- COE Degrees & Programs

LTEC Learning Design & Technology

Appendix 2: design-based research (dbr) dissertations.

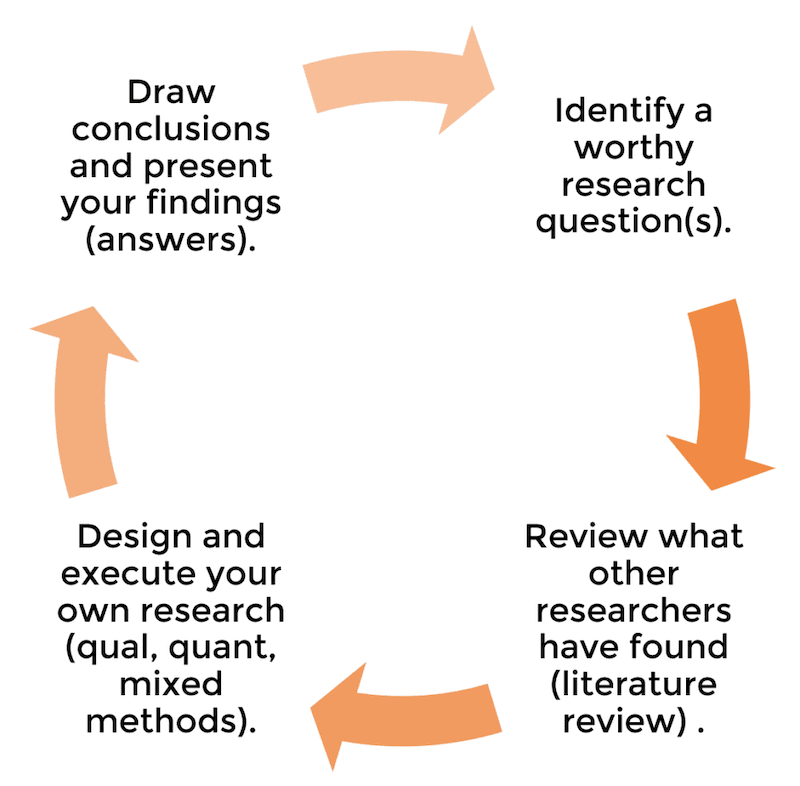

The core of the DBR dissertation is the research, development and testing of a product or process to solve an educational problem. Design-based research protocols require intensive and long-term collaboration involving researchers and practitioners. Design-based research integrates the development of solutions to practical problems in learning environments with the identification of reusable design principles. Barab and Squire (2004) defined design-based research as “a series of approaches, with the intent of producing new theories, artifacts, and practices that account for and potentially impact learning and teaching in naturalistic settings” (p. 2). They described it as a methodology that requires: addressing complex problems in real contexts in collaboration with practitioners integrating known and hypothetical design principles with technological affordances to render plausible solutions to these complex problems; and conducting rigorous and reflective inquiry to test and refine innovative learning environments as well as to define new design principles. A research proposal for a doctoral study using a design-based approach must include a practitioner-oriented focus as well as degrees of collaboration that are not necessarily required for more traditional predictive research designs.

A design-based research proposal consists of the following:

Phase 1: Problem Identification (Chapter 1)

For design-based research in education, the identification and exploration of a significant educational problem is a crucial first step. It is this problem that creates a purpose for the research, and it is the creation and evaluation of a potential solution to this problem that will form the focus of the entire study. Many research students begin by thinking of a solution—such as a technology-based intervention, an educational game, or a technology tool—before they consider the educational problem it could solve. Problems then arise when the solution is revealed to be a project of interest or ‘pet’ project, rather than a genuine attempt to solve an educational problem. The statement of the problem in design-based research should identify an issue or an opportunity, explore its history or background, and provide a convincing and persuasive argument that this problem is significant and worth researching. This includes articulating both the practical and scientific relevance of the study. In line with the exploratory nature of design research, driving questions should therefore be open in nature. The assumptions that direct DBR are derived from the definition of the research problem in close collaboration with practitioners.

Literature Review (Chapter 2)

The research is fine tuned through the literature review that serves to (a) help flesh out what is already known about the problem and (b) to guide the development of potential solutions. In such instances, the inquiry that forms the basis of DBR serves the researcher to help understand the underpinning processes and variables and how they impact on the learning and learning outcomes. A well-described theoretical framework provides a sound basis for the proposed solution, because theory can inform practical design guidelines. Even though they are largely based on the literature, it is unlikely that draft principles will be complete at the time the proposal is presented. At the very least, the process of deriving them should be described and examples given.

Description of proposed intervention (Chapter 3)

The proposed solution to the educational problem is developed from consideration of relevant literature, consultation and collaboration with researchers and practitioners, and as an instantiation of the principles derived from these sources. It is important to describe in the prospectus or proposal the process of how the intervention will be conceptualized and developed.

Methodology (Chapter 4)

The methodology serves to describe the Iterative cycles of testing and refinement of solutions in practice. Both qualitative and quantitative methods may be used in DBR. A research proposal would include details of the methodology of the implementation and evaluation of the proposed solution, as it largely constitutes the data collection and analysis stages of the study. The proposal should also acknowledge the likelihood, even the desirability in some cases, of significant modifications being required in the data collection and analysis phases of the ongoing study.

Implementation of intervention (First iteration – Alpha stage – prototyping)

The iterative nature of design-based research means that a single implementation is rarely sufficient to gather enough evidence about the success of the intervention and its effect on the problem situation. A typical design-based research study would have two or more cycles, where after the first implementation and evaluation, changes are made to the learning environment to further improve its ability to address the problem. In DBR the context of the inquiry must be seen as a means to an end rather than an end in itself. The intention should be to use the setting to gain an understanding which will have meaning beyond the immediate setting.

Participants

In a research proposal, the description of participants and the method of their selection provide important information for reviewers about the potential for bias in the proposed study. Participants are usually individuals who reflect the characteristics of or are influenced by the issues being considered by the investigation.

Data collection and analysis

The method of data collection in design-based research can involve the collection of qualitative and/or quantitative data, and it may be collected in cycles of several weeks or semesters, or even years. Types of data collected are likely to vary along with the phases. For example, data contributing to contextual understanding are more likely to be emphasized in earlier stages of the study, whereas data on prototype characteristics or user reactions are more likely to be collected later on. This section of the proposal describes (a) data sources such as varying time, location and participants; (b) data collection methods, including varying formats (interviews, observations, etc.); and (c) analysis approaches to be used with each data type.

Implementation of intervention—second and third iterations (Beta stage testing iteration and Gamma stage final assessment)

Although it is impossible to describe the nature of the second and subsequent iterations of the intervention, because they are so totally dependent on the findings of the first iteration, it is useful to describe the process that should be undertaken in the proposal. The cyclic nature of the data collection and analysis cannot be described in great detail in the proposal, but the process of data collection, analysis, further refinement, implementation and data collection (and so on) of the learning environment should be explained as a method in the proposal.

After the Proposal

Once the proposal is approved and IRB acquired, the student will begin collecting data for the Alpha stage which is then analyzed. Based on those findings, the intervention is adapted and then tested again in the Beta phase. After data collection and analysis in the Beta stage, the intervention is again modified and a final test (Gamma phase) with actual users is conducted.

Findings (Chapter 5)

In this chapter the researcher presents the findings of each iteration as well as describes the modifications made to the intervention based on the findings of each stage. The specific organization of the findings in Chapter 5 should be decided in consultation with the dissertation chair.

Conclusion (Chapter 6)

Reflection to produce “design principles” and enhance solution implementation

Design principles

The knowledge claim of design-based research, and one that sets it apart from other research approaches, takes the form of design principles. Design principles contain substantive and procedural knowledge with comprehensive and accurate portrayal of the procedures, results and context, such that readers may determine which insights may be relevant to their own specific settings. In the traditional sense, generalization of design-based research findings is rather limited; instead, use of design principles calls for a form of analytical generalization.

Practical outputs: Designed artifact(s)

In design -based research, the product of design is viewed as a major output . Design artifacts in this field may range from software packages to professional development programs, and many more.

Societal outputs: Professional development of participants

The collaboration that is so integral to the process of defining and accomplishing a design -based research project has an additional benefit to the extent that it enhances the professional development of all involved

Theoretical/Conceptual Framework and Literature Connections

The final chapter should also address how the findings from the research study compare and contrast with expectations based on the literature and the theoretical or conceptual framework used by the researcher.

The figure below shows a typical DBR process.

Other Content

As in the traditional and three-paper dissertation options, the dissertation will include appropriate Appendices and a full Reference list.

Design-based research requires frequent and prolonged periods of fieldwork, off-set by periods of review, reflection and re-design. These intervals should be clearly taken into account in any timeline accompanying the research proposal. A major strength of design research lies in its adaptability, the commitment to adjusting a study’s course based on findings after each iteration.

Committee Review

LTEC has adopted the following criteria taken as the basis for evaluation for a DBR dissertation beyond the metrics for a traditional dissertation:

- Appraise the intellectual merit of the research and the product/process proposed;

- Review the contribution to new or existing design principles

- Assess the quality and appropriateness of the practical solutions proposed for real-world educational problems

In general, the dissertation chair and committee are responsible for determining the appropriateness and quality of the proposed DBR research.

The format of the final dissertation must meet the style guidelines established by the UHM Graduate Division for theses and dissertations. All LTEC dissertations use APA style guidelines.

ISI Journals

- Informing Science: The International Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline (InformingSciJ)

- Journal of Information Technology Education: Research (JITE:Research)

- Journal of Information Technology Education: Innovations in Practice (JITE:IIP)

- Journal of Information Technology Education: Discussion Cases (JITE: DC)

- Interdisciplinary Journal of e-Skills and Lifelong Learning (IJELL)

- Interdisciplinary Journal of Information, Knowledge, and Management (IJIKM)

- International Journal of Doctoral Studies (IJDS)

- Issues in Informing Science and Information Technology (IISIT)

- Journal for the Study of Postsecondary and Tertiary Education (JSPTE)

- Informing Faculty (IF)

Collaborative Journals

- Muma Case Review (MCR)

- Muma Business Review (MBR)

- International Journal of Community Development and Management Studies (IJCDMS)

- InSITE 2025 : Jul 20 - 28 2025, Japan

- All Conferences »

- Publications

- Journals

- Conferences

Design Based Research in Doctoral Studies: Adding a New Dimension to Doctoral Research

Back to Top ↑

- Become a Reviewer

- Privacy Policy

- Ethics Policy

- Legal Disclaimer

SEARCH PUBLICATIONS

An Introduction to Design-Based Research with an Example From Statistics Education

- First Online: 01 January 2014

Cite this chapter

- Arthur Bakker 6 &

- Dolly van Eerde 6

Part of the book series: Advances in Mathematics Education ((AME))

10k Accesses

47 Citations

3 Altmetric

This chapter arose from the need to introduce researchers, including Master and PhD students, to design-based research (DBR). In Sect. 16.1 we address key features of DBR and differences from other research approaches. We also describe the meaning of validity and reliability in DBR and discuss how they can be improved. Section 16.2 illustrates DBR with an example from statistics education.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Less Can Be More: Encouraging Mastery of Research Design in Undergraduate Research Methods

Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches / sixth edition

Reflection on Design-Based Research: Challenges and Future Direction

Akkerman, S. F., Admiraal, W., Brekelmans, M., & Oost, H. (2008). Auditing quality of research in social sciences. Quality & Quantity, 42 , 257–274.

Article Google Scholar

Anderson, T., & Shattuck, J. (2012). Design-based research: A decade of progress in education research? Educational Researcher, 41 , 16–25.

Artigue, M. (1988). Ingénierie didactique [Didactical engineering]. In M. Artigue, G. Brousseau, J. Brun, Y. Chevallard, F. Conne, & G. Vergnaud (Eds.), Didactique des mathematiques [Didactics of mathematics]. Paris: Delachaux et Niestlé.

Google Scholar

Bakkenes, I., Vermunt, J. D., & Wubbels, T. (2010). Teachers learning in the context of educational innovation: Learning activities and learning outcomes of experienced teachers. Learning and Instruction, 20 (6), 533–548.

Bakker, A. (2004a). Design research in statistics education: On symbolizing and computer tools . Utrecht: CD-Bèta Press.

Bakker, A. (2004b). Reasoning about shape as a pattern in variability. Statistics Education Research Journal, 3 (2), 64–83. Online http://www.stat.auckland.ac.nz/~iase/serj/SERJ3(2)_Bakker.pdf

Bakker, A. (2007). Diagrammatic reasoning and hypostatic abstraction in statistics education. Semiotica, 164 , 9–29.

Bakker, A., & Derry, J. (2011). Lessons from inferentialism for statistics education. Mathematical Thinking and Learning, 13 , 5–26.

Bakker, A., & Gravemeijer, K. P. E. (2004). Learning to reason about distribution. In D. Ben-Zvi & J. Garfield (Eds.), The challenge of developing statistical literacy, reasoning, and thinking (pp. 147–168). Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Chapter Google Scholar

Bakker, A., & Gravemeijer, K. P. E. (2006). An historical phenomenology of mean and median. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 62 (2), 149–168.

Bakker, A., & Hoffmann, M. (2005). Diagrammatic reasoning as the basis for developing concepts: A semiotic analysis of students’ learning about statistical distribution. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 60 , 333–358.

Ben-Zvi, D., Aridor, K., Makar, K., & Bakker, A. (2012). Students’ emergent articulations of uncertainty while making informal statistical inferences. ZDM The International Journal on Mathematics Education, 44 , 913–925.

Biehler, R., Ben-Zvi, D., Bakker, A., & Makar, K. (2013). Technology for enhancing statistical reasoning at the school level. In M. A. Clement, A. J. Bishop, C. Keitel, J. Kilpatrick, & A. Y. L. Leung (Eds.), Third international handbook on mathematics education (pp. 643–689). New York: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-4684-2_21 .

Brown, A. (1992). Design experiments: Theoretical and methodological challenges in creating complex interventions in classroom settings. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 2 , 141–178.

Cicchetti, D. V. (1976). Assessing inter-rater reliability for rating scales: Resolving some basic issues. British Journal of Psychiatry, 129 , 452–456.

Cobb, P., & Whitenack, J. W. (1996). A method for conducting longitudinal analyses of classroom videorecordings and transcripts. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 30 (3), 213–228.

Cobb, P., Yackel, E., & Wood, T. (1992). A constructivist alternative to the representational view of mind in mathematics education. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 23 , 2–33.1.

Cobb, P., Gravemeijer, K.P.E., Bowers, J., & McClain, K. (1997). Statistical Minitools . Designed for Vanderbilt University, TN, USA. Programmed and revised (2001) at the Freudenthal Institute, Utrecht University, the Netherlands.

Cobb, P., Confrey, J., diSessa, A., Lehrer, R., & Schauble, L. (2003a). Design experiments in educational research. Educational Researcher, 32 (1), 9–13.

Cobb, P., McClain, K., & Gravemeijer, K. P. E. (2003b). Learning about statistical covariation. Cognition and Instruction, 21 , 1–78.

Collins, A. (1992). Toward a design science of education. In E. Scanlon & T. O'Shea (Eds.), New directions in educational technology (pp. 15–22). New York: Springer.

Cook, T. (2002). Randomized experiments in education: A critical examination of the reasons the educational evaluation community has offered for not doing them. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 24 (3), 175–199.

Creswell, J. W. (2005). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River: Pearson Education.

Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry and research design. Choosing among five traditions (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

De Jong, R., & Wijers, M. (1993). Ontwikkelingsonderzoek: Theorie en praktijk [Developmental research: Theory and practice]. Utrecht: NVORWO.

Denscombe, M. (2007). The good research guide (3rd ed.). Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Dierdorp, A., Bakker, A., Eijkelhof, H. M. C., & Van Maanen, J. A. (2011). Authentic practices as contexts for learning to draw inferences beyond correlated data. Mathematical Thinking and Learning, 13 , 132–151.

diSessa, A. A., & Cobb, P. (2004). Ontological innovation and the role of theory in design experiments. Educational Researcher, 32 (1), 77–103.

Drijvers, P. H. M. (2003). Learning algebra in a computer algebra environment: Design research on the understanding of the concept of parameter . Utrecht: CD-Beta Press.

Edelson, D. C. (2002). Design research: What we learn when we engage in design. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 11 , 105–121.

Educational Researcher. (2003). Special issue on design-based research collective, 32 (1–2).

Educational Psychologist. (2004). Special issue design-based research methods for studying learning in context, 39 (4).

Engeström, Y. (2011). From design experiments to formative interventions. Theory and Psychology, 21 (5), 598–628.

Fosnot, C. T., & Dolk, M. (2001). Young mathematicians at work. Constructing number sense, addition, and subtraction . Portsmouth: Heinemann.

Freudenthal, H. (1978). Weeding and sowing: Preface to a science of mathematical education . Dordrecht: Reidel.

Freudenthal, H. (1988). Ontwikkelingsonderzoek [Developmental research]. In K. Gravemeijer & K. Koster (Eds.), Onderzoek, ontwikkeling en ontwikkelingsonderzoek [Research, development and developmental research] . Universiteit Utrecht, the Netherlands: OW&OC.

Freudenthal, H. (1991). Revisiting mathematics education: China lectures . Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Frick, R. W. (1998). Interpreting statistical testing: Process and propensity, not population and random sampling. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 30 (3), 527–535.

Friel, S. N., Curcio, F. R., & Bright, G. W. (2001). Making sense of graphs: Critical factors influencing comprehension and instructional implications. Journal of Research in Mathematics Education., 32 (2), 124–158.

Geertz, C. (1973). Thick description: Toward an interpretive theory of culture. In C. Geertz (Ed.), The interpretation of cultures: Selected essays (pp. 3–30). New York: Basic Books.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research . Chicago: Aldine.

Goffree, F. (1979). Leren onderwijzen met Wiskobas. Onderwijsontwikkelingsonderzoek ‘Wiskunde en Didaktiek’ op de pedagogische akademie [Learning to teach Wiskobas. Educational development research]. Rijksuniversiteit Utrecht, The Netherlands.

Gravemeijer, K. P. E. (1994). Educational development and developmental research in mathematics education. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 25 (5), 443–471.

Gravemeijer, K. P. E., & Cobb, P. (2006). Design research from a learning design perspective. In J. Van den Akker, K. P. E. Gravemeijer, S. McKenney, & N. Nieveen (Eds.), Educational design research (pp. 17–51). London: Routledge.

Gravemeijer, K. P. E., & Koster, K. (Eds.). (1988). Onderzoek, ontwikkeling en ontwikkelingsonderzoek [Research, development, and developmental research]. Utrecht: OW&OC.

Guba, E. G. (1981). Criteria for assessing trustworthiness of naturalistic inquiries. Educational Communication and Technology Journal, 29 (2), 75–91.

Hoffmann, M. H. G. (2002). Peirce’s “diagrammatic reasoning” as a solution of the learning paradox. In G. Debrock (Ed.), Process pragmatism: Essays on a quiet philosophical revolution (pp. 147–174). Amsterdam: Rodopi Press.

Hoyles, C., Noss, R., Kent, P., & Bakker, A. (2010). Improving mathematics at work: The need for techno-mathematical literacies . Abingdon: Routledge.

Journal of the Learning Sciences (2004). Special issue on design-based research, 13(1), guest-edited by S. Barab and K. Squire.

Kanselaar, G. (1993). Ontwikkelingsonderzoek bezien vanuit de rol van de advocaat van de duivel [Design research: Taking the position of the devil’s advocate]. In R. de Jong & M. Wijers (Red.) (Eds.), Ontwikkelingsonderzoek, theorie en praktijk . Utrecht: NVORWO.

Konold, C., & Higgins, T. L. (2003). Reasoning about data. In J. Kilpatrick, W. G. Martin, & D. Schifter (Eds.), A research companion to principles and standards for school mathematics (pp. 193–215). Reston: National Council of Teachers of Mathematics.

Mathematical Thinking and Learning (2004). Special issue on learning trajectories in mathematics education , guest-edited by D. H. Clements and J. Sarama, 6(2).

Lehrer, R., & Schauble, L. (2001). Accounting for contingency in design experiments. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Education Research Association, Seattle.

Lewin, K. (1951). Problems of research in social psychology. In D. Cartwright (Ed.), Field theory in social science; selected theoretical papers . New York: Harper & Row.

Lijnse, P. L. (1995). “Developmental Research” as a way to an empirically based “didactical structure” of science. Science Education, 29 (2), 189–199.

Lijnse, P. L., & Klaassen, K. (2004). Didactical structures as an outcome of research on teaching-learning sequences? International Journal of Science Education, 26 (5), 537–554.

Maso, I., & Smaling, A. (1998). Kwalitatief onderzoek: praktijk en theorie [Qualitative research: Practice and theory]. Amsterdam: Boom.

Maxwell, J. A. (2004). Causal explanation, qualitative research and scientific inquiry in education. Educational Researcher, 33 (2), 3–11.

McClain, K., & Cobb, P. (2001). Supporting students’ ability to reason about data. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 45 , 103–129.

McKenney, S., & Reeves, T. (2012). Conducting educational design research . London: Routledge.

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: A sourcebook of new methods . Beverly Hills: Sage.

Nathan, M. J., & Kim, S. (2009). Regulation of teacher elicitations in the mathematics classroom. Cognition and Instruction, 27 (2), 91–120.

Olsen, D. R. (2004). The triumph of hope over experience in the search for “what works”: A response to Slavin. Educational Researcher, 33 (1), 24–26.

Oost, H., & Markenhof, A. (2010). Een onderzoek voorbereiden [Preparing research]. Amersfoort: Thieme Meulenhoff.

Opie, C. (2004). Doing educational research . London: Sage.

Paas, F. (2005). Design experiments: Neither a design nor an experiment. In C. P. Constantinou, D. Demetriou, A. Evagorou, M. Evagorou, A. Kofteros, M. Michael, C. Nicolaou, D. Papademetriou, & N. Papadouris (Eds.), Integrating multiple perspectives on effective learning environments. Proceedings of 11th biennial meeting of the European Association for Research on Learning and Instruction (pp. 901–902). Nicosia: University of Cyprus.

Peirce, C. S. (1976). The new elements of mathematics (C. Eisele, Ed.). The Hague: Mouton.

Peirce, C. S. (CP). Collected papers of Charles Sanders Peirce 1931–1958. In C. Hartshorne & P. Weiss (Eds.), Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Plomp, T. (2007). Educational design research: An introduction. In N. Nieveen & T. Plomp (Eds.), An introduction to educational design research (pp. 9–35). Enschede: SLO.

Plomp, T., & Nieveen, N. (Eds.). (2007). An introduction to educational design research . Enschede: SLO.

Romberg, T. A. (1973). Development research. Overview of how development-based research works in practice. Wisconsin Research and Development Center for Cognitive Learning, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison.

Sandoval, W. A., & Bell, P. (2004). Design-dased research methods for studying learning in context: Introduction. Educational Psychologist, 39 (4), 199–201.

Sfard, A., & Linchevski, L. (1992). The gains and the pitfalls of reification — The case of algebra. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 26 (2–3), 191–228.

Simon, M. (1995). Reconstructing mathematics pedagogy from a constructivistic perspective. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 26 (2), 114–145.

Slavin, R. E. (2002). Evidence-based educational policies: Transforming educational practice and research. Educational Researcher, 31 , 15–21.

Smit, J., & Van Eerde, H. A. A. (2011). A teacher’s learning process in dual design research: Learning to scaffold language in a multilingual mathematics classroom. ZDM The International Journal on Mathematics Education, 43 (6–7), 889–900.

Smit, J., van Eerde, H. A. A., & Bakker, A. (2013). A conceptualisation of whole-class scaffolding. British Educational Research Journal, 39 (5), 817–834.

Steffe, L. P., & Thompson, P. W. (2000). Teaching experiments methodology: Underlying principles and essential elements. In R. Lesh & A. E. Kelly (Eds.), Research design in mathematics and science education (pp. 267–307). Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (2nd ed.). London: Sage.

Tall, D., Thomas, M., Davis, G., Gray, E., & Simpson, A. (2000). What is the object of the encapsulation of a process? Journal of Mathematical Behavior, 18 , 223–241.

Treffers, A. (1987). Three dimensions. A model of goal and theory description in mathematics instruction. The Wiskobas project . Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Van den Akker, J. (1999). Principles and methods of development research. In J. van den Akker, R. M. Branch, K. Gustafson, N. Nieveen, & T. Plomp (Eds.), Design approaches and tools in education and training (pp. 1–14). Boston: Kluwer.

Van den Akker, J., Gravemeijer, K., McKenney, S., & Nieveen, N. (Eds.). (2006). Educational design research . London: Routledge.

Van den Heuvel-Panhuizen, M. (1996). Assessment and realistic mathematics education . Utrecht: CD-Bèta Press.

Van Nes, F., & Doorman, L. M. (2010). The interaction between multimedia data analysis and theory development in design research. Mathematics Education Research Journal, 22 (1), 6–30.

Wittmann, E. C. (1992). Didaktik der Mathematik als Ingenieurwissenschaft. [Didactics of mathematics as an engineering science.]. Zentralblatt für Didaktik der Mathematik, 3 , 119–121.

Yin, R. K. (2009). Case study research: Design and methods . Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Download references

Acknowledgments

The research was funded by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research under grant number 575-36-003B. The writing of this chapter was made possible with a grant from the Educational and Learning Sciences Utrecht awarded to Arthur Bakker. Section 2.6 is based on Bakker (2004b). We thank our Master students in our Research Methodology courses for their feedback on earlier versions of this manuscript. Angelika Bikner-Ahsbahs’s and reviewers’ careful reading has also helped us tremendously. We also acknowledge PhD students Adri Dierdorp, Al Jupri, and Victor Antwi, and our colleague Frans van Galen for their helpful comments, and Nathalie Kuijpers and Norma Presmeg for correcting this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Freudenthal Institute for Science and Mathematics Education, Utrecht University, Princetonplein 5, 3584 CC, Utrecht, The Netherlands

Arthur Bakker & Dolly van Eerde

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Arthur Bakker .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Faculty 3 of Mathematics and Computer Science, University of Bremen, Bremen, Germany

Angelika Bikner-Ahsbahs

Christine Knipping

Mathematics Department, Illinois State University, Normal, Illinois, USA

Norma Presmeg

Appendix: Structure of a DBR Project with Illustrations

In line with Oost and Markenhof ( 2010 ), we formulate the following general criteria for any research project:

The research should be anchored in the literature.

The research aim should be relevant , both in theoretical and practical terms.

The formulation of aim and questions should be precise , i.e. using concepts and definitions in the correct way.

The method used should be functional in answering the research question(s).

The overall structure of the research project should be consistent , i.e. title, aim, theory, question, method and results should form a coherent chain of reasoning.

In this appendix we present a structure of general points of attention during DBR and specifications for our statistics education example, including references to relevant sections in the chapter. In this structure these criteria are bolded. This structure could function as the blueprint of a book or article on a DBR project.

General points | Examples | |

|---|---|---|

Introduction: | 1. Choose a topic | 1. Statistics education at the middle school level |

2. Identify common problems | 2. Statistics as a set of unrelated concepts and techniques | |

3. Identify knowledge gap and relevance | 3. How middle school students can be supported to develop a concept of distribution and related statistical concepts | |

4. Choose mathematical learning goals | 4. Understanding of distribution (2.1) | |

Literature review forms the basis for formulating the research aim (the research has to be and ) | ||

Research aim: | It has to be clear whether an aim is descriptive, explanatory, evaluative, advisory etc. (1.2.2) | Contribute to an empirically and theoretically grounded instruction theory for statistics education at the middle school level (advisory aim) (2.1) |

Research aim has to be narrowed down to a research question and possibly subquestions with the help of different theories | ||

Literature review (theoretical background): | Orienting frameworks | Semiotics (2.3) |

Frameworks for action | Theories on learning with computer tools | |

Domain-specific learning theories (1.2.8) | Realistic Mathematics Education (2.4) | |

With the help of theoretical constructs the research question(s) can be formulated (the formulation has to be ) | ||

Research question: | Zoom in what knowledge is required to achieve the research aim | How can students with little statistical background develop a notion of distribution? |

It should be underpinned why this research question requires DBR (the method should be ) | ||

Research approach: | The lack of the type of learning aimed for is a common reason to carry out DBR: It has to be enacted so it can be studied | Dutch statistics education was atomistic: Textbooks addressed mean, median, mode, and different graphical representations one by one. Software was hardly used. Hence the type of learning aimed for had to be enacted. |

Using a research method involves several research instruments and techniques | ||

Research instruments and techniques | Research instrument that connects different theories and concrete experiences in the form of testable hypotheses. | Series of hypothetical learning trajectories (HLTs) |

1. Identify students’ prior knowledge | 1. Prior interviews and pretest | |

2. Professional development of teacher | 2. Preparatory meetings with teacher | |

3. Interview schemes and planning | 3. Mini-interviews, observation scheme | |

4. Intermediate feedback and reflection with teacher | 4. Debrief sessions with teacher | |

5. Determine learning yield (1.4.2) | 5. Posttest | |

Design | Design guidelines | Guided reinvention; Historical and didactical phenomenology (2.4) |

Data analysis | Hypotheses have to be tested by comparison of hypothetical and observed learning. Additional analyses may be necessary (1.4.3) | Comparison of hypothetical and observed learning |

Constant comparative method of generating conjectures and testing them on the remaining data sources (2.6) | ||

Results | Insights into patterns in learning and means of supporting such learning | Series of HLTs as progressive diagrammatic reasoning about growing samples (2.6) |

Discussion | Theoretical and practical yield | Concrete example of an historical and didactical phenomenology in statistics education |

Application of semiotics in an educational domain | ||

Insights into computer use in the mathematics classroom | ||

Series of learning activities | ||

Improved computer tools | ||

The aim, theory, question, method and results should be aligned (the research has to be ) | ||

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht

About this chapter

Bakker, A., van Eerde, D. (2015). An Introduction to Design-Based Research with an Example From Statistics Education. In: Bikner-Ahsbahs, A., Knipping, C., Presmeg, N. (eds) Approaches to Qualitative Research in Mathematics Education. Advances in Mathematics Education. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9181-6_16

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9181-6_16

Published : 05 September 2014

Publisher Name : Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN : 978-94-017-9180-9

Online ISBN : 978-94-017-9181-6

eBook Packages : Humanities, Social Sciences and Law Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Corpus ID: 1389686

Design-based research and doctoral students: Guidelines for preparing a dissertation proposal

- J. Herrington , S. McKenney , +1 author R. Oliver

- Published 25 June 2007

236 Citations

Design based research in doctoral studies: adding a new dimension to doctoral research.

- Highly Influenced

- 14 Excerpts

Using a design based research approach to explore the ways that primary school teachers conceptualise authentic learning: A work in progress

Adapting design-based research as a research methodology in educational settings, reflecting on challenges of conducting design-based research in large university courses, educational design research, designing mind map for a good research proposal for phd student in the uk : guidelines and reviewing, adopting design-based research to conduct a doctoral study as a micro-cycle of design – a practice illustration, is design-based research desirable and feasible methodology for educational media and technology , 21st century teacher skills: design principles for student engagement and success, design-based research (dbr) in educational enquiry and technological studies: a version for phd students targeting the integration of new technologies and literacies into educational contexts., 26 references, design-based research: an emerging paradigm for educational inquiry, the role of design in research: the integrative learning design framework, educational research: competencies for analysis and application, design research: a socially responsible approach to instructional technology research in higher education, design experiments in educational research, the effects of a web-based learning environment on student motivation in a high school earth science course, a development research agenda for online collaborative learning, principles and methods of development research.

- Highly Influential

Design-Based Research: Putting a Stake in the Ground

Computer-based support for science education materials developers in africa : exploring potentials, related papers.

Showing 1 through 3 of 0 Related Papers

- Section 2: Home

- Developing the Quantitative Research Design

- Qualitative Descriptive Design

- Design and Development Research (DDR) For Instructional Design

- Qualitative Narrative Inquiry Research

- Action Research Resource

- Case Study Design in an Applied Doctorate

Qualitative Research Designs

Case study design, using case study design in the applied doctoral experience (ade), applicability of case study design to applied problem of practice, case study design references.

- SAGE Research Methods

- Research Examples (SAGE) This link opens in a new window

- Dataset Examples (SAGE) This link opens in a new window

- IRB Resource Center This link opens in a new window

The field of qualitative research there are a number of research designs (also referred to as “traditions” or “genres”), including case study, phenomenology, narrative inquiry, action research, ethnography, grounded theory, as well as a number of critical genres including Feminist theory, indigenous research, critical race theory and cultural studies. The choice of research design is directly tied to and must be aligned with your research problem and purpose. As Bloomberg & Volpe (2019) explain:

Choice of research design is directly tied to research problem and purpose. As the researcher, you actively create the link among problem, purpose, and design through a process of reflecting on problem and purpose, focusing on researchable questions, and considering how to best address these questions. Thinking along these lines affords a research study methodological congruence (p. 38).

Case study is an in-depth exploration from multiple perspectives of a bounded social phenomenon, be this a social system such as a program, event, institution, organization, or community (Stake, 1995, 2005; Yin, 2018). Case study is employed across disciplines, including education, health care, social work, sociology, and organizational studies. The purpose is to generate understanding and deep insights to inform professional practice, policy development, and community or social action (Bloomberg 2018).

Yin (2018) and Stake (1995, 2005), two of the key proponents of case study methodology, use different terms to describe case studies. Yin categorizes case studies as exploratory or descriptive . The former is used to explore those situations in which the intervention being evaluated has no clear single set of outcomes. The latter is used to describe an intervention or phenomenon and the real-life context in which it occurred. Stake identifies case studies as intrinsic or instrumental , and he proposes that a primary distinction in designing case studies is between single and multiple (or collective) case study designs. A single case study may be an instrumental case study (research focuses on an issue or concern in one bounded case) or an intrinsic case study (the focus is on the case itself because the case presents a unique situation). A longitudinal case study design is chosen when the researcher seeks to examine the same single case at two or more different points in time or to capture trends over time. A multiple case study design is used when a researcher seeks to determine the prevalence or frequency of a particular phenomenon. This approach is useful when cases are used for purposes of a cross-case analysis in order to compare, contrast, and synthesize perspectives regarding the same issue. The focus is on the analysis of diverse cases to determine how these confirm the findings within or between cases, or call the findings into question.

Case study affords significant interaction with research participants, providing an in-depth picture of the phenomenon (Bloomberg & Volpe, 2019). Research is extensive, drawing on multiple methods of data collection, and involves multiple data sources. Triangulation is critical in attempting to obtain an in-depth understanding of the phenomenon under study and adds rigor, breadth, and depth to the study and provides corroborative evidence of the data obtained. Analysis of data can be holistic or embedded—that is, dealing with the whole or parts of the case (Yin, 2018). With multiple cases the typical analytic strategy is to provide detailed description of themes within each case (within-case analysis), followed by thematic analysis across cases (cross-case analysis), providing insights regarding how individual cases are comparable along important dimensions. Research culminates in the production of a detailed description of a setting and its participants, accompanied by an analysis of the data for themes or patterns (Stake, 1995, 2005; Yin, 2018). In addition to thick, rich description, the researcher’s interpretations, conclusions, and recommendations contribute to the reader’s overall understanding of the case study.

Analysis of findings should show that the researcher has attended to all the data, should address the most significant aspects of the case, and should demonstrate familiarity with the prevailing thinking and discourse about the topic. The goal of case study design (as with all qualitative designs) is not generalizability but rather transferability —that is, how (if at all) and in what ways understanding and knowledge can be applied in similar contexts and settings. The qualitative researcher attempts to address the issue of transferability by way of thick, rich description that will provide the basis for a case or cases to have relevance and potential application across a broader context.

Qualitative research methods ask the questions of "what" and "how" a phenomenon is understood in a real-life context (Bloomberg & Volpe, 2019). In the education field, qualitative research methods uncover educational experiences and practices because qualitative research allows the researcher to reveal new knowledge and understanding. Moreover, qualitative descriptive case studies describe, analyze and interpret events that explain the reasoning behind specific phenomena (Bloomberg, 2018). As such, case study design can be the foundation for a rigorous study within the Applied Doctoral Experience (ADE).

Case study design is an appropriate research design to consider when conceptualizing and conducting a dissertation research study that is based on an applied problem of practice with inherent real-life educational implications. Case study researchers study current, real-life cases that are in progress so that they can gather accurate information that is current. This fits well with the ADE program, as students are typically exploring a problem of practice. Because of the flexibility of the methods used, a descriptive design provides the researcher with the opportunity to choose data collection methods that are best suited to a practice-based research purpose, and can include individual interviews, focus groups, observation, surveys, and critical incident questionnaires. Methods are triangulated to contribute to the study’s trustworthiness. In selecting the set of data collection methods, it is important that the researcher carefully consider the alignment between research questions and the type of data that is needed to address these. Each data source is one piece of the “puzzle,” that contributes to the researcher’s holistic understanding of a phenomenon. The various strands of data are woven together holistically to promote a deeper understanding of the case and its application to an educationally-based problem of practice.

Research studies within the Applied Doctoral Experience (ADE) will be practical in nature and focus on problems and issues that inform educational practice. Many of the types of studies that fall within the ADE framework are exploratory, and align with case study design. Case study design fits very well with applied problems related to educational practice, as the following set of examples illustrate:

Elementary Bilingual Education Teachers’ Self-Efficacy in Teaching English Language Learners: A Qualitative Case Study

The problem to be addressed in the proposed study is that some elementary bilingual education teachers’ beliefs about their lack of preparedness to teach the English language may negatively impact the language proficiency skills of Hispanic ELLs (Ernst-Slavit & Wenger, 2016; Fuchs et al., 2018; Hoque, 2016). The purpose of the proposed qualitative descriptive case study was to explore the perspectives and experiences of elementary bilingual education teachers regarding their perceived lack of preparedness to teach the English language and how this may impact the language proficiency of Hispanic ELLs.

Exploring Minority Teachers Experiences Pertaining to their Value in Education: A Single Case Study of Teachers in New York City

The problem is that minority K-12 teachers are underrepresented in the United States, with research indicating that school leaders and teachers in schools that are populated mainly by black students, staffed mostly by white teachers who may be unprepared to deal with biases and stereotypes that are ingrained in schools (Egalite, Kisida, & Winters, 2015; Milligan & Howley, 2015). The purpose of this qualitative exploratory single case study was to develop a clearer understanding of minority teachers’ experiences concerning the under-representation of minority K-12 teachers in urban school districts in the United States since there are so few of them.

Exploring the Impact of an Urban Teacher Residency Program on Teachers’ Cultural Intelligence: A Qualitative Case Study

The problem to be addressed by this case study is that teacher candidates often report being unprepared and ill-equipped to effectively educate culturally diverse students (Skepple, 2015; Beutel, 2018). The purpose of this study was to explore and gain an in-depth understanding of the perceived impact of an urban teacher residency program in urban Iowa on teachers’ cultural competence using the cultural intelligence (CQ) framework (Earley & Ang, 2003).

Qualitative Case Study that Explores Self-Efficacy and Mentorship on Women in Academic Administrative Leadership Roles

The problem was that female school-level administrators might be less likely to experience mentorship, thereby potentially decreasing their self-efficacy (Bing & Smith, 2019; Brown, 2020; Grant, 2021). The purpose of this case study was to determine to what extent female school-level administrators in the United States who had a mentor have a sense of self-efficacy and to examine the relationship between mentorship and self-efficacy.

Suburban Teacher and Administrator Perceptions of Culturally Responsive Teaching to Promote Connectedness in Students of Color: A Qualitative Case Study

The problem to be addressed in this study is the racial discrimination experienced by students of color in suburban schools and the resulting negative school experience (Jara & Bloomsbury, 2020; Jones, 2019; Kohli et al., 2017; Wandix-White, 2020). The purpose of this case study is to explore how culturally responsive practices can counteract systemic racism and discrimination in suburban schools thereby meeting the needs of students of color by creating positive learning experiences.

As you can see, all of these studies were well suited to qualitative case study design. In each of these studies, the applied research problem and research purpose were clearly grounded in educational practice as well as directly aligned with qualitative case study methodology. In the Applied Doctoral Experience (ADE), you will be focused on addressing or resolving an educationally relevant research problem of practice. As such, your case study, with clear boundaries, will be one that centers on a real-life authentic problem in your field of practice that you believe is in need of resolution or improvement, and that the outcome thereof will be educationally valuable.

Bloomberg, L. D. (2018). Case study method. In B. B. Frey (Ed.), The SAGE Encyclopedia of educational research, measurement, and evaluation (pp. 237–239). SAGE. https://go.openathens.net/redirector/nu.edu?url=https%3A%2F%2Fmethods.sagepub.com%2FReference%2Fthe-sage-encyclopedia-of-educational-research-measurement-and-evaluation%2Fi4294.xml

Bloomberg, L. D. & Volpe, M. (2019). Completing your qualitative dissertation: A road map from beginning to end . (4th Ed.). SAGE.

Stake, R. E. (1995). The art of case study research. SAGE.

Stake, R. E. (2005). Qualitative case studies. In N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative research (3rd ed., pp. 443–466). SAGE.

Yin, R. (2018). Case study research and applications: Designs and methods. SAGE.

- << Previous: Action Research Resource

- Next: SAGE Research Methods >>

- Last Updated: Jul 28, 2023 8:05 AM

- URL: https://resources.nu.edu/c.php?g=1013605

© Copyright 2024 National University. All Rights Reserved.

Privacy Policy | Consumer Information

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Design-based research and doctoral students: Guidelines for preparing a dissertation proposal

2007, Proceedings of EdMedia

At first glance, design-based research may appear to be such a long-term and intensive approach to educational inquiry that doctoral students, most of whom expect to complete their Ph. D. degree in 4-5 years, should not attempt to adopt this approach for their doctoral dissertations. In this paper, we argue that design-based research is feasible for doctoral students, and that candidates should be encouraged to engage in it. More specifically, we describe the components of a dissertation proposal or prospectus that utilizes design- ...

Related Papers

International Journal of Doctoral Studies

Seyum Getenet

Aim/Purpose: We show a new dimension to the process of using design-based research approach in doctoral dissertations. Background: Design-based research is a long-term and concentrated approach to educational inquiry. It is often a recommendation that doctoral students should not attempt to adopt this approach for their doctoral dissertations. In this paper, we document two doctoral dissertations that used a design-based research approach in two different contexts. Methodology : The study draws on a qualitative analysis of the methodological approaches of two doctoral dissertations through the lenses of Herrington, McKenney, Reeves and Oliver principles of design-based research approach. Contribution: The findings of this study add a new dimension to using design-based research approach in doctoral dissertations in shorter-term and less intensive contexts. Findings: The results of this study indicate that design-based research is not only an effective methodological approach in doct...

Educational Researcher

Christopher Hoadley

Jennifer K . Shah

The science-to-service problem continues to taunt the field of education (Fixsen, Blasé, Naoom, & Wallace, 2009). As an academic discipline, the field requires knowledge generation that adds to or deepens theoretical understandings. As a profession, knowledge generation that solves local problems and supports continuous improvement is necessary. Using design-based research (DBR) provides a means of serving theoretical and practical needs in education, addressing the complexity of education by informing immediate practice while simultaneously contributing to theoretical understandings in the field of education. Using Stokes' (1977) model of scientific research and knowledge generation, we situate DBR within Pasteur's quadrant, describe how to increase its use, and recommend a new means for dissemination. The debate over the theory-to-practice divide continues in many fields, including education. Coburn and Stein (2010) suggested that the path from theoretical knowledge to classroom application is neither linear nor direct. Fixsen et al. (2009) stated that research results are not utilized enough to impact communities. In essence, the current process of scholars disseminating information and practitioners applying information results in a perpetual science-to-service problem. Given the complexity that lies at the heart of teaching and learning (Cochran-Smith, 2003), it is no longer reasonable to rely on the passive dissemination of knowledge. Rather, researchers and practitioners must collaborate to create and disseminate knowledge that will address the issues facing education today. This will require not only generating knowledge to expand understandings of theoretical foundations that comprise the science of the field, but also generating knowledge from practice that elucidates the act of applying the science of education. The purpose of the this article is to discuss the role that design-based research (DBR) can play in addressing the complexity of education, by informing immediate practice while simultaneously continuing to develop theoretical understandings in the field of education. In this article the authors: 1) describe Stokes' (1977) quadrant model of scientific research and elaborate on DBR's placement in Pasteur's quadrant based on its dual purpose of theoretical knowledge generation and practical knowledge generation; 2) describe the foundational elements of DBR; 3) discuss ideas of how to increase DBR use in education research; and 4) suggest an approach to disseminating DBR research that more accurately represents the methodological practice of this type of research. Overcoming the Theory to Practice Divide: Dwelling in Pasteur's Quadrant The process of knowledge dissemination suggests that knowledge generated to broaden the theoretical understandings in a discipline will directly lead to the application of that knowledge

Educational Psychologist

Philip Bell

The Design Journal

Violeta Clemente , Katja Tschimmel

Within the fruitful discussion about what design research should mean and achieve and the implication for doctoral education, this paper aims to explore the topic regarding the boundaries between project design research and academic design research. There is also a strong movement within the academic milieu in the realm of design, namely within international conferences and research meetings, to discuss methodologies and processes as a paramount contribution to defining scientific research in design. PhD design research in Portuguese universities started slowly in the late 1990s, but is increasingly establishing itself as a worthy degree. This text focuses on an original study depicting the state of the art of the methodological approaches applied in doctoral design research in Portugal. It proposes a Design Research Classification Model and a Design Research Canvas that can be applied to other systematic reviews of design research as a means of synthesising the past to outline the future. It is also a major objective of this work to contribute to a clarification of a methodological framework, which relates practice-based research to academic research.

Fatina Saikaly

Different philosophical assumptions, aims, structures, contents and processes underlie the Ph.D. programmes in design offered in different socio-cultural contexts. In order to get a deep understanding of the actual state of doctoral research in design, a comparative study of ten selected programmes was developed. The study covered universities from the North of America, Europe, Asia and Australia. Each case study was divided in three parts. A first part was related to the study of the doctoral programme. The second part was the study of selected Ph.D. theses. And finally an interview took place with one of the programme advisors. In this paper I will present the results of the comparative study. The points to be discussed are: (i) The different philosophical assumptions that guide doctoral programmes in design; How these different philosophical assumptions led to different learning experiences and contributed to the development of different skills and competencies; (ii) The different positions and roles of the design project in different research settings. I will conclude the paper by introducing two points that deserve further exploration. The first one is related to the practice-centred Ph.D. programmes in design. The other one concerns the reasons why the role of the design project in doctoral research is evolving and gaining more status.

Diana Joseph

Educational …

Michael J Feuer

The authors argue that design studies, like all scientific work, must comport with guiding scientific principles and provide adequate war-rants for their knowledge claims. The issue is whether their knowl-edge claims can be warranted. By their very nature, design studies are ...

WJET Journal

Maribel González Allende

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

Comparison. Conference for Artistic and Architectural Research. Book of Proceedings. Edited by Fabrizia Berlingieri, Francesca Zanotto with the contribution of Beatrice Balducci, Jacopo Leveratto, Claudia Mainardi, Enrico Miglietta, Chiara Pradel, Pier Paolo Tamburelli. LetteraVentidue, Siracusa

Chiara Pradel

STRATEGIES OF DESIGN-DRIVEN RESEARCH

Alessandro Rocca

Journal of the Association for Information Systems

Mark Toleman

Journal of the Learning Sciences

kurt squire

Wouter Eggink

World Journal on Educational Technology

Tina Štemberger

The Journal of Public Space

Mick Abbott

Ken Friedman

Peter Vistisen

Online Learning

Darragh McNally

Design Research Society International Conference, K. …

Wolfgang Jonas

Educational Design Research (EDeR)

Louis Major

Mithra Zahedi , Danny Godin

Medical Education

Susan McKenney

William Gaver

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Design-based research and doctoral students: Guidelines for preparing a dissertation proposal

- Faculty of Behavioural, Management and Social Sciences

- Educational Science

Research output : Chapter in Book/Report/Conference proceeding › Conference contribution › Academic › peer-review

| Original language | English |

|---|---|

| Title of host publication | Proceedings of World Conference on Educational Multimedia, Hypermedia and Telecommunications 2007 |

| Editors | C. Montgomerie, J. Seale |

| Pages | 4089-4097 |

| Number of pages | 10 |

| Publication status | Published - 25 Jun 2007 |

| Event | - Vancouver, Canada Duration: 25 Jun 2007 → 27 Jun 2007 |

| Conference | World Conference on Educational Multimedia, Hypermedia & Telecommunications 2007 |

|---|---|

| Abbreviated title | ED-MEDIA 2007 |

| Country/Territory | Canada |

| City | Vancouver |

| Period | 25/06/07 → 27/06/07 |

- METIS-243753

Access to Document

- Design-based research and doctoral students Final published version, 505 KB

- http://ro.ecu.edu.au/ecuworks/1612/

Fingerprint

- Theses Social Sciences 100%

- Design Social Sciences 100%

- Research Social Sciences 100%

- Students Social Sciences 100%

- Doctoral Student Computer Science 100%

- Practice Guideline Nursing and Health Professions 100%

- Student Nursing and Health Professions 100%

- Doctoral students Arts and Humanities 100%

T1 - Design-based research and doctoral students: Guidelines for preparing a dissertation proposal

AU - Herrington, Jan

AU - McKenney, Susan

AU - Reeves, Thomas C.

AU - Oliver, Ron

PY - 2007/6/25

Y1 - 2007/6/25

N2 - At first glance, design-based research may appear to be such a long-term and intensive approach to educational inquiry that doctoral students, most of whom expect to complete their Ph.D. degree in 4-5 years, should not attempt to adopt this approach for their doctoral dissertations. In this paper, we argue that design-based research is feasible for doctoral students, and that candidates should be encouraged to engage in it. More specifically, we describe the components of a dissertation proposal or prospectus that utilizes design-based research methods in the context of educational technology research.

AB - At first glance, design-based research may appear to be such a long-term and intensive approach to educational inquiry that doctoral students, most of whom expect to complete their Ph.D. degree in 4-5 years, should not attempt to adopt this approach for their doctoral dissertations. In this paper, we argue that design-based research is feasible for doctoral students, and that candidates should be encouraged to engage in it. More specifically, we describe the components of a dissertation proposal or prospectus that utilizes design-based research methods in the context of educational technology research.

KW - IR-93893

KW - METIS-243753

M3 - Conference contribution

BT - Proceedings of World Conference on Educational Multimedia, Hypermedia and Telecommunications 2007

A2 - Montgomerie, C.

A2 - Seale, J.

T2 - World Conference on Educational Multimedia, Hypermedia & Telecommunications 2007

Y2 - 25 June 2007 through 27 June 2007

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

Research Design | Step-by-Step Guide with Examples

Published on 5 May 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 20 March 2023.

A research design is a strategy for answering your research question using empirical data. Creating a research design means making decisions about:

- Your overall aims and approach

- The type of research design you’ll use

- Your sampling methods or criteria for selecting subjects

- Your data collection methods

- The procedures you’ll follow to collect data

- Your data analysis methods

A well-planned research design helps ensure that your methods match your research aims and that you use the right kind of analysis for your data.

Table of contents

Step 1: consider your aims and approach, step 2: choose a type of research design, step 3: identify your population and sampling method, step 4: choose your data collection methods, step 5: plan your data collection procedures, step 6: decide on your data analysis strategies, frequently asked questions.

- Introduction

Before you can start designing your research, you should already have a clear idea of the research question you want to investigate.

There are many different ways you could go about answering this question. Your research design choices should be driven by your aims and priorities – start by thinking carefully about what you want to achieve.

The first choice you need to make is whether you’ll take a qualitative or quantitative approach.

| Qualitative approach | Quantitative approach |

|---|---|

Qualitative research designs tend to be more flexible and inductive , allowing you to adjust your approach based on what you find throughout the research process.

Quantitative research designs tend to be more fixed and deductive , with variables and hypotheses clearly defined in advance of data collection.

It’s also possible to use a mixed methods design that integrates aspects of both approaches. By combining qualitative and quantitative insights, you can gain a more complete picture of the problem you’re studying and strengthen the credibility of your conclusions.

Practical and ethical considerations when designing research

As well as scientific considerations, you need to think practically when designing your research. If your research involves people or animals, you also need to consider research ethics .

- How much time do you have to collect data and write up the research?

- Will you be able to gain access to the data you need (e.g., by travelling to a specific location or contacting specific people)?

- Do you have the necessary research skills (e.g., statistical analysis or interview techniques)?

- Will you need ethical approval ?

At each stage of the research design process, make sure that your choices are practically feasible.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Within both qualitative and quantitative approaches, there are several types of research design to choose from. Each type provides a framework for the overall shape of your research.

Types of quantitative research designs

Quantitative designs can be split into four main types. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs allow you to test cause-and-effect relationships, while descriptive and correlational designs allow you to measure variables and describe relationships between them.

| Type of design | Purpose and characteristics |

|---|---|

| Experimental | |

| Quasi-experimental | |

| Correlational | |

| Descriptive |

With descriptive and correlational designs, you can get a clear picture of characteristics, trends, and relationships as they exist in the real world. However, you can’t draw conclusions about cause and effect (because correlation doesn’t imply causation ).

Experiments are the strongest way to test cause-and-effect relationships without the risk of other variables influencing the results. However, their controlled conditions may not always reflect how things work in the real world. They’re often also more difficult and expensive to implement.

Types of qualitative research designs

Qualitative designs are less strictly defined. This approach is about gaining a rich, detailed understanding of a specific context or phenomenon, and you can often be more creative and flexible in designing your research.

The table below shows some common types of qualitative design. They often have similar approaches in terms of data collection, but focus on different aspects when analysing the data.

| Type of design | Purpose and characteristics |

|---|---|

| Grounded theory | |

| Phenomenology |

Your research design should clearly define who or what your research will focus on, and how you’ll go about choosing your participants or subjects.

In research, a population is the entire group that you want to draw conclusions about, while a sample is the smaller group of individuals you’ll actually collect data from.

Defining the population

A population can be made up of anything you want to study – plants, animals, organisations, texts, countries, etc. In the social sciences, it most often refers to a group of people.

For example, will you focus on people from a specific demographic, region, or background? Are you interested in people with a certain job or medical condition, or users of a particular product?

The more precisely you define your population, the easier it will be to gather a representative sample.

Sampling methods

Even with a narrowly defined population, it’s rarely possible to collect data from every individual. Instead, you’ll collect data from a sample.

To select a sample, there are two main approaches: probability sampling and non-probability sampling . The sampling method you use affects how confidently you can generalise your results to the population as a whole.

| Probability sampling | Non-probability sampling |

|---|---|

Probability sampling is the most statistically valid option, but it’s often difficult to achieve unless you’re dealing with a very small and accessible population.

For practical reasons, many studies use non-probability sampling, but it’s important to be aware of the limitations and carefully consider potential biases. You should always make an effort to gather a sample that’s as representative as possible of the population.

Case selection in qualitative research

In some types of qualitative designs, sampling may not be relevant.

For example, in an ethnography or a case study, your aim is to deeply understand a specific context, not to generalise to a population. Instead of sampling, you may simply aim to collect as much data as possible about the context you are studying.

In these types of design, you still have to carefully consider your choice of case or community. You should have a clear rationale for why this particular case is suitable for answering your research question.

For example, you might choose a case study that reveals an unusual or neglected aspect of your research problem, or you might choose several very similar or very different cases in order to compare them.

Data collection methods are ways of directly measuring variables and gathering information. They allow you to gain first-hand knowledge and original insights into your research problem.

You can choose just one data collection method, or use several methods in the same study.

Survey methods

Surveys allow you to collect data about opinions, behaviours, experiences, and characteristics by asking people directly. There are two main survey methods to choose from: questionnaires and interviews.

| Questionnaires | Interviews |

|---|---|

Observation methods

Observations allow you to collect data unobtrusively, observing characteristics, behaviours, or social interactions without relying on self-reporting.

Observations may be conducted in real time, taking notes as you observe, or you might make audiovisual recordings for later analysis. They can be qualitative or quantitative.

| Quantitative observation | |

|---|---|

Other methods of data collection

There are many other ways you might collect data depending on your field and topic.

| Field | Examples of data collection methods |

|---|---|

| Media & communication | Collecting a sample of texts (e.g., speeches, articles, or social media posts) for data on cultural norms and narratives |

| Psychology | Using technologies like neuroimaging, eye-tracking, or computer-based tasks to collect data on things like attention, emotional response, or reaction time |

| Education | Using tests or assignments to collect data on knowledge and skills |

| Physical sciences | Using scientific instruments to collect data on things like weight, blood pressure, or chemical composition |

If you’re not sure which methods will work best for your research design, try reading some papers in your field to see what data collection methods they used.

Secondary data

If you don’t have the time or resources to collect data from the population you’re interested in, you can also choose to use secondary data that other researchers already collected – for example, datasets from government surveys or previous studies on your topic.

With this raw data, you can do your own analysis to answer new research questions that weren’t addressed by the original study.

Using secondary data can expand the scope of your research, as you may be able to access much larger and more varied samples than you could collect yourself.

However, it also means you don’t have any control over which variables to measure or how to measure them, so the conclusions you can draw may be limited.

As well as deciding on your methods, you need to plan exactly how you’ll use these methods to collect data that’s consistent, accurate, and unbiased.

Planning systematic procedures is especially important in quantitative research, where you need to precisely define your variables and ensure your measurements are reliable and valid.

Operationalisation

Some variables, like height or age, are easily measured. But often you’ll be dealing with more abstract concepts, like satisfaction, anxiety, or competence. Operationalisation means turning these fuzzy ideas into measurable indicators.

If you’re using observations , which events or actions will you count?

If you’re using surveys , which questions will you ask and what range of responses will be offered?

You may also choose to use or adapt existing materials designed to measure the concept you’re interested in – for example, questionnaires or inventories whose reliability and validity has already been established.

Reliability and validity

Reliability means your results can be consistently reproduced , while validity means that you’re actually measuring the concept you’re interested in.

| Reliability | Validity |

|---|---|

For valid and reliable results, your measurement materials should be thoroughly researched and carefully designed. Plan your procedures to make sure you carry out the same steps in the same way for each participant.

If you’re developing a new questionnaire or other instrument to measure a specific concept, running a pilot study allows you to check its validity and reliability in advance.

Sampling procedures

As well as choosing an appropriate sampling method, you need a concrete plan for how you’ll actually contact and recruit your selected sample.

That means making decisions about things like:

- How many participants do you need for an adequate sample size?

- What inclusion and exclusion criteria will you use to identify eligible participants?

- How will you contact your sample – by mail, online, by phone, or in person?

If you’re using a probability sampling method, it’s important that everyone who is randomly selected actually participates in the study. How will you ensure a high response rate?

If you’re using a non-probability method, how will you avoid bias and ensure a representative sample?

Data management

It’s also important to create a data management plan for organising and storing your data.

Will you need to transcribe interviews or perform data entry for observations? You should anonymise and safeguard any sensitive data, and make sure it’s backed up regularly.

Keeping your data well organised will save time when it comes to analysing them. It can also help other researchers validate and add to your findings.

On their own, raw data can’t answer your research question. The last step of designing your research is planning how you’ll analyse the data.

Quantitative data analysis

In quantitative research, you’ll most likely use some form of statistical analysis . With statistics, you can summarise your sample data, make estimates, and test hypotheses.

Using descriptive statistics , you can summarise your sample data in terms of:

- The distribution of the data (e.g., the frequency of each score on a test)

- The central tendency of the data (e.g., the mean to describe the average score)

- The variability of the data (e.g., the standard deviation to describe how spread out the scores are)

The specific calculations you can do depend on the level of measurement of your variables.

Using inferential statistics , you can:

- Make estimates about the population based on your sample data.

- Test hypotheses about a relationship between variables.

Regression and correlation tests look for associations between two or more variables, while comparison tests (such as t tests and ANOVAs ) look for differences in the outcomes of different groups.

Your choice of statistical test depends on various aspects of your research design, including the types of variables you’re dealing with and the distribution of your data.

Qualitative data analysis

In qualitative research, your data will usually be very dense with information and ideas. Instead of summing it up in numbers, you’ll need to comb through the data in detail, interpret its meanings, identify patterns, and extract the parts that are most relevant to your research question.

Two of the most common approaches to doing this are thematic analysis and discourse analysis .

| Approach | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Thematic analysis | |

| Discourse analysis |

There are many other ways of analysing qualitative data depending on the aims of your research. To get a sense of potential approaches, try reading some qualitative research papers in your field.