- Open access

- Published: 27 March 2023

Internet use, users, and cognition: on the cognitive relationships between Internet-based technology and Internet users

- Vishruth M. Nagam 1

BMC Psychology volume 11 , Article number: 82 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

3175 Accesses

2 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

This study aims to investigate growing Internet use in relation to memory and cognition. Though literature reveals human capability to utilize the Internet as a transactive memory source, the formational mechanisms of such transactive memory systems are not extensively explored. The Internet’s comparative effects on transactive memory and semantic memory are also relatively unknown.

This study comprises two experimental memory task survey phases utilizing null hypothesis and standard error tests to assess significance of results.

When information is expected to be saved and accessible, recall rates are lower, regardless of explicit instructions to remember (Phase 1, N = 20). Phase 2 suggests the importance of order of attempted recall: depending on whether users first attempt to recall (1) desired information or (2) the information’s location, subsequent successful cognitive retrieval is more likely to occur for (1) only desired information or both desired information and location thereof or (2) only desired information’s location, respectively (N = 22).

Conclusions

This study yields several theoretical advances in memory research. The notion of information being saved online and accessible in the future negatively affects semantic memory. Phase 2 reveals an adaptive dynamic—(1) as Internet users often have a vague idea of desired information before searching for it on the Internet, first accessing semantic memory serves as an aid for subsequent transactive memory use and (2) if transactive memory access is successful, the need to retrieve desired information from semantic memory is inherently eliminated. By repeatedly defaulting to first accessing semantic memory and then transactive memory or to accessing transactive memory only, Internet users may form and reinforce transactive memory systems with the Internet, or may refrain from enhancing and decrease reliance on transactive memory systems by repeatedly defaulting to access only semantic memory; the formation and permanence of transactive memory systems are subject to users’ will. Future research spans the domains of psychology and philosophy.

Peer Review reports

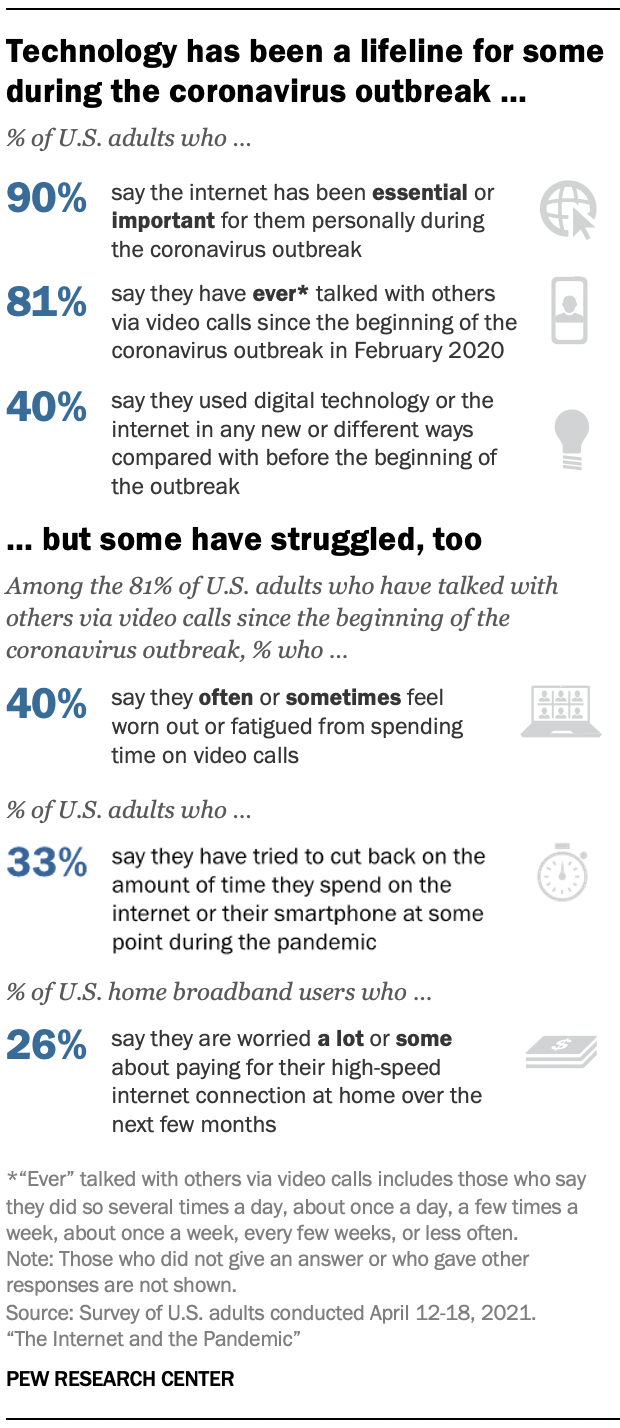

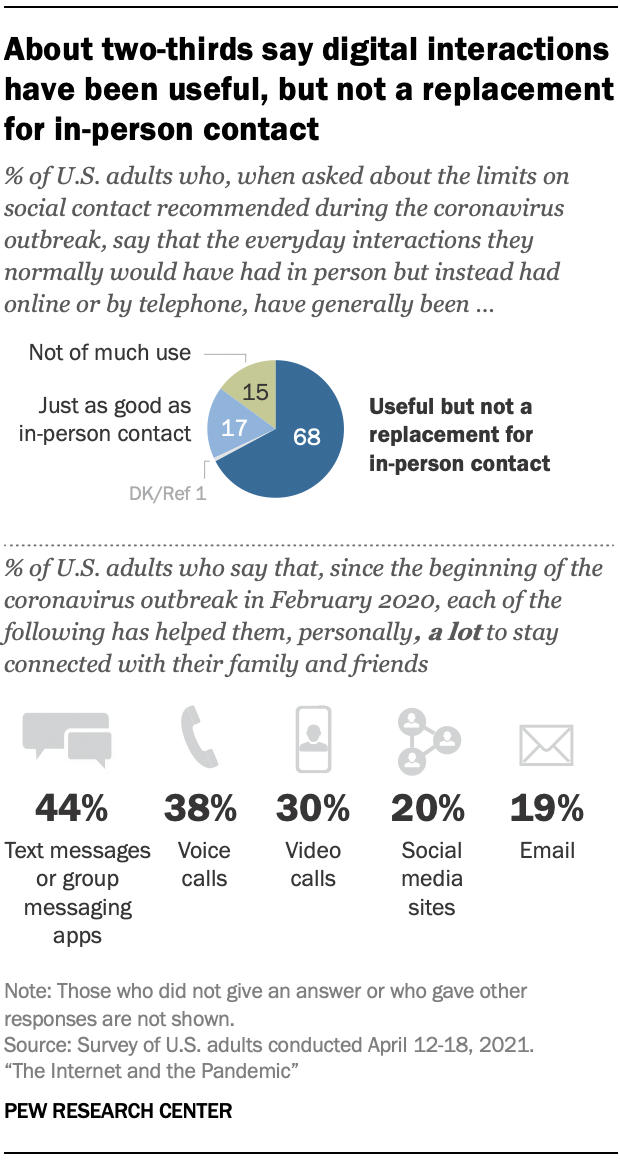

The Internet is a relatively recent invention, having been established in 1983, yet its reach has extended across the globe [ 1 ]. Over the past 2 decades, the world has seen a distinct increase in the number of people connected to the Internet (from 5 to 58.7%) [ 2 ]. Furthermore, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, many in-person activities have been shifted to virtual Internet-based mediums. The Internet has become a part of daily life for many individuals, and thus it is necessary to investigate the Internet’s potential cognitive implications.

“I don’t know; ‘Google’ it!” has become a common household remark in response to a question that cannot be answered at the moment. With the Internet being accessible through various means of technology, people often utilize search engines with complex algorithms to find any needed information. Regardless of whether people have to recall the precise quantities of ingredients in a recipe or how many points a basketball player scored in a game, they instantly search for it on the Internet using smart devices. People may experience withdrawal symptoms when they cannot instantly gratify themselves with the information they need, and thus some have even been led to believe that modern students, surrounded by various ways to access the Internet, are declining in intelligence and memory [ 3 ].

Throughout history and civilization, humans have relied on each other to share the burden of a cognitive task (e.g. remembering complex information), which has resulted in specialization in society and within relationships. Transactive memory refers to the idea that people develop a “system of encoding, storage, and retrieval of information from different knowledge domains.” This type of memory includes both the source of the information along with knowing the process of how to access or ask for that information when it is needed [ 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 ]. Thus, the “transactions” among individuals, as well as among the knowledge bases themselves, make up a transactive memory system.

In contrast, semantic memory is the long-term declarative memory of general facts and data. It consists of “cultural knowledge, ideas, and concepts” that have been accumulated throughout one’s lifetime [ 4 , 8 ]. Some examples of information falling under semantic memory may include the names of the most populous cities, the historical significance of a certain war, or basic multiplication and division rules. Though one may be able to store the same kind of information in working memory (i.e. short-term memory), the oft-ignored difference between working memory and semantic memory is that the latter allows for the long-term storage (more than a few seconds) of the information, which involves not only the hippocampus but also a vast network of cortical regions [ 4 ].

In previous studies, it has been determined that humans are capable of forming transactive memory systems, or collective storages of information outside of themselves, with the Internet [ 3 , 7 ]. However, the Internet’s effects on transactive memory in comparison to semantic memory have not been extensively explored; in addition, the mechanisms of how transactive memory systems with the Internet are established and strengthened are relatively unknown (see “ Hypothesis ” Section for further elaboration). This study investigates how the Internet plays a role in a transactive memory system with Internet users of the modern generation, the Internet’s comparative effects on transactive memory and semantic memory, and whether the cognitive implications of the aforementioned effects can help explain how transactive memory systems are formed and established. It was around these central aims that the hypothesis was framed.

The author’s hypothesis about human cognitive relationships with the Internet can be summarized in four parts to be tested in two experimental phases (Phases 1 and 2): (1) if it is expected that information will be saved and accessible in the future, people are less likely to recall the information (tested in Phase 1), (2) if it is expected that information will be saved in a known location, the memory of the location where the information is saved (transactive memory) is more enhanced than the memory of the information itself (semantic memory), as the location (e.g. a website name or a short folder name) may be more memorable (tested in Phase 2), (3) explicit instructions to remember do not have a significant effect on memory and recall (tested in Phase 1), and 4) if it is expected that information will be saved in a known location, the order of attempted recall may not have a significant effect on memory, if the memory questions are worded such that attempting to recall information does not influence attempts to recall the information’s location and vice versa (tested in Phase 2).

Hypothesis Parts 1, 2, and 3 are based on and serve to validate the findings of previous transactive memory research and theory and of the Internet’s known comparative effects on transactive memory and semantic memory [ 7 , 9 ]. In particular, Sparrow et al. show that transactive memory is enhanced in comparison to semantic memory, but only test access of transactive memory following prior access of semantic memory [ 9 ]. Thus, as an unexplored point of experimentation, Hypothesis Part 4 (testing order of attempted recall) was included in this study to potentially yield greater insight into the comparative effects of Internet use on transactive memory and semantic memory and into the formational mechanisms of transactive memory systems. Hypothesis Part 4 assumes the null hypothesis, as a sufficient base of evidence suggesting otherwise was not found.

Materials and methods

Twenty and twenty-two human volunteers participated in Phase 1 and Phase 2, respectively. All participants had a means of digitally accessing Google Forms (via Internet-connected devices). A stopwatch was used to ensure participants completed each step of the experiment in the allotted times. A calculator and spreadsheets software were used to perform data analysis.

Twenty-two students enrolled in Folsom Cordova Unified School District middle schools were administered the experimental memory task surveys. Parents and/or legal guardians of the students completed the Human Informed Consent Form, which contained brief information on the study. Phase 1 data was not available for two students.

All the participants first read thirty trivia-style statements on a Google Form (refer to Additional file 1 : Appendix B.1 for a digital copy). The participants were divided into two groups: half were told to remember the statements while the other half was not given any explicit memory instructions, in order to simulate attempting to recall information found on the Internet with and without anticipating that the information will be needed and/or tested in the future, respectively (refer to Additional file 1 :Appendix F for a participant flow diagram depicting how the hypothesis was addressed in the steps of Phase 1) [ 3 , 7 ].

Half of the statements were labeled as “Will Be Saved” and the other half as “Will Be Erased” on the Google Form. A ten-minute reading period was given for the participants to memorize the statements. By mentioning that only the “Will Be Saved” statements would be accessible later, the perception was created that the “Will Be Saved” statements would be available for future reference and that the “Will Be Erased” statements would not be accessible after the reading period (see Additional file 1 : Appendix B.3).

After the reading period, the participants were tested on their memory of the statements in an uncued recall format, which was chosen to prevent wording bias. The participants had ten minutes to type as many statements as they could remember into the Google Form (see Additional file 1 : Appendix B.2). Such quantification of memory of both groups of participants allows for an assessment of the first two parts of the hypothesis [ 7 ]. For example, to quantify the memory of saved statements (statements labeled as “Will Be Saved”) for the participants who were given explicit memory instructions, the calculation “(number of saved statements remembered by the participants with explicit memory instructions)/(total number of saved statements)” would be performed. The control in this experiment is the memory of the saved statements for the participants without any explicit memory instructions, as normally when using the Internet, people do not make conscious efforts to remember, and they know that the information they view is saved online, for instance, in a web page.

The purpose of explicitly telling only half of the participants to remember the statements and refraining from any memory instruction for the other half of the participants is to simulate attempts to remember online information when expecting or not expecting, respectively, the information will be needed and/or tested in the future. Thus, Phase 1 determines how the expectation of information being saved online and accessible in the future via Internet-based technology, as well as how being explicitly asked to remember, may influence semantic memory.

Phase 2 sought to determine if, with the expectation that the information will be saved in a known location, participants are more likely to remember where the information can be found (transactive memory) rather than the information itself (semantic memory). Phase 2 also investigates if the order of attempted recall (attempting to recall the information before its location, or vice versa) would have a significant effect on the participants’ memory (refer to Additional file 1 : Appendix F for a participant flow diagram depicting how the hypothesis was addressed in the steps of Phase 2).

Participants first read a list of thirty trivia-style statements (different from the list used in Phase 1) in random order on a Google Form (see Additional file 1 : Appendix D.1 for a digital copy). The statements were already randomly saved to one of four folders, all of which were similarly named (“Information,” “Facts,” “Points,” “Figures”), or saved in no specific folder (the phrases “generically saved” and “saved in no specific folder” will be used interchangeably in the rest of this paper). The trivia-style statements will be randomly distributed across the total five information storage locations, and each storage location would thus have six—an equal number of—statements. The purpose of generically saving a portion of the statements was to eliminate the effects of the added memory toll of having to remember a statement and its folder location [ 4 , 7 ]. A screenshot of all the folder locations in which these statements would be saved was given in the Google Form to ensure that the participants gained the perception that four-fifths of the statements are saved in their assigned folders and one-fifth of the statements are generically saved.

After a ten-minute reading period, participants were given another ten minutes to answer questions about all the statements and their folder locations phrased in a cued recall format on a Google Form (refer to Additional file 1 : Appendix D.2). The cued recall format was used to simulate Internet use, as, when people try to recall information, or the location thereof, that they know is saved on the Internet, they generally tend to have at least a vague idea of the information at hand [ 5 , 7 ]. In addition, the cued recall format for both semantic memory and transactive memory more accurately reflects real-world Internet use compared to previous Internet cognition studies, which only explore uncued recall with semantic memory and cued recall for transactive memory and thus exhibit implicit bias towards transactive memory [ 9 ]. Due to time constraints, the participants were tested on their memory of ten randomly selected statements and their folder locations (see Additional file 1 : Appendix D.3), yielding a total of twenty questions (ten statement questions and ten folder location questions).

The questions about the exact statements were free-response (answers with slightly different wordings that still convey the same meaning were accepted). For example, if the statement “A bolt of lightning contains enough energy to toast 100,000 slices of bread” was saved in the “Points” folder, a question about the statement might be structured like the following: “Enter the statement about lightning to the best of your ability.” The average proportion of statements remembered by each participant was calculated with the following expression: “(average number of correct statements / total number of statements tested)”. A question about a statement’s folder location might be structured like the following: “In which folder was the statement about lightning saved?” Each folder location question would require a short answer, such as “Figures” or “No specific folder.” In the case of the lightning question, the participant would have to type “Points” to correctly answer the question. The average proportion of folder locations remembered by each participant was calculated with the following expression: “(average number of correct folder locations / total number of folder location questions tested)”.

However, the average proportions of remembered statements and folder locations can be somewhat misleading, as a participant may have a higher chance of recalling the folder location of a statement due to the previous recalling of the statement or vice versa. To investigate further, on the Google Form, half of the folder location questions preceded the exact statement questions, and the other half of the folder location questions followed the exact statement questions. For example, for the lightning statement above, the folder location question follows the exact statement question, but for another statement, the folder location question may precede the exact statement question. This would help determine if order matters in recalling the statement and its folder location, simulating how the order of one’s attempted recall of information’s online location versus the information itself may influence transactive and/or semantic memory.

In addition, with just the average proportions of remembered statements and folder locations, an accurate conclusion cannot be made about the memory of a specific piece of information, as a participant may remember the statement but not its location or vice versa. To compare the participants’ memories of each statement and its folder location, the author calculated the proportions of statements for which the participants recalled (1) neither the statement nor folder location, (2) the folder location but not the statement, (3) the statement but not the folder location, and (4) both the statement and its folder location. These four cases were analyzed for both the group of statements that had the exact statement questions given first and the group of statements that had the folder location questions given first, resulting in eight total statistical cases. For example, to calculate the participants’ memory of case 2 statements (only folder location of those statements were remembered) that had the preceding folder location question, the expression “(number of case 2 statements with the preceding folder location question/total number of statements with the preceding folder location question)” was used. The control in this experiment would be the case 1 statements with the preceding statement question, as usually people tend to attempt recalling the saved information first before resorting to searching it on the Internet and because the memory of the case 1 statements would serve as a comparison to the statements in case 2, 3, and 4.

In this way, Phase 2 will help to conclude how the expectation that the desired information’s digital location affects memory of the information (semantic memory) in comparison to memory of the information’s location (transactive memory). Phase 2 will also help to determine if attempting to recall a statement or its folder location first affects the recall of the other.

Statistical analysis

Null hypothesis statistical tests were used to assess the statistical significance of the results of both Phases 1 and 2 to 95% confidence. One-tailed and two-tailed inferential t-tests were used depending on the nature of the hypothesis tested (e.g., as Hypothesis Part 1 poses significantly less recall when information is known to be saved, assessment of results pertaining to Hypothesis Part 1 warrants one-tailed statistical analyses. Assessments of Hypothesis Part 4 as the null hypothesis warrant two-tailed statistical analyses).

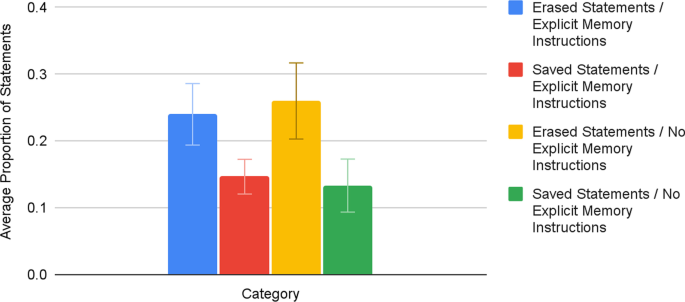

The analysis of the results of Phase 1 (refer to Fig. 1 ; see Additional file 1 : Appendix C for raw data), with Saved and Erased statement groups as well as explicit memory instructions and no memory instructions groups, showed that participants with explicit memory instructions (EMS) remembered the statements they believed to be erased (Erased/EMS M = 0.24, SE = 0.046) significantly better (t(14.235) = 1.775, p < 0.05, one-tailed unpooled t-test) than the statements they believed to be saved (Saved/EMS M = 0.147, SE = 0.026). Participants with no explicit memory instructions (NEMS) also remembered the Erased statements (Erased/NEMS M = 0.26, SE = 0.057) significantly better (t(16.016) = 1.81, p < 0.05, one-tailed unpooled t-test) than the Saved statements (Saved/NEMS M = 0.133, SE = 0.040). There were no significant differences in the memory of participants who received EMS and those who did not.

Proportion of “Will be Erased” and “Will be Saved” statements recalled, by the presence of explicit memory instructions.“Will be Erased” and “Will be Saved” statements are abbreviated as “Erased” and “Saved,” respectively. Error bars represent ± 1 SE X

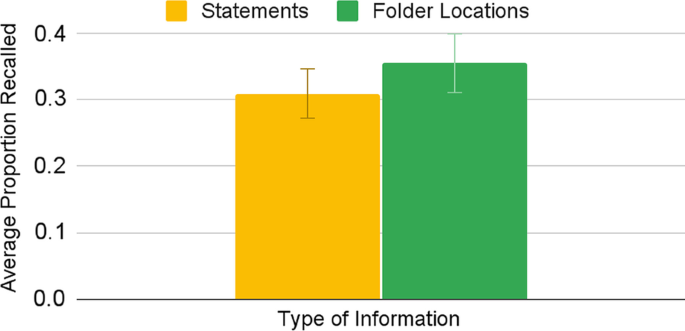

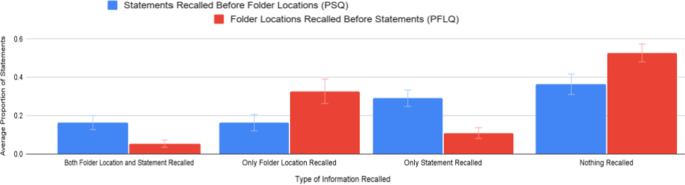

In Phase 2 (refer to Fig. 2 ), the participants correctly recalled on average 30.9% of the statements (SE = 0.037) and 35.4% of the folder locations (SE = 0.044); the difference between these values not being significant. Due to aforementioned reasons pertaining to the procedural steps of Phase 2 (refer to Procedural Steps for elaboration), the proportions of each of the four cases for the statements, both with the preceding statement question (PSQ) and the preceding folder location question (PFLQ), were calculated as well (refer to Fig. 3 ; see Additional file 1 : Appendix E for raw data).

Overall proportions of statements and folder locations recalled. Error bars represent ± 1 SE X

Proportion of statements and folder locations recalled, by order of recall and type of information recalled. Error bars represent ± 1 SE X

Participants were able to correctly recall both the statement and folder location (Both/PSQ M = 0.164, SE = 0.036) or only the folder location, but not the statement (Folder/PSQ M = 0.164, SE = 0.043) for relatively few statements with the PSQ. Participants were more likely to be able to recall only the statement, and not the folder location, (Statement/PSQ M = 0.291, SE = 0.043) or nothing at all (Nothing/PSQ M = 0.364, SE = 0.054) about the statements with the PSQ. The difference between the participants recalling only the statement and recalling only the folder location for the statements with the PSQ was significant (t(41.999) = − 2.090, p < 0.05, one-tailed unpooled t-test).

Participants were seldom able to recall both the statement and the folder location (Both/PFLQ M = 0.055, SE = 0.019) or only the statement, but not the folder location (Statement/PFLQ M = 0.109, SE = 0.029) for statements with the PFLQ. Participants were relatively more likely to be able to recall only the folder location, not the statement (Folder/PFLQ M = 0.327, SE = 0.064) or nothing at all (Nothing/PFLQ M = 0.527, SE = 0.047). The difference between the participants recalling only the folder location and recalling only the statement was significant (t(29.109) = − 3.121, p < 0.05, one-tailed unpooled t-test).

A comparison between the participants’ memory of the information about the statements with the PSQ and PFLQ is necessary to assess the fourth part of the hypothesis. Participants were significantly more likely to recall both the statement and the folder location (t(32.052) = 2.650, p < 0.05, two-tailed unpooled t-test), as well as only the statement and not the folder location (t(36.484) = 3.522, p < 0.05, two-tailed unpooled t-test), for statements with the PSQ than for the statements with the PFLQ. For statements with the PFLQ compared to statements with the PSQ, participants were significantly more likely to recall only the folder location, but not the statement (t(36.761) = -2.122, p < 0.05, two-tailed unpooled t-test), as well as nothing at all (t(41.199) = − 2.290, p < 0.05, two-tailed unpooled t-test).

The results from Phase 1 show that trivia statements believed to be erased were recalled significantly more than statements believed to be saved, regardless of the presence of explicit instructions to remember. People will not recall information they believe to be available to refer to later at the same rate as information believed to be erased; this may be due to the notion that they can look up any desired information using a search engine, thus eliminating the need to remember that piece of information. This result is similar to findings in directed forgetting studies, which have shown that people do not remember information they are told that they can forget as accurately as when they do expect the need to remember the information in the future [ 7 , 9 , 10 , 11 ]. Explicit memory instructions did not significantly influence memory; thus, it is reflected that the expectation of information being saved and later accessible affects recall rates more than the anticipation that the information will be needed and/or tested in the future. This finding may correspond to those in previous studies regarding comparisons between incidental and intentional learning of information, which have generally reported that explicit instructions to remember do not significantly influence memory of information [ 7 , 9 , 12 ]. Phase 1 thus supports Hypothesis Parts 1 and 3.

In Phase 2, there was not a significant difference between the overall recall rates of statements and folder locations. However, the analysis of the four cases of statements reveals that participants were more likely to recall both the statement and its folder location or only the statement, if the statement question preceded the folder location question. Conversely, if the folder location question preceded the statement question, participants were more likely to recall only the folder location or nothing at all. This novel finding reflects the dependence of people’s ability to recall information based on the order of attempted recall. Essentially, when people attempt to recall the “what” first, they are more likely to remember both the “what” and the “where” or only the “what;” when people attempt to recall the “where” first, they are more likely to remember only the “where” or nothing at all. Thus, the results of Phase 2 uphold Hypothesis Part 2 in certain cases (when transactive memory is accessed first), and disprove Hypothesis Part 4.

This study suggests that Internet-based technology may serve as a transactive memory source for the user, similar to how one could ask friends or colleagues to obtain any desired information. Semantic memory may be negatively impacted by the expectation that information will be saved and available for future reference, regardless of whether or not it is anticipated that the information will be needed or tested in the future (Phase 1). This study makes the novel proposition that the order of attempted recall (first attempting to recall the desired information versus its Internet location) affects Internet users’ rates of recall (Phase 2).

As an increasing proportion of our society plugs into the Internet, more and more users are forming interconnected transactive memory systems, not with each other, but with the Internet through various means of technology. Similar to how people remember to ask a friend in case they forget a homework assignment or to reach out to a colleague for the latest updates on a project, people are remembering the sorts of information the Internet holds and how to access it through our devices, rather than the information itself. Phases 1 and 2 together suggest that the common perception of the declining memory of society as a whole may be invalid, as we may simply be more frequently exercising a new type of memory—transactive memory rather than semantic memory [ 8 ]. Internet users are remembering more of how to navigate the Internet and focus on what they need to find, which may prove to be a useful skill in this age of modernization, when people are often bombarded with a constant influx of information from various online sources.

Phase 2 suggests, when transactive memory is accessed first, subsequent successful retrieval of information is more likely to occur from only transactive memory or not at all. A possible explanation for this phenomenon may lie in proactive interference, by which the activation of the memory system accessed first (transactive memory) disrupts the subsequent activation of and recall of information from another memory system (semantic memory), or an adaptive use of memory (see next paragraph for further elaboration). In addition, Phase 2 suggests that, when semantic memory is first accessed, subsequent successful retrieval of information may be enhanced for only semantic memory or both semantic memory and transactive memory. Thus, by repeatedly defaulting to first access semantic memory then transactive memory or first access only transactive memory, Internet users may build and strengthen transactive memory systems with the Internet—or, by defaulting to semantic memory without subsequently attempting to access transactive memory such that transactive memory is not activated, may refrain from enhancing and decrease reliance on transactive memory systems. This study proposes the novel observation that transactive memory systems with the Internet may be willingly formed and established, but not permanent (see “ Limitations and Future Directions ” Section).

It is also important to specifically note that when semantic memory is activated first, both semantic memory and transactive memory may be enhanced; however, if transactive memory is activated first, semantic memory is not enhanced. This novel finding may reflect an adaptive use of memory. As Internet users tend to have a vague idea of the online information desired before searching for it on the Internet, first attempting to recall the information itself from semantic memory may serve as an aid for subsequently recalling the information’s storage location from transactive memory (refer to Procedural Steps for a similar explanation of why cued recall was used). Conversely, if transactive memory and a transactive memory source are successfully first accessed, the need to access semantic memory for desired information is eliminated, as the desired information is now provided by the transactive memory source.

Limitations and future directions

Limitations are part of the experimental scientific process. As participants were garnered on a voluntary basis (see Additional file 1 : Appendix A for a digital copy of the Human Informed Consent Form), sampling bias may exist due to the possibility of the participants having stronger or weaker memory capacities than those of the majority of the human population of similar backgrounds. The sample size is not considered to be a limitation as the statistical analyses yielded significant findings assessing the fourfold hypothesis and leading to robust conclusions. Further research could study varying participant demographics, investigating how participant backgrounds may impact the formation and/or function of transactive memory systems.

In Phase 1, the participants were randomly split into two groups, with only one group receiving explicit memory instructions. There is a possibility that each of the groups as a whole may not have had similar memory capacities, which might have influenced the conclusion of the statistically insignificant effects of explicit memory instructions. Also, due to the memorable trivia-style nature of the statements in both Phases 1 and 2 (refer to Additional file 1 : Appendices B.1 and D.3, respectively, for all of the statements in both phases), participants might have been able to recall the statements at higher rates than if the statements were less memorable. This can be explored in future studies by having participants read multiple lists of relatively ordinary sentences and testing them on their memory of the sentences and where the sentences can be found.

The results of Phase 2 present significant potential and interest for further research. For example, studies may investigate the degree of permanence of transactive memory systems. From the perspective of cognitive neuroscience, studies could also investigate the neural changes that may potentially contribute to the strengthening or weakening of transactive memory systems. The effect of “relatedness” between desired information and corresponding Internet storage locations could also be explored in future research.

Implications

The philosophical bases for how Internet use is to be understood has been called into question. Yet, notwithstanding the numerous perspectives—including of transactive memory, extended memory, and memory scaffolds—that have been brought into such discussion, this study furthers the understanding of psychological phenomena at play in digital, Internet-based knowledge acquisition [ 8 , 13 , 14 , 15 ]. The presented findings would still hold regardless of which perspective is accepted.

The choice to administer experimental memory task surveys via Google Forms reflects the fundamental aims of the study design—to simulate Internet use through the “online” nature of the administered surveys, the use of “Google” services, and a completely digitized study design able to be completed on any Internet-connected device reflecting the Internet’s decentralization. Although transactive memory systems may take varying forms even within Internet use (e.g., cognitive associations with hyperlinks and site maps), the fundamental nature of Internet use in a transactive memory system—associating certain “keywords”, locations, hyperlinks, or website names (rather than URLs) that store and/or which lead to the desired information—is consistent, suggesting applicability of this study’s findings to digital, Internet-based means of knowledge and information exchange [ 16 , 17 ]. Yet, studies have indicated differences in how and when such Internet features effectively improve (semantic) memory of desired information [ 18 ]. This study’s design may be akin to what has been termed by some authors as “site maps” or “knowledge maps” (see Additional file 1 : Appendices B and D for visual tables of statements provided in memory task surveys), providing users a holistic, often visual representation of the Internet information landscape of interest before memory is assessed. Thus the implications of this study’s findings may be relevant for at least such site maps.

This study sheds light on the ethics of psychological research and gives rise to relevant questions for consideration. Ethical and philosophical topics, issues, and dilemmas relevant to the novel findings of this study include but are not limited to: mental health and declining social interaction with human transactive memory sources (friends, colleagues, etc.), causality and impact analysis of disparities in Internet accessibility, impact of Internet-based transactive memory use on sense of self and relevant perspectives (e.g., extended mind perspective), privacy and informed consent in memory modification, cognitive responsibilities (e.g., to remember or forget) in social settings given the default of Internet-based devices to store or “technologically remember” information, permanence of transactive memory systems with the Internet, and humanity in an age of rapid technological progress [ 4 , 8 , 19 , 20 , 21 ].

Such concerns involve careful scientific, ethical, legal, and social judgement [ 4 ]. Considering topics such as those discussed above will be beneficial for the sectors of science, government, and the public to establish strong and agreeable ethical boundaries and ensure equity and social justice as society progresses into the future.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated during this study are included in this article and its supplementary information files.

Andrews E. Who invented the Internet? http://www.history.com/news/who-invented-the-internet (2013). Accessed 7 Mar 2020.

Internet Growth Statistics. (n.d.). http://www.internetworldstats.com/emarketing.htm (n.d.). Accessed 22 Mar 2020.

Angers L. What can transactive memory tell us? http://www.betterhelp.com/advice/memory/what-can-transactive-memory-tell-us/ (2018). Accessed 6 Jan 2020.

Beverly JM, Blumenrath S, Chiu L, Davis A, Fessenden M, Galinato M, Halber D, Hopkin K, Kelly D, Parks C, Richardson M, Rojahn S, Sheikh KS, Weintraub K, Wessel L, Wnuk A, Zyla G. Brain facts: a primer on the brain and nervous system. 2018;121:33–34, Accessed 22 Mar 2020.

Transactive Memory. (n.d.). http://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/psychology/transactive-memory . Accessed 7 Jan 2020.

Transactive Memory: Transactive memory definition. http://psychology.iresearchnet.com/social-psychology/interpersonal-relationships/transactive-memory/ (2013). Accessed 6 Jan 2020.

Wegner DM. Transactive memory: a contemporary analysis of the group mind. In: Theories of group behavior. New York: Springer; 1987. pp. 185–208.

Kourken M, Sutton J. Memory. EN Zalta (Ed.), The stanford encyclopedia of philosophy (Summer 2017 Edition). https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2017/entries/memory/ (2017).

Sparrow B, Liu J, Wegner DM. Google effects on memory: cognitive consequences of having information at our fingertips. Science. 2011;333(6043):776–8.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Bjork RA. Theoretical implications of directed forgetting. In: Melton AW, Martin E, editors. Coding processes in human memory. Washington: Winston; 1972. p. 217–35.

Google Scholar

Lehman EB, Morath R, Franklin K, Elbaz V. Knowing what to remember and forget: a developmental study of cue memory in intentional forgetting. Mem Cognit. 1998;26(5):860–8.

Hyde TS, Jenkins JJ. Differential effects of incidental tasks on the organization of recall of a list of highly associated words. J Exp Psychol. 1969;82(3):472–81.

Article Google Scholar

Clowes RW. The cognitive integration of E-memory. Rev Philos Psychol. 2013;4(1):107–33.

Clowes R. Thinking in the cloud: the cognitive incorporation of cloud-based technology. Philos Technol. 2015;28(2):261+.

Heersmink R, Sutton J. Cognition and the web: extended, transactive, or scaffolded? Erkenntnis. 2020;85(1):139–64.

Rotondi AJ, Eack SM, Hanusa BH, Spring MB, Haas GL. Critical design elements of e-health applications for users with severe mental illness: singular focus, simple architecture, prominent contents, explicit navigation, and inclusive hyperlinks. Schizophr Bull. 2015;41(2):440–8.

Seufert T, Jänen I, Brünken R. The impact of intrinsic cognitive load on the effectiveness of graphical help for coherence formation. Comput Hum Behav. 2007;23(3):1055–71.

May MD, Sundar SS, Williams RB. The effects of hyperlinks and site maps on the memorability and enjoyability of web content. In: Communication & technology division at the 47th annual conference of the international communication association (1997).

Nagam VM. Internet-based technology, memory, and neuroethics: ethical implications of our cognitive relationships with the Internet and ensuring social justice in an age of rapid technological progress. In: 2021 International neuroethics society annual meeting (2021).

Madan CR. Augmented memory: a survey of the approaches to remembering more. Front Syst Neurosci. 2014;8:30.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Nagam VM. Implant neurotechnologies for memory and cognition: a literary approach to memory ethics and medicine. In: 2022 international neuroethics society annual meeting (2022)

Download references

Acknowledgements

The author of this study gratefully acknowledges the guidance and support in the experimental design process provided by Dr. Madhu Budamagunta, Ph.D. (Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Medicine, University of California, Davis) and Mrs. Suekyung Baker. Thanks to Dr. Phani Vadarevu, M.D. (Geriatric Medicine, Kaiser Permanente) and Mrs. Daria Muller for reviewing the experimental design and assisting with the paperwork necessary for conducting this study. Many thanks to all of the participants, who made this study possible.

All funding was provided by the author of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, USA

Vishruth M. Nagam

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

VN initiated the study, performed all data analysis, and authored and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Vishruth M. Nagam .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Informed consent was obtained from all participants or, if participants are under 18, from a parent and/or legal guardian (refer to Additional file 1 : Appendix A for the Human Informed Consent Form administered). All experimental protocols were approved by an Intel ISEF Affiliated Fair Scientific Review Committee. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The author declares that there are no competing interests for the publication of this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

. Appendices

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Nagam, V.M. Internet use, users, and cognition: on the cognitive relationships between Internet-based technology and Internet users. BMC Psychol 11 , 82 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-023-01041-5

Download citation

Received : 24 July 2021

Accepted : 04 January 2023

Published : 27 March 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-023-01041-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Transactive memory

- Semantic memory

BMC Psychology

ISSN: 2050-7283

- General enquiries: [email protected]

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- PMC10056218

Problematic Internet Use and Resilience: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Sergio hidalgo-fuentes.

1 Departamento de Psicología y Salud, Universidad a Distancia de Madrid (UDIMA), Crta. De la Coruña Km. 38,500, vía de Servicio Número 15, Collado Villalba, 28400 Madrid, Spain

2 Departamento de Psicología Básica, Universitat de València, Avgda. Blasco Ibañez 21, 46010 Valencia, Spain

Manuel Martí-Vilar

Yolanda ruiz-ordoñez.

3 Departamento de Psicología Básica, Neuropsicología y Social, Universidad Católica de Valencia, 46100 Burjassot, Spain

Associated Data

Not applicable.

Problematic Internet use has become a major problem worldwide due to its numerous negative correlates in the field of health, both mental and physical, and its increasing prevalence, making it necessary to study both its risk and protective factors. Several studies have found a negative relationship between resilience and problematic Internet use, although the results are inconsistent. This meta-analysis assesses the relationship between problematic Internet use and resilience, and analyses its possible moderating variables. A systematic search was conducted in PsycInfo, Web of Science and Scopus. A total of 93,859 subjects from 19 studies were included in the analyses. The results show that there is a statistically-significant negative relationship ( r = −0.27 (95% CI [−0.32, −0.22])), without evidence of publication bias. This meta-analysis presents strong evidence of the relationship between the two variables. Limitations and practical implications are discussed.

1. Introduction

Internet use has grown substantially over the last few decades, with the number of users increasing by 1331.9% between 2000 and 2021 [ 1 ], when a total of 4.66 billion users were counted, representing approximately 60% of the world’s population [ 2 ]. The benefits associated with using the Internet, especially concerning information search and communication, have led people to rely more and more on this technology for their work, study, social interaction and access to various entertainment options [ 3 ]. However, excessive and uncontrolled use of this technology can lead to what has been termed problematic Internet use (PIU), which is defined as Internet use that causes psychological, social, educational and/or occupational difficulties in an individual’s life [ 4 ]. Although the term Internet addiction, conceptualized as an impulse control disorder whereby the person loses control over their use of the Internet to the extent that they experience numerous negative consequences, as proposed by Young [ 5 ], is widely used in the scientific literature [ 6 ], a considerable number of authors recommend the use of PIU as more appropriate [ 7 , 8 , 9 ], since it is not recognised as an addictive disorder in either the DSM-5 [ 10 ] or ICD-11 [ 11 ].

PIU has been associated with numerous negative variables related to both mental and physical health, such as anxiety and depression [ 12 ], low self-esteem [ 13 ], poor sleep quality [ 14 ], alexithymia [ 15 ], risk of obesity [ 16 ], high impulsivity [ 17 ] and problematic alcohol consumption [ 18 ], among others, and the World Health Organization has declared PIU a major public health concern, emphasizing the need to intensify international research on this problem to generate the information required to develop policies and interventions to prevent and treat PIU [ 19 ]. A recent meta-analysis, which was conducted on a total sample of 2,123,762 people, has estimated the prevalence of PIU among the general population at 14.22% [ 20 ], having increased in recent years [ 21 ]. The high number of detrimental variables associated with PIU, as well as its increasing prevalence, makes it necessary to emphasize the study of both potential risk factors and protective factors for PIU.

How to conceptualize resilience is a widely debated topic in the field of psychology [ 22 ]. Resilience can be defined as an individual’s ability to maintain or regain psychological well-being in the face of a challenging situation [ 23 ]; it is a dynamic process that encompasses positive adaptation in the face of significant adversity, which would include feedback, learning and making changes to remain positive and recover from frustration caused by stressful events [ 24 ]. Resilience is an important factor in personal well-being, being negatively correlated to negative indicators of mental health, such as depression and anxiety, and positively correlated to positive indicators of mental health, such as life satisfaction and positive affect [ 25 ]. Several studies have examined the role of resilience in various types of addictive behaviors, and have found that resilience serves as a protective factor against addiction to gambling [ 26 ], alcohol [ 27 , 28 ], drugs of abuse [ 29 , 30 ], and video games [ 31 , 32 ]. Likewise, the relationship between resilience and PIU has also been evaluated, and has found negative relationship between both variables [ 33 , 34 , 35 ]. However, to date there has been no meta-analysis specifically focused on the relationship between PIU and resilience that synthesizes the results found. The aim of this paper is therefore to synthesize the evidence from those studies that have examined the association between PIU and resilience by answering the following research questions: (1) what is the strength of the association between PIU and resilience?; and (2) is the association between PIU and resilience moderated by the methodological and socio-demographic variables of the studies analyzed?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. systematic search.

This meta-analysis (registered in PROSPERO database #CRD42022382337) was conducted according to the criteria of the PRISMA statement [ 36 ] ( Appendix A , Table A1 ). A systematic search was conducted during November 2022 in three databases (PsycINFO, Scopus and Web of Science) using the terms (resilience OR resiliency OR resilient) AND (internet addiction OR problematic internet use OR internet abuse OR internet overuse OR internet dependence). Searches were restricted to papers published in English or Spanish. Moreover, the references of the selected articles were manually checked for other relevant studies that were not retrieved during the electronic search. The systematic reviews software Covidence ( http://www.covidence.org accessed on 14 November 2022) was used to manage the study selection process.

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

The retrieved studies were selected based on the following inclusion criteria: (1) original empirical and quantitative cross-sectional or longitudinal studies; (2) published in peer-reviewed scientific journals; (3) published in English or Spanish; (4) include assessments of PIU and resilience; (5) present Pearson’s correlation coefficient between PIU and resilience or the statistical data necessary to calculate it: (6) present the sample size; and (7) the full text was available. In case of studies with partially duplicated samples, the study with the largest sample size was selected.

2.3. Methodological Quality of Included Studies

Conducting a meta-analysis without taking into consideration the methodological quality of the included studies may lead to biased results. Therefore, an assessment of the methodological quality of the studies analyzed in a meta-analysis is essential to be able to draw reliable conclusions. The risk of individual bias of the studies included in the meta-analysis was assessed using the short version of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale developed by Deng et al. [ 37 ]. The scale consists of a total of five items: (1) representativeness of the sample (inclusion of the entire population or random sampling); (2) sample size justified by methods such as power analysis; (3) response rate greater than 80%; (4) valid PIU and resilience assessment tests; and (5) appropriate and correctly described statistical analyses. Each item is scored as one point if it meets the criterion and zero points if it does not meet the criterion or the information is not available. The total score ranges from zero to five points, with studies scoring three or more points being considered at low risk of individual bias and those scoring less than three points being considered at high risk of individual bias. Assessments were performed by two reviewers working independently. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus.

2.4. Data Coding

A recording sheet was prepared to code the following information for the studies included: author(s), year of publication, country in which the study was conducted, continent, sample size, mean age of participants, gender (coded as the percentage of males in the sample), test used to assess PIU, test used to assess resilience, risk of individual bias and Pearson’s correlation between PIU and resilience. Data coding was performed by two reviewers working independently. The reviewers matched their data after extraction and revisited papers in case of disagreements. In the event of missing data, we contacted the authors of the study to request the necessary information; where we received no response or the authors refused to provide it, the information is listed as missing. To meet the independence assumption, in the case of longitudinal studies only the first correlation between PIU and resilience was coded.

2.5. Data Analysis

Most of the studies had Pearson correlations. For those studies with χ 2 , this result was converted to Pearson correlations using the formula r = √( χ 2 /n). Subsequently, to normalize their distributions, all Pearson correlations were converted to Fisher’s Z-scores using the formula Z = 0.5 × ln[(1 + r )/(1 − r )]. All analyses were performed with Z-scores, although the overall effect size and its confidence interval were transformed back to Pearson correlations for better interpretation following the recommendation of Borenstein et al. [ 38 ].

Due to the variability observed in the selected studies in terms of the countries in which they were conducted, the number of subjects and tests used, a random-effects meta-analysis with the restricted maximum likelihood method was chosen. Random-effects models generally produce more precise estimates and allow for greater generalizability of results [ 39 , 40 , 41 ]. The existence of statistically significant heterogeneity among the effect sizes of the analyzed studies was examined using Cochran’s Q test, while the degree of true heterogeneity not explained by random sampling error was assessed using the I 2 statistic. I 2 values of 25%, 50% and 75% are interpreted respectively as low, moderate and high heterogeneity [ 42 ].

The validity of a meta-analysis may be challenged by the presence of publication bias, a phenomenon whereby studies with statistically significant results or high effect sizes are more likely to be published [ 43 ]. Publication bias is a particularly important problem when conducting meta-analyses, since it can lead to overestimated effect sizes. In this study, and as recommended by Botella and Sánchez-Meca [ 44 ], the risk of publication bias was assessed by several methods: visual inspection of the funnel plot, Egger’s regression test [ 45 ], Begg and Mazumdar’s rank correlation test [ 46 ], and calculating the safety number according to Rosenthal’s method. In the absence of publication bias, the funnel plot will be symmetrical around the average effect size, while Egger’s test and Begg and Mazumdar’s test will show non-significant results. Rosenthal’s method makes it possible to estimate missing studies to calculate how many studies would be required for the estimated effect size to be non-significant.

A jacknife sensitivity analysis was performed, estimating the pooled effect size while eliminating each study alternatively, to assess the individual influence on the overall effect size of each of the studies included in the meta-analysis.

We examined the possible moderating role of the following variables: sex and age of participants, measures for assessing PIU and resilience, the continent in which the studies were conducts, individual risk of bias and year of publication. For continuous variables, meta-regression analyses were conducted, while for categorical variables, subgroup analyses were conducted. For subgroup analysis, and as recommended by Fu et al. [ 47 ], each subgroup should be composed of a minimum of four studies. When this was not possible due to fewer studies having been performed, the remaining studies were grouped into the subgroup others and included in the analyses under this heading if they comprised at least four studies. The percentage of variance explained by the moderators was assessed using the R 2 index.

Analyses were performed in R Studio using the metafor statistical package [ 48 ].

As can be seen in Figure 1 , the search and selection process ended with the inclusion of 19 studies that met the inclusion criteria. The selected articles were published between 2015 and 2022 (see Table 1 ). Eight of the studies were conducted in China, four in South Korea, two in the United States and Turkey, and one each in Australia, Hungary and Iran. The combined sample was 93,859 subjects, with the sample sizes of the various studies ranging from 96 to 58,756 participants.

PRISMA diagram of the search and selection process.

Summary of studies included in the meta-analysis.

| Study | Country | Continent | Sample | Age | Sex (% Men) | PIU Test | Resilience Test | Risk of Bias | r |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cao et al., 2020 [ ] | China | Asia | 1218 | 11.8 | 55.25 | YDQ | CD-RISC 10 | Under | −0.214 |

| Choi et al., 2015 [ ] | South Korea | Asia | 448 | 20.89 | 39.7 | IAT | CD-RISC | Under | −0.12 |

| Cui & Chi, 2021 [ ] | China | Asia | 2544 | 16.49 | 42.7 | YDQ | CD-RISC 10 | Under | −0.267 |

| Dinc & Topcu, 2021 [ ] | Australia | Oceania | 220 | 14.16 | 44.5 | CIUS | CYRM-28 | High | −0.29 |

| Dong & Li, 2020 [ ] | China | Asia | 1362 | 53.9 | IAII | CD-RISC 10 | Under | −0.25 | |

| Hsieh et al., 2021 [ ] | China | Asia | 6233 | 51 | CIAS | CD-RISC 10 | Under | −0.17 | |

| Jin et al., 2019 [ ] | USA | America | 326 | 23.4 | 20.6 | IAT | BRS | Under | −0.121 |

| Kiss et al., 2020 [ ] | Hungary | Europe | 249 | 22.5 | 37.8 | PIU-Q | CD-RISC 10 | High | −0.274 |

| Lee et al., 2022 [ ] | South Korea | Asia | 866 | 70.8 | IAPS | CD-RISC | High | −0.39 | |

| Mak et al., 2018 [ ] | South Korea | Asia | 837 | 22.13 | 43.13 | IAT | CD-RISC | High | −0.4 |

| Nam et al., 2018 [ ] | South Korea | Asia | 519 | 51.64 | IAT | CD-RISC | High | −0.122 | |

| Öztürk & Kundakçı, 2021 [ ] | Turkey | Europe | 1028 | 20.17 | 39.7 | IAT | BRS | Under | −0.498 |

| Peng et al., 2021 [ ] | China | Asia | 16,130 | 15.22 | 51.9 | IAT | RSCA | Under | −0.252 |

| Robertson et al., 2018 [ ] | USA | America | 240 | 25.05 | 65 | IAT | CD-RISC | High | −0.36 |

| Saeed, 2020 [ ] | China | Asia | 436 | 23.81 | IAT | BRS | High | −0.15 | |

| Salek-Ebrahimi et al., 2019 [ ] | Iran | Asia | 96 | 19.73 | 21.1 | IAT | CD-RISC | Under | −0.222 |

| Yilmaz et al., 2022 [ ] | Turkey | Europe | 1123 | 46.7 | 58 | YIAT-SF | BRS | Under | −0.346 |

| Zhang & Li, 2022 [ ] | China | Asia | 1228 | YDQ | PPQ | High | −0.38 | ||

| Zhou et al., 2017 [ ] | China | Asia | 58,756 | 10.83 | 54.5 | YDQ | RRS | High | −0.218 |

YDQ: Young’s Diagnostic Questionnaire for Internet Addiction; IAT: Young’s Internet Addiction Test; CIUS: Compulsive Internet Use Scale; IAII: Internet Addiction Impairment Index; CIAS: Chen Internet Addiction Scale; PIU-Q: Problematic Internet Use Questionnaire; IAPS: Korean Internet Addiction Proneness Scale for Youth; YIAT-SF: Young’s Internet Addiction Test-Short Form; CD-RISC 10: Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale Short Form; CD-RISC: Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale; CYRM-28: Child and Youth Resilience Measure; BRS: Brief Resilience Scale; RSCA: Resilience Scale for Chinese Adolescents; PPQ: PsyCap Questionnaire; RRS: Revised Resilience Scale.

The estimated overall effect size for the correlation between PIU and resilience was Z r = −0.28 (95% CI [−0.33, −0.22]), which transformed back to Pearson’s correlation gives a result of r = −0.27 (95% CI [−0.32, −0.22]), and which, following the interpretation criteria proposed by Cohen [ 65 ], can be classified as a moderate intensity correlation. The forest plot of the effect sizes and 95% confidence intervals of the 19 studies are shown in Figure 2 . As can be seen in the figure, the effect sizes of the studies ranged from Z r = −0.12 to Z r = −0.55. The Cochran’s Q test result was 281.4128, p < 0.0001, hence the homogeneity hypothesis is rejected, while the I 2 value reached a value of 97.46%, which is considered high according to Higgins and Thompson’s criteria [ 42 ].

Effect size for the relationship between PIU and resilience [ 33 , 34 , 35 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 , 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 ].

Although the funnel plot is not fully symmetrical (see Figure 3 ), both the Egger regression test ( z = 0.2996, p = 0.76) and the Begg and Mazumdar rank correlation test (τ = −0.0292, p = 0.89) show non-significant results, thus ruling out the presence of publication bias. Likewise, the calculation of the number of safety according to Rosenthal’s method yielded a value of n = 18,877 ( p < 0.001), making 18,877 unpublished studies with an effect size equal to zero necessary to make the p -value non-significant, exceeding the critical value which, for this meta-analysis, is set at 105 studies, according to the formula (5 × k) + 10, and k being the number of studies included in the meta-analysis [ 44 ].

Funnel plot for assessing publication bias.

The sensitivity analysis, performed using the jackknife method, did not show excessive individual influence of any of the studies on the estimated overall effect size, with the effect size ranging from Z r = −0.26 to Z r = −0.29 when alternately omitting each of the studies.

Meta-regression analyses were conducted to examine the possible moderating effect of year of publication, mean age of participants and percentage of males in the sample on the correlation between PIU and resilience. Both mean age ( b = −0.0028, p = 0.72) and percentage of males among participants ( b = −0.0027, p = 0.26) did not show up as moderating variables, while year of publication ( b = −0.0283, p = 0.04) does moderate the relationship between the two variables, with a total explained variability of 16.55%, with more recent studies showing lower correlations.

For categorical variables, subgroup analyses were performed (see Table 2 ), and no moderating effect was found for any of the variables analyzed.

Relationship between PIU and resilience: moderation analysis for categorical variables.

| 95% CI | Subgroup | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk of individual bias | 0.48 | |||

| High | −0.30 | −0.38, −0.22 | <0.001 | |

| Under | −0.26 | −0.33, −0.18 | <0.001 | |

| Continent | 0.15 | |||

| Asia | −0.25 | −0.32, −0.19 | <0.001 | |

| Other | −0.34 | −0.44, −0.24 | <0.001 | |

| PIU test | 0.90 | |||

| IAT | −0.27 | −0.35, −0.18 | <0.001 | |

| YDQ | −0.28 | −0.40, −0.16 | <0.001 | |

| Other | −0.30 | −0.40, −0.19 | <0.001 | |

| Resilience test | 0.87 | |||

| BRS | −0.30 | −0.43, −0.18 | <0.001 | |

| CD-RISC | −0.28 | −0.39, −0.18 | <0.001 | |

| CD-RISC 10 | −0.24 | −0.35, −0.13 | <0.001 | |

| Other | −0.29 | −0.42, −0.17 | <0.001 |

4. Discussion

The first aim of this paper was to estimate the magnitude of the association between PIU and resilience. Additionally, we examined the possible moderating role of gender and age of participants, the continent on which the studies were conducted, the tests used to assess both PIU and resilience, the year of publication of the studies, and the risk of individual bias.

The systematic search identified a total of studies that met the inclusion criteria with a total sample of 93,859 subjects. The results of the meta-analyses showed a statistically significant negative correlation of moderate intensity ( r = −0.27) between the two variables, whereby those who showed higher levels of resilience had lower levels of PIU. Sensitivity analysis reveals that this result is consistent, with none of the studies having an excessive influence on the overall effect size. Furthermore, the various tests performed to assess the risk of publication bias ruled out the presence of bias. Despite the high degree of heterogeneity found, only the year of publication proved to be a moderating variable in the correlation between PIU and resilience, explaining 16.55% of the observed heterogeneity.

The result found has important implications for the prevention of PIU, a phenomenon with significant negative repercussions on mental and physical health, as well as significant associated economic costs [ 66 ]. Resilience may function as a protective factor for PIU by mitigating the negative impact of adverse situations or environments, causing individuals to suffer lower levels of depression or anxiety [ 67 ], two variables that have been consistently linked in the scientific literature to PIU [ 12 , 68 , 69 , 70 ]. Additionally, in theoretical terms, the negative association found between resilience and PIU could be explained in relation to the I-PACE model, which explains the onset and development of PIU by the interaction of personal, affective, cognitive and executive variables [ 6 ]. This theoretical model holds that stress is an important factor operating on addictive behaviors and that excessive and uncontrolled use of the Internet can sometimes be a coping style that attempts to cope with this stress. Resilience also improves people’s ability to cope with stressful situations, which are also a risk factor for PIU [ 71 ], as individuals with high levels of stress often use the Internet as a maladaptive coping strategy because, although it does not offer long-term improvement, Internet use can serve as a temporary relief from stressful symptoms. Thus, from this perspective, resilience, which is taken to be the ability to cope with adverse and stressful situations, may lead to a lesser need to use the Internet to reduce stress levels, since resilience itself will act as a protective factor. Thus, people with higher levels of resilience have and make use of adaptive coping strategies in stressful situations, which may prevent them from engaging in compulsive behaviors such as PIU. Therefore, the results obtained, together with the fact that resilience can be increased through appropriate programs [ 72 ], allow us to state that interventions aimed at increasing resilience can be an effective method of reducing the risk of PIU. Besides preventing the onset of PIU, resilience has also shown benefits when IPU has already developed, serving as a protective factor against the negative psychological effects of PIU [ 73 ].

Among the possible moderating variables of the relationship between PIU and resilience examined, the only statistically significant moderator was the studies’ year of publication, with more recent articles showing a smaller effect size among the variables studied. One possible explanation for this is that the more recent studies, conducted during the pandemic when many countries were in lockdown, show a lower relationship between PIU and resilience since individuals during this period suffered greater stress that could not be compensated for by their resilience levels, leading to excessive internet use to reduce this stress. By contrast, participants’ gender and age, as well as the geographical area in which the studies were conducted, are not statistically significant moderators of the relationship between PIU and resilience. The fact that there is little heterogeneity regarding these variables, especially age and geographic area, in the included studies could be influencing this result.

The results of this meta-analysis should be interpreted with caution due to certain limitations. Firstly, the number of studies that met the inclusion criteria is limited, so it would be advisable for future systematic reviews or meta-analyses to extend the search to other databases. Secondly, only studies published in Spanish or English were included, which could be considered a selection bias, despite English being the most widely used language in the scientific literature. Thirdly, only one of the possible moderating variables was found to have a significant effect and it could not explain a significant percentage of the heterogeneity found. It would therefore be important for future meta-analyses to examine the role of new potential moderators of the correlation between PIU and resilience, such as the population in which the studies were carried out or the scores obtained. Fourth, given the cross-sectional design of most of the included studies, it is not possible to establish causal relationships between the variables analyzed or to examine their evolution over time, hence it would be desirable to conduct further longitudinal or experimental design research in the future to examine these matters. Finally, most of the studies were conducted in Asian countries and with adolescent and young participants, with very limited research in other geographical areas and with subjects in other age groups.

5. Conclusions

PIU has become a growing problem in recent years, especially among adolescents and young people, being associated with many harmful variables, mainly psychological, hence studying its risk and protective factors to help to prevent and treat it should be a priority, bearing in mind both its negative effects and the number of people who suffer from this problem. This meta-analysis has synthesized the results on PIU and resilience. The results of this review, despite its limitations, indicate the existence of a significant negative relationship of moderate intensity between both variables that does not appear to depend on age, gender, geographical area or the tests used. This result has implications that go beyond the theoretical field by supporting the fact that working on people’s resilience can reduce the risk of PIU. Moreover, increasing resilience levels through appropriate training programs would have beneficial effects beyond reducing the risk of IPU, since resilience has also been shown to be a protective factor against other addictive behaviors such as alcohol consumption [ 27 ], gambling [ 26 ], drug abuse [ 29 ] and Internet gaming disorder [ 32 ]. Likewise, increasing resilience would also have a positive impact on other variables not directly related to problematic use of new technologies or addictions, improving both physical and mental health [ 72 ].

Search Strings; PRISMA Checklist.

| Section/Topic | # | Checklist Item | Reported on Page # |

|---|---|---|---|

| Title | 1 | Identify the report as a systematic review, meta-analysis, or both. | 1 |

| Structured summary | 2 | Provide a structured summary including, as applicable: background; objectives; data sources; study eligibility criteria, participants, and interventions; study appraisal and synthesis methods; results; limitations; conclusions and implications of key findings; systematic review registration number. | 1 |

| Rationale | 3 | Describe the rationale for the review in the context of what is already known. | 1–2 |

| Objectives | 4 | Provide an explicit statement of questions being addressed with reference to participants, interventions, comparisons, outcomes, and study design (PICOS). | 2 |

| Protocol and registration | 5 | Indicate if a review protocol exists, if and where it can be accessed (e.g., Web address), and, if available, provide registration information including registration number. | 2 |

| Eligibility criteria | 6 | Specify study characteristics (e.g., PICOS, length of follow-up) and report characteristics (e.g., years considered, language, publication status) used as criteria for eligibility, giving rationale. | 2 |

| Information sources | 7 | Describe all information sources (e.g., databases with dates of coverage, contact with study authors to identify additional studies) in the search and date last searched. | 2 |

| Search | 8 | Present full electronic search strategy for at least one database, including any limits used, such that it could be repeated. | |

| Study selection | 9 | State the process for selecting studies (i.e., screening, eligibility, included in systematic review, and, if applicable, included in the meta-analysis). | 2 |

| Data collection process | 10 | Describe method of data extraction from reports (e.g., piloted forms, independently, in duplicate) and any processes for obtaining and confirming data from investigators. | 2–3 |

| Data items | 11 | List and define all variables for which data were sought (e.g., PICOS, funding sources) and any assumptions and simplifications made. | 2–3 |

| Risk of bias in individual studies | 12 | Describe methods used for assessing risk of bias of individual studies (including specification of whether this was done at the study or outcome level), and how this information is to be used in any data synthesis. | 2 |

| Summary measures | 13 | State the principal summary measures (e.g., risk ratio, difference in means). | 3 |

| Synthesis of results | 14 | Describe the methods of handling data and combining results of studies, if done, including measures of consistency (e.g., ) for each meta-analysis. | 3 |

| Risk of bias across studies | 15 | Specify any assessment of risk of bias that may affect the cumulative evidence (e.g., publication bias, selective reporting within studies). | 3 |

| Additional analyses | 16 | Describe methods of additional analyses (e.g., sensitivity or subgroup analyses, meta-regression), if done, indicating which were pre-specified. | 3 |

| Study selection | 17 | Give numbers of studies screened, assessed for eligibility, and included in the review, with reasons for exclusions at each stage, ideally with a flow diagram. | 3–4 |

| Study characteristics | 18 | For each study, present characteristics for which data were extracted (e.g., study size, PICOS, follow-up period) and provide the citations. | 4–5 |

| Risk of bias within studies | 19 | Present data on risk of bias of each study and, if available, any outcome level assessment (see item 12). | 4–5 |

| Results of individual studies | 20 | For all outcomes considered (benefits or harms), present, for each study: (a) simple summary data for each intervention group (b) effect estimates and confidence intervals, ideally with a forest plot. | 5 |

| Synthesis of results | 21 | Present results of each meta-analysis done, including confidence intervals and measures of consistency. | 5–6 |

| Risk of bias across studies | 22 | Present results of any assessment of risk of bias across studies (see Item 15). | 5–6 |

| Additional analysis | 23 | Give results of additional analyses, if done (e.g., sensitivity or subgroup analyses, meta-regression [see Item 16]). | 6–7 |

| Summary of evidence | 24 | Summarize the main findings including the strength of evidence for each main outcome; consider their relevance to key groups (e.g., healthcare providers, users, and policy makers). | 7 |

| Limitations | 25 | Discuss limitations at study and outcome level (e.g., risk of bias), and at review-level (e.g., incomplete retrieval of identified research, reporting bias). | 7 |

| Conclusions | 26 | Provide a general interpretation of the results in the context of other evidence, and implications for future research. | 7–8 |

| Funding | 27 | Describe sources of funding for the systematic review and other support (e.g., supply of data); role of funders for the systematic review. | N/A |

From: [ 36 ]. For more information, visit: www.prisma-statement.org (accessed on 17 December 2022).

Funding Statement

This research received no external funding.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.H.-F. and M.M.-V.; methodology, S.H.-F., M.M.-V. and Y.R.-O.; software, S.H.-F.; validation, S.H.-F., M.M.-V. and Y.R.-O.; formal analysis, S.H.-F.; investigation, S.H.-F., M.M.-V. and Y.R.-O.; resources, M.M.-V. and Y.R.-O.; data curation, S.H.-F.; writing—original draft preparation, S.H.-F.; writing—review and editing, M.M.-V. and Y.R.-O.; visualization, M.M.-V. and Y.R.-O.; project administration, M.M.-V. and Y.R.-O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed consent statement, data availability statement, conflicts of interest.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

We apologize for the inconvenience...

To ensure we keep this website safe, please can you confirm you are a human by ticking the box below.

If you are unable to complete the above request please contact us using the below link, providing a screenshot of your experience.

https://ioppublishing.org/contacts/

Does the more internet usage provide good academic grades?

- Open access

- Published: 06 June 2018

- Volume 23 , pages 2901–2910, ( 2018 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- V. Senthil ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8312-8912 1

24k Accesses

3 Citations

Explore all metrics

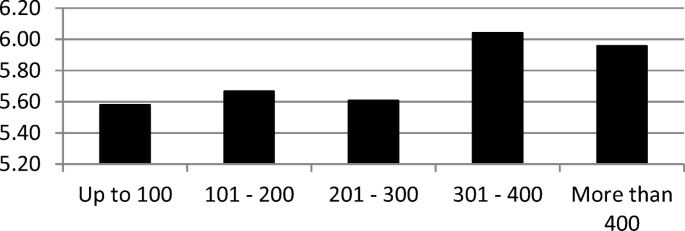

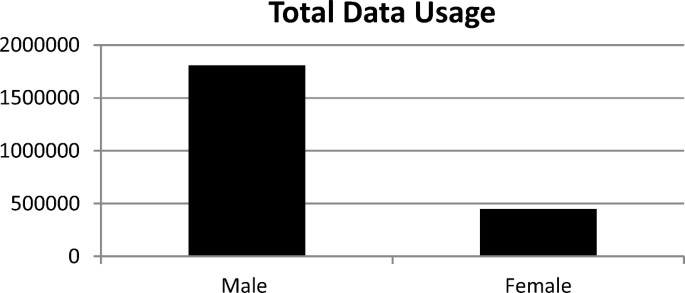

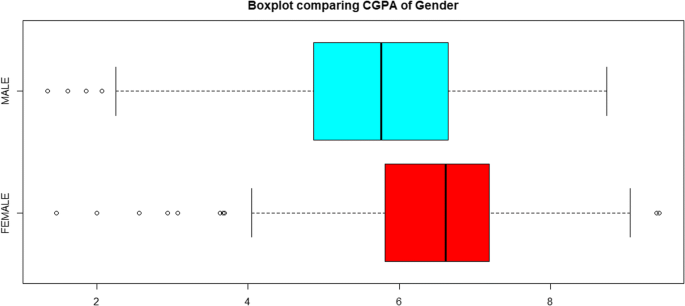

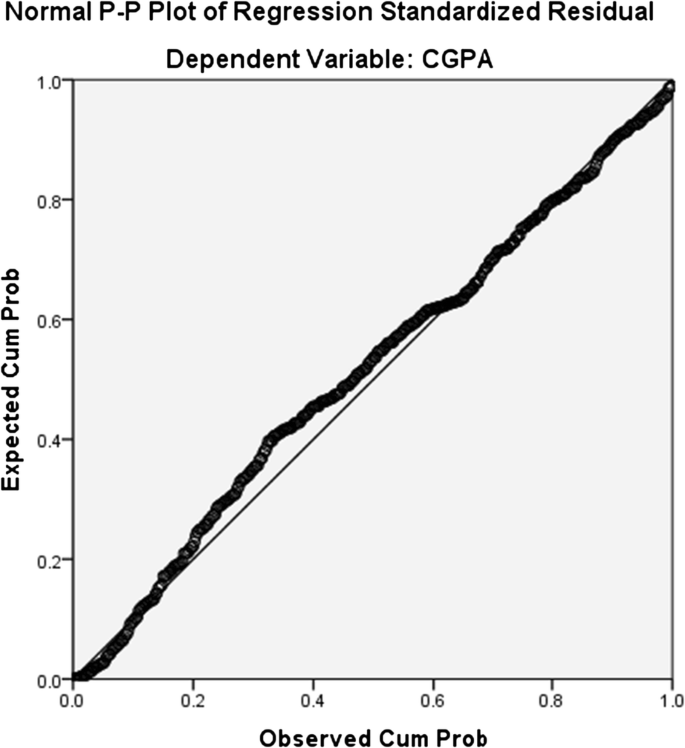

The Internet is an unavoidable resource to students for their day today academic activities and it is now occupies a central role in any academic environment. Student’s academic references have changed dramatically in the recent years. The present day students spending more time on internet and their reading and reference style is changed drastically from the traditional methods. Many students have replaced their text books, reference books and daily newspapers with online editions. The internet behaviours such as data usage (upload, download) and visiting number of websites to their positive (or negative) effect on Cumulative Grade Point Average (CGPA) are analysed in this paper. The sample data in an academic environment is used in this research to elicit the impact on their academic performance. Both descriptive and inferential statistical methods are applied in this research and the research results indicated that internet usage has a marginal impact on students’ academic performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Understanding the Impact of SNS on Education

Effects of Using E-Learning on Students’ Academic Performance in University College of Applied Sciences

Exploring the Factors Affecting Student Academic Performance in Online Programs: A Literature Review

Explore related subjects.

- Artificial Intelligence

- Digital Education and Educational Technology

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction