencurahkan perhatiannya kepada sesuatu dan mengamati fakta yang terdapat di dalamnya. Hal ini tentu saja didorong oleh rasa keingintahuan yang tinggi terkait pemahaman fakta yang diamati secara lebih mendalam. Pada hakikatnya, seorang peneliti pastinya memunculkan berbagai pertanyaan. Pengamatan terhadap fakta, identifikasi atas masalah, dan usaha untuk menjawab rumusan masalah didasarkan pada teori. Hal ini merupakan esensi dari sebuah riset.

Riset dapat disebut sebagai suatu usaha yang sistematis untuk mengatur dan menyelidiki masalah serta menjawab pertanyaan yang muncul dan terkait dengan fakta dan fenomena. Oleh karena itu, riset merupakan hal yang sangat penting karena berupa penyelidikan yang sistematis, terkontrol, empiris dan kritis tentang fenomena alami dengan dipandu oleh teori dan hipotesis mengenai hubungan yang dianggap terdapat di antara fenomena itu.

Berdasarkan teknik, pengolahan data dalam sebuah penelitian dibagi menjadi dua, yaitu penelitian kuantitatif dan penelitian kualitatif. Salah satu teknik pengolahan data yang seringkali digunakan dalam penelitian, yaitu teknik observasi. Observasi ini memiliki peran penting dalam arti penelitian sebagai salah satu metode penelitian ilmiah yang dapat dilakukan dengan bermacam-macam cara. Namun, kebutuhan untuk reproduktifitas mensyaratkan bahwa observasi oleh pengamat yang berbeda dapat dibandingkan.

Dalam suatu penelitian, metode observasi akan digambarkan sebagai metode yang dipergunakan dalam mengamati dan mendeskripsikan tingkah laku subjek. Seperti namanya, observasi ini adalah cara mengumpulkan informasi dan data yang relevan dengan mengamati, sehingga dalam hal ini observasi disebut sebagai studi partisipatif karena si peneliti harus menjalin hubungan dengan responden dan untuk ini harus membenamkan dirinya dalam pengaturan yang sama dengan mereka.

Hanya dengan begitu peneliti dapat menggunakan metode observasi untuk mencatat data yang dibutuhkan. Metode observasi digunakan jika peneliti ingin menghindari kesalahan yang dapat menjadi hasil bias selama proses evaluasi dan interpretasi. Penggunaan teknik observasi ini biasanya dijadikan sebagai pendukung dalam suatu riset untuk mengamati fenomena yang terjadi di lokasi penelitian.

Terdapat bermacam-macam teknik yang dipergunakan dalam observasi oleh seorang peneliti sesuai kebutuhan data yang ingin mereka dapatkan. Kira-kira apa saja teknik-teknik yang seringkali digunakan untuk keperluan observasi dalam sebuah penelitian?

Dalam artikel kali ini, kita akan membahas mengenai teknik observasi sebagai salah satu contoh dari teknik pengolahan data. Dengan harapan bisa menjadi tambahan insight dan rekomendasi bagi kalian calon praktisi data, peneliti, maupun data enthusiast . Jangan lewatkan artikel berikut ini, pastikan simak baik-baik, stay tune and keep scrolling on this article guys!

Mengungkap Rahasia Sukses Leonard Hartono dalam Buku A Book by Overpost: Business 101

Pengertian Observasi

Metode observasi seringkali menjadi pelengkap data yang diperoleh dari wawancara mendalam dan survei. Observasi bisanya dipahami sebagai upaya untuk memperoleh data secara ”natural”. Pengertian paling sederhana dari metode observasi adalah melihat dan mendengarkan peristiwa atau tindakan yang dilakuakan oleh orang-orang yang diamati, kemudian merekam hasil pengamatannya dengan catatan atau alat bantu lainnya.

Observasi berarti pula mengamati, menyaksikan, memperhatikan sebagai metode pengumpulan data penelitian. Artikel ini akan membahas tentang metode observasi dalam penelitian sosial. Kita sudah mendefinsikan secara sederhana apa itu observasi di paragraf pertama. Berikutnya, kita akan ulas secara lebih mendalam tentang cara melakukan observasi dan masalah yang biasanya dihadapi peneliti.

Tak jarang, metode observasi dipahami secara keliru. Observasi memang mengamati dengan melihat dan mendengar. Namun, observasi sebagai metode penelitian memiliki karakteristik dan teknik tertentu. Barangkali beberapa pembaca sudah pernah mendengar istilah observasi partisipatoris. Kita akan ulas tentang pengertian observasi menurut para ahli dan jenis-jenis observasi sebelum membahas masalah dalam metode observasi.

Dikutip dari buku Evaluasi Pembelajaran: Konsep Dasar, Prinsip, Teknik, dan Prosedur (2020) oleh Muhammad Ilyas Ismail, observasi adalah salah satu teknik pengumpulan data yang sifatnya lebih spesifik dibanding teknik lainnya. Beberapa pengertian observasi menurut para ahli adalah sebagai berikut:

1. Gibson R.L. dan Mitchell M.H.

Observasi merupakan teknik yang digunakan sebagai seleksi derajat untuk menentukan sebuah keputusan serta konklusi terhadap orang yang sedang diamati.

2. Larry Christensen

Observasi adalah cara untuk mendapatkan informasi penting mengenai orang, karena apa yang dikatakan belum tentu sesuai dengan yang dikerjakan.

3. Creswell

Observasi adalah proses pemerolehan data dari tangan pertama, dengan cara melakukan pengamatan orang serta lokasi dilakukannya penelitian.

Observasi merupakan metode yang sifatnya akurat dan spesifik untuk mengumpulkan data dan mencari informasi mengenai segala kegiatan yang dijadikan obyek kajian penelitian.

5. Sutrisno Hadi

Obervasi merupakan sebuah proses yang sangat kompleks, terdiri atas berbagai macam proses, baik biologis maupun psikologis, yang mana lebih memprioritaskan proses ingatan serta pengamatan.

6. Eko Putro Widyoko

Observasi adalah pengamatan dan pencatatan secara sistematis terhadap unsur-unsru yang tampak dalam suatu gejala pada obyek penelitian.

7. Sugiyono

Dikutip dari buku Metode Penelitian Pendidikan Pendekatan Kuantitatif (2014), observasi adalah proses yang kompleks, suatu proses yang tersusun dari pelbagai proses biologis dan psikologis.

Dalam bukunya Metodologi Penelitian Pendidikan (2010), dijelaskan bahwa observasi merupakan metode pengumpulan data yang menggunakan pengamatan secara langsung maupun tidak langsung.

Teknik dalam Observasi

1. observasi terkontrol.

Observasi terkontrol dilakukan di ruang tertutup. Peneliti yang memiliki kewenangan untuk menentukan tempat dan waktu di mana dan kapan observasi akan dilakukan. Dia juga memutuskan siapa partisipannya dan dalam keadaan apa dia akan menggunakan proses standar.

Partisipan dipilih untuk kelompok variabel penelitian secara acak. Peneliti mengamati dan mencatat data perilaku yang rinci dan deskriptif dan membaginya ke dalam kategori yang berbeda. Kadang-kadang peneliti mengkodekan tindakan sesuai skala yang disepakati dengan menggunakan daftar perilaku.

Pengkodean dapat mencakup huruf atau angka atau rentang untuk mengukur intensitas perilaku dan menggambarkan karakteristiknya. Data yang terkumpul seringkali diubah menjadi statistik. Dalam metode observasi terkontrol, partisipan diinformasikan oleh peneliti tentang tujuan penelitian. Hal ini membuat mereka sadar sedang diamati. Peneliti menghindari kontak langsung selama metode observasi dan umumnya menggunakan cermin dua arah untuk mengamati dan mencatat detail.

2. Observasi Partisipatif

Metode observasi partisipatif sering dianggap sebagai varian dari metode observasi naturalistik karena memiliki kemiripan. Perbedaannya adalah peneliti bukan lagi pengamat jarak jauh karena ia telah bergabung dengan partisipan dan menjadi bagian dari kelompoknya.

Seorang peneliti melakukan ini untuk mendapatkan wawasan yang lebih mendalam dan lebih dalam tentang kehidupan mereka. Peneliti berinteraksi dengan anggota lain dari kelompok secara bebas, berpartisipasi dalam aktivitas mereka, mempelajari perilaku mereka dan memperoleh cara hidup yang berbeda. Pengamatan partisipan bisa terbuka atau terselubung.

- Overt (terbuka), ketika peneliti meminta izin dari suatu kelompok untuk berbaur. Ia melakukannya dengan mengungkapkan tujuan sebenarnya dan identitas aslinya kepada kelompok yang ingin diajak bergaul.

- Covert (terselubung), jika peneliti tidak menunjukkan identitas atau arti sebenarnya kepada kelompok yang ingin ia ikuti. Ia merahasiakan keduanya dan mengambil peran dan identitas palsu untuk masuk dan berbaur dalam grup. Dia biasanya bertindak seolah-olah dia adalah anggota asli dari grup itu

3. Observasi Naturalistik

Ilmuwan sosial dan psikolog umumnya menggunakan metode observasi naturalistik. Prosesnya melibatkan mengamati dan mempelajari perilaku spontan para partisipan di lingkungan terbuka atau alami. Peran peneliti adalah menemukan dan merekam apa saja yang dapat dilihat dan diamati di habitat aslinya.

Teknik ini melibatkan pengamatan dan mempelajari perilaku spontan partisipan di lingkungan alami mereka. Peneliti hanya mencatat apa yang mereka lihat dengan cara apapun yang mereka bisa. Dalam observasi tidak terstruktur, peneliti mencatat semua perilaku yang relevan tanpa sistem. Mungkin ada terlalu banyak untuk dicatat dan perilaku yang dicatat belum tentu menjadi yang paling penting, sehingga pendekatan ini biasanya digunakan sebagai studi percontohan untuk melihat jenis perilaku apa yang akan dicatat. Dibandingkan dengan pengamatan terkontrol, ini seperti perbedaan antara mempelajari hewan liar di kebun binatang dan mempelajarinya di habitat aslinya.

4. Observasi Terstruktur

Observasi terstruktur terdiri atas definisi kategori yang cermat di mana informasi akan dicatat, standarisasi kondisi pengamatan, dan sebagian besar digunakan dalam studi yang dirancang untuk memberikan deskripsi sistematis atau untuk menguji hipotesis kausal.

Penggunaan teknik observasi terstruktur mengandaikan bahwa penyidik mengetahui aspek apa dari situasi yang diteliti yang relevan dengan tujuan penelitiannya dan oleh karena itu berada dalam posisi untuk mengembangkan rencana khusus untuk membuat dan merekam pengamatan sebelum dia benar-benar memulai pengumpulan data.

Pengamatan terstruktur dapat digunakan dalam pengaturan lapangan alami atau pengaturan laboratorium. Pengamatan terstruktur, sejauh ini digunakan terutama dalam penelitian yang dimulai dengan formulasi yang relatif spesifik, biasanya memungkinkan kebebasan memilih yang jauh lebih sedikit sehubungan dengan isi pengamatan daripada yang diizinkan dalam pengamatan tidak terstruktur.

Dikarenakan situasi dan masalahnya sudah eksplisit, pengamat berada dalam posisi untuk menetapkan terlebih dahulu kategori-kategori yang akan dianalisis situasi tersebut. Kategori ditentukan dengan jelas untuk memberikan data yang dapat diandalkan tentang pertanyaan yang akan ditanyakan.

Contoh Metode Observasi

Pada dasarnya, ada dua jenis metode observasi dalam penelitian; partisipatoris dan non-partisipatoris. Motivasi utama pembedaan ini adalah pada istilah yang disebut tingkat reaktivitas. Reaktivitas sangat menentukan kualitas data penelitian. Kita bisa memahami reaktivitas sebagai seberapa reaktif perilaku orang-orang yang sedang diteliti atau sedang diamati. Semakin reaktif, maka data yang dihasilkan dari observasi semakin rendah kualitasnya. Reaktivitas bisa dilihat pula sebagai sumber error.

Sebagai contoh, kita akan melakukan observasi pada komunitas hijau di Yogyakarta. Dalam konteks natural (tanpa penelitian), ekspresi wajah beberapa anggota komunitas terlihat muram ketika menjalankan kegiatan menanam di kebun. Di hari lain, ketika seorang peneliti dari luar negeri datang untuk melakukan observasi, ekspresi wajah para anggota tersebut terlihat bersemangat sekali. Mimik muka yang terlihat bersemangat itu adalah bentuk reaktivitas karena dilakukan dengan penuh kesadaran bahwa dirinya sedang di bawah pengamatan. Dengan kata lain, tidak ”natural”.

Kualitas data hasil observasi yang tidak ”natural” boleh dikatakan lemah atau bahkan error. Tingkat seberapa reaktif data yang diperoleh nantinya harus dipikirkan terlebih dahulu oleh peneliti sebelum turun lapangan. Setelah menilai potensi reaktivitas, baru peneliti menentukan apakah akan memilih metode observasi partisipatoris atau non-partisipatoris.

1. Metode Observasi Partisipatoris

Metode observasi partisipatoris bisa dideskripsikan sebagai metode pengamatan dimana peneliti memposisikan dirinya sebagai partisipan sebagaimana orang lain yang sedang diobservasi. Dalam memposisikan diri sebagai partisipan, peneliti tetap harus menjaga jarak agar unsur objektivitas tetap terjaga.

2. Metode Observasi Non-Partisipatoris

Metode observasi non-partisipatoris bias dipahami sebagai metode pengamatan dimana peneliti memposisikan diri sebagai orang luar dari kelompok yang ditelitinya. Metode ini sering kali memberi jarak yang cukup jauh antara peneliti dengan objek yang diteliti karena pengamatan dilakukan dari luar. Pada level yang ekstrim, metode non-partisipatoris dapat dilihat sebagai metode yang sering dipraktikkan oleh mata-mata dalam mengamati suatu kasus.

Melanjutkan isu reaktivitas yang telah disinggung di awal, menurut sosiolog Martyn Hammersley dalam tulisannya di The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology (2007) berjudul “Observation”, masalah yang dihadapi metode observasi tidak hanya isu reaktivitas. Beberapa isu lain yang dihadapi peneliti meliputi; problem memperoleh akses, sampling, variasi data yang dihasilkan, dan problem etika.

Cara Mendapatkan Data Hasil Observasi yang Berkualitas

Berikut ini beberapa isu lain yang harus diperhatikan agar data hasil observasi yang diperoleh berkualitas, sehingga hasil riset juga berkualitas.

- Masalah memperoleh akses bisa terdiri dari beragam bentuk, tergantung pada peran yang akan dimainkan peneliti dan keputusan sebjek penelitian. Ketika penelitian dilakukan secara terbuka, artinya peneliti memperkenalkan diri dan risetnya, akses untuk melakukan observasi akan tergantung pada proses negosiasi. Dalam proses negosiasi, kesepakatan terkait penelitian harus dicapai diawal agar tidak ada pihak yang dirugikan nantinya. Persetujuan untuk melakukan observasi bisa pula tergantung pada karakteristik dan kualitas personal dan sosial penelitinya.

- Sampling bisa pula melibatkan observasi. Sebagai contoh, peneliti mengamati situasi kampung atau komunitas yang sedang diteliti, misalnya. Pengamatan awal untuk sampling ini bisa membantu menentukan siapa saja orang yang akan dijadikan informan, kapan mereka bisa ditemui atau dihubungi, dan lain sebagainya. Ada beberapa strategi yang bisa diterapkan di sini, misalnya, apakah peneliti akan meletakkan fokus perhatiannya pada tempat yang diteliti atau perilaku orang-orangnya. Berapa lama melakukan observasi juga harus ditentukan sejak awal.

- Variasi data yang dihasilkan tergantung pada apakah observasi dilakukan secara terstruktur atau tidak terstruktur. Observasi yang terstruktur mengikuti desain perencanaan detail yang dibuat sebelum observasi dilakukan. Dengan kata lain, peneliti melakukan observasi sesuai panduan observasi. Pengamatan yang tidak terstruktur artinya observasi dilakukan secara fleksibel. Data yang dihasilkan dari observasi tak terstruktur biasanya lebih beragam karena melibatkan beberapa instrumen penelitian yang digunakan sesuai kebutuhan, misalnya, buku harian, catatan lapangan, alat rekam suara, alat rekam gambar, alat rekam video, dan sebagainya.

- Masalah etika harus dijelaskan terlebih dahulu di awal agar peneliti tidak tersandung masalah etis yang bisa menurunkan reputasinya sebagai peneliti. Observasi bisa dilakukan secara tertutup atau terbuka. Prosedur etis pada umumnya menghendaki observasi terbuka dimana identitas peneliti dan penelitiannya diketahui oleh orang yang diobservasi. Di lain sisi, observasi tertutup sering ditolak karena biasanya diselimuti kebohongan, misalnya menyembunyikan identitas asli peneliti dan menggunakan identitas palsu. Subjek penelitian juga berpotensi terganggu privasinya. Namun demikian, pilihan apakah akan menerapkan observasi terbuka atau tertutup tergantung pada tingkatannya. Observasi yang terlalu terbuka juga rentan terhadap error.

Keuntungan dan Kekurangan Metode Observasi

Berikut penjelasan keuntungan dan kerugian metode observasi:

1. Keuntungan Observasi

Keuntungan pelaksanaan pengamatan langsung atau observasi dalam proses pengumpulan data, yaitu:

- Observasi sangat mudah dilaksanakan.

- Metode pengamatan langsung mampu menjawab atau memenuhi rasa ingin tahu seseorang, sehingga pada akhirnya proses yang sudah dilalui memberikan makna atau nilai tersendiri. Dengan metode pengamatan langsung bisa menjadi bukti dan tidak adanya manipulasi.

- Observasi bisa membuat seseorang lebih termotivasi dan juga memiliki rasa ingin tahu yang cukup besar. Metode ini bisa digunakan sebagai alat penyelidikan.

2. Kekurangan Observasi

Beberapa kekurangan metode observasi, yaitu:

- Pengamat membutuhkan waktu untuk menunggu tindakan tertentu.

- Terdapat beberapa data yang tidak bisa dilakukan dengan observasi, misalnya rahasia pribadi seseorang.

- Kecenderungan seseorang yang sedang diobservasi untuk berperilaku atau bersikap sesuai dengan yang diharapkan pengamat.

Rekomendasi Buku & Artikel Terkait

Buku terkait sejarah indonesia.

- Buku Ensiklopedia

- Buku Geografi

- Buku Obat Tradisional

- Buku Sastra Indonesia

- Buku Sejarah Indonesia

- Buku Sejarah & Peradaban Agama Islam

- Buku Sosiologi

Materi Terkait Sejarah Indonesia

- Analisis Komparatif

- Cara Membuat Abstrak

- Cara Menentukan Judul Skripsi

- Contoh Kata Pengantar Skripsi

- Contoh Kata Pengantar Karya Ilmiah

- Ciri-Ciri Teks Laporan Hasil Observasi

- Contoh Teks Laporan Hasil Observasi

- Cara Review Jurnal

- Hipotesis Komparatif

- Identifikasi Masalah

- Pengertian Identifikasi

- Karya Ilmiah Populer

- Langkah Mempersiapkan Wawancara

- Contoh Outline Skripsi

- Laporan Teks Percobaan

- Metode Komparatif

- Notasi Ilmiah

- Objek Penelitian

- Penelitian Deskriptif

- Pendekatan Holistik

- Pendekatan Kelingkungan

- Penelitian Komparatif

- Pendekatan Konstruktivisme

- Pendekatan Kuantitatif

- Perbedaan Artikel dan Jurnal

- Studi Kasus

- Studi Komparatif

- Studi Pustaka

- Uji Asumsi Klasik

- Variabel Penelitian

ePerpus adalah layanan perpustakaan digital masa kini yang mengusung konsep B2B. Kami hadir untuk memudahkan dalam mengelola perpustakaan digital Anda. Klien B2B Perpustakaan digital kami meliputi sekolah, universitas, korporat, sampai tempat ibadah."

- Akses ke ribuan buku dari penerbit berkualitas

- Kemudahan dalam mengakses dan mengontrol perpustakaan Anda

- Tersedia dalam platform Android dan IOS

- Tersedia fitur admin dashboard untuk melihat laporan analisis

- Laporan statistik lengkap

- Aplikasi aman, praktis, dan efisien

You may also like

Pendekatan Kuantitatif: Kunci Mengungkap Pola dan Tren...

Contoh Review Jurnal berikut dengan Strukturnya yang...

Studi Komparatif: Pengertian, Manfaat, Variabel, Macam...

Hipotesis Komparatif: Pengertian, Ciri, Langkah dan...

Memahami Analisis Komparatif: Langkah-Langkah...

Mengupas Penelitian Komparatif: Pengertian dan Metode...

About the author.

- Home | Vocasia

- Video dan Fotografi

- Akuntansi dan Keuangan

- Produktivitas Kantor

- Hobi dan Gaya Hidup

- Personal Development

- Free Webinar IPO

- Free Webinar Python

Metode Observasi dalam Penelitian Kualitatif, Beserta Penjelasannya

Dalam penelitian kualitatif, tentu diperlukan yang namanya pengumpulan data untuk menyusun sebuah laporan penelitian. Berdasarkan manfaat empiris, bahwa metode pengumpulan data kualitatif yang paling independen. Terhadap semua metode pengumpulan data, dan teknik analisis data. Salah satunya adalah metode observasi. Menurut sumber buku Penelitian Kualitatif edisi ke-2 (2007). Berikut adalah penjelasan mengenai metode observasi dalam penelitian kualitatif. Simak dibawah ini, ya!

Baca Juga : Metode Wawancara dalam Penelitian Kualitatif, Beserta Penjelasannya

Metode Observasi dalam Penelitian Kualitatif

Beberapa bentuk observasi yang dapat digunakan dalam penelitian kualitatif adalah sebagai berikut.

1. Observasi Partisipasi (Participant Observer)

Definisi observasi atau pengamatan adalah kegiatan keseharian manusia dengan menggunakan panca indra mata sebagai alat bantu utamanya. Lainnya seperti telinga, penciuman, mulut, dan kulit. Karena itu, observasi adalah kemampuan seseorang untuk menggunakan pengamatannya. Melalui hasil kerja panca indra mata serta dibantu dengan panca indra lainnya. Di dalam pembahasan ini kata observasi dan pengamatan digunakan secara bergantian. Seseorang yang sedang melakukan pengamatan tidak selamanya menggunakan apa yang terlihat di mata saja. Tetapi selalu mengaitkan apa yang dilihatnya dengan apa yang dihasilkan oleh anggota tubuh lainnya. Seperti apa yang ia dengar, apa yang ia cicipi, apa yang ia cium dari penciumannya. Bahkan dari apa yang ia rasakan dari sentuhan-sentuhan kulitnya.

Dari pemahaman observasi atau pengamatan di atas. Sesungguhnya yang dimaksud dengan metode observasi. Adalah metode pengumpulan data yang digunakan untuk menghimpun data penelitian melalui pengamatan dan pengindraan. Suatu kegiatan pengamatan baru dikategorikan sebagai kegiatan pengumpulan data penelitian. Apabila memiliki kriteria sebagai berikut:

- Pertama, pengamatan digunakan dalam penelitian dan telah direncanakan secara serius.

- Kedua, pengamatan harus berkaitan dengan tujuan penelitian yang telah ditetapkan.

- Ketiga, pengamatan dicatat secara sistematik dan dihubungkan dengan proposisi. Bukan dipaparkan sebagai suatu yang hanya menarik perhatian.

- Keempat, pengamatan dapat di cek dan dikontrol mengenai keabsahannya.

2. Observasi Tidak Berstruktur

Maksud dari observasi tidak berstruktur, yaitu observasi dilakukan tanpa menggunakan guide observasi . Dengan demikian, pada observasi ini pengamat harus mampu secara pribadi mengembangkan daya pengamatannya, dalam mengamati suatu objek. Pada observasi ini, yang terpenting adalah pengamat harus menguasai “ilmu” tentang objek secara umum. Dari apa yang hendak diamati, hal mana yang membedakannya dengan observasi partisipasi. Yaitu pengamat tidak perlu memahami secara teoritis terlebih dahulu objek penelitian. Dengan demikian, akan membantu lebih banyak pekerjaannya dalam mengamati objek yang baru itu.

3. Observasi Kelompok

Bentuk observasi lain yang sering digunakan pula adalah observasi kelompok. Biasanya observasi ini dilakukan secara berkelompok terhadap suatu atau beberapa objek sekaligus. Misalnya, suatu tim peneliti yang sedang mengamati gejolak perubahan harga pasar. Akibat kenaikan BBM biasanya bekerja dengan mengamati sekian banyak gejala lain. Dalam hal ini, yang berpengaruh terhadap perubahan harga pasar tersebut.

Hal-hal yang perlu diperhatikan dalam melakukan Observasi

Beberapa hal yang perlu diperhatikan dalam melakukan pengamatan, yaitu:

- Hal-hal apa yang hendak diamati,

- Bagaimana mencatat pengamatan,

- Alat bantu pengamatan,

- Bagaimana mengatur jarak antara pengamat dan objek yang diamati.

Kemudian hal-hal tersebut di atas hendaknya dipertimbangkan sebelum seseorang melakukan observasi. Karena hal-hal tersebut di atas amat menentukan berhasil tidaknya pengamat melakukan tugasnya.

Nah, itu tadi penjelasan mengenai metode observasi dalam penelitian kualitatif. Semoga artikel ini bermanfaat, jangan lupa cek postingan artikel yang lainnya juga, ya!

Baca juga : Perbandingan Desain Penelitian Kualitatif Burhan Bungin dan Craswell

Related Articles

15 Jurusan Kuliah Yang Menjanjikan Gaji Tinggi Untuk Wanita

Cara Menulis Footnote Dari Jurnal Dan Contohnya

17 Jurusan Kuliah Yang Tidak Ada Matematika, Apa Saja Ya?

23 Jurusan Ini Sedikit Peminat Tapi Peluang Kerja Besar Lho!

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Postingan Terbaru

Guest Relation Officer (GRO): Tugas, Skill, Kualifikasi dan Gajinya

Sales Associate: Tugas, Skill, Kualifikasi Hingga Gajinya

Admin Clerk: Tugas, Skill, Kualifikasi dan Gajinya

Apa itu bahasa pemrograman c++ ini penjelasan lengkapnya.

27 Ide Konten Tiktok Yang Menarik Agar FYP

5 komponen agility untuk menangkan persaingan bagi karyawan dan perusahaan.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Non-Experimental Research

32 Observational Research

Learning objectives.

- List the various types of observational research methods and distinguish between each.

- Describe the strengths and weakness of each observational research method.

What Is Observational Research?

The term observational research is used to refer to several different types of non-experimental studies in which behavior is systematically observed and recorded. The goal of observational research is to describe a variable or set of variables. More generally, the goal is to obtain a snapshot of specific characteristics of an individual, group, or setting. As described previously, observational research is non-experimental because nothing is manipulated or controlled, and as such we cannot arrive at causal conclusions using this approach. The data that are collected in observational research studies are often qualitative in nature but they may also be quantitative or both (mixed-methods). There are several different types of observational methods that will be described below.

Naturalistic Observation

Naturalistic observation is an observational method that involves observing people’s behavior in the environment in which it typically occurs. Thus naturalistic observation is a type of field research (as opposed to a type of laboratory research). Jane Goodall’s famous research on chimpanzees is a classic example of naturalistic observation. Dr. Goodall spent three decades observing chimpanzees in their natural environment in East Africa. She examined such things as chimpanzee’s social structure, mating patterns, gender roles, family structure, and care of offspring by observing them in the wild. However, naturalistic observation could more simply involve observing shoppers in a grocery store, children on a school playground, or psychiatric inpatients in their wards. Researchers engaged in naturalistic observation usually make their observations as unobtrusively as possible so that participants are not aware that they are being studied. Such an approach is called disguised naturalistic observation . Ethically, this method is considered to be acceptable if the participants remain anonymous and the behavior occurs in a public setting where people would not normally have an expectation of privacy. Grocery shoppers putting items into their shopping carts, for example, are engaged in public behavior that is easily observable by store employees and other shoppers. For this reason, most researchers would consider it ethically acceptable to observe them for a study. On the other hand, one of the arguments against the ethicality of the naturalistic observation of “bathroom behavior” discussed earlier in the book is that people have a reasonable expectation of privacy even in a public restroom and that this expectation was violated.

In cases where it is not ethical or practical to conduct disguised naturalistic observation, researchers can conduct undisguised naturalistic observation where the participants are made aware of the researcher presence and monitoring of their behavior. However, one concern with undisguised naturalistic observation is reactivity. Reactivity refers to when a measure changes participants’ behavior. In the case of undisguised naturalistic observation, the concern with reactivity is that when people know they are being observed and studied, they may act differently than they normally would. This type of reactivity is known as the Hawthorne effect . For instance, you may act much differently in a bar if you know that someone is observing you and recording your behaviors and this would invalidate the study. So disguised observation is less reactive and therefore can have higher validity because people are not aware that their behaviors are being observed and recorded. However, we now know that people often become used to being observed and with time they begin to behave naturally in the researcher’s presence. In other words, over time people habituate to being observed. Think about reality shows like Big Brother or Survivor where people are constantly being observed and recorded. While they may be on their best behavior at first, in a fairly short amount of time they are flirting, having sex, wearing next to nothing, screaming at each other, and occasionally behaving in ways that are embarrassing.

Participant Observation

Another approach to data collection in observational research is participant observation. In participant observation , researchers become active participants in the group or situation they are studying. Participant observation is very similar to naturalistic observation in that it involves observing people’s behavior in the environment in which it typically occurs. As with naturalistic observation, the data that are collected can include interviews (usually unstructured), notes based on their observations and interactions, documents, photographs, and other artifacts. The only difference between naturalistic observation and participant observation is that researchers engaged in participant observation become active members of the group or situations they are studying. The basic rationale for participant observation is that there may be important information that is only accessible to, or can be interpreted only by, someone who is an active participant in the group or situation. Like naturalistic observation, participant observation can be either disguised or undisguised. In disguised participant observation , the researchers pretend to be members of the social group they are observing and conceal their true identity as researchers.

In a famous example of disguised participant observation, Leon Festinger and his colleagues infiltrated a doomsday cult known as the Seekers, whose members believed that the apocalypse would occur on December 21, 1954. Interested in studying how members of the group would cope psychologically when the prophecy inevitably failed, they carefully recorded the events and reactions of the cult members in the days before and after the supposed end of the world. Unsurprisingly, the cult members did not give up their belief but instead convinced themselves that it was their faith and efforts that saved the world from destruction. Festinger and his colleagues later published a book about this experience, which they used to illustrate the theory of cognitive dissonance (Festinger, Riecken, & Schachter, 1956) [1] .

In contrast with undisguised participant observation , the researchers become a part of the group they are studying and they disclose their true identity as researchers to the group under investigation. Once again there are important ethical issues to consider with disguised participant observation. First no informed consent can be obtained and second deception is being used. The researcher is deceiving the participants by intentionally withholding information about their motivations for being a part of the social group they are studying. But sometimes disguised participation is the only way to access a protective group (like a cult). Further, disguised participant observation is less prone to reactivity than undisguised participant observation.

Rosenhan’s study (1973) [2] of the experience of people in a psychiatric ward would be considered disguised participant observation because Rosenhan and his pseudopatients were admitted into psychiatric hospitals on the pretense of being patients so that they could observe the way that psychiatric patients are treated by staff. The staff and other patients were unaware of their true identities as researchers.

Another example of participant observation comes from a study by sociologist Amy Wilkins on a university-based religious organization that emphasized how happy its members were (Wilkins, 2008) [3] . Wilkins spent 12 months attending and participating in the group’s meetings and social events, and she interviewed several group members. In her study, Wilkins identified several ways in which the group “enforced” happiness—for example, by continually talking about happiness, discouraging the expression of negative emotions, and using happiness as a way to distinguish themselves from other groups.

One of the primary benefits of participant observation is that the researchers are in a much better position to understand the viewpoint and experiences of the people they are studying when they are a part of the social group. The primary limitation with this approach is that the mere presence of the observer could affect the behavior of the people being observed. While this is also a concern with naturalistic observation, additional concerns arise when researchers become active members of the social group they are studying because that they may change the social dynamics and/or influence the behavior of the people they are studying. Similarly, if the researcher acts as a participant observer there can be concerns with biases resulting from developing relationships with the participants. Concretely, the researcher may become less objective resulting in more experimenter bias.

Structured Observation

Another observational method is structured observation . Here the investigator makes careful observations of one or more specific behaviors in a particular setting that is more structured than the settings used in naturalistic or participant observation. Often the setting in which the observations are made is not the natural setting. Instead, the researcher may observe people in the laboratory environment. Alternatively, the researcher may observe people in a natural setting (like a classroom setting) that they have structured some way, for instance by introducing some specific task participants are to engage in or by introducing a specific social situation or manipulation.

Structured observation is very similar to naturalistic observation and participant observation in that in all three cases researchers are observing naturally occurring behavior; however, the emphasis in structured observation is on gathering quantitative rather than qualitative data. Researchers using this approach are interested in a limited set of behaviors. This allows them to quantify the behaviors they are observing. In other words, structured observation is less global than naturalistic or participant observation because the researcher engaged in structured observations is interested in a small number of specific behaviors. Therefore, rather than recording everything that happens, the researcher only focuses on very specific behaviors of interest.

Researchers Robert Levine and Ara Norenzayan used structured observation to study differences in the “pace of life” across countries (Levine & Norenzayan, 1999) [4] . One of their measures involved observing pedestrians in a large city to see how long it took them to walk 60 feet. They found that people in some countries walked reliably faster than people in other countries. For example, people in Canada and Sweden covered 60 feet in just under 13 seconds on average, while people in Brazil and Romania took close to 17 seconds. When structured observation takes place in the complex and even chaotic “real world,” the questions of when, where, and under what conditions the observations will be made, and who exactly will be observed are important to consider. Levine and Norenzayan described their sampling process as follows:

“Male and female walking speed over a distance of 60 feet was measured in at least two locations in main downtown areas in each city. Measurements were taken during main business hours on clear summer days. All locations were flat, unobstructed, had broad sidewalks, and were sufficiently uncrowded to allow pedestrians to move at potentially maximum speeds. To control for the effects of socializing, only pedestrians walking alone were used. Children, individuals with obvious physical handicaps, and window-shoppers were not timed. Thirty-five men and 35 women were timed in most cities.” (p. 186).

Precise specification of the sampling process in this way makes data collection manageable for the observers, and it also provides some control over important extraneous variables. For example, by making their observations on clear summer days in all countries, Levine and Norenzayan controlled for effects of the weather on people’s walking speeds. In Levine and Norenzayan’s study, measurement was relatively straightforward. They simply measured out a 60-foot distance along a city sidewalk and then used a stopwatch to time participants as they walked over that distance.

As another example, researchers Robert Kraut and Robert Johnston wanted to study bowlers’ reactions to their shots, both when they were facing the pins and then when they turned toward their companions (Kraut & Johnston, 1979) [5] . But what “reactions” should they observe? Based on previous research and their own pilot testing, Kraut and Johnston created a list of reactions that included “closed smile,” “open smile,” “laugh,” “neutral face,” “look down,” “look away,” and “face cover” (covering one’s face with one’s hands). The observers committed this list to memory and then practiced by coding the reactions of bowlers who had been videotaped. During the actual study, the observers spoke into an audio recorder, describing the reactions they observed. Among the most interesting results of this study was that bowlers rarely smiled while they still faced the pins. They were much more likely to smile after they turned toward their companions, suggesting that smiling is not purely an expression of happiness but also a form of social communication.

In yet another example (this one in a laboratory environment), Dov Cohen and his colleagues had observers rate the emotional reactions of participants who had just been deliberately bumped and insulted by a confederate after they dropped off a completed questionnaire at the end of a hallway. The confederate was posing as someone who worked in the same building and who was frustrated by having to close a file drawer twice in order to permit the participants to walk past them (first to drop off the questionnaire at the end of the hallway and once again on their way back to the room where they believed the study they signed up for was taking place). The two observers were positioned at different ends of the hallway so that they could read the participants’ body language and hear anything they might say. Interestingly, the researchers hypothesized that participants from the southern United States, which is one of several places in the world that has a “culture of honor,” would react with more aggression than participants from the northern United States, a prediction that was in fact supported by the observational data (Cohen, Nisbett, Bowdle, & Schwarz, 1996) [6] .

When the observations require a judgment on the part of the observers—as in the studies by Kraut and Johnston and Cohen and his colleagues—a process referred to as coding is typically required . Coding generally requires clearly defining a set of target behaviors. The observers then categorize participants individually in terms of which behavior they have engaged in and the number of times they engaged in each behavior. The observers might even record the duration of each behavior. The target behaviors must be defined in such a way that guides different observers to code them in the same way. This difficulty with coding illustrates the issue of interrater reliability, as mentioned in Chapter 4. Researchers are expected to demonstrate the interrater reliability of their coding procedure by having multiple raters code the same behaviors independently and then showing that the different observers are in close agreement. Kraut and Johnston, for example, video recorded a subset of their participants’ reactions and had two observers independently code them. The two observers showed that they agreed on the reactions that were exhibited 97% of the time, indicating good interrater reliability.

One of the primary benefits of structured observation is that it is far more efficient than naturalistic and participant observation. Since the researchers are focused on specific behaviors this reduces time and expense. Also, often times the environment is structured to encourage the behaviors of interest which again means that researchers do not have to invest as much time in waiting for the behaviors of interest to naturally occur. Finally, researchers using this approach can clearly exert greater control over the environment. However, when researchers exert more control over the environment it may make the environment less natural which decreases external validity. It is less clear for instance whether structured observations made in a laboratory environment will generalize to a real world environment. Furthermore, since researchers engaged in structured observation are often not disguised there may be more concerns with reactivity.

Case Studies

A case study is an in-depth examination of an individual. Sometimes case studies are also completed on social units (e.g., a cult) and events (e.g., a natural disaster). Most commonly in psychology, however, case studies provide a detailed description and analysis of an individual. Often the individual has a rare or unusual condition or disorder or has damage to a specific region of the brain.

Like many observational research methods, case studies tend to be more qualitative in nature. Case study methods involve an in-depth, and often a longitudinal examination of an individual. Depending on the focus of the case study, individuals may or may not be observed in their natural setting. If the natural setting is not what is of interest, then the individual may be brought into a therapist’s office or a researcher’s lab for study. Also, the bulk of the case study report will focus on in-depth descriptions of the person rather than on statistical analyses. With that said some quantitative data may also be included in the write-up of a case study. For instance, an individual’s depression score may be compared to normative scores or their score before and after treatment may be compared. As with other qualitative methods, a variety of different methods and tools can be used to collect information on the case. For instance, interviews, naturalistic observation, structured observation, psychological testing (e.g., IQ test), and/or physiological measurements (e.g., brain scans) may be used to collect information on the individual.

HM is one of the most notorious case studies in psychology. HM suffered from intractable and very severe epilepsy. A surgeon localized HM’s epilepsy to his medial temporal lobe and in 1953 he removed large sections of his hippocampus in an attempt to stop the seizures. The treatment was a success, in that it resolved his epilepsy and his IQ and personality were unaffected. However, the doctors soon realized that HM exhibited a strange form of amnesia, called anterograde amnesia. HM was able to carry out a conversation and he could remember short strings of letters, digits, and words. Basically, his short term memory was preserved. However, HM could not commit new events to memory. He lost the ability to transfer information from his short-term memory to his long term memory, something memory researchers call consolidation. So while he could carry on a conversation with someone, he would completely forget the conversation after it ended. This was an extremely important case study for memory researchers because it suggested that there’s a dissociation between short-term memory and long-term memory, it suggested that these were two different abilities sub-served by different areas of the brain. It also suggested that the temporal lobes are particularly important for consolidating new information (i.e., for transferring information from short-term memory to long-term memory).

The history of psychology is filled with influential cases studies, such as Sigmund Freud’s description of “Anna O.” (see Note 6.1 “The Case of “Anna O.””) and John Watson and Rosalie Rayner’s description of Little Albert (Watson & Rayner, 1920) [7] , who allegedly learned to fear a white rat—along with other furry objects—when the researchers repeatedly made a loud noise every time the rat approached him.

The Case of “Anna O.”

Sigmund Freud used the case of a young woman he called “Anna O.” to illustrate many principles of his theory of psychoanalysis (Freud, 1961) [8] . (Her real name was Bertha Pappenheim, and she was an early feminist who went on to make important contributions to the field of social work.) Anna had come to Freud’s colleague Josef Breuer around 1880 with a variety of odd physical and psychological symptoms. One of them was that for several weeks she was unable to drink any fluids. According to Freud,

She would take up the glass of water that she longed for, but as soon as it touched her lips she would push it away like someone suffering from hydrophobia.…She lived only on fruit, such as melons, etc., so as to lessen her tormenting thirst. (p. 9)

But according to Freud, a breakthrough came one day while Anna was under hypnosis.

[S]he grumbled about her English “lady-companion,” whom she did not care for, and went on to describe, with every sign of disgust, how she had once gone into this lady’s room and how her little dog—horrid creature!—had drunk out of a glass there. The patient had said nothing, as she had wanted to be polite. After giving further energetic expression to the anger she had held back, she asked for something to drink, drank a large quantity of water without any difficulty, and awoke from her hypnosis with the glass at her lips; and thereupon the disturbance vanished, never to return. (p.9)

Freud’s interpretation was that Anna had repressed the memory of this incident along with the emotion that it triggered and that this was what had caused her inability to drink. Furthermore, he believed that her recollection of the incident, along with her expression of the emotion she had repressed, caused the symptom to go away.

As an illustration of Freud’s theory, the case study of Anna O. is quite effective. As evidence for the theory, however, it is essentially worthless. The description provides no way of knowing whether Anna had really repressed the memory of the dog drinking from the glass, whether this repression had caused her inability to drink, or whether recalling this “trauma” relieved the symptom. It is also unclear from this case study how typical or atypical Anna’s experience was.

Case studies are useful because they provide a level of detailed analysis not found in many other research methods and greater insights may be gained from this more detailed analysis. As a result of the case study, the researcher may gain a sharpened understanding of what might become important to look at more extensively in future more controlled research. Case studies are also often the only way to study rare conditions because it may be impossible to find a large enough sample of individuals with the condition to use quantitative methods. Although at first glance a case study of a rare individual might seem to tell us little about ourselves, they often do provide insights into normal behavior. The case of HM provided important insights into the role of the hippocampus in memory consolidation.

However, it is important to note that while case studies can provide insights into certain areas and variables to study, and can be useful in helping develop theories, they should never be used as evidence for theories. In other words, case studies can be used as inspiration to formulate theories and hypotheses, but those hypotheses and theories then need to be formally tested using more rigorous quantitative methods. The reason case studies shouldn’t be used to provide support for theories is that they suffer from problems with both internal and external validity. Case studies lack the proper controls that true experiments contain. As such, they suffer from problems with internal validity, so they cannot be used to determine causation. For instance, during HM’s surgery, the surgeon may have accidentally lesioned another area of HM’s brain (a possibility suggested by the dissection of HM’s brain following his death) and that lesion may have contributed to his inability to consolidate new information. The fact is, with case studies we cannot rule out these sorts of alternative explanations. So, as with all observational methods, case studies do not permit determination of causation. In addition, because case studies are often of a single individual, and typically an abnormal individual, researchers cannot generalize their conclusions to other individuals. Recall that with most research designs there is a trade-off between internal and external validity. With case studies, however, there are problems with both internal validity and external validity. So there are limits both to the ability to determine causation and to generalize the results. A final limitation of case studies is that ample opportunity exists for the theoretical biases of the researcher to color or bias the case description. Indeed, there have been accusations that the woman who studied HM destroyed a lot of her data that were not published and she has been called into question for destroying contradictory data that didn’t support her theory about how memories are consolidated. There is a fascinating New York Times article that describes some of the controversies that ensued after HM’s death and analysis of his brain that can be found at: https://www.nytimes.com/2016/08/07/magazine/the-brain-that-couldnt-remember.html?_r=0

Archival Research

Another approach that is often considered observational research involves analyzing archival data that have already been collected for some other purpose. An example is a study by Brett Pelham and his colleagues on “implicit egotism”—the tendency for people to prefer people, places, and things that are similar to themselves (Pelham, Carvallo, & Jones, 2005) [9] . In one study, they examined Social Security records to show that women with the names Virginia, Georgia, Louise, and Florence were especially likely to have moved to the states of Virginia, Georgia, Louisiana, and Florida, respectively.

As with naturalistic observation, measurement can be more or less straightforward when working with archival data. For example, counting the number of people named Virginia who live in various states based on Social Security records is relatively straightforward. But consider a study by Christopher Peterson and his colleagues on the relationship between optimism and health using data that had been collected many years before for a study on adult development (Peterson, Seligman, & Vaillant, 1988) [10] . In the 1940s, healthy male college students had completed an open-ended questionnaire about difficult wartime experiences. In the late 1980s, Peterson and his colleagues reviewed the men’s questionnaire responses to obtain a measure of explanatory style—their habitual ways of explaining bad events that happen to them. More pessimistic people tend to blame themselves and expect long-term negative consequences that affect many aspects of their lives, while more optimistic people tend to blame outside forces and expect limited negative consequences. To obtain a measure of explanatory style for each participant, the researchers used a procedure in which all negative events mentioned in the questionnaire responses, and any causal explanations for them were identified and written on index cards. These were given to a separate group of raters who rated each explanation in terms of three separate dimensions of optimism-pessimism. These ratings were then averaged to produce an explanatory style score for each participant. The researchers then assessed the statistical relationship between the men’s explanatory style as undergraduate students and archival measures of their health at approximately 60 years of age. The primary result was that the more optimistic the men were as undergraduate students, the healthier they were as older men. Pearson’s r was +.25.

This method is an example of content analysis —a family of systematic approaches to measurement using complex archival data. Just as structured observation requires specifying the behaviors of interest and then noting them as they occur, content analysis requires specifying keywords, phrases, or ideas and then finding all occurrences of them in the data. These occurrences can then be counted, timed (e.g., the amount of time devoted to entertainment topics on the nightly news show), or analyzed in a variety of other ways.

Media Attributions

- What happens when you remove the hippocampus? – Sam Kean by TED-Ed licensed under a standard YouTube License

- Pappenheim 1882 by unknown is in the Public Domain .

- Festinger, L., Riecken, H., & Schachter, S. (1956). When prophecy fails: A social and psychological study of a modern group that predicted the destruction of the world. University of Minnesota Press. ↵

- Rosenhan, D. L. (1973). On being sane in insane places. Science, 179 , 250–258. ↵

- Wilkins, A. (2008). “Happier than Non-Christians”: Collective emotions and symbolic boundaries among evangelical Christians. Social Psychology Quarterly, 71 , 281–301. ↵

- Levine, R. V., & Norenzayan, A. (1999). The pace of life in 31 countries. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 30 , 178–205. ↵

- Kraut, R. E., & Johnston, R. E. (1979). Social and emotional messages of smiling: An ethological approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37 , 1539–1553. ↵

- Cohen, D., Nisbett, R. E., Bowdle, B. F., & Schwarz, N. (1996). Insult, aggression, and the southern culture of honor: An "experimental ethnography." Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70 (5), 945-960. ↵

- Watson, J. B., & Rayner, R. (1920). Conditioned emotional reactions. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 3 , 1–14. ↵

- Freud, S. (1961). Five lectures on psycho-analysis . New York, NY: Norton. ↵

- Pelham, B. W., Carvallo, M., & Jones, J. T. (2005). Implicit egotism. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14 , 106–110. ↵

- Peterson, C., Seligman, M. E. P., & Vaillant, G. E. (1988). Pessimistic explanatory style is a risk factor for physical illness: A thirty-five year longitudinal study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 55 , 23–27. ↵

Research that is non-experimental because it focuses on recording systemic observations of behavior in a natural or laboratory setting without manipulating anything.

An observational method that involves observing people’s behavior in the environment in which it typically occurs.

When researchers engage in naturalistic observation by making their observations as unobtrusively as possible so that participants are not aware that they are being studied.

Where the participants are made aware of the researcher presence and monitoring of their behavior.

Refers to when a measure changes participants’ behavior.

In the case of undisguised naturalistic observation, it is a type of reactivity when people know they are being observed and studied, they may act differently than they normally would.

Researchers become active participants in the group or situation they are studying.

Researchers pretend to be members of the social group they are observing and conceal their true identity as researchers.

Researchers become a part of the group they are studying and they disclose their true identity as researchers to the group under investigation.

When a researcher makes careful observations of one or more specific behaviors in a particular setting that is more structured than the settings used in naturalistic or participant observation.

A part of structured observation whereby the observers use a clearly defined set of guidelines to "code" behaviors—assigning specific behaviors they are observing to a category—and count the number of times or the duration that the behavior occurs.

An in-depth examination of an individual.

A family of systematic approaches to measurement using qualitative methods to analyze complex archival data.

Research Methods in Psychology Copyright © 2019 by Rajiv S. Jhangiani, I-Chant A. Chiang, Carrie Cuttler, & Dana C. Leighton is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Skip to secondary menu

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

Statistics By Jim

Making statistics intuitive

What is an Observational Study: Definition & Examples

By Jim Frost 10 Comments

What is an Observational Study?

An observational study uses sample data to find correlations in situations where the researchers do not control the treatment, or independent variable, that relates to the primary research question. The definition of an observational study hinges on the notion that the researchers only observe subjects and do not assign them to the control and treatment groups. That’s the key difference between an observational study vs experiment. These studies are also known as quasi-experiments and correlational studies .

True experiments assign subject to the experimental groups where the researchers can manipulate the conditions. Unfortunately, random assignment is not always possible. For these cases, you can conduct an observational study.

In this post, learn about the types of observational studies, why they are susceptible to confounding variables, and how they compare to experiments. I’ll close this post by reviewing a published observational study about vitamin supplement usage.

Observational Study Definition

In an observational study, the researchers only observe the subjects and do not interfere or try to influence the outcomes. In other words, the researchers do not control the treatments or assign subjects to experimental groups. Instead, they observe and measure variables of interest and look for relationships between them. Usually, researchers conduct observational studies when it is difficult, impossible, or unethical to assign study participants to the experimental groups randomly. If you can’t randomly assign subjects to the treatment and control groups, then you observe the subjects in their self-selected states.

Observational Study vs Experiment

Randomized experiments provide better results than observational studies. Consequently, you should always use a randomized experiment whenever possible. However, if randomization is not possible, science should not come to a halt. After all, we still want to learn things, discover relationships, and make discoveries. For these cases, observational studies are a good alternative to a true experiment. Let’s compare the differences between an observational study vs. an experiment.

Random assignment in an experiment reduces systematic differences between experimental groups at the beginning of the study, which increases your confidence that the treatments caused any differences between groups you observe at the end of the study. In contrast, an observational study uses self-formed groups that can have pre-existing differences, which introduces the problem of confounding variables. More on that later!

In a randomized experiment, randomization tends to equalize confounders between groups and, thereby, prevents problems. In my post about random assignment , I describe that process as an elegant solution for confounding variables. You don’t need to measure or even know which variables are confounders, and randomization will still mitigate their effects. Additionally, you can use control variables in an experiment to keep the conditions as consistent as possible. For more detail about the differences, read Observational Study vs. Experiment .

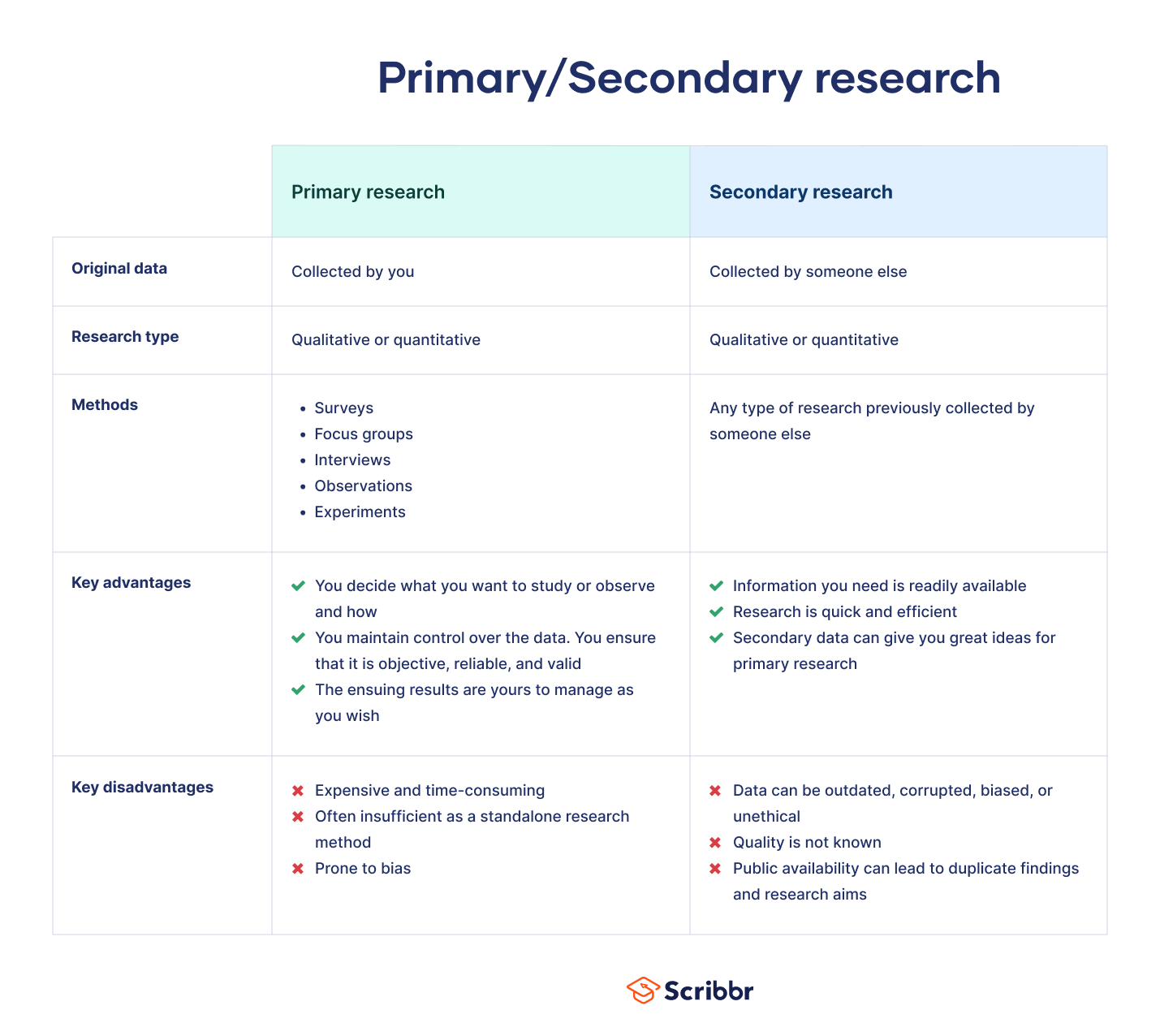

|

| |

| Does not assign subjects to groups | Randomly assigns subjects to control and treatment groups |

| Does not control variables that can affect outcome | Administers treatments and controls influence of other variables |

| Correlational findings. Differences might be due to confounders rather than the treatment | More confident that treatments cause the differences in outcomes |

If you’re looking for a middle ground choice between observational studies vs experiments, consider using a quasi-experimental design. These methods don’t require you to randomly assign participants to the experimental groups and still allow you to draw better causal conclusions about an intervention than an observational study. Learn more about Quasi-Experimental Design Overview & Examples .

Related posts : Experimental Design: Definition and Examples , Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) , and Control Groups in Experiments

Observational Study Examples

Consider using an observational study when random assignment for an experiment is problematic. This approach allows us to proceed and draw conclusions about effects even though we can’t control the independent variables. The following observational study examples will help you understand when and why to use them.

For example, if you’re studying how depression affects performance of an activity, it’s impossible to assign subjects to the depression and control group randomly. However, you can have subjects with and without depression perform the activity and compare the results in an observational study.

Or imagine trying to assign subjects to cigarette smoking and non-smoking groups randomly?! However, you can observe people in both groups and assess the differences in health outcomes in an observational study.

Suppose you’re studying a treatment for a disease. Ideally, you recruit a group of patients who all have the disease, and then randomly assign them to the treatment and control group. However, it’s unethical to withhold the treatment, which rules out a control group. Instead, you can compare patients who voluntarily do not use the medicine to those who do use it.

In all these observational study examples, the researchers do not assign subjects to the experimental groups. Instead, they observe people who are already in these groups and compare the outcomes. Hence, the scientists must use an observational study vs. an experiment.

Types of Observational Studies

The observational study definition states that researchers only observe the outcomes and do not manipulate or control factors . Despite this limitation, there various types of observational studies.

The following experimental designs are three standard types of observational studies.

- Cohort Study : A longitudinal observational study that follows a group who share a defining characteristic. These studies frequently determine whether exposure to risk factor affects an outcome over time.

- Case-Control Study : A retrospective observational study that compares two existing groups—the case group with the condition and the control group without it. Researchers compare the groups looking for potential risk factors for the condition.

- Cross-Sectional Study : Takes a snapshot of a moment in time so researchers can understand the prevalence of outcomes and correlations between variables at that instant.

Qualitative research studies are usually observational in nature, but they collect non-numeric data and do not perform statistical analyses.

Retrospective studies must be observational.

Later in this post, we’ll closely examine a quantitative observational study example that assesses vitamin supplement consumption and how that affects the risk of death. It’s possible to use random assignment to place each subject in either the vitamin treatment group or the control group. However, the study assesses vitamin consumption in 40,000 participants over the course of two decades. It’s unrealistic to enforce the treatment and control protocols over such a long time for so many people!

Drawbacks of Observational Studies

While observational studies get around the inability to assign subjects randomly, this approach opens the door to the problem of confounding variables. A confounding variable, or confounder, correlates with both the experimental groups and the outcome variable. Because there is no random process that equalizes the experimental groups in an observational study, confounding variables can systematically differ between groups when the study begins. Consequently, confounders can be the actual cause for differences in outcome at the end of the study rather than the primary variable of interest. If an experiment does not account for confounding variables, confounders can bias the results and create spurious correlations .

Performing an observational study can decrease the internal validity of your study but increase the external validity. Learn more about internal and external validity .

Let’s see how this works. Imagine an observational study that compares people who take vitamin supplements to those who do not. People who use vitamin supplements voluntarily will tend to have other healthy habits that exist at the beginning of the study. These healthy habits are confounding variables. If there are differences in health outcomes at the end of the study, it’s possible that these healthy habits actually caused them rather than the vitamin consumption itself. In short, confounders confuse the results because they provide alternative explanations for the differences.

Despite the limitations, an observational study can be a valid approach. However, you must ensure that your research accounts for confounding variables. Fortunately, there are several methods for doing just that!

Learn more about Correlation vs. Causation: Understanding the Differences .

Accounting for Confounding Variables in an Observational Study

Because observational studies don’t use random assignment, confounders can be distributed disproportionately between conditions. Consequently, experimenters need to know which variables are confounders, measure them, and then use a method to account for them. It involves more work, and the additional measurements can increase the costs. And there’s always a chance that researchers will fail to identify a confounder, not account for it, and produce biased results. However, if randomization isn’t an option, then you probably need to consider an observational study.

Trait matching and statistically controlling confounders using multivariate procedures are two standard approaches for incorporating confounding variables.

Related post : Causation versus Correlation in Statistics

Matching in Observational Studies

Matching is a technique that involves selecting study participants with similar characteristics outside the variable of interest or treatment. Rather than using random assignment to equalize the experimental groups, the experimenters do it by matching observable characteristics. For every participant in the treatment group, the researchers find a participant with comparable traits to include in the control group. Matching subjects facilitates valid comparisons between those groups. The researchers use subject-area knowledge to identify characteristics that are critical to match.

For example, a vitamin supplement study using matching will select subjects who have similar health-related habits and attributes. The goal is that vitamin consumption will be the primary difference between the groups, which helps you attribute differences in health outcomes to vitamin consumption. However, the researchers are still observing participants who decide whether they consume supplements.

Matching has some drawbacks. The experimenters might not be aware of all the relevant characteristics they need to match. In other words, the groups might be different in an essential aspect that the researchers don’t recognize. For example, in the hypothetical vitamin study, there might be a healthy habit or attribute that affects the outcome that the researchers don’t measure and match. These unmatched characteristics might cause the observed differences in outcomes rather than vitamin consumption.

Learn more about Matched Pairs Design: Uses & Examples .

Using Multiple Regression in Observational Studies

Random assignment and matching use different methods to equalize the experimental groups in an observational study. However, statistical techniques, such as multiple regression analysis , don’t try to equalize the groups but instead use a model that accounts for confounding variables. These studies statistically control for confounding variables.

In multiple regression analysis, including a variable in the model holds it constant while you vary the variable/treatment of interest. For information about this property, read my post When Should I Use Regression Analysis?

As with matching, the challenge is to identify, measure, and include all confounders in the regression model. Failure to include a confounding variable in a regression model can cause omitted variable bias to distort your results.

Next, we’ll look at a published observational study that uses multiple regression to account for confounding variables.

Related post : Independent and Dependent Variables in a Regression Model

Vitamin Supplement Observational Study Example

Murso et al. (2011)* use a longitudinal observational study that ran 22 years to assess differences in death rates for subjects who used vitamin supplements regularly compared to those who did not use them. This study used surveys to record the characteristics of approximately 40,000 participants. The surveys asked questions about potential confounding variables such as demographic information, food intake, health details, physical activity, and, of course, supplement intake.

Because this is an observational study, the subjects decided for themselves whether they were taking vitamin supplements. Consequently, it’s safe to assume that supplement users and non-users might be different in other ways. From their article, the researchers found the following pre-existing differences between the two groups:

Supplement users had a lower prevalence of diabetes mellitus, high blood pressure, and smoking status; a lower BMI and waist to hip ratio, and were less likely to live on a farm. Supplement users had a higher educational level, were more physically active and were more likely to use estrogen replacement therapy. Also, supplement users were more likely to have a lower intake of energy, total fat, and monounsaturated fatty acids, saturated fatty acids and to have a higher intake of protein, carbohydrates, polyunsaturated fatty acids, alcohol, whole grain products, fruits, and vegetables.

Whew! That’s a long list of differences! Supplement users were different from non-users in a multitude of ways that are likely to affect their risk of dying. The researchers must account for these confounding variables when they compare supplement users to non-users. If they do not, their results can be biased.

This example illustrates a key difference between an observational study vs experiment. In a randomized experiment, the randomization would have equalized the characteristics of those the researchers assigned to the treatment and control groups. Instead, the study works with self-sorted groups that have numerous pre-existing differences!

Using Multiple Regression to Statistically Control for Confounders

To account for these initial differences in the vitamin supplement observational study, the researchers use regression analysis and include the confounding variables in the model.

The researchers present three regression models. The simplest model accounts only for age and caloric intake. Next, are two models that include additional confounding variables beyond age and calories. The first model adds various demographic information and seven health measures. The second model includes everything in the previous model and adds several more specific dietary intake measures. Using statistical significance as a guide for specifying the correct regression model , the researchers present the model with the most variables as the basis for their final results.

It’s instructive to compare the raw results and the final regression results.

Raw results

The raw differences in death risks for consumers of folic acid, vitamin B6, magnesium, zinc, copper, and multivitamins are NOT statistically significant. However, the raw results show a significant reduction in the death risk for users of B complex, C, calcium, D, and E.

However, those are the raw results for the observational study, and they do not control for the long list of differences between the groups that exist at the beginning of the study. After using the regression model to control for the confounding variables statistically, the results change dramatically.

Adjusted results

Of the 15 supplements that the study tracked in the observational study, researchers found consuming seven of these supplements were linked to a statistically significant INCREASE in death risk ( p-value < 0.05): multivitamins (increase in death risk 2.4%), vitamin B6 (4.1%), iron (3.9%), folic acid (5.9%), zinc (3.0%), magnesium (3.6%), and copper (18.0%). Only calcium was associated with a statistically significant reduction in death risk of 3.8%.

In short, the raw results suggest that those who consume supplements either have the same or lower death risks than non-consumers. However, these results do not account for the multitude of healthier habits and attributes in the group that uses supplements.

In fact, these confounders seem to produce most of the apparent benefits in the raw results because, after you statistically control the effects of these confounding variables, the results worsen for those who consume vitamin supplements. The adjusted results indicate that most vitamin supplements actually increase your death risk!

This research illustrates the differences between an observational study vs experiment. Namely how the pre-existing differences between the groups allow confounders to bias the raw results, making the vitamin consumption outcomes look better than they really are.

In conclusion, if you can’t randomly assign subjects to the experimental groups, an observational study might be right for you. However, be aware that you’ll need to identify, measure, and account for confounding variables in your experimental design.

Jaakko Mursu, PhD; Kim Robien, PhD; Lisa J. Harnack, DrPH, MPH; Kyong Park, PhD; David R. Jacobs Jr, PhD; Dietary Supplements and Mortality Rate in Older Women: The Iowa Women’s Health Study ; Arch Intern Med . 2011;171(18):1625-1633.

Share this:

Reader Interactions

December 30, 2023 at 5:05 am

I see, but our professor required us to indicate what year it was put into the article. May you tell me what year was this published originally? <3

December 30, 2023 at 3:40 pm

December 29, 2023 at 10:46 am

Hi, may I use your article as a citation for my thesis paper? If so, may I know the exact date you published this article? Thank you!

December 29, 2023 at 2:13 pm

Definitely feel free to cite this article! 🙂

When citing online resources, you typically use an “Accessed” date rather than a publication date because online content can change over time. For more information, read Purdue University’s Citing Electronic Resources .

November 18, 2021 at 10:09 pm

Love your content and has been very helpful!

Can you please advise the question below using an observational data set:

I have three years of observational GPS data collected on athletes (2019/2020/2021). Approximately 14-15 athletes per game and 8 games per year. The GPS software outputs 50+ variables for each athlete in each game, which we have narrowed down to 16 variables of interest from previous research.

2 factors 1) Period (first half, second half, and whole game), 2) Position (two groups with three subgroups in each – forwards (group 1, group 2, group 3) and backs (group 1, group 2, group 3))

16 variables of interest – all numerical and scale variables. Some of these are correlated, but not all.

My understanding is that I can use a oneway ANOVA for each year on it’s own, using one factor at a time (period or position) with post hoc analysis. This is fine, if data meets assumptions and is normally distributed. This tells me any significant interactions between variables of interest with chosen factor. For example, with position factor, do forwards in group 1 cover more total running distance than forwards in group 2 or backs in group 3.

However, I want to go deeper with my analysis. If I want to see if forwards in group 1 cover more total running distance in period 1 than backs in group 3 in the same period, I need an additional factor and the oneway ANOVA does not suit. Therefore I can use a twoway ANOVA instead of 2 oneway ANOVA’s and that solves the issue, correct?

This is complicated further by looking to compare 2019 to 2020 or 2019 to 2021 to identify changes over time, which would introduce a third independent variable.

I believe this would require a threeway ANOVA for this observational data set. 3 factors – Position, Period, and Year?

Are there any issues or concerns you see at first glance?

I appreciate your time and consideration.

April 12, 2021 at 2:02 pm

Could an observational study use a correlational design.

e.g. measuring effects of two variables on happiness, if you’re not intervening.

April 13, 2021 at 12:14 am

Typically, with observational studies, you’d want to include potential confounders, etc. Consequently, I’ve seen regression analysis used more frequently for observational studies to be able to control for other things because you’re not using randomization. You could use correlation to observe the relationship. However, you wouldn’t be controlling for potential confounding variables. Just something to consider.

April 11, 2021 at 1:28 pm